Abstract

The management of relapsed or refractory B‐cell non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma (B‐NHL) remains challenging. We investigated the efficacy and safety of salvage chemoimmunotherapy (CHASER) in patients with relapsed or refractory B‐NHL who had radiographically measurable disease and adequate major organ function. The CHASER treatment consisted of: rituximab 375 mg/m2, day 1; cyclophosphamide 1200 mg/m2, day 3; cytarabine 2 g/m2, days 4 and 5; etoposide 100 mg/m2, days 3–5; and dexamethasone 40 mg, days 3–5. The treatment was repeated every 3 weeks up to a total of four courses in the absence of disease progression. Thirty‐two patients were enrolled and received a median of four courses of treatment (range 1–4 courses) per patient. Twenty patients (63%) were previously treated with rituximab‐containing regimens. The median age was 54 years (range 28–67 years). The treatment was generally well tolerated, with major toxicities being grade 4 neutropenia (n = 32), thrombocytopenia requiring transfusion (n = 28), and grade 3 transaminase elevation (n = 2). Overall response rates in the entire group, and in patients with indolent (n = 17) and aggressive (n = 15) diseases were 84%, 100% and 67%, respectively. Responses were observed similarly in patients with (n = 20) and without (n = 12) previous rituximab exposure (85% and 83%, respectively). Stem cell harvest was successful in 19 of 22 patients. The median time to treatment failure for the entire group was 24.5 months. This promising result of high activity and favorable toxicity profile warrants further investigation in large‐scale multicenter trials. (Cancer Sci 2008; 99: 179–184)

Abbreviations:

- ANC

absolute neutrophil count

- B‐NHL

B‐cell non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma

- CHASE

cyclophosphamide, high‐dose cytarabine, dexamethasone, and etoposide

- CHASER

cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, etoposide, dexamethasone, and rituximab

- CHOP

cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone

- CI

confidence interval

- CR

complete response

- CRu

complete response unconfirmed

- DHAP

dexamethasone, high‐dose cytarabine, and cisplatin

- ESHA

etoposide, methylprednisone, and high‐dose cytarabine

- ESHAP

ESHA plus cisplatin

- NHL

non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma

- ORR

overall response rate

- OS

overall survival

- R‐CHOP

rituximab with CHOP

- R‐DHAP

rituximab with DHAP

- R‐ESHAP

rituximab with ESHAP

- SCT

stem cell transplantation

- TTF

time to treatment failure

Although a certain proportion of patients with NHL have an excellent prognosis after initial treatment, many patients with NHL develop relapsed or refractory disease. Management of such conditions remains challenging, and salvage regimens to better control the disease are needed. We previously reported the safety and efficacy of combination salvage chemotherapy called CHASE( 1 ) that consists of cyclophosphamide, high‐dose cytarabine, steroid (dexamethasone), and etoposide. CR was observed in 10 of 14 patients (71%) with relapsed or refractory NHL. This regimen was well tolerated, and was associated with no renal toxicities, in contrast to other commonly used cisplatin containing salvage regimens such as DHAP( 2 ) and ESHAP( 3 ) which are associated with irreversible increase in serum creatinine in 4–8% of patients. Although the original report of CHASE included only a small number of patients, CHASE has been widely used as a salvage therapy in Japan given the significant efficacy and tolerability.

Anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody, rituximab, has recently revolutionized the management of B‐NHL. Rituximab can contribute to improved disease control and survival when added to initial standard combination chemotherapy( 4 , 5 ) and the use of rituximab in the salvage setting has also shown significant activity with minimal toxicity.( 6 , 7 ) However, it remains to be shown whether rituximab containing salvage chemotherapy is still as effective in patients with previous exposure to rituximab. Based on the encouraging clinical data of CHASE chemotherapy as well as rituximab in salvage settings, we carried out an open‐label, phase II clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of combination chemoimmunotherapy using CHASE and rituximab (CHASER) in patients with relapsed or refractory B‐NHL.

