Abstract

It was hypothesized that four histopathological types or subtypes of breast carcinoma were undifferentiated types characterized by bidirectional differentiation toward both luminal epithelial and myoepithelial cells and had characteristic molecular changes: invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) with a large central acellular zone, atypical medullary carcinoma (a subgroup in Grade 3 solid‐tubular carcinoma), matrix‐producing carcinoma, and spindle‐cell carcinoma (or carcinoma with spindle‐cell metaplasia). In 32 cases of the undifferentiated type and 37 cases of the relatively differentiated types, we immunohistochemically examined the expressions of myoepithelial markers and KIT, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and c‐erbB‐2 oncoproteins. Vimentin, S‐100, and α‐smooth muscle actin were positive in 28 (88%), 22 (69%), and 15 (47%) of the undifferentiated types, but were positive in seven (19%), one (3%), and one (3%) of relatively differentiated types (P < 0.0001). KIT and EGFR overexpressions were detected more frequently in the undifferentiated types (34 and 88%, respectively) than in relatively differentiated types (3 and 3%, respectively) (P < 0.0001, for both). In 11 (85%) of 13 cases with KIT overexpression, EGFR overexpression concurred. c‐erbB‐2 overexpression was almost equally detected in both the undifferentiated and relatively differentiated types, and did not correlate with KIT or EGFR overexpression. Phosphotyrosine was detected in 16 (67%) of 24 cases with KIT, EGFR, and/or c‐erbB‐2 overexpression but only in six (18%) of 34 cases without KIT, EGFR, or c‐erbB‐2 overexpression (P = 0.0002). The undifferentiated‐type breast carcinomas appeared to show mammary epithelial stem cell‐like features, and they could be identified by KIT and/or EGFR overexpressions. (Cancer Sci 2005; 96: 333–339)

In recent studies, mammary epithelial stem cells were shown to play roles in proliferation and remodeling of the mammary gland, and are also considered to be the primary targets for tumorigenesis in the adult mammary glands.( 1 ) The stem cells also form the tumor stem‐cell population. The mammary epithelial stem cells are undifferentiated cells and have potential of self‐renewal by symmetrical or asymmetrical cell division and bidirectional differentiation to either luminal epithelial cells or myoepithelial cells through the stage of transit amplifying cells (or progenitor cells).( 1 ) A stem cell is likely to be a small, undifferentiated cell that does not express markers of full differentiated myoepithelial and luminal epithelial cells, although the combinations of certain markers for both lineages have been suggested as being characteristics of the stem cells.( 2 )

In a previous study, we reported that the expression of myoepithelial cell markers, for example, vimentin, α‐smooth muscle actin, and S‐100 protein, were frequent in invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) of solid‐tubular subtype, nuclear grade 3, of the breast.( 3 ) Vimentin, a mesenchymal marker, is also shown to be a molecule expressed by myoepithelial cells.( 2 ) Therefore, it is compatible to consider that these immunophenotype observed in this breast carcinoma type would indicate its bidirectional differentiation toward luminal epithelial and myoepithelial cells.

The KIT proto‐oncogene encodes a growth factor receptor with tyrosine kinase activity and is involved in the growth and development of mast cells and of premature stromal cell or interstitial cell of Cajal.( 4 , 5 ) Among human tumors, mutational activation of the KIT proto‐oncogene is frequent in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), which is suggested to originate from a premature stromal cell.( 6 ) The EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor, or c‐erbB‐1, HER‐1) proto‐oncogene also encodes growth factor receptors with tyrosine kinase activity.( 7 ) The overexpression of EGFR oncoprotein was correlated with high grade and hormone‐receptor‐negative breast carcinomas and poorer patient prognosis.( 8 , 9 )

We found that KIT and EGFR overexpressions were detected in 10 and 8% of breast carcinomas, respectively, and were frequent in IDC of the solid‐tubular subtype, nuclear grade 3, with myoepithelial differentiation.( 3 ) Although c‐erbB‐2 (or HER‐2) overexpression also tended to be more frequent in higher grade carcinomas, its overexpression was not correlated with the expression of myoepithelial markers.( 3 )

Atypical medullary carcinoma (AMC) could constitute a significant subset of the cases of IDC, solid‐tubular subtype, grade 3.( 10 , 11 ) These myoepithelial markers were reported to be expressed frequently not only in AMC but also in several special histological types or subtypes, for example, invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) with a large central acellular zone, matrix‐producing carcinoma (MPC), and spindle‐cell carcinoma (SpCC), or carcinoma with spindle‐cell metaplasia.( 12 , 13 , 14 )

These four histological types/subtypes often coexist as components in a carcinoma lesion, and show mutual transition.( 15 , 16 ) From these observations, we speculated that these four breast carcinoma types/subtypes are histological spectra of the undifferentiated‐type breast carcinomas.

