Abstract

A major impediment to cancer treatment is the development of resistance by the tumor. P‐glycoprotein (P‐gp) and multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1) are involved in multidrug resistance. In addition to the extrusion of chemotherapeutic agents through these transporters, it has been reported that there are differences in the intracellular distribution of chemotherapeutic agents between drug resistant cells and sensitive cells. Cepharanthine is a plant alkaloid that effectively reverses resistance to anticancer agents. It has been previously shown that cepharanthine is an effective agent for the reversal of resistance in P‐gp‐overexpressing cells. Cepharanthine has also been reported to have numerous pharmacological effects besides the inhibition of P‐gp. It has also been found that cepharanthine enhanced sensitivity to doxorubicin (ADM) and vincristine (VCR), and enhanced apoptosis induced by ADM and VCR of P‐gp negative K562 cells. Cepharanthine changed the distribution of ADM from cytoplasmic vesicles to nucleoplasm in K562 cells by inhibiting the acidification of cytoplasmic organelles. Cepharanthine in combination with ADM should be useful for treating patients with tumors. (Cancer Sci 2005; 96: 372–376)

Drug resistance is a one of the main obstacles to the successful treatment of cancer. Multidrug resistance (MDR) is often characterized by a decrease in the intracellular accumulation of anticancer agents and overexpression of P‐glycoprotein (P‐gp) and multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1), which belong to the superfamily of ATP‐binding cassette (ABC) transporters. These transporters are involved in ATP‐dependent efflux of the cytotoxic agents from the cells.( 1 , 2 ) However, in addition to the extrusion of drugs by ABC transporters, acidic organelles (trans‐Golgi network, the recycling endosomes, and the lysosomes) may also play a role in decreasing the cytotoxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs in several cultured MDR cell models.

Cellular pH in tumor‐derived cells was measured in several studies. The vesicles in which drugs accumulated have been identified as lysosomes,( 3 , 4 ) endosomes,( 5 ) and vesicles of the Golgi compartment,( 6 , 7 ) all of which are acidic organelles. Many anticancer agents, such as doxorubicin (ADM), daunorubin, vincristine (VCR), and mitoxantrone, are weak bases with pKa values between 7.4 and 8.4.( 8 , 9 ) When these drugs accumulate in the acidic compartments of the cell, they become protonated and sequestered within these compartments.( 10 ) Agents that disrupt organelle acidification should increase drug sensitivity. Treatments of resistant cells with reagents that are known to increase the pH of endomembrane compartments block the vesicular accumulation of chemotherapeutic drugs( 4 , 5 ) and increase the cytotoxicity of anticancer agents.

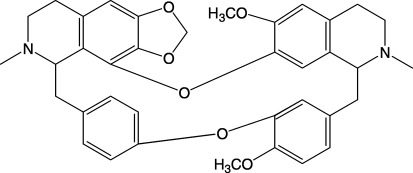

Cepharanthine (6′,12′‐dimethoxy‐2,2′‐dimethyl‐6,7‐[methylenebis(oxy)]oxyacanthan) is a biscoclaurine alkaloid extracted from the roots of Stephania cepharantha Hayata,( 11 ) and its structure is shown in Fig. 1. It is known as a membrane‐interacting agent with membrane‐stabilizing activity,( 12 ) and is widely used in Japan for the treatment of snake venom‐induced hemolysis, nasal allergy, leukopenia induced by anticancer drugs and radiation therapy. Cepharanthine reversed multidrug resistance directly interacting with P‐gp and possibly binding to phosphatidylserine in the membrane and disturbing the plasma membrane function.( 13 , 14 , 15 )

Figure 1.

Structure of cepharanthine.

However, we found that cepharanthine not only reversed the multidrug resistance mediated by P‐gp, but also enhanced the cytotoxic effect of anticancer agents on the drug sensitive parental cells.( 16 ) The mechanism of the cytotoxic enhancing function in a P‐gp‐negative K562 cell line was studied in the present paper.

