Abstract

In the past decade, more than 20 therapeutic antibodies have been approved for clinical use and many others are now at the clinical and preclinical stage of development. Fragment crystallizable (Fc)‐dependent antibody functions, such as antibody‐dependent cell‐mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), complement‐dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), and a long half‐life, have been suggested as important clinical mechanisms of therapeutic antibodies. These functions are primarily triggered through direct interaction of the Fc domain with its corresponding receptors: FcγRIIIa for ADCC, C1q for CDC, and neonatal Fc receptor for prolongation of the clearance rate. However, current antibody therapy still faces the critical issues of insufficient efficacy and the high cost of the therapeutic agents. A possible solution to these issues could be to engineer antibody molecules to enhance their antitumor activity, leading to improved therapeutic outcomes and reduced doses. Here, we review advanced Fc engineering approaches for the enhancement of effector functions, some of which are now ready for evaluation of their effectiveness in clinical trials. (Cancer Sci 2009; 100: 1566–1572)

Current status of therapeutic antibodies

Since the mid 1990s, monoclonal antibodies have demonstrated enormous potential as new classes of drugs and more than 20 therapeutic antibodies have been approved. These approved therapeutic antibodies are now commonly used in the clinical management of a variety of diseases and have been recognized as particularly effective tools in the treatment of certain malignancies.( 1 , 2 ) The most successful examples include antibodies raised against CD20, Her2/neu (also known as ErbB2), epidermal growth factor receptor, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which demonstrate improved overall survival of patients and time to disease progression in a variety of malignancies, such as breast, colon, and hematological cancers.( 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 )

Compared to conventional small‐molecule drugs, therapeutic advantages of antibody drugs are attributed to their intrinsic characteristics as an immunological protein molecule originally developed in the body: highly selective specificity and capability to induce fragment crystallizable (Fc)‐related functions. Although the broad reactivity of small molecule inhibitors for multiple tyrosine kinases sometimes seems to associate with their therapeutic benefits,( 8 , 9 , 10 ) high specificity of antibodies results in the low frequency of off‐target effects and their relatively predictable toxicities. The other advantage, Fc‐related function which is especially unique to antibody therapeutics, includes long serum half‐lives (typically ~2 weeks in humans) and effector functions that utilize intrinsic immunological mechanisms to destroy target cells. In turn, due to their large molecular sizes (~150 kDa), therapeutic antibodies have some limitations in their delivery: inability to target intracellular molecules, less efficient tissue penetration, and poor bioavailability when given orally.

The initial technological breakthrough that has accelerated the development of therapeutic antibodies was the reduction of the immunogenicity of mouse‐derived antibodies by establishing mouse/human chimeric antibodies,( 11 ) humanized antibodies,( 12 ) and fully human antibodies.( 13 , 14 ) However, despite the several successful examples of marketed antibody drugs with reduced immunogenicity, there still remains an urgent need to improve the effectiveness of antibody therapies. In studies with rituximab, the first approved anti‐CD20 chimeric monoclonal antibody (mAb) for cancer treatment, only half of the patients showed clinical response (either partial or complete) and the median duration of response to single agents was only 12 months.( 15 , 16 ) In a phase III study with trastuzumab, an anti‐Her2/neu mAb for the treatment of metastatic breast cancers overexpressing Her2, median overall survival improved by only 5 months as compared with standard chemotherapy (25.1 vs 20.3 months).( 17 ) Another example, bevacizumab, an anti‐VEGF mAb for the treatment of late‐stage colon cancer, extended median overall survival by only 30% as compared with standard chemotherapy (20.3 vs 15.6 months).( 18 )

Another issue in current antibody therapeutics is its economically intolerable cost, mainly due to the use of mammalian expression systems to produce the agents and the large‐scale purification processes that are required. The continuous high‐dose administration (generally, 2–8 mg/kg per administration) of a therapeutic antibody, which is often required to maintain an effective serum concentration to induce a clinical response,( 19 , 20 ) not only limits the current clinical applications/regimens because of the dose‐related side effects but also narrows their potential fields of indication.

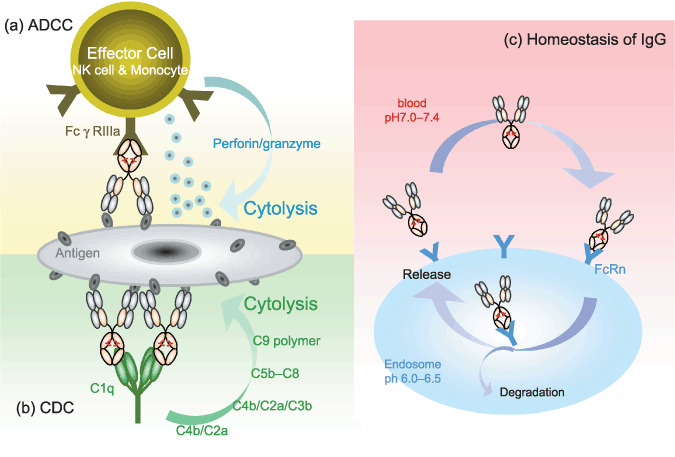

Engineering and enhancing antibody functions have therefore been investigated as a means of circumventing these issues. Numerous studies, including in vitro, in vivo, and clinical studies, have shed light on the effector functions of antibodies as important mechanisms of action of therapeutic antibodies in addition to their binding affinity and specificity for targets, in particular antibody‐dependent cell‐mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), complement‐dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), and a long half‐life/clearance rate (Fig. 1). Each of these effector functions is primarily triggered through direct interaction of the Fc domain of the antibody with its corresponding ligands: ADCC through interaction with the Fc gamma receptor IIIa (FcγRIIIa), CDC through interaction with the series of soluble blood proteins that constitute the antibody‐dependent complement activation pathway (e.g. C1q, C3, and C4), and serum persistence through interaction with the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn).

Figure 1.