Materials and Methods

Patient selection. The protocol for the current study was approved by the institutional review board of Aichi Cancer Center Hospital (Aichi, Japan). To be eligible for the study, patients were required to have histologically confirmed relapsed or refractory NHL, with CD20 positivity on tumor cells by immunohistochemistry and bidimensionally measurable disease by computed tomography scan. Patients were also required to: be aged between 15 and 69 years; have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 0–2; have received ≥1 previous treatment regimens; and have adequate bone marrow function (ANC ≥1.5 × 109/L, and platelet count ≥100 × 109/L), liver function (total bilirubin level ≤2 mg/dL, and aspartate aminotransaminase and alanine aminotransaminase levels ≤2.5 times the upper limit of normal), and kidney function (serum creatinine level ≤2 mg/dL).

Patients were ineligible if they had lymphoma involvement in the central nervous system; had serum hepatitis B surface antigen; had serum HIV antibody; had uncontrolled intercurrent illnesses such as active infection, cardiac diseases, active second malignancy, or psychiatric disease. Those who were pregnant or lactating were ineligible. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before study entry, consistent with national and local requirements. All patients gave written informed consent indicating that they were aware of the investigational nature of the study, in keeping with the policies of Aichi Cancer Center Hospital.

Treatment schedule. The regimen consisted of rituximab 375 mg/m2 intravenously on day 1; cyclophosphamide 1200 mg/m2 intravenously over 3 h on day 3; cytarabine 2 g/m2 intravenously over 3 h on days 4 and 5; etoposide 100 mg/m2 intravenously on days 3–5; dexamethasone 40 mg intravenously on days 3–5 and G‐CSF (filgrastim, lenograstim, or nartograstim at the primary physician's choice) 2 µg/kg subcutaneously from day 6 till neutrophil recovery. The treatment was to be repeated every 3 weeks up to a total of four courses unless there is disease progression, persistent grade 3/4 toxicity, or delayed recovery of neutrophils (<1.0 × 109/L) or platelets (<75 × 109/L). Peripheral blood stem cell harvest was carried out after the second and/or third cycle if the patient was a suitable candidate for future SCT, targeting a total CD34 count of 2.0 × 106/kg body weight or higher.

Supportive care during chemotherapy. Patients were to be premedicated with antihistamine and antipyretics prior to rituximab infusion. Effective antiemetics such as 5‐HT3 receptor antagonist were given intravenously prior to chemotherapy and as needed. To prevent hemorrhagic cystitis from cyclophosphamide, at least 3000 mL of hydration with bicarbonate‐containing fluid was required on day 1. Mesna was not given in this study.

Response and toxicity assessments. To assess response, patients were required to be re‐evaluated with a thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic computed tomography scan every two cycles. The International Workshop Response Criteria for NHL were used for evaluating responses( 8 ) except that clearance of tumor cells from bone marrow needed to be confirmed by morphologic as well as flow cytometric assessment in patients who had bone marrow involvement on study entry.

Toxic effects were originally graded according to the National Cancer Center Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (version 2.0), and regarded after data collection and analyses based on version 3.0. Patients were evaluated daily with a complete history and physical examination. The laboratory assessment was carried out at least twice weekly to monitor organ toxicity and electrolyte abnormalities.

Dose modifications. If a patient's ANC was >1.0 × 109/L and platelet count was between 75 × 109/L and 100 × 109/L (condition A) at the due date for initiation of the next treatment, doses of cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, and etoposide were reduced by 25% for the next cycle. If a patient's ANC was <1.0 × 109/L or platelet count was <75 × 109/L, the treatment needed to be postponed until condition A was achieved, and the doses were reduced as in condition A. If this improvement did not occur in a week, that is, at four weeks after the previous cycle, the patient was removed from the study. If persistent arrhythmia, cardiac ischemia, pericarditis, or grade 3/4 heart failure were observed, the patient was removed from the study. If grade 3/4 hepatotoxicity was present at initiation of the next cycle, the treatment was postponed till the toxicity was grade 2 or less. If grade 3 hepatotoxicity was persistent at 4 weeks after initiation of previous treatment, the patient was removed from the study. If serum creatinine was between 1.6 and 1.9 mg/dL, or increased from baseline by 0.5–1.2 mg/dL (condition B), the dose of cytarabine was reduced by 50% (1 g/m2) because of the risk of severe neurological toxicity. The doses of other agents were not changed, as they were not expected to significantly increase the risks of severe non‐hematologic toxicities from this degree of mild renal impairment. If serum creatinine was ≥2 mg/dL, or increased from baseline by 1.3 mg/dL (condition C), the treatment needed to be postponed till condition B was achieved, and the dose of cytarabine was reduced by 50% when initiating treatment. If condition C was persistent at 4 weeks after previous treatment, the patient was removed from the study. If grade 4 non‐hematologic toxicity or performance status of 4 without improvement during the treatment course was observed, the patient was removed from the study.

