Abstract

DNA topoisomerases (topo) I and II are molecular targets of several potent anticancer agents. Thus, inhibitors of these enzymes are potential candidates or model compounds for anticancer drugs. Leptosins (Leps) F and C, indole derivatives, were isolated from a marine fungus, Leptoshaeria sp. as cytotoxic substances. In vitro cytotoxic effects of Lep were measured using 3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide‐based viability assay. Lep F inhibited the activity of topos I and II, whereas Lep C inhibited topo I in vitro. Interestingly both of the compounds were found to be catalytic inhibitors of topo I, as evidenced by the lack of stabilization of reaction intermediate cleavable complex (CC), as camptothecin (CPT) does stabilize. Furthermore, Lep C inhibited the CC stabilization induced by CPT in vitro. In vivo band depletion analysis demonstrated that Lep C likewise appeared not to stabilize CC, and inhibited CC formation by CPT, indicating that Lep C is also a catalytic inhibitor of topo I in vivo. Cell cycle analysis of Lep C‐treated cells showed that Lep C appeared to inhibit the progress of cells from G1 to S phase. Lep C induced apoptosis in RPMI8402 cells, as revealed by the accumulation of cells in sub‐G1 phase, activation of caspase‐3 and the nucleosomal degradation of chromosomal DNA. Furthermore, Leps F and C inhibited the Akt pathway, as demonstrated by dose‐dependent and time‐dependent dephosphorylation of Akt (Ser473). Our study shows that Leps are a group of anticancer chemotherapeutic agents with single or dual catalytic inhibitory activities against topos I and II. (Cancer Sci 2005; 96: 816–824)

Abbreviations:

- CC

cleavable complex

- CPT

camptothecin

- DEVD‐AMC

acetyl‐L‐aspartyl‐L‐glutamyl‐L‐valyl‐L‐aspartyl‐7‐amino‐4‐methyl‐coumarin

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- kDNA

kinetoplast DNA

- Lep

leptosin

- MTT

3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- PBS

phosphate‐buffered saline

- PI3‐K

phosphatidylinositol‐3‐kinase

- SDS

sodium dodecylsulfate

- topo

DNA topoisomerase

- VP‐16

etoposide.

DNA topoisomerases (topos) are essential nuclear enzymes that regulate DNA topology. There are two classes of topos, classes I and II, that differ in their function and mechanism of action.( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ) Class I enzymes (topo I, EC 5.99.1.2) act by making a transient break in one DNA strand, allowing the DNA to swivel and release torsional strain, changing the linking number by steps of one.( 2 , 4 ) Class II enzymes (topo II, EC 5.99.1.3) make transient breaks in both strands of one DNA molecule, allowing the passage of another DNA duplex through the gap, changing the linking number by steps of two.( 1 , 2 , 3 ) These enzymes are crucial for cellular genetic processes such as DNA replication, transcription, recombination, and chromosome segregation at mitosis.

It has long been accepted that topos are valuable targets of cancer chemotherapeutics.( 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ) Several classes of topo inhibitors have been introduced into cancer clinics as potent anticancer drugs, including camptothecin (CPT) derivatives (e.g. irinotecan and topotecan) inhibiting topo I( 4 ) and anthracyclines (e.g. doxorubicin and mitoxantorone), epipodophyllotoxins (e.g. etoposide [VP‐16], aminoacridines (e.g. m‐AMSA) and ellipticines targeting topo II.( 4 , 5 ) These agents are active in both hematological and solid malignancies. The activity of these agents is thought to result from stabilization of the DNA/topo cleavable complex (CC), an intermediate in the catalytic cycle of the enzymes,( 2 , 5 , 6 ) resulting ultimately in apoptosis. A number of new topo inhibitors have recently been reported that do not stabilize CC. Thus, two general mechanistic classes of topo inhibitors, especially for topo II, have recently been described:( 7 ) (1) classical topo ‘poisons’ that stabilize CC and stimulate single‐ or double‐strand cleavage of DNA, such as CPT and its derivatives, indolocarbazoles for topo I, and TAS‐103( 8 ) for topos I and II; and (2) catalytic inhibitors that prevent the catalytic cycle of the enzymes at steps other than cleavage intermediates, such as dioxopiperazines, ICRF‐193 and ICRF‐154,( 7 , 9 , 10 ) aclarubicin,( 11 ) intoplicin,( 12 ) and F11782.( 13 ) Some of these compounds are dual inhibitors of topos I and II. The catalytic inhibitors of topo II, merbarone( 14 , 15 ) and dioxopiperazines,( 9 , 10 ) have been extensively studied and have been shown to inhibit the reopening of the closed clamp formed by the enzyme around DNA by inhibiting the ATPase activity of the enzyme, thus sequestering the enzyme within the cell.( 7 , 16 , 17 )

Leptosin (Lep) derivatives, Lep F and Lep C, have been isolated in our laboratory in search of cytotoxic compounds.( 18 ) In this report we describe that both of the compounds exhibited biological activities, such as the inhibition of topos and cytotoxicity against various tumor cells. Leps are strong catalytic inhibitors of topos, Lep C inhibiting topo I and Lep F inhibiting both topos I and II in vitro; Lep C targets topo I in vivo as well. These compounds have strong growth‐inhibiting and apoptosis‐inducing activities against human lymphoblastoid RPMI8402 cells and human embryonic kidney cell line 293 cells. Leps F and C inhibit the survival pathway by inactivation (i.e. dephosphorylation) of Akt/protein kinase B (EC 2.7.1.37).