Materials and methods

Cell line and chemicals. K562, a human chronic myelogenous leukemia cell line was kindly provided by Dr Sugimoto (Cancer Chemotherapy Center, Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research). RPMI 1640 medium was purchased from Nissui Seiyaku (Tokyo, Japan). Cepharanthine was kindly donated by Kaken Pharmaceutical, Osaka, Japan. Acridine Orange (AO), ADM and VCR were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO).

Cell culture. K562 cells and MIA‐PaCa‐2 human pancreatic cancer cells were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM glutamine and 100 units/mL of penicillin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. Cell cultures were maintained at exponential growth by replacing the media every 2–3 days. Culture medium was replaced with fresh medium the day before the experiment.

Measurement of the cellular content of AO by flow cytometry. K562 cells (1 × 106) were incubated with 0, 10, 25, and 50 µM of cepharanthine for 1 h at 37°C, then incubated with 6 µM AO for another 30 min, washed twice with PBS and the cells were resuspended in 1 mL PBS. The level of fluorescent staining of the cells was analyzed using a Beckman EPICS Flow Cytometry (Coulter Electronics, Hialeah, FL).

Measurement of apoptotic cells by flow cytometry. Apoptotic cells were quantitatively evaluated by flow cytometry. K562 cells (1 × 106) were incubated at 37°C with different concentrations of ADM or VCR for 24 h and with or without 5 µM cepharanthine, then the cells were harvested and washed twice with PBS. For flow cytometry, cells were suspended in 100 µL of PBS, thoroughly mixed with 100 µL of COULTER DNA‐Prep LPR (COULTER, Miami, FL), and then 2 mL of COULTER DNA‐Prep Stain was added and again mixed thoroughly. The mixture was incubated for 15 min in the dark at room temperature. The sub‐G1 fraction was determined as previously described.( 17 )

Determination of viability by the 3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl) ‐2,5‐diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) Assay. Chemosensitivity in vitro was measured with the MTT colorimetric assay in 96‐well plates. K562 (1 × 104) cells were incubated in culture medium with or without cepharanthine and various concentrations of VCR and ADM in a final volume of 100 µL. After 3 days, 10 µL of MTT (5 mg/mL in PBS) was added to each well and the plates were incubated for an additional 3 h. The resulting formazan was dissolved in 100 µL of isopropanol/0.04 N HCl. The plates were shaken mechanically for 5 min and read immediately at 570 nm using a model 550 Micro Plate Reader (Bio‐Rad, Richmond, CA).

Fluorescence and laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM). K562 MIA‐PaCa‐2 cells were incubated with 10 µM ADM in the presence or absence of 10 µM cepharantine for 60 min at 37°C. The cells were then washed three times in PBS and the samples on slides were examined by confocal microscopy (Leica TCS4D, Wetzlar, Germany). The fluorescence of ADM was observed with λex at 488 nm and λem at 600 nm. K562 cells were incubated at 37°C. The fluorescence of cepharanthine was observed with λex at 488 nm and λem at 530 nm. K562 cells were incubated with 6 µM AO for 30 min or sequentially with 20 µM cepharanthine for 30 min and 6 µM AO for 30 min at 37°C. After rinsing as above, the fluorescence of AO was examined by confocal microscopy with λex at 488 nm. Dual emission confocal images were simultaneously recorded with λem at 530/30 nm (green fluorescence) and λem at 600/long pass nm (red fluorescence).

