Abstract

Hepatic artery ligation (HAL), transarterial embolization (TAE), and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) have been treatment choices for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Obstruction of tumor blood supply is one of the most important mechanisms of these therapeutics measures. Here we introduced HAL into a metastatic human HCC orthotopic nude mouse model (using MHCC97L and HepG2 cell lines) to examine the effects of hepatic blood flow obstruction on the metastatic potential of hepatic tumor cells, and to investigate the mechanisms underlying these effects. Our results indicated that HAL inhibited tumor growth but concomitantly elicited tumor adaptation and progression, with increased potential for invasion and distant metastases. The underlying proinvasive mechanism of HAL appeared to be associated with enhanced intratumoral hypoxia and epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) due to hypoxia. This was in accord with the in vitro response of MHCC97L and HepG2 cells to hypoxia. The therapeutic effects of HAL could be enhanced by the phosphatidyl inositol 3‐kinase (PI3K) inhibitor LY294002, through arrest of EMT in hepatic tumor cells. It could be useful in the development of mechanism‐based combination therapies to enhance the initial antitumor response. (Cancer Sci 2009)

Rooted in the belief that blocking vessel supply starves tumors to death,( 1 ) multiple strategies for obstruction of hepatic arterial blood flow have achieved a pronounced therapeutic effect for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), especially unresectable HCC.( 2 , 3 ) These measures include hepatic artery ligation (HAL), transarterial embolization (TAE), and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE). To some extent, recent rising antiangiogenic therapies such as sorafenib also develop conceptually from this theory.( 2 , 4 ) Although overall survival of most patients was prolonged after treatment, this success was transient, without offering enduring cure. In some cases, a higher incidence of pulmonary metastasis has been reported following hepatic artery occlusion.( 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ) However, the precise mechanisms responsible for treatment failure are not yet clear.

One plausible mechanism is hypoxia, one of the most prominent antitumor approaches, which works by blocking vessel supply. It has been noted that although hypoxia kills most tumor cells, it provides a strong selective pressure for the survival of the most aggressive and metastatic cells.( 9 ) Such cells are proficient at escaping the noxious hypoxic microenvironment by activation of an invasive epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and other metastatic programs, ultimately leading to tumor recurrence or metastasis.( 10 ) The majority of preclinical studies have focused on the significance of angiogenesis due to hypoxia on the enhanced malignant potential of HCC after blocking vessel supply,( 11 , 12 , 13 ) but less attention has been paid to the tumor cells themselves. It is possible that the process of EMT could account for proinvasive consequences, since it is one of the central mechanisms involved in invasion and metastasis.( 14 ) EMT results in the morphologic and molecular changes of transformed cells, characterized by the loss of epithelial traits and the acquisition of traits characteristic of mesenchymal cells. In addition to breast, renal, pancreatic, and colon carcinoma, an activated EMT program was recently demonstrated by Yan et al. and Cannito et al. in hypoxic hepatic tumor cells,( 15 , 16 ) where it was found to correlate with increased capacities for migration and invasion. It is therefore tempting to explore the significance of EMT on the metastatic potential of HCC following hepatic artery occlusion.

Studies of the histological and molecular changes occurring in HCC following hepatic artery occlusion have been hindered by the difficulties in obtaining clinical samples, and most studies have therefore been performed using animal models.( 17 , 18 ) However, these studies have either focused on non‐human tumors or have used ‘‘experimental metastasis,’’ so failing to account for the human background of the transformed cells, or the changes taking place during the initial steps of the invasion‐metastasis cascade.( 19 ) In this study, we introduced HAL into a metastatic human HCC orthotopic nude mouse model and examined if tumor blood flow blockage enhanced the metastatic potential of the residual HCC. We also investigated the mechanisms underlying the effects of HAL on HCC.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture. HepG2 cells (low‐metastatic human HCC cell line; American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD, USA) and MHCC97L cells (human HCC cell line with moderate metastatic potential, established at the Liver Cancer Institute,( 20 ) Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China) were used in this study. The cells were deprived of O2 and cultured under hypoxic conditions (1% O2, 5% CO2, and 94% N2) for at least 4 days. Cells maintained under normoxic conditions (20% O2, 5% CO2, and 75% N2) were used as controls. The stable red fluorescent protein (RFP)‐expressing MHCC97L‐R and HepG2‐R cell lines, derived from MHCC97L and HepG2 cells, respectively, were kindly provided by Dr W.Z. Wu [Liver Cancer Institute, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China( 21 )], and were used for in vivo experiments.

Animals. Male BALB/c nu/nu mice at 4–6 weeks of age, and weighing around 20 g, were obtained from the Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Science, and maintained under specific pathogen‐free conditions. The experimental protocol was approved by the Shanghai Medical Experimental Animal Care Commission.

Metastatic model of human HCC in nude mice and HAL. The human HCC orthotopic nude mouse models with MHCC97L or HepG2 cells were established, respectively, as previously described.( 20 ) Two weeks after orthotopic implantation, HAL was performed by ligating the main branch of the hepatic artery under an operating microscope (n = 106). Sham‐operated mice underwent laparotomy with exposure of the liver and dissection of the vascular structures, but without interruption of the hepatic blood flow (n = 46). Preliminary results suggested that HAL enhanced intratumoral hypoxia in this model by the enhanced expression of hypoxia‐inducible factor (HIF)‐1α and the augmented positive stain of pimonidazole (Supporting information Fig. S1 and S5).

Experimental groups. To evaluate the effects of HAL on tumor growth, distant metastasis, and survival, 72 nude mice bearing xenografts were randomly divided into a sham‐operated group (n MHCC97L = 18, n HepG2 = 18) and a HAL group (n MHCC97L = 18, n HepG2 = 18). Six weeks after orthotopic implantation, 12 nude mice from each group were randomly sacrificed to investigate tumor growth and distant metastasis. The remaining mice were maintained until they became tabescent and kyphotic.