In the present study, we hypothesized that overexpression of KIT and/or EGFR is characteristic of undifferentiated‐type invasive breast carcinomas, which were characterized by bidirectional differentiation. To test this hypothesis, we immunohistochemically examined the expression of the KIT, EGFR, and c‐erbB‐2 oncoproteins and myoepithelial markers in the undifferentiated‐type breast carcinomas and the relatively differentiated‐type breast carcinomas and compared their expression rates between these two carcinoma groups.

Materials and Methods

Cases. We reviewed hematoxylin‐eosin‐stained tissue sections of breast carcinomas that were resected from patients who received mastectomy or partial breast resection at the National Defense Medical College Hospital between 1985 and 1990. All cases were histologically diagnosed according to the classification of Japanese Breast Cancer Society (JBCS),( 17 ) besides the isolation of MPC and IDC with a large central acellular zone as separate histological types.( 12 , 14 )

The putatively undifferentiated‐type breast carcinomas comprised IDC with a large central acellular zone, AMC, SpCC and MPC (Fig. 1). IDC with a large central acellular zone was defined as described in a previous study,( 12 ) and a small subset of scirrhous subtype and solid‐tubular subtype was included in this category. AMC was defined according to the Ridorfi's criteria, which is that AMC has features of typical medullary carcinoma but with any of the following: (i), areas of tumor margins showing focal or prominent infiltration; (ii), presence of intraductal carcinoma component; (iii), mild to negligible mononuclear infiltrate or infiltrate at margins only; (iv), nuclear grade 3; and (v), presence of microglandular features.( 10 , 11 ) A subset of IDC, solid‐tubular subtype, grade 3 held true to this category. SpCC was also defined according to JBCS, with reference to the criteria by Wargotz et al.( 13 ) MPC was defined according to the criteria by Wargotz and Norris.( 14 )

Figure 1.

Histological presentation of undifferentiated‐type breast carcinomas. (a, b) Invasive ductal carcinoma with a large central acellular zone (c) atypical medullary carcinoma, and (d) matrix‐producing carcinoma. In (a), the boundary of the cancer area from mammary gland tissue is indicated by arrows, and the central acellular zone is indicated by arrowheads. Hematoxylin‐eosin stain.

The relatively differentiated‐type breast carcinomas comprised others, for example, IDC not otherwise specified (NOS), mucinous carcinoma, and invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC). We defined IDC‐NOS here as cases of IDC other than IDC with a large central acellular zone, AMC, or MPC. Therefore, IDC‐NOS comprises papillotubular subtype, a majority of solid‐tubular subtype, but not IDC with a large central acellular zone, AMC or MPC, and a majority of scirrhous subtype, but not IDC with a large central acellular zone.

We collected typical cases of the four undifferentiated types, three relatively differentiated types, and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Typical cases of each histological type were consecutively collected, and we could include seven IDC with a large central acellular zone, nine AMC, one MPC, 28 cases of IDC‐NOS, three mucinous carcinomas, six ILC, and six DCIS.

In order to supplement the number of cases of the undifferentiated types, we included four IDC with a large central acellular zone, one AMC, three MPC, and three SpCC from the case file of the National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo, and three MPC resected at the JA Suzuka General Hospital between 1996 and 2002. In total, we included 69 invasive breast carcinoma comprising 32 cases of the undifferentiated types and 37 cases of relatively differentiated types, and six cases of DCIS.

From the viewpoint of nuclear grade, 69 invasive carcinomas were classified into seven cases of Grade 1, 24 cases of Grade 2, and 38 cases of Grade 3.( 15 ) In six cases of DCIS, two and four were comedo and cribriform types, respectively.

Immunohistochemistry. The expressions of vimentin, S‐100, α‐SMA, CD34, KIT, EGFR, and c‐erbB‐2 were examined by immunohistochemistry (IHC) in the 75 breast carcinomas. In 58 cases from which additional tissue sections were available, tyrosine phosphorylation was also examined. In 67 cases, the expressions of estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PgR) were also examined. Routinely processed formalin‐fixed paraffin‐embedded tissue specimens were cut into 4‐µm‐thick sections. Antibodies used are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Antibodies used in the study

| Molecule | Clone | Manufacturer | Dilution | Pretreatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vimentin (M) | V9 | Dakocytomation (Grostrup, Denmark) | 1:200 | None |

| S‐100 (P) | Dakocytomation | 1:2000 | None | |

| α‐SMA (M) | 1A4 | Shandon‐Lipshaw | 1:15 | None |

| CD34 (M) | QBent10 | Dakocytomation | 1:50 | MW 95°C, 15 min in 10 mM sodium citrate (pH 6) |

| KIT (P) | Dakocytomation | 1:50 | Incubate at 95°C for 20 min in 10 mM sodium citrate (pH 6) with 0.1% Tween40 | |

| EGFR (M) | 31G7 | Zymed (South San Francisco, CA) | 1:50 | 0.1% type XXIV protease (Sigma) for 20 min at room temperature |

| c‐erbB‐2 (P) | Nichirei (Tokyo, Japan) | 1:200 | MW 95°C for 15 min in 10 mM sodium citrate (pH 6) | |

| Phosphotyrosine (M) | 4G10 | Upstate (Lake Placid, NY) | 1:100 | Incubate at 95°C for 40 min in 10 mM sodium citrate (pH 6) with 0.1% Tween 40 |

| Estrogen receptor (M) | 1D5 | Dakocytomation | 1:100 | Autoclave for 15 min in high PH antigen retrieval solution |

| Progesterone receptor (M) | PgR636 | Dakocytomation | 1:100 | Autoclave for 15 min in high PH antigen retrieval solution |

EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; M, monoclonal antibody; P, polyclonal antibody; MW, microwave.

