Abstract

Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR‐TKIs) inhibit the function of certain adenosine triphosphate (ATP)‐binding cassette transporters, including P‐glycoprotein/ABCB1 and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP)/ABCG2. We previously reported an antagonistic activity of gefitinib towards BCRP. We have now analyzed the effects of erlotinib, another EGFR‐TKI, on P‐glycoprotein and BCRP. As with gefitinib, erlotinib effectively reversed BCRP‐mediated resistance to SN‐38 (7‐ethyl‐10‐hydroxycamptothecin) and mitoxantrone. In contrast, we found that erlotinib effectively suppressed P‐glycoprotein‐mediated resistance to vincristine and paclitaxel, but did not suppress resistance to mitoxantrone and doxorubicin. Conversely, erlotinib appeared to enhance P‐glycoprotein‐mediated resistance to mitoxantrone in K562/MDR cells. This bidirectional activity of erlotinib was not observed with verapamil, a typical P‐glycoprotein inhibitor. Flow cytometric analysis showed that erlotinib co‐treatment restored intracellular accumulation of mitoxantrone in K562 cells expressing BCRP, but not in cells expressing P‐glycoprotein. Consistently, erlotinib did not inhibit mitoxantrone efflux in K562/MDR cells although it did vincristine efflux in K562/MDR cells and mitoxantrone efflux in K562/BCRP cells. Intravesicular transport assay showed that erlotinib inhibited both P‐glycoprotein‐mediated vincristine transport and BCRP‐mediated estrone 3‐sulfate transport. Intriguingly, Lineweaver‐Burk plot suggested that the inhibitory mode of erlotinib was a mixed type for P‐glycoprotein‐mediated vincristine transport whereas it was a competitive type for BCRP‐mediated estrone 3‐sulfate transport. Collectively, these observations indicate that the pharmacological activity of erlotinib on P‐glycoprotein‐mediated drug resistance is dependent upon the transporter substrate. These findings will be useful in understanding the pharmacological interactions of erlotinib used in combinational chemotherapy. (Cancer Sci 2009; 100: 1701–1707)

The ABC transporter protein P‐glycoprotein/ABCB1 consists of two symmetrical halves connected by a linker region, with each half containing an ATP‐binding domain and a six transmembrane domain.( 1 ) P‐glycoprotein has been investigated as a key cancer‐related protein whose overexpression can lead to a tumor cell multidrug resistant phenotype.( 1 ) P‐glycoprotein transports out of cells various structurally unrelated chemotherapeutic agents, including vincristine (VCR), paclitaxel (PTX), doxorubicin (DOX), and mitoxantrone (MXR), thereby reducing their cytotoxic effects.( 1 ) Overexpression of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP)/ABCG2, a half‐type ABC transporter with an ATP‐binding domain and a six transmembrane domain, also modulates the efficacy of cancer chemotherapeutics,( 2 ) rendering cancer cells resistant to various chemotherapeutic drugs. BCRP functions as a homodimer, transporting anticancer agents such as topotecan, irrinotecan, SN‐38 (7‐ethyl‐10‐hydroxycamptothecin), methotrexate, and MXR out of cells.( 3 )

A number of compounds have been tested for their ability to overcome ABC transporter‐mediated drug resistance. Verapamil, cyclosporine A, and others have been identified as inhibitors of P‐glycoprotein,( 1 , 4 , 5 ) while fumitremorgin C (FTC), tamoxifen derivatives, and certain flavonoids inhibit BCRP.( 3 , 6 , 7 , 8 ) These reagents directly interact with P‐glycoprotein or BCRP and competitively interfere with transporter‐substrate binding. This inhibition restores intracellular accumulation of the substrate drugs, effectively reversing drug resistance.

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is a member of the ErbB/HER family of receptor tyrosine kinases and is frequently deregulated in human cancers, including non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), breast cancer, and glioblastomas.( 9 ) As such, abnormal activation of EGFR signaling is a promising therapeutic target. Gefitinib and erlotinib, both EGFR inhibitory 4‐anilinoquinazoline derivatives, are currently utilized in clinical chemotherapy, especially for lung cancer.( 10 ) Extensive examination of functional interactions between BCRP and imatinib or gefitinib revealed that these kinase inhibitors are also substrates for BCRP with potent inhibitory activity against this ABC transporter.( 11 , 12 )

Erlotinib is an orally active EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) with efficacy in NSCLC, ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, head and neck squamous cell cancer, and primary glioblastoma.( 13 ) Erlotinib is approved in the United States for treatment of locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC after failure of at least one prior chemotherapy regimen.( 14 ) It was also recently approved for use in combination with gemcitabine as a first line treatment for patients with locally advanced, unresectable, or metastatic pancreatic cancer.( 15 ) Several clinical studies are planned to examine the combinational effects of erlotinib or gefitinib on conventional chemotherapy with various tumors. Detailed exploration of the pharmacological interaction between erlotinib and anticancer agents will contribute to optimize synergistic effects in such combination chemotherapy. Most recently, Shi et al. reported that erlotinib antagonized both P‐glycoprotein‐ and BCRP‐mediated drug resistances through direct inhibition of their efflux activities.( 16 , 17 ) In the present study, we demonstrate that erlotinib inhibition of P‐glycoprotein activity is substrate‐specific.

Materials and Methods

Reagents. Erlotinib was kindly provided by F. Hoffmann‐La Roche (Basel, Switzerland). SN‐38 was provided by Yakult Honsha (Tokyo, Japan). FTC was purchased from Alexis (San Diego, CA, USA) and verapamil was purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). All other anticancer drugs were commercially available. MTT (3‐[4,5‐dimethyl‐2‐thiazolyl]‐2,5‐diphenyl‐2H‐tetrazolium bromide) was obtained from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, (Osaka, Japan).