In order to enhance the antitumor effects of HAL, LY294002 (a selective phosphatidyl inositol 3‐kinase (PI3K) inhibitor; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was used as described previously.( 22 ) Animals with MHCC97L (n = 10) or HepG2 (n = 10) xenografts underwent HAL and were subsequently injected intraperitoneally with LY294002 (100 μg/g body weight) thrice weekly. Corresponding control animals that underwent HAL (n MHCC97L = 10, n HepG2 = 10) were injected with an equal volume of vehicle (DMSO + 0.9% sodium chloride [NS]). Therapy began on the day after HAL and continued for 4 weeks. All mice were killed by cervical dislocation 48 h after the final treatment. Survival time was recorded as the time between the day of tumor inoculation and the day of death, and was assessed in five animals in each group.

Tumor growth and macroscopic metastases were further observed using fluorescence imaging. MHCC97L‐R and HepG2‐R xenograft model nude mice (n MHCC97L = 20, n HepG2 = 20) were established and divided respectively into four groups, as described above. Each group included five animals and was maintained for 6 weeks.

Parameters assessed. The largest (a) and smallest (b) tumor diameters were measured at necropsy, and the tumor volume was calculated as V = ab2/2.( 23 ) The lung metastasis and peritoneal seeding of MHCC97L‐R or HepG2‐R cells was visualized using fluorescence stereomicroscopy (Leica Microsystems Imaging Solutions, Cambridge, UK) and the integrated optical density (IOD) of the tumor fluorescence was quantitated by Image Pro Plus software.( 21 ) The orthotopic tumor and metastasis in the liver and lung were resected for histopathological studies.( 20 )

Cell growth and apoptosis in vitro. Cells (5 × 102 per well) were seeded in triplicate in 96‐well microplates and incubated under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. After 24 h, cell proliferation was determined in triplicate using a Cell Counting Kit‐8 (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), every day for 5 days. The results are expressed as corrected absorbance, which represents the actual absorbance of each well recorded at 570 nm.

An annexin‐V assay was used to assess cell apoptosis. Treated cells were incubated with 10 μL propidium iodide and 5 μL fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) annexin‐V (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) at room temperature for 15 min. Cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL, USA) and apoptotic cells were stained with annexin‐V.

Transwell invasion assay. Invasion assays were performed in 24‐well BioCoat Matrigel Invasion Chambers (Corning, Cambridge, MA, UK) using 1 × 105 cells in serum‐free DMEM and plated onto Matrigel‐coated filters. Conditioned medium supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum and NIH/3T3‐conditioned medium (1:1) were placed in the lower chambers as chemoattractants. After 72 h under hypoxic or normoxic culture conditions, cells that migrated to the underside of the membrane were stained with Giemsa (Sigma) and counted at ×200 magnification under a microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Real‐time quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR). Total RNA was isolated from the cultured cells or tumor tissues using Trizol reagent, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScript first strand synthesis system (Invitrogen). Portions of double‐stranded cDNA were subjected to PCR with a SYBR Green PCR kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The amplification protocol comprised incubations at 94°C for 15 s, 63°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s. Incorporation of the SYBR Green dye into PCR products was monitored in real time using an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), thereby allowing determination of the threshold cycle (CT) at which exponential amplification of the products began. The amount of target cDNAs relative to that of β‐actin cDNA was calculated from the CT values using Sequence Detector version 1.6.3 software (PE Applied Biosystems) The target cDNA was then amplified by PCR with Snail, Slug, and Twist primers: Snail‐f, 5′‐TGCAGGACTCTAATCCAAGTTTACC‐3′ and Snail‐r, 5′‐GTGGGATGGCTGCCAGC‐3′; Slug‐f, 5′‐GGTCAAGAAGCATTTCAAC‐3′ and Slug‐r, 5′‐CTGAGCCACTGTGGTCCTTG‐3′; Twist‐f, 5′‐TGTCCGCGTCCCACTAGC‐3′ and Twist‐r, 5′‐TGTCCATTTTCTCCTTCTCTGGA‐3′.

Immunoblotting and immunostaining assays. After the animals were killed, half of the tumor tissues were snap‐frozen in liquid nitrogen, and the other half were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin wax. The levels of E‐cadherin, vimentin, N‐cadherin, and Twist proteins in tumor tissues or cell specimens were determined using a standard immunoblotting protocol using 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.( 24 ) Monoclonal mouse antihuman vimentin antibodies (Sigma), monoclonal mouse antihuman E‐cadherin, N‐cadherin, and polyclonal mouse antihuman Twist antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) were used.

The formalin‐fixed and paraffin‐embedded tissue was cut into 4‐μm‐thick sections for histological studies using hematoxylin–eosin staining and immunostaining of Ki67 (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), E‐cadherin, N‐cadherin, Twist, and type I collagen (Dako).

Immunofluorescence and image analysis. Cultured cells were grown on slides and then washed and fixed. Cells were then incubated with primary antibodies to E‐cadherin, N‐cadherin, and vimentin (1:50 dilution), and antimouse and/or ‐rabbit FITC‐ and/or tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate–conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen). The fluorescent images were visualized using a confocal microscope (FV‐1000; Olympus).

Statistical analysis. Continuous variables were expressed as the median and range. The Mann‐Whitney U‐test was used for statistical comparisons. χ2‐tests were used to compare binary variables. The Kaplan–Meier method with log‐rank test was used for survival analysis. Significance was defined as P < 0.05. Calculations were made using SPSS software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

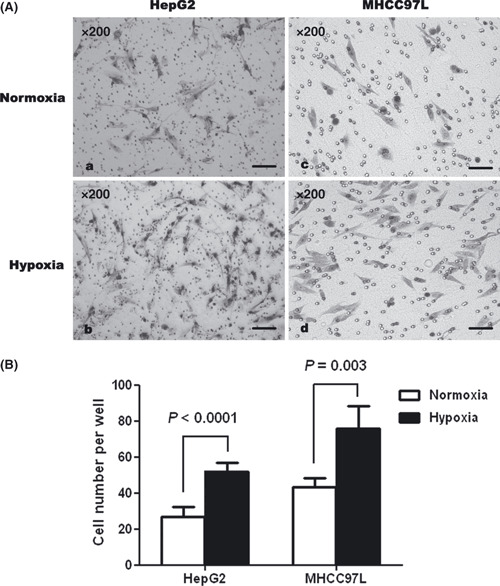

Hypoxia promoted invasiveness of hepatic tumor cells in vitro. An in vitro invasion assay showed the number of invasive hypoxic MHCC97L cells as 75.8 ± 12.7, which was dramatically higher than the number of normoxic MHCC97L cells (43.3 ± 4.9, P = 0.003). Similarly, the number of invasive normoxic HepG2 cells was 26.7 ± 5.5, which was significantly lower than the number of hypoxic HepG2 cells (52.0 ± 4.6, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1A,B).

