Abstract

Sphingolipids are putative intracellular signal mediators in cell differentiation, growth inhibition, and apoptosis. Sphingosine, sphinganine, and phytosphingosine are structural analogs of sphingolipids and are classified as long‐chain sphingoid bases. Sphingosine and sphinganine are known to play important roles in apoptosis. In the present study, we examined the phytosphingosine‐induced apoptosis mechanism, focusing on mitochondria in human T‐cell lymphoma Jurkat cells. Phytosphingosine significantly induced chromatin DNA fragmentation, which is a hallmark of apoptosis. Enzymatic activity measurements of caspases revealed that caspase‐3 and caspase‐9 are activated in phytosphingosine‐induced apoptosis, but there is little activation of caspase‐8 suggesting that phytosphingosine influences mitochondrial functions. In agreement with this hypothesis, a decrease in ΔΨm and the release of cytochrome c to the cytosol were observed upon phytosphingosine treatment. Furthermore, overexpression of mitochondria‐localized anti‐apoptotic protein Bcl‐2 prevented phytosphingosine apoptotic stimuli. Western blot assays revealed that phytosphingosine decreases phosphorylated Akt and p70S6k. Dephosphorylation of Akt was partially inhibited by protein phosphatase inhibitor OA and OA attenuated phytosphingosine‐induced apoptosis. Moreover, using a cell‐free system, phytosphingosine directly reduced ΔΨm. These results indicate that phytosphingosine perturbs mitochondria both directly and indirectly to induce apoptosis. (Cancer Sci 2005; 96: 83–92)

Abbreviations:

- ΔΨm

mitochondrial membrane potential

- OA

Okadaic acid

- PT

permeability transition

- AIF

apoptotic inducing factor

- PKC

protein kinase C

- JNK

c‐jun N‐terminal protein kinase

- SAPK

stress‐activated protein kinases

- ERK

extracellular signal‐regulated kinase

- FTY720

2‐amino‐2‐[2‐(4‐octylphenyl) ethyl]‐1,3‐propanediol hydrochloride

- MTT

3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

- PI

propidium iodide

- DiOC6 (3)

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- 3,3"‐dihexyloxacarbocyanide

iodide

- PMSF

phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride

- CCCP

carbonyl cyanide m‐chlorophenyl hydrazone

- PP

protein phosphatase, PH, pleckstrin homology

- PI(3,4,5)P3

Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5‐triphosphate

- PI(3,4)P2

phosphatidylinositol 3,4‐diphosphate

- PDK1

Phosphoinositide‐dependent kinase 1

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin.

Organelle mitochondria play an important role in the induction of apoptosis machinery. Upon apoptosis, mitochondria undergo PT with the opening of an apoptosis‐related pore called a mitochondrial PT pore complex, which is the basis for mitochondria‐mediated apoptosis. (1) PT pore opening results in a reduction of ΔΨm and the release of AIF, Smac/DIABLO, and cytochrome c to the cytosol. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 Released AIF directly affects nuclei and triggers chromatin condensation. (4) Cytochrome c binds to Apaf‐1 and then activates initiator caspase, caspase‐9. Activated caspase‐9 in turn activates the effector caspase, caspase‐3, and activated caspase‐3 cleaves a variety of substrates to execute apoptosis by means of chromatin DNA fragmentation, morphological changes, and a loss of cell volume. 7 , 8 Smac/DIABLO promotes this cytochrome c‐dependent caspase activation by binding to the inhibitor of apoptotic proteins, IAP. 5 , 6 The anti‐apoptotic Bcl‐2 family proteins, Bcl‐2 and Bcl‐xL, inhibit apoptosis by preventing opening of the PT pore. (1) Apoptotic signals are transmitted by many pathways to mitochondria. One such pathway induced by most anticancer drugs involves direct or indirect induction of PT by affecting mitochondria. 9 , 10 Another pathway involves inhibition of Bcl‐2 and Bcl‐xL anti‐apoptotic effects by specific binding with the pro‐apoptotic Bcl‐2 family protein (e.g. Bax, Bid, and Bad) migrating from the cytosol. In p53‐mediated apoptosis, cytosolic Bax is redistributed to the mitochondria to induce PT. (2) In Fas/CD95‐mediated apoptosis, caspase‐8 is activated, followed by cleavage of Bid. Cleaved (activated) Bid translocates from the cytosol to the mitochondria and executes the postmitochondrial apoptotic pathway. (11) In the depletion of survival factor‐mediated apoptosis, the PI 3‐kinase pathway is attenuated. Ser/Thr kinase Akt, also known as protein kinase B, is the major mediator of the survival signal in the PI 3‐kinase pathway that protects cells from undergoing apoptosis. (12) Pro‐apoptotic Bcl‐2 family Bad is usually phosphorylated by Akt; it is thereby captured by the 14‐3‐3 protein and finally degraded. Once Akt kinase activity becomes attenuated, dephosphorylation of Bad occurs and Bad localizes to the mitochondria, forming the postmitochondrial apoptotic pathway. (13) Moreover, Akt itself prevents formation of the pre‐ or post‐mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Akt prevents PT by affecting the PT pore complex protein hexokinase. 14 , 15 Akt also inhibits caspase‐9 activity by phosphorylating caspase‐9. (16)

Sphingomyelin and its metabolites, sphingolipids, are known to be involved in diverse types of signal transduction, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. The sphingolipids ceramide and sphingosine induce apoptosis in a variety of cells. 17 , 18 , 19 Ceramide is generated from sphingomyelin upon diverse apoptotic stimuli and transfers the death signal, which is the so‐called second messenger. (17) Ceramide induces apoptosis by inhibiting a variety of pro‐growth signal kinases, including Akt and PKC, with direct activation of protein phosphatases. (20) In contrast, ceramide also activates pro‐apoptosis kinases, such as JNK and so‐called SAPK. (20) Ceramide is further metabolized to sphingosine. Sphingosine and its analog sphinganine are also mediators of apoptosis in a variety of cells. Like ceramide, sphingosine and sphinganine inhibit PKC 21 , 22 and Akt. (18) Recent reports have revealed that sphingosine and its derivatives, sphinganine and phytosphingosine, dephosphorylate pro‐growth signal kinase, ERK1, and ERK2 with involvement of PKC. (23) Moreover, sphingosine inhibits RNA primers and DNA primers, but not DNA polymerases, to induce cell death. 19 , 24 However, the study of another sphingosine analog, phytosphingosine, has recently begun.

