Abstract

Intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of paclitaxel (PTX) is a hopeful therapeutic strategy for peritoneal malignancy. Intravenously (i.v.) injected nanoparticle anticancer drugs are known to be retained in the blood stream for a long time and favorably extravasated from vessels into the interstitium of tumor tissue. In this study, we evaluated the effect of i.p. injection of PTX (PTX‐30W), which was prepared by solubulization with water‐soluble amphiphilic polymer composed of PMB‐30W, a co‐polymer of 2‐methacryloxyethyl phosphorylcholineand n‐butyl methacrylate, for peritoneal dissemination of gastric cancer. In a peritoneal metastasis model with transfer of MKN45P in nude mice, the effct of i.p. administration of PTX‐30W was compared with conventional PTX dissolved in Cremophor EL (PTX‐Cre). The drug accumulation in peritoneal nodules was evaluated with intratumor PTX concentration and fluorescence microscopic observation. PTX‐30W reduced the number of metastatic nodules and tumor volume significantly more than did conventional PTX dissolved in Cremophor EL (PTX‐Cre), and prolonged the survival time (P < 0.05). PTX concentration in disseminated tumors measured by HPLC was higher in the PTX‐30W than in the PTX‐Cre group up to 24 h after i.p. injection. Oregon green–conjugated PTX‐30W, i.p. administered, preferentially accumulated in relatively hypovascular areas in the peripheral part of disseminated nodules, which was significantly greater than the accumulation of PTX‐Cre. I.p. administration of PTX‐30W may be a promising strategy for peritoneal dissemination, due to its superior characteristics to accumulate in peritoneal lesions. (Cancer Sci 2009; 100: 1979–1985)

Intra‐abdominal dissemination within the peritoneal cavity is a dreaded clinical condition in gastrointestinal and ovarian cancer. Particularly, in gastric cancer, peritoneal carcinomatosis is the commonest pattern of tumor progression and shows the worst prognosis among various recurrence patterns.( 1 , 2 ) Systemic chemotherapy is mainly performed as the treatment for peritoneal metastasis of gastric cancer, but an effective regimen to improve the dismal prognosis has not been developed yet.( 3 , 4 ) Previous reports have suggested that systemic perfusion of anticancer drugs has a limiting effect on peritoneal lesions due to the peritoneal‐plasma barrier, which prevent the effective drug delivery from blood into the peritoneal cavity.( 5 )

In comparison with systemic chemotherapy, intraperitoneal (i.p.) chemotherapy appears to have an advantage for peritoneal dissemination because the anticancer agents are directly delivered into the peritoneal cavity, which enables contact of a high concentration of drugs with tumor nodules. In i.p. chemotherapy, however, the limiting factor is the rapid clearance from the abdominal cavity of hydrophilic anticancer agents such as mytomicin‐C, cisplatin, and adriamicin.( 6 , 7 , 8 ) In contrast, paclitaxel (PTX), originally isolated from the tree Taxaus brevifolia,( 9 , 10 ) is slowly absorbed, and consequently retained in the peritoneal cavity for longer periods due to its high molecular weight and hydrophobicity,( 11 , 12 ) and it is thus supposed to be able to overcome this limitation. In fact, i.p. administration of PTX has been shown to have excellent clinical effects against ovarian cancer with peritoneal metastases.( 13 , 14 , 15 ) In addition, recent reports have also documented favorable outcomes of i.p. administration of PTX for peritoneal dissemination of gastric cancer.( 16 , 17 )

However, due to its low aqueous solubility, for clinical use, hydrophobic PTX has to be dissolved in Cremophor EL, a mixture of polyoxyethylated castor oil, and dehydrated ethanol. This solvent can sometimes cause serious side effects such as hypersensitivity reactions and neurotoxicity.( 18 , 19 ) In order to develop a safer and more effective method of administration, a variety of materials and delivery systems have been investigated as formulations for PTX.( 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ) Those studies have suggested that macromolecular PTX are retained for a long time in the blood stream and are favorably extravasated from vessels into the interstitium of tumor tissue due to their enhanced permeability and retention (EPR effect).( 26 , 27 ) On i.p. usage, however, the effect of such alternative formulations on antitumor activity against peritoneal tumors has not been well evaluated, although a few studies have suggested the advantage of macromolecular anticancer agents such as doxorubicin and zinostatin stimalamer (SMANCS®).( 28 , 29 ) In this study, therefore, we investigated the therapeutic effect of the micelle type–PTX after i.p. administration for peritoneal metastasis of gastric cancer.

