Abstract

There have been several studies on the antitumor activities of vitamin E succinate (α‐TOS) as complementary and alternative medicine. In the present study, we investigated the cytotoxic effect of α‐TOS and the enhancement of chemosensitivity to paclitaxel by α‐TOS in bladder cancer. KU‐19‐19 and 5637 bladder cancer cell lines were cultured in α‐TOS and/or paclitaxel in vitro. Cell viability, flow cytometric analysis, and nuclear factor‐kappa B (NF‐κB) activity were analyzed. For in vivo therapeutic experiments, pre‐established KU‐19‐19 tumors were treated with α‐TOS and/or paclitaxel. In KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells, the combination treatment resulted in a significantly higher level of growth inhibition, and apoptosis was significantly induced by the combination treatment. NF‐κB was activated by paclitaxel; however, the activation of NF‐κB was inhibited by α‐TOS. Also, the combination treatment significantly inhibited tumor growth in mice. In the immunostaining of the tumors, apoptosis was induced and proliferation was inhibited by the combination treatment. Combination treatment of α‐TOS and paclitaxel showed promising anticancer effects in terms of inhibiting bladder cancer cell growth and viability in vitro and in vivo. One of the potential mechanisms by which the combination therapy has synergistic cytotoxic effects against bladder cancer may be that α‐TOS inhibits NF‐κB induced by chemotherapeutic agents. (Cancer Sci 2009;)

The prognosis for patients with advanced or metastatic bladder cancer remains poor, with a median survival of approximately 12 months. Systemic chemotherapy is the only current modality that provides the potential for somewhat long‐term survival in patients with advanced or metastatic bladder cancer. Methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (M‐VAC) has been the most common treatment regimen for advanced or metastatic bladder cancer since the 1980s.( 1 ) The M‐VAC regimen has been reported to produce a complete response in approximately 20% of patients, although long‐term disease‐free survival is rare.( 2 ) M‐VAC, though superior to single agent therapy, is associated with significant toxicity (more than 20% of recipients experience neutropenic fever). These disappointing results have prompted a search for additional agents and multidrug combinations.

Taxoids are microtubule disassembly inhibitors and represent a new class of agents for use in cancer chemotherapy. Recently, the use of paclitaxel or docetaxel, a semisynthetic taxane, has been started in clinical trials in patients with advanced bladder cancer. Paclitaxel has demonstrated substantial single‐agent activity in the treatment of advanced or metastatic bladder cancer.( 3 , 4 ) Paclitaxel in combination with gemcitabine has shown promise for the treatment of patients with M‐VAC refractory bladder cancer.( 5 , 6 ) Paclitaxel causes cell death by inhibiting depolymerization of tubulin with resultant arrest in cell cycle progression, particularly at the G2/M interface.( 7 ) Besides this function, it also possesses cell‐killing activity through its induction of apoptosis.( 8 )

Vitamin E succinate (α‐TOS, RRR‐α‐tocopherol succinate), a derivative of vitamin E, is currently being characterized for its chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic potential.( 9 ) There have been several studies on the antitumor activities of α‐TOS as complementary and alternative medicine. Many groups have reported that α‐TOS can inhibit proliferation and trigger apoptosis of malignant cells in vitro and in vivo. Previous studies have shown that α‐TOS inhibits tumor cell growth by a variety of mechanisms, including DNA synthesis arrest,( 10 , 11 ) induction of apoptosis,( 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ) inhibition of tumor cell proliferation and differentiation,( 16 , 17 ) cell cycle blockade,( 18 , 19 ) inhibition of angiogenesis,( 20 , 21 ) suppression of nuclear factor‐kappa B (NF‐κB) activation,( 22 , 23 ) induced secretion and activation of transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β,( 24 , 25 ) enhanced expression of TGF‐β type II receptors,( 26 ) and enhanced cell surface expression of Fas (CD95)( 27 , 28 ) in various cancer cell lines. In addition, α‐TOS selectively kills tumor cells without any toxic effects on normal cells or tissues.( 12 , 13 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ) Still, there has been no report that evaluated the antitumor effect of α‐TOS in bladder cancers. Furthermore, the mechanisms of α‐TOS‐induced cancer cell apoptosis and inhibition of cancer cell growth are not fully understood.

In the present study, we investigated (1) the cytotoxic effect of α‐TOS in bladder cancer in vitro and in vivo; (2) whether α‐TOS pretreatment could enhance the therapeutic effect of paclitaxel; and (3) the detailed mechanism by which the combination treatment could have an antitumor effect synergistically in a bladder tumor model.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and chemicals. Two human bladder cancer cell lines, KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells, were used. KU‐19‐19 cells, an aggressive human bladder cancer cell line, were established in our laboratory,( 35 ) while 5637 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells were cultured at 37°C in RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Dainippon Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan), 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin in a water‐saturated atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2.

Vitamin E derivatives, such as α‐tocopherol (α‐TOH), α‐tocopherol acetate (α‐TOA), α‐tocopherol succinate (α‐TOS) (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO, USA), and γ‐tocotrienol (γ‐T3) (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), were purchased from a commercial vendor. Vitamin E derivatives were dissolved in ethanol to prepare a 20–80 mm solution and subsequently diluted in the cell culture medium to a final ethanol concentration of <0.1%. Paclitaxel was obtained from Bristol‐Myers Squibb (Tokyo, Japan).

Cell growth assay. KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells were seeded in 96‐well plates at a cell density of 1 × 104 cells resuspended in 100 μL per well and incubated at 37°C overnight. Then both cell types were treated with various concentrations of vitamin E derivatives and/or paclitaxel for 24–72 h.

