Abstract

The mdm2 and mdmx oncogenes play essential yet nonredundant roles in synergistic inactivatiosn of p53. However, the biochemical mechanism by which Mdmx synergizes with Mdm2 to inhibit p53 function remains obscure. Here we demonstrate that, using nonphosphorylatable mutants of Mdmx, the cooperative inhibition of p53 by Mdmx and Mdm2 was associated with cytoplasmic localization of p53, and with an increase of the interaction of Mdmx to p53 and Mdm2 in the cytoplasm. In addition, the Mdmx mutant cooperates with Mdm2 to induce ubiquitination of p53 at C‐terminal lysine residues, and the integrity of the C‐terminal lysines was partly required for the cooperative inhibition. The expression of subcellular localization mutants of Mdmx revealed that subcellular localization of Mdmx dictated p53 localization, and that cytoplasmic Mdmx tethered p53 in the cytoplasm and efficiently inhibited p53 activity. RNAi‐mediated inhibition of Mdmx or introduction of the nuclear localization mutant of Mdmx reduced cytoplasmic retention of p53 in neuroblastoma cells, in which cytoplasmic sequestration of p53 is involved in its inactivation. Our data indicate that cytoplasmic tethering of p53 mediated by Mdmx contributes to p53 inactivation in some types of cancer cells. (Cancer Sci 2009; 100: 1291–1299)

The p53 tumor suppressor plays a central role in the prevention of tumorigenesis.( 1 , 2 ) p53 exerts its function as a tumor suppressor by transcriptionally activating numerous target genes that are involved in inducing a variety of biological outcomes.( 3 , 4 , 5 ) It is increasingly becoming evident that two related oncogenes, mdm2 and mdmx, play central roles in the regulation of p53 activity.( 6 , 7 )

Analyses of knockout mice revealed that mdmx and mdm2 suppress p53 in a nonredundant yet synergistic manner.( 8 ) Mdmx and Mdm2 functionally cooperate to inhibit p53( 9 , 10 ) and these inhibitors form a heterodimer complex through their RING finger domains.( 11 , 12 ) Thus, Mdmx and Mdm2 play distinct yet cooperative functions for p53 inactivation, presumably via their physical interaction.

Mdm2 inactivates p53 by targeting it for ubiquitin‐mediated proteasomal degradation and by promoting its transport from the nucleus into the cytoplasm,( 13 ) and it is likely that inhibition of p53 by Mdm2 is attributed to these functions. Both functions of Mdm2 require the RING finger domain, which possesses E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. Indeed, Mdm2 functions as an E3 ubiquitin ligase for p53( 14 ) although it has been reported that Mdm2 inhibits p53 via other mechanisms.( 15 )

In contrast to Mdm2, Mdmx lacks robust activity of an E3 ubiquitin ligase for p53( 16 ) although Mdmx possesses a RING finger domain with high sequence similarity to that of Mdm2. In accordance with its inability to ubiquitinate p53 by itself, Mdmx‐dependent inhibition of the transcriptional activity of p53 is independent of p53 degradation.( 17 ) Recently, it was reported that Mdmx can complement the E3 activity of C‐terminal mutants of Mdm2, suggesting that Mdmx contributes to p53 suppression in a manner distinct from Mdm2.( 18 , 19 )

In the present paper, by using nonphosphorylatable Mdmx mutants that are resistant to degradation by Mdm2, we showed that Mdmx and Mdm2 synergistically induce the cytoplasmic retention of p53 in DNA transfection assays. We demonstrated that cytoplasmic Mdmx, but not nuclear Mdmx, efficiently cooperates with Mdm2 to keep p53 in the cytoplasm and inhibits p53 activity. Further, RNAi‐mediated inhibition of Mdmx or introduction of nuclear localization mutants of Mdmx reduced cytoplasmic retention of p53 in neuroblastoma cells. It has been documented that p53 is sequestered in the cytoplasm in some types of cancer, such as neuroblastoma, and the sequestration of p53 is likely to contribute to its inactivation. We will discuss how Mdmx and Mdm2 contribute to cytoplasmic sequestration of p53, and its implication during development of some types of cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines. H1299 and U2OS cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum.

Antibodies. Anti‐Flag antibody (M2) was purchased from Sigma. Anti‐p53 monoclonal antibody (DO‐1) was purchased from Calbiochem. Anti‐HA antibody was purchased from Roche (F Hoffmam‐La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland). Anti‐myc‐tag antibody (9E10), anti‐GFP antibody (B‐2), anti‐topoisomerase I antibody (C‐2), anti‐γ tubulin antibody (D‐10), and anti‐Mdmx antibody (D‐19) were purchased from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA).

DNA transfection. In DNA transfection experiments, 2 µg DNA and 4 µL Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) were introduced per 2.0 × 105 cells. Transfected cells were then incubated for 20 h before harvesting. In experiments in which the subcellular localization mutants of Mdmx were transfected to determine localization of endogenous p53, Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used instead according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Luciferase assay. Twenty hours after transfection, cells were lysed and luciferase activity was measured using the Dual‐Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI). Mean values (±SD) from three independent experiments were determined. Basal promoter activity expressed in the absence of HA‐p53 was measured and subtracted in each experiment.

Immunostaining. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min, washed with 1× PBS, and permeabilized in 100% methanol for 30 min at –20°C. The fixed cells were then used for immunostaining as previously described.( 20 )

shRNA infection. SH‐SY5Y cells or IMR‐32 cells were infected with lentiviruses as previously described.( 21 ) Cells were infected with the control lentiviruses or the viruses that expressed the specific Mdmx shRNA overnight, incubated for an additional 2 days, and used for western blot analyses or immunostaining.

Additional information on Materials and Methods is provided in the Supporting Information.

