Stroke is the second most common cause of death worldwide, exceeded only by heart disease.1 Coincident with the emergence of prevention strategies, incidence of stroke is declining dramatically in developed countries. The prevention of stroke is an obligation facing everyone involved with delivering health care.

Summary points

Managing the risk factors of hypertension, tobacco, and hyperglycaemia reduces the risk of stroke

Managing hyperglycaemia will diminish the severity of strokes

Warfarin prevents stroke in non-valvular atrial fibrillation

Aspirin is the first choice of platelet inhibitors for stroke prevention

Endarterectomy prevents stroke when symptoms are due to severe stenosis; with moderate stenosis the benefit is muted

Endarterectomy is of uncertain benefit for asymptomatic carotid stenosis

Manageable risk factors for stroke

Prospective population studies and retrospective case series have identified modifiable risk factors important for ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke.

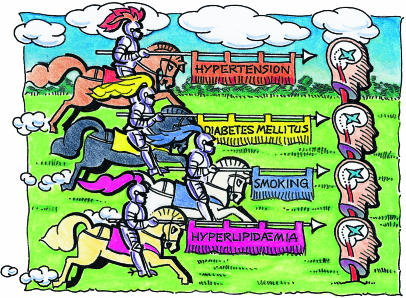

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse of stroke display the banners of hypertension, tobacco, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidaemia.2 All are responsible for cerebral arteriosclerosis. Transient ischaemic events are powerful predictors of stroke. Coronary artery disease and atrial fibrillation increase stroke risk. Compounds lowering cholesterol, the “statins,” reduce the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke.3

At no age and in neither sex is a systolic blood pressure above 160 mm Hg and a diastolic pressure above 90 mm Hg acceptable. Even elderly subjects and heavy smokers reduce the risk of stroke by abandoning cigarettes.4

Control of insulin dependent diabetes has not been shown to reduce stroke.5 A stroke in the presence of hyperglycemia is more disabling.

Family history of stroke requires the Four Horsemen be sought and managed in the early decades of life. Fatalistic attitudes are wrong. Genetics deals the cards. The play can be determined by environmental influences.

Coagulation abnormalities and homocysteinaemia add to the likelihood of early stroke but are manageable.6

Anticoagulants in stroke prevention

Seven randomised trials reported that adjusted doses of warfarin prevent stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation.7 From meta-analysis, a 64% relative risk reduction of stroke favoured warfarin over placebo,2 without increase in major bleeding.8,9 (The target international normalised ratio is 2-3.)

Compared with aspirin, the overall relative risk reduction of 48% favours warfarin.7 Compared with placebo, aspirin reduces the stroke risk by 22%.

Warfarin decreased the rate of stroke in all subgroups of non-valvular atrial fibrillation except in younger patients without risk factors.8,9 Fixed dose therapy in patients with international normalised ratios 1.2-1.5 did not prevent strokes.9

Under age 65, patients without a history of hypertension, cerebral ischaemic events, or diabetes are at lowest risk of stroke, and such patients should receive aspirin. Aspirin may be appropriate in other “low risk” patients without recent congestive heart failure or previous thromboembolism and whose systolic blood pressure is <160 mm Hg, and for women over 75 years.8

Untreated patients over 75 years face the worst prognosis and potentially should benefit most from anticoagulant therapy but have the highest risk of haemorrhagic complications. Patients must be carefully monitored to keep the international normalised ratio below 3.0.

Risk evaluation will determine the need for a lifetime of warfarin therapy. Randomised trials, case series, and a meta-analysis favour the use of heparin and warfarin to prevent stroke after acute myocardial infarction.10–12 For patients with cerebral ischaemia after myocardial infarction, 3-6 months of anticoagulant therapy is recommended. For patients without cerebral ischaemia, use of anticoagulants is discretionary.

In patients with arterial disease causing ischaemic events, when platelet inhibitors fail it is common practice to switch to anticoagulants. Ongoing trials may confirm this empirical indication.13 At present it cannot be recommended.