For the α‐TOS and paclitaxel combination treatment, cells were pre‐incubated with α‐TOS for 3 h before addition of paclitaxel to each well and then incubating the plate for 48 h.

After the treatment, 10 μL of WST‐1 (4‐[3‐(4‐iodophenyl)‐2‐(4‐nitrophenyl)‐2H‐5‐tetrazolio]‐1,3‐benzene disulfonate) assay solution (Roche, Pendberg, Germany) was added into each well,and the cells were incubated at 37°C for 3 h and cell viability was determined. The absorbance value of each well was determined at 450 nm with a 655 nm reference beam in a microplate reader (Bio‐Rad, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell cycle and apoptosis assay. Flow cytometric analysis was performed using TUNEL assay for detecting apoptosis, and BrdU for cell cycle analysis. Briefly, cells (1 × 106) were plated in 100 mm dishes and allowed to attach overnight. They were then treated with various concentrations of α‐TOS and/or paclitaxel for different periods of time. And cells were harvested by trypsinisation, fixed in 70% ethanol at 4°C overnight, and then resuspended in PBS containing 0.05 mg/mL RNase A (Sigma Chemical), and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. After washing, the cells were stained with FITC‐labeled BrdU and propidium iodide and analyzed by flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). TUNEL assay was performed using ApopTag kits (Sigma Chemical), apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry, and subsequent analysis was carried out according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Determination of NF‐κB activity. Nuclear extracts were prepared using NE‐PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA). Nuclear extracts (15 μg of protein per well) were incubated in 96‐well plates coated with immobilized oligonucleotide, containing an NF‐κB consensus binding site. NF‐κB binding to target oligonucleotides was detected by incubation of samples with primary antibodies against the p65 subunit provided with the Trans‐AM NF‐κB p65 transcription factor assay kit (Active Motif North America, Carlsbad, CA, USA). For detection, optimal densities were measured at 450 nm with a microplate reader.

Western blot analysis. Samples (40 μg of protein) were mixed with loading buffer, resolved by 12.5% SDS‐PAGE, and transblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking with 5% dry skim milk, the membrane was then incubated with primary antibodies for overnight against IκBα, phospho‐IκBα, NF‐κB p65 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA), c‐IAP1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), β‐actin (Sigma Chemical) and Lamin A/C (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). After incubation with appropriate secondary antibodies, signals were visualized by ECL Western blotting system (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Treatment with NF‐κB p65 siRNA and paclitaxel. KU‐19‐19 and 5637 human bladder cancer cells were plated in six‐well (for Western blot analysis) or 96‐well (for cell proliferation assay) culture plates 1 day before treatment so they would reach about 30% confluence. The NF‐κB p65 siRNA Kit (Cell Signaling Technology) was mixed in the RPMI‐1640 medium. Cells were pre‐incubated with NF‐κB p65 siRNA for 48 h before addition of paclitaxel to each well and then incubating the plate for 48 h.

Treatment in vivo. Nude athymic BALB/c mice, 6 weeks of age with an average body weight of 20 g, were purchased from Sankyo Laboratory Service (Tokyo, Japan). Mice were housed under specific pathogen‐free conditions. All of the procedures involving animals and their care in this study were approved by the Animal Care Committee of Keio University in accordance with institutional and Japanese government guidelines for animal experiments.

All mice were inoculated subcutaneously (s.c.) on the flank with 100 μL (1 × 106 cells) of KU‐19‐19 cells. On day 6, when the animals had developed palpable tumors, the mice were randomly assigned to one of four groups, each consisting of approximately 12 animals (vehicle control, α‐TOS alone, paclitaxel alone, and their combination). The α‐TOS treatment was started on day 6 after KU‐19‐19 cell inoculation. The mice were administered either 150 mg/kg α‐TOS, suspended in 100 μL of sterile DMSO and PEG (7%DMSO/93%PEG; total 100 μL) or vehicle (7%DMSO/93%PEG; total 100 μL) daily by intraperitoneal injection with three cycles of five consecutive daily injections followed by 2 days of rest. The mice were administered 10 mg/kg paclitaxel by intravenous injection on days 8 and 15. Paclitaxel was diluted in PBS. The animals were carefully monitored, and the tumor was measured twice a week. Four weeks after tumor cell implantation, the mice were sacrificed and the tumors were collected. The tumor volume (V) was calculated according to the formula V = AB 2/2, where A is the greatest diameter and B is the diameter at the point perpendicular to A.

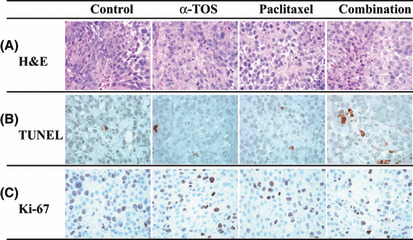

Immunostaining of the tumors for TUNEL and Ki‐67. All biopsies for histological examination were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, processed by routine methods, embedded in paraffin wax, and sectioned at 4 μm. Immunohistochemical staining was carried out on sections of formalin‐fixed paraffin wax‐embedded tissue.