Results

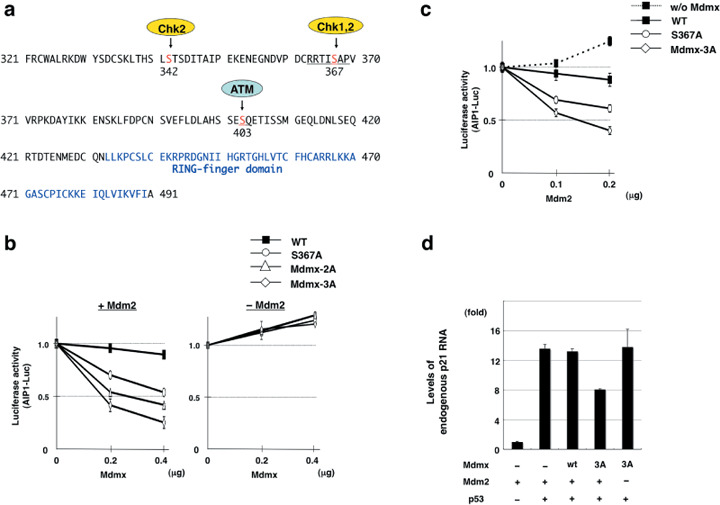

Non‐phosphorylatable Mdmx effectively cooperates with Mdm2 to suppress p53 activity in H1299. Cellular stresses such as DNA damage cause degradation of Mdmx, via its phosphorylation by damage‐induced kinases.( 22 ) Serine 367 (S367) of Mdmx is phosphorylated after DNA damage, and alanine substitution of S367 (S367A), which mimics the nonphosphorylated form, promotes the cooperation between Mdmx and Mdm2 to inhibit p53 activity.( 23 ) In addition to S367, two other serine residues comprise the major phosphorylation sites of Mdmx after DNA damage.( 22 ) One of these sites, serine 403 (S403), is phosphorylated by ATM kinase,( 22 ) whereas its downstream kinases, Chk1 or Chk2, phosphorylate serine 342 (S342) and S367, and facilitate the binding of 14‐3‐3 to Mdmx( 22 , 24 , 25 , 26 ) (Fig. 1a). Phosphorylation of each site stimulates the proteasome‐mediated degradation of Mdmx via its ubiquitination by Mdm2.( 22 , 23 , 25 )

Figure 1.

Non‐phosphorylatable Mdmx cooperates with Mdm2 to suppress p53. (a) Schematic representation of the positions of the Mdmx mutations. The serine residues phosphorylated after DNA damage are shown in red. The RING finger domain is shown in blue. (b,c) Inhibition of the transcriptional activity of p53 by the nonphosphorylatable mutants of Mdmx. (b) The indicated amounts of the wild‐type Flag‐Mdmx or Mdmx mutants were transfected into H1299 cells together with 0.15 µg HA‐p53, 0.1 µg AIP‐luc, and Renilla luciferase in the presence (left panel) or absence (right panel) of 0.2 µg myc‐Mdm2. The total amount of transfected DNA was adjusted to 2 µg with pBluescript. Luciferase activity was measured 20 h after transfection. The numbers represent mean values ± standard deviations from experiments carried out in triplicate. The presented values were calculated as follows: value of cells transfected with the indicated amount of Mdmx/value of cells transfected without Mdmx. (c) The indicated amounts of myc‐Mdm2 were transfected into H1299 cells together with 0.15 µg HA‐p53, AIP‐luc, Renilla luciferase, in the presence of 0.4 µg control vector, wild‐type Flag‐Mdmx, or the indicated Mdmx mutant. Luciferase assays were carried out as described in (b). (d) H1299 cells were cotransfected as described in (b). Total RNA prepared from transfected cells was used to measure the levels of endogenous p21 RNA by real‐time RT‐PCR using Taqman probe (Applied Biosciences, Foster City, CA). Levels of p21 were normalized with those of β‐Actin.

Assuming that the phosphorylation of S342 and S403, in addition to S367, also compromises p53 suppression by Mdmx, we speculated that additional alanine substitution of S342 and S403 would allow Mdmx to inhibit p53 more effectively. We created the Mdmx mutants with the alanine substitution at S342 (Mdmx‐2A) or at S342 plus S403 (Mdmx‐3A) in addition to S367A, and introduced each mutant into p53‐deficient H1299 cells together with p53 and the p53‐responsive luciferase reporter (AIP‐luc), in the presence or absence of the transfected Mdm2. Subsequently, the inhibitory effect of each Mdmx mutant on p53 activity was examined (Fig. 1b,c). Low amounts of Mdm2 were transfected so that introduction of Mdm2 alone did not inhibit p53 activity (Fig. 1c). As we reported previously,( 23 ) the S367A mutation augmented the inhibition of p53 activity by Mdmx in the presence of transfected Mdm2 (Fig. 1b,c). The additional alanine substitution at S342 and S403 enhanced the ability of Mdmx to suppress p53 (Fig. 1b,c). In contrast, none of these mutants showed an inhibitory effect on p53 activity in the absence of the transfected Mdm2 (Fig. 1b). We observed similar Mdm2‐dependent inhibition of p53 activity by Mdmx‐3A on another p53‐responsive promoter (Bax‐luc) (Supporting Information Fig. S1a). Wild‐type Mdmx had an inhibitory effect that was comparable to that of Mdmx‐3A in the presence of a chk2 inhibitor (Supporting Information Fig. S1b), suggesting that wild‐type Mdmx is capable of inhibiting p53 in the absence of inhibitory phosphorylation.

Cotransfection of Mdm2 with these mutants suppressed the inhibitory effects of p53 on cell growth (Supporting Information Fig. S1c). In accordance with the inhibition of cell growth, Mdmx‐3A, but not wild‐type Mdmx, inhibits RNA expression of endogenous p21, which is a crucial target of p53 and inhibits cell cycle progression (Fig. 1d). Taken together, these data suggest that nonphosphorylated forms of Mdmx effectively cooperate with Mdm2 to inhibit p53 function.