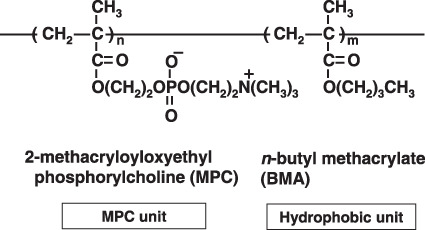

Here, we used a water‐soluble and amphiphilic polymer composed of 2‐methacryloxyethyl phosphorylcholine (MPC) and n‐butyl methacrylate (BMA) (PMB30W) (Fig. 1). The PMB30W has 70 mol% of the hydrophobic BMA unit, but water‐soluble. The characteristics of this co‐polymer are to form micelles when it is dissolved in aqueous media, and provide hydrophobic domains in aqueous media, and thus PMB30W is used clinically as a potential biomaterial for clinical applications because of its biocompatibility and hematocompatibility.( 30 ) PMB30W can dissolve 1000‐fold better than water and constructs nanoparticles containing PTX approximately 50 nm in diameter.( 31 , 32 ) The polymer having MPC units have been researched worldwide and they are well‐known biocompatible materials with high biocompatibility and blood compatibility. They have been applied as surface modification on various medical devices. Thus, the PMB30W also possesses excellent biocompatibility even in aqueous media. In fact, the safety of PTX solubulized with PMB30W (PTX‐30W) have been shown in our preliminary study.( 33 ) However, the in vivo antitumor effect of drugs using this material has not yet been determined. In this study, therefore, we evaluated the clinical efficacy of i.p. treatment using PTX‐30W solubulized with PMB30W for peritoneal dissemination in a mouse model.

Figure 1.

. The chemical structure of PMB‐30W, a co‐polymer of 2‐methacryloxyethyl phosphorylcholineand n‐butyl methacrylate. [Correction added after publication 13 July 2009.  was corrected to CH2 and N was corrected to N+].

was corrected to CH2 and N was corrected to N+].

Materials and Methods

Materials. PTX was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). Oregon green–conjugated 488 PTX (OG‐PTX) and a secondary antibody labeled with Alexa Fluors 594 were purchased from Molecular Probes (Portland, OR, USA). Rat monoclonal antibody to mouse platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (PECAM‐1) and DAPI were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA, USA) and Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka Japan), respectively.

Preparation of PTX‐formulation: PTX‐PBM‐30 complex. The PMB30W was synthesized by the conventional polymerization technique.( 32 , 34 ) The weight‐averaged molecular weight of the polymer was determined to be approximately 5.0 × 104. Fifty mg PMB30W was dissolved in 10 mL distilled water to make a 5.0% solution. Fifty mg of PTX were dissolved in 1.0 mL ethanol. The PTX solution (1 mL) and the PMB30W aqueous solution (10 mL) were mixed in a sample tube and filtered off using a micropore filter 0.22 µm pore in diameter. Then, the ethanol was removed under reduced pressure. An aliquot of the polymer solution was taken to measure the peak area of PTX by HPLC with a UV detector. For the Cremophor EL formulation, PTX was dissolved in Cremophor EL:ethanol (1:1, v/v) at a concentration of 6 mg/mL and used following dilution with PBS.

Cell culture. A human gastric cancer variant line, MKN45P, established from gastric cancer disseminated to the peritoneal cavity( 35 ) was routinely cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Sigma). After achieving subconfluence, the cells were removed by treatment with EDTA and trypsin, and used for experiments.

MTS assay for determination of cell proliferation. To examine the effect on in vitro growth of MKN‐45P, PTX was dissolved in Cremophor EL:ethanol (1:1, v/v) or 5% PMB30W, which were used for the cell proliferation assay. The concentration of vehicle in the medium was less than 0.1%. MKN45P (2 × 103 cells in 100 µl/well) were seeded into a 96‐well microtiter plate in DMEM containing 5% FBS. Cells were cultured overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2 to allow attachment. The medium was then aspirated and fresh medium containing 5% FBS and varying concentrations of PTX‐Cre and PTX‐30W was added to five replicate wells. After incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2 for the indicated periods, the number of living cells was measured using an MTS assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The number of living cells was then determined by measuring the absorbance at 490 nm.

Animal model of peritoneal dissemination. Four‐week‐old specific‐pathogen‐free conditioned female BALB/c nude mice were purchased from Charles River Japan (Yokohama, Japan), and housed in an air‐conditioned (23°C) light/dark (12 h) cycled room. At 5 weeks after birth, the mice were i.p. inoculated with 3.0 × 106 MKN45P cells suspended in 1 mL PBS. The mice were randomly divided into five groups (PBS, Cremophor EL, PMB30W, PTX‐Cre, PTX‐30W). Cremophor EL and PMB30W, the vehicle of PTX, were administered as control group (n = 8 for each group). On days 7, 14, and 21 after inoculation of MKN45P cells, the mice were treated with i.p. administration of the respective drugs. The total amount of injected liquid was set to 1.0 mL to optimize spreading of the administered drugs throughout the whole peritoneal cavity. The dose of PTX in each mouse was fixed at 20 µg/g body weight. On day 28 after inoculation, all mice were sacrificed and laparotomy was performed. The number of peritoneal nodules that had grown to over 1.0 mm in diameter was counted and the total weight of the combined nodules was measured. Body weight changes were also monitored as a toxic effect. Using the same methods of treatment, the survival of mice was also evaluated in each group up to day 60 (n = 10). All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for Animal Experiments of the University of Tokyo, and the protocols were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the University of Tokyo.

Measurement of concentration of PTX in peritoneal nodules. Female BALB/c nude mice were inoculated with MKN45P cells into the peritoneal cavity, as described above. On day 21 after inoculation, mice were allocated to two groups, the PTX‐Cre and PTX‐30W groups (n = 15 in each), and received i.p. administration of drugs. The same as for the experiment above, the dosage of PTX was fixed at 20 µg/g body weight and the total volume of liquid at 1 mL. At 3, 12, and 24 h after injection, five mice were sacrificed at each time‐point and the peritoneal nodules were removed from the abdominal cavity. After washing in 50 mL PBS three times to remove the PTX attached at the surface tissue, the nodules were frozen at –20°C until analysis.

