Abstract

To develop peptide‐based immunotherapy for osteosarcoma, we previously identified papillomavirus binding factor (PBF) as a cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL)‐defined osteosarcoma antigen in the context of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)‐B55. In the present study, we analyzed the distribution profile of PBF in 83 biopsy specimens of osteosarcomas and also the prognostic impact of PBF expression in 78 patients with osteosarcoma who had completed the standard treatment protocols. Next, we determined the antigenic peptides from PBF that react with peripheral T lymphocytes of HLA‐A24+ patients with osteosarcoma. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that 92% of biopsy specimens of osteosarcoma expressed PBF. PBF‐positive osteosarcoma conferred significantly poorer prognosis than those with negative expression of PBF (P = 0.025). In accordance with the Bioinformatics and Molecular Analysis Section score, we synthesized 10 peptides from the PBF sequence. Subsequent screening with an HLA class I stabilization assay revealed that peptide PBF A24.2 had the highest affinity to HLA‐A24. CD8+ T cells reacting with a PBF A24.2 peptide were detected in eight of nine HLA‐A24‐positive patients with osteosarcoma at the frequency from 5 × 10−7 to 7 × 10−6 using limiting dilution/mixed lymphocyte peptide culture followed by tetramer‐based frequency analysis. PBF A24.2 peptide induced CTL lines from an HLA‐A24‐positive patient, which specifically killed an osteosarcoma cell line that expresses both PBF and HLA‐A24. These findings suggested prognostic significance and immunodominancy of PBF in patients with osteosarcoma. PBF is the candidate target for immunotherapy in patients with osteosarcoma. (Cancer Sci 2008; 99: 368–375)

Osteosarcoma is the most common primary malignant tumor of bone. The past three decades have witnessed remarkable advances in the treatment of osteosarcoma. These include the introduction of adjuvant chemotherapy, establishment of guidelines for adequate surgical margins, and the development of postexcision reconstruction.( 1 , 2 ) There have also been advances in the field of immunotherapy for osteosarcoma that, unfortunately, have received less attention.( 3 , 4 ) However, the current stagnation in chemotherapy‐based treatments for osteosarcoma has reignited interest in immunotherapeutic approaches.( 5 , 6 )

Recent immunotherapy depends largely on understanding of the molecular interactions between T cell receptors (TCR) on cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) and antigenic peptides on tumor cells. This has led to a variety of vaccination approaches, including those with antigenic peptides( 7 ) recombinant viruses encoding antigenic genes( 8 ) dendritic cells( 9 ) and T lymphocytes, in which the TCR recognizing an antigenic peptide is genetically engineered.( 10 ) Nevertheless, such immunotherapeutic approaches were hampered in osteosarcoma by a lack of defined antigens until we recently identified papillomavirus binding factor (PBF) using an osteosarcoma cell line and an autologous CTL clone restricted by human leukocyte antigen (HLA)‐B*5502.( 11 , 12 ) PBF is a DNA‐binding transcription factor with unknown function.( 13 , 14 ) The oncogenic role of PBF in osteosarcoma and its immunogenicity in patients with common HLA alleles such as HLA‐A2 and HLA‐A24 needs to be disclosed before development of clinically applicable PBF‐based immunotherapy.

In the present study, we analyzed the distribution profile, prognostic impact, and immunogenicity of PBF in patients with osteosarcoma. Immunogenicity analysis focused on frequency and cytotoxicity of T cells in patients with HLA‐A24 allele by using limiting dilution (LD)/mixed lymphocyte peptide culture (MLPC)/tetramer assays.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved under institutional guidelines for the use of human subjects in research. The patients and their families as well as healthy donors gave informed consent for the use of blood samples and tissue specimens in our research.

Generation of anti‐PBF antibody. A polyclonal antibody against PBF was generated by immunizing rabbits with 100 µg of a 15‐mer peptide, CGDTVDSDQFKREED, once per week for six weeks (SigmaGenosys, Sapporo, Japan). The serum was collected seven days after the last immunization and purified using Protein A column. The specificity of the anti‐PBF antibody was confirmed previously by Western blotting and immunostaining.( 12 )

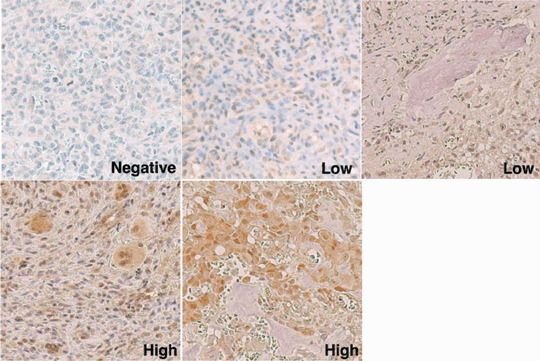

Immunohistochemistry. Formalin‐fixed paraffin‐embedded sections were obtained from 83 biopsy specimens of the primary lesion of osteosarcoma (Table 1). The sections were deparaffinized, boiled in a microwave oven, and blocked with 1% non‐fat dry milk before staining with streptavidin‐biotin‐complex (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan) as previously described.( 15 ) Hematoxylin was used for counter staining. The reactivity of the anti‐PBF antibody was determined by staining of the nuclei of tumor cells.( 12 ) The expression status of PBF was graded semiquantitatively according to the modified classification described by Al‐Batran et al.( 16 , 17 ) negative (positive cells <5%), low (≤5% positive cells ≤50%), and high (positive cells >50%) (Fig. 1). Diffuse expression and heterogeneous expression were regarded as high grade and low grade, respectively. Focal expression was graded as low or negative according to the percentage of positive cells.

Table 1.

The grade of PBF expressioni and the progonosis in 83 patients with osteosarcoma

| Patients | Age | Gender | Location | Surgical stage | Histological type | Chemotherapy | Histological response grade | Operation | PBF expression | EFS (months) | OS (months) | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15 | M | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | T‐12 | 2 | Amputation | High | 39 | 46 | DOD |

| 2 | 20 | M | Humerus | IIB | Osteoblastic | T‐12 | 0 | Amputation | Low | 12 | 24 | DOD |

| 3 | 9 | F | Femur | IIB | Chondroblastic | T‐12 | 0 | WE+FVFG | High | 14 | 22 | DOD |

| 4 | 12 | M | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | T‐12 | 0 | Amputation | Low | 3 | 9 | DOD |

| 5 | 10 | F | Humerus | IIB | Teleangiectatic | T‐12 | 1 | WE+FVFG | High | 103 | 103 | CDF |

| 6 | 17 | F | Humerus | IIB | Osteoblastic | T‐12 | 2 | WE+FVFG | Low | 97 | 97 | CDF |

