Abstract

A member of the family of p53‐related genes, p63 plays a role in regulating epithelial proliferation and differentiation programs, but the pathological and clinical meaning of p63 in B‐cell lymphoma has not been elucidated. We investigated the expression pattern of p63 in B‐cell malignancies, and evaluated the correlation between the expression of p63 and other germinal center markers. Ninety‐eight B‐cell lymphomas (28 FCL, 5 MCL, and 65 DLBCL) were analyzed by immunohistochemical examination for p63, bcl‐6, CD10 and MUM‐1 proteins, and for rearrangement of bcl‐2/IgH. Expression of p63 was observed in the nuclei of tumor cells obtained from 15 of 28 (54%) FCL, 22 of 65 (34%) DLBCL, but none of 5 MCL. In DLBCL, the expression of p63 and bcl‐6 showed a significant correlation (P < 0.02), but no correlation was observed between p63 and expression of CD10, MUM‐1, or bcl‐2/IgH rearrangement. RT‐PCR revealed that TAp63α‐type transcripts, a possible negative regulator of transcriptional activation of p21 promoter, were major transcripts in B‐cell lymphoma tissues. As for prognostic significance, only patients in the p63 positive group of FCL died, and in the non‐germinal center group, the p63 positive cases appeared to have inferior overall survival than other groups in DLBCL. Our preliminary results suggested that p63 expression is a disadvantageous factor for prognosis in this subgroup of B‐cell lymphomas. (Cancer Sci 2006; 97: 1050–1055)

Abbreviations:

- CD

cytoplasmic domain

- DLBCL

diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma

- FCL

follicular cell lymphoma

- FLIPI

Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index

- GCB

germinal center‐like B‐cell

- IgH

immunoglobulin heavy chain

- IPI

Internal Prognostic Factors Index

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- MBR

major breakpoint region

- MCL

mantle cell lymphoma

- MCR

minor cluster region

- OS

overall survival

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RT‐PCR

reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

- WHO

World Health Organization.

A family member of p53‐related genes, p63 has been reported to be a regulator of epithelial proliferation and differentiation programs.( 1 , 2 , 3 ) A generation of p63‐null mice has confirmed the crucial role of p63 in maintaining surface epithelium. These mice were born with a lack of stratification of the skin, and this lack of p63 expression also leads to defects in epidermal differentiation, mammary glands, lacrimal glands and prostate. p63 protein is mainly expressed in the nuclei of the basal layer cell in the epidermis, as well as in hair follicles, sweat glands, and the basal epithelia of the esophagus, breast and prostate. In addition, heterozygous germ line point mutations of the p63 gene have been found in several human autosomal dominant developmental disorders, including ectodactyly ectodermal dysplasia clefting syndrome, limb–mammary syndrome and acro‐dermato‐ungual‐lacrimal‐tooth syndrome.( 4 ) Evidence from these organs showed that p63 is a key regulator of their development.

In contrast to the well‐known p53 function as a tumor suppressor gene, studies of primary human tumors and cell lines have indicated a possible role of p63 in the growth and development of epithelial tumors.( 1 , 2 , 5 ) Overexpressions of p63, for example, have been found squamous cell carcinomas in the esophagus, head and neck, and lung. The functional role of p63 in lymphoid tissue development has not yet been elucidated, but p63 protein in the normal lymph node is occasionally expressed in germinal center cells.( 6 , 7 , 8 ) Furthermore, Di Como et al. observed the expression of p63 in part of a subset of non‐Hodgkin's B‐cell lymphoma that included FCL and DLBCL.( 6 ) Pruneri et al.( 9 ) showed that p63 protein and mRNA expression were higher in follicular lymphoma grade 3 than in follicular lymphoma grade 1 or 2. These results indicate that p63 protein expression might be associated with lymphomagenesis, but the pathological, cytogenetical and clinical significance of p63 expression in lymphoid malignancies remains unclear.