Statistical methods. The primary endpoint of this study was an ORR and the secondary endpoints were TTF, OS, successful stem cell mobilization (in patients planned for SCT, as described earlier), and toxicities. The study used a two‐stage design, where 11 patients were recruited in the first stage and if eight or more responses were observed, an additional 21 patients were recruited for the second stage. The two‐stage design was based on alpha = 0.05, power = 90%, undesirable response rate = 60%, and desirable response rate = 85%. Statistical analysis for patients’ characteristics, response rates, and adverse events was descriptive. Analysis on response rate, TTF, and OS was carried out on an intent‐to‐treat basis, using the Kaplan–Meier method. The TTF was calculated from the time of registration to the time of disease progression, change of treatment, or disease‐ or treatment‐related death. Those who eventually underwent SCT were censored for TTF at the initiation of conditioning treatment. OS duration was calculated from the time of registration to the time of death of any cause.

Results

Patient characteristics. Thirty‐two eligible patients were enrolled between November 2002 and November 2006. All received at least one course of CHASER chemotherapy. Baseline patient and disease characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age was 54 years (range 28–67 years), and most (n = 30, 94%) of the patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1. Seventeen had indolent NHL (all follicular grade 1 or 2), and 15 had aggressive NHL (11 diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma, two mantle cell lymphoma, one large cell transformation of marginal zone lymphoma, and one large cell transformation of follicular lymphoma grade 2). The majority of patients (n = 22, 69%) had stage III or IV disease.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients ( n = 32) with relapsed or refractory B‐cell non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma who participated in this study

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 32 | 100 |

| Median age in years (range) | 54 (28–67) | |

| Male/female | 17/15 | 53/47 |

| Histology | ||

| Indolent | 17 | 53 |

| Follicular grade 1/2 | 17 | 53 |

| Aggressive | 15 | 47 |

| DLBCL | 11 | 34 |

| MCL | 2 | 6 |

| Large cell transformation of indolent lymphoma | 2 | 6 |

| ECOG performance status at entry | ||

| 0/1 | 30 | 94 |

| 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Stage at entry | ||

| 1 | 5 | 16 |

| 2 | 5 | 16 |

| 3 | 5 | 16 |

| 4 | 17 | 53 |

| LDH at entry | ||

| Normal | 18 | 56 |

| High | 14 | 44 |

| No. of sites of extranodal involvement | ||

| 0 | 13 | 41 |

| 1 | 14 | 44 |

| 2 or more | 5 | 16 |

| IPI score at study entry | ||

| 1 | 12 | 38 |

| 2 | 10 | 31 |

| 3 | 10 | 31 |

| No. of prior treatment regimens | ||

| 1 | 22 | 69 |

| 2 | 4 | 16 |

| 3 | 3 | 6 |

| 4 or more | 3 | 9 |

| Prior platinum‐containing therapy | 1 | 3 |

| Prior rituximab‐containing therapy | 20 | 63 |

| Prior radiation therapy | 4 | 13 |

| Prior radioimmunotherapy (90Yttrium‐ibritumomab) | 1 | 3 |

| Prior autologous stem cell transplant | 2 | 6 |

| Refractory to last chemotherapy | 10 | 31 |

| Relapsed disease | ||

| Previous remission duration ≤1 year | 8 | 25 |

| Previous remission duration >1 year | 14 | 44 |

DLBCL, diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IPI, International Prognostic Index; LDH, Iactate dehydrogenase; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma.

All patients were previously treated with CHOP‐based chemotherapy at the time of initial diagnoses, and the majority of patients (n = 22, 69%) entered the current study for the first salvage treatment. Twenty patients (63%) were previously treated with rituximab‐containing therapy. Four patients (13%) previously received radiation therapy for local disease control. Overall, 10 patients (31%) had diseases refractory to last treatment, and the remaining 22 patients (69%) had relapsed diseases.