Materials and Methods

Drugs and chemicals

Leps F and C (Fig. 1) were isolated from a marine fungus Lestoshaeria sp.( 18 ) CPT was provided by Yakult Honsha (Tokyo, Japan). VP‐16 was provided by Bristol‐Myers Squibb (Brea, CA, USA). ICRF‐193 was obtained from Zenyaku Kogyo (Tokyo, Japan).

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of Lep F and C.

Preparation and assay of topos

Recombinant human topo IIα was purified from a baculovirus expression system as described elsewhere.( 19 ) One unit of topo IIα was defined as the minimal amount of activity required to decatenate 0.2 µg of kinetoplast DNA (kDNA). Isolation of murine topo I from Ehrlich ascites tumor cells was carried out essentially as described previously,( 20 ) except that salt extraction of the enzyme from nuclei was with 0.35 M NaCl and the hydroxyapatite column chromatography was skipped. Topo I activity was monitored by relaxation of supercoiled plasmid DNA.( 20 , 21 ) One unit of topo I was defined as the minimal amount of activity required to relax 0.2 µg of pT2GN plasmid DNA.

Preparation of kDNA

kDNA was isolated from protozoa Crithidia fasciculata as described previously( 19 , 22 , 23 ) with some modifications. Inhibitory effect of test compounds on topo II activity was evaluated by detecting the conversion of catenated kDNA to monomer minicircles as described previously.( 19 , 24 )

Topo I‐mediated DNA cleavage assay

Topo I‐mediated cleavable complex formation assay was carried out as described elsewhere( 21 , 25 , 26 ) with some modifications. The reaction mixture (20 µL) contained 50 mM Tris‐HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 10% glycerol, 30 µg/mL bovine serum albumin, 10 units of topo I, 0.2 µg of supercoiled pT2GN plasmid DNA and 1 µL of a solution of Leps or CPT as a positive control. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 15 min at 37°C. In experiments of drug combinations, 1 µL each of a test compound and CPT were sequentially added, one before the first incubation at 37°C for 15 min, followed by a further 30‐min incubation after the addition of the other, as described in the legend to Figure 3. Then 2.5 µL of 10% sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS) and 2 µL of 20 mg/mL proteinase K were added and the reaction mixtures were digested at 37°C for 1 h. Denatured proteins and drugs were removed by extraction with 1 : 1 mixture of phenol/chloroform. Aqueous phases were taken and mixed with 4 µL of the dye/SDS stop solution and analyzed by electrophoresis on 0.6% agarose gels in the presence of 0.1 µg/mL of ethidium bromide.

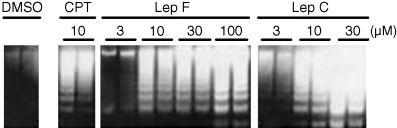

Figure 3.

Inhibition by Lep derivatives of topo I‐mediated DNA cleavage induced by CPT. Reaction mixtures containing substrate DNAs and topo I were incubated in the presence of test compounds as described in Figure 2 and under Materials and Methods. Supercoiled FI plasmid DNA was used as the substrate. After the reaction enzyme and test compounds were inactivated, the reaction products were electrophoresed on 0.6% agarose gels.

Cell culture

Human lymphoblastoid RPMI8402 cells were cultured in RPMI‐1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Human embryonic kidney cell line 293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Both of these cell cultures were kept at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

Band depletion assay

RPMI8402 cells (2 × 105) in 200 µL of RPMI‐1640 medium were prepared in a microcentrifuge tube, treated with each drug or a combination of Lep C and CPT at concentrations described in Figure 4a, and incubated for 15 min at 37°C. For a negative control, we treated cells with 2 µL of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) at the same time. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in a 10 µL of phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) spiked with two‐fold concentrations of the topo inhibitors, as described, to avoid rapid dissolution of the CC. Five µL of 4 × SDS sample buffer (250 mM Tris‐HCl, pH 6.8, 8% SDS, 2.8 mM 2‐mercaptoethanol, 40% glycerol, 0.008% bromophenol blue) was added and immediately sonicated with Sonifier 450 (Branson Ultrasonics, Danbury, CT, USA) to diminish viscosity. Samples were loaded onto 8% SDS polyacrylamide gels, electrophoresed and blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Topo I was detected by antitopo I Scl70 human serum. The membrane was stained with Ponsau S (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Drug sensitivity assay of cancer cells

RPMI8402 cells were plated in 96‐well plates at an initial density of 2000 cells/well in culture medium. One day after plating, cells were treated with various concentrations of chemotherapeutic agents and cell survival was estimated by the 3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) method.( 27 ) Three days after the drug treatment plates were centrifuged, the medium was removed and 200 µL of fresh medium containing 250 µg/mL MTT (Sigma) solution was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 4 h. The plates were centrifuged again, the supernatant was removed and precipitates were dissolved in 150 µL DMSO. The absorbance at 570 nm was measured for each well using a microplate reader (Bio‐Rad; Hercules, CA, USA). The IC50 values of drugs were calculated from the survival of cells treated for 3 days. IC50 was defined as the concentration of drug causing 50% inhibition of cell growth, as compared with the solvent control.