Apoptosis was measured by TUNEL assay using a commercially available apoptosis in situ detection kit (S7100; Chemicon, Temecula, CA). To determine the proliferative activity, Ki‐67 immunostaining was performed using an anti‐Ki‐67 monoclonal antibody (MIB‐1; Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA). Visualization of the immunoreaction was performed with 0.06% 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Sigma Chemical). A dark accumulation of DAB in the nuclei was judged to indicate a positive reaction for TUNEL and Ki‐67. The TUNEL positive cells were counted in 10 different microscopic fields of at least three different sections from each group, and the apoptotic index was calculated as the average number of TUNEL positive cells in a microscopic field at a × 400 magnification. The percentage of cancer cells with nuclei stained for Ki‐67, that is, the Ki‐67 index, was calculated for each section on the basis of about 2000 cancer cell nuclei.( 36 )

Statistical analysis. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. The tumor volume in nude mice was compared among the groups using one‐way anova combined with Bonferroni’s t‐test. Other statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t‐test. P‐values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Combination index (CI) analysis provided qualitative measure of the extent of drug interaction. A CI of less than, equal to, and more than 1 indicates synergy, additivity, and antagonism, respectively.( 37 )

Results

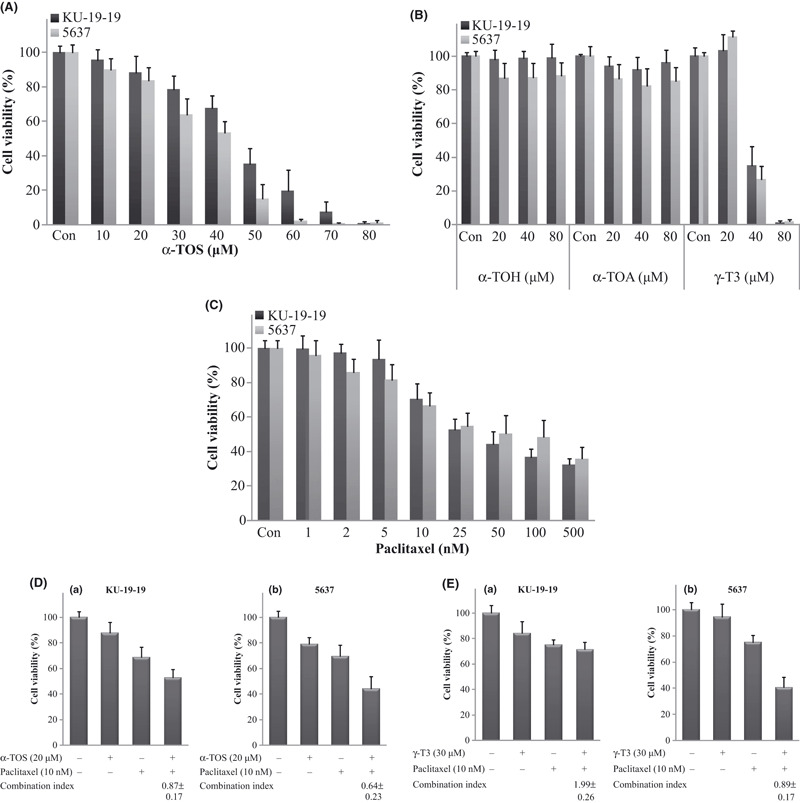

Antiproliferation effect of vitamin E derivatives and paclitaxel. We conducted dose‐ and time‐response studies on the proliferation of KU‐19‐19 and 5637 human bladder cancer cells in vitro to determine the effects of α‐TOS on bladder cancer growth. After 48 h of incubation, α‐TOS inhibited cell growth in a dose‐dependent manner in KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells (Fig. 1A). And α‐TOS inhibited cell growth in a time‐dependent manner (data not shown). We also tested the effects of vitamin E derivatives (α‐TOH, α‐TOA, and γ‐T3) for 48 h at increasing dosage (low, 20 μm; medium, 40 μm; and high, 80 μm). γ‐T3 significantly inhibited cell proliferation in KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells (Fig. 1B). Meanwhile, α‐TOH and α‐TOA did not exhibit any cytotoxic effects in KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Cell viability was measured by WST‐1 assay. Control cells were treated with the same concentration of ethanol as used in vitamin E succinate (α‐TOS) treatment. Each value represents the mean ± SD of at least three individual experiments. (A) Cytotoxic effects of α‐TOS on bladder cancer cell lines. The KU‐19‐19 or 5637 cells were treated with various concentrations of α‐TOS for 48 h. (B) Cytotoxic effects of vitamin E derivatives (α‐TOH, α‐TOA, and γ‐T3) on bladder cancer cell lines. The KU‐19‐19 or 5637 cells were treated with various concentrations of vitamin E derivatives for 48 h. (C) Cytotoxic effects of paclitaxel on bladder cancer cell lines. The KU‐19‐19 or 5637 cells were treated with various concentrations of paclitaxel for 48 h. (D) Cytotoxic effects of combination therapy on bladder cancer cell lines. (a) KU‐19‐19 cells were treated with α‐TOS and paclitaxel for 48 h. (b) 5637 cells were treated with α‐TOS and paclitaxel for 48 h. (E) Cytotoxic effects of combination therapy on bladder cancer cell lines. (a) KU‐19‐19 cells were treated with γ‐T3 and paclitaxel for 48 h. (b) 5637 cells were treated with γ‐T3 and paclitaxel for 48 h.

Paclitaxel induced a significant decrease in cell viability after 48 h of incubation in both KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells in a dose‐dependent manner (Fig. 1C).

Combination treatment of α‐TOS and paclitaxel in KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells. In KU‐19‐19 cells, the mean cell viability values (relative to control) of the treatment with α‐TOS alone (20 μm), paclitaxel alone (10 nm), and their combination were 87.7 ± 8.5%, 68.9 ± 7.7%, and 53.1 ± 6.1%, respectively (Fig. 1Da). In 5637 cells, corresponding values were 78.9 ± 5.5%, 69.4 ± 9.1%, and 44.4 ± 9.4%, respectively (Fig. 1Db). The CI values of α‐TOS and paclitaxel combination treatment in KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells were 0.87 ± 0.17 and 0.64 ± 0.23, respectively; therefore, a synergistic effect was observed in both KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells treated with the combination compared with those treated with α‐TOS alone or paclitaxel alone (P < 0.05).