| 7 | 14 | F | Femur | IIB | Fibroblastic | NSH‐7 | 2 | WE+FVFG | Negative | 119 | 119 | CDF |

| 8 | 14 | M | Fibula | IIB | Chondroblastic | NSH‐7 | 2 | WE | High | 34 | 102 | NED |

| 9 | 11 | F | Tibia | IIB | Osteoblastic | NSH‐7 | 2 | WE+FVFG | Negative | 117 | 117 | CDF |

| 10 | 42 | F | Tibia | IIB | Osteoblastic | NSH‐7 | 2 | WE+Prosthesis | High | 72 | 72 | CDF |

| 11 | 14 | M | Tibia | IIB | Osteoblastic | NSH‐7 | 3 | WE+FVFG | High | 32 | 96 | NED |

| 12 | 18 | M | 2nd rib | IIB | Osteoblastic | NSH‐7 | 0 | WE | High | 106 | 106 | CDF |

| 13 | 33 | M | Pelvis | IIB | Chondroblastic | NECO93J | 1 | WE+FVFG | High | 8 | 13 | DOD |

| 14 | 20 | M | Femur | IIB | Fibroblastic | NECO93J | 2 | WE+FVFG | High | 72 | 72 | CDF |

| 15 | 15 | M | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO93J | 2 | WE+FVFG | High | 106 | 106 | CDF |

| 16 | 15 | M | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO93J | 2 | WE+FVFG | High | 20 | 33 | DOD |

| 17 | 20 | F | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | Not done† | (–)† | Not done† | Negative | 0 | 7 | DOD |

| 18 | 16 | M | Tibia | IIB | Chondroblastic | NECO93J | 2 | WE+FVFG | High | 6 | 6 | DOC‡ |

| 19 | 14 | F | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO93J | 2 | WE | Negative | 5 | 5 | DOC‡ |

| 20 | 15 | M | Fibula | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO93J | 0 | Amputation | High | 13 | 74 | DOD |

| 21 | 13 | M | Humerus | IIB | Chondroblastic | NECO93J | 0 | Amputation | High | 7 | 9 | DOD |

| 22 | 7 | F | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 1 | WE+FVFG | High | 85 | 85 | CDF |

| 23 | 10 | F | Tibia | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 2 | Amputation | Negative | 72 | 72 | CDF |

| 24 | 13 | M | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 0 | WE+RP | Low | 6 | 11 | DOD |

| 25 | 27 | M | Tibia | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 0 | WE+FVFG | High | 8 | 18 | DOD |

| 26 | 18 | F | Femur | IIIB | Fibroblastic | NECO95J | 1 | WE+Prosthesis | High | 0 | 16 | DOD |

| 27 | 20 | F | Humerus | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 2 | WE+Prosthesis | Negative | 67 | 67 | CDF |

| 28 | 69 | F | Femur | IIB | Fibroblastic | NECO95J | 0 | WE+Prosthesis | Low | 62 | 63 | NED |

| 29 | 15 | F | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 3 | WE+FVFG | High | 32 | 32 | CDF |

| 30 | 46 | M | Pelvis | IIB | Fibroblastic | NECO95J | 0 | WE+Fillet | Low | 47 | 60 | NED |

| 31 | 40 | F | Femur | IIB | Fibroblastic | NECO95J | 2 | Amputation | Low | 12 | 20 | DOD |

| 32 | 19 | M | Tibia | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 2 | Amputation | High | 41 | 43 | DOD |

| 33 | 15 | F | Femur | IIB | Fibroblastic | NECO95J | 3 | WE+FVFG | High | 52 | 52 | CDF |

| 34 | 48 | M | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 2 | Amputation | High | 17 | 37 | DOD |

| 35 | 15 | F | Femur | IIIB | Chondroblastic | NECO95J | 1 | WE+FVFG | High | 0 | 17 | NED |

| 36 | 42 | F | Sacrum | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | (–)§ | Not done§ | High | 0 | 18 | NED |

| 37 | 7 | M | Tibia | IIB | Osteoblastic | CCCH2 | 1 | WE+RP | Low | 13 | 86 | DOD |

| 38 | 12 | F | Femur | IIB | Chondroblastic | CCCH2 | 0 | Amputation | Low | 5 | 84 | DOD |

| 39 | 17 | M | Tibia | IIB | Chondroblastic | CCCH2 | 1 | WE+RP | High | 180 | 180 | CDF |

| 40 | 14 | F | Femur | IIB | Fibroblastic | CCCH2 | 0 | WE+Prosthesis | High | 13 | 167 | NED |

| 41 | 19 | M | Tibia | IIB | Fibroblastic | CCCH2 | 0 | WE+RP | Low | 20 | 36 | DOD |

| 42 | 14 | F | Tibia | IIB | Osteoblastic | CCCH2 | 0 | WE+Prosthesis | Low | 19 | 44 | DOD |

| 43 | 12 | M | Tibia | IIB | Osteoblastic | CCCH2 | 2 | WE+Prosthesis | High | 167 | 167 | CDF |

| 44 | 22 | M | Femur | IIB | Fibroblastic | NECO93J | 3 | WE+RP | Low | 164 | 164 | CDF |

| 45 | 21 | M | Femur | IIB | Chondroblastic | NECO93J | 1 | WE+RP | High | 34 | 80 | DOD |

| 46 | 20 | M | Tibia | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO93J | 1 | WE+RP | High | 37 | 131 | NED |

| 47 | 17 | M | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO93J | 3 | WE+FVFG | High | 127 | 127 | CDF |

| 48 | 8 | F | Humerus | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO93J | 3 | WE+FVFG | Low | 126 | 126 | CDF |

| 49 | 20 | F | Humerus | IIB | Fibroblastic | NECO93J | 1 | WE+FVFG | High | 126 | 126 | CDF |

| 50 | 16 | F | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO93J | 2 | WE+RP | High | 124 | 124 | CDF |

| 51 | 18 | M | Tibia | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO93J | 0 | WE+RP | Low | 10 | 15 | DOD |

| 52 | 13 | F | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 1 | WE+Prosthesis | Low | 100 | 100 | CDF |

| 53 | 11 | M | Tibia | IIB | Chondroblastic | NECO93J | 2 | WE+RP | High | 121 | 121 | CDF |

| 54 | 12 | F | Tibia | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 1 | WE+Prosthesis | High | 114 | 114 | CDF |

| 55 | 24 | M | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 1 | WE+Prosthesis | Negative | 79 | 79 | CDF |

| 56 | 14 | F | Humerus | IIB | Chondroblastic | NECO95J | 1 | WE+FVFG | High | 29 | 96 | NED |