DLBCL is a heterogeneous group, with morphological subtypes that include centroblastic, immunoblastic, T‐cell/histiocyte rich and anaplastic, by WHO classification. The cell origin of DLBCL is thought to be peripheral B‐cells of either germinal center or postgerminal center cells.( 10 ) To investigate the relationship between p63 expression and the stage of B‐cell differentiation, we carried out immunohistochemistry for p63 expression as well as the expressions of the antigens that are differentially expressed at the germinal center and postgerminal center stage of B‐cell differentiation (CD10, bcl‐6 and MUM‐1). CD10, a membrane‐associated neutral endopeptidase, has a restricted expression in the germinal center cells of reactive lymphoid tissues,( 11 ) and is widely accepted as a reliable marker for FCL. Bcl‐6, a zinc‐finger protein that acts as a transcriptional repressor and is necessary for germinal center formation,( 12 , 13 ) is highly expressed in germinal center B‐cell and tumors derived from the germinal center, such as FCL.( 14 , 15 )

MUM‐1/IRF‐4 is a lymphoid‐specific member of the interferon regulatory factor of transcription factors.( 16 ) The protein is normally expressed in plasma cells and a minor subset of germinal center cells. In previous reports, 50–77% of DLBCL expressed MUM‐1.( 16 , 17 , 18 ) Based on these results, immunohistochemical examination using CD10, bcl‐6 and MUM‐1 as markers to classify the cases of DLBCL into germinal center B‐cell or non‐germinal center B‐cell lymphoma( 18 , 19 ) has been reported. We also investigated the association between p63 expression and the presence of bcl‐2/IgH rearrangement, using PCR. The bcl‐2/IgH rearrangement is caused by a t(14; 18) translocation juxtaposes the bcl‐2 oncogene on chromosome 18 to the IgH gene on chromosome 14. This alteration is found in 67–90% of patients with FCL,( 20 , 21 ) and in approximately one‐third of DLBCL patients.( 22 ) DLBCL with the gene alteration is thought to be of germinal center origin.( 23 )

We studied the expression of p63 in B cell lymphoma in Japanese patients by immunohistochemistry and RT‐PCR, and report here the relationship between the expression of p63 and other germinal center markers and clinical characteristics in B‐cell lymphoma.

Materials and Methods

Patients. Twenty‐eight patients with FCL, five patients with MCL and 65 patients with DLBCL diagnosed between 1993 and 2004 were included in this study. Tissue samples were obtained from surgical specimens, and were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. All specimens were stained with hematoxylin–eosin for morphological diagnosis, and imprint smears of the surgically resected specimens were carried out using Giemsa staining. Patients were reviewed morphologically according to the criteria of WHO classification( 10 ) by two researchers (N.F., T.S.), and were evaluated for CD20, CD79a, CD5, CD10, CD3, UCHL‐1, cyclin D1, CD23 and CD30 by immunohistochemistry or flowcytometry. Chromosomal examination and Southern blot hybridization for IgH/JH and TCRcβ rearrangement were conducted. Patients with immunodeficiency‐associated tumors, primary mediastinal, intravascular, Burkitt's‐like lymphoma, and lymphomatoid granulomatosis were excluded from the study. Clinical data were obtained from the lymphoma database of the division of hematology, Saga University Hospital. The clinical stage was scored using the Ann Arbor staging classification. Each patient had undergone chest X‐ray, neck to pelvic computed tomography, Gallium scintigraphy, upper and lower gastrointestinal tract studies and bone marrow examination. In MCL and DLBCL, IPI scores were calculated, with one point assigned for each of the following criteria: age over 60 years; stage more than III; an elevated serum LDH; extranodal site, more than 1; and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of more than 2. For FCL, we also used FLIPI.( 24 ) The scores were calculated at the point of diagnosis assigned for each of the following criteria: age over 60 years; stage more than III; elevated serum LDH; nodal site more than 4; and hemoglobin less than 12 g/dL. The clinical features are summarized in Table 1. Most patients had undergone induction chemotherapy, such as CHOP or CHOP‐like regimens with/without rituximab. Some patients received other chemotherapy regimens, surgery or steroids only, because of individual reasons. OS was calculated from the date of diagnosis. All procedures were carried out with informed consent and the Saga University Institutional Review Board committee approved this genetics study.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with FCL, MCL and DLBCL assessed in this study

| FCL | MCL | DLBCL | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 28 | 5 | 65 |

| Age range in years (median) | 27–80 (56) | 53–77 (63) | 21–88 (70) |

| Over 60 years of age (%) | 12 (43) | 4 (80) | 53 (81) |

| Gender (M:F) | 12:16 | 3:2 | 41:24 |

| PS | |||

| 0–1 | 23 | 5 | 47 |

| 2–4 | 5 | 0 | 18 |

| Stage | |||

| I | 1 | 0 | 11 |

| II | 4 | 1 | 21 |

| III | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| V | 21 | 3 | 25 |

| Extra > 1 | 8 | 2 | 14 |

| LDH > normal | 4 | 2 | 34 |

| Hb < 12 g/dL | 6 | ND | ND |

| Nodal site > 4 | 10 | ND | ND |

| FLIPI | |||

| Low | 10 | NA | NA |

| Intermediate | 12 | NA | NA |

| High | 6 | NA | NA |

| IPI | |||

| Low | 13 | 0 | 18 |

| Low‐intermediate | 10 | 3 | 24 |

| High‐intermediate | 3 | 1 | 11 |

| High | 2 | 1 | 12 |

Hb, hemoglobine; NA, not applicable; PS, performance status.