After antigen retrieval for the detection of CD34, KIT, EGFR, c‐erbB‐2, phosphotyrosine, ER and PgR or without antigen retrieval procedure for vimentin, S‐100 and α‐SMA, tissue sections were incubated in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 30 min, reacted with the primary antibody for 1–3 h, incubated with the dextran polymer reagent conjugated with peroxidase and secondary antibody (envision+, Dakocytomation) for 1 h, and subsequently reacted with 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride‐hydrogen peroxide as a chromogen.

Vimentin, S‐100, α‐SMA, and CD34 were judged as expressed if the cytoplasm of tumor cells was moderately to strongly stained in 10% or more of tumor cells.

The KIT expression level was scored as 1+ if the cytoplasm was discretely and weakly to moderately stained and as 2+ if the cytoplasm was strongly stained with or without membrane staining in 10% or more of the constituent carcinoma cells. If no staining was observed, or if staining was observed in less than 10% of the constituent carcinoma cells, a score of 0 was given. Cases with a score of 2+ were judged as overexpression.

The levels of EGFR and c‐erbB‐2 expressions were scored as 2+ and 3+ if the entire circumference of the cell membrane was weakly or moderately stained and strongly stained, respectively, in 10% or more of the constituent carcinoma cells. A score of 1+ was given if incomplete membrane staining was observed in 10% or more of the carcinoma cells, and the score of 0 was given if there was membrane staining in less than 10% of constituent cells or no membrane staining. In SpCC and MPC, the EGFR was also positive in the cytoplasm, and discrete and weak staining, moderate staining, and strong staining of the cytoplasm and/or membrane in 10% or more of the carcinoma cells were scored as 1+, 2+, and 3+. Cases with a score of 2+ or 3+ were judged as overexpression.

Tyrosine phosphorylation was judged to be present if 10% or more of cancer cells showed cytoplasmic staining regardless of whether or not there was membrane staining.

As a positive control for the expressions of KIT and vimentin, a case of GIST was used. A stomach cancer with EGFR gene amplification (> 10‐fold per haploid) and another case of stomach cancer with c‐erbB‐2 gene amplification (> 10‐fold per haploid), detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization, were used as positive controls of EGFR and c‐erbB‐2 overexpression, respectively. For the internal control of S‐100, α‐SMA, and CD34, peripheral nerve, smooth muscle, and endothelial cells were used, respectively. As negative controls, sections without loading the primary antibody were used in each assay.

In the previous study, intra‐ and interobserver agreement levels were almost perfect or, at least, substantial for immunohistochemical results of KIT, EGFR, and c‐erbB‐2 overexpression.( 3 ) The evaluation of immunohistochemical results was given independently by two observers (Hitoshi Tsuda and Yoichi Tani). When there was disagreement in the judgment, consensus was acquired by using a discussion microscope.

Statistical analysis. Statistical differences were analyzed by the chi‐square test or Fisher's exact test.

Results

Expression of myoepithelial markers. Vimentin, S‐100 protein, and α‐SMA were expressed in 28 (88%), 22 (69%), and 15 (47%) of the 32 cases of the undifferentiated types. Vimentin was expressed in 92% (11 of 12) of IDC with a large central acellular zone, 70% (7 of 10) of AMC, and all seven MPC and all three SpCC. The expressions of α‐SMA and S‐100 were also frequent in IDC with a large central acellular zone (50 and 75%), AMC (40 and 60%), MPC (29 and 71%), and SpCC (100 and 100%). In contrast, of 37 cases of the relatively differentiated types, vimentin was expressed in only seven (19%) (P < 0.0001), and α‐SMA and S‐100 were expressed in only one (3%) and one (3%), respectively (P < 0.0001). In six cases of DCIS, two, one, and zero cases showed expression of vimentin, S‐100, and α‐SMA, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation of histological type, KIT, EGFR, and c‐erbB‐2 overexpressions with expression of markers of myoepithelial differentiation in breast carcinomas

| No. cases (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Vimentin | P | S‐100 | P | α‐SMA | P | |

| A. Histological type | |||||||

| Undifferentiated | 32 | 28 (88) | < 0.0001 | 22 (69) | < 0.0001 | 15 (47) | < 0.0001 |

| Relatively differentiated | 36 | 7 (19) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | |||

| Ductal carcinoma in situ | 6 | 2 (33) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) | |||