Figure 1.

Hypoxia enhanced the invasiveness of MHCC97L and HepG2 cells in vitro in Transwell assays, compared with normoxic controls.

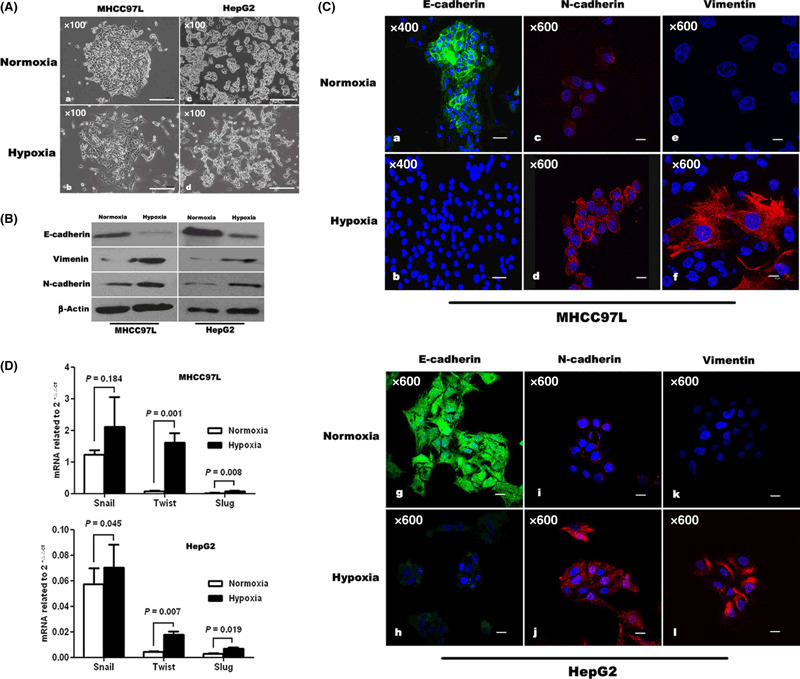

Hypoxia elicited EMT in hepatic tumor cells. The arrest of proliferation of hypoxic cells was achieved without augmentation of apoptosis (Supporting information Fig. S2). Four days after initiation of hypoxia, the morphologies of MHCC97L and HepG2 cells were altered from a typical epithelial cobblestone appearance to an elongated/irregular fibroblastoid shape (Fig. 2A). Accompanying these phenotypic changes, immunoblotting demonstrated a reduction in the expression of the epithelial cell marker E‐cadherin in these hypoxic cells, relative to the normoxic control cells. At the same time, the levels of the mesenchymal cell markers vimentin and N‐cadherin were increased (Fig. 2B). The so‐called ‘cadherin switch,’( 25 ) characterized by the loss of E‐cadherin expression and the simultaneous up‐regulation of N‐cadherin, was also detected by immunofluorescence in both cell lines in response to hypoxia (Fig. 2C). Additionally, real‐time RT‐PCR showed a trend toward increase of the transcription factors Snail, Slug, and Twist mRNA in hypoxic cells (compared with those of the respective normoxic controls). Among these, the amplification of Twist and Slug mRNA were both statistically significant (P < 0.05; Fig. 2D) in two cell lines.

Figure 2.

Hypoxia induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) in MHCC97L and HepG2 cells. (A) Morphologic changes consistent with EMT (spindle‐shaped cells with loss of polarity and increased intercellular separation) were observed in MHCC97L and HepG2 cells under hypoxic conditions, compared with corresponding normoxic cells. Immunoblotting (B) and immunofluorescence staining (C) showed that MHCC97L and HepG2 cells exhibited changes in cellular EMT markers in response to hypoxia as characterized by down‐regulation of E‐cadherin and up‐regulation of N‐cadherin and vimentin, compared with controls. (D) Quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction showed a trend towards enhanced expression of transcription factors Snail, Slug, and Twist at the mRNA level in hypoxic cells. In both cell lines, the up‐regulation of Twist and Slug mRNA reached statistical significance.

HAL inhibited tumor growth but promoted invasiveness and distant metastasis. After HAL, the tumor size of MHCC97L‐ and HepG2‐derived xenografts were 1996.81 ± 223.68 mm3 and 2820.72 ± 528.83 mm3 respectively, which were both smaller than those of the matched sham‐operated controls (4049.16 ± 596.52 mm3 in MHCC97L xenografts and 4608.79 ± 963.13 mm3 in HepG2 xenografts [P < 0.05]). It was evident in both xenografts that impaired tumor growth was correlated with a pronounced decrease in Ki67‐positive staining of residual tumors (Supporting information Fig. S3b,d).