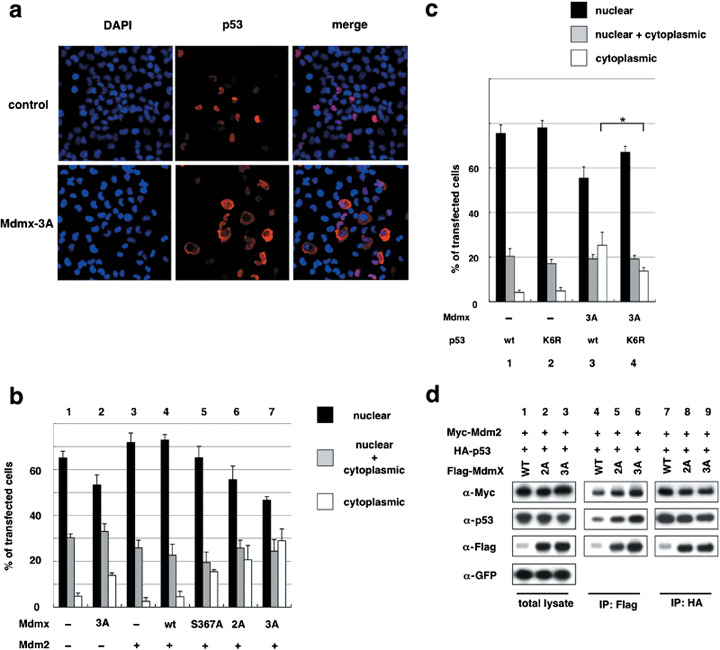

Non‐phosphorylatable Mdmx cooperates with Mdm2 to induce cytoplasmic localization of p53 in H1299. It has been demonstrated that low levels of Mdm2 inhibit p53 by inducing nuclear export.( 27 ) In order to determine whether the nonphosphorylatable mutants of Mdmx cooperate with Mdm2 to inhibit p53 activity by stimulating cytoplasmic localization of p53, we next examined the subcellular localization of p53 after cotransfection of Mdmx, Mdm2, and p53 under the same conditions described in Figure 1(b). Introduction of Mdm2 alone did not significantly affect nuclear localization of p53 (Fig. 2a,b). Although cointroduction of Mdm2 and wild‐type Mdmx had only a marginal effect on enhancement of cytoplasmic localization of p53 (Fig. 2b), cointroduction of Mdm2 and Mdmx‐3A markedly enhanced a fraction of transfected cells with cytoplasmic p53 staining (Fig. 2a,b). Cytoplasmic localization of p53 induced by Mdmx‐3A alone was much less striking if compared to that induced by Mdm2 and Mdmx‐3A (Fig. 2b), indicating that the effect of Mdmx‐3A on the subcellular localization is largely dependent on the cointroduced Mdm2. Of note, there was a gradual enhancement of the cytoplasmic localization of p53 as Mdmx harbored an increasing number of alanine mutations at the phosphorylation sites (i.e. Mdmx‐wt < S367A < 2A < 3A) (Fig. 2b), indicating that the extent of the stimulation of the cytoplasmic localization by the nonphosphorylatable mutations parallels their inhibitory effect on p53 activity (Fig. 1b). The cooperative effect of Mdmx‐3A and Mdm2 to stimulate cytoplasmic localization of p53 was also observed in U2OS cells (Supporting Information Fig. S2a).

Figure 2.

Non‐phosphorylatable Mdmx cooperates with Mdm2 to induce cytoplasmic localization of p53 in H1299. (a) H1299 cells were cotransfected with HA‐p53 and myc‐Mdm2, in the presence or absence of Mdmx‐3A, and used for staining with DAPI and anti‐HA antibody. Representative staining of the transfected cells is shown. (b) H1299 cells were cotransfected with the indicated Flag‐Mdmx mutants and HA‐p53 in the absence (columns 1 and 2) or presence (columns 3–7) of myc‐Mdm2, and used for staining with anti‐HA antibody. Subcellular localization of p53 of 100 transfected cells was evaluated in triplicate, and the average percentage of cells with the indicated staining pattern of p53 is shown. (c) Wild‐type HA‐p53 or HA‐p53‐K6R was transfected into H1299 cells together with myc‐Mdm2 in the presence or absence of Flag‐Mdmx‐3A. Immunostaining analyses were carried out as described in (b). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) as given by a one‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey post‐test. (d) HA‐p53, myc‐Mdm2, and GFP were transfected into H1299 together with the indicated Flag‐tagged Mdmx as described in (b), and lysates prepared from transfected cells were used for immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti‐Flag antibody (lanes 4–6) or anti‐p53 (DO‐1) antibody (lanes 7–9). The total lysates (lanes 1–3) and the immunoprecipitates were analysed by western blot analyses with the indicated antibodies.

Cellular stresses such as DNA damage cause degradation of Mdmx via its phosphorylation by damage‐induced kinases.( 22 , 28 ) Mdmx was highly phosphorylated at S367 in transfected H1299( 23 ) (K. Okamoto, unpublished data). In the presence of a chk2 inhibitor, wild‐type Mdmx is capable of inducing cytoplasmic localization of p53 to an extent comparable to that of Mdmx‐3A (Supporting Information Fig. S2b), indicating that in the absence of the inhibitory kinase, wild‐type Mdmx is capable of inhibiting p53 activity (Supporting Information Fig. S1b) and inducing cytoplasmic localization of p53. These observations suggest that Mdmx phosphorylation may occur during the procedure of DNA transfection, and that the nonphosphorylatable Mdmx mutation facilitates clear observation of the cooperative effects of Mdmx and Mdm2 on p53 inhibition, by negating the inhibitory effects of Mdmx phosphorylation.

Mutation at the C‐terminal lysines of p53 partially compromises the inhibitory effects of Mdmx‐mediated enhancement of ubiquitination and inhibition of p53. It has been documented that Mdm2 ubiquitinates p53 at the six C‐terminal lysines, the integrity of which are required for its nuclear export.( 29 , 30 ) In addition to ubiquitination, some of these lysines are targeted for other types of modification, including neddylation, acetylation, and methylation.( 31 , 32 ) Recent publications have indicated that Mdmx rescues the catalytic activity of Mdm2 mutants for ubiquitination and neddylation of p53 in vivo. ( 18 , 19 , 33 ) In order to determine whether Mdmx‐3A enhances Mdm2‐dependent p53 ubiquitination, we examined whether Mdmx enhances Mdm2‐mediated ubiquitination in transfected H1299. Indeed, Mdmx‐3A synergized with Mdm2 to induce p53 ubiquitination (Supporting Information Fig. S2c). In order to determine whether cooperative ubiquitination targets the C‐terminal lysines of p53 by Mdmx and Mdm2, we created a mutant p53 in which all six lysines at the C‐terminal domain were substituted with arginine (p53‐K6R). In vivo ubiquitination assays confirmed that the K6R mutation eliminates the majority of p53 ubiquitination in transfected H1299 (data not shown). The K6R mutation partially inhibited Mdmx‐3A‐mediated cytoplasmic localization of p53 (Fig. 2c) and transcriptional inhibition of p53 (Supporting Information Fig. S2d). Thus, modification of the six lysines is partly required for Mdmx‐dependent cytoplasmic localization and inactivation of p53, yet there exist other mechanisms by which Mdmx and Mdm2 cooperate to suppress p53 function.