SUE SHARPLES

Anticoagulants have been evaluated in patients immediately after acute strokes. One acute stroke trial (n=308) compared two doses of low molecular weight heparin with placebo within 48 hours of onset of stroke.14 A significant dose dependent reduction in death and dependency was reported at six months. These observations were not confirmed in a factorial, 19 435 patient trial of low or medium unfractionated heparin.15 The higher dose of heparin led to more transfusions, fatal extracranial bleeds, and haemorrhagic strokes. Another acute stroke trial of low molecular weight heparin versus placebo had negative results.16

High rates of bleeding complications (particularly intracerebral haemorrhage) led to termination of a trial comparing anticoagulant therapy (ratio 3.0-4.5) with low dose aspirin in patients with recent (less than six months) ischaemic events.17 Major bleeding complications increased steeply with the intensity of anticoagulation.

The routine use of anticoagulants in non-cardiac ischaemic stroke patients is not recommended.

Platelet inhibitors in stroke prevention

Six platelet inhibitors have been evaluated in stroke prevention. Suloctidil and sulphinpyrazone were ineffective.

Dipyridamole

Dipyridamole was evaluated first. Negative benefit was reported in 169 patients. In three subsequent trials 1575 patients with transient ischaemic attacks or minor stroke were randomised to receive either aspirin in doses of 900-1300 mg or dipyridamole with aspirin. The combination was not superior to aspirin alone. A recent study claims benefit for the combination of dipyridamole and 50 mg of aspirin daily over aspirin or dipyridamole alone.18 The investigation has been criticised and its acceptance was not enthusiastic.19–21 The previously compared dose of aspirin was reduced 20-fold, lower than any dose proven useful in a placebo controlled, stroke prevention trial. The placebo arm raised ethical concerns.

Dipyridamole is not recommended, alone or with aspirin.

Aspirin

A seminal trial of factorial design (n=585) gave either 1300 mg aspirin, sulphinpyrazone, both, or double placebo. A 31% relative risk reduction of stroke and death favoured aspirin. Subsequently 15 trials have utilised aspirin against placebo in patients with transient ischaemic attacks and stroke.22,23

Aspirin prevents stroke in both sexes. The relative risk reduction averages 25%.

Minimal complications after 11 000 patient years of aspirin administration indicate a satisfactory tolerance and safety for enteric coated aspirin (North American symptomatic carotid endarterectomy trial, unpublished data). Haemorrhagic side effects are not dose related. These observations mute the importance of the uncertainty about dosage.

The optimum dose for stroke prevention has not been determined by direct comparisons. Indirect comparisons provide no evidence that low or high doses are superior to each other. From indirect evidence we recommend 650-900 mg of aspirin daily for patients threatened by stroke.

Ticlopidine

Two trials of ticlopidine showed benefit. Though ticlopidine is an effective drug in stroke prevention, its superiority to aspirin is modest, and it has serious disadvantages. It causes diarrhoea in up to 20% of subjects, and 5% or more cannot tolerate this side effect. Complicating bone marrow suppression has been fatal in 16% of the patients in which it was reported.24 Despite appropriate monitoring, 33% of 60 patients with complicating thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura died.25

Clopidogrel

Clopidogrel is a chemical relative to ticlopidine. In a trial of 19 185 patients it was tested against 325 mg of aspirin daily for patients with stroke, myocardial infarction, or peripheral vascular disease.26 The relative risk reduction of combined vascular events was 8.7% favouring clopidogrel. The absolute risk reduction of 0.5% due to clopidogrel is narrowly better than that of aspirin.

Clopidogrel must be given to 200 patients to prevent one end point per year more than with aspirin.27,28 Reduction for the combination of stroke and death was not statistically significant.28 Two thirds of the patients in the trial had not experienced recent cerebral ischaemia. The inclusion of 6452 patients with symptoms of peripheral arterial disease seemed to tip the scales towards marginal benefit for the combination of mixed system end points.