We also examined combined treatment with other vitamin E derivatives (α‐TOH, α‐TOA, and γ‐T3) and paclitaxel. In the combination treatment, γ‐T3 and paclitaxel treatment had no additive effects in KU‐19‐19 cells, while on the other hand, γ‐T3 and paclitaxel combination treatment had synergistic effects in 5637 cells (Fig. 1E). In 5637 cells, the mean cell viability values (relative to control) of the treatment with γ‐T3 alone (30 μm), paclitaxel alone (10 nm), and their combination were 94.6 ± 9.7%, 75.2 ± 5.2%, and 40.5 ± 7.6%, respectively. The CI value of γ‐T3 and paclitaxel combination treatment in 5637 cells was 0.89 ± 0.17 (P < 0.05). Furthermore, α‐TOH/α‐TOA and paclitaxel combination treatment had no synergistic/additive effects in either KU‐19‐19 or 5637 cells (data not shown). These results demonstrated that vitamin E derivatives administered in combination with paclitaxel had different therapeutic effects in bladder cancer cells.

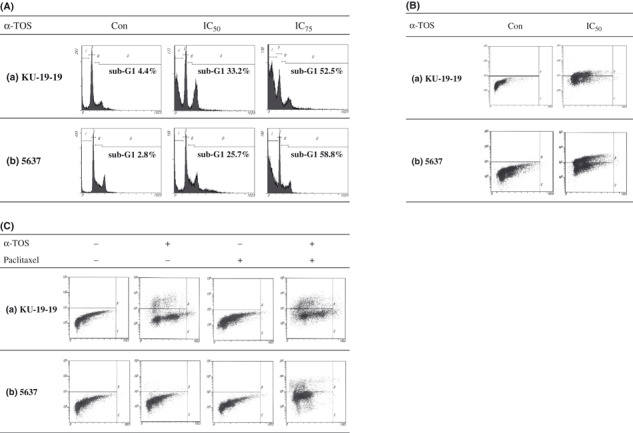

Cell cycle and apoptosis assay. We examined the cell cycle distribution after α‐TOS treatment. Flow cytometry studies showed that the both KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells responded to α‐TOS treatment and accumulated in the sub‐G1 phase of the cell cycle in a dose‐dependent manner (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Flow cytometric analysis was performed. Control cells were treated with the same concentration of ethanol as used in vitamin E succinate (α‐TOS) treatment. The doses to suppress 50% cell growth (IC50) for 24 h in KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells were 58 μm and 47 μm, respectively. The doses to suppress 75% cell growth (IC75) for 24 h in KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells were 71 μm and 60 μm, respectively. (A) Flow cytometric analysis was performed using BrdU assay for detecting cell cycle. KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells were treated with α‐TOS for 24 h. (B) Flow cytometric analysis was performed using TUNEL assay for detecting apoptosis. KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells were treated with α‐TOS for 24 h. Upper left quadrants of each graph represent the apoptotic cell populations. (C) Flow cytometric analysis was performed using TUNEL assay for detecting apoptosis. KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells were treated with α‐TOS and paclitaxel for 72 h. Upper left quadrants of each graph represent the apoptotic cell populations.

In the TUNEL assay, the apoptotic indexes induced by α‐TOS treatment and vehicle control were 38.4% and 0.0% in KU‐19‐19 cells and 49.5% and 0.1% in 5637 cells, respectively (Fig. 2B). In KU‐19‐19 cells, the apoptotic indexes induced by combination, α‐TOS alone, paclitaxel alone, and control were 28.2%, 18.7%, 0.0%, and 0.0%, respectively (Fig. 2Ca). The combination treatment resulted in a significantly higher level of apoptosis compared to α‐TOS alone. In 5637 cells, the apoptotic indexes induced by the combination, α‐TOS alone, paclitaxel alone, and control were 14.8%, 1.0%, 0.1%, and 0.1%, respectively (Fig. 2Cb). In 5637 cells, apoptosis was only detected by combination treatment.

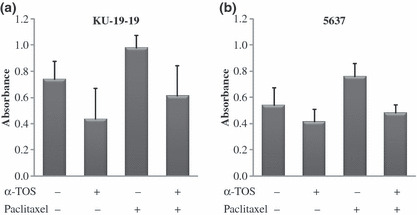

NF‐κB activity. We then evaluated NF‐κB activity in bladder cancer cells following α‐TOS, paclitaxel, and the combination treatment. In KU‐19‐19 cells, the absorbance values at 450 nm for the control, α‐TOS, paclitaxel, and combination treatment were 0.738 ± 0.140, 0.437 ± 0.233, 0.979 ± 0.097, and 0.611 ± 0.234, respectively (Fig. 3a). In 5637 cells, the corresponding values for the control, α‐TOS, paclitaxel, and combination treatment were 0.540 ± 0.137, 0.414 ± 0.098, 0.759 ± 0.100, and 0.480 ± 0.066, respectively (Fig. 3b). NF‐κB activity was reduced in both KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells treated with α‐TOS alone compared with control. Meanwhile, NF‐κB was activated by paclitaxel treatment in both cell lines. The activated NF‐κB activity induced by paclitaxel was significantly reduced by the addition of α‐TOS (P < 0.05 for both cell lines).

Figure 3.

