Abstract

To improve the efficacy of sonodynamic therapy of cancer using photosensitizers, we developed a novel porphyrin derivative designated DCPH‐P‐Na(I) and investigated its photochemical characteristics and sonotoxicity on tumor cells. DCPH‐P‐Na(I) exhibited a minimum fluorescent emission by excitation with light, compared with a strong emission from ATX‐70, which is known to reveal both photo‐ and sonotoxicity. According to this observation, when human tumor cells were exposed to light in the presence of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) in vitro, the least phototoxicity was observed, in contrast to the strong phototoxicity of ATX‐70. However, DCPH‐P‐Na(I) exhibited a potent sonotoxicity on tumor cells by irradiation with ultrasound in vitro. This sonotoxicity was reduced by the addition of L‐histidine, but not D‐mannitol, thus suggesting that singlet oxygen may be responsible for the sonotoxicity of DCPH‐P‐Na(I). DCPH‐P‐Na(I) demonstrated significant sonotoxicity against a variety of cancer cell lines derived from different tissues. In addition, in a mouse xenograft model, a potent growth inhibition of the tumor was observed using sonication after the administration of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) to the mouse. These results suggest that sonodynamic therapy with DCPH‐P‐Na(I) may therefore be a useful clinical treatment for cancers located deep in the human body without inducing skin sensitivity, which tends to be a major side‐effect of photosensitizers. (Cancer Sci 2007; 98: 916–920)

Photodynamic therapy (PDT), a useful technique for the treatment of cancer, involves the administration of a photosensitizer, followed by its activation by visible light with a wavelength specific to the absorption of the photosensitizer.( 1 , 2 ) In the presence of oxygen, this activated photosensitizer can generate reactive oxygen species that cause the apoptosis and/or necrosis of tumor cells.( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ) Because it is a non‐invasive, highly localized, and relatively safe form of therapy, PDT has been clinically applied to various types of cancer. For example, the photosensitizer photofrin, a porphyrin derivative, is approved for use in cancer, including esophageal,( 5 ) breast,( 6 ) lung,( 7 ) bladder,( 8 ) and cervical cancer,( 9 ) and some encouraging results of clinical studies have thus been reported. Contrary to these advantages, PDT has two recognized drawbacks: (i) PDT can be applied only to the superficial lesions of tissues because of the limited penetration of light into tumor tissue,( 1 , 2 ) and (ii) PDT‐treated patients tend to suffer long‐lasting skin sensitivity due to the retention of photosensitizers in cutaneous tissues, so that they need to spend several weeks in the dark after such treatment in order to avoid sunlight.( 1 , 2 )

Recently, a new approach called sonodynamic therapy (SDT), in which the activation of photosensitizers is carried out using ultrasound irradiation, has been introduced to overcome the minimal tissue penetrating ability of light in PDT.( 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ) Ultrasound can penetrate deeply into tissues and can be focused into a small region of the tumor to activate a sonosensitizer.( 11 ) Although this feature of ultrasound is expected to result in an improvement of the tumoricidal effects of PDT, the skin sensitivity caused by photosensitizers still remains to be solved.

In the present study, we tried to produce a new porphyrin derivative that is activated by ultrasound but not by light in order to reduce the skin sensitivity. The photochemical and cytotoxic properties of the newly established sonosensitizer, designated DCPH‐P‐Na(I), were evaluated in vitro and in vivo for its potential use in SDT of tumors.