There was less diarrhoea than with ticlopidine. Reversible bone marrow suppression occurred in 0.2% of patients.

The daily cost in the United States of $2.40 (£1.50) compares with a cost of $0.17 for aspirin. Clopidogrel does not replace aspirin as the drug of first choice. Because of the serious and fatal side effects from ticlopidine, clopidogrel becomes the drug of second choice if symptoms persist despite aspirin or if aspirin is not tolerated.

Carotid endarterectomy in stroke prevention

In 1954 a patient with transient ischaemic attacks responded to segmental resection of a stenosed carotid artery.29 Subsequently, endarterectomy was performed with increasing frequency. By 1985, 107 000 endarterectomies were done in the United States. Questions were raised about the appropriateness of the extensive use of this procedure.30 Complication rates ranged from low to unacceptably high.

Symptomatic disease

The European carotid surgery trial and the North American symptomatic carotid endarterectomy trial involved 5909 patients.31,32 Best medical care was randomly assigned to 2662 patients and carotid endarterectomy to 3247 patients. In patients with retinal or hemisphere symptoms attributable to “severe” (70-99%) carotid stenosis, endarterectomy was superior to medical care alone. The number of patients requiring endarterectomy to prevent one stroke in 2 years is 6-8 (table).

In published results, different methods were used to calculate the degree of stenosis.31,32 “Severe” is 70% by North American measurements and 85% by European measurements. Patients with moderate stenosis (North American 50-69%, European 75%-84%) benefit less. The number needed to treat by endarterectomy in the North American symptomatic carotid endarterectomy trial becomes 19.32 Symptomatic patients with minimal degrees of stenosis (North American below 50%; European below 75%) receive no benefit from endarterectomy, or perhaps even harm.

The best results from endarterectomy for patients with moderate (50-69%) stenosis were observed with hemisphere rather than retinal symptoms, non-disabling strokes rather than transient events, and male sex.32 The operative risk doubles with occlusion of the artery opposite to the symptoms, thrombus visible in the artery, a history of diabetes, an appropriate lesion on computerised tomography, or diastolic blood pressure above 90 mm Hg.

The benefit from endarterectomy relates to complication rates. Reported benefits were predicated on operative risks of stroke or death of 7.5% in the European trial and 6.5% in the North American trial. If the endarterectomy rate exceeds the disabling stroke and death rate by as little as 2%, benefit disappears. Evidence is lacking to support the performance of endarterectomy for so called non-specific or non-hemisphere symptoms.

Both trials used conventional angiography. The identification of comparably “severe” or “moderate” stenosis by non-invasive methods is imperfect. Screening will include ultrasound or magnetic resonance arterial imaging.

In capable hands, angiography carries a risk of disabling stroke of 0.1%. With expert surgeons endarterectomy carries a 2.0% risk of disabling stroke and death.33 A 20-fold increase of risk from endarterectomy compared with angiography persuades us that angiography is an essential prelude. In many centres ultrasonography alone probably leads to inappropriate endarterectomy in as many as 30% of patients.34

Asymptomatic disease

Endarterectomy for asymptomatic patients remains controversial. Asymptomatic disease carries a substantially lower risk of stroke than when symptoms develop. Three negative trials and one positive trial have been published. A fifth is ongoing.

To benefit asymptomatic individuals the perioperative risk of endarterectomy must be no higher than 3%. In three of the four randomised trials this limit was exceeded. The largest of the completed trials (n=1662), the asymptomatic carotid atherosclerosis study, had a low (2.6%) perioperative risk of stroke and death.35 The five year risks were 11% in the medical group and 5.1% in the endarterectomy group. The absolute reduction of stroke favouring endarterectomy was 1% annually. Disabling strokes were not prevented.

Subgroup analysis found no benefit for women. The numbers were small, and outcome events were few. The perioperative risk of stroke or death was 3.3% for women.