For drug combination analysis, pretreatment of RPMI8402 cells was performed by the addition of Lep C to the cells at various concentrations as indicated. Ten minutes later 20 nM of CPT was added to the culture and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Then the cells were harvested, washed with PBS and reseeded in 96‐well plates at a density of 2000 cells/well. Two days after reseeding, cell survival was estimated by the MTT method.

Cell cycle distribution analysis of cells treated with Lep C

RPMI8402 cells were seeded in 100 mm dishes at an initial density of 5 × 106 cells/dish in culture medium. Twelve hours after plating, the cells were treated with various concentrations of Lep C and other chemotherapeutic agents as indicated. Twenty‐four hours after the drug treatment, the cells were fixed with ice‐cold 70% ethanol for 30 min, resuspended in 10 µg/mL DNase‐free RNase A and 10 µg/mL propidium iodide, and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. After filtration with a nylon cell strainer, cell cycle distribution was monitored with an EPICS Elite (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA).

Caspase assay

Cells were lyzed in caspase lysis buffer (1 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% CHAPS and 5 mM DTT) and protein concentrations measured by Bio‐Rad reagent. Forty micrograms of proteins of cell lysate were incubated with 20 µM acetyl‐L‐aspartyl‐L‐glutamyl‐L‐valyl‐L‐aspartyl‐7‐amino‐4‐methyl‐coumarin (DEVD‐AMC; Peptide Institute, Osaka, Japan) in caspase assay buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 10% glycerol and 2 mM DTT) for 60 min at 37°C. AMC released was measured by Fluoroscan Acent FL (Thermo Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland).

DNA ladder formation analysis

Cells (3 × 106) were washed once with PBS, resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris‐HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X‐100) and centrifuged 12 000 g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was then treated with 0.2 mg/mL RNase for 1 h at 37°C, followed by treatment with 0.4 mg/mL proteinase K for 30 min at 50°C. The mixture was added with 20 µL of 5 M NaCl and 120 µL of isopropanol and stood overnight at −20°C. After centrifugation at 12 000 g at 4°C for 5 min, precipitate was dissolved in 20 µL of TE buffer (10 mM Tris‐HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA) added with 4 µL of 6 × loading dye (50% glycerol, 0.1% bromophenol blue), and electrophoresed on 2% agarose gels containing 0.1 µg/mL ethidium bromide.

Western blot analysis

Cells were solubilized with RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris‐HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% NP‐40, 10% glycerol, 2 mM EDTA).( 28 ) The cell lysates were then subjected to 10% SDS‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The proteins were transblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking, the membranes were incubated with anti‐Akt or antiphospho‐Akt (Ser473) antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA). The membrane was then incubated with an appropriate peroxidase‐conjugated secondary antibody and developed with the enhanced chemiluminescence mixture (Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Results

Lep C inhibits topo I but Lep F inhibits both topo I and II in vitro

We tested Leps for inhibition of topo I activity by monitoring the relaxation of supercoiled plasmid DNA, and for inhibition of topo II activity by kDNA decatination assay as described earlier.( 19 ) Both compounds strongly inhibited topo I activity, with IC50 values of between 3 and 10 µM for Leps C and F (Fig. 2a). However, inhibition of topo II activity was only observed with Lep F with an IC50 value of 10–30 µM. The IC50 for Lep C was more than 100 µM (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

Inhibition of DNA topoisomerase I (a) and II (b) by Leps F and C. (a) Lane 1, no enzyme (NE) added to the reaction mixture; lane 2, no test compounds (no drugs, ND) were included in the reaction; lane 3, 5 µM CPT; lane 4, 25 µM CPT; lane 5, 125 µM CPT; lane 6, 3 µM Lep F; lane 7, 10 µM Lep F; lane 8, 30 µM Lep F; lane 9, 3 µM Lep C; lane 10, 10 µM Lep C; lane 11, 30 µM Lep C. FI, supercoiled form I; FII, nicked circular form II; rFI, relaxed form I. (b) Lane 1, NE; lane 2, ND; lanes 3 and 4, 3 µM Lep F; lanes 5 and 6, 10 µM Lep F; lanes 7 and 8, 30 µM Lep F; lane 9, NE; lanes 10 and 11, ND; lane 12, 5 µM ICRF‐193; lane 13, 30 µM ICRF‐193; lanes 14 and 15, 100 µM Lep C; lanes 16 and 17, 300 µM Lep C. celDNA, cellular DNA; kDNA, kinetoplast DNA; mDNA, monomer circular DNA.

Inhibition of topo I by Leps C and F does not involve significant accumulation of DNA strand breaks

Topo inhibitors are classified according to whether they induce an accumulation of topo‐dependent DNA strand breaks as CC or not, reflecting the mechanism of inhibition. We examined whether Leps C and F inhibiting topo I induced an accumulation of CC, as described in Materials and Methods. As shown in Figure 3, CPT, a typical topo I poison, induced the accumulation of CC as indicated by an increase in nicked circular form II DNA (FII). No accumulation of FII was observed with Leps C and F up to 300 µM, indicating that Lep is not a poison but a catalytic inhibitor of topo I. It is of great interest to note that Lep C partially inhibited the CC formation by CPT, as illustrated in the two far‐right lanes in Figure 3, suggesting that Lep C suppresses the stabilization of CC induced by CPT and that Lep C interacted with topo I in steps other than those of CC formation.