In the present study, we therefore examined the precise mechanism of phytosphingosine‐mediated apoptosis in T‐cell lymphoma Jurkat cells in comparison with sphingosine. It was found that phytosphingosine, almost identically to sphingosine, significantly induces apoptosis in Jurkat cells. We also describe how mitochondria is involved in phytosphingosine‐induced apoptosis.

Materials and methods

Cells. The human lymphoid T‐cell line, Jurkat, stably transfected with a human bcl‐2 expression plasmid (bcl‐2) or neomycin resistance plasmid (neo) was provided by Dr T. Miyashita of the National Research Institute for Child Health and Development (Tokyo, Japan).

Drugs. Phytosphingosine and sphingosine were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA) and dissolved in methanol (10 mM). FTY720 was synthesized and supplied in powder form by Taito (Tokyo, Japan) in cooperation with Mitsubishi Pharma (Osaka, Japan). FTY720 was dissolved in saline (1 mM).

Antibodies. Anti‐caspase‐8 antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Anti‐cytochrome c was purchased from PharMingen (San Diego, CA, USA). Anti‐phosphorylated Akt, Akt, phosphorylated p70S6k, p70S6k, phosphorylated SAPK/JNK and SAPK/JNK were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverley, MA, USA).

Medium and cell cultures. Cells were cultured in RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 75 mg/L‐Kanamycin, and maintained at 37°C in a humidified chamber under an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2.

MTT assay. Cells (2 × 104) were incubated with or without drugs in 96‐well flat‐bottomed plates. One hour before the indicated incubation time, 10 µL of 5 mg/mL MTT (Sigma) was added to each well. The plates were centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min, and the supernatants were discarded. Colored formazan in the living cells was developed by adding 100 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide to each well, and the absorbance of each well was measured using a microplate reader at 570 nm. Cell viability is expressed as a percentage of the control absorbance.

Assessment of sub‐G1 cells and cell cycle. Cells (1 × 106) were washed with PBS and suspended in permeabilizing buffer (0.2% Triton‐X 100 in PBS). Thereafter, cells were washed with PBS, resuspended in PBS containing 0.5 mg/mL RNase A and 2 µg/mL PI, and analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, Beckton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA, USA). Data were analyzed using Cell Quest (Beckton Dickinson) and ModFit LT software (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME, USA).

Agarose gel electrophoresis. Apoptosis was determined by DNA fragmentation, which was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Cells (1 × 106) were rinsed once with 10 mM Tris‐HCl buffer (pH 8.7), containing 3 mM MgCl2 and 2 mM 2‐mercaptoethanol and dissolved in 50 mM Tris‐HCl buffer (pH 7.8), containing 10 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium lauryl sarcocinate, and 1 mg/mL proteinase K. After incubation at 50°C for 30 min, RNase A was added at a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL and further incubated at 50°C for 15 min. Lysates were mixed with an equal volume of loading buffer containing TBE buffer (89 mM Tris, pH 8.4, 2.5 mM EDTA, 89 mM boric acid), 20% glycerol, and 0.01% bromophenol blue. Samples were electrophoresed on 1.8% agarose gels in TBE containing 0.5 mg/mL ethidium bromide.

Caspase activity assay. Cells (4 × 106) were lyzed in RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM KCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P‐40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS), and cell lysates were obtained by centrifugation at 10 000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Cell lysates were incubated in 250 µL of caspase buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% Chaps, 10% sucrose, 5 mM dithiothreitol) containing 80 µM substrate, Ac‐DEVD‐MCA (for Caspase‐3), Ac‐IETD‐MCA (for Caspase‐8), or Ac‐LEHD‐MCA (for Caspase‐9). After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, 250 µL of stop solution (0.2 M glycine‐HCl, pH 2.7) was added. The mixture was centrifuged, and the release of 7‐amino‐4‐methyl‐coumarin in the supernatant was measured using the Wallac ARVO 1420 microtiter plate spectrofluorometer (Perkin Elmer Japan, Yokohama, Japan) at excitation and emission wavelengths of 380 and 460 nm, respectively.

Determination of mitochondrial membrane potential in intact cells. Cells (2 × 105) were incubated for 15 min with medium containing 100 nM DiOC6(3) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). After incubation, cells were washed with PBS then resuspended in PBS to examine ΔΨm by flow cytometry.

Preparation of cytosol fraction. Cells (1 × 107) were washed with PBS and suspended in isotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES, 0.3 M mannitol, 0.1 mM Digitonin, 0.1% bovine serum albumin). After incubation on ice for 5 min, supernatant was collected as cytosol fraction with centrifugation at 4°C for 5 min at 15 000 × g. Samples were used immediately or stored at −80°C until immunodetection for cytochrome c.

Preparation of cell lysates. Cells were washed with PBS and placed on ice for 20 min in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris‐HCl, pH 7.5, 1% Nonidet P‐40, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM PMSF, 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1% protease inhibitor mix (Sigma)). Cell lysates were centrifuged at 4°C for 15 min at 15 000 × g. Protein concentrations of the supernatant were determined using the BCA protein assay. Samples were used immediately or stored at −80°C until immunodetection.

Western blots. Cell lysates (15 µg) or cytosol fractions (20 µL) were mixed in the same volume of SDS sample buffer (4% SDS, 125 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 0.02 mg/mL bromophenol blue, 10% 2‐mercaptoethanol) and heated at 100°C for 3 min. Proteins were separated by 12% or 4–20% gradient polyacrylamide gel SDS‐electrophoresis and electrically transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). After blocking the membrane using 3% skimmed milk, caspase‐8, cytochrome c, phosphorylated Akt, Akt, phosphorylated p70S6k, p70S6k, phosphorylated SAPK/JNK, and SAPK/JNK were immunodetected using specific antibodies. Thereafter, horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated anti‐rabbit or ‐mouse IgG was applied as the second antibody, and positive bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Life Science, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Nuclear morphology. Cells (4 × 105) were incubated in dish culture with or without 400 nM OA. After 30 min, 8 µM phytosphingosine was added and further incubated for 4 h. After incubation, 5 µM Hoechst 33342 and 2 µg/mL PI was added and the number of viable, apoptotic cells were counted by fluorescence microscopy.

Determination of isolated mitochondrial membrane potential. Cells (1 × 107) were washed with PBS, suspended in 5 volumes of CFS buffer (220 mM mannitol, 68 mM sucrose, 2 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KH2PO4, 0.5 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM pyruvate, 0.1 mM PMSF, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4), and swollen on ice for 20 min. Cells were disrupted by 10 aspirations through a 22‐gauge needle and centrifuged at 750 × g for 5 min at 4°C to remove the nuclei. The supernatant was centrifuged again (10 000 × g, 10 min, 4°C) to recover mitochondria. Isolated mitochondria were washed and resuspended in CFS buffer at a concentration of approximately 25 µg mitochondrial protein in 100 µL CFS buffer. After incubation with or without drugs for 30 min at 37°C, the mitochondrial suspensions were further incubated for 15 min with 50 nM DiOC6 (3). ΔΨm was examined by flow cytometry.