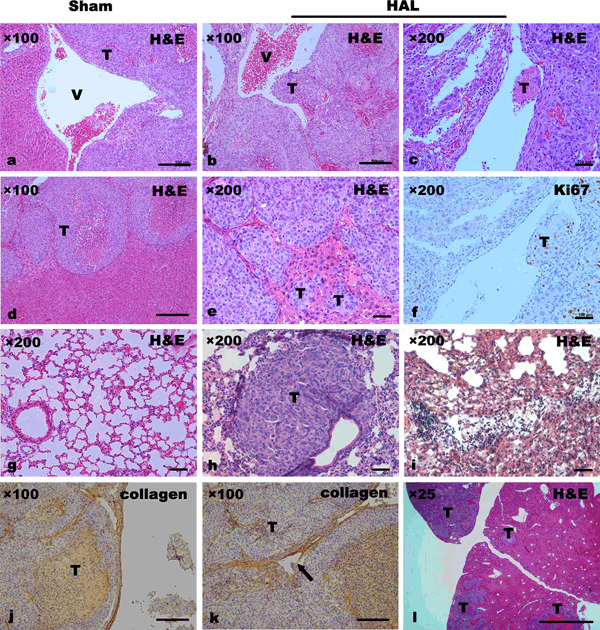

However, in MHCC97L‐R xenografts, bioluminescence showed that HAL promoted microscopic intrahepatic dissemination (Supporting information Fig. S4b), peritoneal seeding (Supporting information Fig. S4d), and lung metastasis (Supporting information Fig. S4f) of tumors. Also the proinvasive consequences of HAL appeared in animals bearing MHCC97L xenografts. Histological analyses revealed that the primary tumor in HAL‐treated mice had a much thinner capsule, with areas of breakage, or the capsule was completely absent, whereas the majority of control tumors were predominantly encapsulated or had thicker capsules (Fig. 3d,j). Venous invasion (Fig. 3b) and tumor thrombi (Fig. 3c) were also significantly more common in the xenografts in HAL‐treated mice, and the tumor thrombi showed Ki67‐positive staining (Fig. 3f). Congruently, primary tumor exhibited a pronounced local invasion (Fig. 3e) and intrahepatic dissemination (Fig. 3l). Analysis of serial lung sections indicated a significantly higher incidence of pulmonary metastasis in HAL‐treated mice compared with that in sham‐operated mice (10/12 vs 4/12, P = 0.036) and the numbers of pulmonary metastatic foci in each mouse were 66.1 ± 15.6 versus 49.3 ± 6.8 (P = 0.016). Notably, the lungs of HAL‐treated mice showed more inflammatory damage, compared with sham‐operated controls (Fig. 3g), characterized by intense inflammatory infiltration, thickening of alveolar walls, and severe vascular margination (Fig. 3i). In contrast to that of the MHCC97L, the induction of local invasion by HAL was not evident in HepG2 xenografts, except for capsule encroachment (Fig. 3k). Using bioluminescence, animals with HepG2‐R xenografts showed enhanced intrahepatic dissemination (Supporting information Fig. S4h) and increased peritoneal seeding (Supporting information Fig. S4j) after HAL, but without visible pulmonary metastasis (Supporting information Fig. S4l).

Figure 3.

Hepatic artery ligation (HAL) promoted the invasive and metastatic potential of MHCC97L and HepG2 xenografts. Histological analysis of primary tumor and lung by H&E staining showed that malignant intravasation, such as venous invasion (b) and tumor thrombus formation (c,f), was mostly observed in HAL‐treated mice with MHCC97L xenografts, compared with sham‐operated controls (a). Immunostaining of type I collagen revealed much thinner capsules with areas of capsule breakage in tumors of HAL‐treated mice with both xenografts (k). Moreover, multiple intrahepatic (l) and pulmonary metastatic tumor nodules (h), and more severe inflammatory lung injuries (i) were present in nude mice with MHCC97L xenografts receiving HAL. T, tumor; V, vein. Arrow, breakage of capsule.

The mean survival times of the MHCC97L‐bearing mice were similar between the two groups (56.0 ± 4.6 days in the HAL group vs 60.7 ± 5.8 days in the sham‐operated group, P = 0.153). Also no significant difference was observed in animals with HepG2 xenografts, regardless of receiving HAL or not.

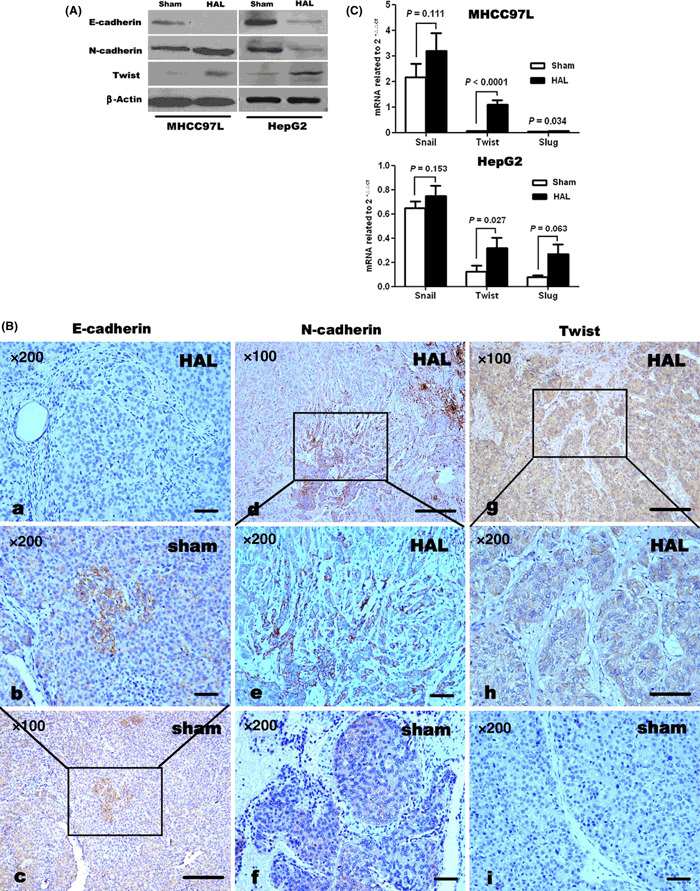

HAL induced changes consistent with EMT in HCC xenografts. Induction of EMT by HAL was demonstrated in MHCC97L and HepG2 xenografts by immunoblotting, characterized by the loss of E‐cadherin and up‐regulation of N‐cadherin in the tumor tissues of HAL‐treated mice (Fig. 4A). Immunostaining showed that E‐cadherin‐positive cells in sham‐operated mice were localized in the central tumor areas and showed a membranous distribution (Fig. 4Bb,c), while N‐cadherin‐positive cells were found at the invasive fronts and interspersed with the stroma (Fig. 4Bd,e). Additionally, mRNA expression of Snail, Slug, and Twist were examined in tumor tissues using real‐time RT‐PCR and revealed a trend towards enhanced expression of all transcription factors in HAL‐treated mice, compared with corresponding sham‐operated mice (Fig. 4C). However, only the augmentation of Twist mRNA reached statistical significance in both xenografts, compared with those of matched sham‐operated controls (P < 0.05), as well as with other transcriptional factors.

Figure 4.

Hepatic artery ligation (HAL) induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition in MHCC97L and HepG2 xenografts. Immunoblotting (A) and immunostaining (B) revealed that E‐cadherin protein expression was decreased by HAL, while the protein levels of N‐cadherin and Twist in tumor tissues were higher in HAL‐treated mice than in sham‐operated controls. Immunostaining also showed that E‐cadherin‐positive cells were localized in central tumor areas (Bc) but N‐cadherin‐positive tumor cells were more concentrated at the invasive fronts (Bd). Both showed a membranous distribution (Bb,e). (C) Quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction showed a trend towards enhanced expression of transcription factors Snail, Slug, and Twist at the mRNA level. However, only Twist mRNAs were significantly up‐regulated in both xenografts.