Lep C targets topo I in cultured cells

To quantify DNA–topo CC formed within drug‐treated cells, the band depletion assay was employed according to previous reports,( 19 , 29 , 30 ) with some modifications. Treatment of human lymphoblastoid RPMI8402 cells with the topo I poison CPT resulted in the depletion of free enzymes detected by Western blotting (Fig. 4a), suggesting the accumulation of topo I‐mediated CC within the cells. In contrast, treatment of cells with Lep C, used as a representative Lep with higher potency of topo I inhibition, did not deplete free enzymes, indicating that Lep C is not a poison like CPT. Treatment of the cells with Lep C prior to CPT tended to restore the free topo I level, as compared with CPT alone, suggesting that Lep C competes with CPT for topo I in vivo. This competitive interaction of the two drugs in vivo appears to mimic the result obtained in in vitro study (Fig. 3). The amount of proteins loaded in each of the lanes of the gel was nearly the same, as shown in Figure 4b.

Figure 4.

Band depletion analysis of topo I in RPMI8402 human lymphoblastoma cells. (a) Cells were exposed to drugs singly or in combination, as described under Materials and Methods. Fifteen minutes after incubation, cells were collected by centrifugation and lyzed by addition of SDS‐containing lysis buffer, followed by sonication. After protein determination, immunoblotting was performed. (b) It was confirmed by staining the membrane with Ponsau S that the amounts of proteins loaded on the gel were very similar.

Lep derivatives inhibit the growth of RPMI8402 cells

The cytotoxicity of Lep C, Lep F, CPT and VP‐16 were evaluated with RPMI8402 cells. Dose–response curves were obtained and IC50 values were calculated, as shown in Figure 5. The potency of the drugs was in the following order: Lep C > CPT > Lep F > VP‐16, as depicted in the figure. RPMI8402 cells exhibited higher sensitivity to Lep derivatives than VP‐16 and were nearly as sensitive to Leps as CPT. Examination of the toxicity of Leps F and C on 39 human cancer cell lines established from various tissues from the Cancer Chemotherapy Center, Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research, Tokyo, Japan,( 31 ) revealed a similar level of cytotoxicity, with MG‐MID (mean logarithm of GI50 values, 50% growth‐inhibitory concentrations) of −7.41 and −6.8 for Lep C and Lep F, respectively.

Figure 5.

Cytotoxic activity of Lep derivatives. RPMI8402 human lymphoblastoma cells in 96‐well plates were treated with various concentrations of chemotherapeutic agents and cell survival was estimated by the MTT method. The IC50 values of drugs were calculated from the survival of cells treated for 3 days. IC50 was defined as the concentration of drug causing 50% inhibition of cell growth, as compared with the solvent control DMSO.

Leps F and C induce apoptosis in RPMI8402 cells

The sensitivity of mammalian cells against CPT cytotoxicity was shown to be the largest in S phase of the cell cycle, or rather it was S‐phase‐specific,( 32 , 33 , 34 ) so it is of great interest to investigate which cell cycle phase Leps might affect. Analysis of cell cycle distribution of cells treated with Lep C by flow cytometry showed that, compared with the solvent control (Fig. 6a), cells treated with Lep C appeared to be arrested in G1 phase, as the G1 cell population increased as the drug concentration was increased up to 10 nM (Fig. 6h,i). However, when the Lep C concentration was increased to 30 nM, the G1 population decreased and conversely the sub‐G1 fraction increased, indicating that apoptosis took place in high concentrations of the drug. In contrast, cells treated with topo I poison CPT appeared to be arrested in late S to G2/M phase (Fig. 6b–d). A similar trend of the effect of topo II poison VP‐16 arresting cells at late S to G2/M phase was observed. These experiments clearly indicate that the cellular effects of topo poisons and putative catalytic inhibitors may be different.

Figure 6.

Cell cycle distribution of cells treated with Lep C. RPMI8402 human lymphoblastoma cells were treated with various concentrations of chemotherapeutic agents for 24 h and flow cytometric analysis was performed, as described in Materials and Methods. (a) solvent control DMSO; (b) 0.02 µM CPT; (c) 0.06 µM CPT; (d) 0.18 µM CPT; (e) 0.3 µM VP‐16; (f) 1.0 µM VP‐16; (g) 3.0 µM VP‐16; (h) 3 nM Lep C; (i) 10 nM Lep C; (j) 30 nM Lep C.

We also measured caspase‐3 activation as a criterion of apoptosis in Lep‐treated RPMI8402 cells using a fluorometric assay, using DEVD‐AMC as a substrate. Caspase‐3 activity increased after 6 h of treatment with each concentration of drugs (Fig. 7). CPT induced caspase activation maximally at 1 µM. Lep C appears to be stronger than Lep F in caspase activation, as the activity increases dose‐dependently with Lep F up to 100 µM, whereas maximum activity was obtained by Lep C at 10 µM. Next, we analyzed DNA strand breaks in Lep‐treated RPMI8402 cells. DNA ladder formation indicative of nucleosome‐level degradation of DNA, and characteristic of apoptosis, was observed at 6 h after addition of the drugs (Fig. 8). These results showed that these drugs induced apoptosis, and that the inhibition of cell growth described in Figure 5 was attributed to apoptosis of cells.