Results

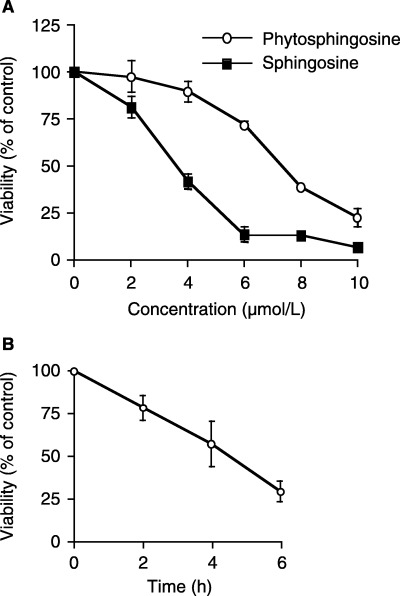

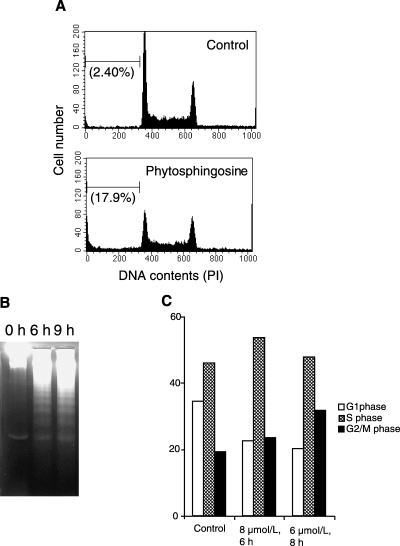

Phytosphingosine‐induced apoptosis and cell‐cycle arrest in Jurkat cells. Sphingosine is known as a potent inducer of apoptosis. 18 , 24 , 25 To estimate the potency of the cellular dysfunction of phytosphingosine, the MTT assay was performed to determine cell viability. Six‐hour treatment with sphingosine significantly reduced the viability of human T‐cell lymphoma Jurkat cells in a dose‐dependent manner (Fig. 1a). Jurkat cells dropped to less than 50% viability percentage when treated with <4 µM of sphingosine. Like sphingosine, phytosphingosine also decreased the viability of Jurkat cells. Phytosphingosine treatment reduced this viability dose‐dependently, and a <8 µM treatment resulted in a loss of viability to less than 50%. Moreover, 8 µM phytosphingosine induced a time‐dependent loss of viability (Fig. 1b), suggesting that phytosphingosine reduced Jurkat cell viability almost identically to sphingosine. Next, the DNA content was confirmed by flow‐cytometric analysis staining with PI. As shown in Fig. 2(a), 6‐h treatment with 8 µM phytosphingosine increased sub‐G1 cells from 2.4 to 17.9%. Moreover, phytosphingosine‐induced DNA fragmentation was further observed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Figure 2(b) shows that 8 µM phytosphingosine treatment fragmented genomic DNA, resulting in a ladder form. Furthermore, we analyzed the percentage of cells in G1‐, S‐, and G2/M‐phase. Six‐hour treatment of 8 µM phytosphingosine decreased the percentage of G1‐phase cells from 34.5 to 22.6% (Fig. 2c). Conversely, the percentages of S‐phase and G2/M‐phase cells increased with treatment of phytosphingosine from 46.0 to 53.6%, and from 19.5 to 23.8%, respectively. Interestingly, 8‐h treatment of 6 µM phytosphingosine increased the percentage of sub‐G1 cells (8.04%) less than the 6‐h treatment of 8 µM phytosphingosine (17.9%), but the percentages of G2/M‐phase cells were significantly increased (Fig. 2c). These results suggest that phytosphingosine, in contrast to sphingosine, induces not only DNA fragmentation but also G2/M cell‐cycle arrest to reduce cell viability.

Figure 1.

Dose‐ and time‐ dependent Jurkat cell viability decreases after treatment with phytosphingosine. Jurkat (neo) cells were incubated for 6 h, with or without drugs, at concentrations ranging from 2 to 10 µM (a), or for the indicated times with or without 8 µM phytosphingosine (b). At the indicated times, the cells were collected and subjected to MTT assay. The results are presented as the percentage of absorbance in untreated cultures. Each bar denotes the standard deviation (n = 4).

Figure 2.

Phytosphingosine‐induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in Jurkat cells. (a) Jurkat (neo) cells were incubated with 0 or 8 µM phytosphingosine for 6 h. At the indicated times, the cells were collected and permeabilized. Cells were then stained with PI, and the DNA contents were determined by flow cytometry. Values in parentheses indicate sub‐G1 cell percentages. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (b) Jurkat (neo) cells were incubated with 8 µM phytosphingosine for 0, 6, and 9 h. At the times indicated, the cells were lyzed and DNA was prepared. DNA fragmentation was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. (c) Jurkat (neo) cells were incubated with or without phytosphingosine for indicated times and doses. Percentage of cells in each cell cycle phase were measured. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Phytosphingosine‐induced mitochondria‐involved caspase activation.