| B. KIT overexpression | |||||||

| 2+ | 13 | 12 (92) | 0.0006 | 8 (62) | 0.02 | 5 (38) | NS |

| 0 or 1+ | 62 | 25 (40) | 16 (26) | 11 (17) | |||

| C. EGFR overexpression | |||||||

| 2+, 3+ | 30 | 29 (97) | < 0.0001 | 23 (77) | < 0.0001 | 15 (50) | < 0.0001 |

| 0, 1+ | 45 | 8 (18) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | |||

| D. c‐erbB‐2 overexpression | |||||||

| 2+, 3+ | 9 | 3 (33) | NS | 2 (22) | NS | 1 (11) | NS |

| 0, 1+ | 66 | 34 (52) | 22 (33) | 15 (23) | |||

| Total | 75 | 37 | 24 | 16 | |||

EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; NS, not significant.

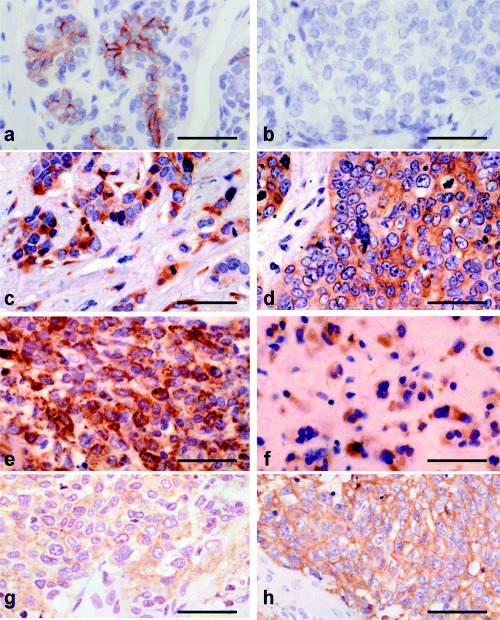

KIT overexpression. KIT was weakly positive in the non‐neoplastic mammary glandular epithelial cells. The staining of KIT 2+ cancer cells was stronger than that of normal mammary glands, but the staining of KIT 1+ was similar to or weaker than that of normal glands (Fig. 2a). KIT overexpression was detected in 13 cases (17%) (Fig. 2b–f). The cytoplasm and membrane staining of the KIT in the control GIST case was categorized as score 2+. In 32 cases of the undifferentiated types, 11 (34%) showed KIT overexpression, whereas, in 37 cases of the relatively differentiated types, only one (3%) showed KIT overexpression (P < 0.0001) (Table 3). In the undifferentiated types, the incidences of KIT overexpression were 42% (5 of 12) of IDC with a large central acellular zone, 20% (2 of 10) of AMC, 57% (4 of 7) of MPC, and 0% (0 of 3) of SpCC. In the relatively differentiated types, KIT overexpression was detected in 4% (1 of 28) of IDC‐NOS, 0% (0 of 6) of ILC, and 0% (0 of 3) of mucinous carcinoma (Table 3). In six cases of DCIS, one (17%) of comedo type showed KIT overexpression.

Figure 2.

Overexpressions of KIT and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in breast carcinomas. (a) Normal mammary gland and cases of; (b) invasive ductal carcinoma‐not otherwise specified (IDC‐NOS), solid‐tubular subtype, nuclear grade 2; (c) IDC with a large central acellular zone; (d) atypical medullary carcinoma (AMC); (e) spindle‐cell carcinoma; and (f) matrix‐producing carcinoma. The scores of KIT expression were 2+ in these four cases in (c–f), which was slightly stronger than (a). KIT expression was negative in (b). (g) IDC with a large central acellular zone and (h) AMC. The score of EGFR was 2+ for (g) and 3+ for (h). Bar 0.1 mm, immunoperoxidase stain.

Table 3.

Incidence of KIT, EGFR, and c‐erbB‐2 overexpressions in various histological types of breast carcinoma

| Histological type | No. cases (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | KIT overexpression | EGFR overexpression | c‐erbB‐2 overexpression | |

| A. Undifferentiated types | ||||

| IDC with a large central acellular zone | 12 | 5 (42) | 11 (92) | 0 (0) |

| Atypical medullary carcinoma | 10 | 2 (20) | 7 (70) | 3 (30) |

| Matrix‐producing carcinoma | 7 | 4 (57) | 7 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Spindle‐cell carcinoma | 3 | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Subtotal | 32 | 11 (34) | 28 (88) | 3 (9) |

| B. Relatively differentiated types | ||||

| IDC‐NOS | 28 | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 2 (7) |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 6 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Mucinous carcinoma | 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) |

| Subtotal | 37 | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 3 (8) |

| C. Ductal carcinoma in situ | 6 | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 3 (50) |

| Total | 75 | 13 (17) | 30 (40) | 9 (12) |

EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; IDC, invasive ductal carcinoma; IDC‐NOS, IDC‐not otherwise specified.