The mechanism of effector functions, antibody‐dependent cell‐mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), complement‐dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), and homeostasis of immunogloblin, derived from fragment crystallizable (Fc) domain. (a) Mechanism of ADCC in which antigen‐specific antibodies direct immue effector cells. This mechanism relies on the engagement of FcγRIs (FcγRIIIa in humans) and the recruitment of immune effector cells in an Fc‐dependent manner, leading to the destruction of the target cells via exocytosis of the cytolytic granule complex perforin/granzyme. (b) Mechanism of CDC. CDC can be triggered by binding of C1q to the Fc domain of antibody molecules bound on the target cells. Then following pathway can be activated and lead to cell cytolysis. (c) Mechanism of homeostasis of IgG through the binding of Fc domain to Fc receptor (FcRn). The binding is strictly pH‐dependent; IgG can bind FcRn in endosomes under mildly acidic conditions (pH 6.0–6.5) and can be released from the cell surface under slightly basic conditions (pH 7.0–7.4).

In this review, we will focus on advanced Fc engineering approaches, which enhance effector functions by altering amino acids in the Fc domain or by modifying Fc‐linked glycosylation. One such approach is represented by the innovative platform established by our group: enhancement of ADCC activity achieved by fucose depletion from the Fc‐linked oligosaccharide (de‐fucosylated antibody) and enhancement of CDC activity achieved by IgG1 and IgG3 isotype shuffling. Antibodies produced by the use of these technologies have demonstrated enhanced efficacy in a series of preclinical experiments. A discussion of clinical perspectives will then follow, based on the preliminary results of clinical trials with de‐fucosylated antibodies as next‐generation therapeutic antibodies.

Basic structure of therapeutic antibodies

Although there are several classes/subclasses of immunoglobulins in humans, current therapeutic antibodies are mostly of the IgG1 isotype because of their long serum half‐life and their capacity for strong effector functions as compared to those of other classes/subclasses.( 21 )

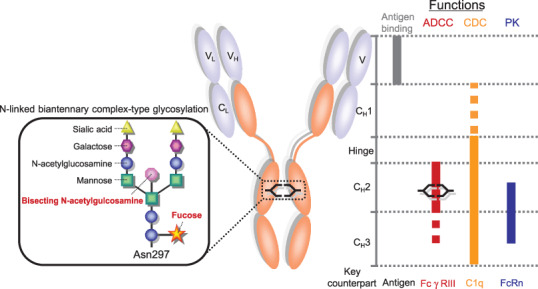

The basic structure of human IgG1 is a heterodimer of ~150 kDa, consisting of two light and two heavy chains in covalent and non‐covalent association, divided into three independent protein moieties: two Fab domains and one Fc domain, which are connected through a flexible polypeptide called the hinge region (Fig. 2). The N‐terminus of each light and heavy chain is linked to the variable regions (VL and VH), which determine its unique binding affinity/specificity for antigen molecules. The rest of the antibody molecule, known as the constant region, consists of a CL domain, constituting the light chain, and a CH domain, divided into CH1, hinge, CH2, and CH3 regions, constituting the heavy chain. Whereas the variable region determines binding to targets, it is the Fc domain which binds to its counterparts that can trigger effector functions, including three structurally homologous cellular Fc receptor types (FcγRI, FcγRII, and FcγRIII), the C1q component of the complement, and the FcRn.( 22 , 23 )

Figure 2.

General IgG structure and critical region to enhance each functions. Human IgG is composed of two identical heavy chains and light chains via covalent and non‐covalent association. Each heavy chain is composed of heavy chain variable region (VH), CH1, Hinge, CH2, and CH3. Each light chain is composed of light chain variable region (VL) and CL. General human IgG has two N‐linked oligosaccharides at ASN297 in the CH2 domain. The general structure of N‐linked oligosaccharide is complex‐type as described in box. N‐linked oligosaccharide is characterized by a mannosyl‐chitobiose core comprised of N‐acetylglucosamine and mannose with or without bisecting N‐acetylglucosamine, core fucose, galactose, and sialic acid. Left panel indicates critical regions to improve each function by current robust enhancing approaches.

In addition, human IgG1 bears two N‐linked biantennary complex‐type oligosaccharides covalently attached at the conserved asparagine 297 (Asn297), which is in the CH2 domain. These oligosaccharides are composed of a mannosyl‐chitobiose core structure in the presence or absence of a core fucose, a bisecting N‐acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), and terminal galactose and sialic acid. This structure gives rise to heterogeneity with a mixture of 30 or more glycoforms.( 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 )

Furthermore, the presence of oligosaccharides and its glycoforms is critical for induced effector functions through their influence on the major interaction of the Fc domain with its counterparts.( 21 , 28 ) Crystal structure analysis shows that Fc‐linked oligosaccharides influence the conformation of the Fc domain via multiple non‐covalent interactions with the CH2 domains.( 29 , 30 , 31 )

Antibody‐dependent cell‐mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC)‐enhancing technologies. ADCC is a cytolytic effector mechanism of antibodies in which antigen‐specific antibodies direct immune effector cells, primarily natural killer (NK) cells, in the process of innate immunity by killing antigen‐expressing cancer cells. This mechanism relies on the engagement of FcγRs (FcγRIIIa in humans) and recruitment of immune effector cells in an Fc‐dependent manner, leading to the destruction of target cells by exocytosis of the cytolytic granule complex perforin/granzyme from NK cells.( 32 )

A number of preclinical studies have suggested that ADCC is a major mechanism of action of antitumor antibodies, such as rituximab,( 33 ) trastuzumab,( 34 , 35 ) and alemtuzumab, an anti‐CD52 mAb.( 36 , 37 ) Furthermore, the importance of ADCC has also been recognized in clinical settings, as evidenced by significant correlation between FcγRIIIa functional polymorphisms and clinical outcomes of multiple therapeutic antibodies. The response rates to rituximab in patients with follicular non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma were better in a cohort carrying the higher‐affinity FcγRIIIa variant (Val158‐homozygous genotype) than in patients carrying the lower‐affinity FcγRIIIa allotype (Phe158).( 38 , 39 ) Similar correlations were also seen for trastuzumab,( 40 ) cetuximab,( 41 ) and infliximab.( 42 ) Thus, enhancing ADCC activity could become a standard approach in the development of the next generation of more potent therapeutic antibodies.