Detection of splicing variant of p63 mRNA. Total RNA was isolated from 10 lymph node specimens, one subcutaneous tumor and two tonsil specimens of patients by ISOGEN reagent (Nippon Gene, Japan). One µg total RNA was applied to RT with MuLV reverse transcriptase (Roche Molecular Systems, NJ) at 37°C for 60 min, and the obtained cDNAs were applied to PCR. Specific primers and PCR conditions for each splicing variant were as follows:( 6 ) TAp63 sense, 5′‐GTCCCAGAGCACACAGACAA‐3′ and antisense, 5′‐GAGGAGCCGTTCTGAATCTG‐3′, 40 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 57°C for 40 s, 72°C for 30 s; ΔNp63 sense, 5′‐CTGGAAAACAATGCCCAGAC‐3′ and antisense, 5′‐GGGTGATGGAGAGAGAGCAT‐3′, 40 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 57°C for 40 s, 72°C for 30 s; p63α‐tail sense, 5′‐GAGGTTGGGCTGTTCATCAT‐3′ and antisense, 5′‐AGGAGATGAGAAGGGGAGGA‐3′, two cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 57°C for 40 s, 72°C for 30 s, followed by 38 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 40 s, 72°C for 30 s; p63β‐tail sense, 5′‐CCTACAACCATTCCTGATGGC‐3′ and antisense, 5′‐CAGACTTGCCAGATCCTGA‐3′, two cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 57°C for 40 s, 72°C for 30 s, followed by 38 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 40 s, 72°C for 30 s; p63γ‐tail sense, 5′‐CGTCAGAACACACATGGTATCC‐3′ and antisense, 5′‐AAGCTCATTCCTGAAGCAGGC‐3′, two cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 57°C for 40 s, 72°C for 30 s, followed by 38 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 40 s, 72°C for 30 s. Specificity of the amplified PCR product was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis, followed by staining with ethidiumbromide. β‐actin mRNA was used as a housekeeping gene to ensure the quality of the obtained cDNAs.

Immunohistochemistry. Immunohistochemical analysis was carried out by the avidin–biotin peroxidase complex method. In brief, deparaffinized 4 µm‐thin tissue sections were placed in a microwave oven in a 0.01 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 min at 95–99°C, or pressure cooked for 10 min in EDTA buffer (CD10; 1 mM, pH 8.0 MUM‐1; pH 9.0) for antigen retrieval. After tissue sections were blocked with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in phosphate‐buffered saline for 30 min at room temperature, each section was incubated overnight at 4°C with antibodies against p63 (4A4, dilution 1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA), bcl‐6 (D‐8, dilution 1:400; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), CD10 (56C6, dilution 1:50; Novocastra, Newcastle, UK), and MUM‐1 (ab12501, dilution 1:50; Abcam, Cambridge, UK). After washing, samples were incubated with Envision + system labeled polymer‐horseradish peroxidase anti‐mouse (DakoCytomation) for 30 min. Diaminobenzidine with H2O2 was used as the chromogen, hematoxylin as the nuclear counter stain. The number of p63 stained cells was determined and results were scored by estimating the percentage of tumor cells showing characteristic nuclear staining (0–20%, negative; 21% or more, positive). Nuclear staining of epithelial basal cells was used as a positive internal control for p63, if present. We decided that more than 20% of tumor cells showing nuclear staining was considered positive for p63 immunostaining. Apparent staining in more than 20% of tumor cells was taken as positive for bcl‐6 (nuclear staining) and CD10 (cytoplasmic staining) in a previous report.( 11 ) MUM‐1 immunostaining was considered positive if nuclear staining was observed in more than 30% of tumor cells in a previous report.( 18 )

Bcl‐2/IgH rearrangement by PCR. PCR was carried out for detection of the presence of t(14; 18) (q32;q21) (bcl‐2/IgH) in 14 FCL, 5 MCL and 33 DLBCL. Genomic DNA was extracted from formalin‐fixed, paraffin‐embedded sections using the QIAMP DNA mini‐kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The sequences of primer sets used for detection of the MBR and the MCR were as follows:( 24 ) MBR primer, 5′‐GAG TTG CTT TAC GTG GCC TG; MCR primer, 5′‐GAC TTC TTT ACG TGC TGG TAC C; JH primer, 5′‐ACC TGA GGA GAC GGT GAC C. PCR was carried out with an automated thermocycler using a modification of published conditions. Initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min was followed by 43 cycles of a three‐step amplification process of a denaturation step at 95°C for 30 s, an annealing step at 60°C for 15 s and an extension step at 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final extension step of 72°C for 10 min. DNA from an FCL case with bone marrow infiltration was used as a positive control. The PCR products were analyzed using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under ultraviolet light.