In view of nuclear grade of invasive carcinomas, the KIT was overexpressed in zero (0%), three (13%), and nine (24%) of cases of nuclear grades 1, 2, and 3, respectively (P = 0.0009).

The incidences of expressions of vimentin and S‐100 protein were 92% (12 of 13) and 62% (8 of 13) in the KIT‐overexpressing cases, but these were only 40% (25 of 62) and 26% (16 of 62) in KIT‐non‐overexpressing cases, respectively (P = 0.0006 and P = 0.02, respectively) (Table 2). The expression of CD34 was detected in only four cases (5%). CD34 expression was not significantly correlated with KIT overexpression, but KIT was positive in two of four CD34‐positive cases.

EGFR overexpression. EGFR showed weak cytoplasmic staining in the myoepithelial cells in non‐neoplastic mammary glands. EGFR overexpression was detected in 30 cases (40%) (Fig. 2g–h). The staining of the EGFR in the control stomach cancer case was categorized as 3+. The incidence of EGFR overexpression was 88% (28 of 32) in the undifferentiated types: 92% (11 of 12) of IDC with a large central acellular zone, 70% (7 of 10) of AMC, 100% (7 of 7) of MPC, and 100% (3 of 3) of SpCC. In IDCs with a large central acellular zone, SpCC and MPC, the EGFR was also positive in the cytoplasm. In contrast, EGFR overexpression was rare (3%, 1 of 37) in the relatively differentiated types: 4% (1 of 28) of IDC‐NOS, and 0% each of ILC and mucinous carcinoma (Table 3). In 6 cases of DCIS, one (17%) of comedo type showed EGFR overexpression. EGFR overexpression was detected in 0 (0%), 2 (8%), and 27 (71%) of the invasive carcinomas of nuclear grades 1, 2, and 3, respectively (P < 0.0001).

A strong correlation was seen between the expression of mesenchymal markers and EGFR‐overexpression. The incidences of expressions of vimentin, S‐100 protein, and α‐SMA were 97% (29 of 30), 77% (23 of 30), and 50% (15 of 30) in the EGFR‐overexpressing cases, but these were only 18% (8 of 45), 2% (1 of 45), and 2% (1 of 45) in EGFR‐non‐overexpressing cases, respectively (P < 0.0001, each) (Table 2,C). Although CD34 expression was not significantly correlated with EGFR, all four CD34‐positive cases showed EGFR overexpression.

C‐erbB‐2 overexpression. The c‐erbB‐2 showed weak cytoplasmic staining in the luminal cells in non‐neoplastic mammary glands. The c‐erbB‐2 was overexpressed in 9 cases (12%). The staining of the c‐erbB‐2 in the control stomach cancer case was categorized as 3+. In 32 cases of the undifferentiated types comprising IDC with a large central acellular zone, AMC, MPC, and SpCC, the c‐erbB‐2 was overexpressed in only 3 (9%). In 37 cases of the relatively differentiated types, the c‐erbB‐2 was overexpressed in 3 (8%) (Table 3). In 6 cases of DCIS, three cases (50%), two of comedo type and one of cribriform type, showed c‐erbB‐2 overexpression. C‐erbB‐2 overexpression was detected in 0 (0%), 2 (9%), and 4 (11%) of nuclear grades 1, 2, and 3 invasive carcinomas, respectively.

In contrast to the KIT or EGFR, the expression of vimentin, S‐100, and α‐SMA tended to be more frequent in cases without c‐erbB‐2 overexpression than in those with c‐erbB‐2 overexpression, although the difference was not statistically significant (Table 2, D). Any of four CD34‐positive cases did not show c‐erbB‐2 overexpression.

Correlation between KIT, EGFR, and c‐erbB‐2. Of the 13 cases overexpressing the KIT, 11 (85%) co‐overexpressed the EGFR. In contrast, of the 62 cases that did not show KIT overexpression, only 19 (31%) overexpressed EGFR (Table 4). There was a correlation between KIT overexpression and EGFR overexpression (P < 0.0001). C‐erbB‐2 overexpression was detected in 15% (2 of 13) of KIT‐overexpressing cases, 11% (7 of 62) of KIT‐non‐overexpressing cases, 10% (3 of 30) of EGFR‐overexpressing cases, and 13% (6 of 45) of EGFR‐non‐overexpressing cases. There was no correlation between c‐erbB‐2 overexpression and KIT or EGFR overexpression (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation of KIT overexpression with EGFR overexpression and with c‐erbB‐2 overexpression in breast carcinomas

| No. cases (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | EGFR overexpression | P‐value | c‐erbB‐2 overexpression | P‐value | |

| KIT expression | |||||

| 2+ | 13 | 11 (85) | < 0.0001 | 2 (15) | NS |

| 0 or 1+ | 62 | 19 (31) | 7 (11) | ||

| Total | 75 | 30 (40) | 9 (12) | ||

EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor.