| 57 | 26 | M | Tibia | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 0 | WE+Prosthesis | High | 89 | 89 | CDF |

| 58 | 17 | M | Radius | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 1 | WE+FVFG | Low | 84 | 84 | CDF |

| 59 | 18 | F | Femur | IIB | Chondroblastic | NECO95J | 1 | WE+Prosthesis | High | 17 | 69 | DOD |

| 60 | 15 | M | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 2 | WE+Prosthesis | Low | 75 | 75 | CDF |

| 61 | 17 | M | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 2 | WE+Prosthesis | Low | 74 | 74 | CDF |

| 62 | 13 | M | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 2 | WE+Prosthesis | Low | 72 | 72 | CDF |

| 63 | 11 | F | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 3 | WE+Prosthesis | Low | 66 | 66 | CDF |

| 64 | 13 | M | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 2 | WE+Prosthesis | High | 65 | 65 | CDF |

| 65 | 13 | M | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 2 | WE+Prosthesis | Negative | 57 | 57 | CDF |

| 66 | 19 | F | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 1 | WE+Prosthesis | High | 54 | 54 | CDF |

| 67 | 24 | M | Tibia | IIB | Fibroblastic | NECO95J | 0 | WE+Prosthesis | Low | 45 | 45 | CDF |

| 68 | 14 | F | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 2 | WE+Prosthesis | High | 48 | 48 | CDF |

| 69 | 15 | F | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 1 | WE+Prosthesis | Low | 7 | 18 | DOD |

| 70 | 19 | M | Radius | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 1 | WE+FVFG | Low | 27 | 35 | NED |

| 71 | 16 | F | Fibula | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 2 | WE+Prosthesis | Low | 33 | 33 | CDF |

| 72 | 10 | M | Tibia | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 2 | Amputation | High | 12 | 32 | AWD |

| 73 | 11 | M | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 1 | WE+FVFG | Low | 31 | 31 | CDF |

| 74 | 29 | F | Fibula | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 1 | WE | High | 25 | 25 | CDF |

| 75 | 10 | M | Femur | IIB | Chondroblastic | NECO95J | 0 | WE+Prosthesis | High | 9 | 20 | DOD |

| 76 | 8 | M | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 1 | WE+RP | High | 6 | 19 | AWD |

| 77 | 20 | F | Tibia | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 2 | Amputation | High | 16 | 16 | CDF |

| 78 | 12 | M | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 3 | WE+Prosthesis | Low | 15 | 15 | CDF |

| 79 | 65 | M | Tibia | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J¶ | (–)§ | WE+Prosthesis | High | 2 | 13 | NED |

| 80 | 20 | M | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 2 | WE+Prosthesis | High | 12 | 12 | CDF |

| 81 | 16 | M | Ilium | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 1 | WE | High | 13 | 13 | CDF |

| 82 | 12 | M | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 2 | Amputation | High | 8 | 13 | DOD |

| 83 | 20 | M | Femur | IIB | Osteoblastic | NECO95J | 2 | WE+Prosthesis | High | 12 | 12 | CDF |

Chemotherapy and operation were refused by the patient and her family.

‡Died of acute hepatitis B during postoperative chemotherapy.

§Carbon ion radiotherapy was chosen instead of operation.

¶Chemotherapy was instituted only postoperatively. AWD, alive with disease; CDF, continuously disease free; DOC, death of other cause; DOD, death of disease; EFS, event‐free survival; F, female, FVFG, free vascularized fibula graft; M, male; NED, no evidence of disease; OS, overall survival; RP, rotational plasty; PBF, papillomavirus binding factor; WE, wide excision.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical grading of tumor specimens. Representative sections of osteosarcoma specimens stained with an anti‐papillomavirus binding factor antibody are shown (original magnification ×200). Negative indicates that less than 5% of tumor cells were stained positively. Low indicates a positive tumor cell number from 5% to 50%. High indicates a positive tumor cell number of over 50%.

Survivorship analysis. Survivorship analysis was performed for 78 patients with osteosarcoma who had completed the protocols consisting of pre‐ and postoperative chemotherapy and underwent resection of the primary tumor with wide margin or amputation (Table 1). Five patients excluded were due to refusal (Patient 17) or incompletion of the chemotherapy (Patients 18, 19, and 79) and choice of non‐surgical treatment (Patient 36). There were 43 males and 35 females with an average age of 17.9 years. Primary tumors were located in the femur (41 patients), tibia (19 patients), humerus (8 patients), fibula (4 patients), pelvis (3 patients), radius (2 patients) and rib (1 patient). According to Enneking's surgical staging system,( 18 ) 76 patients were stage IIB and 2 patients were stage IIIB. There were 53 osteoblastic, 12 chondroblastic, 12 fibroblastic and 1 teleangiectatic osteosarcomas. Adjuvant chemotherapy protocols comprised of high‐dose methotrexate‐based multidrug regimen, including T‐12,( 19 ) NSH‐7,( 20 ) CCCH2,( 21 ) NECO93J,( 22 ) and NECO95J.( 23 , 24 ) The responses of the tumors to preoperative chemotherapy were histologically graded according to the classification of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association:( 25 ) Grade 0 (tumor necrosis <50%), 1 (≤50% tumor necrosis <90%), 2 (tumor necrosis ≥90%), 3 (No viable tumor cells in the histological sections). These 78 patients were followed up for an average of 65.0 months (range from 9 to 180 months).

The prognostic significance of the following variables overall and in the event‐free survival of patients with osteosarcoma was determined by univariate analysis using the generalized Wilcoxon test: age ( 15), gender (male or female), stage (IIB or IIIB), histological type (osteoblastic, chondroblastic or fibroblastic), response to chemotherapy (Grades 0 and 1 or Grades 2 and 3), and PBF expression status (negative, low or high). The relationship between each variable and PBF expression status was determined by the chi‐squared test. A probability of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Cell lines. An osteosarcoma cell line, OS2000, and an Epstein−Barr virus‐transformed B cell line, LCL‐OS2000, were established previously from a 17‐year‐old patient.( 11 ) Osteosarcoma cell lines HOS and U2OS, and the erythroleukemia cell line K562 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). OS2000, HOS, U2OS and K562 were PBF+ and LCL‐OS2000 was PBF−.( 12 ) The HLA genotypes of osteosarcoma cell lines were as follows: OS2000, A*2402, B*5502, B*4002, Cw*0102; HOS, A*0211, B*5201, Cw*1202; U2OS, A*0201, A*3201, B*4402, Cw*0501, Cw*0704.