Statistical analysis. We used Fisher's exact test to identify correlations for categorical data. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant in all analyses. The OS analysis was carried out according to the method described by Kaplan and Meier,( 26 ) and the curves were compared by the log–rank test. All tests were carried out using StatView version 5.0 software (SAS Institute).

Results

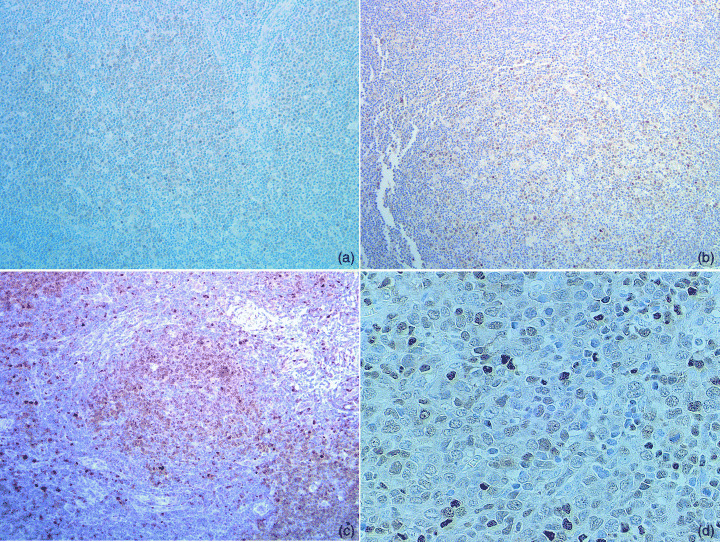

p63 immunostaining in non‐Hodgkin's B‐cell lymphoma. A specimen from reactive lymphadenitis, which expressed p63 protein mainly in nuclei of germinal center cells and not in mantle cells, was used as a positive control. FCL were morphologically further subclassified as grade 1 (14/28, 50%), 2 (5/28, 18%) or 3 (9/28, 32%; 7 of 3a and 2 of 3b), based on the WHO classification. Fifteen of 28 (54%) cases showed positive staining with an anti‐p63 antibody, 4A4, in the nuclei of tumor cells (Table 2). The intensity and the number of positive cells were more prominent in centroblastoid cells compared with centrocytes in neoplastic follicles (Fig. 1a–c). In addition, positive p63 immunostaining was higher in grade 3 FCL (7/9, 78%; 5 of 7 in 3a and 2 of 2 in 3b) than in grade 1 or 2 (6/14, 43%; 2/5, 40%, respectively). None of the five MCL cases showed positive staining for p63. In DLBCL, 22 of 65 (34%) cases showed positive p63 immunostaining (Table 2) (Fig. 1d). Although the intensity and percentage of positive cells with p63 immunostaining varied with the cases, no correlation was observed in histological subtypes, such as centroblastic, immunoblastic, histiocyte‐rich, or anaplastic large cell type, by WHO criteria.

Table 2.

Positive staining of immunohistochemistry for germinal center markers and bcl‐2/IgH rearrangement

| FCL n (%) | DLBCLn (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of cases | 28 | 65 |

| p63 | 15 (54) | 22 (34) |

| bcl‐6 | 19 (68) | 43 (66) |

| CD10 | 21 (75) | 17 (26) |

| MUM‐1 | 0 (0) | 39 (60) |

| bcl2/IgH | 10/14 (71) | 13/33 (39) |

Figure 1.

Representative photomicrographs of immunostaining with an anti‐p63 antibody, 4A4. Follicular lymphoma grade 1 (a), grade 2 (b) and grade 3 (c) (original magnifications: × 100), and diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma (d) (original magnification: × 400).