Amino acid modification in the Fc domain. Enhancing ADCC activity by modifying the amino acid sequence of the Fc domain has been extensively studied, mainly through the random mutational analysis of human IgG1 Fc,( 43 ) sometimes assisted by a computational rationale together with high‐throughput protein expression systems. Shields et al.( 43 ) have reported Fc‐domain variants with up to three mutations (S298A, E333A, and K334A, numbered according to the EU index( 44 )) with improved binding to FcγRIIIa and enhanced capacity for ADCC, which were screened from a comprehensive set of amino acid mutations that covers the accessible surface of the human IgG1 Fc.

Stavenhagen et al.( 45 ) have screened a number of comprehensive Fc mutants using a unique yeast display system and found variants with up to five mutations (F243L, R292P, Y300L, V305I, and P396L) showing ~10‐fold binding affinity to FcγRIIIa and improved ADCC activity.

More recently, computational design algorithms based on structural information regarding the Fc/FcγR interface have been used to design an IgG1 Fc variant (S239D/A330L/I332E) with an ~100‐fold improvement in binding affinity to FcγRIIIa, which has remarkably enhanced ADCC activity in vitro and in cynomolgus monkeys.( 46 )

Oligosaccharide modification of the Fc domain. The other established approach for enhancing ADCC activity is the modification of the oligosaccharide structure in the Fc domain. An IgG molecule contains two N‐linked oligosaccharides at the conserved asparagine 297 (N297) in the CH2 domain. The general structure of the N‐linked oligosaccharide on IgG is complex‐type, characterized by a mannosyl‐chitobiose core (Man3GlcNAc2‐Asn) with variations in the presence/absence of bisecting GlcNAc, the innermost L‐fucose (Fuc), the non‐reducing terminal Gal, and sialic acid (Fig. 2). Glycosylation itself and variations in glycoforms are known to affect various biological funcions of IgG.( 28 , 47 )

Several groups have focused on the bisection of GlcNAc, a β1,4‐GlcNAc residue attached to a core β‐mannose residue, which can affect the biological activity, especially ADCC, of therapeutic antibodies.( 48 ) An anti‐neuroblastoma IgG1( 49 ) and an anti‐CD20 IgG1( 50 ) antibody, each having oligosaccharides fully modified by bisecting GlcNAc, produced using a N‐acetylglucosaminyltransferase III (GnTIII)( 51 )‐transfected Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell line, showed more than 10‐fold enhancement of ADCC activity as compared with their non‐bisected parent IgG1s.

Other groups including ours have focused on the fucose residue for its outstanding effect on ADCC. For the first time, our group revealed that among the sugar components, including bisected GlcNAc, fucose has the most critical role in enhancing ADCC activity, and that its elimination markedly increases ADCC activity by improving FcγRIIIa binding.( 52 , 53 ) Antibodies with highly de‐fucosylated oligosaccharides were shown to exhibit ~100‐fold higher ADCC activity than their fully fucosylated counterparts in various antigen/antibody systems( 54 ) and to possess enhanced in vivo antitumor activity.( 55 )

Enhancement of ADCC activity by the removal of fucose is a rather universal phenomenon, which is not only seen for human IgG1 but also for various antibody species, such as other IgG subclasses,( 56 ) ligand/Fc fusion proteins,( 57 ) and single‐chain Fv/Fc fusion proteins.( 58 )

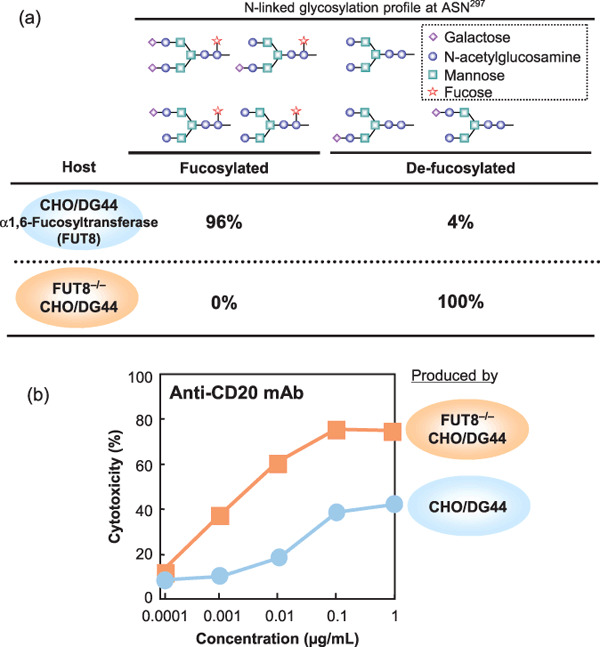

Production of de‐fucosylated therapeutic antibodies. Despite the potential benefits of de‐fucosylated antibodies, the currently marketed therapeutic antibodies are composed of a highly fucosylated (> 90%) glycoform because of the characteristics of the host cell lines. Therefore, to develop a therapeutic antibody which exhibits the greatest ADCC activity, it is essential to establish a robust process for the manufacture of therapeutic antibodies that fully lack fucosylation.

Most approved therapeutic antibody production processes employ rodent mammalian cells as host cell lines for their commercial production such as CHO cell lines and the mouse myeloma cell lines NS0 and SP2/0 because of their high productivity and the well‐established manufacturing processes.( 59 ) However, these mammalian cell lines are not suitable for the production of completely de‐fucosylated antibodies as they retain a high level of intrinsic α‐1,6‐fucosyltransferase (FUT8) enzyme activity, which is responsible for the core fucosylation of N‐linked oligosaccharides.( 60 )

Therefore, decreasing or eliminating FUT8 activity in commonly used host cell lines would be the most effective way to achieve stable and efficient production of de‐fucosylated antibodies. Given that even a trace of contaminating fucosylated antibody will hinder ADCC activity by antigen sharing (as discussed later), the ideal host cells for the production of de‐fucosylated antibodies would have to show complete depletion of FUT8. With this aim, we established FUT8 knockout CHO cell lines by gene targeting using a homologous recombination technique( 53 ) (Fig. 3). Except for the complete depletion of FUT8 expression, the properties of the established FUT8 knockout CHO cells were unaltered from those of the parent cells in terms of morphology, growth kinetics, and productivity. These cells stably produce completely de‐fucosylated antibodies with fixed quality and consistently enhanced ADCC activity.( 53 , 61 )

Figure 3.