Design and synthesis of PBF‐derived peptides. Based on the entire amino acid sequence of PBF, peptides with the ability to bind to HLA‐A24 class I molecules were searched through the Internet site, Bioinformatics and Molecular Analysis Section (BIMAS) HLA Peptide Binding Predictions (http://bimas.cit.nih.gov/).( 26 ) Based on the binding scores, 10 peptides were selected and synthesized (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sequences and binding affinities of PBF‐derived peptides with HLA‐A*2402 binding motif

| Peptide | Position | Sequence | Binding score† | HLA‐peptide binding affinity‡ (% MFI increase ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A24.1 | 84–93 | WYGGQECTGL | 200 | –3.0 ± 3.2 |

| A24.2 | 145–153 | AYRPVSRNI | 84 | 119.2 ± 7.3 |

| A24.3 | 409–418 | AYQALPSFQI | 75 | 25.3 ± 6.0 |

| A24.4 | 254–263 | GFETDPDPFL | 30 | 2.6 ± 10.3 |

| A24.5 | 320–328 | DFYYTEVQL | 20 | 2.3 ± 9.6 |

| A24.6 | 118–127 | RVEEVWLAEL | 15.8 | 22.5 ± 9.6 |

| A24.7 | 254–262 | GFETDPDPF | 15 | –1.2 ± 5.9 |

| A24.8 | 12–20 | RSLLGARVL | 12 | 14.2 ± 5.8 |

| A24.9 | 415–424 | SFQIPVSPHI | 10.5 | 11.7 ± 7.9 |

| A24.10 | 104–113 | VTVWlLEQKL | 9.5 | 7.1 ± 1.2 |

| HIV | RYLRDQQLLGI | 41.2 ± 9.3 |

Binding score was determined by BIMAS HLA Peptide Binding Predictions.

‡The affinity of each peptide was evaluated by a HLA class I stabilization assay. BIMAS, bioinformatics and molecular analysis section; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; PBF, papillomavirus binding factor; SD, standard deviation.

HLA class I stabilization assay. The affinity of peptides for HLA‐A24 molecules was evaluated by cell surface HLA class‐I stabilization assay as described previously.( 27 , 28 ) An HLA‐A*2401‐binding HIV peptide (RYLRDQQLLGI) was used for positive control. Assays were performed in triplicate. The affinity of each peptide for HLA‐A*2402 molecules was evaluated by the percent mean fluorescence intensity (%MFI) increase of the HLA‐A*2402 molecules in the calculation: %MFI increase: [(MFI with the given peptide – MFI without peptide)/(MFI without peptide)] × 100.

Limiting dilution/mixed lymphocyte peptide culture. Prior to frequency analysis and cytotoxicity assays, peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) of patients were subjected to mixed lymphocyte peptide culture under limiting dilution conditions (LD/MLPC) according to the method described by Karanikas et al.( 29 ) with some modifications. For frequency analysis, peripheral blood samples (20 mL) were collected from nine patients with PBF+ osteosarcoma (Patient 26, 36, 76, 78–83) (Table 1). PBMC were suspended in AIM‐V (Invitrogen Crop., Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 1% human serum (HS) and incubated for 60 min at room temperature with PBF A24.2 peptide (25 µg/mL). Peptide‐pulsed PBMC were seeded at 2 × 105 cells/200 µL/well into round‐bottom 96‐microwell plates in AIM‐V with 10%HS, IL‐2 (20 U/mL; a kind gift from Takeda Chemical Industries Ltd, Osaka, Japan) and IL‐7 (10 ng/mL; R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), and incubated. On day 7, half of the medium was replaced by fresh AIM‐V containing IL‐2, IL‐7 and the same peptides. The cell cultures were maintained by adding fresh AIM‐V containing IL‐2. On days 14–21, they were subjected to tetramer‐based frequency analysis.

For cytotoxicity assays, PBMC of Patient 36 were separated into CD8+ cells and CD8− cells using magnetic anti‐CD8 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Gladbach, Germany). CD8− cells were pulsed with the PBF A24.2 peptide for 60 min. Half of the CD8− cells were cryopreserved at –80°C for the second stimulation. CD8+ cells (2.5 × 105/well) and irradiated PBF A24.2 peptide‐pulsed CD8− cells (5 × 105/well) were cocultured in 37 wells of a 48‐well cell culture plate in 500 µL of AIM‐V with 10%HS, IL‐2 and IL‐7. On day 7, the second stimulation was performed by adding irradiated peptide‐pulsed CD8− cells to each culture well in 500 µL of freshly replaced AIM‐V with 10%HS, IL‐2 and IL‐7. On day 14–28, they were subjected to tetramer‐based cytotoxicity assays.

Tetramer‐based frequency analysis. An fluorescein isothiocyanate‐conjugated HLA‐A24/HIV tetramer (here termed the control tetramer) and a phycoerythrin (PE)‐conjugated HLA‐A24/PBF A24.2 tetramer (A24/PBF A24.2 tetramer) were constructed by Medical & Biological Laboratories Co. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). PBMC from patients were stimulated with the PBF A24.2 peptide by LD/MLPC as described above. From each microwell containing 200 µL of the microculture pool, 100 µL was transferred to a V‐bottom microwell and washed. On the spin‐down pellets, the control tetramer and A24/PBF A24.2 tetramer (10 nM in 25 µL of phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS)) were added in combination and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Then a PE‐Cy5‐conjugated anti‐CD8 antibody (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) was added (dilution of 1:30 in 25 µL of PBS containing the control tetramer and A24/PBF A24.2 tetramer) and incubated for another 15 min. The cells were washed in PBS twice, fixed with 0.5% formaldehyde, and analyzed by flow cytometry using FACScan and CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA). CD8+ living cells were gated and the cells labeled with the A24/PBF A24.2 tetramer and non‐labeled cells with the control tetramer were referred to as tetramer‐positive cells. The frequency of anti‐PBF A24.2 CTLs was evaluated using the following calculation: (number of tetramer‐positive wells)/([numbers of total tested wells] × [number of CD8+ cells per well]).