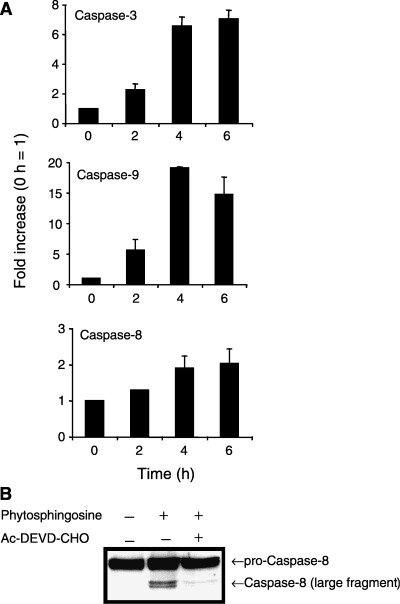

We further determined the mechanism of phytosphingosine‐induced apoptosis. Caspase activation was observed using specific peptide‐substrates for the following: caspase‐3 as the representative for effector caspases; caspase‐8 as the representative of the receptor (Fas/CD95)‐mediated initiator caspases; and caspase‐9 as the representative of the mitochondria‐mediated initiator caspases. Caspase‐3 as well as caspase‐9 was activated after treatment with 8 µM phytosphingosine (Fig. 3a). Caspase‐3 was activated to levels six times those of the control activity after a 6‐h treatment. Caspase‐9 was activated from 2 h and peaked at 18‐fold after a 4‐h treatment. Caspase‐9 was significantly activated earlier than caspase‐3. Most importantly, however, both caspases were activated prior to phytosphingosine‐induced DNA fragmentation (Fig. 2b). Because caspase‐8 was activated during phytosphingosine‐induced apoptosis, however, the activation rate was rather low (1.8‐fold over control levels after a 6‐h treatment). Indeed, caspase‐3 specific inhibitor, Ac‐DEVD‐CHO, prevented phytosphingosine‐induced pro‐caspase‐8 cleavage (Fig. 3b). Moreover, Z‐VAD‐FMK, the broad caspase inhibitor, completely inhibited phytosphingosine‐induced DNA fragmentation (data not shown). These results indicate that phytosphingosine induces caspases downstream from the mitochondria, but not downstream from the receptor (Fas/CD95). Activated caspases further fragmented the DNA.

Figure 3.

Phytosphingosine‐induced caspase activation. (a) Jurkat (neo) cells were incubated with 8 µM phytosphingosine for 0, 2, 4, and 6 h. At the times indicated, cells were lyzed and caspase‐3, caspase‐9, and caspase‐8 activity were determined by specific peptides, Ac‐DEVD‐MCA, Ac‐LEHD‐MCA, and Ac‐IETD‐MCA, respectively. Each bar denotes the standard deviation (n = 3). (b) Jurkat (neo) cells were incubated with or without 20 µM Ac‐DEVD‐CHO for 1 h, thereafter with or without 8 µM phytosphingosine for 4 h. Cells were collected and lyzed. Western blots were performed with antibody for caspase‐8.

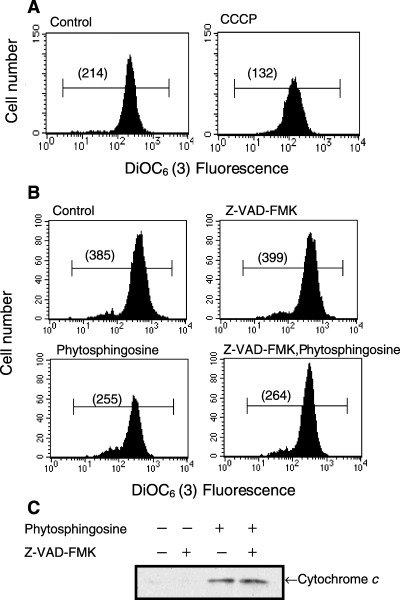

Phytosphingosine reduced mitochondrial ΔΨm and cytochrome c release independently of caspase activation; overexpression of Bcl‐2 prevented phytosphingosine‐mediated apoptosis. Based on the above experiments, phytosphingosine seemed to be involved in mitochondria‐mediated apoptosis. We further attempted to estimate the upstream events of caspase activation. In mitochondria‐mediated apoptosis, ΔΨm was reduced and cytochrome c was released from mitochondria. Thus, we further examined the perturbation of mitochondria during apoptosis by detecting ΔΨm and the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria to the cytosol. For detecting ΔΨm, we used the fluorescent cation DiOC6(3), which can be taken up by cells ΔΨm‐dependently. Figure 4(a) shows a reduction in ΔΨm in response to treatment with protonophore, CCCP. CCCP causes a dissipation of the proton gradient across the mitochondrial membrane. According to Fig. 4(b), 8 µM phytosphingosine began reducing ΔΨm 30 min after treatment. This reduction was quite early, in comparison with caspase activation (<2 h), suggesting that reduction of ΔΨm is an upstream event of caspase activation. In addition, pretreatment with the broad caspase inhibitor Z‐VAD‐FMK did not inhibit the reduction of ΔΨm by phytosphingosine. Moreover, we detected the presence of cytochrome c in the cytosol fraction by Western blot. Figure 4(c) shows that phytosphingosine released cytochrome c from mitochondria to the cytosol. In agreement with the ΔΨm experiment, Z‐VAD‐FMK did not inhibit the release of cytochrome c, indicating that the phytosphingosine‐induced ΔΨm decrease and cytochrome c release were independent of caspase activation. More specifically, ΔΨm reduction and cytochrome c release occur upstream from phytosphingosine‐induced caspase activation.

Figure 4.

Phytosphingosine affected the mitochondria independent of caspases. (a) Jurkat (neo) cells were incubated with or without 5 µM CCCP for 30 min. DiOC6 (3) was added 15 min before the end of the culture period, and ΔΨm was analyzed by flow cytometry. Values in parentheses indicate the median fluorescence intensity. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (b) Jurkat (neo) cells were incubated with or without 50 µM Z‐VAD‐FMK for 30 min, thereafter with or without 8 µM phytosphingosine for 30 min. DiOC6 (3) was added 15 min before the end of the culture period, and ΔΨm was analyzed by flow cytometry. Values in parentheses indicate the median fluorescence intensity. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (c) Jurkat (neo) cells were incubated with or without 50 µM Z‐VAD‐FMK for 30 min, thereafter with or without 8 µM phytosphingosine for 4 h. Cells were collected and cytosol fraction was obtained. Western blots were performed with antibody for cytochrome c.

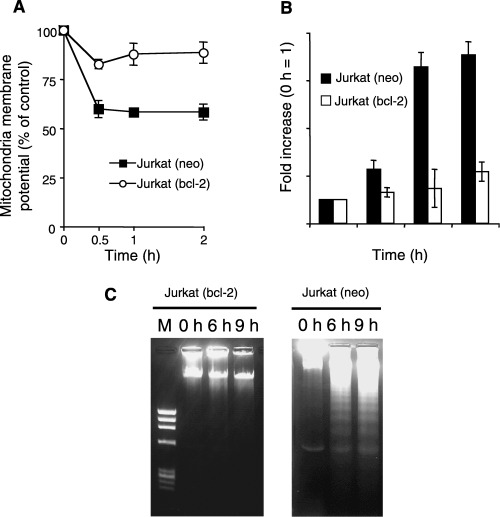

Moreover, overexpression of mitochondria‐localized anti‐apoptotic protein Bcl‐2 left ΔΨm unchanged, even after treatment with phytosphingosine (Fig. 5a). Bcl‐2 overexpression attenuated caspase activation (Fig. 5b) and DNA fragmentation (Fig. 5c), indicating that mitochondrial dysfunction as a result of phytosphingosine treatment is a crucial factor and that this dysfunction must therefore occur upstream from phytosphingosine‐induced apoptotic stimuli.