Comparison between conventional CHO/DG44 and α‐1,6‐fucosyltransferase (FUT8)‐KO CHO/DG44. (a) Oligosaccharide profile of chimeric anti‐CD20 IgG prepared from rituxan, commercially produced in CHO/DG44 cells and FUT8−/–‐produced IgG1. Fucosylated oligosaccharides were not observed in FUT8‐/–‐produced IgG1. (b) In vitro antibody‐dependent cell‐mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) activity of rituxan, produced in CHO/DG44 cells and FUT8−/–‐produced IgG1.

Preclinical evaluation of de‐fucosylated antibodies. In vitro and in vivo evaluations of de‐fucosylated antibodies have suggested that their enhanced ADCC activity will lead to the improvement of the activities of therapeutic antibodies as compared to those of conventional antibodies. For example, they showed potent ADCC activity at low antigen densities, whereas conventional fucosylated antibodies could not induce detectable ADCC activity.( 54 ) Furthermore, the use of de‐fucosylated antibodies might overcome the problem of individual heterogeneity in FcγRIIIa functional polymorphism: a de‐fucosylated variant of rituximab has achieved a high level of ADCC activity even in NK cells harboring FcγRIIIa‐158Phe, known as the low‐affinity allotype.( 62 ) Furthermore, while conventional therapeutic antibodies compete with serum IgG (present at >10 mg/mL) for binding to FcgRIIIa and thereby exhibit significantly hindered ADCC activity in the presence of human serum, ADCC mediated by de‐fucosylated antibodies is not significantly affected in the same experimental setting because of the augmented affinity for FcgRIII.

Interestingly, the enhanced ADCC activity of de‐fucosylated antibodies can be inhibited by adding fucosylated antibodies of the same antigen specificity by sharing the antigen molecules on the surface of target cells.( 63 ) Since ADCC activity is quite sensitive to reduction in the number of antigen molecules, addition of fucosylated anti‐CD20 antibody results in a significant reduction in the ADCC activity of de‐fucosylated antibodies.( 63 ) This supports the importance of a stable method for the production of completely de‐fucosylated antibodies as discussed above.

These results indicate that de‐fucosylated antibodies with enhanced ADCC activity are promising candidates for the next‐generation antibody‐based therapeutics.

In terms of immunogenicity, de‐fucosylated IgG1 is a natural component of human serum IgG; for example, rituximab contains a small amount of the de‐fucosylated form.( 25 , 26 ) Hence, de‐fucosylated therapeutic antibodies are expected to be less immunogenic or non‐immunogenic as compared to those produced by other artificial or modified approaches.

Clinical trials of ADCC‐enhancing antibodies. After proving their promising biological activities in the laboratory, a number of engineered antibodies with improved ADCC activity are now ready for the evaluation of their therapeutic potential in clinical trials. The race to develop next‐generation anti‐CD20 antibodies is highly competitive; the ADCC‐enhancing antibodies ocrelizumab( 64 ) and AME‐133( 65 ) both possess engineered Fc‐bearing amino acid mutations, and GA101( 66 ) has engineered oligosaccharides in its Fc domain. These antibodies have the capacity to mediate improved ADCC activity as compared with rituximab, and results of their clinical trials for treating CD20‐positive lymphomas will be available in the near future.

De‐fucosylated antibodies have begun to demonstrate clinical activity and an acceptable safety profile, which supports their continuing development in an effort to demonstrate that they represent an approach that will be useful in the production of next‐generation therapeutic antibodies.

CC chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4) is a chemokine receptor present in Th2 subset of helper T‐cells and has also been suggested as a novel molecular target for antibody therapy of various T‐cell malignancies.( 67 , 68 )

A phase I study of KW‐0761, a de‐fucosylated humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody against CCR4 has been conducted in relapsed patients with CCR4‐positive adult T‐cell leukemia‐lymphoma and peripheral T‐cell lymphoma. For the 16 patients who received KW‐0761 with doses ranging from 0.01 to 1.0 mg/kg, the overall response rate was 31%.( 69 )

A notable highlight of the preliminary clinical trials of the de‐fucosylated anti‐CCR4 antibody is the dosages, which have induced investigator‐assessed clinical responses. This de‐fucosylated anti‐CCR4 antibody has shown clinical responses at doses markedly lower than the standard dose range of currently marketed therapeutic antibodies (of the order 1.0 mg/kg or even higher).( 17 , 70 ) Hence, it could be expected that the platform of de‐fucosylated antibodies will provide great benefits as demonstrated in a number of preclinical studies, and will lead to reductions in the doses administered.

Another de‐fucosylated antibody has also indicated the benefits of this type of antibody in a clinical trial. MEDI‐563, a de‐fucosylated humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody against interleukin‐5 receptor (IL‐5R) currently being developed by MedImmune, has shown an acceptable safety profile and potent biological activity in a phase I study for mild asthma. Interim results for the first cohort (single intravenous dose at 0.03 mg/kg) showed that peripheral blood eosinophils expressing IL‐5R were undetectable for a minimum of 58 days with no signs of severe adverse effects at a far lower dose than those use for most approved therapeutic antibodies.( 71 )

Complement‐dependent cytotoxicity (CDC). CDC is a cytolytic cascade known as the ‘classical pathway’ of the complement system, and is mediated by a series of complement proteins (C1–C9) that are abundantly present in the serum. It is triggered by binding of C1q to the Fc domain of antibody molecules bound on the cell surface. A number of anti‐tumor antibodies, e.g. antibodies raised against CD20, CD52, Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA)‐class II, Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA), glycolipid antigens, etc., have been known to induce CDC, and rituximab does attack tumor cells via a complement‐dependent mechanism in mouse models.( 72 ) In the clinic, rapid consumption of complement component followed by rituximab infusion has been observed in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients, suggesting that complements are actually utilized in patients.( 73 ) Furthermore, one of the most convincing examples of the therapeutic importance of this activity is the good clinical responses seen in a phase I study of ofatumumab,( 74 ) a second‐generation anti‐CD20 antibody, which is capable of inducing much more potent CDC activity than rituximab due to its distinct epitope.( 75 ) In patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in whom rituximab monotherapy typically shows no or only ~30% response at a maximum, an overall response of 50% was seen after ofatumumab treatment, and the safety profile was acceptable.( 76 )