Non‐phosphorylatable mutations of Mdmx increase levels of the association of Mdmx to Mdm2 and p53. Next we determined whether the nonphosphorylatable mutations of Mdmx affect the levels of transfected p53, Mdm2, and Mdmx as well as the interaction among them (Fig. 2d). Mdmx‐2A or Mdmx‐3A expression did not markedly decrease the levels of p53 (Fig. 2d). In contrast, both the Mdmx‐2A and Mdmx‐3A mutations clearly increased the levels of introduced Mdmx (Fig. 2d). The levels of wild‐type Mdmx and the Mdmx mutants were comparable in the presence of a proteasomal inhibitor MG132 (Supporting Information Fig. S2e), suggesting that the nonphosphorylatable mutations render Mdmx less sensitive to Mdm2‐dependent proteasomal degradation.( 22 ) In accordance with increased levels of Mdmx‐2A and Mdmx‐3A, the Mdmx mutations led to increased levels of the association of Mdmx to Mdm2 and p53 (Fig. 2d). These results indicate that the nonphosphorylatable mutations, by protecting Mdmx from Mdm2‐dependent degradation, increase levels of the association of Mdmx to Mdm2 and p53.

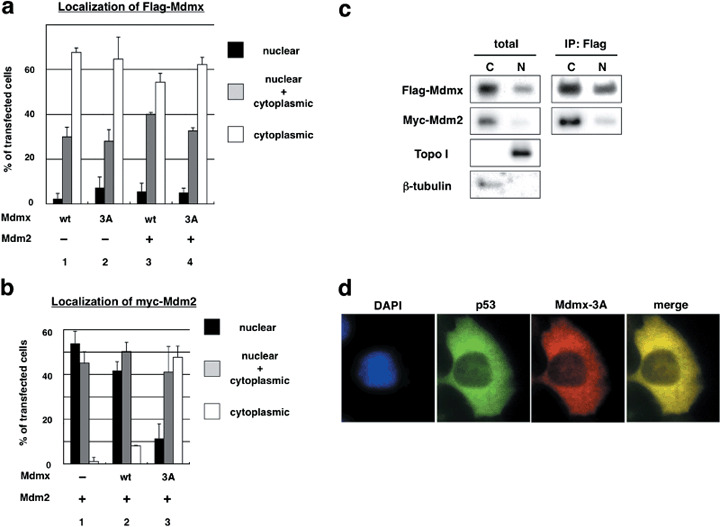

Mdmx‐3A mutation stimulates the association of Mdmx with Mdm2 and p53 predominantly in the cytoplasm. In order to examine whether the Mdmx‐3A mutation affects subcellular localization of Mdmx and/or Mdm2 as well as p53, we next carried out immunostaining analyses of transfected Mdm2 and Mdmx. In agreement with a previous report,( 10 ) transfected wild‐type Mdmx was predominantly localized to the cytoplasm (Fig. 3a). Both wild‐type Mdmx and Mdmx‐3A mainly remained in the cytoplasm either in the presence or absence of cotransfected Mdm2 (Fig. 3a). Mdm2 predominantly localized to the nucleus in the absence of transfected Mdmx (Fig. 3b). Cotranfection of wild‐type Mdmx mildly enhanced cytoplasmic localization of introduced Mdm2, and the extent of the cytoplasmic localization was markedly augmented by the Mdmx‐3A mutation (Fig. 3b). Thus, the Mdmx‐3A mutation facilitates cytoplasmic localization of cointroduced Mdm2.

Figure 3.

The Mdmx‐3A mutation stimulates the localization of Mdm2 and p53 predominantly to the cytoplasm. (a,b) HA‐p53 was transfected into H1299 cells together with the indicated Flag‐Mdmx in the presence or absence of myc‐Mdm2 as described in Figure 2(b). The transfected cells were sequentially immunostained with (a) anti‐Flag (M2) antibody or (b) antimyc antibody, antimouse IgG antibody conjugated with Alexa 595, and anti‐HA antibody conjugated with Alexa 488 (Molecular Probe). Subcellular localization of (a) Flag‐Mdmx or (b) myc‐Mdm2 in cells that express HA‐p53 was evaluated as described in Figure 2(b). (c) H1299 cells were transfected with HA‐p53 together with Flag‐Mdmx‐3A and myc‐Mdm2. The transfected cells were subjected to subcellular fractionation. The total lysates and the Flag‐immunoprecipitates were then used for western blot analyses with the indicated antibodies. Topoisomerase I and γ tubulin are shown as nuclear and cytoplasmic markers respectively. (d) Representative staining of cells that express cytoplasmic p53 and Mdmx.

The positive effects of Mdmx‐3A mutation on the levels of the Mdmx–Mdm2 complex (Fig. 2d) and on the cytoplasmic localization of Mdm2 (Fig. 3b) suggest that the mutation leads to an increase of the Mdmx–Mdm2 complex in cytoplasm. Therefore, we next examined the extent of their interaction in each subcellular compartment after subcellular fractionation. In agreement with the results of the immunostaining (Fig. 3a,b), both Mdmx‐3A and Mdm2 were mainly localized to the cytoplasm, and the Mdmx‐3A–Mdm2 complex was predominantly formed in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3c). Cytoplasmic Mdmx‐3A clearly colocalized with not only Mdm2 (data not shown) but also with p53 (Fig. 3d). Analyses of the subcellular localization of Mdmx‐3A and p53 or of Mdmx‐3A and Mdm2 in individual cells revealed that localization of Mdmx‐3A in the cytoplasm was clearly associated with cytoplasmic localization of p53 (Supporting Information Fig. S3a) and Mdm2 (Supporting Information Fig. S3b). These data indicate that the Mdmx‐3A mutation leads to an increase in the association of Mdmx with p53 and Mdm2 in the cytoplasm.