Statistical analysis. Differences between groups were tested by 1‐way ANOVA. Data are presented as the means ± SD. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Effect of cepharanthine on cytotoxity of ADM and VCR. Cepharanthine is a plant alkaloid that effectively reverses P‐gp‐mediated MDR. We found in the previous paper that cepharanthine was not only an effective agent for the reversal of MDR mediated by P‐gp, but also enhanced the cytotoxic effect of anticancer agents on P‐gp‐negative parental cells. Cepharanthine induced caspase‐dependent and Fas‐independent apoptosis in Jurkat and K562 human leukemia cells.( 18 ) We examined the effect of cepharanthine on the cytotoxicity of ADM and VCR in the P‐gp negative K562 cells. The doses of ADM and VCR causing 50% inhibition of cell growth (IC50) were 1147.6 ± 40 and 3.9 ± 0.07 nM for K562 cells, respectively. However, in the presence of 2 µM cepharanthine that has no cytotoxic effects on K562 cells for 3 days, the IC50 of ADM and VCR decreased to 213.5 ± 4.33 and 0.9 ± 0.04 nM, respectively. K562 cells treated with cepharanthine were 5.4‐fold more sensitive to ADM and 4.4‐fold more sensitive to VCR than untreated K562 cells.

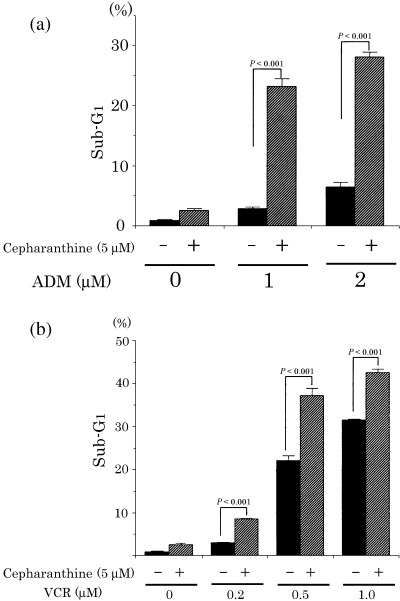

Effect of cepharanthine on ADM‐ and VCR‐induced apoptosis in K562 cells. We next investigated whether cepharanthine affects apoptosis induced by ADM or VCR in K652 cells. We treated K562 cells with ADM and VCR for 24 h in the absence or presence of cepharanthine (5 µM) and measured the sub‐G1 fraction by flow cytometric analysis. ADM and VCR increased the proportion of the sub‐G1 fraction of K562 cells in a dose‐dependent manner (Fig. 2). The proportion of the sub‐G1 fraction of cells treated with ADM (Fig. 2a) or VCR (Fig. 2b) in the presence of cepharanthine were significantly higher than that of cells treated with ADM or VCR alone. These findings indicate that cepharanthine enhances ADM‐ and VCR‐induced apoptosis.

Figure 2.

Effect of doxorubicin (ADM) and vincristine (VCR) on the proportion of the sub‐G1 fraction in K562 cells treated with cepharanthine. K562 cells were cultured for 24 h with ADM (a) or VCR (b) in the presence or absence of cepharanthine were stained with propidium iodide and examined for apoptosis using flow cytometric analyses. The proportion of the sub‐G1 fraction in K562 cells treated with cepharanthine was higher than in untreated K562 cells. Each value represents the mean of three independent experiments. Bars, SD.