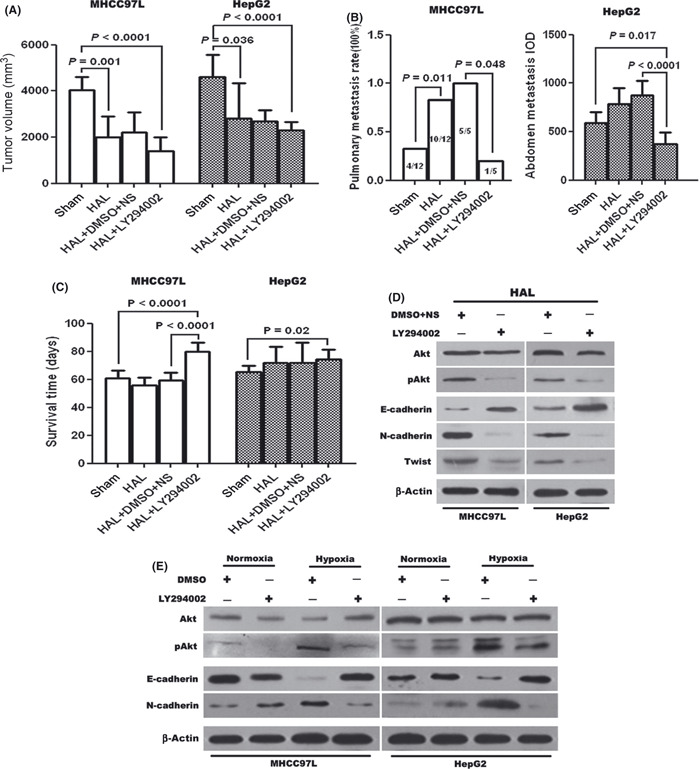

LY294002 inhibited peritoneal seeding and pulmonary metastases following HAL through arrest of EMT. Because LY294002 could inhibit the hypoxia‐induced EMT in HCC cells in vitro,( 15 ) it was systemically administrated to HAL‐treated mice. After treatment by LY294002, the tumor size of MHCC97L xenografts was 1506.33 ± 680.56 mm3, which was slightly smaller than that of DMSO + NS controls (2213.38 ± 877.37 mm3, P = 0.15). However, the pulmonary metastasis rates and metastatic tumor clusters per mouse were 0% (0/5) and 0 in LY294002‐treated mice, which both were significantly less than that of DMSO + NS‐treated mice (100% [5/5] and 75 ± 14.5, P < 0.05), respectively. Congruently, the lifespan of LY294002‐treated mice was prolonged; it was 85.8 ± 9.6 days, compared with 59.3 ± 6.9 days in the control (P < 0.0001). Similar trends toward reduction of tumor size (2285.89 ± 388.29 mm3 vs 2682.9 ± 494.18 mm3, P = 0.153), suppression of peritoneal seeding (P < 0.0001), and prolongation of survival (70.7 ± 5.5 days vs 59.2 ± 5.9 days, P = 0.006) were also observed in LY294002‐treated mice with HepG2 xenografts, compared with those of DMSO + NS‐treated mice.

To further determine if LY294002 inhibited specific molecular changes consistent with EMT, residual tumor tissues lysates of HAL‐treated mice from the test and control groups were subjected to immunoblotting. As shown in Figure 5D, the down‐regulation of N‐cadherin expression and up‐regulation of E‐cadherin were achieved by treatment of LY294002. In the same mice, the reduction of phospho‐Akt (p‐Akt) expression also appeared without any change in the total amount of Akt. The arrest of EMT by LY294002 in HAL‐treated xenografts was further demonstrated by the in vitro response of both cells to LY294002. As shown in Figure 5E, LY294002 caused a complete or partial shift of EMT markers back to the pre‐hypoxic state.

Figure 5.

LY294002 enhanced the therapeutic effects of hepatic artery ligation (HAL) in the hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) model. Combination of HAL and LY294002 significantly inhibited tumor growth (A) and distant metastases (B), resulting in prolongation of survival of mice bearing xenografts (C). Immunoblotting revealed the effects of LY294002 on the protein expression of Akt, phospho‐Akt, E‐cadherin, N‐cadherin, and Twist in tumor tissues (D) and cell specimens (E), and revealed that both in vitro and in vivo, LY294002 remarkably repressed the induction of epithelial–mesenchymal transition in HCC cells by hypoxia, as well as the increase of phospho‐Akt.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated the significance of hepatic artery occlusion on tumor growth and invasiveness in a metastatic human HCC orthotopic nude mouse model. Although the xenograft volumes were reduced after blocking the blood supply, the residual tumors were more invasive in HAL‐treated mice. This observation supports the link between intratumoral hypoxia and EMT of tumor cells. LY294002 repressed hypoxia‐induced EMT in HCC cells in vitro or in vivo, and in combination with HAL could significantly reduce metastasis and prolong lifespan.

In most cases, cancer patients die as a result of metastasis, rather than primary tumor growth.( 26 ) However, the majority of previous clinical studies of blocking vessel supply have focused on the effects of therapy on primary tumor growth, with less attention on metastasis. The therapeutic significance of failure of blocking vessel supply is uncertain. Heightened invasion has recently been implicated as a response to hepatic artery occlusion in several animal models of orthotopic VX2,( 27 ) walker‐256,( 12 ) and NF13762 murine breast tumor,( 11 ) in which angiogenesis and revascularization of the tumor tissues was more distinct, and so favored intravasation of tumor cells. In this study, we introduced HAL into the human HCC orthotopic nude mouse model (using MHCC97L and HepG2 cells) and demonstrated that therapeutically efficacious blockage of the blood flow could elicit an adaptive–evasive response from hepatic tumor cells, involving an augmented invasive phenotype, with encroachment on the capsule, maligant intravasation, increased dissemination, and the emergence of distant metastasis.