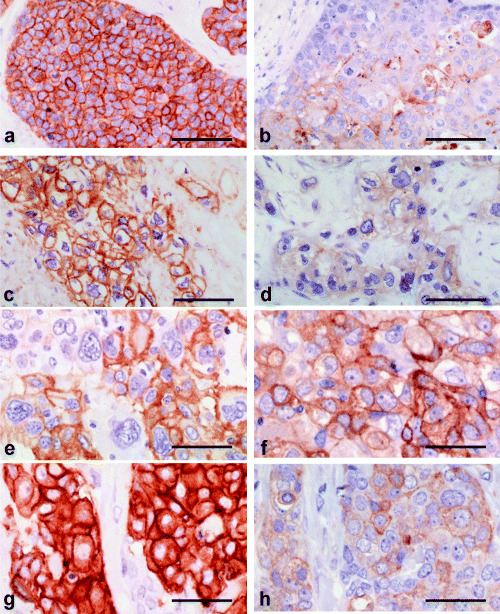

Tyrosine phosphorylation. Tyrosine phosphorylation was detected in 22 (38%) of 58 carcinomas examined: 68% (13 of 19) in the undifferentiated types and 24% (8 of 34) in the relatively differentiated types (Fig. 3a–h). Phosphotyrosine was frequently detected in AMC (7 of 9, 78%) and IDC with a large central acellular zone (6 of 9, 67%). A case of MPC was negative, and no SpCC was examined. In contrast, tyrosine phosphorylation was less frequent in ILC (20%, 1 of 5), IDC‐NOS (27%, 7 of 26), and mucinous carcinoma (0%, 0 of 3). In six cases of DCIS, one (17%) showed tyrosine phosphorylation. In view of nuclear grade in invasive carcinomas, phosphorylation was detected in 14% (1 of 7), 24% (5 of 21), and 63% (15 of 24) of nuclear grades 1, 2, and 3 cases, respectively (P = 0.098).

Figure 3.

The status of KIT, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), c‐erbB‐2, and tyrosine phosphorylation in breast carcinomas. (a,b) A case of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) with both (a) KIT expression (2+) and (b) tyrosine phosphorylation. (c,d) A case of invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) with a large central acellular zone with (c) EGFR overexpression or (d) tyrosine phosphorylation. (e,f) A case of atypical medullary carcinoma with (e) EGFR overexpression (2+) and (f) tyrosine phosphorylation. (g,h) A case of IDC‐not otherwise specified, solid‐tubular subtype with (g) c‐erbB‐2 overexpression (3+) and (h) tyrosine phosphorylation. bar 0.1 mm. Immunoperoxidase stain.

Tyrosine phosphorylation was correlated with EGFR overexpression (P = 0.0055) but did not show correlation with KIT overexpression (P = 0.12) or c‐erbB‐2 overexpression (P = 0.070) (Table 5). When KIT, EGFR, and c‐erbB‐2 were combined, tyrosine phosphorylation was detected in 67% (16 of 24) of KIT‐overexpressing, EGFR‐overexpressing and/or c‐erbB‐2‐overexpressing breast carcinomas, but in only 18% (6 of 34) of the cases without these findings (P = 0.0002).

Table 5.

Correlation of KIT, EGFR, and c‐erbB‐2 overexpressions with tyrosine phosphorylation status, detected by IHC, in breast carcinomas

| Tyrosine phosphorylation | No. cases (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Positive | P‐value | |

| KIT overexpression | |||

| Positive | 8 | 5 (63) | 0.12 |

| Negative | 50 | 17 (34) | |

| EGFR overexpression | |||

| Positive | 16 | 11 (69) | 0.0055 |

| Negative | 42 | 11 (26) | |

| c‐erbB‐2 overexpression | |||

| Positive | 9 | 6 (67) | 0.070 |

| Negative | 49 | 16 (33) | |

| Either KIT/EGFR/c‐erbB‐2 overexpression | |||

| Positive | 24 | 16 (67) | 0.0002 |

| Negative | 34 | 6 (18) | |

| Total | 58 | 22 | |

EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor.

Correlation of hormone receptor status with KIT, EGFR, c‐erbB‐2 and tyrosine phosphorylation. In 67 breast cancer cases, ER and PgR were expressed in 41 (61%) and 39 (58%), respectively. The incidences of ER and PgR expressions were detected in only three (13%) and four (17%) of 24 cases of the undifferentiated type, but they were detected in 34 (92%) and 30 (88%) of 37 cases of the relatively differentiated type and in four (67%) and five (83%) of six cases of DCIS, respectively.

ER was positive in 40 (71%) of 56 cases without KIT overexpression, but was positive in only one (9%) of 11 cases with KIT overexpression (P = 0.0003). PgR was positive in 38 (68%) of 56 cases without KIT overexpression, but was positive in only one (9%) of 11 cases with KIT overexpression (P = 0.0008).

ER was positive in 41 (91%) of 45 cases without EGFR overexpression, but was negative in all 22 cases with EGFR overexpression (P < 0.0001). PgR was positive in 36 (80%) of 45 cases without EGFR overexpression, but was positive in only three (14%) of 22 cases with EGFR overexpression (P < 0.0001).