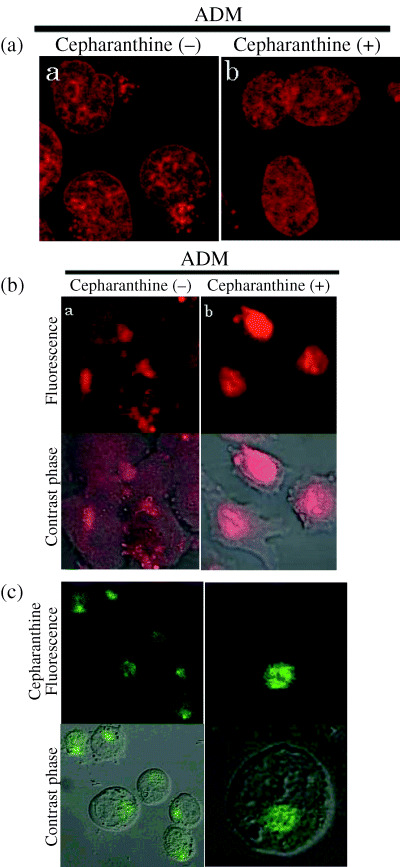

Effects of cepharanthine on intracelluar distribution of ADM in K562 cells and MIA‐PaCa‐2. Many anticancer drug‐resistant cell lines have the capacity to compartmentalize the drug away from intercellular target sites.( 19 ) In contrast, anticancer agents are concentrated to some extent within the nuclei in drug‐sensitive cells. We determined the effects of cepharanthine on the intracellular distribution of ADM. The cells were incubated at 37°C with ADM in the absence or presence of cepharanthine and examined without fixation by confocal laser microscopy (Fig. 3a). ADM was found in the nucleoplasm and cytoplasm of the cells in the absence of cepharanthine. In the presence of cepharanthine, the ADM in cytoplasmic vesicles shifted to the nucleoplasm in K562 cells (Fig. 3a). To examine whether cepharanthine has similar effects on other cells, we examined the intracellular localization of ADM in MIA‐PaCa‐2. In the presence of cepharanthine, the intracellular localization of ADM in cytoplasmic vesicles shifted to the nucleoplasm in MIA‐PaCa‐2 (Fig. 3b). We also examined the localization of cepharanthine in K562 cells by confocal laser microscopy. Cepharanthine was mainly seen in the punctuate cytoplasmic compartments (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

Effect of cepharanthine on the intracellular distribution of doxorubicin (ADM) in K562 cells or MIA‐PaCa‐2. K562 cells (a) or MIA‐PaCa‐2 cells (b) were incubated with 10 µM ADM in the presence or absence of 10 µM cepharantine for 60 min at 37°C. In K562 cells or MIA‐PaCa‐2 , ADM was found in the nucleoplasm and cytoplasm (a). In K562 cells or MIA‐PaCa‐2 treated with cepharanthine (10 µM), ADM was primarily localized within nuclei (b). Cepharanthine (10 µM) changed the distribution of ADM in K562 cells and MIA‐PaCa‐2 cells. (c) Localization of cepharanthine in K562 cells. K562 cells were incubated with 20 µM cepharanthine for 30 min at 37°C and examined the localization of cepharanthine by laser‐scanning confocal microscopy. Cepharanthine was localized in the punctuate cytoplasmic compartments.