Figure 5.

Phytosphingosine‐induced apoptosis is blocked by overexpression of Bcl‐2. (a) Jurkat (neo) and Jurkat (bcl‐2) cells were incubated with 8 µM phytosphingosine for 0, 0.5, 1, and 2 h. DiOC6 (3) was added 15 min before the end of the culture period, and ΔΨm was analyzed by flow cytometry. The results are presented as averages of the median fluorescence intensity. Each bar denotes the standard deviation (n = 3). (b) Jurkat (neo) and Jurkat (bcl‐2) cells were incubated with 8 µM phytosphingosine for 0, 2, 4, and 6 h. At the times indicated, cells were lyzed and caspase‐3 activity was determined by specific peptide, Ac‐DEVD‐MCA. Each bar denotes the standard deviation (n = 3). (c) Jurkat (neo) and Jurkat (bcl‐2) cells were incubated with 8 µM phytosphingosine for 0, 6, and 9 h. At the times indicated, the cells were lyzed and DNA was prepared. DNA fragmentation was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

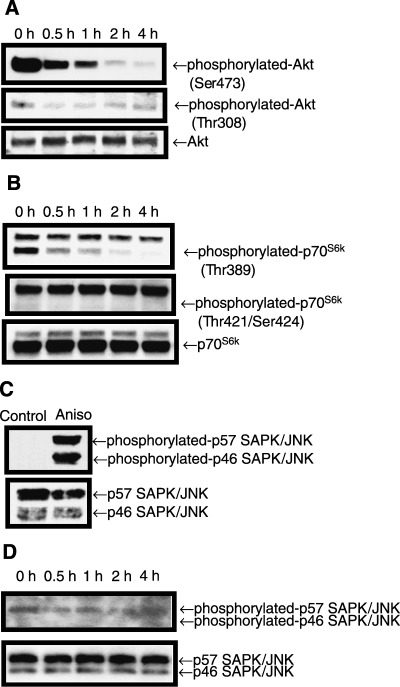

Phytosphingosine dephosphorylated Akt to inhibit pro‐growth signal. We next determined how phytosphingosine reduced ΔΨm. Because sphingosine, a phytosphingosine analog, dephosphorylates Akt, (18) we hypothesized that phytosphingosine might also inactivate the pro‐growth signal pathway, the PI 3‐kinase/Akt pathway. The active form of Akt is dual‐phosphorylated at Ser473 and Thr308 sites. Dual‐phosphorylated active Akt inhibits Bad from translocating to the mitochondria, and also inhibits PT pore‐opening. 12 , 13 , 14 Western blot analysis was performed with phosphorylated site‐specific antibodies. As shown in Fig. 6(a), Ser473 and Thr308 sites of Akt were dual‐phosphorylated without treatment with phytosphingosine (in the steady state). These Akt (Ser473) and Akt (Thr308) phosphorylations were gradually decreased time‐dependently with phytosphingosine treatment. This result indicates that phytosphingosine inactivated Akt. We further examined whether phytosphingosine inactivates a downstream kinase of the PI‐3 kinase/Akt pathway, p70S6k. Figure 6(b) shows that the Thr389 site of p70S6k was dephosphorylated by treatment with phytosphingosine. In contrast to the Thr389 site, phosphorylation of the Thr421/Ser424 site was undetectable. A recent study has revealed that in ceramide‐induced apoptosis, pro‐apoptotic kinase SAPK/JNK is activated. (20) However, phytosphingosine treatment did not alter phosphorylated SAPK/JNK levels in comparison with the positive control (Fig. 6c,d). Overall, phytosphingosine inactivated the PI 3‐kinase/Akt pathway upon apoptosis and caused a progression of apoptotic stimuli.

Figure 6.

Phytosphingosine reduced phosphorylated Akt and p70S6k. Jurkat (neo) cells were incubated with 8 µM phytosphingosine for the indicated times. Cells were collected and lyzed. Western blots were performed with antibodies specific for phosphorylated Akt (Ser473) (Thr308) and Akt (a), phosphorylated p70S6k (Thr389) (Thr421/Ser424), and p70S6k (b), and phosphorylated SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) and SAPK/JNK (d). For positive control of phosphorylated SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Thr185), 1 h incubation with 1 µg/mL anisomysin (Aniso) was used (c). Samples were exposed to films for 30 s, except when detecting phosphorylated SAPK/JNK in (d), which was exposed to film for 5 min.

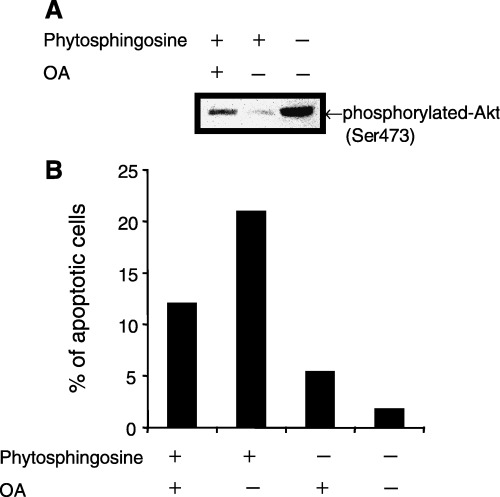

Protein phosphatase inhibitor attenuated phytosphingosine‐induced Akt dephosphorylation. We further attempted to determine how phytosphingosine dephosphorylated Akt and p70S6k. Ser/Thr protein phosphatases, including PP2A, dephosphorylate Akt and the downstream kinase p70S6k. We have previously found that the sphingosine analog drug, FTY720, activates PP2A and dephosphorylates Akt. (26) We therefore investigated whether phytosphingosine‐induced dephosphorylation of Akt is associated with PP2A activity. Cells were incubated in the presence or absence of the PP1 and PP2A inhibitor, OA, for 30 min. Thereafter, phytosphingosine was added and the cells were incubated for an additional 30 min. Western blot analysis was performed with phosphorylated Akt (Ser473) antibody. Incubating with OA did not alter the immunoreactivity of phosphorylated Akt compared to that of untreated cells (data not shown). Incubation of cells with OA partially attenuated phytosphingosine‐induced reduction of phosphorylated Akt (Fig. 7a). These data suggest that PP1‐ or PP2A‐like PP activity is associated with the dephosphorylation effects of phytosphingosine on phosphorylated Akt. Moreover, OA partially inhibited phytosphingosine‐induced apoptosis (Fig. 7b), indicating that dephosphorylation of Akt by phytosphingosine is one factor in the apoptosis mechanism.

Figure 7.