Paclitaxel (PTX) concentration in nodules was measured using a HPLC procedure as described previously.( 36 ) The samples were processed after drying surface moisture, accurately weighed (0.1–2.0 g), and homogenized in 1–2 mL phosphoric acid. The homogenate was centrifuged at 24 000 g for 5 min and the supernatant was recovered as a sample. In brief, each sample (500 µL) was treated with 5 mL n‐butyl chloride and 100 µL n‐hexyl 4‐hydroxybenzoate as an internal standard. The sample was mixed thoroughly with vortex mixer. After centrifugation, the organic layer was discarded and remaining aqueous layer was used for analysis with the HPLC system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) using an ODS column (L‐column 4.6 × 250 mm; Chemicals Evaluation and Research Institute, Tokyo, Japan), of which the column temperature was maintained at 50°C. The mobile phase was 30:70 (phosphoric acid: methanol) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The effluent was detected at 227 nm and the peak was used for quantification.

Distribution of PTX in peritoneal nodules as determined by fluorescence microscopy. Peritoneal metastases were produced as described above. On day 21 after inoculation, Oregon green 488 PTX (OG‐PTX) dissolved in Cremophor EL:ethanol (1:1, v/v) or PMB30W was administered i.p. or i.v. Total volume of liquid administrated was fixed at 1 mL for the i.p. route, and the dosage of PTX was fixed at 5 µg/g body weight in each group. After 3, 12, and 24 h, the peritoneal nodules were excised, fixed for 1 h in 110% formalin in neutral buffer at room temperature, washed overnight in PBS containing 10% sucrose at 4°C, embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Tissue‐Tek; Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA, USA), and snap frozen in dry‐iced acetone for immunohistochemical examination.

The 10‐µm cryostat sections of postfixed frozen samples were examined for green fluorescein of OR‐PTX using a fluorescence stereomicroscope (BZ8000; Keyence, Osaka, Japan). The same sections were immunostained with a rat monoclonal antibody to mouse PECAM‐1 (1:200 dilution) (BD Pharmingen) to detect blood vessels. Subsequently, specimens were incubated with corresponding secondary antibodies labeled with Alexa Fluors 594 at 1:200 dilution. Cell nuclei were also counterstained with DAPI under a fluorescence microscope. OGP‐PTX, PECAM‐1, and DAPI were imaged using a green, red, and blue filter, respectively

Statistical analyses. The results were statistically examined by paired Student's t‐test when appropriate. Survival was analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method. Results are given as mean ± SD, and differences with P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

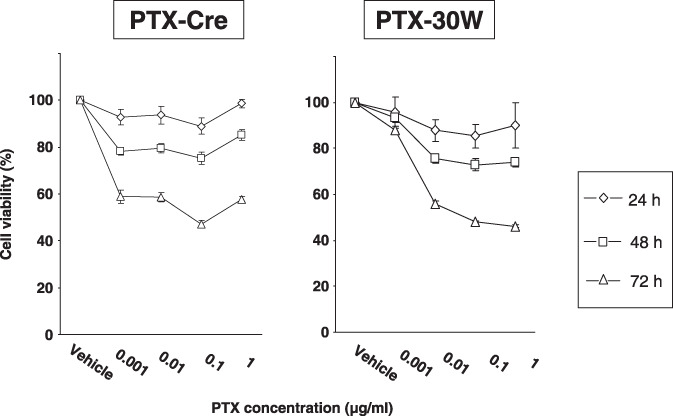

Cytotoxic activity of PTX‐30W and PTX‐Cre in vitro. We examined the direct effect of PTX solubulized with Cremophor EL (PTX‐Cre) or PMB30W (PTX‐30W) on the proliferation of MKN45P in vitro. As shown in Figure 2, the proliferative activity of MKN45P was similarly decreased by the addition of both PTX formulations in a dose‐ and time‐dependent manner. IC50 of PTX‐30W was similar to that of PTX‐Cre at 72 h (PTX‐30W, 0.060 µg/mL; PTX‐Cre, 0.054 µg/mL).

Figure 2.

In vitro cytotoxic effect of paclitaxel (PTX)‐Cre and PTX‐30W. MKN45P cells were seeded in 96‐well cell‐culture plates overnight before exposure to PTX‐Cre and PTX‐30W in a concentration range spanning 0.001 µg/mL to 1 µg/mL. Incubation was continued for 24, 48, or 72 h before MTS staining. Survival of treated cells compared to non‐treated controls at each time point is shown. Data show mean ± SD in three different experiments. *P < 0.05.