Tetramer‐based cytotoxicity assay. CTL‐mediated cytolytic activity was measured by a 6 h‐51Cr release assay.( 30 ) Osteosarcoma cell lines (OS2000, HOS and U2OS), EB‐transformed B cell line LCL‐OS2000 and K562 were used as the target cells. OS2000 was treated with and without 100 U/mL interferon‐gamma (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) for 48 h. LCL‐OS2000 was also treated with and without peptides (25 µg/mL) for 2 h at room temperature before assay. Target cells were labeled with 100 µCi of 51Cr for 1 h at 37°C. The labeled target cells were suspended in Dulbecco's modified eagle's medium containing 10% fetal calf serum and seeded to microwells (2 × 103 cells/well). Patient 36‐derived CD8+ CTL lines stimulated with the PBF A24.2 peptide by LD/MLPC were used as the effector cells. Tetramer‐positive CTL lines were transferred to V‐bottom microwells, suspended in AIM‐V and mixed with the labeled target cells. In cold‐target inhibition assays, a 100‐fold excess of unlabeled PBF A24.2‐pulsed target cells was added as cold target cells. After a 6 h incubation period at 37°C, the release of the 51Cr level in the supernatant of the culture was measured by quantification in an automated gamma counter. The percentage of specific cytotoxicity was calculated as the percentage of specific 51Cr release: 100 × (experimental release – spontaneous release)/(maximum release – spontaneous release). The cytotoxicity rate to OS2000 was calculated as (%cytotoxicity to each target cells)/(%cytotoxicity to OS2000).

Results

Expression of PBF protein in osteosarcoma. To determine the prevalence of the osteosarcoma‐derived antigen PBF protein in osteosarcomas, we stained formalin‐fixed paraffin‐embedded sections of 83 specimens with a polyclonal antibody against PBF (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Of these, 76 specimens (92%) were positively stained with the anti‐PBF antibody, including 49 specimens (59%) with high‐grade staining.

Prognostic impact of PBF expression in patients with osteosarcoma. We then analyzed the prognostic significance of several variables including expression of PBF, in 78 patients with osteosarcoma who completed chemotherapy protocols and had wide tumor excision (Table 1). As depicted in Table 3, patients with chondroblastic type osteosarcoma showed significantly poorer event‐free survival rate than those with other histological types. Forty‐one patients with osteosarcoma showing a poor response to preoperative chemotherapy (Grades 0 and 1) showed significantly more unfavorable event‐free and overall survival rates than 37 good responders (Grades 2 and 3). With respect to PBF‐expression status, 72 patients with positive expression of PBF in the primary tumor were significantly more unfavorable in event‐free survival than six patients with PBF‐negative osteosarcoma (P = 0.025). This finding was consistent in subgroup analysis with 46 patients with high‐grade PBF expression and 26 patients with low‐grade PBF expression (P = 0.026 and 0.032, respectively). In contrast, age and gender failed to have significant prognostic impacts on event‐free and overall survival rates of the patients.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of variables in event‐free survial and overall survival

| Variables | n | Event‐free survival (months in average) | P‐value | Overall survival (months in average) | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ≤15 | 41 | 49.6 | 0.215 | 66.8 | 0.949 |

| >15 | 37 | 54.7 | 63 | |||

| Gender | Male | 46 | 48.5 | 0.244 | 64.4 | 0.101 |

| Female | 32 | 57.1 | 70.8 | |||

| Stage | IIB | 76 | 53.4 | 0.006 | 66.3 | 0.062 |

| IIIB | 2 | 0 | 16.5 | |||

| Histological type | Osteoblastic | 53 | 52.1 | 0.052* | 60.7 | 0.461* |

| Chondroblastic | 12 | 38.2 | <0.001* | 67.7 | 0.105* | |

| Fibroblastic | 12 | 61.0 | 0.899* | 78.3 | 0.665* | |

| Teleangiectatic | 1 | 103.4 | ||||

| Response to chemotherapy | Grades 0,1 | 41 | 40.5 | <0.001 | 60.2 | 0.007 |

| Grades 2,3 | 37 | 64.7 | 70.3 | |||

| PBF status | Positive | 72 | 49.2 | 0.025 | 63.3 | 0.091 |

| Negative | 6 | 85.2 | 85.2 |

P‐value was determined in comparison with the survival of patients with other subtypes.

Subsequently, we analyzed the relationship between the PBF‐expression status in osteosarcoma and other variables. PBF‐expression status was not significantly related to any variables including age (P = 0.472), gender (P = 0.184), stage (P = 0.694), histological type (P = 0.743) and the response to chemotherapy (P = 0.069).

Affinity of PBF‐derived synthetic peptides to HLA‐A*2402 molecules. To determine the immunogenicity of PBF in patients with HLA‐A24, we synthesized 10 peptides from the PBF sequence in accordance with the BIMAS score for HLA‐A24 affinity (Table 2). Subsequently, we evaluated the affinities of these peptides to HLA‐A24 molecules by the HLA class‐I stabilization assay. As shown in Table 2, peptide PBF A24.2 showed the highest MFI increases in the context of HLA‐A24.

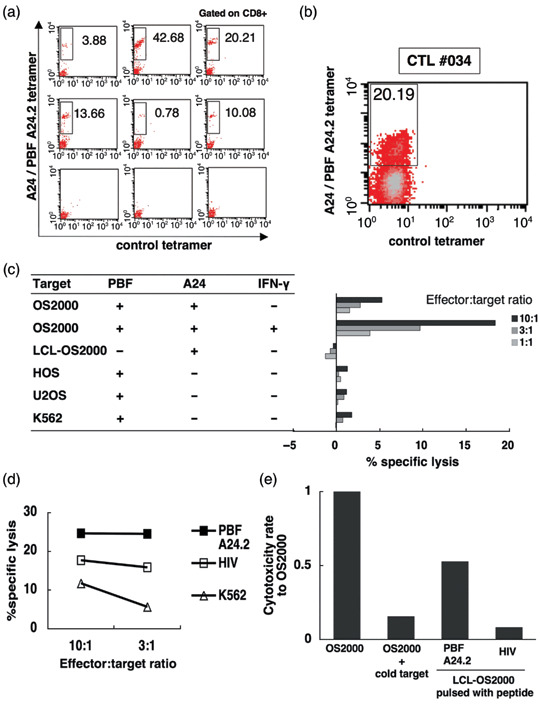

Frequency of anti‐PBF A24.2 CTLs in HLA‐A24+ patients with osteosarcoma. We then examined the frequency of peripheral CD8+ T‐lymphocytes that recognized the PBF A24.2 peptide in 9 HLA‐A24+ patients with PBF+ osteosarcoma by LD/MLPC/tetramer analysis. As depicted in Table 4 and representatively shown in Fig. 2(a), anti‐PBF A24.2 CTLs were detected as tetramer‐positive cells in eight of the nine patients with osteosarcoma. The frequencies of anti‐PBF A24.2 CTLs were between 5 × 10−7 and 7 × 10−6 (4 × 10−6 in average) in eight tetramer‐positive patients.

Table 4.