Cells and drug sensitivity assay. PC‐9 human NSCLC cells and K562 human myelogenous leukemia cells were cultured in DMEM and RPMI‐1640 mediums, respectively, supplemented with 7% fetal bovine serum and kanamycin (50 µg/mL) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. BCRP‐expressing K562 cells (K562/BCRP), P‐glycoprotein‐expressing K562 cells (K562/MDR), and BCRP‐expressing PC‐9 cells (PC‐9/BCRP) were established previously.( 2 ) PC‐9/MDR cells were established by the transduction of PC‐9 with a HaMDR retrovirus harboring a Myc‐tagged human MDR1 cDNA in the Ha retrovirus vector as described previously.( 18 )

Erlotinib‐induced growth inhibition of PC‐9 and K562 cell lines was determined using a Coulter counter as described previously.( 8 ) The effects of erlotinib on cell sensitivity to anticancer drugs were evaluated by MTT assay. Briefly, cells were seeded at 2 × 103 cells/well in 96‐well plates. After incubation at 37 °C for 5 days in the presence of various concentrations of the drugs, MTT solution was added into each well and incubated for 4 h. An SDS/HCl solution was then added and incubated overnight to dissolve the formazan precipitate. Finally, OD570 was measured to estimate cell growth. IC50 values (the dosage of drug at which a 50% inhibition of cell growth was achieved) were determined from the growth inhibition curve. Reversal indices (RI50) were defined as the concentration of inhibitors (erlotinib, verapamil or FTC) that caused a 2‐fold reduction in the IC50 values for anticancer drugs in each resistant cell as described previously.( 8 )

Intracellular accumulation of mitoxantrone. The effect of erlotinib on the cellular accumulation of MXR was determined by flow cytometry. K562, K562/BCRP, and K562/MDR cells (5 × 105 cells each) were incubated with 300 nmol/L MXR at 37 °C for 40 min in the absence or presence of erlotinib (0.1, 1, and 10 µmol/L), verapamil (1 and 10 µmol/L), or FTC (1 and 10 µmol/L). Cells were then washed with ice‐cold PBS and subjected to fluorescence analysis using a BD LSR II system (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA). MXR fluorescence was measured using a red 633‐nm laser and a 660/20‐band pass filter.

Intravesicular transport assay. Membrane vesicles of K562/MDR cells were prepared according to the method described previously.( 19 ) The vesicular transport assay was done by a rapid centrifugation technique using 3H‐labeled VCR, MXR (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, St. Louis, MO, USA) and estrone 3‐sufate (E1S) (Perkin‐Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA, USA) as essentially described before.( 12 ) In brief, the transport reaction mixture (50 µL volume; 50 mmol/L Tris‐HCl [pH 7.4], 10 mmol/L MgCl2, 250 mmol/L sucrose, 10 mmol/L phosphocreatine, 100 µg/mL creatine phosphokinase, with or without 3 mmol/L ATP, 100 nmol/L [3H]VCR or 50 nmol/L [3H]E1S, and membrane vesicles containing 10 µg protein) was kept on ice for 5 min and then reaction was started by incubation at 25 °C for 10 min. The reaction was terminated by an addition of 1 mL of ice‐cold stop solution (10 mmol/L Tris‐HCl [pH 7.4], 100 mmol/L NaCl, 250 mmol/L sucrose). The membrane vesicles were collected by centrifugation at 18 000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The pellets were solubilized to measure their radioactivity levels by a liquid scintillation counter.

Cellular efflux assay. Cells (106/mL) were incubated with 0.2 µmol/L 3H‐labeled MXR or VCR for 30 min at 37 °C, washed twice with ice‐cold PBS, and then suspended in ice‐cold 3H‐free fresh normal growth medium. Aliquots of them were immediately mixed with ice‐cold growth medium containing inhibitor (10 µmol/L each), stood in ice‐water for 5 min, and then incubated at 37 °C for indicated times. Cell suspensions were centrifuged at 800 g for 5 min, and supernatants were collected to measure [3H] radioactivity levels exported from cells by a liquid scintillation counter.

Results

Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP)‐mediated erlotinib resistance in PC‐9 cells but not in K562 cells. The NSCLC cell line PC‐9 harbors an EGFR gene with a 15‐bp deletion( 20 ) and shows enhanced sensitivity to the EGFR inhibitor gefitinib. K562 cells, on the other hand, express very little EGFR and do not show selective sensitivity to gefitinib inhibition.( 12 ) We have observed that BCRP transports gefitinib and confers resistance to gefitinib only in gefitinib‐sensitive cells such as PC‐9, but not in non‐sensitive cells such as K562.( 2 )

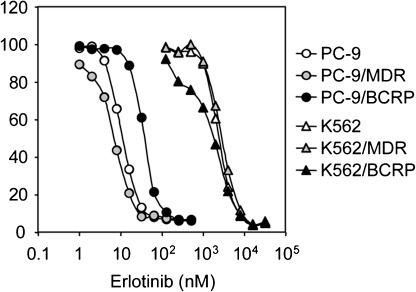

Sensitivity to erlotinib, another EGFR‐TKI, was characterized in PC‐9 and K562 cells expressing P‐glycoprotein or BCRP (PC‐9/MDR, PC‐9/BCRP, K562/MDR, and K562/BCRP). Cells were incubated with erlotinib and the ratio of cell growth inhibition was used to determine IC50 values for each cell line. As shown in Figure 1, erlotinib inhibited PC‐9 cell growth at nanomoler concentrations (IC50, ~10 nmol/L), whereas K562 cells grew normally in the presence of such lower concentrations of erlotinib (IC50, 2.4 µmol/L). Thus, PC‐9 cells were more sensitive to erlotinib than K562 cells. Interestingly, PC‐9/BCRP cells were approximately 2.8‐fold more resistant to erlotinib than parental PC‐9 and PC‐9/MDR cells. The sensitivity of K562/MDR or K562/BCRP cells in erlotinib was almost identical to that of the parental K562 cells. Consistent with the published results for gefitinib,( 12 ) the present findings indicate that BCRP expression confers resistance to erlotinib in PC‐9 cells but not in K562 cells.