Toxicity. A total of 113 courses of CHASER were given, with a median of four courses (range 1–4 courses) per patient. All patients were assessable for adverse events associated with CHASER (Table 2). There was no treatment‐related death or toxicity leading to discontinuation of the treatment. All experienced grade 4 neutropenia, but the duration of neutropenia (<500) was short (median 4 days per course, range 0–8). The median time to neutrophil nadir was 13 days (range 10–19 days). Twenty‐five patients (78%) experienced neutropenic fever and all but one were managed successfully with a short course of broad‐spectrum antibiotics. One patient experienced a prolonged febrile episode and required 10‐day intravenous antibiotic treatment. The majority of patients (n = 28, 88%) required at least one platelet transfusion during the therapy, with a median of one transfusion per course (range 1–3 transfusions). The median time to platelet nadir was 14 days (range 10–19 days). Most common non‐hematologic toxicity was gastrointestinal (nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, and elevated liver enzymes). Transient elevation of serum transaminases (grade 3) was observed in two patients. One patient experienced an episode of syncope (grade 3), which was most likely to be a vasovagal syncope and the association with the study drugs was unclear. There were no grade 4 or other grade 3 toxicities observed.

Table 2.

Toxicity observed in patients with relapsed or refractory B‐cell non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma during salvage chemoimmunotherapy incorporating cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, etoposide, dexamethasone, and rituximab ( n = 32)

| Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematologic | ||||

| Neutropenia (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 32 (100) |

| Thrombocytopenia (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (13) | 28 (88) |

| Febrile neutropenia (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 25 (78) | 0 (0) |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||

| Nausea/vomiting (%) | 9 (28) | 4 (13) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Diarrhea (%) | 6 (19) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Elevated liver enzymes (%) | 14 (44) | 4 (13) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) |

| Neurological | ||||

| Peripheral neuropathy (%) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Syncope (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Pain (%) | 1 (3) | 4 (13) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Edema (%) | 4 (13) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Three patients (9%) required delay in the treatment schedule due to slow recovery of the platelet count. One experienced a non‐life‐threatening but prolonged febrile neutropenia after the third cycle as described earlier, and doses of cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, and etoposide for the fourth course were reduced by 25%. One patient who experienced hyperglycemia, which was difficult to control with insulin after the third cycle, received only 12 mg of dexamethasone for the fourth cycle at the discretion of the responsible physician.

Response. The objective response of all 32 evaluable patients is summarized in Table 3. ORR was 84% (95% CI [67–95%]), including CR or CRu in 24 patients (75%[57–89%]), and partial response in three patients (9%). The ORR and CR rates in indolent lymphoma were 100% (84–100%; 17 of 17) and 94% (71–99%; 16 of 17), respectively, and those in aggressive lymphoma were 67% (38–88%; 10 of 15) and 53% (27–79%; 8 of 15), respectively. Response was observed both in patients who previously received rituximab (17 of 20, 85%) and those who did not (10 of 12, 83%) (P = 0.37). In patients with aggressive B‐NHL with (n = 8) or without (n = 7) prior rituximab exposure, ORR was 63% and 71%, respectively (P = 0.39), and CR rate was 57% and 50%, respectively (P = 0.38). The CR rate was higher in patients with longer than 1 year of response duration after last treatment (93%, 13 of 14) than in patients with 1 year or shorter of response duration or refractory disease after last treatment (61%, 11 of 18) (P = 0.047). Other factors such as International Prognostic Index (IPI) score at study entry, response to the first treatment were not significantly associated with overall or complete response to CHASER (data not shown). Two patients who had previously undergone autologous SCT also experienced responses (CR and partial response, respectively). Three patients achieved only stable disease and proceeded to different salvage regimens after two, two and four cycles, respectively. Two patients had rapidly progressive disease after one and two cycles, respectively, and eventually received different salvage regimens.

Table 3.

Responses observed in patients with relapsed or refractory B‐cell non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma (B‐NHL) after treatment with salvage chemoimmunotherapy incorporating cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, etoposide, dexamethasone, and rituximab

| Type of B‐NHL | Prior treatment | Total no. | CR or Cru | Overall response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indolent B‐NHL | All | n = 17 | n = 16 | n = 17 |