In all trials with asymptomatic subjects the numbers needed to receive endarterectomy to prevent one stroke in two years are unacceptably high (table). The large observational studies of asymptomatic disease have identified that below 80% stenosis the annual stroke risk is 1% or less.36,37

Despite the modest reported benefits some observers believe that it is appropriate to operate on any asymptomatic patient with a stenosis above 60%. An American Heart Association consensus statement supports this liberal approach.38 Statistical significance has been equated with clinical importance. We believe a conservative approach is in order and that future disciplined research, including the study of the impact of risk factors, is needed.39–42

Patients with asymptomatic stenosis on one side and a complete carotid occlusion on the other may benefit from endarterectomy. Validation of this practice requires careful data from future randomised studies.

Endarterectomy is commonly performed for asymptomatic stenosis as a prelude to coronary artery bypass grafting. The risks are additive. No convincing data are available to validate this practice.

Most asymptomatic patients are probably best treated by medical care. The aspirin and carotid endarterectomy trial (n=1521) records a stroke and death rate of 4.6% in asymptomatic subjects (unpublished data). Comparable rates from recent randomised trials or community observations range from 4.0% to 6.9%.43,44 When the risk is this high there is negative benefit (table).

Conclusions

A lifetime commitment to managing risk factors is the pre-eminent therapeutic requirement for all patients threatened with stroke.

Aspirin is the platelet inhibitor of first choice for patients experiencing transient ischaemic attacks or minor stroke related to cerebral arteriosclerosis.

Clopidogrel is recommended for patients with a known intolerance to aspirin or if symptoms recur despite use of aspirin.

Should clopidogrel fail, the cautious administration of ticlopidine is an acceptable alternative.

Long term warfarin therapy should be considered for patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Patients at lower risk should receive aspirin.

Carotid endarterectomy is recommended for patients with severe carotid stenosis producing focal symptoms.

Careful selection will allow some patients with symptoms and moderate stenosis to be considered for endarterectomy.

In many institutions, endarterectomy will not benefit asymptomatic patients. Current guidelines about its usefulness are unduly optimistic.

Institutions should make available the results of independent audits of surgical complications of stroke and death from endarterectomy.45 The line between success and failure is a narrow one.

Table.

Number needed to treat by endarterectomy to prevent one stroke in 2 years in patients with carotid stenosis

| No of patients in specified trial | Medical risk (%) at 2 years | Surgical risk (%) at 2 years | Risk difference (%) | Relative risk reduction (%) | No need to treat* | Perioperative stroke and death rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptomatic patients: | |||||||

| 70-99% (NASCET)33 | 659 | 21.4 | 8.6 | 12.8 | 60 | 8 | 5.8 |

| 70-99% (ECST)31** | 501 | 19.9 | 7.0 | 12.9 | 65 | 8 | 5.6 |

| 50-69% (NASCET)32 | 858 | 14.2 | 9.2 | 5.0 | 35 | 20 | 7.1 |

| 50-69% (ECST)31** | 684 | 9.7 | 11.1 | −1.4 | −14 | — | 9.8 |

| <50% (NASCET)32 | 1368 | 11.6 | 10.1 | 1.5 | 13 | 67 | 6.5 |

| <50% (ECST)31** | 1882 | 4.3 | 9.5 | −5.2 | −109 | — | 6.1 |

| Asymptomatic patients: | |||||||

| ⩾50% VA, men only45 | 444 | 7.7† | 5.6† | 2.1 | 27 | 48 | 4.4 |

| ACAS35 | 1662 | 5.0 | 3.8‡ (actual) | 1.2 | 24 | 83 | 2.6 |

| ACE43 | 2848 | 5.0§ (assumed) | 5.8 | −0.8 | — | — | 4.6 |

NASCET=North American symptomatic carotid endarterectomy trial; ECST=European carotid surgery trial; ACAS=asymptomatic carotid atherosclerosis study; ACE=aspirin and carotid endarterectomy trial; VA=Veterans Administration.