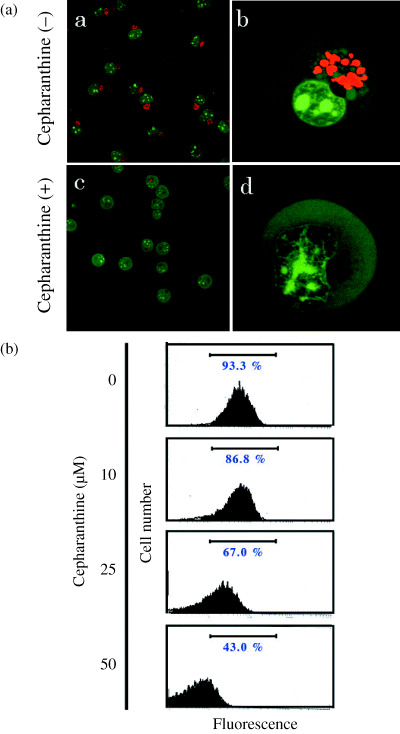

Effects of cepharanthine on acidification of intercellular organelles. ADM accumulates in acidified organelles of drug resistant cells.( 10 ) Acidification of organelle plays a direct role in the accumulation of weak bases such as ADM.( 5 ) To examine whether the cepharanthine‐induced accumulation of ADM in the nucleus were caused by the release of ADM from cytoplasmic organelles, the effects of cepharanthine on organelle acidification were examined (Fig. 4). AO is a weakly basic fluorescence probe that accumulates in the acidic organelles and emits green fluorescence at low concentration and red fluorescence at high concentration: this was used to detect acidic organelles.( 20 ) AO produced red fluorescence in the cytoplasm of K562 cells in the absence of cepharanthine. However, after incubation with cepharanthine for 30 min dramatically decreased red AO fluorescence in K562 cells (Fig. 4a), and this effect of cepharanthine was dose‐dependently augmented (Fig. 4b). These results suggest that cepharanthine attenuated organelle acidification in K562 cells.

Figure 4.

Effects of cepharanthine on organellar acidification in K562 cells. Acridine Orange (AO) accumulated in acidic compartments produces red fluorescence. (a) In K562 cells (a, b), AO produced red fluorescence in the cytoplasm. Red AO fluorescence was considerably diminished in the presence of 20 µM cepharanthine (c, d). (b) K562 cells were incubated with 10, 25 and 50 µM cepharanthine for 60 min. AO fluorescence was quantified by flow cytometry. Incubation with cepharanthine for 30 min decreased red AO fluorescence in K562 cells in a dose‐dependent manner.

Discussion

The resistance of tumor cells to anticancer agents remains a major cause of treatment failure in cancer patients. As most anticancer agents target DNA or nuclear enzymes, the sequestration of drugs in acidic vesicles, such as the trans‐Golgi network, the recycling endosomes, and the lysosomes, leads to decreased drug‐target interaction and therefore decreased cytotoxity, even if the intracellular drug concentration remains unchanged.( 19 )

Cepharanthine is known as a membrane‐interacting agent and has a membrane‐stabilizing activity. It is widely used in Japan for the treatment of snake venom‐induced hemolysis, nasal allergy and leukopenia induced by anticancer drugs and radiation therapy. It has been reported that cepharanthine reverses MDR mediated by P‐gp( 13 ) and restores the effect of anticancer drugs in multidrug‐resistant cancer cells possibly by disturbing the plasma membrane function and increasing the intercellular accumulation of anticancer drugs.( 21 ) Some reports have shown that cepharanthine inhibited the growth of Ehrlich ascites tumor,( 22 ) enhanced thermosensitivity in vitro,( 23 ) and induced apoptosis in Jurkat and K562 leukemia cells.( 18 , 24 ) However, the molecular basis for enhancement of the antitumor effect by cepharanthine is unknown.

In this study, we examined whether cepharanthine enhances cytotoxity and apoptosis induced by ADM and VCR in P‐gp negative K562 cells. Previous studies have shown that cepharanthine reversed P‐gp‐mediated drug resistance by competitively inhibiting the binding of anticancer agents to the drug‐binding site of P‐gp.( 16 ) Although K562 cells did not express P‐gp, cepharanthine at a non‐cytotoxic dose markedly enhanced the cytotoxicity of ADM and VCR in K562 cells. K562 cells treated with cepharanthine accumulated more ADM into nuclei compared with K562 cells without cepharanthine. These findings indicate that cepharanthine has other functions than the inhibition of P‐gp.

ADM localized in acidic organelles, such as lysosomes, the trans‐Golgi network and endosomes, has been observed in drug‐resistant cells.( 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ) In these cells, weak base chemotherapeutics accumulated in acidic organelles and sequestered from their molecular targets in the cytosol and nuclei.( 25 ) Cepharanthine blocked the acidification of organelles in K562 cells, and ADM may have been consequently released from the organelles into the nucleus. Cepharanthine preferentially accumulated into acidic vesicular compartments and might raise the intraluminal pH in acidic vesicular compartments. Although monensin, bafilomycin A1 and concanamycin A also inhibit organelle acidification,( 5 ) these agents are toxic for clinical use. However, cepharnathine has been clinically used.