Figure 1.

Sensitivity of PC‐9 and K562 cell lines to erlotinib. Cells were cultured for 5 days with increasing concentrations of erlotinib. Cell numbers were determined with a Coulter counter and cell growth inhibition curves (% of control) are shown. Data points are means ± SD calculated from triplicate determinations. Different symbols indicate specific cell lines: PC‐9, open circles; PC‐9/MDR, shaded circles; PC‐9/breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP), filled circles; K562, open triangles; K562/MDR, shaded triangles; and K562/BCRP, filled triangles.

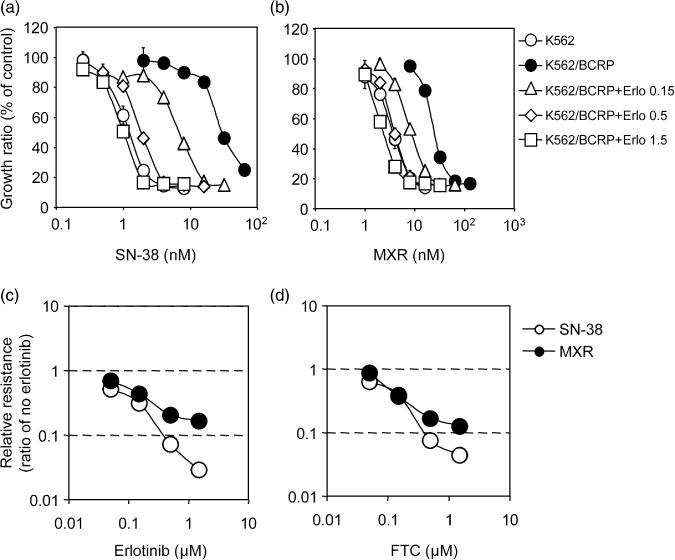

Effects of erlotinib on BCRP‐mediated drug resistance. Gefitinib acts as an inhibitor for transporters and reverses P‐glycoprotein‐ and BCRP‐mediated resistance to various anticancer drugs.( 12 ) K562 cells were not sensitive to the selective cytotoxicity of erlotinib‐mediated EGFR inhibition. Therefore, we used K562/MDR and K562/BCRP cell lines to test such erlotinib reversal activity affecting P‐glycoprotein‐ and BCRP‐mediated drug resistance. K562/BCRP cells showed significant resistance to SN‐38 (~25‐fold) and MXR (~7‐fold). Erlotinib co‐treatment effectively reversed BCRP‐mediated resistance to both drugs (Fig. 2a,b).

Figure 2.

Reversal of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP)‐mediated drug resistance in K562/BCRP cells. The sensitivity of K562/BCRP cells to SN‐38 (7‐ethyl‐10‐hydroxycamptothecin) (a) and mitoxantrone (MXR) (b) was determined in the presence of different concentrations of erlotinib: 0.15 µmol/L, open triangles; 0.5 µmol/L, open diamonds; 1.5 µmol/L, open squares. Cell growth inhibition following 5 days of culture was determined using the MTT assay. Growth inhibition curves were established from the means ± SD of triplicate determinations. Similar experiments were performed in the presence of fumitremorgin C (FTC) and the relative resistance to SN‐38 (open circles) or MXR (filled circles) in the presence erlotinib (c) or FTC (d) was calculated as the ratio of an IC50 value in the presence of an inhibitor divided by the IC50 value without inhibitors.

The dose dependency of this erlotinib‐mediated suppressive effect was also analyzed. Erlotinib at 1.5 µmol/L (Fig. 2, open squares) effectively eliminated BCRP‐mediated resistance to SN‐38 and MXR. In similar experiments using erlotinib or FTC as a control inhibitor of BCRP‐mediated resistance, both drugs reduced resistance to SN‐38 and MXR in a dose‐dependent manner (Fig. 2c,d). BCRP‐mediated drug resistance reversal abilities for erlotinib and FTC were calculated as the RI50 value that caused a 2‐fold reduction in the IC50 for each drug. As shown in Table 1, the RI50 values of erlotinib to SN‐38 and MXR were 0.05 and 0.1 µmol/L, respectively. Interestingly, SN‐38 resistance was more susceptible to erlotinib than MXR resistance. The RI50 values of erlotinib were comparable with those of FTC. Thus, erlotinib and FTC appeared to have equivalent inhibitory activities against BCRP‐mediated drug resistance.

Table 1.

Values of RI50 (µM) to BCRP‐mediated resistance

| Erlotinib | FTC | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| BCRP | MXR | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.02 |

| SN‐38 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.02 |

Means ± SD. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

BCRP, breast cancer resistance protein; FTC, fumitremorgin C; MXR, mitoxantrone; RI50, reversal indices; SN‐38, 7‐ethyl‐10‐hydroxycamptothecin.