Clinical picture and frequency of anti‐PBF A24.2 peptide CTLs in PBMC of patients with PBF‐positive osteosacoma

| Participants | Status of tumor bearing | Chemotherapy | Total number of tested wells | Number of tetramer‐ positive wells | Number of PMBC | %CD8 | Number of CD8+ cells per pool | Frequency † |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | ||||||||

| 26 | (P)‡, M | underway | 62 | 14 | 200 000 | 17 | 34 000 | 7 × 10−6 |

| 36 | P | not done | 194 | 6 | 210 000 | 23 | 48 000 | 6 × 10−7 |

| 76 | (P) | underway | 19 | 2 | 200 000 | 9 | 18 000 | 6 × 10−6 |

| 78 | (P) | underway | 62 | 1 | 200 000 | 15 | 30 000 | 5 × 10−7 |

| 79 | (P), M | underway | 28 | 0 | 200 000 | 15 | 30 000 | <1 × 10−6 |

| 80 | (P) | underway | 160 | 15 | 290 000 | 20 | 58 000 | 2 × 10−6 |

| 81 | (P) | underway | 149 | 5 | 200 000 | 3 | 6000 | 6 × 10−6 |

| 82 | (P) | underway | 132 | 3 | 200 000 | 4 | 8000 | 3 × 10−6 |

| 83 | P | underway | 40 | 5 | 200 000 | 25 | 50 000 | 3 × 10−6 |

Frequency of anti‐PBF A24.2 CTLs among CD8+ cells.

‡Parentheses indicate that the tumor had been present previously but was free at the time blood sample was taken. CTLs, cytotoxic T lymphocytes; M, metastatic tumor; P, primary tumor; PBF, papillomavirus binding factor; PMBC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

Figure 2.

Tetramer‐based detection of anti‐PBF A24.2 peptide CTLs in peripheral blood of patients with osteosarcoma. (a) peripheral blood mononuclear cell of Patient 26 were seeded into 62 microwells and stimulated with the papillomavirus binding factor (PBF) A24.2 peptide by mixed lymphocyte peptide culture under limiting dilution conditions (LD/MLPC). The resultant cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) pools were stained with the phycoerythrin (PE)‐conjugated A24/PBF A24.2 tetramer, fluorescein isothiocyanate‐conjugated control tetramer, and a PE‐Cy5‐conjugated anti‐CD8 mAb. Cells reacting with the anti‐CD8 mAb were gated. The reactivity of gated cells with the A24/PBF A24.2 tetramer and the control tetramer are shown. The upper and middle columns display six representative pools with positive reactivity to the A24/PBF A24.2 tetramer. The cells labeled with the A24/PBF A24.2 tetramer and non‐labeled cells with the control tetramer were considered to be tetramer‐positive cells and are boxed to show their proportion among CD8+ cells. The bottom row shows three negative pools. (b) CD8+ cells (2.5 × 105 cells/well) of Patient 36 were seeded into 37 wells of a 48‐well culture plate and stimulated with irradiated peptide‐pulsed CD8− cells (5 × 105 cells/well) by LD/MLPC. Tetramer analysis was performed on day 14. The results of one of the four tetramer‐positive CTL line (CTL #034) in the 37 pools are shown. Cells reacting with the anti‐CD8 mAb were gated. The tetramer‐positive cells are boxed to show their proportion among CD8+ cells. (c) The cytotoxicity of CTL #034 against allogeneic osteosarcoma cell lines (OS2000, HOS, U2OS), LCL‐OS2000 and K562 was assessed by a 6 h standard 51Cr release assay at the indicated effector:target ratios. OS2000 was assayed in the presence and absence of 48 h‐interferon‐gamma pretreatment. (d) The cytotoxicity of CTL #034 against peptide‐pulsed LCL‐OS2000 and K562 was assessed by a 6 h standard 51Cr release assay at the indicated effector:target ratios. LCL‐OS2000 was pulsed with 25 µg/mL of PBF A24.2 peptide or HIV control peptide for 2 h at room temperature before labeling with 51Cr. (e) Cold target inhibition assay. The cytotoxicity of CTL #034 against interferon‐gamma‐treated, 51Cr‐labeled OS2000 was assessed in the presence and absence of a 100‐fold excess of PBF A24.2 peptide‐pulsed, cold LCL‐OS2000 at a 10:1 effector‐target ratio. 51Cr‐labeled LCL‐OS2000 cells pulsed with the PBF A24.2 peptide or HIV peptide were also used as control target cells.

Tetramer‐based cytotoxicity of anti‐PBF A24.2 CTLs against osteosarcoma cell lines. Finally we assessed the cytotoxic activity of tetramer‐positive cells against allogeneic osteosarcoma cell lines. We induced tetramer‐positive anti‐PBF A24.2 CTLs from 1 × 107 CD8+ cells of Patient 36 by LD/MLPC using 48‐well culture plates. Irradiated peptide‐pulsed CD8− cells were used as stimulator cells. As a result, 4 of 37 tetramer‐positive CTLs were detected by tetramer analysis on day 14. Four tetramer‐positive CTLs contained 3.47%, 0.03%, 15.26% and 20.19%. One of four CTL lines (CTL #034) was shown in Fig. 2(b).

The cytotoxicity against OS2000 (PBF+, A24+), LCL‐OS2000 (PBF−, A24+), HOS (PBF+, A24−), U2OS (PBF+, A24−) and K562 (PBF+, HLA class I loss) was comparatively assessed by 51Cr release assay. As depicted in Fig. 2(c), CTL #034 showed specific cytotoxicity against OS2000 and the cytotoxicity was enhanced by interferon‐gamma pretreatment. In contrast, none of these CTL lines exhibited cytotoxic activity against LCL‐OS2000, HOS, U2OS, or K562 cells. The other three tetramer‐positive CTL lines also showed specific cytotoxicity against OS2000 (data not shown).

We subsequently determined the specificity of cytotoxicity with the PBF A24.2 peptide by using peptide‐pulsed LCL‐OS2000. As shown in Fig. 2(d), CTL #034 lyzed PBF A24.2 peptide‐pulsed LCL‐OS2000 more than control peptide (HIV)‐pulsed LCL‐OS2000 or K562 cells. Peptide‐specific cytotoxicity of CTL #034 was also assessed by cold‐target inhibition assay (Fig. 2e). Cytotoxicity against OS2000 pretreated with interferon‐gamma was inhibited by adding a 100‐fold excess of cold LCL‐OS2000 pulsed with PBF A24.2.