Figure 7.

Activation of caspase‐3 by Lep treatment in RPMI8402 human lymphoblastoma cells. Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of Lep for 6 h. Cell lysates were incubated with the fluorogenic tetrapeptide DEVD‐AMC (20 µM) for 1 h at 37°C. The increase in caspase‐3 activity in the cell lysates was determined as described in Materials and Methods. The vertical bars represent the standard deviation value of triplicate determinations. Asterisks indicate significant differences from that of the solvent control with P‐values lower than 0.01.

Figure 8.

DNA ladder formation in RPMI8402 human lymphoblastoma cells treated with Lep derivatives. Cells were treated with the indicated doses of the drug for 6 h at 37°C. DNA was extracted and analyzed as described under Materials and Methods.

Combination of CPT and Lep C treatment showed a synergistic effect on cell growth

To evaluate the effect of a combination of Lep C and CPT on the viability of cells, RPMI8402 cells were incubated with various concentrations of Lep C for 10 min prior to the addition of 20 nM of CPT and 1 h incubation. As shown in Figure 9, in comparison with CPT treatment alone (Lep C 0), in which a 60% reduction in viability was attained, cell growth was inhibited further with increasing concentrations of Lep C up to 1000 nM, although a slight protective effect of a low concentration (1 nM) of Lep C was observed. These results indicated that a combination of CPT and Lep C showed largely an additive or supra‐additive effect on growth inhibition.

Figure 9.

The effect of combined Lep C and CPT on cell growth. RPMI8402 human lymphoblastoma cells were treated for 1 h with 20 nM of CPT and various concentrations of Lep C. Cell survival was estimated by the MTT method, as described in Materials and Methods. Asterisks indicate significant differences from that of control cells treated with CPT alone. *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001.

Lep treatment inactivates Akt by dephosphorylation in 293 cells

Among the known anti‐apoptotic pathways, the PI3‐K/Akt pathway has been shown to protect cells from pro‐apoptotic cues such as radiation and chemicals,( 35 ) and the anti‐apoptotic effect of PI3‐K is mediated primarily through activation of Akt, one of its downstream targets.( 36 ) Indeed, topotecan, a typical topo I poison, was reported to suppress the Akt signaling pathway.( 37 ) Therefore, we investigated the possibility that Leps induce apoptosis through interference with the activation of the protein kinase Akt. As the activation of Akt is mediated by phosphorylation of the kinase on Thr308 and Ser473 residues, we examined the amount of phosphorylated Akt after Lep treatment using an antiphospho‐Akt (Ser473) antibody. As shown in Figure 10a, Lep treatment decreased the amount of phospho‐Akt in human embryonic kidney 293 cells, as did the PI3‐K inhibitor LY 294002. PD 98059, an MEK inhibitor, had no effect on the phosphorylation of Akt. Along with the inactivation of Akt we examined the activation of caspase‐3 in the Lep‐treated 293 cells using the fluorogenic substrate DEVD‐AMC. Lep treatment activated caspase‐3 in 293 cells in a dose‐dependent manner (Fig. 10b). Time‐dependent inactivation of Akt was also observed: concomitant dephosphorylation of Akt and activation of caspase‐3 was shown 12 h after treatment (Fig. 11a,b). These results indicate that, in addition to topo inhibition, Lep suppressed Akt kinase activity in vivo and stimulated 293 cells to undergo apoptosis.

Figure 10.

Dose‐dependent inactivation of Akt and activation of caspase‐3 in 293 cells treated with Lep derivatives. Cells were treated with the indicated doses of Leps for 24 h. (a) The cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with antiphospho‐Akt (Ser473) and anti‐Akt antibodies. The concentrations in the figure are in µM. LY, 30 µM LY294002; PD, 45 µM PD98059. (b) Caspase‐3 activity in lysates of cells treated as described in (a) was determined as described in Materials and Methods. The vertical bars represent the standard deviation value of triplicate determinations. Asterisks indicate significant differences from that of the solvent control with P‐values lower than 0.01.

Figure 11.

Time‐dependent inactivation Akt and activation of caspase‐3 in cells treated with Lep derivatives. Human embryonic kidney cell line 293 cells were treated with 1 µM each of Leps. At the indicated time points, the cells were harvested, some of the lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis and the rest subjected to caspase assay. At time point 0, the cells were harvested before treatment of Leps. (a) Cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with an antiphospho‐Akt (Ser473) and anti‐Akt antibodies. (b) and (c) Lysates of cells prepared from Lep C (b) and Lep F (c) as in (a) were incubated with the fluorogenic tetrapeptide DEVD‐AMC (20 µM) for 1 h at 37°C. Caspase activity was determined as described in Materials and Methods. The vertical bars represent the standard deviation value of triplicate determinations. Asterisks indicate significant differences from that of the solvent control with P‐values lower than 0.01.