Materials and Methods

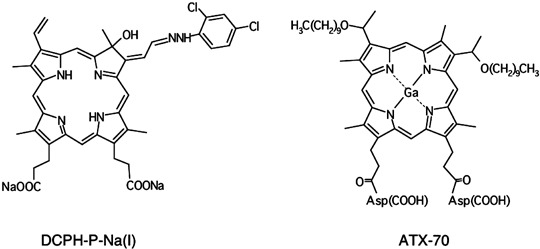

Reagents. DCPH‐P‐Na(I)[13,17‐bis(1‐carboxyethyl)‐8‐[2‐(2,4‐dichlorophenyl‐hydrazono)ethylidene]‐3‐ethenyl‐7‐hydroxy‐2,7,12,18‐tetramethylchlorin, disodium salt] (Fig. 1a) was synthesized from protoporphyrin IX dimethyl ester in three steps, including the condensation reaction with 2,4‐dichlorophenylhydrazine followed by hydrolysis. ATX‐70[7,12‐bis(1‐decyloxyethyl)‐2,18‐bispropionylaspartic acid 3,8,13, 17‐tetramethyl‐porphynate gallium(III) salt] (Fig. 1b) has been described previously.( 10 , 13 ) PureBright MB‐37‐50T [2‐(methacryloyloxyethyl)‐2′‐(trimethyl‐ammoniumethyl) phosphate, inner salt‐n‐butyl methacrylate copolymer], a solvent to dissolve drugs with a low aqueous solubility,( 14 ) was obtained from the NOF Co. (Tokyo, Japan).

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) and ATX‐70.

Mice. Balb/c athymic nude mice were obtained from Clea Japan (Tokyo, Japan). All experiments with these mice were carried out with the approval of the Fukuoka University Experimental Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cell culture. Human lung cancer cell lines, LU65A, RERFLC‐KJ, HLC‐1, VMRC, and KNS‐62, human gastric cancer cell lines, MKN‐1, MKN‐28, MKN‐45, MKN‐74, and KATO‐III, a human pancreas cell line, QGP‐1, and a human prostate cancer cell line, PC‐3, were obtained from the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources (Osaka, Japan). A human liver cancer cell line, KIM‐1, was from Kurume University (Kurume, Japan). Human colon cancer cell lines, HT‐29, T‐8, and Caco‐2, and a human breast cancer cell line, MDA‐MB‐435S, were from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). HLC‐1, VMRC, MKN‐1, MKN‐28, MKN‐45, MKN‐74, KATO‐III, QGP‐1, KIM‐1, MDA‐MB‐435S, HT‐29, T‐84 and Caco‐2 were maintained in DMEM (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Life Technologies, Rockville, MD, USA), 100 IU/mL of penicillin and 100 µg/mL of streptomycin. LU65A, RERFLC‐KJ and KNS‐62 were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Sigma Chemical) supplemented with FCS and antibiotics. PC‐3 was maintained in HAM's F‐12K (Sigma Chemical) supplemented with FCS and antibiotics.

Spectrophotometric assay. The absorbance spectra of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) and ATX‐70 were scanned in phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) with a spectrophotometer (SmartSpec Plus; Bio‐Rad Laboratory, Hercules, CA, USA). The excitation and emission spectra of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) and ATX‐70 were recorded using a spectrofluorophotometer (RF 5000; Simadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan).

Phototoxicity of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) and ATX‐70 in vitro. MKN‐45 cells (2 × 105) were incubated in 1 mL of PBS containing 5 µM DCPH‐P‐Na(I) or ATX‐70 in a well of 48‐well plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA). The cells were exposed to the light of a halogen lamp (MHAA‐100 W; Kenis Ltd, Osaka, Japan) at 60 klux for 10 min at room temperature. After the cells were centrifuged and resuspended in DMEM, their viability was then determined using the CellTiter 96 non‐radioactive cell proliferation assay kit (Promega Corp., Madison, WI, USA).

Sonotoxicity of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) in vitro. The ultrasound exposure of the cells in vitro was carried out under a dim light according to the previously described method.( 13 ) Briefly, tumor cells (2 × 105) were suspended in air‐saturated 1 mL PBS containing different concentrations (0.5–5.0 µM) of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) in a well of 48‐well plates at room temperature. The cells were exposed to different intensities (1 MHz, 0.5–2.0 W/cm2, 50% duty cycle) of ultrasound at room temperature using an ultrasound transducer (Sonitron 1000; RICH‐MAR, Inola, OK, USA) by immersing the head of the transducer directly into a cell suspension that was stirred at 250 r.p.m. with a miniature bar and a magnet stirrer. The viability of the cells was determined as described above.