OA attenuated phytosphingosine‐induced Akt phosphorylation and apoptosis. (a) Jurkat (neo) cells were incubated with 400 nM OA for 30 min, thereafter 8 µM phytosphingosine for 1 h. Cells were collected and lyzed. Western blots were performed with antibodies specific for phosphorylated Akt (Ser473). (b) Jurkat (neo) cells were incubated with 400 nM OA for 30 min, thereafter 8 µM phytosphingosine for 4 h. At the indicated times, cells were collected and stained with Hoechst 33342 and PI. Cells were counted using fluorescence microscopy and percentage of blue‐ and red‐stained bubbled nuclei cells (apoptotic cells) in whole cells were estimated. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

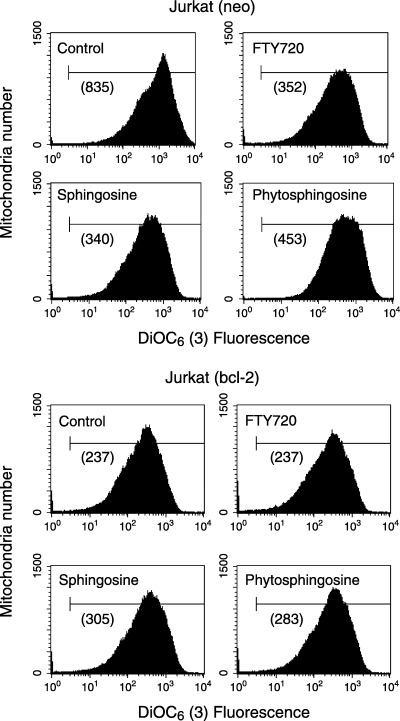

Direct reduction of the mitochondrial membrane potential of isolated mitochondria by phytosphingosine. PI 3‐kinase/Akt inhibition by phytosphingosine is necessary for amplification of apoptotic signals. It has recently been suggested that inhibition of Akt promotes pro‐apoptotic signals such as p38 activation and Bax translocation to mitochondria. 27 , 28 These indirect perturbations of mitochondria by phytosphingosine are suggested to be a phytosphingosine‐induced apoptotic mechanism. We further observed the direct effects of phytosphingosine on mitochondria using a cell‐free system. Jurkat cell mitochondria were isolated, and ΔΨm was detected. Similar to FTY720, which has already been described as a direct PT inducer, 9 , 10 phytosphingosine as well as sphingosine were found to directly decrease ΔΨm (Fig. 8). In contrast, Bcl‐2 overexpression inhibited ΔΨm reduction by phytosphingosine and sphingosine. These findings suggest that phytosphingosine perturb mitochondria by direct action as well as by an indirect mechanism.

Figure 8.

Phytosphingosine reduced ΔΨm directly in isolated Jurkat mitochondria. Mitochondria from Jurkat (neo) and (bcl‐2) cells (25 µg mitochondrial protein in 100 µL CFS buffer) were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Mitochondria were incubated with no additives, 10 µM phytosphingosine, 10 µM sphingosine, and 10 µM FTY720 (positive control) for 30 min at 37°C. Mixtures were then incubated with DiOC6(3) for 15 min, and ΔΨm was analyzed by flow cytometry. Values in parentheses indicate the median fluorescence intensity. (a), Jurkat (neo) mitochondria; (B), Jurkat (bcl‐2) mitochondria. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Discussion

In the present study, we have found that phytosphingosine‐induced apoptosis is followed by DNA fragmentation and caspase activation. Activation of caspase‐9, reduction of ΔΨm, and release of cytochrome c to the cytosol suggest that mitochondria is involved in phytosphingosine‐induced apoptosis. Phytosphingosine has been found to both directly and indirectly (by dephosphorylating Akt) perturb mitochondria. Overexpression of mitochondria‐localized anti‐apoptotic protein Bcl‐2 also inhibits phytosphingosine‐induced apoptotic stimuli, indicating that mitochondria play a significant role in phytosphingosine‐induced apoptosis.

Caspases play an important role during apoptosis, although caspase‐independent apoptosis has recently been discovered. Many caspases have now been found, and these caspase families are classified as ‘initiator’ and ‘effector’ caspases. Initiator caspases usually exist as pro‐forms in the cytosol, and these pro‐forms are cleaved by mitochondria‐ or (Fas/CD95) receptor‐mediated apoptotic signal molecules. Cleaved initiator caspases cleave effector procaspases in turn. Cleaved effector caspases perform pivotal apoptotic degradation of intracellular organelle and proteins, including nuclei, mitochondria, and caspases themselves. Thus, effector caspases activate initiator caspases, activating a caspase ‘loop’. Recently, Park et al. have revealed that phytosphingosine activates caspase‐8. (29) In the present study, we examined pivotal effector caspase, caspase‐3, and mitochondria‐ and receptor‐mediated caspase‐9 and caspase‐8, respectively. In agreement with the results of Park et al. phytosphingosine was found to activate caspase‐8, as well as caspase‐3 and caspase‐9 (Fig. 3a). However, caspase‐8 activation seemed to be at lower levels than caspase‐3 and caspase‐9 activation. This result suggests that phytosphingosine perturbs mitochondria and activates caspase‐9, which in turn activates caspase‐3. Indeed, the caspase‐3‐specific inhibitor Ac‐DEVD‐CHO was found to prevent pro‐caspase‐8 cleavage (Fig. 3b). This result suggests that phytosphingosine‐activated caspase‐8 is activated by caspase‐3.

Akt has a PH domain in its N‐terminal and a kinase domain in its C‐terminal. PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 produced by PI 3‐kinase bind to the PH domain of Akt. PDK1 allows for the phosphorylation of Akt at the Thr308 site and enables the full activation of Akt by triggering autophosphorylation on Ser473. (30) In Jurkat cells, which we used in the present study, endogenous Akt from both sites and the downstream p70S6k are phosphorylated, since Jurkat cells have a mutant form of PI 3‐phosphatase PTEN and, as a consequence, Jurkat cells contain high levels of PI (3,4,5)P3 and PI (3,4)P2. 31 , 32 , 33 Sphingosine reduces the survival factor of Akt kinase activity and induces apoptosis, (18) suggesting that the sphingosine analog phytosphingosine might also dephosphorylate Akt to induce apoptosis. In the present study, similar to sphingosine, Akt dephosphorylation occurred with phytosphingosine treatment. Moreover, Thr389 of p70S6k was dephosphorylated with phytosphingosine treatment. The downstream kinase of the PI 3‐kinase/Akt pathway, mTOR, phosphorylates p70S6k (Thr389). It is currently considered that phytosphingosine reduces Akt phosphorylation and in turn reduces mTOR activity, resulting in p70S6k (Thr389) dephosphorylation.