Discussion

Leps F and C, sulfur‐containing indole derivatives, were isolated from marine algal fungus Leptoshaeria sp. as cytotoxic substances with antitumor activity.( 18 ) Here we show that these compounds inhibit topos I and/or II: Lep F with an asymmetric structure (Fig. 1) inhibits both topo I and II, but Lep C, with an approximate symmetric structure, inhibits only topo I. The inhibitory activity of Lep C on topo I was higher than that of Lep F (Fig. 2), suggesting that Lep C fits better into the ‘left‐hand’ cleft of the topo I tertiary structure.( 38 ) These results may well be reflected by much higher cytotoxicity of Lep C than Lep F on RPMI8402 cells (Fig. 5). Drug sensitivity was similarly assessed by a panel of human cancer cell lines consisting of 39 cell lines established by the Cancer Chemotherapy Center.( 31 ) Both of these derivatives showed strong inhibitory activities, with the MG‐MID being −7.41 and −6.8 for Leps C and F, respectively. In parallel with the potency of Lep C on topo I activity, Lep C but not Lep F inhibited CC stabilization induced by CPT (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the result suggests that Lep C interacts with topo I site(s) distinct from that of CPT. Of great interest is the finding that Lep C appeared to interfere with CC stabilization induced in vivo by CPT within the nucleus (Fig. 4), implicating that Lep C also targets topo I in vivo, as it does in vitro. However, the possibility remains that Lep C interferes with CPT‐induced CC stabilization by directly interacting with CPT, or, a less likely possibility, Lep C has multiple cytotoxic targets within the cell. It is of great interest to note that compare analysis of the sensitivity fingerprints of Leps F and C with those of standard chemotherapeutics on a panel of human cancer cell lines showed that Leps have little similarity in their mode of action with known topo inhibitors of either class, poison‐type or catalytic inhibitor‐type agents.

It was clearly shown that inhibition by Leps of growth of cancer cells in vitro (Fig. 5) was due to the induction of apoptosis, as revealed by G1 arrest followed by accumulation of the sub‐G1 phase cells (Fig. 6), activation of caspase‐3 (Fig. 7) and DNA degradation (Fig. 8). In regard to cell cycle arrest, both CPT and VP‐16 clearly showed G2/M arrest (Fig. 6), whereas Lep C induced G1 block. Two mechanisms could explain the difference in the modes of action of these compounds. First, it has been shown that FOXO transcription factors are negatively regulated by the PI3‐K‐Akt signaling pathway and induce cell cycle arrest in G1.( 39 , 40 ) In this study we demonstrated that Lep C led to dephosphorylation of Akt (10, 11). So it could be considered that Lep C induces G1 arrest by activating FOXO proteins following the inhibition of Akt phosphorylation. But CPT is also known to suppress Akt phosphorylation,( 37 ) so this mechanism alone is not sufficient to explain the difference in the mode of action of these compounds. The other, more plausible mechanism relates to the difference in the mode of topo I inhibition, that is, CPT being a poison and Lep C being a catalytic inhibitor (3, 4). Topo I plays an essential role in transcription in eukaryotic cells.( 41 ) CPT has a dual action, DNA damage by stabilizing CC and inhibition of transcription, the former acting dominantly over the other, which in turn mobilizes the G2 checkpoint, resulting in G2 arrest. In contrast, Lep C is presumed to have only topo I‐inhibitory action without DNA damage and thus transcription inhibition, leading to G1 arrest. Lep C was stronger in activation of caspase‐3 than Lep F, as demonstrated by the near‐maximum activation of caspase‐3 attained by Lep C at 10 µM, whereas maximum caspase‐3 activation by Lep F was attained only at 100 µM (Fig. 7). However, analysis of DNA laddering, which is a marker for apoptotic cell death, demonstrated a similar level of potency in both compounds, that is, induction of laddering by Lep C was observed at 3–10 µM and by Lep F at 10 µM. These results suggest that apoptosis induced by Lep F involves some other signaling pathway(s), such as other executioner caspases or caspase‐independent apoptotic pathway(s) in RPMI8402 cells.

There was a considerable discrepancy in IC50 values and the effective dosage of Leps between different assays, that is, high dosage in the enzymatic assay and low dosage in the cell growth inhibition assay. Two main reasons could be considered: (1) the growth inhibition shown in Figure 5 might be caused by activating or inactivating multiple signaling pathway(s) following topo inhibition; or (2) in the enzymatic assay, a large amount of substrate DNA is needed to show up the conversion of the substrate, as shown in 3, 2, 4, whereas, in the cell‐based sensitivity assay, a small fraction of DNA conversion affects the sensitivity of cells, as also shown by other topo‐targeting drugs. As shown in 3, 4, Lep C competed with CPT for topo I in the enzymatic assay. So we investigated whether Lep C suppresses the cytotoxicity of CPT in vivo. As shown in Figure 9, and in contrast to expectation, the pre‐incubation of cells with Lep C largely enhanced the growth inhibitory effect of CPT. This might also be due to other pathway(s) leading to growth inhibition downstream of the enzymatic lesions.