| 94% (71–99%) | 100% (84–100%) | |||

| Previous rituximab | n = 12 | n = 11 | n = 12 | |

| 92% (62–99%) | 100% (78–100%) | |||

| Rituximab‐naive | n = 5 | n = 5 | n = 5 | |

| 100% (55–100%) | 100% (55–100%) | |||

| Aggressive B‐NHL | All | n = 15 | n = 8 | n = 10 |

| 53% (27–79%) | 67% (38–88%) | |||

| Previous rituximab | n = 8 | n = 4 | n = 5 | |

| 50% (16–84%) | 63% (24–91%) | |||

| Rituximab‐naive | n = 7 | n = 4 | n = 5 | |

| 57% (18–90%) | 71% (29–96%) | |||

| Total | All | n = 32 | n = 24 | n = 27 |

| 75% (57–89%) | 84% (67–95%) | |||

| Previous rituximab | n = 20 | n = 15 | n = 17 | |

| 75% (51–91%) | 85% (62–97%) | |||

| Rituximab‐naive | n = 12 | n = 9 | n = 10 | |

| 75% (43–95%) | 83% (52–98%) |

Ranges in parentheses indicate 95% confidence interval. CR, complete response; CRu, complete response unconfirmed.

Stem cell collection and SCT. Although not required to enter the study, all patients aged 65 years (n = 30) were offered at study entry an option of peripheral blood stem cell harvesting, to be carried out after the second (and third, if necessary) course of CHASER for future SCT. Out of 30 patients, stem cell collection was not attempted in eight patients: three patients with follicular lymphoma declined this option; two patients had undergone autologous SCT prior to CHASER; and three patients had poor control of disease during CHASER (two progressive disease and one stable disease). As a result, stem cell collection was attempted in 22 patients. Three had insufficient mobilization of CD34 positive cells in peripheral blood; one of these patients had had three prior regimens including one cladribine‐containing regimen. The remaining 19 patients successfully completed stem cell collection, with a median CD34 count of 4.0 × 106/kg body weight (range 1.9–23.4 × 106) by a median of two rounds of apheresis (range 1–3 rounds). All collected stem cell sources were free of malignant B cells, determined by flow cytometric analyses. In six patients with follicular lymphoma with MBR/JH rearrangement detected by seminested polymerase chain reaction (using primer sets LJH‐P, TGAGGAGACGGTGACC and MBR‐P, CCAAGTCATGTGCATTTCCACGTC for the first step, and VLJH‐P, GTGACCAGGGTNCCTTGGCCCCAG and MBR‐P for the second step). Negativity of tumor cell contamination in the stem cell sources was confirmed by the same method (data not shown). Two of 19 patients with aggressive NHL had suboptimal response (stable disease) on imaging studies after CHASER, thus proceeded to other salvage regimens. One patient who had adequate stem cell collection refused to undergo SCT. As a result, a total of 16 patients (50%) underwent autologous SCT as an immediate next treatment after CHASER treatment. One patient who had undergone autologous SCT prior to CHASER underwent allogeneic SCT as an immediate next treatment after CHASER.

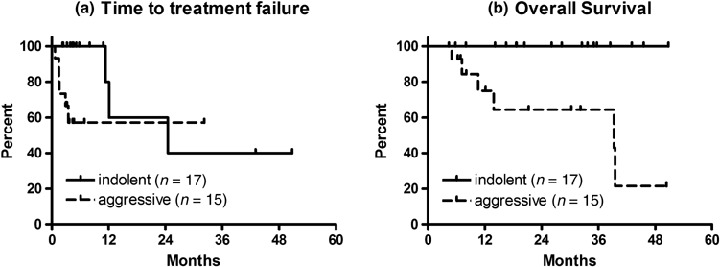

TTF and OS. The Kaplan–Meier estimates of TTF and OS are shown in Fig. 1. The median TTF and OS durations for the entire group were 24.5 months and not reached, respectively. The median TTF in patients with indolent and aggressive lymphoma was 24.5 months and not reached, respectively. The median OS duration in patients with indolent and aggressive lymphoma was not reached and 39.3 months, respectively. Neither TTF nor OS duration was significantly different by IPI score at study entry, response duration after last chemotherapy (refractory or ≤1 year vs >1 year), previous rituximab exposure, or response to the first treatment (log–rank test, data not shown).

Figure 1.