Moreover, in the present study, phytosphingosine did not increase the levels of phosphorylated SAPK/JNK, one of the pro‐apoptotic MAPK (Fig. 6c). Recent studies have found that other pro‐apoptotic MAPK, p38 is phosphorylated and that anti‐apoptotic MAPK, ERK1/2 is dephosphorylated with phytosphingosine treatment. (34) There is evidence that inhibition of the PI 3‐kinase/Akt pathway increases p38 signaling. Also, overexpression of constitutively active Akt down‐regulates p38 activation. (27) Furthermore, constitutively active Akt blocks pro‐apoptotic Bcl‐2 family protein Bax translocation to mitochondria. 27 , 28 The above evidence indicates that p38 and Bax are downstream from Akt, and that inactivation of Akt by phytosphingosine might activate p38 and Bax translocation to mitochondria. In addition, the ERK pathway confers protection against apoptosis by stabilizing Bcl‐2 phosphorylation. (35) These findings suggest that phytosphingosine inactivates Akt, thereby attenuating the anti‐apoptotic pathway as well as augmenting pro‐apoptotic pathways. We therefore attempted to determine how phytosphingosine reduces Akt phosphorylation. OA, a potent inhibitor of PP1 and PP2A inhibitor, has been found to partially inhibit phytosphingosine‐induced Akt dephosphorylation, allowing us to predict the involvement of PP1‐ and PP2A‐like PP (Fig. 7a). It is quite reasonable that ERK1/2 is also dephosphorylated by PP1 and/or PP2A. However, how phytosphingosine activates PP1‐ and PP2A‐like PP remains to be clarified and it still remains possible that phytosphingosine directly inhibits Akt or upstream kinases.

Phytosphingosine induces not only apoptosis but also G2/M‐phase cycle arrest of Jurkat cells. The progression from G2‐phase to M‐phase is controlled by activation of cdc2‐cyclin B complex. Hyperphosphorylation of the cdc2‐cyclin B complex progresses, and the cell cycle proceeds from G2‐phase to M‐phase. Dephosphorylation of cdc2‐cyclin B by PP cdc25 inactivates this complex and stops the cell cycle from entering M‐phase. PP cdc25 activity is controlled by upstream kinases/phosphatases, and PP2A and PP1 mediate this activity from G2‐phase to M‐phase. Phytosphingosine‐induced G2/M‐phase arrest might be involved in phytosphingosine‐induced PP up‐regulation.

Bcl‐2 blocks the PT pore‐opening and does not induce a reduction of ΔΨm or the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria. (1) In previous studies, the sphingosine analog drug FTY720 has been found to directly trigger PT, a phenomenon that is completely inhibited by Bcl‐2. (10) In the present study, similar to FTY720, phytosphingosine and sphingosine directly reduced ΔΨm. Moreover, Bcl‐2 overexpression inhibited ΔΨm reduction and further apoptotic stimuli such as caspase activation and DNA fragmentation. These results indicate that phytosphingosine might affect the PT pore or upstream molecules (e.g. Akt) to open the PT pore and to induce further apoptosis. We could not detect the effects of phytosphingosine‐induced Akt dephosphorylation on the opening of the PT pore, as Akt itself is involved in PT pore closure. (14) Phytosphingosine induces apoptosis in HL‐60RG cells, with Akt activity being attenuated in the steady state (data not shown). This finding suggests that direct perturbation of mitochondria may be the major apoptotic pathway of phytosphingosine‐induced apoptosis, and that Akt dephosphorylation may enhance this pathway. We are currently attempting to identify the binding protein of phytosphingosine and its analogs.

Phytosphingosine is abundant in yeasts and plants. (36) In animals, phytosphingosine is distributed in keratinocytes, microvillus membranes in the small intestine, and leukocytes, where there is a large amount of cell‐turnover activity. 37 , 38 , 39 Our present results shed light on the cell‐death events constituting the physiological effects of phytosphingosine. Moreover, we have found that phytosphingosine can have antitumor effects, attacking the mitochondria.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by JSPS Research Fellowships for Young Scientists.