Detection of nuclear factor‐kappa B (NF‐κB) activity. Each value represents the mean derived from at least three individual experiments; bars, ±SD. (a) KU‐19‐19 and (b) 5637 cells were treated with vitamin E succinate (α‐TOS) and/or paclitaxel. Trans‐AM assay was performed, and NF‐κB activity was detected by ELISA.

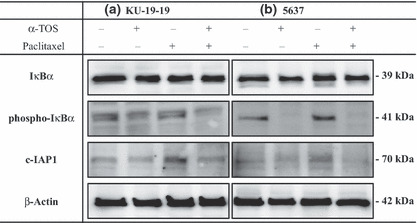

Western blot analysis. The effect of α‐TOS on NF‐κB signalling was further explored by examining the expression of other upstream regulators, such as IκBα and phospho‐IκBα. In α‐TOS treated KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells, a decrease in the level of the phosphorylated IκBα was observed. These results indicate that α‐TOS inhibited NF‐κB activity through the suppression of phosphorylation of IκBα. In KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells, paclitaxel induced the expression of c‐IAP1 protein and the combination of α‐TOS and paclitaxel inhibited the expression of it. We demonstrated that α‐TOS co‐treatment with paclitaxel enhanced cell apoptosis through down‐regulation of pro‐survival proteins (phospho‐IκBα) and anti‐apoptotic proteins (c‐IAP1) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells were pre‐incubated with 40 μm of vitamin E succinate (α‐TOS) for 3 h before addition of 10 nm paclitaxel, and then incubating the dish for 24 h. Using Western blotting, we demonstrated that α‐TOS co‐treatment with paclitaxel for 24 h enhanced KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells apoptosis through down‐regulation of pro‐survival proteins (phospho‐IκBα) and anti‐apoptotic proteins (c‐IAP1).

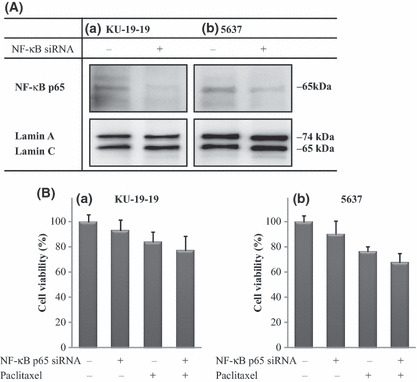

Treatment with NF‐κB p65 siRNA and paclitaxel. Using Western blotting, we confirmed that NF‐κB p65 expression was suppressed by NF‐κB p65 siRNA (Fig. 5A). In KU‐19‐19 cells, the mean cell viability values (relative to control) of the treatment with NF‐κB p65 siRNA alone (100 nm), paclitaxel alone (10 nm), and their combination were 93.3 ± 8.3%, 84.2 ± 7.9%, and 77.4 ± 11.4%, respectively. In 5637 cells, the corresponding values were 90.5 ± 10.3%, 76.4 ± 3.8%, and 68.0 ± 6.9%, respectively (Fig. 5B). The combination of NF‐κB p65 siRNA and paclitaxel showed additive effects compared with those treated with NF‐κB p65 siRNA alone or paclitaxel alone. However, the combination of NF‐κB p65 siRNA and paclitaxel did not show synergistic effects in this experiment.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of nuclear factor‐kappa B (NF‐κB) p65 expression and cell proliferation by simultaneous treatment with NF‐κB p65‐specific siRNA and paclitaxel. (A) NF‐κB p65 Western blot analysis after 48 h treatment. NF‐κB p65 expression was suppressed by NF‐κB p65 siRNA. Expression of Lamin A/C was assessed as an internal loading control for nuclear protein lysate. (B) Cell viability was measured by WST‐1 assay. Each value represents the mean ± SD of the percentage of cell viability. KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells were pre‐incubated with 100 nm NF‐κB p65 siRNA for 48 h before addition of 10 nm paclitaxel, and then incubating the dish for 48 h.

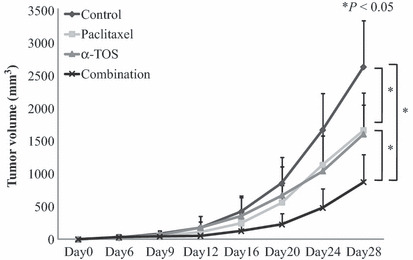

Effects of α‐TOS and/ or paclitaxel on KU‐19‐19 tumors in nude mice. As shown in Figure 6 and Table 1, α‐TOS, paclitaxel and combination treatments significantly suppressed tumor growth in mice to 61.0%, 63.3% and 33.1%, respectively, of the tumor volume in the control group on day 28 after implantation (P < 0.05). Significant differences in tumor volume were observed between the control and the combination group as early as day 12, between the control group and paclitaxel‐treated group as early as day 20, and between the control and α‐TOS‐treated group as early as day 24 after tumor implantation. Mice treated with the combination treatment, α‐TOS alone, or paclitaxel alone did not exhibit any loss of body weight on day 28.

Figure 6.

Efficacy of vitamin E succinate (α‐TOS) and paclitaxel on tumor growth in a mouse xenograft model of bladder cancer. KU‐19‐19 cells (1 × 106) were implanted in the flank of nude mice. Mice (n = 12 in each group) were treated with α‐TOS alone, paclitaxel alone, their combination, or vehicle control. α‐TOS (150 mg/kg/day) was administered via an intraperitoneal injection from day 6 to day 24 (total 15 times), and paclitaxel (10 mg/kg) was administered intravenously on day 8 and day 15 after tumor implantation. Points, mean tumor volume (mm3); bars, +SD.

Table 1.