Discussion

In the present study, the putative undifferentiated‐type breast carcinomas, that is, IDC with a large central acellular zone, AMC, MPC, and SpCC, demonstrated common molecular changes that differed form those in the relatively differentiated‐type breast carcinomas. Most cases of the undifferentiated‐type breast carcinomas expressed vimentin, S‐100, and/or α‐SMA and therefore appeared to show bidirectional differentiation toward luminal epithelial and myoepithelial cells, whereas most cases of the relatively differentiated‐type breast carcinomas only infrequently expressed these myoepithlial markers. It was reasonable to consider that the undifferentiated‐type breast carcinomas had mammary epithelial stem cell‐like features, deduced from their similarity in immunophenotype, although stem cells in breast epithelium are still in dispute.

Conceptually, myoepithelial carcinoma is applied to the malignant neoplasm unidirectionally differentiating toward myoepithelial cells. However, undifferentiated carcinomas of stem cell‐like features show bidirectional differentiation. In the former group, constituent carcinoma cells histologically show spindle shape, but in the latter, constituent carcinoma cells show various morphology among cases ranging from poorly differentiated epithelial features to anaplastic spindle cell features.

In addition, we found that the overexpression of KIT and/or EGFR was frequent in these four undifferentiated‐type breast carcinomas. KIT overexpression also frequently concurred with EGFR overexpression in these carcinoma types. In contrast, KIT and/or EGFR overexpressions were infrequent in the relatively differentiated‐type breast carcinomas. Interestingly, both KIT and EGFR overexpressions strongly correlated with the absence of ER or PgR expression. Therefore, both KIT and EGFR overexpressions were considered to be characteristic markers for the undifferentiated carcinoma types. In addition, EGFR has been claimed to be immunohistochemically positive in the myoepithelial cells in non‐neoplastic condition, and, in contrast, c‐erbB‐2 is positive in the luminal cells.

It was already shown that both the EGFR and c‐erbB‐2 were overexpressed mostly in high‐grade (Grade 3) IDC.( 8 , 9 , 18 , 19 ) We found that c‐erbB‐2 overexpression was relatively infrequent in the undifferentiated‐type breast carcinomas except for AMC. EGFR overexpression and c‐erbB‐2 overexpression appeared to be independent events in resected breast cancer cases. From these findings, the degree of differentiation should exist even among the cases of histologically Grade 3 carcinomas: The least differentiated subgroup in Grade 3 carcinomas that still preserves the potential of stem cell‐like bidirectional differentiation frequently showed KIT and/or EGFR overexpressions. In contrast, the relatively differentiated subgroup in Grade 3 carcinomas, so as to commit unidirectional maturation as if transit amplifying cells or progenitor cells, tended to lack KIT or EGFR overexpression. C‐erbB‐2 overexpression was not correlated with these subgroups.

The activation of the KIT, EGFR, and c‐erbB‐2 is accompanied with tyrosine phosphorylation. In the present study, the status of tyrosine phosphorylation, detected by IHC, had a significant correlation with EGFR overexpression and with either overexpression the KIT, EGFR, or c‐erbB‐2 oncoprotein. These results suggested that overexpressions of KIT, EGFR, and c‐erbB‐2 were frequently phosphorylated and would be biologically meaningful in breast carcinoma cases. There should be dozens of phosphorylated growth factor receptors other than the KIT, EGFR, and c‐erbB‐2. Nonetheless, immunohistochemical evaluation of tyrosine phosphorylation status might be helpful to predict the status of activation of these tyrosine‐kinase‐receptor type oncoproteins.

Monoclonal antibodies or tyrosine kinase inhibitors to specific oncoproteins have been developed and are now routinely used as novel anticancer drugs. Trastuzumab, a humanized antic‐erbB‐2 antibody, is effective for patients with c‐erbB‐2‐overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. ( 20 ) The clinical efficacy of the anti‐EGFR antibody and the EGFR tyrosine‐kinase inhibitor has also been reported for patients with colorectal cancers and non‐small cell lung cancers.( 7 , 21 ) Recently, imatinib (gleevec), a tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeted to tyrosine‐phosphorylated BCR‐ABL chimeric gene products and the KIT oncoprotein, has been found to be effective in the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia and GIST.( 22 , 23 )

The incidence of the undifferentiated‐type breast carcinomas showing bidirectional differentiation could be estimated to be approximately 5 to 10% of all breast cancer cases: the percentages of IDC with large central acellular zone, AMC, MPC, and SpCC were reported to be 2–3, 5–7, 0.2 and 0.2%, respectively.( 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ) If the activations of KIT and EGFR are involved in carcinoma cell growth in these histological types, inhibition of these oncoproteins would contribute to the regression in tumor mass in vivo. It might be worth investigating if therapies against the active KIT and/or EGFR are effective in these four histological types and/or in breast carcinomas with KIT and/or EGFR overexpressions. The immunophenotyping of breast carcinoma based on KIT, EGFR, c‐erbB‐2, and myoepithelial markers might be of clinical value in the near future.