Evidence has accumulated showing that various cellular damaging stimuli leading to apoptosis, such as radiation and chemical agents, inactivate the survival pathway, PI‐3K/Akt, by the dephosphorylation of Akt.( 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 ) Similarly, the CPT derivative topotecan induced apoptosis by the inactivation of PDK‐1, the direct upstream activator of Akt, followed by the dephosphorylation and proteolytic cleavage of Akt.( 36 , 46 ) Thus damage of important cellular components incurred by external stimuli appears to converge on the inactivation of the PI‐3K/Akt pathway. In line with these observations, Leps inhibiting topos within the cell were shown to lead to the dephosphorylation of Akt, but the degradation of Akt proteins was not observed by the Lep treatment (10, 11), as was reported previously.( 36 , 43 ) In 293 cells, Lep F induced a significant activation of caspase‐3 at 1–10 µM (Fig. 10b) in contrast to RPMI8402 cells, where full activation of caspase‐3 by Lep F was only observed at 100 µM (Fig. 10), suggesting that apoptotic pathways may differ in different cell types. Furthermore, the interplay between apoptotic pathways (the activation of caspases) and survival pathways (the inactivation of PI‐3K/Akt), remains elusive.

Another point of interest is the finding that Lep C induces apoptosis, most likely due to interference with the function of topo I without DNA damage, which strongly suggests that topo I is also essential for the survival and/or growth of mammalian cells in culture, as it is in the development of mouse embryos.( 47 )

In summary, the results presented here demonstrated that the cytotoxic compounds Leps F and C isolated from a marine fungus, Leptoshaeria sp., are a type of topo catalytic inhibitors in vitro as well as in vivo and that they induce apoptosis in a number of human cancer cell lines. Leps will make a valuable chemical source for anticancer drugs. Furthermore, exploitation of combining and applying this new type of topo inhibitor with conventional poison‐type inhibitors has great promise in future cancer chemotherapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out partly as an activity of the Screening Committee of New Anticancer Agents supported by a Grant‐in‐Aid No. 11177101 for Science Research on Priority Area ‘Cancer’ from The Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Japan.