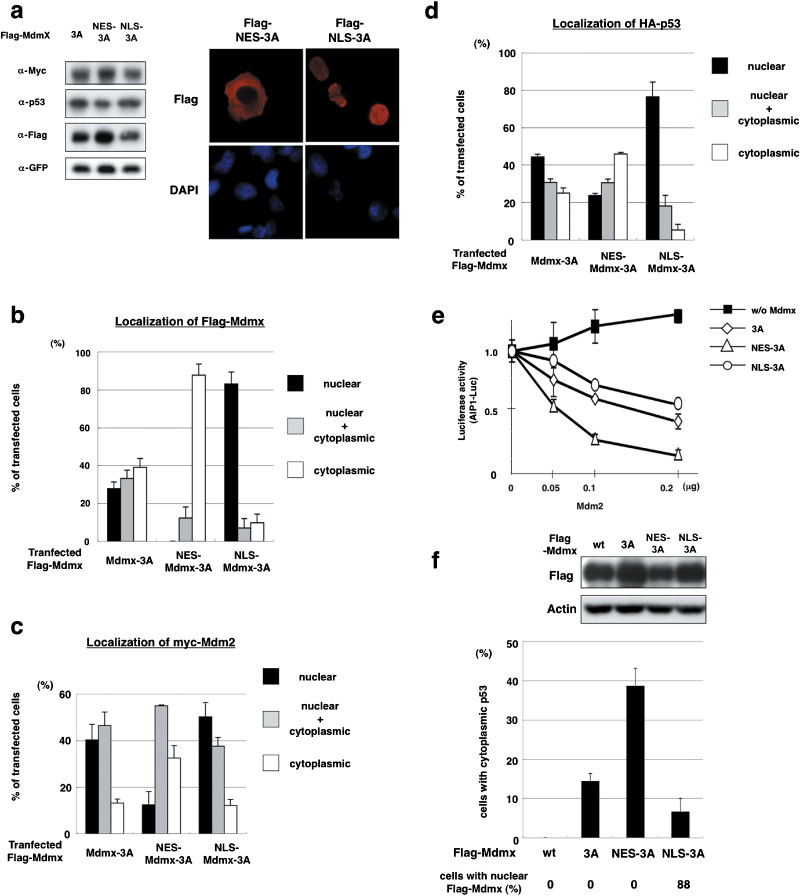

Cytoplasmic Mdmx is responsible for p53 localization in cytoplasm. In order to determine whether cytoplasmic Mdmx‐3A induces localization of p53 to the cytoplasm, we generated Mdmx mutants in which either a peptide that corresponds to a nuclear localization signal of SV40 large T antigen (PKKKRKV) or a nuclear export signal of Rev of human immunodeficiency virus type‐1 (LQLPPLERLTL) was connected to Mdmx‐3A (NLS‐Mdmx‐3A or NES‐Mdmx‐3A). Subsequently, we introduced these Mdmx mutants together with Mdm2 and p53, and evaluated the effect of subcellular localization of Mdmx‐3A on Mdm2 and p53. As expected, NLS‐Mdmx‐3A and NES‐Mdmx‐3A showed predominant localization to nuclei and cytoplasm respectively (Fig. 4a,b). Clear cytoplasmic localization of Mdm2 (Fig. 4c) and p53 (Fig. 4d) was induced by NES‐Mdmx‐3A, but not by NLS‐Mdmx‐3A. Inhibition of transcriptional activity of p53 by Mdmx‐3A was enhanced by NES‐Mdmx‐3A and rather reduced by NLS‐Mdmx‐3A (Fig. 4e). Thus, cytoplasmic Mdmx‐3A tethers p53 to the cytoplasm, whereas it effectively inhibits p53 activity in transfected H1299 cells.

Figure 4.

Cytoplasmic Mdmx tethers p53 and Mdm2 to the cytoplasm and stimulates p53 inhibition. (a) H1299 cells were cotransfected with HA‐p53, myc‐Mdm2, GFP, and the indicated Flag‐tagged Mdmx. Left panel, western blot analyses with the indicated antibodies. Right panel, representative staining with anti‐Flag antibody and DAPI. (b–d) H1299 cells were transfected with the indicated Mdmx, together with myc‐Mdm2, and immunostained with (b) anti‐Flag antibody, (c) anti‐Mdm2 antibody, or (d) anti‐HA antibody. Subcellular localization of transfected (b) Mdmx, (c) Mdm2, or (d) p53 was represented as described in Figure 2(b). (e) Flag‐Mdmx mutant or the control vector was transfected into H1299 cells together with HA‐p53, in the presence of the indicated amounts of myc‐Mdm2, and luciferase assays were carried out as described in Figure 1(c). (f) U2OS cells were transfected with the indicated Flag‐Mdmx. Upper panel, western blot analyses with the anti‐Flag or the anti‐actin antibodies. Lower panel, cells transfected with the indicated plasmids were immunostained with the anti‐Flag and antip53 (CM1) antibodies, and a fraction of the transfected cells with cytoplasmic p53 staining was quantified.

Mdmx in the cytoplasm promotes cytoplasmic retention of endogenous p53. Next we examined whether subcellular localization of Mdmx‐3A dictates localization of endogenous p53. Wild‐type Mdmx, Mdmx‐3A, NES‐Mdmx‐3A, or NLS‐Mdmx‐3A was introduced into U2OS cells, in which wild‐type p53 is expressed predominantly in nuclei,( 34 ) and we determined whether the mutants affect the subcellular localization of endogenous p53. The Mdmx‐3A mutants were expressed at comparable levels (Fig. 4f). As we observed in H1299, NLS‐Mdmx‐3A and NES‐Mdmx‐3A predominantly localized to nuclei and cytoplasm respectively (data not shown). Introduction of wild‐type Mdmx did not significantly affect nuclear localization of p53. In contrast, introduction of the Mdmx‐3A mutants induced localization of p53 to the cytoplasm, and a striking enhancement of cytoplasmic localization of p53 was observed in the presence of NES‐Mdmx‐3A (Fig. 4f). Taken together, these data indicate that cytoplasmically located Mdmx, presumably by tethering p53, induces localization of endogenous p53 to the cytoplasm.

Both Mdmx and Mdm2 predominantly localize to the cytoplasm of neuroblastoma cells. Inactivation of p53 via its cytoplasmic localization is frequently observed in some types of cancer such as neuroblastoma,( 35 ) and yet the precise mechanism by which p53 is sequestered in cytoplasm remains obscure. It was reported that Mdm2 mediates the cytoplasmic retention of p53 in neuroblastoma.( 36 , 37 ) In order to examine whether Mdmx as well as Mdm2 is involved in p53 inactivation via cytoplasmic sequestration in neuroblastoma, we analyzed SH‐SY5Y and IMR‐32 cells that, like most other neuroblastoma cells, harbor wild‐type p53 with cytoplasmic localization (Fig. 5a; Supporting Information Fig. S4a). Expression levels of Mdmx in SH‐SY5Y were much higher than those in normal human fibroblasts, and even higher than those in MCF‐7 (data not shown), breast cancer cells in which the mdmx gene is amplified and Mdmx is expressed at high levels.( 38 ) Both Mdmx and Mdm2 predominantly localized to the cytoplasm in SH‐SY5Y cells (Supporting Information Fig. S4a). The extent of S367 phosphorylation in SH‐5YSY cells was much lower than that in the transfected H1299 cells (Supporting Information Fig. S4c). These observations suggest that Mdmx is expressed, probably in nonphosphorylated forms, at high levels in the cytoplasm in unstressed SH‐SY5Y cells.