Tumor volume, apoptotic index, and proliferation index in mouse xenograft tumors harvested 28 days after tumor implantation from mice treated with α‐TOS and/or paclitaxel (mean ± SD)

| Tumor volume (mm3) | Apoptotic index | Proliferation index (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 2610 ± 708 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 68.5 ± 2.7 |

| α‐TOS | 1591 ± 634* | 3.1 ± 0.4* | 53.4 ± 7.5* |

| Paclitaxel | 1653 ± 390* | 4.9 ± 2.2* | 40.2 ± 6.3* |

| Combination | 864 ± 422*,**, *** | 8.1 ± 1.5*,**,*** | 39.2 ± 7.1*,** |

*P < 0.05 compared with control; **P < 0.05 compared with α‐TOS; ***P < 0.05 compared with paclitaxel. α‐TOS, vitamin E succinate.

Apoptotic and proliferation index in KU‐19‐19 tumors. The apoptotic index of the tumor was significantly increased in the α‐TOS‐treated group, paclitaxel‐treated group, and combination group compared to the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 1, Fig. 7), and the apoptotic index in the combination group differed significantly from that in the α‐TOS‐treated group and paclitaxel‐treated group (P < 0.05). The proliferation index of the tumor was significantly decreased in the α‐TOS‐treated group, paclitaxel‐treated group, and the combination group compared to the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 1, Fig. 7). Moreover, the proliferation index in the combination group differed significantly from that in the α‐TOS group (P < 0.05). However, the proliferation index in the combination group did not differ significantly from that in the paclitaxel group.

Figure 7.

Immunohistochemical study of KU‐19‐19 xenograft tumors from mice treated with vitamin E succinate (α‐TOS) and/or paclitaxel. (A) Hematoxylin–eosin (H&E) staining of KU‐19‐19 xenograft tumors. (B) TUNEL staining of KU‐19‐19 xenograft tumors. (C) Ki‐67 staining of KU‐19‐19 xenograft tumors. Magnification, ×400.

Discussion

Bladder cancer is one of the most aggressive epithelial tumors characterized by a high rate of early systemic dissemination. Patients with metastatic bladder cancer are routinely treated with systemic chemotherapy such as M‐VAC regimen, particularly in the setting of unresectable, diffusely metastatic, measurable disease; however, the response rates remain inadequate. Despite continuous efforts to identify and develop even more effective chemotherapies for advanced bladder cancer, not all patients with advanced disease will respond to therapy. Therefore, a new strategy that includes the enhancement of cytotoxicity and reduction of side effects would be a very important breakthrough in the management of advanced bladder cancer.

In the present study, we first evaluated the cytotoxic effect of α‐TOS in bladder cancer cells. α‐TOS inhibited KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells proliferation in a dose‐ and time‐dependent manner in vitro. These findings are compatible with previously published α‐TOS studies for other malignancies. The results of the TUNEL assay revealed that the apoptotic indexes were induced by α‐TOS alone in both KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells. The mechanism by which α‐TOS decreases tumor proliferation is not entirely clear; however, several possible pathways, including NF‐κB inhibition of α‐TOS, have been studied. We have showed that α‐TOS has potent inhibitory effects on NF‐κB activation and produces significant decreases in cell viability. For combination treatment in vitro, α‐TOS and paclitaxel treatment exhibited a synergistic/additive cytotoxic effect when compared with treatment consisting of each drug alone. Furthermore, the combination treatment induced significant apoptosis compared to control or each agent administered alone. Previous studies have shown that γ‐T3 also suppressed the NF‐κB activation by a variety of stimuli.( 38 , 39 ) For combination treatment in vitro, γ‐T3 and paclitaxel treatment exhibited a synergistic/additive cytotoxic effect in 5637 cells.

To evaluate the mechanism by which the synergistic effect of the combination occurred, we examined NF‐κB activity during these treatments. Several groups have reported that NF‐κB may protect tumor cells against apoptosis induced by anticancer drugs, such as paclitaxel.( 40 , 41 ) The activation of NF‐κB during chemotherapy is one of the crucial mechanisms for the development of chemotherapeutic resistance.( 42 ) It was confirmed that NF‐κB was activated by paclitaxel; however, the activation of NF‐κB was inhibited by pretreatment with α‐TOS in both KU‐19‐19 and 5637 cells in vitro. NF‐κB is known to regulate the expression of inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) family genes, and their overexpression in numerous tumors has been associated with tumor survival, chemoresistance, and radioresistance. We demonstrated that α‐TOS co‐treatment with paclitaxel enhances cell apoptosis through down‐regulation of pro‐survival proteins (phospho‐IκBα) and anti‐apoptotic proteins (c‐IAP1). Pretreatment with α‐TOS inhibited activation of NF‐κB induced by paclitaxel; therefore, pretreatment with α‐TOS is an attractive candidate for combination treatment with many anticancer agents, including paclitaxel, that induce activation of NF‐κB. However, the combination of NF‐κB p65 siRNA and paclitaxel did not exhibit synergistic effects in this experiment. We believe these results demonstrate that the NF‐κB inhibition by α‐TOS was a part of the mechanism in the combined α‐TOS and paclitaxel treatment. Previous studies have shown that α‐TOS inhibits tumor cell growth by a variety of mechanisms. We hypothesize that cell cycle arrest may be another crucial mechanism in the present study. In the current study, arrest at sub‐G1 phase was induced by α‐TOS. Paclitaxel is a microtubule inhibitor, and therefore reduces the ability of cancer cells to arrest at the G2/M phase. Thus, combination therapy consisting of α‐TOS and paclitaxel may induce double checkpoint arrests (sub‐G1 and G2/M arrests) in the cell cycle. However, double checkpoint arrests were not demonstrated clearly by BrdU for cell cycle analysis in this study (data not shown).