The results of previous studies using some animal cancer models have suggested that metastasis correlates closely with tumor burden, that is the bigger the tumor, the more malignant cells can escape and hence the larger the metastatic burden. Metastasis was also inhibited by effective therapy after resection of primary tumors. However, the results of the current study using this HCC model support the opposite conclusion, and suggested that obstruction of the hepatic artery inhibited primary tumor growth but concomitantly promoted tumor invasiveness and metastasis. The reasons for these discrepancies remain speculative, but it is possible that the hypoxia/HIF‐1α pathway plays a key role in HAL‐induced invasion and metastasis. It has been shown that the exacerbated proinvasive phenotype of HCC xenografts correlated with enhanced intratumoral hypoxia after hepatic artery occlusion, as seen in vitro, where the invasiveness of MHCC97L and HepG2 cells increased in response to hypoxia. In addition, several studies in other models have also implied that hypoxia caused by hepatic blood flow blockage induced angiogenesis and hence promoted malignant potential of tumors via HIF‐1α activation.( 11 , 12 , 13 ) Notably, obstruction of the hepatic artery induced EMT in hepatic tumor cells in our study, which would also lead to more invasive and/or metastatic phenotypes, and has been linked to the hypoxia response.( 28 )

EMT, as one of the major biological effects of hypoxia, plays a significant role in a number of pathological states, including tumor metastasis and organic fibrosis.( 14 ) On the basis of previous in vitro studies of EMT in hypoxic ovarian, breast, renal, and hepatic tumor cells, we demonstrated for the first time that EMT contributes to the phenotypic progression of HCC after hepatic blood flow blockage. E‐cadherin protein, a marker of EMT, was down‐regulated in tumor tissues receiving HAL. This was consistent with the clinical evidence obtained by Adachi et al.,( 29 ) which showed that TAE inhibited E‐cadherin expression in HCC. Moreover, the location of the E‐cadherin‐positive tumor cells in the central areas of the xenografts and their absence at the invasive fronts suggests that E‐cadherin expression is not involved in the invasiveness of HCC. Second, N‐cadherin, a mesenchymal cell marker, was expressed throughout the hypoxia‐associated cancer progression and was highly expressed in tumor tissues of HAL‐treated mice. N‐cadherin‐positive cells were found at the invasive fronts and were interspersed with the stroma. Notably, the ‘cadherin switch’ triggered by hypoxia in vitro was also significant in the xenografts in HAL‐treated mice. Third, there was a trend towards the up‐regulation of transcription factors related to EMT (e.g. Snail, Slug, and Twist) in hypoxic‐HCC cells and HAL‐treated xenografts. Twist mRNA, particularly, was both augmented in vitro and in vivo under hypoxic conditions. Based on recent evidence from Yang et al., who showed that HIF‐1α directly regulated Twist and promoted tumor metastasis,( 28 ) we postulate that Twist plays an essential role in the proinvasive consequences of HAL. Fourth, as mentioned above, the intriguing association between arrest of proliferation in residual cancer cells after HAL and enhanced invasive potential is a major feature of EMT,( 30 ) and may be associated with dedifferentiation of these cells and their progression to stages of greater malignancy, including cancer stem cell–like transformation.( 31 , 32 ) Finally, consistent with previous in vitro results that LY294002 inhibited hypoxia‐induced EMT in HCC cells,( 15 ) here we demonstrated that LY294002 also repressed the enhanced metastatic potential in HAL‐treated mice by arresting EMT. This not only has implications for the role of EMT in HCC progression, but also raises the possibility that inhibition of EMT could enhance the initial effects of hepatic blood flow blockage. It is possible that other therapy‐induced mechanisms could contribute to the phenotypic progression of malignancy, and further studies are needed in this area.

Although the current study used an animal model, its results could be of general importance for many clinical trials. On one hand, the proinvasive consequences of hepatic artery occlusion demonstrated in our model might offset the antitumor response and even worsen the outcome in some cases. In this regard, randomized, controlled clinical trials have failed to demonstrate any significant effect of preoperative TACE on the disease‐free survival of patients with early stage HCC after hepatectomy.( 3 ) In patients with inoperable HCC, clinical experience has revealed that therapeutically efficacious blocking vessel supply often prolongs overall survival by only months [although a median survival of 20 months is expected( 2 )], without offering a long‐term cure. The increased progression‐free survival implied by Paez‐Ribes et al. likely reflected the initial impairment of primary tumor growth, but this effect was short lived, with the subsequent onset of multiple forms of resistance inevitably leading to a return to progressive disease.( 8 ) Another clinically relevant result of the current study was that concomitant use of other therapeutics, together with hepatic artery occlusion, could alter or even abrogate the increased malignant phenotype: administration of LY294002 following HAL inhibited the enhanced malignant potential of HCC. We therefore postulate that combination therapy with HAL and an antimetastatic agent could act synergistically to overcome the prometastatic effects of blocking blood flow (such as interferon‐α, Supporting information Fig. S7 and S8). Although the synergistic benefit at present is only confirmed with a few chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin,( 2 , 3 ) it highlights the essentiality of testing new therapeutic strategies involving mechanism‐based drugs in combination as a possible approach to abrogate the adverse effect.

Overall, the results of this study using an HCC model shed new light on the proinvasive consequences of blocking vessel supply and suggest a significant role for hypoxia, and EMT caused by hypoxia, in these effects. Further preclinical studies are warranted to clarify the mechanisms responsible for this adaptive–evasive resistance, in order to help with the design and testing of mechanism‐based combination therapies or new therapeutic regimes to enhance the initial response of HCC to HAL.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. Analysis of expression of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)‐1α and pimonidazole staining in xenografts. Immunostaining (Aa,b) and immunoblotting (B) for HIF‐1α revealed that hepatic artery ligation significantly increased intratumoral hypoxia, compared with sham‐operated mice. Similar results were noted when pimonidazole‐positive cells in xenografts were examined by immunostaining (Ac,d, and C).

Fig. S2. (a) Analysis of proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells showed that hypoxia inhibited cell proliferation compared with normoxic controls. (b) Representative fluorescence‐activated cell sorting histograms revealed no significant difference in apoptotic rates between hypoxic and normoxic HCC cells.