In summary, KIT and/or EGFR overexpressions, detected by IHC, were frequent in the undifferentiated‐type breast carcinomas mainly composed of cells with bidirectional differentiation toward luminal epithelial and myoepithelial cells, or those of mammary epithelial stem‐cell features. KIT and EGFR overexpressions frequently concurred, but they tended to be independent of c‐erbB‐2 overexpression. The examination of KIT and EGFR overexpressions could be meaningful for understanding cellular origin and biological behavior of breast cancers, especially high‐grade breast carcinomas, and of clinical importance for individualizing therapeutic strategy.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grants‐in‐aid from Nippon Roche (presently Chugai Pharmaceutical), Taiho Pharmaceutical, and Astrazeneca.

References

- 1. Smalley M, Ashworth A. Stem cells and breast cancer: a field in transit. Nature Rev 2003; 3: 832–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pechoux C, Gudjonsson T, Ronnov‐Jessen L, Bissel MJ, Petersen OW. Human mammary luminal epithelial cells contain progenitors to myoepithelial cells. Dev Biol 1999; 206: 88–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tsuda H, Morita D, Kimura M et al. Correlation of KIT and EGFR overexpression with invasive ductal breast carcinoma of the solid‐tubular subtype, nuclear grade 3, and mesenchymal or myoepithelial differentiation. Cancer Sci 2005; 96: 48–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Qiu FH, Ray P, Brown K et al. Primary structure of c‐kit: Relationship with the CSF‐1/PDGF receptor kinase family‐oncogene activation of v‐kit involves deletion of extracellular domain and C terminus. EMBO J 1998; 7: 1003–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yarden Y, Kuang WJ, Yang‐Feng T et al. Human protooncogene c‐kit: a new cell surface receptor tyrosine kinas for an unidentified ligand. EMBO J 1987; 6: 3341–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y et al. Gain‐of‐function mutations of c‐kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science 1998; 279: 577–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baselga J. The EGFR as a target for anticancer therapy – focus on cetuximab. Eur J Cancer 2001; 37: S16–S22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Walker RA, Dearing SJ. Expression of epidermal growth factor receptor mRNA and protein in primary breast carcinomas. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1999; 53: 167–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tsutsui S, Ohno S, Murakami S, Hachitanda Y, Oda S. Prognostic value of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and its relationship to the estrogen receptor status in 1029 patients with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2002; 71: 67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rosen PP. Breast Pathology. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott‐Raven, 1997;. 355–95. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ridolfi RL, Rosen PP, Port A, Kinne D, Miké V. Medullary carcinoma of the breast. A clinicopathologic study with 10 year follow‐up. Cancer 1977; 40: 1365–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tsuda H, Takarabe T, Hasegawa F, Fukutomi T, Hirohashi S. Large central acellular zones indicating myoepithelial tumor differentiation in high‐grade invasive ductal carcinomas as markers of predisposition to lung and brain metastases. Am J Surg Pathol 2000; 24: 197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wargotz ES, Deos PH, Norris HJ. Metaplastic carcinomas of the breast. II. Spindle cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol 1989; 20: 732–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wargotz ES, Norris HJ. Metaplastic carcinomas of the breast. I. Matrix‐producing carcinoma. Hum Pathol 1989; 20: 628–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ashida A, Fukutomi T, Ushijima T, Tsuda H, Akashi‐Tanaka S, Nanasawa T. Atypical medullary carcinoma of the breast with cartilaginous metaplasia in a patient with a BRCA1 germline mutation. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2000; 30: 30–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hama Y, Tsuda H, Sato K, Hiraide H, Mochizuki H, Kusano S. Invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast with a large central acellular zone associated with matrix‐producing carcinoma. Tumori 2004; 90: 498–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Japanese Breast Cancer Society. General Rules for Clinical and Pathological Recording of Breast Cancer, 15th edn. Kanehara Shuppan, Tokyo, 2004. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 18. Revillion F, Bonneterre J, Peyrat JP. ERBB2 oncogene in human breast cancer and its clinical significance. Eur J Cancer 1998; 4: 791–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hayes DF, Thor AD. c‐erbB‐2 in breast cancer: development of a clinically useful marker. Semin Oncol 2002; 29: 231–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Slamon DJ, Leyland‐Jones B, Shak S et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 783–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ranson M, Hammond LA, Ferry D et al. ZD1839, a selective oral epidermal growth factor receptor‐tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is well tolerated and active in patients with solid, malignant tumors: Results of a phase I trial. J Clin Oncol 2002; 20: 2240–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Druker BJ, Talpaz M, Resta DJ et al. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the Bcr‐Abl tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1031–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Demetri GD, Von Mehren M, Blanke CD et al. Efficacy and safety of imatinib mesylate in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 472–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]