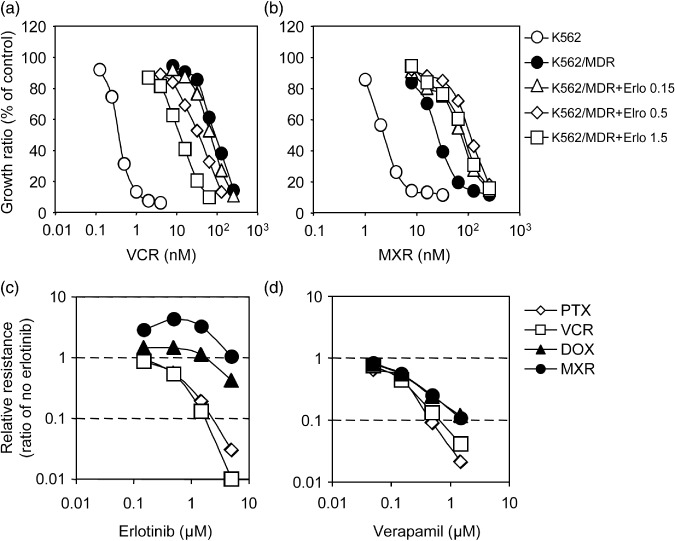

Distinct modulation of P‐glycoprotein‐mediated drug resistance by erlotinib. Although our experiments did not show obvious erlotinib‐resistance in PC‐9/MDR cells, we examined the effects of erlotinib on P‐glycoprotein‐mediated drug resistance in K562 cells based on reports that gefitinib was able to reverse P‐glycoprotein‐mediated drug resistance. MTT assays showed that K562/MDR cells were resistant to VCR (relative resistance was ~360‐fold), PTX (~1000‐fold), DOX (~25‐fold), and MXR (~9‐fold) (data not shown). We next examined the effects of erlotinib at various concentrations. Representative results showing K562/MDR cell resistance to VCR and to MXR are presented in Figure 3(a,b). As previously reported for gefitinib,( 12 ) erlotinib effectively reversed VCR‐resistance in K562/MDR cells (Fig. 3a). However, when K562/MDR cells were co‐treated with erlotinib at 1.5 µmol/L, cells still showed significant resistance to VCR (~32‐fold, open squares), whereas erlotinib completely eliminated BCRP‐mediated resistance to SN‐38 (as shown in Fig. 2a). Higher concentrations of erlotinib (over 5 µmol/L) were required for complete reversal of P‐glycoprotein‐mediated VCR‐resistance. Moreover, we unexpectedly found that in K562/MDR cells, erlotinib did not reverse resistance to MXR. Conversely, erlotinib at concentrations of 0.15–1.5 µmol/L shifted the growth inhibition curve to the right (Fig. 3b), suggesting that erlotinib treatment stimulated P‐glycoprotein‐mediated resistance to MXR.

Figure 3.

Reversal of P‐glycoprotein‐mediated drug resistance in K562/MDR cells. The sensitivity of K562/MDR cells to vincristine (VCR) (a) and mitoxantrone (MXR) (b) was determined in the presence of different concentrations of erlotinib: 0.15 µmol/L, open triangles; 0.5 µmol/L, open diamonds; 1.5 µmol/L, open squares. The sensitivity of K562 (open circles) and K562/MDR (filled circles) cells to VCR (a) and MXR (b) was also determined in the absence of erlotinib. Cell growth inhibition following 5 days of culture was determined using the MTT assay. Growth inhibition curves were established from the means ± SD of triplicate determinations. Similar cell growth inhibition assays were performed using paclitaxel (PTX) and doxorubicin (DOX) in the presence of erlotinib or verapamil (0.05, 0.15, 0.5, and 1.5 µmol/L). Relative resistance to PTX (open diamonds), VCR (open squares), DOX (filled triangles), and MXR (filled circles) in the presence erlotinib (c) or verapamil (d) were calculated as the ratio of an IC50 value in the presence of an inhibitor divided by the IC50 value without inhibitors.

Variations in IC50 values for co‐treatments with erlotinib or verapamil and each anticancer drug were determined in order to compare their ability to inhibit P‐glycoprotein‐mediated resistance phenotypes (Fig. 3c,d). This assessment showed that verapamil, a typical MDR‐inhibitor, actually suppressed resistance to a series of drugs (VCR, PTX, DOX, and MXR) mediated by P‐glycoprotein at similar concentrations (Fig. 3d). In contrast, erlotinib‐induced reversal of P‐glycoprotein‐mediated resistance was different for individual anticancer drugs. Co‐treatment of K562/MDR cells with erlotinib at 1.5 µmol/L, which significantly suppressed resistance to both VCR and PTX (Fig. 3c, open squares and open diamonds respectively), did not affect resistance to DOX (Fig. 3c, filled triangles). Thus, the P‐glycoprotein‐mediated resistance to DOX was less sensitive to erlotinib‐mediated inhibition compared with resistance to VCR.

Remarkably, resistance to MXR was hardly affected by erlotinib, even at 5 µmol/L. Conversely, erlotinib co‐treatment (0.15–1.5 µmol/L) increased MXR resistance in K562/MDR cells (Fig. 3c, filled circles). We confirmed these bidirectional effects of erlotinib on P‐glycoprotein‐mediated resistance with two different methods: the MTT assay and a cell growth assay that counted cell numbers using a Coulter counter (data not shown). Both methods suggested that at clinical concentrations, erlotinib potentiated P‐glycoprotein‐mediated resistance to MXR in K562/MDR cells.

As shown in Table 2, calculated RI50 values of erlotinib treatment for P‐glycoprotein‐mediated resistance to each anticancer drug clearly showed that P‐glycoprotein‐mediated resistance to DOX and MXR was approximately 10‐fold less sensitive to erlotinib than observed for VCR and PTX. Conversely, verapamil reversed resistance to each of these drugs at comparable concentrations (RI50, 0.11–0.18 µmol/L). Therefore, the effects of erlotinib on P‐glycoprotein‐mediated resistance were quite different from those observed for verapamil and also from erlotinib effects on BCRP‐mediated resistance. Collectively, these data indicated that inhibitory ability of erlotinib was dependent upon the specific substrate in the P‐glycoprotein‐mediated resistance phenotype.