Discussion

In the present study, we examined the distribution profile, prognostic impact, and immunogenicity of the novel tumor‐associated antigen PBF in osteosarcoma. We found: (i) that 92% of 83 osteosarcoma specimens expressed PBF protein; (ii) that PBF‐positive osteosarcomas conferred a significantly poorer prognosis than those with negative expression of PBF in event‐free survival of 78 patients who completed the standard treatment; (iii) that CD8+ T cells reacting with a PBF‐derived HLA‐A24‐binding peptide (PBF A24.2 peptide) were detected in eight out of nine HLA‐A24‐positive patients with osteosarcoma at the frequency from 5 × 10−7 to 7 × 10−6; and (iv) that PBF A24.2 peptide induced CTL lines from an HLA‐A24‐positive patient, which specifically killed an osteosarcoma cell line that expresses both PBF and HLA‐A24. These findings suggest the oncogenic and antigenic role of PBF in patients with osteosarcoma, especially those with HLA‐A24. The proof of immunogenicity of PBF has been limited to an HLA‐B55‐positive patient with osteosarcoma.( 12 ) Wide distribution of PBF in osteosarcoma and the immunogenicity of PBF seen in patients with HLA‐A24 extended the possibility of PBF‐targeted immunotherapy against osteosarcoma. Patients with negative expression of PBF in osteosarcoma can be treated successfully by the current chemotherapy‐based treatment protocols.

To date, peptide‐based immunotherapy in patients with bone and soft tissue sarcomas has been reported only with the use of fusion gene‐derived peptides.( 31 , 32 ) This approach has been available for tumors in which specific chromosomal translocations have been identified, including synovial sarcoma and Ewing sarcoma. However, for other sarcomas including osteosarcoma, where chromosomal translocation and a resultant fusion gene have not been identified, novel tumor‐associated antigens need to be defined. With this aim, we developed autologous pairs of tumor cells and CTLs from patients with sarcomas. Consequently, PBF was identified from an autologous osteosarcoma‐CTL pair. PBF protein was defined in 89% of the various bone and soft tissue sarcomas (Tsukahara et al. 2004, unpub. data). Therefore, the PBF A24.2 peptide might be applicable to immunotherapy against bone and soft tissue sarcomas without known chromosomal translocations, other than osteosarcoma.

Our univariate analysis revealed prognostic significance of PBF in event‐free survival. Such prognostic values need to be verified by multivariate analysis. In this regard, all of the six patients with PBF‐negative osteosarcoma analyzed are continuously disease‐free. Unfortunately, the disproportional profile of these patients caused failure in multivariate analysis. In contrast, poor response to chemotherapy and chondroblastic subtype remained significant in the multivariate analysis (Tsukahara et al. 2007, unpub. data), indicating the validity of the patient population in the present analysis. The unfavorable prognostic value of PBF was also seen in our analysis with 20 patients with Ewing sarcoma.( 33 )

The frequency of anti‐PBF CTL precursor was determined between 5 × 10−7 and 7 × 10−6. In melanoma patients, the anti‐MAGE3.A1 CTL precursor frequency was estimated to be <10−7 in normal donors and prevaccinated patients, and 10−6 in postvaccinated patients.( 34 ) Although the anti‐PBF A24.2 peptide CTL precursor frequency defined in the present study was relatively higher than the anti‐MAGE3.A1 CTL frequency, it was still under the detection level of the standard tetramer analysis and thus required the LD/MLPC/tetramer procedure for detection. The LD/MLPC/tetramer procedure was advantageous with its high sensitivity for the frequency analysis of peptide‐specific CTLs in preclinical studies and clinical trials.( 35 , 36 ) Also, this procedure served as prescreening of CTLs for subsequent cytotoxicity analysis. However, the multistep procedure of LD/MLPC/tetramer analysis requires labor‐intensive laboratory work and long‐term cell culture.( 37 , 38 ) This gives rise to a concern about possible changes in the effector function and differentiation status of CTLs during the analysis.( 39 , 40 )

Cytotoxicity of CTL induced with PBF A24.2 peptide was proved only in an osteosarcoma cell line that is positive for PBF and HLA‐A24. It would be ideal to conduct cytotoxicity assays with more number of cell lines. However, limited cell numbers of CTL lines expanded after LD/MLPC/tetramer analysis made it difficult to carry out. Instead, we examined the specificity of the cytotoxicity by peptide‐pulsation as well as cold inhibition assays.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated the feasibility and population of candidates for PBF‐targeted immunotherapy for osteosarcoma. The combination of LD/MLPC with tetramer labeling as well as 51Cr release cytotoxicity assay enables us to concurrently determine the frequency and function of CTL precursors, and thus serves as a useful tool for identification of novel antigenic peptides and immunomonitoring in clinical immunotherapy trials.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Pierre G. Coulie and Tomoko So for their kind advice about the LD/MLPC/tetramer procedure, Dr Hideo Takasu for the kind donation of synthetic peptides and Drs Naoki Hatakeyama and Takeshi Terui for their clinical support with chemotherapy and donation of blood samples.

Grant support: This work was supported by Grants‐in‐Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (Grant no. 16209013 to N. Sato), Practical Application Research from the Japan Science and Technology Agency (Grant No. H14‐2 to N. Sato), the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (Grant No. H17‐Gann‐Rinsyo‐006 to T. Wada), Postdoctoral Fellowship of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant no. 02568 to T. Tsukahara) and Northern Advancement Center for Science and Technology (Grant No. H18‐Waka‐075 to T. Tsukahara).