The intracellular pH of mammalian cells is regulated mainly by Na+/H+ exchange and HCO3 −‐dependent transport mechanisms.( 26 ) In addition, vacuolar‐type H+‐ATPase may be expressed in the plasma membrane of certain tumor cells.( 27 ) This proton ATPase is responsible for acidification of the intracellular compartment in eukaryotic cells.( 28 ) Interestingly, it has been shown that at least one of the subunits of vacuolar proton ATPase is overexpressed in both VCR‐resistant and ADM‐resistant HL‐60 cells.( 29 , 30 ) The use of bafilomycin A1, an agent that selectively inhibits vacuolar proton ATPase, induced a major increase in drug accumulation and inhibited drug efflux in both VCR‐resistant and ADM‐resistant HL‐60 cells. The mechanisms by which cepharanthine inhibits the acidification of cytoplasmic organelles is not known at present. Morphological studies of HeLa cells treated with cepharanthine showed the presence of many electron‐dense lysosome‐like bodies.( 13 ) It has been recognized that certain cationic amphipathic drugs interfere lysosomal digestion and thereby induce storage, mainly polar lipids. Because cepharanthine is also cationic and amphipathic, it may be accumulated together with polar lipids in the electron‐dense lysosome‐like bodies. These effects of cepharanthine on lysosomes might change the function of membrane proteins such as vacuolar‐type H+‐ATPase by perturbing the membrane lipid bilayers.

This study shows that cepharanthine not only reversed P‐gp mediate MDR, but also inhibited the acidification of organelles. Cells treated with cepharanthine are able to accumulate significantly increased ADM in nuclei, resulting in increased cytotoxicity compared with cells untreated with cepharanthine. Cepharanthine may be a clinically useful agent to suppress the acidification of cytoplasmic organelles and may be a useful modifier for treating patients with ADM and VCR.