Table 2.

Values of RI50 (µM) to P‐glycoprotein‐mediated resistance

| Erlotinib | Verapamil | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| MDR | MXR | – | 0.18 ± 0.01 |

| DOX | 4.0 ± 0.2 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | |

| VCR | 0.37 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | |

| PTX | 0.44 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.03 |

Means ± SD. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

DOX, doxorubicin; MXR, mitoxantrone; PTX, paclitaxel; RI50, reversal indices; VCR, vincristine.

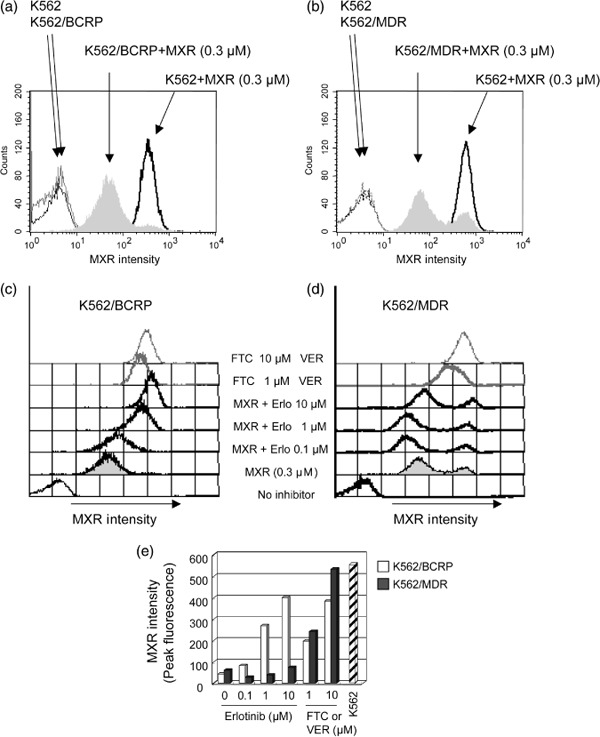

Effects of erlotinib on intracellular accumulation of mitoxantrone in cells expressing ABC transporters. The observations described above suggest that erlotinib may inhibit cellular efflux of MXR mediated by the ABC transporter BCRP, but not by P‐glycoprotein. The effects of erlotinib on the intracellular accumulation of MXR in BCRP‐ or P‐glycoprotein‐expressing K562 cells were examined by flow cytometric analysis. After incubating cells with 300 nmol/L MXR for 40 min, fluorescence intensity indicative of MXR uptake significantly increased in K562 cells, but only moderately increased in K562/BCRP and K562/MDR cells (Fig. 4a,b). These results indicated that BCRP and P‐glycoprotein exported MXR out of the cells.

Figure 4.

Effects of erlotinib on the intracellular accumulation of MXR. Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP)‐ and P‐glycoprotein‐mediated efflux reduces intracellular accumulation of mitoxantrone (MXR) (a and b). K562, K562/BCRP (a), and K562/MDR (b) cells were incubated for 40 min in the absence or presence of 0.3 µmol/L MXR, and then washed as described in ‘Materials and Methods’. Cellular uptake of MXR was determined as fluorescence intensity of MXR measured by flow cytometry. Modulation of MXR accumulation by erlotinib (c and d). K562/BCRP (c) and K562/MDR (d) cells were incubated with MXR (0.3 µmol/L) and inhibitory agents, erlotinib (0, 0.1, 1, and 10 µmol/L) or the selective inhibitor fumitremorgin C (FTC) (c, shaded lines) or verapamil (VER) (d, shaded lines) at 1 and 10 µmol/L for 40 min. Cellular uptake of MXR was measured as described above, and MXR levels were determined as peak fluorescence values. Intracellular MXR accumulation patterns are shown as change of peak fluorescence values (e). A peak fluorescence for K562 cells is shown as control (slash column).

Erlotinib co‐treatment enhanced MXR cellular fluorescence intensity in K562/BCRP cells in a dose‐dependent manner (Fig. 4c). The intracellular accumulation levels of MXR were determined by measuring peak fluorescence values at each point to compare efficacies of each inhibitor (Fig. 4e, with K562/BCRP cells shown as open columns). FTC or erlotinib at 10 µmol/L caused a similar enhancement of MXR accumulation in K562/BCRP cells, suggesting that erlotinib suppressed MXR efflux through BCRP with an efficacy that was similar to FTC.

Next, similar experiments were performed in K562/MDR cells to determine whether erlotinib modulates P‐glycoprotein‐mediated MXR transport (Fig. 4d). Consistent with its other effects on the P‐glycoprotein‐mediated resistance phenotype, co‐treatment with erlotinib at concentrations up to 10 µmol/L did not enhance MXR fluorescence intensity in K562/MDR cells (Fig. 4d,e). Instead, erlotinib at 0.1–1 µmol/L slightly reduced MXR fluorescence intensity, suggesting that erlotinib treatment stimulated the MXR efflux mediated by P‐glycoprotein. This effect of erlotinib on P‐glycoprotein was in agreement with a stimulation of MXR resistance by erlotinib co‐treatment in K562/MDR cells (Fig. 3b). Taken together, these results indicate that erlotinib suppressed MXR efflux mediated by BCRP, but not by P‐glycoprotein, in K562 cells.