On the basis of the in vitro results, we tested the antitumor effects of α‐TOS and/or paclitaxel on KU‐19‐19 s.c. tumors inoculated into nude mice. In vivo study demonstrated a significant decrease in the tumor growth of α‐TOS treated mice compared to control mice, and then a significant decrease in tumor growth was observed in mice treated with the combination of α‐TOS and paclitaxel, compared to those treated with control, α‐TOS alone, or paclitaxel alone on day 28. α‐TOS and/or paclitaxel treatment at the dosages used was well tolerated, leading to no body weight loss in the animals compared with control (data not shown). Immunohistochemical study in a KU‐19‐19 xenograft tumor model demonstrated that the apoptotic index in tumors treated by the combination treatment was significantly increased compared to those treated with vehicle control, α‐TOS alone, or paclitaxel alone. Furthermore, the proliferation index was significantly decreased in tumors treated by the combination treatment compared to those treated with vehicle control or α‐TOS alone. These findings were compatible with the results of the in vitro study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of α‐TOS inhibiting the growth of bladder cancer cells in vitro and in vivo, and the antitumor effect of paclitaxel was potentiated by α‐TOS compared to each drug alone. These results suggest that α‐TOS plus paclitaxel has synergistic/additive effects and thus the combination could constitute a logical therapeutic strategy for bladder cancer.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate the efficacy and therapeutic potential of α‐TOS and its enhancement of chemosensitivity to paclitaxel in bladder cancer cells. α‐TOS inhibits NF‐κB activity resulting in the promotion of apoptotic mechanisms in bladder cancer cell lines and also reduces activated NF‐κB induced by paclitaxel resulting in enhanced apoptosis in vitro.α‐TOS displayed an antitumor effect and α‐TOS in combination with paclitaxel demonstrated dramatic tumor inhibition in an in vivo s.c. KU‐19‐19 tumor model. Although additional studies are needed to confirm its safety for use in clinical trials, the cytotoxic effect of α‐TOS and its enhancement of paclitaxel treatment might provide a novel strategy for advanced or metastatic bladder cancer patients.