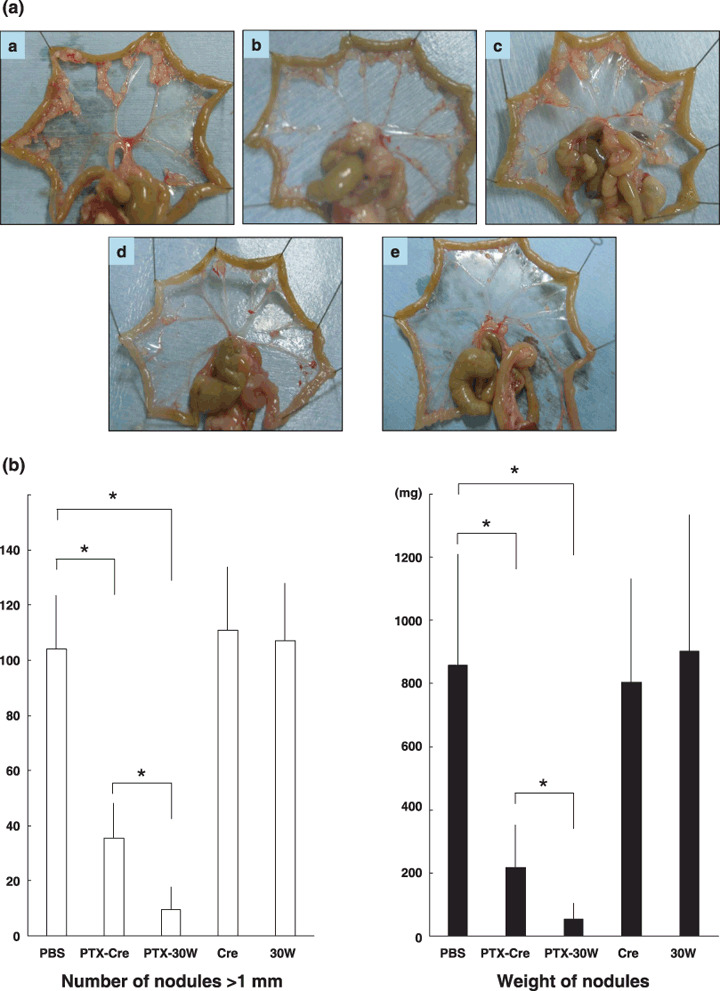

In vivo antitumor effect of PTX‐30W and PTX‐Cre. On day 28 after inoculation of MKN45P, all the mice that received thrice weekly consecutive chemotherapy were alive. However, the appearance of the mesentery showed a clear difference between the control groups (PBS, Cremophor EL, and PMB30W) and the treatment groups (PTX‐Cre and PTX‐30W) (Fig. 3a). The number of metastatic nodules over 1 mm and the total weight of the metastatic nodules were significantly reduced in the groups receiving PTX‐Cre as compared with the control groups. However, the growth inhibition of peritoneal metastases was far greater in the PTX‐30W group (Fig. 3a,b). The number and weight of metastatic nodules were reduced significantly more in mice receiving PTX‐30W than in the PTX‐Cre group (number: 9.6 ± 8.3 vs 35.5 ± 12.46, P < 0.05, weight: 218.8 ± 133.5 mg vs 55.0 ± 50.2 mg, P < 0.05) (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

In vivo antitumor effect of paclitaxel (PTX)‐Cre and PTX‐30W. (a) Representative photos of peritoneal nodules in each group. Many peritoneal metastatic nodules are observed in the PBS control (a), Cremophol EL (b), and PMB30W (c) groups. In the PTX‐Cre treatment group (d), the number of metastatic nodules on the peritoneum is decreased compared to that in the control groups. However, markedly fewer peritoneal metastases are present in mice treated with PTX‐30W (e). (b) Number of peritoneal metastatic nodules (>1 mm) (left) and total weight of tumors (right) in each group. PTX‐Cre significantly suppressed the development of peritoneal metastases. However, PTX‐30W significantly reduced the number and tumor volume compared to PTX‐Cre (*P < 0.05). Data show mean ± SD in eight mice.

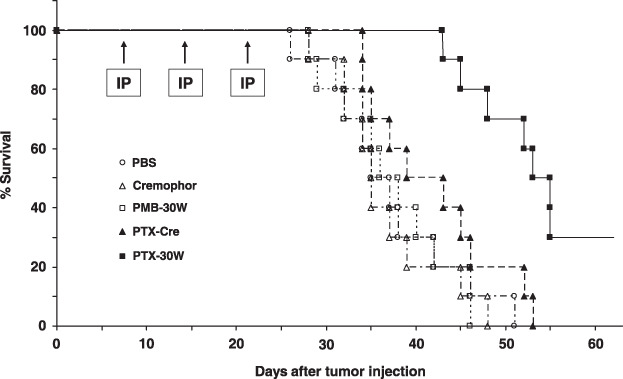

Moreover, when the survival of treated mice was compared with that of control mice, the median survival of the PTX‐Cre group was not different from that of control mice, whereas mice receiving PTX‐30W showed significantly prolonged survival (P < 0.05 vs all other groups) (Fig. 4). These data clearly indicate that i.p. administration of PTX nanoparticles was more effective in suppressing the growth of peritoneal metastases than the conventional PTX drug.

Figure 4.

Survival of mice treated with paclitaxel (PTX)‐Cre or PTX‐30W. Kaplan–Meier analysis of survival of mice that received i.p. injection of PBS ( ), Cremophor EL (

), Cremophor EL ( ), PMB30W (

), PMB30W ( ), PTX‐Cre (

), PTX‐Cre ( ), or PTX‐30W (

), or PTX‐30W ( ) once a week for 3 consecutive weeks. Median survival was prolonged in the PTX‐30W (51.8 days) as compared with the PTX‐Cre group (41.8 days) (P < 0.05).