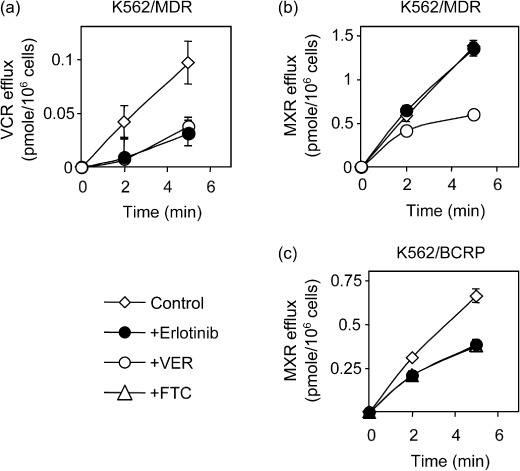

Effects of erlotinib on P‐glycoprotein‐mediated transport. Next we examined an effect of erlotinib on cellular efflux of VCR and MXR in K562/MDR and K562/BCRP cells (Fig. 5). Time course–dependent extracellular accumulations of [3H]VCR in the supernatants of K562/MDR cell samples were clearly suppressed by both erlotinib and verapamil at 10 µmol/L (Fig. 5a, closed and open circles respectively). These data indicated that P‐glycoprotein‐mediated VCR efflux was inhibited by erlotinib. However, similar experiments using MXR as a transporter substrate showed that erlotinib did not inhibit MXR efflux in K562/MDR cells (Fig. 5b) despite the fact that erlotinib suppressed BCRP‐mediated MXR efflux like FTC (Fig. 5c). These observations indicated that erlotinib sensitivity of P‐glycoprotein was dependent on the transporter substrate type.

Figure 5.

Effect of erlotinib on the cellular efflux vincristine (VCR) and mitoxantrone (MXR). K562/MDR (a and b) and K562/BCRP (c) cells were pre‐treated with 3H‐labeled substrates. Erlotinib, verapamil (VER), and fumitremorgin C (FTC) were tested to suppress efflux of incorporated substrate as described in ‘Materials and Methods’. The efflux of 3H‐labeled substrate was determined by measuring their radioactivity levels released into the culture medium. Data are the means ± SD of triplicate determinations.

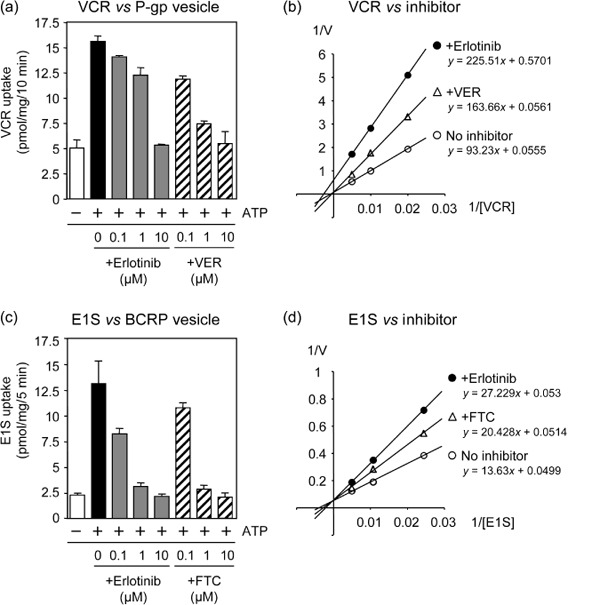

To understand the possible mechanism for substrate‐dependent erlotinib inhibition on P‐glycoprotein, intravesicular transport assay was performed to analyze kinetics of erlotinib inhibition on P‐glycoprotein‐mediated drug transport in vitro using membrane vesicles from K562/MDR cells. As shown in Figure 6a, ATP‐dependent [3H]VCR transport was actually inhibited by erlotinib in a dose‐dependent manner, although with less efficiency than by verapamil (IC50 values of erlotinib and verapamil were 2 and 0.2 µmol/L respectively). Moreover, Lineweaver‐Burk plot analysis showed that the inhibitory mode of erlotinib for P‐glycoprotein‐mediated VCR transport was a mixed type while that of verapamil was a competitive type (Fig. 6b). The calculated Vmax values (pmol/mg/min) were 18 in control, 1.8 in erlotinib (2 µmol/L)‐treated, and 17.8 in verapamil (0.2 µmol/L)‐treated samples respectively, and the calculated Ki value of verapamil was 270 nmol/L.

Figure 6.

The intracvesicular transports by P‐glycoprotein and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) and Lineweaver‐Burk plot analysis. Membrane vesicles from K562/MDR (a and b) and from K562/BCRP (c and d) cells were incubated for 10 min with [3H]VCR (a and b) and [3H]E1S (c and d) in the absence or presence of erlotinib, verapamil, or fumitremorgin C (FTC) as described in ‘Materials and Methods’. The concentration of 3H‐labeled transporter substrate was 100 or 50 nmol/L in the experiments (a) and (c), and those in (c) and (d) were 100, 200, 400 or 50, 100, 200 nmol/L respectively. Erlotinib at 2 µmol/L and verapamil (VER) at 0.2 µmol/L were tested in experiment (c), and erlotinib at 0.13 µmol/L and FTC at 0.25 µmol/L were in experiment (d). The transport of 3H‐labeled substrate was determined by measuring their radioactivity levels incorporated into the membrane vesicles. Data shown in (a) and (c) are the means ± SD of triplicate determinations, and data in (b) and (d) are the means of duplicated determinations.