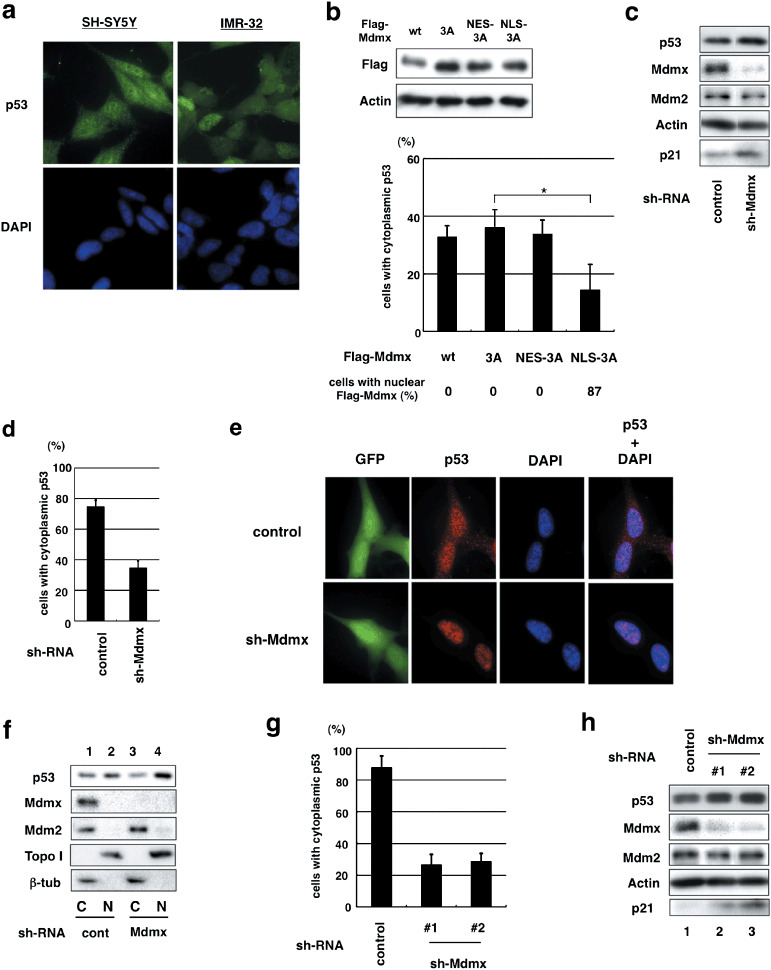

Figure 5.

Mdmx is required for cytoplasmic retention of p53 in neuroblastoma cells. (a) Cytoplasmic retention of p53 in neuroblastoma. SH‐SY5Y or IMR‐32 cells were stained with antip53 antibody (CM1) and DAPI. (b) SH‐SY5Y cells were transfected with the indicated Flag‐tagged Mdmx. Western blot analyses and quantification of a fraction of cells with cytoplasmic p53 were carried out as described in Figure 4(f). (c–f) SH‐SY5Y cells were infected with the control lentivirus or the viruses expressing Mdmx shRNA. (c) Lysates prepared from the infected cells were used for western blot analyses with the indicated antibodies. (d) The infected cells were immunostained with antip53 polyclonal antibody (CM1) and DAPI. The average percentage of the infected cells with cytoplasmic staining of p53 was presented after evaluating subcellular localization of p53 of 100 cells in triplicate. (e) Representative pictures of staining of cells that were infected with the control lentiviruses or the viruses that express Mdmx shRNA. Note that the viruses express GFP, and infection efficiency is ~100% judging from GFP expression. (f) Subcellular fractionation and western blot analyses were carried out with the indicated antibodies. (g,h) IMR‐32 cells were infected with the control lentiviruses or the viruses that express Mdmx shRNA, and (g) western blot analyses or (h) the quantification of subcellular distribution of p53 was carried out as described in (c) and (d) respectively.

Nuclear Mdmx inhibits cytoplasmic retention of p53 in SH‐SY5Y. In order to determine whether subcellular localization of Mdmx‐3A dictates localization of endogenous p53 in neuroblastoma cells as well as in U2OS cells, the effects of subcellular localization of wild‐type Mdmx or the Mdmx mutants on endogenous p53 localization were evaluated as described in Figure 4(f). The Mdmx‐3A mutants were expressed at comparable levels (Fig. 5b). In accordance with cytoplasmic localization of endogenous Mdmx (Supporting Information Fig. S4a), Mdmx‐3A and wild‐type Mdmx exclusively localized to the cytoplasm (Fig. 5b). As expected, the majority of NLS‐Mdmx‐3A localized to nuclei (87%) and NES‐Mdmx‐3A totally localized to the cytoplasm. Immunostaining of transfected SH‐SY5Y cells revealed that the expression of NLS‐Mdmx‐3A, but not NES‐Mdmx‐3A, reduced cytoplasmic localization of p53 (Fig. 5b), indicating that nuclear expression of Mdmx‐3A inhibits cytoplasmic retention of p53 in SH‐SY5Y.

Mdmx is required for inactivation of p53 in neuroblastoma cells. In order to further examine the role of Mdmx in p53 inactivation in neuroblastoma cells, we inhibited Mdmx expression by infecting cells with the lentiviruses expressing Mdmx shRNA. Mdmx inhibition by the specific shRNA, while not significantly affecting levels of p53, induced expression of p21, a crucial p53 target (Fig. 5c) and reduced the cytoplasmic localization of p53 (Fig. 5d,e). The positive role of Mdmx in cytoplasmic localization of p53 was confirmed by western blot analyses of nuclear and cytoplasmic lysates prepared from the infected cells. Depletion of Mdmx decreased p53 levels in the cytoplasm and increased those in nuclei, while the depletion did not significantly affect cytoplasmic localization of Mdm2 (Fig. 5f).