) once a week for 3 consecutive weeks. Median survival was prolonged in the PTX‐30W (51.8 days) as compared with the PTX‐Cre group (41.8 days) (P < 0.05).

Paclitaxel (PTX) concentration in peritoneal nodules after i.p. injection. Next, we examined the concentration of PTX in tumor nodules disseminated on the peritoneal surface. As shown in Table 1, the PTX concentration in peritoneal tumors in mice receiving PTX‐30W was significantly higher than that in mice receiving PTX‐Cre, at all time‐points (P < 0.05). This suggests that the polymeric micelle carrier PMB30W enhances the retention of i.p.‐injected PTX in metastatic nodules as compared to Cremophor EL.

Table 1.

Paclitaxel (PTX) concentration in metastatic peritoneal nodules

| Time after i.p. injection | PTX‐Cre | PTX‐30W | P‐values |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 h | 4525 ± 612 | 8256 ± 912 | <0.05 |

| 12 h | 1173 ± 83 | 2011 ± 674 | <0.05 |

| 24 h | 882 ± 149 | 1137 ± 291 | <0.05 |

| (ng/gr, tumor) | |||

The nodules excised from peritoneum of each mouse were homogenized, and concentration of PTX in the supernatant after the centrifugation of the homogenate solution was measured with HPLC. The intratumoral concentrations of PTX calculated were significantly higher in the group of mice receiving the PTX‐30W as compared with PTX‐Cre at all time‐points (*P < 0.05). Data show the mean ± SD.

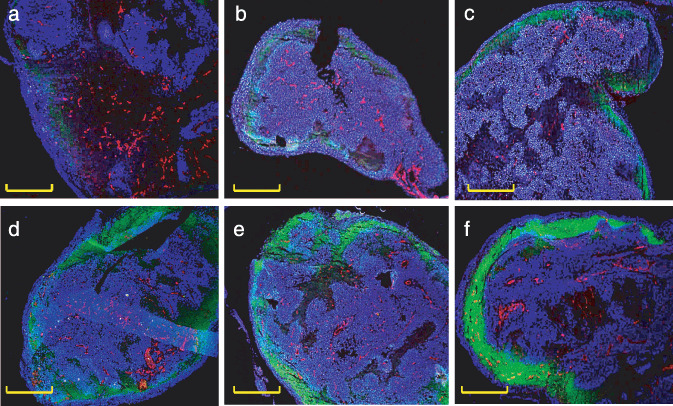

Distribution of i.p.‐injected PTX in peritoneal nodules. To examine the topical distribution of PTX‐Cre and PTX‐30W in metastatic nodules in the peritoneal cavity, Oregon green–conjugated PTX (OG‐PTX) diluted in Cremophor EL or PMB30W solution was injected into the peritoneal cavity of mice developing peritoneal metastases. In both groups, green fluorescence was observed in the peripheral area of tumor tissue, suggesting that PTX infiltrates from the surface of peritoneal nodules (Fig. 5). However, the fluorescent intensity was obviously stronger in the PTX‐30W group than in the PTX‐Cre group at all time‐points. As shown in Figure 6a–c, the fluorescent signal of OG‐PTX formulated with Cremophor EL was detected at 12–24 h after injection and was restricted to the peripheral area up to 100–200 µm deep to the tumor surface. In comparison, the signal of OG‐PTX with PMB30W was already clearly detected at 3 h after injection, and the depth of infiltration reached up to several hundred µm from the tumor surface at 12–24 h after injection (Fig. 6d–f). This clearly indicates that PTX‐30W infiltrates tumor tissue more efficiently than PTX‐Cre.

Figure 5.

Spacial distribution of paclitaxel (PTX)‐Cre or PTX‐30W in disseminated tumors after i.p. injection. Peritoneal nodules around 3 mm in diameter were excised at 3 (a,d), 12 (b,d), and 24 (c,f) h after i.p. injection of Oregon green–conjugated 488 PTX (OG‐PTX) diluted in Cremophor EL (a–c) or PMB30W (d–f). The intratumorous distribution pattern of PTX in the peritoneal nodules are shown in representative three color composite images showing the distribution of PTX (green), CD31‐positive blood vessels (red), and nuclei (blue). PTX demonstrated by green fluorescence was highly detected in the peripheral area of tumor tissue. However, fluorescent intensity was significantly stronger for OG‐PTX diluted in PMB30W (d–f) as compared with that in Cremophor EL (a–c) at all time‐points. Yellow scale bars indicate 1 mm.

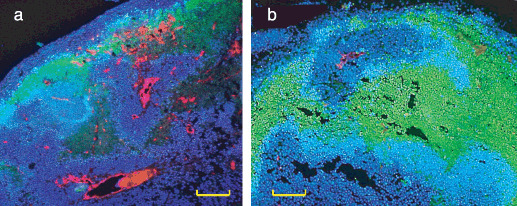

Figure 6.

Paclitaxel (PTX)‐30W does not evenly penetrate into disseminated nodules. At 3 (a) and 24 (b) h after i.p. injection of Oregon green–conjugated 488 PTX (OG‐PTX) formulated with PMB30W, green fluorescence of OG‐PTX was highly observed in relatively hypovascular areas, but was not detected in perivascular areas. Red and blue indicate CD31‐positive blood vessels and nuclei, respectively. Yellow scale bars indicate 200 µm.