References

- 1. Gottesman MM, Pastan I. Biochemistry of multidrug resistance mediated by the multidrug transporter. Annu Rev Biochem 1993; 62: 385–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Deeley RG, Cole SP. Function, evolution and structure of multidrug resistance protein (MRP). Semin Cancer Biol 1997; 8: 193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Warren L, Jardillier JC, Ordentlich P. Secretion of lysosomal enzymes by drug‐sensitive and multiple drug‐resistant cells. Cancer Res 1991; 51: 1996–2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hurwitz SJ, Terashima M, Mizunuma N, Slapak CA. Vesicular anthracycline accumulation in doxorubicin‐selected U‐937 cells: participation of lysosomes. Blood 1997; 89: 3745–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Altan N, Chen Y, Schindler M, Simon SM. Defective acidification in human breast tumor cells and implications for chemotherapy. J Exp Med 1998; 187: 1583–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Klohs WD, Steinkampf RW. The effect of lysosomotropic agents and secretory inhibitors on anthracycline retention and activity in multiple drug‐resistant cells. Mol Pharmacol 1988; 34: 180–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lautier D, Bailly JD, Demur C, Herbert JM, Bousquet C, Laurent G. Altered intracellular distribution of daunorubicin in immature acute myeloid leukemia cells. Int J Cancer 1997; 71: 292–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Owellen RJ, Donigian DW, Hartke CA, Hains FO. Correlation of biologic data with physico‐chemical properties among the vinca alkaloids and their congeners. Biochem Pharmacol 1977; 26: 1213–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Skovsgaard T. Transport and binding of daunorubicin, adriamycin, and rubidazone in Ehrlich ascites tumour cells. Biochem Pharmacol 1977; 26: 215–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mayer LD, Bally MB, Cullis PR. Uptake of adriamycin into large unilamellar vesicles in response to a pH gradient. Biochim Biophys Acta 1986; 857: 123–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tomita M, Fujitani K, Aoyagi Y. Synthesis of di‐cetharanthine. Tetrahedron Lett 1967; 13: 1201–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Utsumi K, Miyahara M, Sugiyama K. Effect of biscoclaurine alkaloid on the cell membrane related to membrane fluidity. Acta Histochem Cytochem 1976; 9: 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shiraishi N, Akiyama S, Nakagawa M, Kobayashi M, Kuwano M. Effect of bisbenzylisoquinoline (biscoclaurine) alkaloids on multidrug resistance in KB human cancer cells. Cancer Res 1987; 47: 2413–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kato T, Suzumura Y. Potentiation of antitumor activity of vincristine by biscoclaurine alkaloid cepharahthine. J Natl Cancer Inst 1987; 79: 527–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nagaoka S, Kawasaki S, Karino Y, Sasaki K, Nakanishi T. Modification of cellular efflux and cytotoxicity of adriamycin by biscoclauline alkaloid in vitro. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 1987; 23: 1297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mukai M, Che XF, Furukawa T et al. Reversal of the resistance to STI571 in human chronic myelogenous leukemia K562 cells. Cancer Sci 2003; 94: 557–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ikeda R, Furukawa T, Kitazono M et al. Molecular basis for the inhibition of hypoxia‐induced apoptosis by 2‐deoxy‐D‐ribose. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2002; 291: 806–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wu J, Suzuki H, Akhand AA, Zhou YW, Hossain K, Nakashima I. Modes of activation of mitogen‐activated protein kinases and their roles in cepharanthine‐induced apoptosis in human leukemia cells. Cell Signal 2002; 14: 509–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Larsen AK, Escargueil AE, Skladanowski A. Resistance mechanisms associated with altered intracellular distribution of anticancer agents. Pharmacol Ther 2000; 85: 217–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schindler M, Grabski S, Hoff E, Simon SM. Defective pH regulation of acidic compartments in human breast cancer cells (MCF‐7) is normalized in adriamycin‐resistant cells (MCF‐7adr). Biochemistry 1996; 35: 2811–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kato T, Suzumura Y. Potentiation of antitumor activity of vincristine by the biscoclaurine alkaloid cepharanthine. J Natl Cancer Inst 1987; 79: 527–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Asaumi J, Nishikawa K, Matsuoka H et al. Direct antitumor effect of cepharanthin and combined effect with adriamycin against Ehrlich ascites tumor in mice. Anticancer Res 1995; 15: 67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang Y, Kuroda M, Gao XS et al. Cepharanthine enhances in vitro and in vivo thermosensitivity of a mouse fibrosarcoma, FSa‐II, based on increased apoptosis. Int J Mol Med 2004; 13: 405–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wu J, Suzuki H, Zhou YW et al. Cepharanthine activates caspases and induces apoptosis in Jurkat and K562 human leukemia cell lines. J Cell Biochem 2001; 82: 200–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Altan N, Chen Y, Schindler M, Simon SM. Tamoxifen inhibits acidification in cells independent of the estrogen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999; 96: 4432–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Durand T, Gallis JL, Masson S, Cozzone PJ, Canioni P. pH regulation in perfused rat liver. Respective role of Na(+)‐H+ exchanger and Na(+)‐HCO3‐ cotransport. Am J Physiol 1993; 265: G43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Martinez‐Zaguilan R, Lynch RM, Martinez GM, Gillies RJ. Vacuolar‐type H(+)‐ATPases are functionally expressed in plasma membranes of human tumor cells. Am J Physiol 1993; 265: C1015–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Forgac M. Structure and properties of the vacuolar (H+)‐ATPases. J Biol Chem 1999; 274: 12951–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marquardt D, Center MS. Involvement of vacuolar H(+)‐adenosine triphosphatase activity in multidrug resistance in HL60 cells. J Natl Cancer Inst 1991; 83: 1098–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marquardt D, Center MS. Drug transport mechanisms in HL60 cells isolated for resistance to adriamycin: evidence for nuclear drug accumulation and redistribution in resistant cells. Cancer Res 1992; 52: 3157–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]