References

- 1. Sternberg CN, Yagoda A, Scher HI et al. M‐VAC (methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin and cisplatin) for advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelium. J Urol 1988; 139: 461–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saxman SB, Propert KJ, Einhorn LH et al. Long‐term follow‐up of a phase III intergroup study of cisplatin alone or in combination with methotrexate, vinblastine, and doxorubicin in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma: a cooperative group study. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15: 2564–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roth BJ, Dreicer R, Einhorn LH et al. Significant activity of paclitaxel in advanced transitional‐cell carcinoma of the urothelium: a phase II trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 1994; 12: 2264–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Papamichael D, Gallagher CJ, Oliver RT, Johnson PW, Waxman J. Phase II study of paclitaxel in pretreated patients with locally advanced/metastatic cancer of the bladder and ureter. Br J Cancer 1997; 75: 606–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sternberg CN, Calabro F, Pizzocaro G, Marini L, Schnetzer S, Sella A. Chemotherapy with an every‐2‐week regimen of gemcitabine and paclitaxel in patients with transitional cell carcinoma who have received prior cisplatin‐based therapy. Cancer 2001; 92: 2993–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kanai K, Kikuchi E, Ohigashi T et al. Gemcitabine and paclitaxel chemotherapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma in patients who have received prior cisplatin‐based chemotherapy. Int J Clin Oncol 2008; 13: 510–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Suffness M. Is taxol a surrogate for a universal regulator of mitosis? In Vivo 1994; 8: 867–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fan W. Possible mechanisms of paclitaxel‐induced apoptosis. Biochem Pharmacol 1999; 57: 1215–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kelloff GJ, Crowell JA, Boone CW et al. Clinical development plan: vitamin E. J Cell Biochem Suppl 1994; 20: 282–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Israel K, Sanders BG, Kline K. RRR‐alpha‐tocopheryl succinate inhibits the proliferation of human prostatic tumor cells with defective cell cycle/differentiation pathways. Nutr Cancer 1995; 24: 161–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Simmons‐Menchaca M, Qian M, Yu W, Sanders BG, Kline K. RRR‐alpha‐tocopheryl succinate inhibits DNA synthesis and enhances the production and secretion of biologically active transforming growth factor‐beta by avian retrovirus‐transformed lymphoid cells. Nutr Cancer 1995; 24: 171–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Israel K, Yu W, Sanders BG, Kline K. Vitamin E succinate induces apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells: role for Fas in vitamin E succinate‐triggered apoptosis. Nutr Cancer 2000; 36: 90–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weber T, Lu M, Andera L et al. Vitamin E succinate is a potent novel antineoplastic agent with high selectivity and cooperativity with tumor necrosis factor‐related apoptosis‐inducing ligand (Apo2 ligand) in vivo. Clin Cancer Res 2002; 8: 863–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yin Y, Ni J, Chen M, DiMaggio MA, Guo Y, Yeh S. The therapeutic and preventive effect of RRR‐alpha‐vitamin E succinate on prostate cancer via induction of insulin‐like growth factor binding protein‐3. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13: 2271–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gu X, Song X, Dong Y et al. Vitamin E succinate induces ceramide‐mediated apoptosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14: 1840–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Prasad KN, Cohrs RJ, Sharma OK. Decreased expressions of c‐myc and H‐ras oncogenes in vitamin E succinate induced morphologically differentiated murine B‐16 melanoma cells in culture. Biochem Cell Biol 1990; 68: 1250–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Malafa MP, Fokum FD, Mowlavi A, Abusief M, King M. Vitamin E inhibits melanoma growth in mice. Surgery 2002; 131: 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Venkateswaran V, Fleshner NE, Klotz LH. Modulation of cell proliferation and cell cycle regulators by vitamin E in human prostate carcinoma cell lines. J Urol 2002; 168: 1578–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ni J, Chen M, Zhang Y, Li R, Huang J, Yeh S. Vitamin E succinate inhibits human prostate cancer cell growth via modulating cell cycle regulatory machinery. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003; 300: 357–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Malafa MP, Fokum FD, Smith L, Louis A. Inhibition of angiogenesis and promotion of melanoma dormancy by vitamin E succinate. Ann Surg Oncol 2002; 9: 1023–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dong LF, Swettenham E, Eliasson J et al. Vitamin E analogues inhibit angiogenesis by selective induction of apoptosis in proliferating endothelial cells: the role of oxidative stress. Cancer Res 2007; 67: 11906–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dalen H, Neuzil J. Alpha‐tocopheryl succinate sensitises a T lymphoma cell line to TRAIL‐induced apoptosis by suppressing NF‐kappaB activation. Br J Cancer 2003; 88: 153–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Crispen PL, Uzzo RG, Golovine K et al. Vitamin E succinate inhibits NF‐kappaB and prevents the development of a metastatic phenotype in prostate cancer cells: implications for chemoprevention. Prostate 2007; 67: 582–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Charpentier A, Groves S, Simmons‐Menchaca M et al. RRR‐alpha‐tocopheryl succinate inhibits proliferation and enhances secretion of transforming growth factor‐beta (TGF‐beta) by human breast cancer cells. Nutr Cancer 1993; 19: 225–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yu W, Heim K, Qian M, Simmons‐Menchaca M, Sanders BG, Kline K. Evidence for role of transforming growth factor‐beta in RRR‐alpha‐tocopheryl succinate‐induced apoptosis of human MDA‐MB‐435 breast cancer cells. Nutr Cancer 1997; 27: 267–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Charpentier A, Simmons‐Menchaca M, Yu W et al. RRR‐alpha‐tocopheryl succinate enhances TGF‐beta 1, ‐beta 2, and ‐beta 3 and TGF‐beta R‐II expression by human MDA‐MB‐435 breast cancer cells. Nutr Cancer 1996; 26: 237–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Turley JM, Fu T, Ruscetti FW, Mikovits JA, Bertolette DC III, Birchenall‐Roberts MC. Vitamin E succinate induces Fas‐mediated apoptosis in estrogen receptor‐negative human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 1997; 57: 881–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yu W, Israel K, Liao QY, Aldaz CM, Sanders BG, Kline K. Vitamin E succinate (VES) induces Fas sensitivity in human breast cancer cells: role for Mr 43,000 Fas in VES‐triggered apoptosis. Cancer Res 1999; 59: 953–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Prasad KN, Edwards‐Prasad J. Effects of tocopherol (vitamin E) acid succinate on morphological alterations and growth inhibition in melanoma cells in culture. Cancer Res 1982; 42: 550–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fleshner N, Fair WR, Huryk R, Heston WD. Vitamin E inhibits the high‐fat diet promoted growth of established human prostate LNCaP tumors in nude mice. J Urol 1999; 161: 1651–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McCormick DL, Rao KV. Chemoprevention of hormone‐dependent prostate cancer in the Wistar‐Unilever rat. Eur Urol 1999; 35: 464–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Neuzil J, Weber T, Gellert N, Weber C. Selective cancer cell killing by alpha‐tocopheryl succinate. Br J Cancer 2001; 84: 87–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Prasad KN, Kumar B, Yan XD, Hanson AJ, Cole WC. Alpha‐tocopheryl succinate, the most effective form of vitamin E for adjuvant cancer treatment: a review. J Am Coll Nutr 2003; 22: 108–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Venkateswaran V, Fleshner NE, Sugar LM, Klotz LH. Antioxidants block prostate cancer in lady transgenic mice. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 5891–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tachibana M, Miyakawa A, Nakashima J et al. Constitutive production of multiple cytokines and a human chorionic gonadotrophin beta‐subunit by a human bladder cancer cell line (KU‐19‐19): possible demonstration of totipotential differentiation. Br J Cancer 1997; 76: 163–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Koide N, Nishio A, Hiraguri M, Hanazaki K, Adachi W, Amano J. Coexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor and p53 protein in squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96: 1733–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhao L, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Evaluation of combination chemotherapy: integration of nonlinear regression, curve shift, isobologram, and combination index analyses. Clin Cancer Res 2004; 10: 7994–8004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ahn KS, Sethi G, Krishnan K, Aggarwal BB. Gamma‐tocotrienol inhibits nuclear factor‐kappaB signaling pathway through inhibition of receptor‐interacting protein and TAK1 leading to suppression of antiapoptotic gene products and potentiation of apoptosis. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 809–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yap WN, Chang PN, Han HY et al. Gamma‐tocotrienol suppresses prostate cancer cell proliferation and invasion through multiple‐signalling pathways. Br J Cancer 2008; 99: 1832–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Das KC, White CW. Activation of NF‐kappaB by antineoplastic agents. Role of protein kinase C. J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 14914–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu GH, Wang SR, Wang B, Kong BH. Inhibition of nuclear factor‐kappaB by an antioxidant enhances paclitaxel sensitivity in ovarian carcinoma cell line. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2006; 16: 1777–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bharti AC, Aggarwal BB. Nuclear factor‐kappa B and cancer: its role in prevention and therapy. Biochem Pharmacol 2002; 64: 883–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]