Similarly, inhibition of Mdmx by the specific shRNA led to induction of p21 expression and inhibition of cytoplasmic localization of p53 in IMR‐32, another neuroblastoma cell line (Fig. 5g,h; Supporting Information Fig. S4c). Thus, Mdmx contributes to cytoplasmic retention of p53 in neuroblastoma cells.

Discussion

Genetic evidence indicates that mdmx is a crucial inhibitor of p53 and that mdmx and mdm2 cooperatively function to inhibit p53. However, the mechanical basis of the cooperation of the oncogenes is not clearly established. In an attempt to recapitulate synergistic inhibition of p53 by Mdmx and Mdm2, we took advantage of our observation that the nonphosphorylatable mutations confer Mdmx resistance against Mdm2‐mediated degradation. We demonstrated that nonphosphorylatable mutations of Mdmx markedly enhance the ability of Mdmx to cooperate with Mdm2 for inhibition of p53, suggesting that the stress‐induced phosphorylation of Mdmx is important for its ability to suppress p53. The importance of the Mdmx phosphorylation was further supported by the functionality of wild‐type Mdmx on p53 suppression in the presence of a chk2 inhibitor (Supporting Information Figs S1b and 2b).

Through the analyses of the function of the Mdmx mutants, we found that the nonphosphorylatable mutant of Mdmx effectively cooperates with Mdm2 to induce p53 ubiquitination. The ability of the nonphosphorylatable mutations of Mdmx to inhibit p53 activity was associated with enhanced cytoplasmic retention of p53 and with increased levels of the interaction of Mdmx to p53 and Mdm2 in cytoplasm. A causal role of cytoplasmic Mdmx to induce localization of p53 in the cytoplasm was demonstrated using the Mdmx mutants that harbor autonomous subcellular localization signals.

p53 is sequestered in the cytoplasm in some types of cancer, and it is assumed that the sequestration of p53 contributes to p53 inactivation.( 35 , 39 ) Mdm2 is essential for inhibition and cytoplasmic sequestration of p53 in neuroblastoma cells,( 36 , 37 ) and the cooperative function of Mdmx and Mdm2 to induce p53 retention in the cytoplasm may contribute to its inactivation in some of cancer cells. We found that, in addition to Mdm2, Mdmx is also required for cytoplasmic sequestration of p53 in neuroblastoma cells. Considering that Mdm2 enhances the interaction between p53 and Mdmx in the transfected H1299 cells, Mdmx and Mdm2 may cooperate by stimulating the formation of a complex with p53. Of note, Mdmx stabilizes p53 via a formation of a complex with Mdm2,( 16 ) and formation of such a stable complex may account for cytoplasmic sequestration of p53.

In addition to the cytoplasmic tethering via physical interaction, regulation of post‐translational modification of the C‐terminal of p53 is likely to contribute to the cooperative inhibition of p53 by Mdm2 and Mdmx, because mutations in the six C‐terminal lysines, which are targets for the regulatory modification, partly abolished the cooperative inhibition of p53 (Supporting Information Fig. S2d). Mdm2 promotes cytoplasmic translocation of p53 via its ubiqiutination at the same lysine residues,( 27 , 40 ) and accumulating data( 9 , 18 , 19 ) as well as ours (Supporting Information Fig. 2c) indicate that Mdmx promotes Mdm2‐dependent p53 ubiquitination. Hence, it is likely that enhancement of Mdm2‐dependent ubiquitination of p53 by Mdmx also contributes to the cooperative inhibition of p53 activity by these oncoproteins. In fact, the cytoplasmic retention of p53 in neuroblastoma is in part attributed to multimono‐ubiquitination of p53 due to defective function of HAUSP, a de‐ubiquitinating enzyme for p53 and Mdmx and Mdm2.( 34 , 41 , 42 ) However, we did not observe a significant change in the pattern of p53 laddering, which presumably represents ubiquitinated p53, in neuroblastoma cells after knock down of Mdmx (data not shown). The two mechanisms that mediate cytoplasmic localization of p53, namely cytoplasmic tethering and ubiquitin‐dependent translocation, are not mutually exclusive, and presumably contribute to cytoplasmic retention of p53 by Mdmx.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. Non‐phosphorylatable Mdmx cooperates with Mdm2 to suppress p53.

Fig. S2. Non‐phosphorylatable Mdmx cooperates with Mdm2 to induce cytoplasmic localization of p53 in H1299.

Fig. S3. The Mdmx‐3A mutation stimulates the localization of Mdm2 and p53 predominantly to the cytoplasm.

Fig. S4. Mdmx is required for cytoplasmic retention of p53 in neuroblastoma cells.

Please note: Wiley‐Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Jiandong Chen and Hirofumi Arakawa for providing us with Flag‐Mdm2 and AIP‐luc respectively. We thank Kenji Kashima for experimental assistance. This work was supported by a Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (Y.T. and K.O.), a Grant‐in‐Aid for Third Term Comprehensive Control Research for Cancer from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Japan (Y.T.), the Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research (K.O.), and the Japan–France Integrated Action Program (K.O. and C.G.).