Identification of reactive oxygen. L‐histidine hydrochloride monohydrate (Wako, Osaka, Japan) and D‐mannitol (Nacalai Chemicals, Ltd, Kyoto, Japan), scavengers of reactive oxygen species,( 15 , 16 ) were added at 0.2 M to the cell suspension in PBS containing MKN‐45 and 5 µM DCPH‐P‐Na(I), which was sonicated using Sonitron 1000 at 1.0 MHz, 1.0 W/cm2 output intensity and a 50% duty cycle for 1 min before determining the cell viability. The L‐histidine hydrochloride solution was neutralized with 10 N NaOH before use.

Anti‐tumor effect of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) in a mouse xenograft model. The in vivo antitumor effects of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) against human tumor cells were analyzed using a mouse xenograft model. MKN‐45 cells, 5 × 106 in 0.1 mL PBS, were subcutaneously injected into the backs of nude mice and led to tumors with a diameter of approximately 5 mm. DCPH‐P‐Na(I) dissolved in 0.5 mL PBS containing 1% PureBright was administered intravenously from a tail vein. After 24 h, the ultrasound conducting gel (Aloe‐Sound Lotion; RICH‐MAR) was placed between the tumor and the ultrasound probe, and ultrasound irradiation was then given for 10 min at 1 MHz, with two different intensities (1.0 or 2.0 W/cm2) and a 50% duty cycle. The tumor size was measured every 2 days on perpendicular axes and the mean tumor volume ± SE was calculated using the formula [length (mm) × width2 (mm2)]/2. The mice were then periodically observed for skin sensitivity and other changes in appearance and behavior.

Results

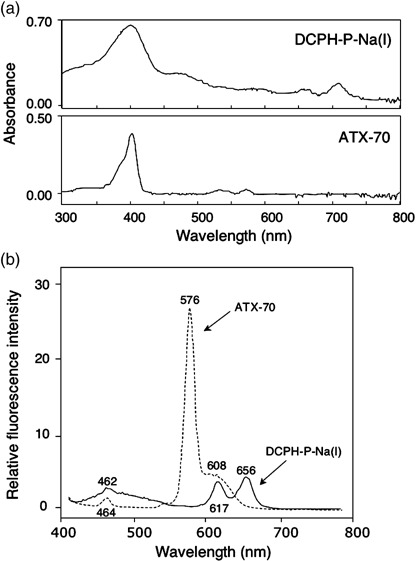

Spectrophotometric analysis of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) and ATX‐70. DCPH‐P‐Na(I) and ATX‐70 showed similar absorbance spectra with peaks at approximately 400 nm (Fig. 2a), which are most likely specific to the core structure of porphyrin. When DCPH‐P‐Na(I) was excited at 400 nm, its fluorescent peak emission observed at 656 nm was considerably lower than that observed at 576 nm for ATX‐70 (Fig. 2b), thus suggesting that DCPH‐P‐Na(I) displays minimal photosensitivity, whereas ATX‐70 revealed both photo‐ and sonosensitivities.( 10 , 13 )

Figure 2.

(a) Absorption spectra of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) and ATX‐70. (b) Fluorescence spectra of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) and ATX‐70 upon excitation at 400 nm.

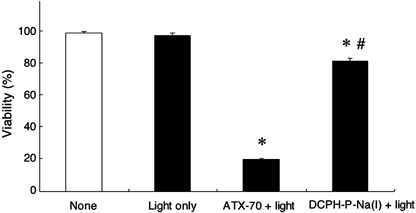

In vitro phototoxicity of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) and ATX‐70 on tumor cells. To examine the phototoxicity of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) in vitro, we exposed MKN‐45 cells to the light source in the presence of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) or ATX‐70. As shown in Fig. 3, DCPH‐P‐Na(I) exhibited a minimal phototoxicity in comparison to the intense phototoxicity of ATX‐70, which killed more than 80% of the cells.