The erlotinib effect on BCRP was also analyzed using membrane vesicles from K562/BCRP cells and [3H]estrone 3‐sulfate (E1S) as a transporter substrate of BCRP in an in vitro system. These experiments showed that both erlotinib and FTC inhibited BCRP‐mediated E1S transport with similar efficiency (IC50 values of erlotinib and FTC were 0.13 and 0.25 µmol/L respectively) (Fig. 6c). In this case, Lineweaver‐Burk plot analysis indicated that the calculated Vmax values (pmol/mg/min) in control, erlotinib (0.13 µmol/L)‐treated, and FTC (0.25 µmol/L)‐treated samples appeared to be at similar levels (20 in control, 18.9 in erlotinib treated, and 19.5 in FTC‐treated, respectively). The calculated Ki value of erlotinib was about 150 nmol/L and that of FTC was about 550 nmol/L to BCRP‐mediated E1S transport. Therefore, the inhibitory mode of erlotinib for BCRP‐mediated E1S transport looked a competitive type (Fig. 6d), which was different from that for P‐glycoprotein‐mediated VCR transport. Our data also suggested that erlotinib has stronger inhibitory activity to BCRP than FTC. Collectively, these results indicated that the inhibitory mechanism of erlotinib on the transporter function of P‐glycoprotein seemed different from that on the BCRP function.

Discussion

We have previously shown functional interplay between gefitinib and BCRP( 12 ) which suggested gefitinib as a competitor for other BCRP substrates, including SN‐38 and MXR. In the present study, we further demonstrated that erlotinib modulated BCRP‐mediated drug resistance and efflux at sub‐micromoler concentrations like a competitive inhibitor. Conversely, we found that erlotinib had only minimal effects on P‐glycoprotein‐mediated drug resistance to MXR and DOX, and even potentiated MXR resistance in K562/MDR cells at concentrations of 0.15–1.5 µmol/L. In addition, we demonstrated that erlotinib restored intracellular accumulation of MXR in BCRP‐expressing K562 cells, but did not in P‐glycoprotein‐expressing K562 cells. Furthermore, we showed that erlotinib selectively inhibited the P‐glycoprotein‐mediated efflux of VCR by a complicated mechanism, but not that of MXR. These data demonstrate for the first time that the bidirectional modulation of P‐glycoprotein‐mediated drug resistance by erlotinib is substrate dependent.

P‐glycoprotein drug interaction sites are thought to localize to the transmembrane domains, and the presence of multiple drug binding sites has been suggested.( 21 ) Although putative interaction sites for MXR and DOX are not well defined, the mode of interaction for DOX with P‐glycoprotein seems to be different from that of vinca alkaloids. Specifically, substitution of P‐glycoprotein Phe‐335 in transmembrane domain 6 with alanine resulted in a loss of resistance to vinblastine, but retention of resistance to DOX.( 22 ) The RI50 value of erlotinib for DOX resistance in K562/MDR cells was approximately 10‐fold higher than observed for VCR or PTX resistance (Table 2). Therefore, the region of P‐glycoprotein that interacts with erlotinib may be distinct from the DOX interaction site. Further molecular studies will be required to properly elucidate the modes of interaction between kinase inhibitors and P‐glycoprotein.

With regard to effects on BCRP by TKIs, previous studies have shown that gefitinib binds to ATP‐bound BCRP at an as yet undetermined binding site.( 23 ) Shi et al. recently reported that erlotinib did not compete with iodoarylazidoprazosin at the substrate‐binding sites on BCRP or P‐glycoprotein, although erlotinib stimulates the ATPase activity of both proteins.( 16 ) Since P‐glycoprotein and BCRP ATPase activities are stimulated by their substrates, and BCRP expression conferred resistance to erlotinib in PC‐9 cells, erlotinib may directly interact with an as yet undetermined site in BCRP and P‐glycoprotein and function like a substrate. Indeed, recent study suggests erlotinib as a substrate for both P‐glycoprotein and BCRP in vivo since P‐glycoprotein and BCRP significantly affect the oral bioavailability of erlotinib.( 24 )

Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) was more sensitive to the inhibitory effect of erlotinib than P‐glycoprotein, since the RI50 values of erlotinib for BCRP were lower than those for P‐glycoprotein (1, 2). Consistently, Shi et al. also showed that the ATPase activity of BCRP was stimulated by lower concentrations of erlotinib than were required for P‐glycoprotein.( 16 ) In addition, gefitinib has been shown to have a higher affinity for BCRP than for P‐glycoprotein.( 25 ) Collectively, these observations suggest that erlotinib will have a higher affinity for BCRP than for P‐glycoprotein.

Studies of erlotinib pharmacokinetics have shown that plasma concentrations of erlotinib are in the micromoler range in clinical situations.( 26 ) Given that erlotinib‐mediated modulation of BCRP and P‐glycoprotein function was achieved at sub‐micromoler levels in our experiments, erlotinib administration will likely affect the normal functions of BCRP and P‐glycoprotein expressed in digestive organs, the kidney, and the blood–brain barrier.

Erlotinib and other TKIs will likely be tested against various tumor types in combination with chemotherapy, but the benefits of such combination therapy are not yet apparent.( 27 ) Molecular analysis suggests that EGFR‐activation mutations found in some patients are correlated with the best outcome in combination therapy with EGFR‐TKIs and conventional anticancer drugs.( 28 ) Importantly, our findings demonstrate that the pharmacological effect of erlotinib on P‐glycoprotein varies among substrates. Further efforts for the understanding of pharmacological interaction between TKIs and anticancer drugs would be beneficial to improve the effectiveness of combination therapy.( 29 ) These preclinical studies on the TKIs, the ABC transporters, and their substrates would also contribute to prevent the occurrence of unexpected adverse effects when utilizing combinational chemotherapy.

Abbreviations

| ABC | ATP‐binding cassette |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| BCRP | breast cancer resistance protein |

| EGFR | epidermal growth factor receptor |

| IC50 | 50% inhibitory concentration |

| TKI | tyrosine kinase inhibitor |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grants‐in‐Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology; and from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan. We thank Yuka Shimomura for performing the initial experiments in this work and other laboratory members for their helpful discussions.