References

- 1. Watt PM, Hickson ID. Structure and function of type II DNA topoisomerases. Biochem J 1994; 303: 681–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang JC. DNA topoisomerases. Annu Rev Biochem 1996; 65: 635–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang JC. Moving one DNA double helix through another by a type II DNA topoisomerase: the story of a simple molecular machine. Q Rev Biophys 1998; 31: 107–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pommier Y, Pourquier P, Fan Y, Strumberg D. Mechanism of action of eukaryotic DNA topoisomerase I and drugs targeted to the enzymes. Biochem Biophys Acta 1998; 1400: 83–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen AY, Liu LF. DNA topoisomerases: essential enzymes and lethal targets. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 1994; 34: 191–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nelson EM, Tewey KM, Liu LF. Mechanism of antitumor drug action: poisoning of mammalian DNA topoisomerase II on DNA by m‐AMSA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1984; 81: 1361–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Andoh T, Ishida R. Catalytic inhibitors of DNA topoisomerase II. Biochem Biophys Acta 1998; 1400: 155–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Utsugi T, Aoyagi K, Asao T et al. Antitumour activity of a novel quinolone derivative, TAS‐103, with inhibitory effects on topoisomerases I and II. Jpn J Cancer Res 1997; 88: 992–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ishida RT, Mild T, Narita R et al. Inhibition of intracellular topoisomerase II by antitumor bis (2,6‐dioxopiperazine) derivatives: mode of cell growth inhibition distinct from that of cleavable complex‐forming type inhibitors. Cancer Res 1991; 51: 4909–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tanabe K, Ikegami Y, Ishida R, Andoh T. Inhibition of topoisomerase II by antitumor agent bis (2,6‐dioxopiperazine) derivatives. Cancer Res 1991; 51: 4903–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jensen PB, Jensen PS, Demant EJ et al. Antagonistic effect of aclarubicin on daunorubicin‐induced cytotoxicity in human small cell lung cancer cells: relationship to DNA integrity and topoisomerase II. Cancer Res 1991; 51: 5093–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Riou JF, Fosse P, Nguyen CH et al. Intoplicine (RP 60475) and its derivatives, a new class of antitumour agents inhibiting both topoisomerase I and II activities. Cancer Res 1993; 53: 5987–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Perrin D, van Hille B, Barret JM et al. F11782, a novel non‐intercalating dual inhibitor of topoisomerases I and II with an original mechanism of action. Biochem Pharmacol 2000; 59: 807–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Drake FH, Hofmann GA, Mong SM et al. In vitro and intracellular inhibition of topoisomerase II by the antitumor agent merbarone. Cancer Res 1989; 49: 2578–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fortune JM, Osheroff N. Merbarone inhibits the catalytic activity of human topoisomerase II by blocking DNA cleavage. J Biol Chem 1998; 273: 17 643–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roca J, Ishida R, Berger JM, Andoh T, Wang JC. Antitumor bisdioxopiperazines inhibit yeast DNA topoisomerase II by trapping the enzyme in the form of a closed protein clamp. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994; 91: 1781–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morris SK, Baird CL, Linsley JE. Steady‐state and rapid kinetic analysis of topoisomerase II trapped as the closed‐clamp intermediate by ICRF‐193. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 2613–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Takahashi C, Numata A, Ito Y et al. Leptosins, antitumor metabolites of a fungus isolated from a marine alga. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1994; 1: 1859–64. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Umerura K, Mizushima T, Katayama H, Kiryu Y, Yamori T, Andoh T. Inhibition of DNA topoisomerase II and/or I by pyrazolo [1, 5‐a] indole derivatives and their growth inhibitory activities. Mol Pharmacol 2002; 62: 873–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ishii K, Hasegawa T, Fujisawa K, Andoh T. Rapid purification and characterization of DNA topoisomerase I from cultured mouse mammary carcinoma FM3A cells. J Biol Chem 1983; 258: 12 728–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yanase K, Sugimoto Y, Andoh T, Tsuruo T. Retroviral expression of a mutant (Gly‐533) human DNA topoisomerase I cDNA confers a dominant form of camptothecin resistance. Int J Cancer 1999; 81: 134–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Simpson AM, Simpson L. Isolation and characterization of kinetoplast DNA networks and minicircles from Crithidia fasciculata . J Protozool 1974; 21: 774–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shapiro TA, Klein VA, Englund PT. Isolation of kinetoplast DNA. Methods Mol Biol 1999; 94: 61–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sato S, Fukuda Y, Nakagawa R, Tsuji T, Umemura K, Andoh T. Inhibition of DNA topoisomerases by nidulalin A derivatives. Biol Pharm Bull 2000; 23: 511–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hsiang YH, Hertzberg R, Hecht S, Liu LF. Camptothecin induces protein‐linked DNA breaks via mammalian DNA topoisomerase I. J Biol Chem 1985; 260: 14 873–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Andoh T, Ishii K, Suzuki Y et al. Characterization of a mammalian mutant with a camptothecin‐resistant DNA topoisomerase I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1987; 84: 5565–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alley MC, Scudiero DA, Monks A et al. Feasibility of drug screening with panels of human tumor cell lines using a microculture tetrazolium assay. Cancer Res 1988; 48: 589–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang HG, Takayama S, Rapp UR, Reed JC. Bcl‐2 interacting protein, BAG‐1, binds to and activate the kinase Raf‐1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996; 93: 7063–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hsiang YH, Liu LF. Identification of mammalian DNA topoisomerase I as an intracellular target of the anticancer drug camptothecin. Cancer Res 1988; 48: 1722–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kaufmann SH, Svingen PA. Immunoblot analysis and band depletion assays. Methods Mol Biol 1999; 94: 253–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yamori T, Matsunaga A, Sato S et al. Potent antitumor activity of MS‐247, a novel DNA minor groove binder, evaluated by an in vitro and in vivo human cancer cell line panel. Cancer Res 1999; 59: 4042–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li LH, Fraser TJ, Olin EJ, Bhuyan BK. Action of camptothecin on mammalian cells in culture. Cancer Res 1972; 32: 2643–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Horwitz SB, Horwitz MS. Effects of camptothecin on the breakage and repair of DNA during the cell cycle. Cancer Res 1973; 33: 2834–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu LF. Biochemistry of camptothecin. In: Milan P, Pinado H, eds. Camptothecins: New Antitumor Agents. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 1995; 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yao R, Cooper GM. Requirement for phosphatidylinositol‐3 kinase in the prevention of apoptosis by nerve growth factor. Science 1995; 267: 2003–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Franke TF, Kaplan DR, Cantley LC. PI3K: downstream AKTion blocks apoptosis. Cell 1997; 88: 435–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nakashio A, Fujita N, Rokudai S, Sato S, Tsuruo T. Prevention of phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase‐Akt survival signaling pathway during topotecan‐induced apoptosis. Cancer Res 2000; 60: 5303–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Redinbo MR, Stewart L, Kuhn P, Champoux JJ, Hol WGJ. Crystal structures of human topoisomerase I in covalent and noncovalent complexes with DNA. Science 1998; 279: 1504–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang HS, Cao EH, Qin JF. Homocysteine induces cell cycle G1 arrest in endothelial cells through the PI3K/Akt/FOXO signaling pathway. Pharmacology 2005; 74: 57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yusuf I, Zhu X, Kharas MG, Chen J, Fruman DA. Optimal B‐cell proliferation requires phosphoinositide 3‐kinase‐dependent inactivation of FOXO transcription factors. Blood 2004; 104: 784–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Drolet M, Wu HY, Liu LF. Roles of DNA topoisomerases in transcription. In: Liu LF, ed. DNA Topoisomerases: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Massachusetts: Academic Press, 1994; 135–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fujiwara H, Yamakuni T, Ueno M et al. IC101 induces apoptosis by Akt dephosphorylation via an inhibition of heat shock protein 90‐ATP binding activity accompanied by preventing the interaction with Akt in L1210 cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2004; 310: 1288–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kulp SK, Yang YT, Hung CC et al. 3‐Phosphoinoditide‐dependent protein kinase‐1/Akt signaling represents a major cyclooxygenase‐2‐independent target for celecoxib in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 1444–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lee TK, Man K, Ho JW et al. FTY720 induces apoptosis of human hepatoma cell lines through PI3‐K‐mediated Akt dephosphorylation. Carcinogenesis 2004; 25: 2397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Suzuki T, Kobayashi M, Isatsu K et al. Mechanisms involved in apoptosis of human macrophages induced by lipopolysaccharide from actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in the presence of cycloheximide. Infect Immune 2004; 72: 1856–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rokudai S, Fujita N, Hashimoto Y, Tsuruo T. Cleavage and inactivation of antiapoptotic Akt/PKB by caspases during apoptosis. J Cell Physiol 2000; 182: 290–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Morham SG, Kluckman KD, Voulomanos N, Smithies O. Targeted disruption of the mouse topoisomerase I gene by camptothecin selection. Mol Cell Biol 1996; 16: 6804–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]