Figure 3.

In vitro phototoxicity of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) and ATX‐70 on MKN‐45 tumor cells. MKN‐45 cells suspended in phosphate‐buffered saline containing 5.0 µM DCPH‐P‐Na(I) or ATX‐70 were exposed to 60 klux of light for 10 min and cell viability was measured using MTT assay as described in the Materials and Methods section. Data are the mean ± SD (n = 3). *Significantly different (P < 0.001) from the viability of the cells that received light only; #significantly different (P < 0.001) from the viability of the cells that received ATX‐70 and light (Dunnett test).

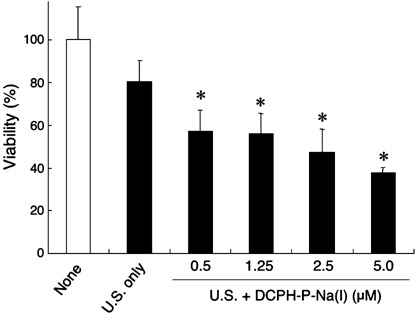

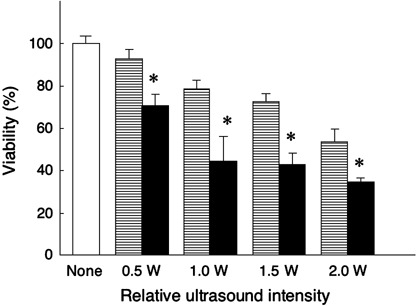

In vitro sonotoxicity of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) on tumor cells. When MKN‐45 cells in air‐saturated PBS were irradiated using ultrasound in the presence or absence of DCPH‐P‐Na(I), the minimum cytotoxicity using ultrasound alone was dose‐dependently and significantly increased by DCPH‐P‐Na(I) (Fig. 4). Thus, the maximum concentration (5.0 µM) of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) was used in the following in vitro study. This sonotoxicity of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) was also enhanced by augmenting the intensity of ultrasound (Fig. 5). However, the maximum difference in sonotoxicity between ultrasound exposure only and ultrasound exposure in the presence of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) was seen at an intensity of 1.0 W/cm2. Therefore we used this intensity in the following in vitro study. Treatment with sonication in the presence of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) immediately killed tumor cells and no sign of apoptosis was observed when analyzed using annexin V (data not shown). We next examined the sonotoxicity of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) on various tumor cells that originated from different tissues. As summarized in Table 1, these tumor cells showed different but considerable sensitivities against ultrasound in the presence of DCPH‐P‐Na(I). Without ultrasound irradiation, DCPH‐P‐Na(I) showed no cytotoxic effect on these tumor cells (data not shown).

Figure 4.

In vitro sonotoxicity of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) on MKN‐45 cell. MKN‐45 cells were suspended in air‐saturated phosphate‐buffered saline containing increasing amounts of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) and exposed to ultrasound (U.S.; 1.0 W/cm2) as described in the Materials and Methods section. Data are the mean ± SD (n = 8). *Significantly different (P < 0.01) from the U.S.‐only group (Dunnett test).

Figure 5.

The effect of irradiation intensity on sonotoxicity of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) against MKN‐45 cells. The cells were suspended in air‐saturated phosphate‐buffered saline containing 5.0 µM DCPH‐P‐Na(I) and then were exposed to ultrasound at increasing output intensities. Open bar, no treatment; horizontal stripes bar, ultrasound exposure only; solid bar, ultrasound exposure in the presence of DCPH‐P‐Na(I). Data are the mean ± SD (n = 8). *Significantly different (P < 0.01) from each set of ultrasound exposure only (Student's t‐test).

Table 1.