Interestingly, i.p.‐administered OG‐PTX formulated with PMB30W did not evenly infiltrate into tumor tissue. At 3 h after i.p. injection, OG‐PTX appeared to preferentially infiltrate into the DAPI‐weak area (Fig. 6a). Moreover, at 24 h after injection, green fluorescence was strong in the deeper area, whereas it was not detected in the DAPI‐positive site around CD31‐positive tumor vessels even in the tumor periphery (Fig. 6b). This suggests that i.p.‐administered PTX‐30W may preferentially accumulate in relatively hypovascular areas in disseminated nodules.

Discussion

Recent studies on new drug delivery systems have demonstrated that anticancer agents incorporated in polymeric micelle carrier accumulate preferentially in tumor tissue and reduce nonspecific accumulation in normal tissue due to their nanoscale size and stability, which is known as the enhanced permeation and retention (EPR) effect.( 26 , 27 ) However, the kinetics of such drug‐incorporating nanomicelles after i.p. administration have not been well examined. Previous studies have indicated that carriers with large molecular weight mainly drained from the peritoneal cavity through the lymphatic duct, and their clearance was relatively slow.( 37 , 38 , 39 ) In fact, Lu et al. have recently shown that PTX nanoparticles synthesized with an ultrasonic emulsion using polyvinyl alcohol were highly localized in lymph nodes as well as intra‐abdominal tumors.( 40 )

The PMB30W has been shown to take polymer aggregate with a sphere shape of 23 nm in diameter in aqueous medium using light‐scattering measurement,( 31 ) and thus could be used as a carrier of PTX in our experiments. In fact, the aggregate containing PTX provides highly water‐soluble formulation with 50 nm in diameter and the outer MPC units diminish nonspecific capture by the reticuloendothelial system.( 32 ) Therefore, we hypothesized that PTX formulated with PMB30W (PTX‐30W) could avoid uptake by peritoneal macrophages and thus achieve a longer half‐life in the peritoneal cavity, which would permit a large amount of the drug‐incorporated micelles to reach disseminated tumors in the peritoneal cavity.

In the present study, we found that i.p.‐administered PTX‐30W significantly inhibited the growth of peritoneal metastases of gastric cancer and prolonged survival as compared to PTX‐Cre in vivo, although IC50 of PTX‐30W was similar to that of PTX‐Cre in vitro. Moreover, PTX concentration in peritoneal nodules measured by the HPLC method was significantly higher in the PTX‐30W than in the PTX‐Cre group up to 24 h after i.p. injection. Since this method may not accurately reflect the real concentration of PTX in tumor tissue, we also evaluated the intratumorous special distribution of PTX by fluorescence microscopicic observation. In this series of experiments, we determined that the OG‐PTX highly accumulated in the peripheral area of disseminated tumor tissue up to 24 h after i.p. administration. Moreover, the fluorescent intensity of OG‐PTX in tumor sites was markedly stronger in the PMB30W‐solubulized form as compared with the Cremophpr EL‐solubulized form at every time‐point, which was mostly consistent with the HPLC results. These findings are basically consistent with the results of Lu et al.( 40 ) and suggest that the superior inhibitory effect of PTX‐30W on peritoneal dissemination is attributable to the distinct pharmacokinetic characteristics of PTX‐30W after i.p. administration. The fluorescent results also suggests that the preferential accumulation of PTX‐30W in disseminated tumor may be attributable not only to the sustained release of PTX from PTX‐30W or EPR effects, but also to the superior capacity of PTX‐30W to penetrate directly into peritoneal nodules.

An interesting finding in our fluorescent study is that OG‐PTX tended to be detected strongly in relatively hypovascular areas in peripheral tumor sites. This was a marked contrast to the results of other studies which demonstrated preferential accumulation of anticancer drugs in perivascular areas in tumor tissue after intravenous administration.( 41 , 42 ) In fact, when we injected OG‐PTX intravenously in tumor‐bearing mice, slight green fluorescence was observed around tumor vessels in peritoneal nodules at an early time‐point (data not shown). The exact mechanism of the preferential accumulation in hypovascular areas after i.p. injection is as yet unclear. However, many factors such as the size, charge, and water solubility of drugs are known to be related to the distribution and diffusion of anticancer agents in solid tumors.( 43 ) Moreover, drug penetration has been reported to be impeded by severe fibrosis and high interstitial pressure.( 44 , 45 ) These physicochemical factors are considered to be involved in this drug distribution. Although still preliminary, our results may suggest the possibility that i.p.‐administered drugs can be highly delivered even in tumors with low vascularity.

The limited access of the anticancer agent into the deeper interior from the cavitary compartment is probably the most important problem in regional anticancer therapy. Previous reports of ovarian cancer have suggested that i.p. chemotherapy is not so beneficial in bulky tumors because of limited drug penetration.( 46 , 47 ) Several studies have reported that penetration of PTX into tissue was also limited, as for other cancer agents. Moreover, Cremophor EL, the vehicle used for PTX, has been shown to reduce free PTX drug available for diffusion.( 12 , 48 , 49 ) In contrast, a previous report has suggested that a polymeric micelle carrier could infiltrate deeply into an avascular tumor model, multicellular tumor spheroids.( 50 ) These results are thought to be consistent with ours in that PTX‐30W could highly accumulate in disseminated tumor tissue after i.p. injection.