Association of p63 expression with bcl‐6, but not with p53 immunostaining. The discrimination of germinal center type from non‐germinal center cell origin using several germinal center markers is thought to be useful for prediction of survival in DLBCL. Therefore we examined the association of p63 immunostaining with germinal center marker expressions, or bcl‐2/IgH rearrangement in FCL and DLBCL. Bcl‐6 immunostaining was positive for 19 of 28 cases (68%) in FCL, and there was a statistically significant correlation with p63 expression (P < 0.05). CD10 expression was observed in 21 of 28 (75%) cases and no positive cases for MUM‐1 immunostaining. The rearrangement of bcl‐2/IgH was detected in seven (50%) and six (49%) of 14 cases by PCR analysis using MBR primer and MCR primer sets, respectively. Ten of 14 cases (71%) showed bcl‐2/IgH rearrangement in MBR or MCR, and rearrangement in both MBR and MCR was detected in three cases. p53 immunostaining was not associated with p63 expression (data not shown).

In DLBCL, Bcl‐6 protein was expressed in 43 of 65 (66%) cases. Nineteen of 22 (86%) cases showed positive immunostaining both for p63 and bcl‐6, whereas 24 of 43 (56%) cases expressed bcl‐6 alone (P < 0.02) (Table 3). Among other markers, no correlation between p63 and CD10 or MUM‐1 was observed, although an inverse correlation between CD10 and MUM‐1 (P < 0.0001) and a tendency toward inverse correlation between bcl‐6 and MUM‐1 (P = 0.06) were observed. We classified cases of DLBCL into GCB and non‐GCB using the expression patterns of bcl‐6, CD10 and MUM‐1, as reported previously.( 18 ) Among GCB‐like DLBC cases (n = 24), 9 of 24 (38%) were positive for p63, and 13 of 41 (32%) were positive in the non‐GCB group (Table 3). p63 expression was not associated with p53 immunostaining in DLBCL.

Table 3.

Relationship between p63 and germinal center markers in diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma

| p63 | Totaln | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +n (%) | –n (%) | ||||

| bcl‐6 | + | 19 (29) | 24 (37) | 43 | <0.02 |

| – | 3 (5) | 19 (29) | 22 | <0.02 | |

| CD10 | + | 5 (8) | 12 (18) | 17 | NS |

| – | 17 (26) | 31 (48) | 48 | NS | |

| MUM‐1 | + | 14 (22) | 25 (38) | 39 | NS |

| – | 8 (12) | 18 (28) | 26 | NS | |

| GCB | 9 (14) | 15 (23) | 24 | NS | |

| Non‐GCB | 13 (20) | 28 (43) | 41 | NS | |

| Total | 22 | 43 | 65 | ||

+, positive; –, negative; NS, not siginificant.

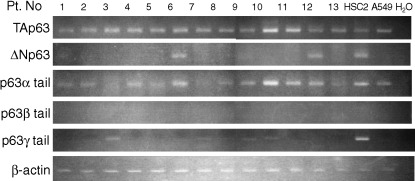

Expression of splicing variants of p63 mRNA in B‐cell lymphoma. RT‐PCR was carried out for detection of p63 mRNA expression in B‐cell lymphomas. TAp63 type (α/β/γ) type transcripts contain a transactivation domain with homology to the transactivation domain of p53. ΔN type p63 (α/β/γ) lacks a transactivation domain, but retains a DNA‐binding domain that can bind to a consensus sequence of p53. It is thought to act as a dominant negative repressor to p53 or p63 induced gene expression. Thirteen samples were analyzed by RT‐PCR, and results are summarized in Figure 2. To confirm the specificity of the PCR products, those obtained from positive cases were analyzed by direct sequence. TAp63 type transcripts were observed in all 13 cases, but only two cases expressed ΔN type transcripts. The samples of both cases were obtained from tonsil, and contained squamous epithelia confirmed by hematoxylin–eosin staining. Splicing variants of C‐termini, such as α, β or γ type transcripts were also analyzed. Alpha type transcripts were detected in all 13 cases, and all expressed TAp63 type transcripts. In contrast, no apparent expression of β type transcripts was observed, and approximately half (6/13) of the cases expressed γ type transcripts. These results indicated that TAp63α form transcripts were major products in B‐cell lymphoma, and the ΔN type transcripts observed in two cases were likely due to contamination from tonsilar squamous epithelia. As p21, a cyclin‐dependent kinase, is thought to be a target gene of p63, we analyzed p21 mRNA expression in 13 samples of lymphoma patients and lymphocytes obtained from peripheral blood of normal volunteers by RT‐PCR. However, no detectable level of p21 mRNA was observed either in normal peripheral lymphocytes or in lymphoma samples (data not shown).

Figure 2.