Sonotoxicity of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) on tumor cell lines derived from different organs

| Cell line | Origin | % Dead cells (± SD) | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| LU65A | Lung | 23.4 ± 12.1 | 4 |

| RERFLC‐KJ | 61.9 ± 4.3 | 8 | |

| HLC‐1 | 45.2 ± 4.9 | 4 | |

| VMRC‐LCP | 49.5 ± 7.8 | 4 | |

| KNS‐62 | 38.5 ± 10.9 | 4 | |

| MDA‐MB‐435S | Breast | 36.6 ± 5.9 | 4 |

| MKN‐1 | Stomach | 47.6 ± 9.3 | 8 |

| MKN‐28 | 28.0 ± 4.1 | 8 | |

| MKN‐45 | 61.4 ± 2.3 | 8 | |

| MKN‐74 | 41.3 ± 6.4 | 4 | |

| KATO‐III | 47.9 ± 2.2 | 4 | |

| QGP‐1 | Pancreas | 33.6 ± 6.9 | 8 |

| KIM‐1 | Liver | 46.5 ± 5.7 | 5 |

| HT‐29 | Colon | 36.3 ± 3.1 | 4 |

| T‐84 | 54.7 ± 6.5 | 8 | |

| Caco‐2 | 30.8 ± 6.9 | 4 | |

| PC‐3 | Prostate | 43.2 ± 3.2 | 8 |

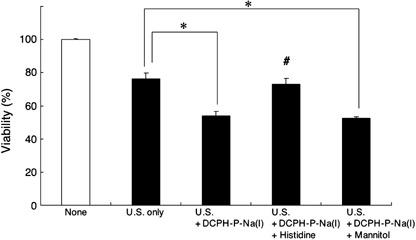

Detection of reactive oxygen species. To assess the possibility that the sonication in the presence of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) produces reactive oxygen species, we analyzed the effect of L‐histidine or D‐mannitol. As shown in Fig. 6, the enhanced killing of MKN‐45 cells by DCPH‐P‐Na(I) was completely blocked with 0.2 M L‐histidine, but not with D‐mannitol, thus suggesting that singlet oxygen plays a major role in the cell killing by ultrasound irradiation in the presence of DCPH‐P‐Na(I).

Figure 6.

Effect of oxygen scavengers on sonotoxicity of DCPH‐P‐Na(I). MKN‐45 cells were exposed to ultrasound (1.0 W/cm2) in phosphate‐buffered saline containing 5.0 µM DCPH‐P‐Na(I) with or without the oxygen scavengers, L‐histidine (0.2 M) or D‐mannitol (0.2 M). None, no treatment; U.S. only, cells were given ultrasound exposure only. Data are the mean ± SD (n = 4). *Significantly different (P < 0.01) from U.S. only; #significantly different (P < 0.01) from U.S. + DCPH‐P‐Na(I) and from U.S. + DCPH‐P‐Na(I) + Mannitol (Dunnett test).