However, tumor cells can evade from antibody attack by various biological resistance mechanisms. For CDC‐resistant mechanisms, expression of complement regulatory proteins (CRPs: CD35, CD46, CD55 and CD59), which inhibit protease cascade of complements on cell surface, significantly decrease CDC activity of rituximab against follicular non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma and Burkitt's lymphoma cell lines.( 77 ) CRPs have also been suggested as a possible resistance factors in antibody therapies, as exemplified by the up‐regulation of CD59 in returning tumor cells after rituximab therapy( 78 ) or higher expression of CD55 in bulky lymph node tumors in patients with non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma.( 79 ) These facts suggest that efficacy of current therapeutic antibodies is potentially hindered by CRPs; thus, there is an urgent need for novel antibody therapeutics with improved CDC activity.

In an effort to improve the complement‐mediated therapeutic activity of antibodies, several antibody mutants have been successfully generated, which enhance CDC activity by facilitating the binding of the Fc domain to C1q. As a result of amino acid modification in the CH2 domain( 80 ) or hinge region,( 81 ) antibodies with the designed constant region have exhibited improvement in C1q binding and CDC activity.

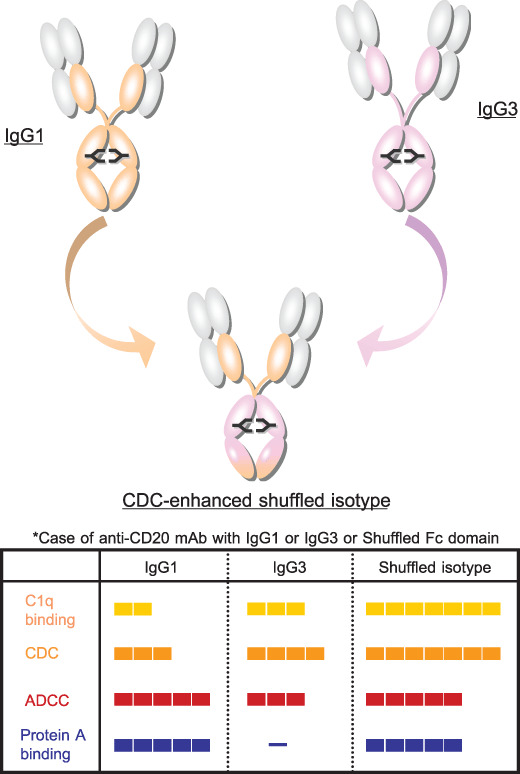

Another approach for enhancing CDC activity is engineering of the heavy chain by shuffling IgG1 and IgG3 sequences within a heavy chain constant region, as recently reported by our group( 82 ) (Fig. 4). Somewhat surprisingly, several variant heavy constant regions screened from a set of IgG1/IgG3 mixed sequences showed unexpectedly strong C1q binding and CDC activity that exceeded the levels observed for either parental IgG1 or IgG3. The degree of enhancement of CDC activity in an anti‐CD20 system obtained by using the IgG1/IgG3 mixed constant regions reached several tens‐fold in vitro when compared with wild‐type rituximab. Moreover, its enhanced cytotoxicity was also confirmed in a cynomolgus monkey B‐cell depletion model.( 82 ) This method may be unique in that it probably generates no immunogenic epitope, whereas the artificial mutational approaches illustrated above potentially produce non‐self peptides within their sequences. Another important feature of this variant constant region is that it retains its binding affinity to FcγRIIIa and ADCC activity as the same level as those of parental IgG1 both in fucose‐negative and positive settings. Namely, the ADCC‐enhancing modification by fucose removal and the CDC‐enhancing modification by using the variant constant region can be combined successfully without affecting each other, to create a powerful (and probably still non‐immunogenic) antibody scaffold with dual enhanced effector functions.( 82 )

Figure 4.

The structure of complement‐dependent cytotoxicity (CDC)‐enhanced shuffled isotype and comparison of principal properties among IgG1, IgG3, and shuffled isotype antibody. CDC‐enhanced isotype can be generated by shuffling between IgG1 and IgG3 in the fragment crystallizable (Fc) domain. A part of human IgG1 heavy chain is converted into the corresponding part of human IgG3 (upper figure). Anti‐CD20 mAbs that have IgG1 or IgG3 or shuffled Fc isotypes are compared in binding affinity for human C1q protein, CDC, and ADCC activity with Raji, a CD20‐positive cancer‐cell line, and binding capacity of protein A in the lower panel.

Techniques for improving the pharmacokinetics of therapeutic antibodies. Another direction in the improvement of the therapeutic efficiency of antibodies might be the further prolongation of their long in vivo half‐lives (typically, ~2 weeks in humans). With this aim, there have been extensive studies attempting to introduce mutations in the Fc domain that render antibodies capable of more strongly binding the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn). This receptor is expressed in a variety of endothelial cells and mediates IgG homeostasis through the binding of IgG to FcRn. This binding is strictly pH‐dependent; IgG can bind FcRn in endosomes under mildly acidic conditions (pH 6.0–6.5) and can be released from the cell surface under slightly basic conditions (pH 7.0–7.4).( 83 ) Using random mutagenesis and a phage display screening method, selected mouse Fc mutants were produced that showed improved binding to FcRn and had longer serum half‐lives than mouse IgG in a mouse model.( 84 ) Moreover, molecular modeling and/or a comprehensive Fc mutagenesis approach was used to identify residues in the Fc domain near the FcRn binding site.( 43 , 79 , 80 ) Several mutants with increased pH‐dependent binding affinity to FcRn were identified and one of these mutants prolonged plasma half‐life almost 2‐fold in rhesus monkeys as compared with the parent IgG.( 85 , 86 ) Such an approach may also be feasible for the production of next‐generation therapeutic antibodies and may lead to a reduction in the cost of treatment, for example by improving efficacy, reducing dose and frequency of dosing, or increasing the interval between doses.