RT‐PCR for the detection of isoforms of p63. RT‐PCR analyses were carried out using isoform‐specific primers of p63 gene. Lanes 1, 4, 6, 7, 11, 13, follicular lymphoma; other lanes, diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. β‐actin was used as an endogenous standard. A549, a lung cancer‐derived cell line; HSC2, an oral squamous cell carcinoma‐derived cell line.

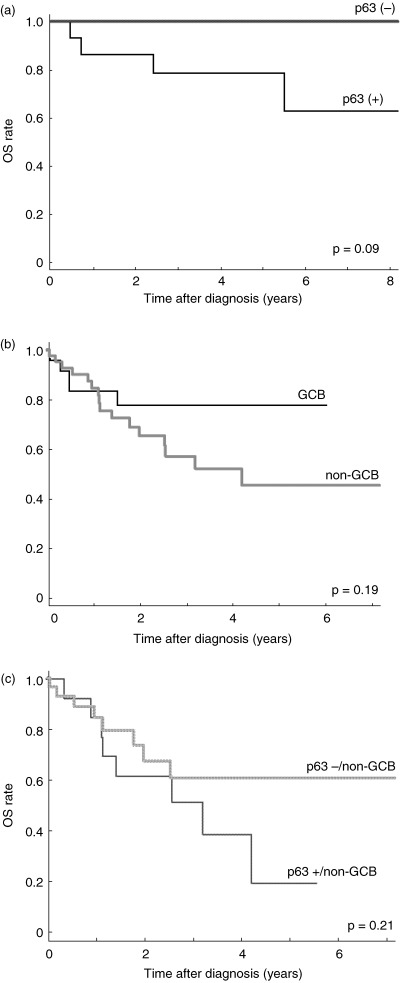

p63 expression and impact survival of B‐cell lymphomas. Next, we analyzed the clinical characteristics of p63 expression in B‐cell lymphomas. No significant correlation between p63 expression and clinical parameters was observed in any patients. For FCL, a significant correlation was noted by IPI subclassification, when the cases were divided into two groups (low/low–intermediate and high–intermediate/high) (P = 0.005). Deceased patients were found only in the p63 positive group of FCL (P = 0.09) (Fig. 3a). For DLBCL, there was a significant difference in OS by IPI (P = 0.002). In terms of subclassification as GCB or non‐GCB type DLBCL, there was a tendency toward improved survival in GCB rather than in non‐GCB type (Fig. 3b). Although the p63 positive group in non‐GCB type showed a weak association toward inferior OS compared with the p63 negative group (P = 0.21) (Fig. 3c), a tendency toward poor prognosis in the p63 positive group was observed when OS was calculated in terms of survival period observation from start to 2 years or later (P = 0.088 for 2 years or later, and P = 0.109 for 1 year or later, showing time dependability). Although the results are not statistically significant because of the small number of evaluations, the p63 positive group in non‐GCB type included 6 of 13 (46.2%) high or high–intermediate risk cases by IPI score (mean = 2.77), 6 of 24 (25.0%) in the p63 negative group in non‐GCB type (mean IPI = 2.29). Among various clinical parameters in non‐GCB type, serum LDH levels tended to be higher in the p63 positive group (mean LDH = 379.2) than in the p63 negative group (mean LDH = 272.2). No such difference was found for GCB type.

Figure 3.

OS curves in the subtypes of B‐cell lymphoma. (a) Comparison of p63 positive (+) and negative (–) groups in follicular lymphoma. (b) Overall survival curves subclassified as germinal center B‐cell or non‐germinal center B‐cell types assessed by immunohistochemical analyses in diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. (c) Comparison of p63 positive (+) and negative (–) groups in non‐germinal center B‐cell types of diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma.