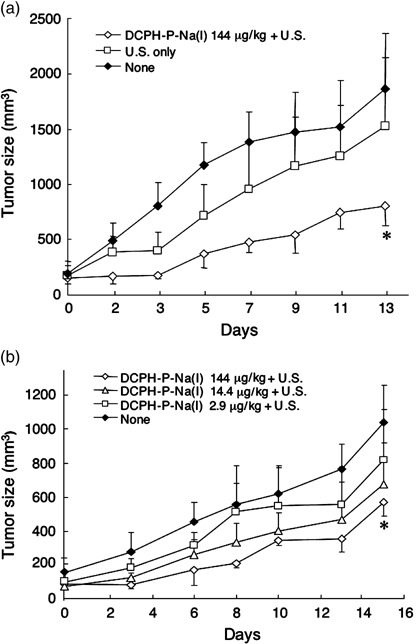

Sonotoxicity of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) on tumor cells in a mouse xenograft model. In a preliminary experiment, in which two different intensities (1.0 or 2.0 W/cm2) of ultrasound were tested in combination with DCPH‐P‐Na(I), significant tumor suppression was obtained only with 2.0 W/cm2 intensity (data not shown). Thus, we have used this intensity in the following in vivo study. Mice transplanted with MKN‐45 tumors were divided into three experimental groups, which were given either: (i) no treatment; (ii) ultrasound alone; or (iii) DCPH‐P‐Na(I) (144 µg [0.18 µmole]/kg of body weight) plus ultrasound. Within 13 days after the treatment, the growth of the MKN‐45 tumor was significantly inhibited by DCPH‐P‐Na(I) plus ultrasound in comparison to the group that received ultrasound alone (Fig. 7a). We next examined the dose‐dependency of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) for the sonotoxicity in vivo. MKN‐45 cells were transplanted into four groups of mice and each group of mice received either: (i) no treatment; (ii) DCPH‐P‐Na(I) (144 µg/kg of body weight) plus ultrasound; (iii) DCPH‐P‐Na(I) (14.4 µg/kg) plus ultrasound; or (iv) DCPH‐P‐Na(I) (2.9 µg/kg) plus ultrasound. The growth of the MKN‐45 tumor was significantly inhibited by 144 µg/kg DCPH‐P‐Na(I) within 15 days after the treatment in comparison to the control group (Fig. 7b), whereas no significant difference was observed for the group of mice that received either 14.4 or 2.9 µg/kg DCPH‐P‐Na(I). No apparent side‐effects, including skin sensitivity, were recognized in the mice injected with DCPH‐P‐Na(I).

Figure 7.

Antitumor effect of ultrasound‐activated DCPH‐P‐Na(I) in a mouse xenografted with MKN‐45 cells. (a) Balb/c athymic nude mice were subcutaneously inoculated with 5 × 106 MKN‐45 cells. After the development of tumor with a diameter of approximately 5 mm, the mice were given an intravenous injection of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) (Day 0). After 24 h (Day 1), the tumor was sonicated as described in the Materials and Methods section. None, no treatment group; U.S. only, ultrasound irradiation only; DCPH‐P‐Na(I) + U.S., ultrasound irradiation with DCPH‐P‐Na(I). Data are the mean ± SE (n = 5). *Significantly different (P < 0.01) from the other two groups (Student's t‐test). (b) After the tumor developed, the mice were given an intravenous injection of different amounts of DCPH‐P‐Na(I). After 24 h (Day 1), the tumor was sonicated with Sonitron 1000. Data are the mean ± SE (n = 5). *Significantly different (P < 0.01) from the non‐treatment group (Student's t‐test).

Discussion

We generated a novel sonosensitizer, DCPH‐P‐Na(I), with less photosensitivity to avoid skin sensitivity, a major adverse effect of photosensitizers. Potent sonotoxicity of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) was observed against the tumor cells in vitro, and significant growth inhibition of the tumor using sonotoxicity was also shown in a mouse xenograft model.

Photochemically active porphyrins, including photofrin II,( 11 ) ATX‐70,( 10 , 13 ) and ATX‐S10,( 16 ) have been demonstrated to induce cell killing when activated using ultrasound irradiation, thus indicating that these chemicals originally generated for PDT are therefore applicable as sonosensitizers to the tumor treatment in combination with ultrasound. However, skin sensitivity to sunlight is still a major side‐effect to be solved for photosensitizers. DCPH‐P‐Na(I) exhibited only a low‐emission spectrum pattern by excitation with light in comparison to the strong photosensitizer, ATX‐70 (Fig. 2), thus implying the reason why DCPH‐P‐Na(I) shows quite low levels of phototoxicity while also demonstrating effective sonotoxicity. The depth of tumor tissue damage in the body caused by SDT is expected to be far greater than that caused by PDT, which is limited to within a few millimeters from the surface.( 11 , 17 ) Therefore, SDT using DCPH‐P‐Na(I) might be applicable for the treatment of malignancies located fairly deep from the surface without inducing skin sensitivity.