Fig. S3. (a,c) Comparison of volumes of xenografts at 4 weeks after sham‐operation or hepatic artery ligation (HAL) suggested that HAL significantly inhibited tumor growth. (b,d) Tumor cell proliferation was demonstrated by Ki67 staining and the percentage of Ki67‐positive cells was dramatically reduced after HAL.

Fig. S4. Bioluminescence showed increased microscopic intrahepatic dissemination, peritoneal seeding, and pulmonary metastasis in hepatic artery ligation–treated mice, whether bearing MHCC97L or HepG2 xenografts, compared with corresponding sham‐operated controls.

Fig. S5. Immunostaining analysis of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)‐1α expression and pimonidazole staining in tumor and peritumoral tissues. Consistent with augmentation of intratumoral hypoxia, peritumoral hypoxia was also increased by hepatic artery ligation (h, i, k, l), compared with sham‐operation (b, c, e, f). However, the degree of hypoxia in peritumoral tissues was lower than that in tumor tissues. NT, nontumoral tissue; T, tumor.

Fig. S6. Immunostaining analysis of molecular changes consistent with epithelial–mesenchymal transition in peritumoral tissues. It was revealed that the expression of E‐cadherin in peritumoral tissues was down‐regulated by hepatic artery ligation (HAL) (k,h), compared with sham‐operated controls (b,e), while the expression of N‐cadherin was up‐regulated after HAL (i,l). NT, nontumoral tissue; T, tumor.

Fig. S7. Interferon (IFN)‐α enhanced the therapeutic effects of hepatic artery ligation in a hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) model. (a) Volumes of orthotopic tumor at 6 weeks were compared and significant inhibition of tumor growth was achieved in the group with high‐dose IFN‐α (1.5 × 107 U/kg). (b) Analysis of pulmonary metastatic rates in all groups suggested that there was a significant reduction of pulmonary metastasis in moderate‐ (7.5 × 106 U/kg) or high‐dose IFN‐α‐treated mice. (c) The survival curve of different treatment groups showed that a significant prolongation of lifespan was achieved by not only high‐dose IFN‐α, but also moderate‐dose IFN‐α, compared with 0.9% sodium chloride (NS) control. (d) Immunoblotting revealed the effects of different dose IFN‐α on the protein expression of E‐cadherin, N‐cadherin, and Twist in xenografts of HAL‐treated mice. Moderate or high IFN‐α remarkably decreased the expression of N‐cadherin and Twist, whereas E‐cadherin protein was only detectable in tumor tissues that received high‐dose IFN‐α. Notably, the expression of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)‐1α was unaffected by IFN‐α, even at a concentration of 1.5 × 107 U/kg.

Fig. S8. The proliferation and molecular changes in the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) of MHCC97L and HepG2 cells in response to interferon (IFN)‐α under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. (a,b) When the concentration of IFN‐α was 10 000 U/mL, the proliferation of normoxic‐MHCC97L, normoxic‐HepG2, and hypoxic‐HepG2 cells was significantly inhibited, while the growth of the hypoxic‐MHCC97L cells was unaffected by IFN‐α, even at a concentration of 100 000 U/mL. (c,d) When the concentration of IFN‐α was 10 000 U/mL, hypoxia‐induced EMT in both MHCC97L and HepG2 cells was inhibited, characterized by a complete or partial shift of EMT markers back to the pre‐hypoxic state.

Please note: Wiley‐Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Acknowledgment

This research project was supported by grants from the Foundation of China National ‘211’ Project for Higher Education (no. 2007‐353).

The first two authors contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1. Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N Engl J Med 1971; 285: 1182–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Llovet JM, Bruix J. Molecular targeted therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2008; 48: 1312–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2003; 362: 1907–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 378–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liou TC, Shih SC, Kao CR, Chou SY, Lin SC, Wang HY. Pulmonary metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma associated with transarterial chemoembolization. J Hepatol 1995; 23: 563–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Song BC, Chung YH, Kim JA et al. Association between insulin‐like growth factor‐2 and metastases after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study. Cancer 2001; 91: 2386–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ebos JM, Lee CR, Cruz‐Munoz W, Bjarnason GA, Christensen JG, Kerbel RS. Accelerated metastasis after short‐term treatment with a potent inhibitor of tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell 2009; 15: 232–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Paez‐Ribes M, Allen E, Hudock J et al. Antiangiogenic therapy elicits malignant progression of tumors to increased local invasion and distant metastasis. Cancer Cell 2009; 15: 220–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Graeber TG, Osmanian C, Jacks T et al. Hypoxia‐mediated selection of cells with diminished apoptotic potential in solid tumours. Nature 1996; 379: 88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brahimi‐Horn MC, Chiche J, Pouyssegur J. Hypoxia and cancer. J Mol Med 2007; 85: 1301–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gupta S, Kobayashi S, Phongkitkarun S, Broemeling LD, Kan Z. Effect of transcatheter hepatic arterial embolization on angiogenesis in an animal model. Invest Radiol 2006; 41: 516–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li X, Feng GS, Zheng CS, Zhuo CK, Liu X. Influence of transarterial chemoembolization on angiogenesis and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor in rat with Walker‐256 transplanted hepatoma: an experimental study. World J Gastroenterol 2003; 9: 2445–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liao XF, Yi JL, Li XR, Deng W, Yang ZF, Tian G. Angiogenesis in rabbit hepatic tumor after transcatheter arterial embolization. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10: 1885–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thiery JP. Epithelial–mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer 2002; 2: 442–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yan W, Fu Y, Tian D et al. PI3 kinase/Akt signaling mediates epithelial–mesenchymal transition in hypoxic hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009; 382: 631–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cannito S, Novo E, Compagnone A et al. Redox mechanisms switch on hypoxia‐dependent epithelial–mesenchymal transition in cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 2008; 29: 2267–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Van Der Bilt JD, Kranenburg O, Nijkamp MW et al. Ischemia/reperfusion accelerates the outgrowth of hepatic micrometastases in a highly standardized murine model. Hepatology 2005; 42: 165–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tamagawa K, Horiuchi T, Uchinami M et al. Hepatic ischemia‐reperfusion increases vascular endothelial growth factor and cancer growth in rats. J Surg Res 2008; 148: 158–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yang ZF, Poon RT, To J, Ho DW, Fan ST. The potential role of hypoxia inducible factor 1alpha in tumor progression after hypoxia and chemotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 5496–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tian J, Tang ZY, Ye SL et al. New human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cell line with highly metastatic potential (MHCC97) and its expressions of the factors associated with metastasis. Br J Cancer 1999; 81: 814–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang BW, Liang Y, Xia JL et al. Biological characteristics of fluorescent protein‐expressing human hepatocellular carcinoma xenograft model in nude mice. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 20: 1077–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hu L, Hofmann J, Jaffe RB. Phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase mediates angiogenesis and vascular permeability associated with ovarian carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11: 8208–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang L, Tang ZY, Qin LX et al. High‐dose and long‐term therapy with interferon‐alfa inhibits tumor growth and recurrence in nude mice bearing human hepatocellular carcinoma xenografts with high metastatic potential. Hepatology 2000; 32: 43–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ke AW, Shi GM, Zhou J et al. Role of overexpression of CD151 and/or c‐Met in predicting prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2009; 49: 491–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wheelock MJ, Shintani Y, Maeda M, Fukumoto Y, Johnson KR. Cadherin switching. J Cell Sci 2008; 121: 727–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gupta GP, Massague J. Cancer metastasis: building a framework. Cell 2006; 127: 679–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hong K, Kobeiter H, Georgiades CS, Torbenson MS, Geschwind JF. Effects of the type of embolization particles on carboplatin concentration in liver tumors after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in a rabbit model of liver cancer. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2005; 16: 1711–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yang MH, Wu MZ, Chiou SH et al. Direct regulation of TWIST by HIF‐1alpha promotes metastasis. Nat Cell Biol 2008; 10: 295–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Adachi E, Matsumata T, Nishizaki T, Hashimoto H, Tsuneyoshi M, Sugimachi K. Effects of preoperative transcatheter hepatic arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. The relationship between postoperative course and tumor necrosis. Cancer 1993; 72: 3593–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yang J, Weinberg RA. Epithelial–mesenchymal transition: at the crossroads of development and tumor metastasis. Dev Cell 2008; 14: 818–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ et al. The epithelial–mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell 2008; 133: 704–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Morel AP, Lievre M, Thomas C, Hinkal G, Ansieau S, Puisieux A. Generation of breast cancer stem cells through epithelial–mesenchymal transition. PLoS ONE 2008; 3: e2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Analysis of expression of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)‐1α and pimonidazole staining in xenografts. Immunostaining (Aa,b) and immunoblotting (B) for HIF‐1α revealed that hepatic artery ligation significantly increased intratumoral hypoxia, compared with sham‐operated mice. Similar results were noted when pimonidazole‐positive cells in xenografts were examined by immunostaining (Ac,d, and C).