References

- 1. Gottesman MM, Fojo T, Bates SE. Multidrug resistance in cancer: role of ATP‐dependent transporters. Nat Rev Cancer 2002; 2: 48–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sugimoto Y, Tsukahara S, Ishikawa E, Mitsuhashi J. Breast cancer resistance protein: molecular target for anticancer drug resistance and pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics. Cancer Sci 2005; 96: 457–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Doyle LA, Ross DD. Multidrug resistance mediated by the breast cancer resistance protein BCRP (ABCG2). Oncogene 2003; 22: 7340–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tsuruo T, Iida H, Tsukagoshi S, Sakurai Y. Overcoming of vincristine resistance in P388 leukemia in vivo and in vitro through enhanced cytotoxicity of vincristine and vinblastine by verapamil. Cancer Res 1981; 41: 1967–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fojo T, Bates S. Strategies for reversing drug resistance. Oncogene 2003; 22: 7512–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rabindran SK, Ross DD, Doyle LA, Yang W, Greenberger LM. Fumitremorgin C reverses multidrug resistance in cells transfected with the breast cancer resistance protein. Cancer Res 2000; 60: 47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sugimoto Y, Tsukahara S, Imai Y, Ueda K, Tsuruo T. Reversal of breast cancer resistance protein‐mediated drug resistance by estrogen antagonists and agonists. Mol Cancer Ther 2003; 2: 105–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Katayama K, Masuyama K, Yoshioka S, Hasegawa H, Mitsuhashi J, Sugimoto Y. Flavonoids inhibit breast cancer resistance protein‐mediated drug resistance: transporter specificity and structure‐activity relationship. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2007; 60: 789–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kumar A, Petri ET, Halmos B, Boggon TJ. Structure and clinical relevance of the epidermal growth factor receptor in human cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 1742–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harari PM, Allen GW, Bonner JA. Biology of interactions: antiepidermal growth factor receptor agents. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 4057–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mukai M, Che XF, Furukawa T et al . Reversal of the resistance to STI571 in human chronic myelogenous leukemia K562 cells. Cancer Sci 2003; 94: 557–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yanase K, Tsukahara S, Asada S, Ishikawa E, Imai Y, Sugimoto Y. Gefitinib reverses breast cancer resistance protein‐mediated drug resistance. Mol Cancer Ther 2004; 3: 1119–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Perez‐Soler R. Erlotinib: recent clinical results and ongoing studies in non small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13: s4589–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cohen MH, Johnson JR, Chen YF, Sridhara R, Pazdur R. FDA drug approval summary: erlotinib (Tarceva) tablets. Oncologist 2005; 10: 461–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J et al . Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 1960–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shi Z, Peng XX, Kim IW et al . Erlotinib (Tarceva, OSI‐774) antagonizes ATP‐binding cassette subfamily B member 1 and ATP‐binding cassette subfamily G member 2‐mediated drug resistance. Cancer Res 2007; 67: 11012–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shi Z, Parmar S, Peng XX et al . The epidermal growth factor tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG1478 and erlotinib reverse ABCG2‐mediated drug resistance. Oncol Rep 2009; 21: 483–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sugimoto Y, Sato S, Tsukahara S et al . Coexpression of a multidrug resistance gene (MDR1) and herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene in a bicistronic retroviral vector Ha‐MDR‐IRES‐TK allows selective killing of MDR1‐transduced human tumors transplanted in nude mice. Cancer Gene Ther 1997; 4: 51–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Naito M, Hamada H, Tsuruo T. ATP/Mg2+‐dependent binding of vincristine to the plasma membrane of multidrug‐resistant K562 cells. J Biol Chem 1988; 263: 11887–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Arao T, Fukumoto H, Takeda M, Tamura T, Saijo N, Nishio K. Small in‐frame deletion in the epidermal growth factor receptor as a target for ZD6474. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 9101–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Loo TW, Clarke DM. Mutational analysis of ABC proteins. Arch Biochem Biophys 2008; 476: 51–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Loo TW, Clarke DM. Functional consequences of phenylalanine mutations in the predicted transmembrane domain of P‐glycoprotein. J Biol Chem 1993; 268: 19965–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Saito H, Hirano H, Nakagawa H et al . A new strategy of high‐speed screening and quantitative structure‐activity relationship analysis to evaluate human ATP‐binding cassette transporter ABCG2‐drug interactions. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2006; 317: 1114–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Marchetti S, De Vries NA, Buckle T et al . Effect of the ATP‐binding cassette drug transporters ABCB1, ABCG2, and ABCC2 on erlotinib hydrochloride (Tarceva) disposition in in vitro and in vivo pharmacokinetic studies employing Bcrp1‐/‐/Mdr1a/1b‐/‐ (triple‐knockout) and wild‐type mice. Mol Cancer Ther 2008; 7: 2280–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ozvegy‐Laczka C, Hegedus T, Varady G et al . High‐affinity interaction of tyrosine kinase inhibitors with the ABCG2 multidrug transporter. Mol Pharmcol 2004; 65: 1485–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hamilton M, Wolf JL, Rusk J et al . Effects of smoking on the pharmacokinetics of erlotinib. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12: 2166–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Herbst RS, Prager D, Hermann R et al . TRIBUTE: a phase III trial of erlotinib hydrochloride (OSI‐774) combined with carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy in advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 5892–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bonomi PD, Buckingham L, Coon J. Selecting patients for treatment with epidermal growth factor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13: s4606–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Milano G, Spano JP, Leyland‐Jones B. EGFR‐targeting drugs in combination with cytotoxic agents: from bench to bedside, a contrasted reality. Br J Cancer 2008; 99: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]