In summary, we demonstrated that i.p. administration of PTX‐30W can elicit much stronger antitumor effects on peritoneal metastasis than conventional PTX formulated in Cremophor, presumably because of its characteristic to accumulate more preferentially in disseminated nodules. The biocompatibility and safety of PMB30W, when injected into the bloodstream, have already been verified by animal experiments.( 32 , 33 ) PTX‐30W may be highly suitable for i.p. administration and thus could be a promising anticancer agent for peritoneal carcinomatosis. This nano‐drug warrants clinical evaluation in this dismal condition.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chieko Uchikawa, Kahoru Amitani, and Junko Kawakita for their excellent technical assistance. This study was funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, and the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan.

References

- 1. Yoo CH, Noh SH, Shin DW, Choi SH, Min JS. Recurrence following curative resection for gastric carcinoma. Br J Surg 2000; 87: 236–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chu DZ, Lang NP, Thompson C, Osteen PK, Westbrook KC. Peritoneal carcinomatosis in nongynecologic malignancy. A prospective study of prognostic factors. Cancer 1989; 63: 364–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brigand C, Arvieux C, Gilly FN, Glehen O. Treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis in gastric cancers. Dig Dis 2004; 22: 366–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tetzlaff ED, Cen P, Ajani JA. Emerging drugs in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2008; 13: 135–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jacquet P, Sugarbaker PH. Peritoneal‐plasma barrier. Cancer Treat Res 1996; 82: 53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hagiwara A, Togawa T, Yamasaki J et al . Extensive gastrectomy and carbon‐adsorbed mitomycin C for gastric cancer with peritoneal metastases. Case reports of survivors and their implications. Hepatogastroenterology 1999; 46: 1673–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hagiwara A, Takahashi T, Sawai K et al . Clinical trials with intraperitoneal cisplatin microspheres for malignant ascites – a pilot study. Anticancer Drug Des 1993; 8: 463–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Demicheli R, Bonciarelli G, Jirillo A et al . Pharmacologic data and technical feasibility of intraperitoneal doxorubicin administration. Tumori 1985; 71: 63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wani MC, Taylor HL, Wall ME, Coggon P, McPhail AT. Plant antitumor agents. VI. The isolation and structure of taxol, a novel antileukemic and antitumor agent from Taxus brevifolia. J Am Chem Soc 1971; 93: 2325–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rowinsky EK, Cazenave LA, Donehower RC. Taxol: a novel investigational antimicrotubule agent. J Natl Cancer Inst 1990; 82: 1247–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eiseman JL, Eddington ND, Leslie J et al . Plasma pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of paclitaxel in CD2F1 mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1994; 34: 465–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gelderblom H, Verweij J, Van Zomeren DM et al . Influence of Cremophor El on the bioavailability of intraperitoneal paclitaxel. Clin Cancer Res 2002; 8: 1237–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Armstrong DK, Bundy B, Wenzel L et al . Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 34–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Markman M, Bundy BN, Alberts DS et al . Phase III trial of standard‐dose intravenous cisplatin plus paclitaxel versus moderately high‐dose carboplatin followed by intravenous paclitaxel and intraperitoneal cisplatin in small‐volume stage III ovarian carcinoma: an intergroup study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group, Southwestern Oncology Group, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 1001–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Bree E, Rosing H, Michalakis J et al . Intraperitoneal chemotherapy with taxanes for ovarian cancer with peritoneal dissemination. Eur J Surg Oncol 2006; 32: 666–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kodera Y, Ito Y, Ito S et al . Intraperitoneal paclitaxel: a possible impact of regional delivery for prevention of peritoneal carcinomatosis in patients with gastric carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology 2007; 54: 960–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tamura S, Miki H, Okada K et al . Pilot study of intraperitoneal administration of paclitaxel and oral S‐1 for patients with peritoneal metastasis due to advanced gastric cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 2008; 13: 536–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weiss RB, Donehower RC, Wiernik PH et al . Hypersensitivity reactions from taxol. J Clin Oncol 1990; 8: 1263–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lorenz W, Reimann HJ, Schmal A et al . Histamine release in dogs by Cremophor E1 and its derivatives: oxethylated oleic acid is the most effective constituent. Agents Actions 1977; 7: 63–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Auzenne E, Donato NJ, Li C et al . Superior therapeutic profile of poly‐L‐glutamic acid‐paclitaxel copolymer compared with taxol in xenogeneic compartmental models of human ovarian carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2002; 8: 573–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sharma A, Mayhew E, Bolcsak L et al . Activity of paclitaxel liposome formulations against human ovarian tumor xenografts. Int J Cancer 1997; 71: 103–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Merisko‐Liversidge E, Sarpotdar P, Bruno J et al . Formulation and antitumor activity evaluation of nanocrystalline suspensions of poorly soluble anticancer drugs. Pharm Res 1996; 13: 272–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gradishar WJ, Tjulandin S, Davidson N et al . Phase III trial of nanoparticle albumin‐bound paclitaxel compared with polyethylated castor oil‐based paclitaxel in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 7794–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Micha