Discussion

We report here that p63 expression was observed in 54% of FCL, especially in grade 3 subtype (78%), and 34% of DLBCL. The results were quite consistent with previous reports,( 6 , 9 ) although the p63 positive rate in grade 1 and 2 FCL was slightly higher in our study. Normal germinal center cells moderately expressed p63 protein, and the p63 protein level seems to be related to the number of centroblasts in FCL. In addition, no MCL cases expressed a detectable level of p63 protein by immunohistochemistry. Therefore, we hypothesize that p63 is a possible germinal center marker for DLBCL. We found a close correlation between p63 expression and bcl‐6 immunostaining, a reliable germinal center marker (P < 0.02), but the expression of p63 was not associated with other germinal or non‐germinal center markers, such as CD10, bcl‐2/IgH rearrangement, or MUM‐1 expression. By classifying DLBCL into GCB or non‐GCB type using these markers, positive rates of imunostaining with p63 were very similar to those in GCB (38%) or non‐GCB type (32%). Thus, the association of p63 and bcl‐6 expressions was an independent phenomenon of the expression of other germinal center markers. As p63 and bcl‐6 are located on chromosome 3q28 and 3q27, respectively, one of the explanations for the coexpression of the genes is gene amplification of the loci. Pruneri et al. recently reported that chromosome 3 trisomy or polysomy was detected in 24% of FCL cases using fluorescence in situ hybridization, and one of those cases showed colocalization of p63 and bcl‐6 genes in tumor cells.( 9 ) However, the prevalence of p63 immunoreactivity in FCL was not obviously associated with gene abnormalities, suggesting that coexpression of p63 with bcl‐6 in non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma are mediated through complex mechanisms. In addition, confirming previous reports, p63 expression showed no association with p53 expression.( 6 )

Looking at the role of p63 expression in lymphomagenesis, several reports have presented the results on the expression profile of isoforms of p63 in lymphoma. Di Como et al.( 6 ) reported that detectable levels of α, β and γ TAp63 isoforms were observed in three FCL cases and three DLBCL cases, although two of these also showed ΔNp63 expression. However, Pruneri et al. reported that none of 12 FCL showed ΔNp63 mRNA expression.( 9 ) Our study also found TAp63 in the major transcripts, and the expressions of ΔNp63 isoforms were due to contamination of tonsilar squamous epithelia. In addition, we found that TAp63α transcripts were observed in all B‐cell lymphoma examined, whereas only half of the cases expressed TAp63γ type transcripts. Recent studies have shown that TAp63γ is the most transcriptionally active isoform mediated through binding with transcriptional coactivator p300, regulating gene expression such as p21.( 27 ) TAp63α contains a sterile α motif implicated in protein–protein interaction and thought to be a negative regulator of TAp63γ form. These results suggest that dysregulation of TAp63γ expression or overexpression of TAp63α isoform might be implicated in tumor occurrence or progression of B‐cell lymphoma. Although we found no detectable level of p21 mRNA expression in any lymphoma tissue examined, further in vivo study will be required to confirm the implication of TAp63α isoform for tumor occurrence or progression of B‐cell lymphoma.

Our preliminary study showed that p63 expression, probably TAp63α expression, associated with poor prognosis of non‐GCB type DLBCL, although the results were not statistically significant. Some studies have reported a relationship between p63 immunoreactivity and clinical characteristics or prognosis in solid tumors. Zigeuner et al. showed that decreased p63 immunoreactivity was significantly associated with advanced tumor stages and poor prognosis in transitional cell carcinoma.( 28 ) Massion et al. also showed that the p63 overexpression group had prolonged survival in non‐small‐cell lung cancer patients.( 29 ) In contrast to solid tumors, Hedvat et al. reported that p63 expression was correlated with a high proliferation index assessed by Ki‐67 immunostaining in DLBCL.(32) They did not find any clear association between p63 expression and overall survival, but it is possible that p63 overexpression could correlate with aggressiveness of B‐cell lymphoma. Subclassification by FLIPI in the FCL group did not show any clear difference for OS, and the impact of the markers on OS by discrimination of GCB and non‐GCB was not clear in our small‐scale study. However, a tendency toward poor prognosis was observed in the p63 positive group of FCL and that of the non‐GCB group. A large‐scale study is required to clarify the meaning of p63 overexpression in B‐cell lymphoma, more specifically in FCL and the non‐GCB subgroup in DLBCL.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the following Grants‐in Aid for Cancer Research: Special Cancer Research, from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan; and from the Uehara Memorial Foundation. We thank Dr Kazue Imai for her appropriate advice regarding the statistical analysis. We thank Junko I and Fumihiro Muto for their excellent technical assistance.