Overall survival (OS) and time to treatment failure (TTF) in patients with relapsed or refractory B‐cell non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma undergoing salvage chemoimmunotherapy incorporating cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, etoposide, dexamethasone, and rituximab. Solid lines indicate survival curves of patients with indolent lymphoma (n = 17). Dashed lines indicate those of patients with aggressive lymphoma (n = 15). (a) The median TTF in patients with indolent and aggressive lymphoma was 24.5 months and not reached, respectively. Those who had stem cell transplant were censored for TTF at the initiation of conditioning regimen. (b) The median OS duration in patients with indolent and aggressive lymphoma was not reached and 39.3 months, respectively.

Discussion

Patients with relapsed or refractory NHL have limited options and poor prognosis. Even in patients who might be candidates for autologous SCT, it is critical to reduce the tumor size with an effective salvage regimen prior to SCT. For those who are not candidates for transplant, a treatment regimen to induce a durable response is the sole key for long‐term survival. The present study showed the significant activity of the new combination salvage regimen CHASER in patients with relapsed or refractory B‐NHL who may or may not have undergone prior rituximab‐containing treatment such as R‐CHOP.

Although rituximab has been studied in salvage settings as an additional drug to commonly used combination chemotherapy, such as ESHAP( 7 ) DHAP( 9 , 10 ), and ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin and etoposide)( 6 , 10 ), currently available data are from studies recruiting mostly rituximab‐naive patients (Table 4). Therefore, it remains to be shown whether R‐ICE (rituximab with ICE) or R‐DHAP is still as effective in patients who were previously treated with a rituximab‐containing regimen.( 10 ) It is noteworthy in our study that CHASER produced high CR rates in relapsed or refractory B‐NHL after rituximab‐containing chemotherapy, and that the activity seems comparable to those of other platinum‐containing regimens in patients with aggressive B‐NHL (Table 4). Randomized trials would be needed to further compare the efficacy of CHASER with other regimens. Also, careful long‐term follow‐up is needed to assess the potential late effect of rituximab, such as delayed neutropenia as has recently been recognized.( 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 )

Table 4.

Comparison of CHASER, R‐DHAP, R‐ESHAP and R‐ICE in relapsed or refractory aggressive B‐cell non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma (doses are per course)

| CHASER | R‐DHAP( 9 ) | R‐ESHAP( 7 ) | R‐ICE( 6 ) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rituximab | 375 mg/m2 × 1 | 375 mg/m2 × 1 | 375 mg/m2 weekly × 8 | 375 mg/m2 × 1 |

| Cytarabine | 2 g/m2 × 2 | 2 g/m2 × 2 | 2 g/m2 × 1 | – |

| Etoposide | 100 mg/m2 × 3 | – | 40 mg/m2 × 4 | 100 mg/m2 × 3 |

| Steroid | Dexamethasone 40 mg × 3 | Dexamethasone 40 mg × 4 | Methylprednisolone 500 mg × 5 | – |

| Platinum agent | – | Cisplatin 25 mg/m2 × 4 | Cisplatin 25 mg/m2 × 4 | Carboplatin AUC 5 × 1 |

| Non‐platinum alkylator | Cyclophosphamide 1200 mg/m2 × 1 | – | – | Ifosfamide 5 g/m2 × 1 |

| No. of patients | 15 | 53 | 26 | 36 |

| Prior rituximab exposure (%) | 53 | 4 | 19 † | 0 |

| CR rate % (95% CI) | 53 (27–79) | 32 (20–46) | 46 (27–65) | 53 (36–69) |

| OR rate % (95% CI) | 67 (38–88) | 62 (48–75) | 92 (82–100) | 78 (61–90) |

L. Hicks et al., 2007, personal communication; –, not included in treatment; AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; OR, overall survival.

Both CHASER and R‐ESHAP contain high‐dose cytarabine, etoposide, steroid, and rituximab in common. In the original study of ESHAP, Velasquez et al. initially compared ESHA with ESHAP( 3 ), revealing that the addition of cisplatin significantly improved the response rate (33%vs 75% at initial phase of the study, but the response rate of ESHAP at the end of the study was 64%), despite only moderate activity of single agent cisplatin against NHL (response rate 26%( 15 )). Further addition of rituximab to ESHAP seems even more active, and in a phase II study of R‐ESHAP in patients with aggressive B‐NHL (n = 26, 21 were rituximab‐naive), a response rate of 92% (95%[CI 84–100%]) including a CR rate of 46% (95%[27–65%]) was observed. CHASER contains 1200 mg/m2 of cyclophosphamide instead of cisplatin, producing comparable response rates to R‐ESHAP. Virtually all patients with relapsed or refractory B‐NHL were exposed to cyclophosphamide at 750 mg/m2 as a part of CHOP therapy, however, a higher dose of cyclophosphamide seems to play a significant role in overcoming resistance in this setting. Furthermore, one major benefit of using cyclophosphamide instead of cisplatin is absence of renal toxicity.