References

- 1. Zamzami N, Marzo I, Susin SA, Brenner C, Larochette N, Marchetti P, Reed J, Kofler R, Kroemer G. The thiol crosslinking agent diamide overcomes the apoptosis‐inhibitory effect of Bcl‐2 by enforcing mitochondrial permeability transition. Oncogene 1998; 16: 1055–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Narita M, Shimizu S, Ito T, Chittenden T, Lutz RJ, Matsuda H, Tsujimoto Y. Bax interacts with the permeability transition pore to induce permeability transition and cytochrome c release in isolated mitochondria. Proceedings Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95: 14681–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu X, Kim CN, Yang J, Jemmerson R, Wang X. Induction of apoptotic program in cell‐free extracts: requirement for dATP and cytochrome c . Cell 1996; 86: 147–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Susin SA, Lorenzo HK, Zamzami N, Marzo I, Snow BE, Brothers GM, Mangion J, Jacotot E, Costantini P, Loeffler M, Larochette N, Goodlett DR, Aebersold R, Siderovski DP, Penninger JM, Kroemer G. Molecular characterization of mitochondrial apoptosis‐inducing factor. Nature 1999; 397: 441–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Verhagen AM, Ekert PG, Pakusch M, Silke J, Connolly LM, Reid GE, Moritz RL, Simpson RJ, Vaux DL. Identification of DIABLO, a mammalian protein that promotes apoptosis by binding to and antagonizing IAP proteins. Cell 2000; 102: 43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Du C, Fang M, Li Y, Li L, Wang X. Smac, a mitochondrial protein that promotes cytochrome c‐dependent caspase activation by eliminating IAP inhibition. Cell 2000; 102: 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li P, Nijhawan D, Budihardjo I, Srinivasula SM, Ahmad M, Alnemri ES, Wang X. Cytochrome c and dATP‐dependent formation of Apaf‐1/caspase‐9 complex initiates an apoptotic protease cascade. Cell 1997; 91: 479–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zou H, Henzel WJ, Liu X, Lutschg A, Wang X. Apaf‐1, a human protein homologous to C. elegans CED‐4, participates in cytochrome c‐dependent activation of caspase‐3. Cell 1997; 90: 405–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fulda S, Scaffidi C, Susin SA, Krammer PH, Kroemer G, Peter ME, Debatin KM. Activation of mitochondria and release of mitochondrial apoptogenic factors by betulinic acid. J Biol Chem 1998; 273: 33942–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nagahara Y, Ikekita M, Shinomiya T. Immunosuppressant FTY720 induces apoptosis by direct induction of permeability transition and release of cytochrome c from mitochondria. J Immunol 2000; 165: 3250–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Luo X, Budihardjo I, Zou H, Slaughter C, Wang X. Bid, a Bcl2 interacting protein, mediates cytochrome c release from mitochondria in response to activation of cell surface death receptors. Cell 1998; 94: 481–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Toker A. Protein kinases as mediators of phosphoinositide 3‐kinase signaling. Mol Pharmacol 2000; 57: 652–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zha J, Harada H, Osipov K, Jockel J, Waksman G, Korsmeyer SJ. BH3 domain of BAD is required for heterodimerization with BCL‐xL and pro‐apoptotic activity. J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 24101–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gottlob K, Majewski N, Kennedy S, Kandel E, Robey RB, Hay N. Inhibition of early apoptotic events by Akt/PKB is dependent on the first committed step of glycolysis and mitochondrial hexokinase. Genes Dev 2001; 15: 1406–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pastorino JG, Shulga N, Hoek JB. Mitochondrial binding of hexokinase II inhibits Bax‐induced cytochrome c release and apoptosis. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 7610–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cardone MH, Roy N, Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS, Franke TF, Stanbridge E, Frisch S, Reed JC. Regulation of cell death protease caspase‐9 by phosphorylation. Science 1998; 282: 1318–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Ceramide: an intracellular signal for apoptosis. Trends Biochem Sci 1995; 20: 73–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chang HC, Tsai LH, Chuang LY, Hung WC. Role of AKT kinase in sphingosine‐induced apoptosis in human hepatoma cells. J Cell Physiol 2001; 188: 188–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tamiya‐Koizumi K, Murate T, Suzuki M, Salvesen GS, Franke TF, Stanbridge E, Frisch S, Reed JC. Inhibition of DNA primase by sphingosine and its analogues parallels with their growth suppression of cultured human leukemic cells. Biochem Mol Biol Int 1997; 41: 1179–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ruvolo PP. Intracellular signal transduction pathways activated by ceramide and its metabolites. Pharmacol Res 2003; 47: 383–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hannun YA, Loomis CR, Merrill AH Jr, Bell RM. Sphingosine inhibition of protein kinase C activity and of phorbol dibutyrate binding in vitro and in human platelets. J Biol Chem 1986; 261: 12604–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Merrill AH Jr, Sereni AM, Stevens VL, Hannun YA, Bell RM, Kinkade JM Jr. Inhibition of phorbol ester‐dependent differentiation of human promyelocytic leukemic (HL‐60) cells by sphinganine and other long‐chain bases. J Biol Chem 1986; 261: 12610–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Raeder EM, Mansfield PJ, Hinkovska‐Galcheva V, Kjeldsen L, Shayman JA, Boxer LA. Sphingosine blocks human polymorphonuclear leukocyte phagocytosis through inhibition of mitogen‐activated protein kinase activation. Blood 1999; 93: 686–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Simbulan CM, Tamiya‐Koizumi K, Suzuki M, Shoji M, Taki T, Yoshida S. Sphingosine inhibits the synthesis of RNA primers by primase in vitro . Biochemistry 1994; 33: 9007–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hung WC, Chang HC, Chuang LY. Activation of caspase‐3‐like proteases in apoptosis induced by sphingosine and other long‐chain bases in Hep3B hepatoma cells. Biochem J 1999; 338 (1): 161–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Matsuoka Y, Nagahara Y, Ikekita M, Shinomiya T. A novel immunosuppressive agent FTY720 induced Akt dephosphorylation in leukemia cells. Br J Pharmacol 2003; 138: 1303–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gratton JP, Morales‐Ruiz M, Kureishi Y, Fulton D, Walsh K, Sessa WC. Akt down‐regulation of p38 signaling provides a novel mechanism of vascular endothelial growth factor‐mediated cytoprotection in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 30359–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tsuruta F, Masuyama N, Gotoh Y. The phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase (PI3K) ‐Akt pathway suppresses Bax translocation to mitochondria. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 14040–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Park MT, Kang JA, Choi JA, Kang CM, Kim TH, Bae S, Kang S, Kim S, Choi WI, Cho CK, Chung HY, Lee YS, Lee SJ. Phytosphingosine induces apoptotic cell death via caspase 8 activation and Bax translocation in human cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res 2003; 9: 878–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Toker A, Newton AC. Akt/protein kinase B is regulated by autophosphorylation at the hypothetical PDK‐2 site. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 8271–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wen S, Stolarov J, Myers MP, Su JD, Wigler MH, Tonks NK, Durden DL. PTEN controls tumor‐induced angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001; 98: 4622–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bruni P, Boccia A, Baldassarre G, Trapasso F, Santoro M, Chiappetta G, Fusco A, Viglietto G. PTEN expression is reduced in a subset of sporadic thyroid carcinomas: evidence that PTEN‐growth suppressing activity in thyroid cancer cells mediated by p27kip1 . Oncogene 2000; 19: 3146–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shan X, Czar MJ, Bunnel SC, Liu P, Liu Y, Schwartzberg PL, Wange RL. Deficiency of PTEN in Jurkat T cells causes constitutive localization of Itk to the plasma membrane and hyperresponsiveness to CD3 stimulation. Mol Cell Biol 2000; 20: 6945–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Park MT, Choi JA, Kim MJ, Um HD, Bae S, Kang CM, Cho CK, Kang S, Chung HY, Lee YS, Lee SJ. Suppression of extracellular signal‐related kinase and activation of p38 MAPK are two critical events leading to caspase‐8‐ and mitochondria‐mediated cell death in phytosphingosine‐treated human cancer cells. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 50624–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tamura Y, Simizu S, Osada H. The phosphorylation status and anti‐apoptotic activity of Bcl‐2 are regulated by ERK and protein phosphatase 2A on the mitochondria. FEBS Lett 2004; 569: 249–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dickson RC. Sphingolipid functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: comparison to mammals. Annu Rev Biochem 1998; 67: 27–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schurer NY, Plewig G, Elias PM. Stratum corneum lipid function. Dermatologica 1991; 183: 77–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Flamand N, Justine P, Bernaud F, Rougier A, Gaetani Q. In vivo distribution of free long‐chain sphingoid bases in the human stratum corneum by high‐performance liquid chromatographic analysis of strippings. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl 1994; 656: 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bodennec J, Zwingelstein G, Koul O, Brichon G, Portoukalian J. Phytosphingosine biosynthesis differs from sphingosine in fish leukocytes and involves a transfer of methyl groups from [3H‐methyl]methionine precursor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1998; 250: 88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]