References

- 1. Braithwaite AW, Prives CL. p53: more research and more questions. Cell Death Differ 2006; 13: 877–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Levine AJ. p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell 1997; 88: 323–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oren M. Decision making by p53: life, death and cancer. Cell Death Differ 2003; 10: 431–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ko LJ, Prives C. p53: puzzle and paradigm. Genes Dev 1996; 10: 1054–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature 2000; 408: 307–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Toledo F, Wahl GM. MDM2 and MDM4: p53 regulators as targets in anticancer therapy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2007; 39: 1476–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marine JC, Dyer MA, Jochemsen AG. MDMX: from bench to bedside. J Cell Sci 2007; 120: 371–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marine JC, Francoz S, Maetens M, Wahl G, Toledo F, Lozano G. Keeping p53 in check: essential and synergistic functions of Mdm2 and Mdm4. Cell Death Differ 2006; 13: 927–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Linares LK, Hengstermann A, Ciechanover A, Muller S, Scheffner M. HdmX stimulates Hdm2‐mediated ubiquitination and degradation of p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100: 12 009–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gu J, Kawai H, Nie L et al . Mutual dependence of MDM2 and MDMX in their functional inactivation of p53. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 19 251–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tanimura S, Ohtsuka S, Mitsui K, Shirouzu K, Yoshimura A, Ohtsubo M. MDM2 interacts with MDMX through their RING finger domains. FEBS Lett 1999; 447: 5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sharp DA, Kratowicz SA, Sank MJ, George DL. Stabilization of the MDM2 oncoprotein by interaction with the structurally related MDMX protein. J Biol Chem 1999; 274: 38 189–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Michael D, Oren M. The p53–Mdm2 module and the ubiquitin system. Semin Cancer Biol 2003; 13: 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Honda R, Tanaka H, Yasuda H. Oncoprotein MDM2 is a ubiquitin ligase E3 for tumor suppressor p53. FEBS Lett 1997; 420: 25–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Coutts AS, La Thangue NB. Mdm2 widens its repertoire. Cell Cycle 2007; 6: 827–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stad R, Little NA, Xirodimas DP et al . Mdmx stabilizes p53 and Mdm2 via two distinct mechanisms. EMBO Rep 2001; 2: 1029–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Toledo F, Krummel KA, Lee CJ et al . A mouse p53 mutant lacking the proline‐rich domain rescues Mdm4 deficiency and provides insight into the Mdm2‐Mdm4‐p53 regulatory network. Cancer Cell 2006; 9: 273–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Poyurovsky MV, Priest C, Kentsis A et al . The Mdm2 RING domain C‐terminus is required for supramolecular assembly and ubiquitin ligase activity. EMBO J 2007; 26: 90–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Uldrijan S, Pannekoek WJ, Vousden KH. An essential function of the extreme C‐terminus of MDM2 can be provided by MDMX. EMBO J 2007; 26: 102–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shinozaki T, Nota A, Taya Y, Okamoto K. Functional role of Mdm2 phosphorylation by ATR in attenuation of p53 nuclear export. Oncogene 2003; 22: 8870–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Laurie NA, Donovan SL, Shih CS et al . Inactivation of the p53 pathway in retinoblastoma. Nature 2006; 444: 61–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pereg Y, Shkedy D, De Graaf P et al . Phosphorylation of Hdmx mediates its Hdm2‐ and ATM‐dependent degradation in response to DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005; 102: 5056–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Okamoto K, Kashima K, Pereg Y et al . DNA damage‐induced phosphorylation of MdmX at serine 367 activates p53 by targeting MdmX for Mdm2‐dependent degradation. Mol Cell Biol 2005; 25: 9608–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jin Y, Dai MS, Lu SZ et al . 14‐3‐3gamma binds to MDMX that is phosphorylated by UV‐activated Chk1, resulting in p53 activation. EMBO J 2006; 25: 1207–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pereg Y, Lam S, Teunisse A et al . Differential roles of ATM‐ and Chk2‐mediated phosphorylations of Hdmx in response to DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol 2006; 26: 6819–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen L, Gilkes DM, Pan Y, Lane WS, Chen J. ATM and Chk2‐dependent phosphorylation of MDMX contribute to p53 activation after DNA damage. EMBO J 2005; 24: 3411–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shmueli A, Oren M. Regulation of p53 by Mdm2: fate is in the numbers. Mol Cell 2004; 13: 4–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lopez‐Pajares V, Kim MM, Yuan ZM. Phosphorylation of MDMX mediated by Akt leads to stabilization and induces 14‐3‐3 binding. J Biol Chem 2008; 283: 13707–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gu J, Nie L, Wiederschain D, Yuan ZM. Identification of p53 sequence elements that are required for MDM2‐mediated nuclear export. Mol Cell Biol 2001; 21: 8533–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lohrum MA, Woods DB, Ludwig RL, Balint E, Vousden KH. C‐terminal ubiquitination of p53 contributes to nuclear export. Mol Cell Biol 2001; 21: 8521–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Xirodimas DP, Saville MK, Bourdon JC, Hay RT, Lane DP. Mdm2‐mediated NEDD8 conjugation of p53 inhibits its transcriptional activity. Cell 2004; 118: 83–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Toledo F, Wahl GM. Regulating the p53 pathway: in vitro hypotheses, in vivo veritas. Nat Rev Cancer 2006; 6: 909–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Singh RK, Iyappan S, Scheffner M. Hetero‐oligomerization with MdmX rescues the ubiquitin/Nedd8 ligase activity of RING finger mutants of Mdm2. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 10 901–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Becker K, Marchenko ND, Maurice M, Moll UM. Hyperubiquitylation of wild‐type p53 contributes to cytoplasmic sequestration in neuroblastoma. Cell Death Differ 2007; 14: 1350–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moll UM, LaQuaglia M, Benard J, Riou G. Wild‐type p53 protein undergoes cytoplasmic sequestration in undifferentiated neuroblastomas but not in differentiated tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995; 92: 4407–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lu W, Pochampally R, Chen L, Traidej M, Wang Y, Chen J. Nuclear exclusion of p53 in a subset of tumors requires MDM2 function. Oncogene 2000; 19: 232–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rodriguez‐Lopez AM, Xenaki D, Eden TO, Hickman JA, Chresta CM. MDM2 mediated nuclear exclusion of p53 attenuates etoposide‐induced apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells. Mol Pharmacol 2001; 59: 135–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Danovi D, Meulmeester E, Pasini D et al . Amplification of Mdmx (or Mdm4) directly contributes to tumor formation by inhibiting p53 tumor suppressor activity. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24: 5835–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jimenez GS, Khan SH, Stommel JM, Wahl GM. p53 regulation by post‐translational modification and nuclear retention in response to diverse stresses. Oncogene 1999; 18: 7656–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li M, Brooks CL, Wu‐Baer F, Chen D, Baer R, Gu W. Mono‐versus polyubiquitination: differential control of p53 fate by Mdm2. Science 2003; 302: 1972–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li M, Brooks CL, Kon N, Gu W. A dynamic role of HAUSP in the p53–Mdm2 pathway. Mol Cell 2004; 13: 879–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Meulmeester E, Maurice MM, Boutell C et al . Loss of HAUSP‐mediated deubiquitination contributes to DNA damage‐induced destabilization of Hdmx and Hdm2. Mol Cell 2005; 18: 565–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Non‐phosphorylatable Mdmx cooperates with Mdm2 to suppress p53.

Fig. S2. Non‐phosphorylatable Mdmx cooperates with Mdm2 to induce cytoplasmic localization of p53 in H1299.

Fig. S3. The Mdmx‐3A mutation stimulates the localization of Mdm2 and p53 predominantly to the cytoplasm.

Fig. S4. Mdmx is required for cytoplasmic retention of p53 in neuroblastoma cells.

Please note: Wiley‐Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item