One important aspect of salvage regimens for relapsed or refractory NHL is their stem cell mobilizing effect. In our study, 19 of 22 attempts at stem cell collection were successful, but it should be noted that one of three who experienced poor stem cell mobilization had been heavily pretreated. Furthermore, addition of rituximab to the CHASE regimen might add an in vivo purging effect and allow tumor‐free stem cell collection. Further studies are necessary to determine whether in vivo purged autologous SCT will improve outcomes compared to non‐purged SCT.

In conclusion, CHASER showed favorable tolerability, significant antitumor activity, and stem cell mobilizing effects in patients with relapsed or refractory B‐NHL with or without prior rituximab‐containing treatment such as R‐CHOP. This promising result warrants the further investigation of CHASER in large‐scale multicenter trials and comparison to other salvage regimens.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Health and Labour Science Grants for Clinical Cancer Research from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. We thank Dr Eisei Kondo for his laboratory work.

References

- 1. Ogura M, Kagami Y, Taji H et al . Pilot phase I/II study of new salvage therapy (CHASE) for refractory or relapsed malignant lymphoma. Int J Hematol 2003; 77: 503–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Velasquez WS, Cabanillas F, Salvador P et al . Effective salvage therapy for lymphoma with cisplatin in combination with high‐dose Ara‐C and dexamethasone (DHAP). Blood 1988; 71: 117–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Velasquez WS, McLaughlin P, Tucker S et al . ESHAP – an effective chemotherapy regimen in refractory and relapsing lymphoma: a 4‐year follow‐up study. J Clin Oncol 1994; 12: 1169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J et al . CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large‐B‐cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 235–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pfreundschuh M, Trumper L, Osterborg A et al . CHOP‐like chemotherapy plus rituximab versus CHOP‐like chemotherapy alone in young patients with good‐prognosis diffuse large‐B‐cell lymphoma: a randomised controlled trial by the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol 2006; 7: 379–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kewalramani T, Zelenetz AD, Nimer SD et al . Rituximab and ICE as second‐line therapy before autologous stem cell transplantation for relapsed or primary refractory diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. Blood 2004; 103: 3684–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hicks L, Buckstein R, Mangel J et al . Rituximab increases response to ESHAP in relapsed, refractory, and transformed aggressive B‐cell lymphoma (Abstract). Blood 2006; 108: 3067. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B et al . Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non‐Hodgkin's lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mey UJ, Olivieri A, Orlopp KS et al . DHAP in combination with rituximab vs DHAP alone as salvage treatment for patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma: a matched‐pair analysis. Leuk Lymphoma 2006; 47: 2558–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hagberg H, Gisselbrecht C: CORAL Study Group . Randomised phase III study of R‐ICE versus R‐DHAP in relapsed patients with CD20 diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma (DLBCL) followed by high‐dose therapy and a second randomisation to maintenance treatment with rituximab or not: an update of the CORAL study. Ann Oncol 2006; 17 (Suppl 4): iv31–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chaiwatanatorn K, Lee N, Grigg A, Filshie R, Firkin F. Delayed‐onset neutropenia associated with rituximab therapy. Br J Haematol 2003; 121: 913–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lemieux B, Tartas S, Traulle C et al . Rituximab‐related late‐onset neutropenia after autologous stem cell transplantation for aggressive non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant 2004; 33: 921–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nitta E, Izutsu K, Sato T et al . A high incidence of late‐onset neutropenia following rituximab‐containing chemotherapy as a primary treatment of CD20‐positive B‐cell lymphoma: a single‐institution study. Ann Oncol 2007; 18: 364–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Voog E, Morschhauser F, Solal‐Celigny P. Neutropenia in patients treated with rituximab. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 2691–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cavalli F, Jungi WF, Nissen NI, Pajak TF, Coleman M, Holland JF. Phase II trial of cis‐dichlorodiammineplatinum (II) in advanced malignant lymphoma: a study of the cancer and acute leukemia group B. Cancer 1981; 48: 1927–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]