Perspectives

Over the past decade, tremendous progress has been made in the treatment of certain hematologic malignancies and solid tumors with therapeutic antibodies. Unlike many small‐molecule drugs, these successes were mainly derived from the unique characteristics of antibody molecules, such as their target specificity, long serum half‐life, and the mechanisms by which they recruited the immune system. However, current antibody therapeutics still has limitations that need to be overcome. After detailed analysis of factors causing these limitations, many now believe that enhancing effector functions is one of the most promising approaches for improving clinical efficacy and resolving the present issues.

As discussed in this review, several candidates for the next‐generation therapeutic antibodies produced by established Fc engineering approaches have demonstrated marked improvement of efficacy in vitro,( 45 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 76 ) ex vivo,( 63 ) and in animals.( 46 , 55 , 76 , 79 ) However, it is still not known whether the improvement of effector functions observed in preclinical studies will be accurately reflected in patients due to the lack of appropriate animal models. Mainly, because of differences in the immune system, it is difficult to evaluate and predict the clinical benefit or safety characteristics from results obtained using these models. In addition, the choice of target functions/approaches to be enhanced should be carefully determined based on biological and mechanistic understanding of the target tumors and antigens, and so on.

Importantly, as introduced in this review, studies on several next‐generation therapeutic antibodies have provided clues to these unanswered questions in early clinical trials. In particular, preliminary clinical results with ADCC‐enhanced de‐fucosylated therapeutic antibodies indicate that this approach may provide patients with improved clinical efficacy at much lower dose administration while maintaining an acceptable safety profile. Clinical studies with these therapeutic antibodies are under way and further results will answer the remaining questions. Moreover, technological advances and/or a combination of technologies that may lead to enhanced multiple antitumor mechanisms are being evaluated, and it is hoped that this will lead to the development of much more potent therapeutic antibodies.

References

- 1. Pavlou AK, Belsey MJ. The therapeutic antibodies market to 2008. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2005; 59: 389–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reichert JM, Rosensweig CJ, Faden LB, Dewitz MC. Monoclonal antibody successes in the clinic. Nature Biotechnol 2005; 23: 1073–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oldham RK, Dillman RO. Monoclonal antibodies in cancer therapy: 25 years of progress. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 1774–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cheson BD. Monoclonal antibody therapy for B‐Cell Non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Eng J Med 2008; 359: 613–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hudis CA. Trastuzumab – Mechanism of action and use in clinical practice. N Eng J Med 2007; 357: 39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peeters M, Price T, Van Laethem JL. Anti‐epidermal growth factor receptor monotherapy in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: Where are we today? Oncologist 2009; 14: 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marty M, Pivot X. The potential of anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor therapy in metastatic breast cancer: clinical experience with anti‐angiogenic agents, focusing on bevacizumab. Eur J Cancer 2008; 44: 912–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Imai K, Takaoka A. Comparing antibody and small‐molecule therapies for cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2006; 6: 714–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wilhelm S, Carter C, Lynch M et al . Discovery and development of sorafenib: a multikinase inhibitor for treating cancer. Nat Rev Drug Disc 2006; 5: 835–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Faivre S, Demetri G, Sargent W, Raymond E. Molecular basis for sunitinib efficacy and future clinical development. Nat Rev Drug Disc 2007; 6: 734–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morrison SL, Johnson MJ, Herzenberg LA, Oi VT. Chimeric human antibody molecules: mouse antigen‐binding domains with human constant region domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1984; 81: 6851–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jones PT, Dear PH, Foote J, Neuberger MS, Winter G. Replacing the complementarity‐determining regions in a human antibody with those from a mouse. Nature 1986; 321: 522–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tomizuka K, Yoshida H, Uejima H et al . Functional expression and germline atransmission of a human chromosome fragment in chimaeric mice. Nat Genet 1997; 16: 133–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mendez MJ, Green LL, Corvalan JRF et al . Functional transplant of megabase human immunoglobulin loci recapitulates human antibody response in mice. Nat Genet 1997; 15: 146–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McLaughlin P, Grillo‐López AJ, Link BK et al . Rituximab chimeric anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy for relapsed indolent lymphoma: half of patients respond to a four‐dose treatment program. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 2825–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davis TA, Grillo‐López AJ, White CA et al . Rituximab anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy in non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma: safety and efficacy of re‐treatment. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18: 3135–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Slamon DJ, Leyland‐Jones B, Shak S et al . Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 783–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W et al . Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 2335–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berinstein NL, Grillo‐López AJ, White CA et al . Association of serum rituximab (IDEC‐C2B8) concentration and anti‐tumor response in the treatment of recurrent low‐grade or follicular non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma. Ann Oncol 1998; 9: 995–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goldenberg MM. Trastuzumab, a recombinant DNA‐derived humanized monoclonal antibody, a novel agent for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Clin Ther 1999; 21: 309–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Clark MR. IgG effector mechanisms. Chem Immunol 1997; 65: 88–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jefferis R, Lund J, Pound JD. IgG‐Fc‐mediated effector functions: molecular definition of interaction sites for effector ligands and the role of glycosylation. Immunol Rev 1998; 163: 59–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jefferis R, Lund J. Interaction sites on human IgG‐Fc for FcgammaR: current models. Immunol Lett 2002; 82: 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rademacher TW, Parekh RB, Dwek RA. Glycobiology. Annu Rev Biochem 1988; 57: 785–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mizuochi T, Taniguchi T, Shimizu A, Kobata A. Structural and numerical variations of the carbohydrate moiety of immunoglobulin G. J Immunol 1982; 129: 2016–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harada H, Kamei M, Tokumoto Y et al . Systematic fractionation of oligosaccharides of human immunoglobulin G by serial affinity chromatography on immobilized lectin columns. Anal Biochem 1987; 164: 374–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jefferis R. Glycosylation of human IgG antibodies: relevance to therapeutic applications. BioPharm 2002; 14: 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wright A, Morrison SL. Effect of glycosylation on antibody functions: implications for genetic engineering. Trends Biotechnol 1997; 15: 26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huber R, Deisenhofer J, Colman PM, Matsushima M, Palm W. Crystallographic structure studies of an IgG molecule and an Fc fragment. Nature 1976; 264: 415–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Radaev S, Motyka S, Fridman WH, Sautes‐Fridman C, Sun PD. The structure of a human type III Fcgamma receptor in complex with Fc. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 16469–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Harris LJ, Skaletsky E, McPherson A. Crystallographic structure of an intact IgG1 monoclonal antibody. J Mol Biol 1998; 275: 861–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Carter P. Improving the efficacy of antibody‐based cancer therapies. Nat Rev Cancer 2001; 1: 118–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reff ME, Carner K, Chambers KS et al . Depletion of B cells in vivo by a chimeric mouse human monoclonal antibody to CD20. Blood 1994; 83: 435–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cooley S, Burns LJ, Repka T, Miller JS. Natural killer cell cytotoxicity of breast cancer targets is enhanced by two distinct mechanisms of antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity against LFA‐3 and HER2/neu. Exp Hematol 1999; 27: 1533–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sliwkowski MX, Lofgren JA, Lewis GD, Hotaling TE, Fendly BM, Fox JA. Nonclinical studies addressing the mechanism of action of trastuzumab (Herceptin). Semin Oncol 1999; 26: 60–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Golay J, Cortiana C, Manganini M. The sensitivity of acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells carrying the t(12;21) translocation to campath‐1H‐mediated cell lysis. Haematologica 2006; 91: 322–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Golay J, Manganini M, Rambaldi A, Introna M. Effect of alemtuzumab on neoplastic B cells. Haematologica 2004; 89: 1476–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Weng WK, Levy R. Two immunoglobulin G fragment C receptor polymorphisms independently predict response to rituximab in patients with follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 3940–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cartron G, Dacheux L, Salles G et al . Therapeutic activity of humanized anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody and polymorphism in IgG Fc receptor FcγRIIIa gene. Blood 2002; 99: 754–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gennari R, Menard S, Fagnoni F et al . Pilot study of the mechanism of action of preoperative trastuzumab in patients with primary operable breast tumors overexpressing HER2. Clin Cancer Res 2004; 10: 5650–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Taylor RJ, Chan SL, Wood A et al . FccRIIIa polymorphisms and cetuximab induced cytotoxicity in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42. Louis E, El Ghoul Z, Vermeire S et al . Association between polymorphism in IgG Fc receptor IIIa coding gene and biological response to infliximab in Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 19: 511–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shields RL, Namenuk AK, Hong K et al . High resolution mapping of the binding site on human IgG1 for FcgRI, FcgRII, FcgRIII, and FcRn and design of IgG1 variants with improved binding to the FcgR. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 6591–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kabat EA, Wu TT, Perry HM, Gottesman KS, Foeller C. Sequence of proteins of immunological interest. US Dept. Health and Human Services 1991; 5th edition.