In PDT, when a photosensitizer is exposed to specific wavelengths of light it is activated from its ground state into an exited state, and as the activated sensitizer turns to a ground state, the energy released can generate reactive oxygen species, such as singlet oxygen and free radicals, which mediate the direct cellular toxicity.( 18 ) The mechanism for the cytotoxicity in SDT seems to be theoretically similar to that in PDT. In SDT, it has been proposed that the activation of porphyrins through acoustic cavitation by ultrasound is attributed to the generation of active oxygens.( 12 , 19 , 20 ) In the present study, L‐histidine, a reactive oxygen scavenger of singlet oxygen and hydroxyl radicals,( 14 , 15 ) reduced the sonotoxicity of DCPH‐P‐Na(I), but D‐mannitol, a scavenger of hydroxyl radicals, hardly affected the sonotoxicity, thus suggesting that singlet oxygen is more important than hydroxyl radicals for the sonotoxicity of DCPH‐P‐Na(I).

Cell killing using PDT and SDT has been shown to be the result of either apoptosis and/or necrosis.( 3 , 4 ) We were unable to demonstrate that apoptosis is involved in the sonotoxicity of DCPH‐P‐Na(I). Previous studies have shown that the mode of cell death depends on different experimental conditions, including the cell type, the concentration of photosensitizers, and incubation conditions.( 21 , 22 , 23 ) Besides its direct phototoxicity to tumor cells, PDT affects the tumor vasculature so that the supply of oxygen and nutrients to tumor cells is hampered,( 24 , 25 ) while also stimulating the immune systems by inducing inflammation at the irradiated site.( 26 , 27 ) These secondary antitumor effects of PDT are also expected for SDT when using DCPH‐P‐Na(I).

Photosensitizers, which mainly develop based on the porphyrin structure, tend to be localized in tumors.( 1 , 2 , 28 ) The mechanisms for this selective accumulation of photosensitizers in tumors have been explained by their high permeability through the membranes, their affinity for proliferating endothelium, and their lack of lymphatic drainage in such tumors.( 29 ) DCPH‐P‐Na(I), with a similar structure to other porphyrin‐based photosensitizers, is also expected to accumulate in tumors, although the physiological properties and the pharmacological dynamics of DCPH‐P‐Na(I) in vivo still remain to be clarified.

In conclusion, the novel sonosensitizer DCPH‐P‐Na(I) has a great advantage for SDT over previous photosensitizers in relation to its minimal photosensitivity and may therefore be a useful tool for the treatment of cancer located too deep to be treated using regular PDT.