JP, Goldstein BH, Birk CL, Rettenmaier MA, Brown JV 3rd. Abraxane in the treatment of ovarian cancer: the absence of hypersensitivity reactions. Gynecol Oncol 2006; 100: 437–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hamaguchi T, Matsumura Y, Suzuki M et al . NK105, a paclitaxel‐incorporating micellar nanoparticle formulation, can extend in vivo antitumour activity and reduce the neurotoxicity of paclitaxel. Br J Cancer 2005; 92: 1240–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Matsumura Y, Maeda H. A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs. Cancer Res 1986; 46(12 Pt 1): 6387–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maeda H, Wu J, Sawa T, Matsumura Y, Hori K. Tumor vascular permeability and the EPR effect in macromolecular therapeutics: a review. J Control Release 2000; 65: 271–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kimura M, Konno T, Oda T, Maeda H, Miyauchi Y. Intracavitary treatment of malignant ascitic carcinomatosis with oily anticancer agents in rats. Anticancer Res 1993; 13: 1287–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kimura M, Konno T, Miyamoto Y, Kojima Y, Maeda H. Intracavitary administration: pharmacokinetic advantages of macromolecular anticancer agents against peritoneal and pleural carcinomatoses. Anticancer Res 1998; 18: 2547–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ishihara K, Ziats NP, Tierney BP, Nakabayashi N, Anderson JM. Protein adsorption from human plasma is reduced on phospholipid polymers. J Biomed Mater Res 1991; 25: 1397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ishihara K, Iwasaki Y, Nakabayashi N. Polymeric lipid nanosphere consisting of water‐soluble poly (2‐methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine‐co‐n‐butyl methacrylate). Polym J 1999; 31: 1231–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Konno T, Watanabe J, Ishihara K. Enhanced solubility of paclitaxel using water‐soluble and biocompatible 2‐methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine polymers. J Biomed Mater Res A 2003; 65: 209–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wada M, Jinno H, Ueda M et al . Efficacy of an MPC‐BMA co‐polymer as a nanotransporter for paclitaxel. Anticancer Res 2007; 27: 1431–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ishihara K, Ueda T, Nakabayashi N. Preparation of phospholipid polymers and their properties as polymer hydrogel membrane. Polym J 1990; 22: 355–60. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sako A, Kitayama J, Koyama H et al . Transduction of soluble Flt‐1 gene to peritoneal mesothelial cells can effectively suppress peritoneal metastasis of gastric cancer. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 3624–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee SH, Yoo SD, Lee KH. Rapid and sensitive determination of paclitaxel in mouse plasma by high‐performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl 1999; 724: 357–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shih WJ, Coupal JJ, Chia HL. Communication between peritoneal cavity and mediastinal lymph nodes demonstrated by Tc‐99m albumin nanocolloid intraperitoneal injection. Proc Natl Sci Counc Repub China B 1993; 17: 103–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mohamed F, Sugarbaker PH. Carrier solutions for intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2003; 12: 813–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kohane DS, Tse JY, Yeo Y, Padera R, Shubina M, Langer R. Biodegradable polymeric microspheres and nanospheres for drug delivery in the peritoneum. J Biomed Mater Res A 2006; 77: 351–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lu H, Li B, Kang Y et al . Paclitaxel nanoparticle inhibits growth of ovarian cancer xenografts and enhances lymphatic targeting. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2007; 59: 175–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lankelma J, Dekker H, Luque FR et al . Doxorubicin gradients in human breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 1999; 5: 1703–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Primeau AJ, Rendon A, Hedley D, Lilge L, Tannock IF. The distribution of the anticancer drug Doxorubicin in relation to blood vessels in solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11(24 Pt 1): 8782–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Minchinton AI, Tannock IF. Drug penetration in solid tumours. Nat Rev Cancer 2006; 6: 583–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yashiro M, Chung YS, Nishimura S, Inoue T, Sowa M. Fibrosis in the peritoneum induced by scirrhous gastric cancer cells may act as ‘soil’ for peritoneal dissemination. Cancer 1996; 77(8 Suppl): 1668–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jain RK. Barriers to drug delivery in solid tumors. Sci Am 1994; 271: 58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Carney ME, Lancaster JM, Ford C, Tsodikov A, Wiggins CL. A population‐based study of patterns of care for ovarian cancer: who is seen by a gynecologic oncologist and who is not? Gynecol Oncol 2002; 84: 36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bristow RE, Zahurak ML, Del Carmen MG et al . Ovarian cancer surgery in Maryland: volume‐based access to care. Gynecol Oncol 2004; 93: 353–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ten Tije AJ, Verweij J, Loos WJ, Sparreboom A. Pharmacological effects of formulation vehicles: implications for cancer chemotherapy. Clin Pharmacokinet 2003; 42: 665–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Knemeyer I, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Cremophor reduces paclitaxel penetration into bladder wall during intravesical treatment. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1999; 44: 241–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bae Y, Nishiyama N, Fukushima S, Koyama H, Yasuhiro M, Kataoka K. Preparation and biological characterization of polymeric micelle drug carriers with intracellular pH‐triggered drug release property: tumor permeability, controlled subcellular drug distribution, and enhanced in vivo antitumor efficacy. Bioconjug Chem 2005; 16: 122–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]