- 45. Stavenhagen JB, Gorlatov S, Tuaillon N et al . Enhancing the potency of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies via Fc optimization. Adv Enzyme Regul 2008; 48: 152–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lazar GA, Dang W, Karki S et al . Engineered antibody Fc variants with enhanced effector function. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2006; 103: 4005–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Boyd PN, Lines AC, Patel AK. The effect of the removal of sialic acid, galactose and total carbohydrate on the functional activity of Campath‐1H. Mol Immunol 1995; 32: 1311–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lifely MR, Hale C, Boyce S, Keen MJ, Phillips J. Glycosylation and biological activity of CAMPATH‐1H expressed in different cell lines and grown under different culture conditions. Glycobiology 1995; 5: 813–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Umana P, Jean‐Mairet J, Moudry R, Amstutz H, Bailey JE. Engineered glycoforms of an antineuroblastoma IgG1 with optimized antibody dependent cellular cytotoxic activity. Nat Biotechnol 1999; 17: 176–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Davies J, Jiang LY, Pan LZ, LaBarre MJ, Anderson D, Reff M. Expression of GnTIII in a recombinant anti‐CD20 CHO production cell line: expression of antibodies with altered glycoforms leads to an increase in ADCC through higher affinity for FcγRIII. Biotechnol Bioeng 2001; 74: 288–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Narisimhan S. Control of glycoprotein synthesis. UDP‐GlcNAc:glycopeptide beta 4‐N‐acetylglucosaminyltransferase III, an enzyme in hen oviduct which adds GlcNAc in beta 1–4 linkage to the beta‐linked mannose of the trimannosyl core of N‐glycosyl oligosaccharides. J Biol Chem 1982; 257: 10235–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shinkawa T, Nakamura K, Yamane N et al . The absence of fucose but not the presence of galactose or bisecting N‐acetylglucosamine of human IgG1 complex‐type oligosaccharides shows the critical role of enhancing antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 3466–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yamane‐Ohnuki N, Kinoshita S, Inoue‐Urakubo M et al . Establishment of FUT8 knockout chinese hamster ovary ells: an ideal host cell line for producing completely defucosylated antibodies with enhanced antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Biotechnol Bioeng 2004; 87: 614–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Niwa R, Sakurada M, Kobayashi Y et al . Enhanced natural killer cell binding and activation by low‐fucose IgG1 antibody results in potent antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity induction at lower antigen density. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11: 2327–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Niwa R, Shoji‐Hosaka E, Sakurada M et al . Defucosylated chimeric anti‐CC chemokine receptor 4 IgG1 with enhanced antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity shows potent therapeutic activity to T‐cell leukemia and lymphoma. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 2127–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Niwa R, Natsume A, Uehara A et al . IgG subclass‐independent improvement of antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity by fucose removal from Asn297‐linked oligosaccharides. J Immunol Methods 2005; 306: 151–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shoji‐Hosaka E, Kobayashi Y, Wakitani M et al . Enhanced Fc‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity of fc fusion proteins derived from TNF Receptor II and LFA‐3 by fucose removal from Asn‐linked oligosaccharides. J Biochem 2006; 140: 777–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Natsume A, Wakitani M, Yamane‐Ohnuki N et al . Fucose removal from complex‐type oligosaccharide enhances the antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity of single‐gene‐encoded Fc fusion protein comprising an single‐chain antibody linked the antibody constant region. J Immunol Methods 2005; 306: 93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Satoh M, Iida S, Shitara K. Non‐fucosylated therapeutic antibodies as next‐generation therapeutic antibodies. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2006; 6: 1161–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Javaud C, Dupuy F, Maftah A et al . Ancestral exonic organization of FUT8, the gene encoding the alpha6‐fucosyltransferase, reveals successive peptide domains which suggest a particular three‐dimensional core structure for the alpha6‐fucosyltransferase family. Mol Biol Evol 2000; 17: 1661–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yamane‐Ohnuki N, Yamano K, Satoh M. Biallelic gene knockouts in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Methods Mol Biol 2008; 435: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Niwa R, Hatanaka S, Shoji‐Hosaka E et al . Enhancement of the antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity of low‐fucose IgG1 is independent of FcgammaRIIIa functional polymorphism. Clin Cancer Res 2004; 10: 6248–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Iida S, Misaka H, Inoue M et al . Nonfucosylated therapeutic IgG1 antibody can evade the inhibitory effect of serum immunoglobulin G on antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity through its high binding to FcγRIIIa. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12: 2879–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hutas G. Ocrelizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against CD20 for inflammatory disorders and B‐cell malignancies. Cuur Opin Invest Drugs 2008; 9: 1206–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bowles JA, Wang SY, Link BK et al . Anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody with enhanced affinity for CD16 activates NK cells at lower concentrations and more effectively than rituximab. Blood 2006; 108: 2648–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Salles GA, Morschhauser F, Cartron G et al . A phase I/II study of RO5072759 (GA101) in patients with relapsed/refractory CD20+ malignant disease. 50th American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting 2008; #234.