References

- 1. Ferrari S, Smeland S, Mercuri M et al . Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with high‐dose ifosfamide, high‐dose methotrexate, cisplatin, and doxorubicin for patients with localized osteosarcoma of the extremity: a joint study by the Italian and Scandinavian Sarcoma Groups. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 8845–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lewis VO. What's new in musculoskeletal oncology. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007; 89: 1399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Campbell CJ, Cohen J, Enneking WF. Editorial: New therapies for osteogenic sarcoma. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1975; 57: 143–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kawaguchi S, Wada T, Tsukahara T et al . A quest for therapeutic antigens in bone and soft tissue sarcoma. J Transl Med 2005; 3: 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Meyers PA, Schwartz CL, Krailo M et al . Osteosarcoma: a randomized, prospective trial of the addition of ifosfamide and/or muramyl tripeptide to cisplatin, doxorubicin, and high‐dose methotrexate. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 2004–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maki RG. Future directions for immunotherapeutic intervention against sarcomas. Curr Opin Oncol 2006; 18: 363–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mocellin S, Mandruzzato S, Bronte V, Lise M, Nitti D, Part I. Vaccines for solid tumours. Lancet Oncol 2004; 5: 681–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Van Baren N, Bonnet MC, Dreno B et al . Tumoral and immunologic response after vaccination of melanoma patients with an ALVAC virus encoding MAGE antigens recognized by T cells. J Clin Oncol 2005; 35: 9008–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thurner B, Haendle I, Roder C et al . Vaccination with MAGE‐3A1 peptide‐pulsed mature, monocyte‐derived dendritic cells expands specific cytotoxic T cells and induces regression of some metastases in advanced stage IV melanoma. J Exp Med 1999; 190: 1669–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR et al . Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes. Science 2006; 314: 126–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nabeta Y, Kawaguchi S, Sahara H et al . Recognition by cellular and humoral autologous immunity in a human osteosarcoma cell line. J Orthop Sci 2003; 8: 554–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tsukahara T, Nabeta Y, Kawaguchi S et al . Identification of human autologous cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte‐defined osteosarcoma gene that encodes a transcriptional regulator, papillomavirus binding factor. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 5442–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boeckle S, Pfister H, Steger G. A new cellular factor recognizes E2 binding sites of papillomaviruses which mediate transcriptional repression by E2. Virology 2002; 293: 103–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sichtig N, Silling S, Steger G. Papillomavirus binding factor (PBF)‐mediated inhibition of cell growth is regulated by 14–3–3 beta. Arch Biochem Biophys 2007; 464: 90–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tsukahara T, Kawaguchi S, Ida K et al . HLA‐restricted specific tumor cytolysis by autologous T‐lymphocytes infiltrating metastatic bone malignant fibrous histiocytoma of lymph node. J Orthop Res 2006; 24: 94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Al‐Batran SE, Rafiyan MR, Atmaca A et al . Intratumoral T‐cell infiltrates and MHC class I expression in patients with stage IV melanoma. Cancer Res 2005; 65: 3937–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tsukahara T, Kawaguchi S, Torigoe T et al . Prognostic significance of HLA class I expression in osteosarcoma defined by anti‐pan HLA class I monoclonal antibody, EMR8‐5. Cancer Sci 2006; 97: 1374–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Enneking WF. A system of staging musculoskeletal neoplasms. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1986; 204: 9–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rosen G, Nirenberg A. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for osteogenic sarcoma: a five year follow‐up (T‐10) and preliminary report of new studies (T‐12). Prog Clin Biol Res 1985; 201: 39–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wada T, Isu K, Takeda N, Usui M, Ishii S, Yamawaki S. A preliminary report of neoadjuvant chemotherapy NSH‐7 study in osteosarcoma: preoperative salvage chemotherapy based on clinical tumor response and the use of granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor. Oncology 1996; 53: 221–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yonemoto T, Tatezaki S, Ishii T, Satoh T, Kimura H, Iwai N. Prognosis of osteosarcoma with pulmonary metastases at initial presentation is not dismal. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1998; 349: 194–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ishii T, Tatezaki S. The results of a cooperative study of chemotherapy for osteosarcoma (NECO 93J). J Jpn Orthop Assoc 1999; 73: S1129. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Isu K, Yamawaki S, Beppu Y et al . Prognostic results from multi‐institute study of adjuvant chemotherapy for osteogenic sarcoma. J Jpn Orthop Assoc 1999; 73: S1135. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kaya M, Wada T, Nagoya S, Kawaguchi S, Isu K, Yamashita T. Concomitant tumour resistance in patients with osteosarcoma. A clue to a new therapeutic strategy. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004; 86: 143–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. The JOA Musculo‐Skeletal Tumor Comittee . General Rules for Clinical and Pathological Studies on Malignant Bone Tumors, 2nd edn. Tokyo: Kanabara, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Parker KC, Bednarek MA, Coligan JE. Scheme for ranking potential HLA‐A2 binding peptides based on independent binding of individual peptide side‐chains. J Immunol 1994; 152: 163–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kuzushima K, Hayashi N, Kimura H, Tsurumi T. Efficient identification of HLA‐A*2402‐restricted cytomegalovirus‐specific CD8 (+) T‐cell epitopes by a computer algorithm and an enzyme‐linked immunospot assay. Blood 2001; 98: 1872–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ida K, Kawaguchi S, Sato Y et al . Crisscross CTL induction by SYT‐SSX junction peptide and its HLA‐A*2402 anchor substitute. J Immunol 2004; 173: 1436–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Karanikas V, Lurquin C, Colau D et al . Monoclonal anti‐MAGE‐3 CTL responses in melanoma patients displaying tumor regression after vaccination with a recombinant canarypox virus. J Immunol 2003; 171: 4898–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sato Y, Nabeta Y, Tsukahara T et al . Detection and induction of CTLs specific for SYT‐SSX‐derived peptides in HLA‐A24(+) patients with synovial sarcoma. J Immunol 2002; 169: 1611–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dagher R, Long LM, Read EJ et al . Pilot trial of tumor‐specific peptide vaccination and continuous infusion interleukin‐2 in patients with recurrent Ewing sarcoma and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma: an inter‐institute NIH study. Med Pediatr Oncol 2002; 38: 158–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kawaguchi S, Wada T, Ida K et al . Phase I vaccination trial of SYT‐SSX junction peptide in patients with disseminated synovial sarcoma. J Transl Med 2005; 3: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yabe H, Tsukahara T, Kawaguchi S et al . Overexpression of papillomavirus binding factor in Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors coferring poor prognosis. Oncol Rep 2007; 19: 129–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lurquin C, Lethe B, De Plaen E et al . Contrasting frequencies of antitumor and anti‐vaccine T cells in metastases of a melanoma patient vaccinated with a MAGE tumor antigen. J Exp Med 2005; 201: 249–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Coulie PG, Karanikas V, Colau D et al . A monoclonal cytolytic T‐lymphocyte response observed in a melanoma patient vaccinated with a tumor‐specific antigenic peptide encoded by gene MAGE‐3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001; 98: 10290–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. So T, Hanagiri T, Chapiro J et al . Lack of tumor recognition by cytolytic T lymphocyte clones recognizing peptide 195–203 encoded by gene MAGE‐A3 and presented by HLA‐A24 molecules. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2007; 56: 259–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Coulie PG, Connerotte T. Human tumor‐specific T lymphocytes: does function matter more than number? Curr Opin Immunol 2005; 17: 320–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Boon T, Coulie PG, Van den Eynde BJ, Van Der Bruggen P. Human T cell responses against melanoma. Annu Rev Immunol 2006; 24: 175–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Speiser DE, Lienard D, Rufer N et al . Rapid and strong human CD8+ T cell responses to vaccination with peptide, IFA, and CpG oligodeoxynucleotide 7909. J Clin Invest 2005; 115: 739–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Romero P, Cerottini JC, Speiser DE. The human T cell response to melanoma antigens. Adv Immunol 2006; 92: 187–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]