References

- 1. Sibata C, Colussi VC, Oleinick NL, Kinsella TJ. Photodynamic therapy in oncology. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2001; 2: 917–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dolmans DE, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Photodynamic therapy for cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2003; 3: 380–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oleinick NL, Morris RL, Belichenko I. The role of apoptosis in response to photodynamic therapy: what, where, why, how. Photochem Photobiol Sci 2002; 1: 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dellinger M. Apoptosis or necrosis following Photofrin photosensitization: influence of the incubation protocol. Photochem Photobiol 1996; 64: 182–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maunoury V, Mordon S, Bulois P, Mirabel X, Hecquet B, Mariette C. Photodynamic therapy for early esophageal cancer. Dig Liver Dis 2005; 37: 491–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cuenca RE, Allison RR, Sibata C, Downie GH. Breast cancer with chest wall progression: treatment with photodynamic therapy. Ann Surg Oncol 2004; 11: 322–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jones BU, Helmy M, Brenner M et al. Photodynamic therapy for patients with advanced non‐small‐cell carcinoma of the lung. Clin Lung Cancer 2001; 3: 37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Manyak MJ, Ogan K. Photodynamic therapy for refractory superficial bladder cancer: long‐term clinical outcomes of single treatment using intravesical diffusion medium. J Endourol 2003; 17: 633–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yamaguchi S, Tsuda H, Takemori M et al. Photodynamic therapy for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Oncology 2005; 69: 110–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Umemura S, Yumita N, Nishigaki R. Enhancement of ultrasonically induced cell damage by a gallium‐porphyrin complex, ATX‐70. Jpn J Cancer Res 1993; 84: 582–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yumita N, Umemura S. Sonodynamic therapy with photofrin II on AH130 solid tumor. Pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution and sonodynamic antitumoral efficacy of photofrin II. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2003; 51: 174–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yumita N, Sakata I, Nakajima S, Umemura S. Ultrasonically induced cell damage and active oxygen generation by 4‐formyloximethylidene‐3‐hydroxyl‐2‐vinyl‐deuterio‐porphynyl (IX)‐6‐7‐diaspartic acid. on the mechanism of sonodynamic activation. Biochim Biophys Acta 2003; 1620: 179–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abe H, Kuroki Mo Tachibana K, Li T et al. Targeted sonodynamic therapy of cancer using a photosensitizer conjugated with antibody against carcinoembryonic antigen. Anticancer Res 2002; 22: 1575–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Konno T, Watanabe J, Ishihara K. Enhanced solubility of paclitaxel using water‐soluble and biocompatible 2‐methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine polymers. J Biomed Mater Res 2003; 65A: 210–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huang D, Okada K, Komori C, Itoi E, Suzuki T. Enhanced antitumor activity of ultrasonic irradiation in the presence of new quinolone antibiotics in vitro . Cancer Sci 2004; 95: 845–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yumita N, Nishigaki R, Sakata I, Nakajima S, Umemura S. Sonodynamically induced antitumor effect of 4‐formyloximethylidene‐3‐hydroxy‐2‐vinyl‐deuterio‐porphynyl (IX)‐6,7‐diaspartic acid (ATX‐S10). Jpn J Cancer Res 2000; 91: 255–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Giercksky KE. Photodynamic therapy of superficial basal cell carcinoma with 5‐aminolevulinic acid with dimethylsulfoxide and ethylendiaminetetraacetic acid: a comparison of two light sources. Photochem Photobiol 2000; 71: 724–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pervaiz S. Reactive oxygen‐dependent production of novel photochemotherapeutic agents. FASEB J 2001; 15: 612–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rosenthal I, Sostaric JZ, Riesz P. Sonodynamic therapy – a review of the synergistic effects of drugs and ultrasound. Ultrason Sonochem 2004; 11: 349–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Okada K, Itoi E, Miyakoshi N, Nakajima M, Suzuki T, Nishida J. Enhanced antitumor effect of ultrasound in the presence of piroxicam in a mouse air pouch model. Jpn J Cancer Res 2002; 93: 216–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kessel D, Luo Y. Mitochondrial photodamage and PDT‐induced apoptosis. J Photochem Photobiol B 1998; 42: 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wyld L, Reed MWR, Brown NJ. Differential cell death response to photodynamic therapy is dependent on dose and cell type. Br J Cancer 2001; 84: 1384–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Noodt BB, Berg K, Stokke T, Peng Q, Nesland JM. Different apoptotic pathways are induced from various intracellular sites by tetraphenylporphyrins and light. Br J Cancer 1999; 79: 72–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Krammer B. Vascular effects of photodynamic therapy. Anticancer Res 2001; 21: 4271–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dolmans DE, Kadambi A, Hill JS et al. Vascular accumulation of a novel photosensitizer, MV6401, causes selective thrombosis in tumor vessels after photodynamic therapy. Cancer Res 2002; 62: 2151–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Korbelik M. Induction of tumor immunity by photodynamic therapy. J Clin Laser Med Surg 1996; 14: 329–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Van Duijnhoven FH, Aalbers RI, Rovers JP, Terpstra OT, Kuppen PJ. The immunological consequences of photodynamic treatment of cancer, a literature review. Immunobiology 2003; 207: 105–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hamblin MR, Newman EL. On the mechanism of the tumour‐localising effect in photodynamic therapy. J Photochem Photobiol B 1994; 23: 3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dougherty TJ, Gomer CJ, Henderson BW et al. Photodynamic therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998; 90: 889–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]