- 67. Ishida T, Utsunomiya A, Iida S et al . Clinical significance of CCR4 expression in adult T‐cell leukemia/lymphoma: its close association with skin involvement and unfavorable outcome. Clin Cancer Res 2003; 9: 3625–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ishida T, Ueda R. CCR4 as a novel molecular target for immunotherapy of cancer. Cancer Sci 2006; 97: 1139–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Yamamoto K, Tobinai K, Utsunomiya A et al . Phase I study of KW‐0761, a defucosylated anti‐CCR4 antibody, in relapsed patient (Pts) with adult T‐cell leukemia‐lymphoma (ATL) or peripheral T‐cell lymphoma (PTCL): updated results. 50th American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting 2008; Poster: #1007.

- 70. Anolik JH, Campbell D, Felgar RE et al . The relationship of FcgammaRIIIa genotype to degree of B cell depletion by rituximab in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2003; 48: 455–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. A MEDI‐563, and anti‐interleukin‐5 receptor antibody, is well tolerated and induces reversible blood eosinopenia in mild asthma in a Phase I trial. MI‐CP‐158. Proceedings of the 5th Biennial Symposium of the International Eosinophil Society; 18–22 July 2007, Snowbird, UT, USA, 2007.

- 72. Gaetano ND, Cittera E, Nota R et al . Complement activation determines the therapeutic activity of rituximab in vivo. J Immunol 2003; 171: 1581–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kennedy AD, Beum PV, Solga MD et al . Rituximab Infusion Promotes Rapid Complement Depletion and Acute CD20 Loss in Chronic Lymophocytic Leukemia. J Immunol 2004; 172: 3280–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hagenbeek A, Gadeberg O, Johnson P et al . First clinical use of ofatumumab, a novel fully human anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody in relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma: results of a phase 1/2 trial. Blood 2008; 111: 5486–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Teeling JL, Mackus WJM, Wiegman LJJM et al . The biological activity of human CD20 monoclonal antibodies is linked to unique epitopes on CD20. J Immunol 2006; 177: 362–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Coiffier B, Lepretre S, Pedersen LM et al . Safety and efficacy of ofatumumab, a fully human monoclonal anti‐CD20 antibody, in patients with relapsed or refractory B‐cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a phase 1–2 study. Blood 2008; 111: 1094–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Golay J, Zaffaroni L, Vaccari T et al . Biologic response of B lymphoma cells to anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab in vitro: CD55 and CD59 regulate complement‐mediated cell lysis. Blood 2000; 95: 3900–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Treon SP, Mitsiades C, Mitsiades N et al . Tumor cell expression of CD59 is associated with resistance to CD20 serotherapy in patients with B‐cell malignancies. J Immunother 2001; 166: 2571–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Terui Y, Sakurai T, Mishima Y et al . Blockade of bulky lymphoma‐associated CD55 expression by RNA interference overcomes resistance to complement‐dependent cytotoxicity with rituximab. Cancer Sci 2006; 97: 72–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Idusogie EE, Wong PY, Presta LG et al . Engineered antibodies with increased activity to recruit complement. J Immunol 2001; 166: 2571–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Dall’Acqua WF, Cook KE, Damschroder MM, Woods RM, Wu H. Modulation of the effector functions of a human IgG1 through engineering of its hinge region. J Immunol 2006; 177: 1129–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Natsume A, In M, Takamura H et al . Engineered antibodies of IgG1/IgG3 mixed isotype with enhanced cytotoxic activities. Cancer Res 2008; 68: 3863–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Raghavan M, Bonagura VR, Morrison SL, Bjorkman PJ. Analysis of the pH dependence of the neonatal Fc receptor/immunoglobulin G interaction using antibody and receptor variants. Biochemistry 1995; 34: 14649–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Ghetie V, Popov S, Borvak J et al . Increasing the serum persistence of an IgG fragment by random mutagenesis. Nature Biotechnol 1997; 15: 637–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Hinton PR, Johlfs MG, Xiong JM et al . Engineered human IgG antibodies with longer serum half‐lives in primates. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 6213–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Dall’Acqua WF, Kiener PA, Wu H. Properties of human IgG1s engineered for enhanced binding to the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn). J Biol Chem 2006; 281: 23514–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]