References

- 1. Mills AA, Zheng B, Wang XJ, Vogel H, Roop DR, Bradley A. p63 is a p53 homologue required for limb and epidermalmorphogenesis. Nature 1999; 398: 708–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yang A, Schweitzer R, Sun D et al. p63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial, and epithelial development. Nature 1999; 398: 714–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marin MC, Kaelin WG Jr. p63 and p73: old members of a new family. Biochim Biophys Acta 2000; 1470: 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brunner HG, Hamel BC, Van Bokhoven H. The p63 gene in EEC and other syndromes. J Med Genet 2002; 39: 377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Levrero M, De Laurenzi V, Costanzo A, Gong J, Wang JY, Melino G. The p53/p63/p73 family of transcription factors: overlapping and distinct functions. J Cell Sci 2000; 113: 1661–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Di Como CJ, Urist MJ. Babayan et al. p63 expression profiles human normal tumor tissues. Clin Cancer Res 2002; 8: 494–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hall PA, Campbell SJ, O’Neill M et al. Expression of the p53 homologue p63alpha and deltaNp63alpha in normal and neoplastic cells. Carcinogenesis 2000; 21: 153–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nylander K, Vojtesek B, Nenutil R et al. Differential expression of p63 isoforms in normal tissues and neoplastic cells. J Pathol 2002; 198: 417–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pruneri G, Fabris S, Dell’orto P et al. The transactivating isoforms of p63 are overexpressed in high‐grade follicular lymphomas independent of the occurrence of p63 gene amplification. J Pathol 2005 July; 206 (3): 337–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gatter KC, Warnke RA. Diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. In: Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW, eds. WHO Classification of Tumors. Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon: IARC Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dogan A, Bagdi E, Munson P, Isaacson PG. CD10 and BCL‐6 expression in paraffin sections of normal lymphoid tissue and B‐cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2000; 24: 846–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chang CC, Ye BH, Chaganti RS, Dalla‐Favera R. BCL‐6, a POZ/zinc‐finger protein, is a sequence‐specific transcriptional repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996; 93: 6947–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pasqualucci L, Bereschenko O, Niu H et al. Molecular pathogenesis of non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma: the role of Bcl‐6. Leuk Lymphoma 2003; 44 (Suppl. 3): 5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ree HJ, Yang WI, Kim CW et al. Coexpression of Bcl‐6 and CD10 in diffuse large B‐cell lymphomas: significance of Bcl‐6 expression patterns in identifying germinal center B‐cell lymphoma. Hum Pathol 2001; 32: 954–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ree HJ, Ohshima K, Aozasa K et al. Detection of germinal center B‐cell lymphoma in archival specimens: critical evaluation of Bcl‐6 protein expression in diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma of the tonsil. Hum Pathol 2003; 34: 610–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feline B, Biscotti M, Puckering A et al. A monoclonal antibody (MUM1p) detects expression of the MUM1/IRF4 protein in a subset of germinal center B cells, plasma cells, and activated T cells. Blood 2000; 95: 2084–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Natkunam Y, Warnke RA, Montgomery K, Falini B, Van De Rijn M. Analysis of MUM1/IRF4 protein expression using tissue microarrays and immunohistochemistry. Mod Pathol 2001; 14: 686–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC et al. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood 2004; 103: 275–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Colomo L, Lopez‐Guillermo A, Perales M et al. Clinical impact of the differentiation profile assessed by immunophenotyping in patients with diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. Blood 2003; 101: 78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Montoto S, Lopez‐Guillermo A, Colomer D et al. Incidence and clinical significance of Bcl‐2/Igh rearrangements in follicular lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2003; 44: 71–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lopez‐Guillermo A, Cabanillas F, McDonnell TI et al. Correlation of bcl‐2 rearrangement with clinical characteristics and outcome in indolent follicular lymphomas. Blood 1999; 93: 3081–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huang JZ, Sanger WG, Greiner TC et al. The t(14;18) defines a unique subset of diffuse large B–cell lymphoma with a germinal center B‐cell gene expression profile. Blood 2002; 99: 2285–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rosenwald A, Wright G, Chan WC et al. Lymphoma/Leukemia Molecular Profiling Project . The use of molecular profiling to predict survival after chemotherapy for diffuse large‐B‐cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 1937–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Solal‐Celigny P, Roy P, Colombat P et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index. Blood 2004; 104: 1258–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mirza I, Macpherson N, Paproski S et al. Primary cutaneous follicular lymphoma: an assessment of clinical, histopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular features. J Clin Oncol; 20: 647–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 1958; 53: 457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 27. MacPartlin M, Zeng S, Lee H. et al. p300 regulates p63 transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem 2005; 280: 30604–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zigeuner R, Tsybrovskyy O, Ratschek M, Rehak P, Lipsky K, Langner C. Prognostic impact of p63 and p53 expression in upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma. Urology 2004; 63: 1079–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Massion PP, Taflan PM, Jamshedur Rahman SM et al. Significance of p63 amplification and overexpression in lung cancer development and prognosis. Cancer Res 2003; 63: 7113–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hedvat CV, Teruya‐Feldstein J, Puig P et al. Expression of p63 in diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2005; 13: 237–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]