Fig. S2. (a) Analysis of proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells showed that hypoxia inhibited cell proliferation compared with normoxic controls. (b) Representative fluorescence‐activated cell sorting histograms revealed no significant difference in apoptotic rates between hypoxic and normoxic HCC cells.

Fig. S3. (a,c) Comparison of volumes of xenografts at 4 weeks after sham‐operation or hepatic artery ligation (HAL) suggested that HAL significantly inhibited tumor growth. (b,d) Tumor cell proliferation was demonstrated by Ki67 staining and the percentage of Ki67‐positive cells was dramatically reduced after HAL.

Fig. S4. Bioluminescence showed increased microscopic intrahepatic dissemination, peritoneal seeding, and pulmonary metastasis in hepatic artery ligation–treated mice, whether bearing MHCC97L or HepG2 xenografts, compared with corresponding sham‐operated controls.

Fig. S5. Immunostaining analysis of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)‐1α expression and pimonidazole staining in tumor and peritumoral tissues. Consistent with augmentation of intratumoral hypoxia, peritumoral hypoxia was also increased by hepatic artery ligation (h, i, k, l), compared with sham‐operation (b, c, e, f). However, the degree of hypoxia in peritumoral tissues was lower than that in tumor tissues. NT, nontumoral tissue; T, tumor.

Fig. S6. Immunostaining analysis of molecular changes consistent with epithelial–mesenchymal transition in peritumoral tissues. It was revealed that the expression of E‐cadherin in peritumoral tissues was down‐regulated by hepatic artery ligation (HAL) (k,h), compared with sham‐operated controls (b,e), while the expression of N‐cadherin was up‐regulated after HAL (i,l). NT, nontumoral tissue; T, tumor.

Fig. S7. Interferon (IFN)‐α enhanced the therapeutic effects of hepatic artery ligation in a hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) model. (a) Volumes of orthotopic tumor at 6 weeks were compared and significant inhibition of tumor growth was achieved in the group with high‐dose IFN‐α (1.5 × 107 U/kg). (b) Analysis of pulmonary metastatic rates in all groups suggested that there was a significant reduction of pulmonary metastasis in moderate‐ (7.5 × 106 U/kg) or high‐dose IFN‐α‐treated mice. (c) The survival curve of different treatment groups showed that a significant prolongation of lifespan was achieved by not only high‐dose IFN‐α, but also moderate‐dose IFN‐α, compared with 0.9% sodium chloride (NS) control. (d) Immunoblotting revealed the effects of different dose IFN‐α on the protein expression of E‐cadherin, N‐cadherin, and Twist in xenografts of HAL‐treated mice. Moderate or high IFN‐α remarkably decreased the expression of N‐cadherin and Twist, whereas E‐cadherin protein was only detectable in tumor tissues that received high‐dose IFN‐α. Notably, the expression of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)‐1α was unaffected by IFN‐α, even at a concentration of 1.5 × 107 U/kg.

Fig. S8. The proliferation and molecular changes in the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) of MHCC97L and HepG2 cells in response to interferon (IFN)‐α under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. (a,b) When the concentration of IFN‐α was 10 000 U/mL, the proliferation of normoxic‐MHCC97L, normoxic‐HepG2, and hypoxic‐HepG2 cells was significantly inhibited, while the growth of the hypoxic‐MHCC97L cells was unaffected by IFN‐α, even at a concentration of 100 000 U/mL. (c,d) When the concentration of IFN‐α was 10 000 U/mL, hypoxia‐induced EMT in both MHCC97L and HepG2 cells was inhibited, characterized by a complete or partial shift of EMT markers back to the pre‐hypoxic state.

Please note: Wiley‐Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item