Number of patients needed to treat by endarterectomy to prevent one stroke in 2 years after the procedure, compared with medical treatment alone.

By NASCET measurement. Additional data supplied by Dr P Rothwell.

Extrapolated from results.

Assigning a perioperative risk of 2.6% based on 724 of 825 patients who actually received endarterectomy in the surgical arm of ACAS, and utilizing the 0.6% risk of stroke in each of the two years after endarterectomy. The same 1.2% risk is assumed for the ACE patients and VA patients.

No medical arm—assumed from ACAS data.

Acknowledgments

This article is adapted from Evidence Based Cardiology, edited by S Yusuf, J A Cairns, A J Camm, E L Fallen, and B J Gersh, which was published by BMJ Books in 1998.

Footnotes

This is the last of four articles

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Mortality by cause for eight regions of the world: global burden of disease study. Lancet. 1997;349:1269–1276. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07493-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnett HJM, Meldrum HE, Eliasziw M. The prevention of ischaemic stroke. In: Yusuf S, Cairns JA, Camm AJ, Fallen EL, Gersh BJ, editors. Evidence based cardiology. London: BMJ Books; 1998. pp. 992–1008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hebert PR, Gaziano JM, Chan KS, Hennekens CH. Cholesterol lowering with statin drugs, risk of stroke, and total mortality. An overview of randomized trials. JAMA. 1997;278:313–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolf PA. Epidemiology and risk factor management. In: Welch KMA, Caplan LR, Reis DJ, Siesjö BK, Weir B, editors. Primer on cerebrovascular diseases. San Diego: Academic Press; 1997. pp. 751–757. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Refsum H, Ueland PM, Nygard O, Vollset SE. Homocysteine and cardiovascular disease. Annu Rev Med. 1998;49:31–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Warfarin versus aspirin for prevention of thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation: stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation II study. Lancet. 1994;343:687–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.SPAF III Writing Committee for the Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation at low risk of stroke during treatment with aspirin. JAMA. 1998;279:1273–1277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Adjusted-dose warfarin versus low-intensity, fixed-dose warfarin plus aspirin for high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation: stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation III randomized clinical trial. Lancet. 1996;348:633–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandercock PAG, van der Belt AGM, Lindley RI, Slattery J. Antithrombotic therapy in acute ischaemic stroke: an overview of the completed randomised trials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56:17–25. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.56.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cerebral Embolism Study Group. Immediate anticoagulation of embolic stroke: a randomized trial. Stroke. 1983;14:668–676. doi: 10.1161/01.str.14.5.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaitkus PT, Berlin JA, Schwartz JS, Barnathan ES. Stroke complicating acute myocardial infarction. A meta-analysis of risk modification by anticoagulation and thrombolytic therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:2020–2024. doi: 10.1001/archinte.152.10.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohr JP the WARSS Group. Design considerations for the warfarin-antiplatelet recurrent stroke study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1995;5:156–157. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kay R, Wong KA, Yu YL, Chan YW, Tsoi TH, Ahuja AT, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1588–1593. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Stroke Trial Collaborative Group. The international stroke trial (IST): a randomized trial of aspirin, subcutaneous heparin, both, or neither among 19435 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. Lancet. 1997;349:1569–1581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Publications Committee for the Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) Investigators. Low molecular weight heparinoid, ORG 10172 (danaparoid), and outcome after acute ischemic stroke. JAMA. 1998;279:1265–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prevention in Reversible Ischemia Trial (SPIRIT) Study Group. A randomized trial of anticoagulants versus aspirin after cerebral ischemia of presumed arterial origin. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:857–865. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diener HC, Cunha L, Forbes C, Sivenius J, Smets P, Lowenthal A. European stroke prevention study 2. Dipyridamole and acetylsalicylic acid in the secondary prevention of stroke. J Neurol Sci. 1996;143:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(96)00308-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis SM, Donnan GA. Secondary prevention for stroke after CAPRIE and ESPS-2. Opinion 1. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1998;8:73–75. doi: 10.1159/000015820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dyken ML. Secondary prevention for stroke after CAPRIE and ESPS-2. Opinion 2. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1998;8:75–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Enserink M. Fraud and ethics charges hit stroke drug trial. Science. 1996;274:2004–2005. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnett HJM, Eliasziw M, Meldrum HE. Drugs and surgery in the prevention of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:238–248. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501263320408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaborative overview of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy, I: prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients. BMJ. 1994;308:81–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnett HJM, Eliasziw M, Meldrum HE. Prevention of ischemic stroke [letter] N Engl J Med. 1995;333:460. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501263320408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett CL, Weinberg BS, Rozenberg-Ben-Dror K, Yarnold PR, Kwaan HC, Green D. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura associated with ticlopidine. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:541–544. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-7-199804010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE) Lancet. 1996;348:1329–1339. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)09457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorelick PB, Hanley DF. Clopidogrel and its use in stroke patients. Stroke. 1998;29:1737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jonas S, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A. The effect of antiplatelet agents on survival free of new stroke: a meta-analysis. Stroke Clinical Updates. 1998;8:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eastcott HHG, Pickering GW, Rob CG. Reconstruction of internal carotid artery in a patient with intermittent attacks of hemiplegia. Lancet. 1954;2:994–996. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(54)90544-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barnett HJM, Plum F, Walton JN. Carotid endarterectomy—an expression of concern. Stroke. 1984;15:941–943. doi: 10.1161/01.str.15.6.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.European Carotid Surgery Trialists’ Group. Randomised trial of endarterectomy for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis: final results of the MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST) Lancet. 1998;351:1379–1387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. The benefit of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with moderate and severe stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1415–1425. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811123392002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:445–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108153250701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elmore JR, Franklin DP, Thomas DD, Youkey JR. Carotid endarterectomy: the mandate for high quality duplex. Am Vasc Surg. 1998;12:156–162. doi: 10.1007/s100169900134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. JAMA. 1995;273:1421–1428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hennerici M, Hulsbomer HB, Hefter H, Lammerts D, Rautenberg W. Natural history of asymptomatic extracranial arterial disease. Brain. 1987;110:777–791. doi: 10.1093/brain/110.3.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norris JW, Zhu CZ, Bornstein NM, Chambers BR. Vascular risks of asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Stroke. 1991;22:1485–1490. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.12.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Biller J, Feinberg WM, Castaldo JE, Whittemore AD, Harbaugh RE, Dempsey RJ, et al. Guidelines for carotid endarterectomy: a statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke. 1998;29:554–562. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.2.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barnett HJM, Eliasziw M, Meldrum HE, Taylor DW. Do the facts and figures warrant a 10-fold increase in the performance of carotid endarterectomy on asymptomatic patients? Neurology. 1996;46:603–608. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.3.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Warlow C. Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid stenosis? Lancet. 1995;345:1254–1255. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90920-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wennberg DE, Lucas FL, Birkmeyer JD, Bredenberg CE, Fisher ES. Variation in carotid endarterectomy mortality in the Medicare population. Trial hospital, volume, and patient characteristics. JAMA. 1998;279:1278–1281. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.16.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cebul RD, Snow RJ, Pine R, Hertzer NR, Norris DG. Indications, outcomes, and provider volumes for carotid endarterectomy. JAMA. 1998;279:1282–1287. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.16.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kucey DS, Bowyer B, Iron K, Austin P, Anderson G, Tu JV. Determinants of outcome following carotid endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg. 1998;28:1051–1058. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(98)70031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hobson RW, II, Weiss DG, Fields WS, Goldstone J, Moore WS, Towne JB, et al. Efficacy of carotid endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:221–227. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301283280401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chassin MR. Appropriate use of carotid endarterectomy. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1468–1471. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811123392010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]