Abstract

Retrovirus assembly involves a complex series of events in which a large number of proteins must be targeted to a point on the plasma membrane where immature viruses bud from the cell. Gag polyproteins of most retroviruses assemble an immature capsid on the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane during the budding process (C-type assembly), but a few assemble immature capsids deep in the cytoplasm and are then transported to the plasma membrane (B- or D-type assembly), where they are enveloped. With both assembly phenotypes, Gag polyproteins must be transported to the site of viral budding in either a relatively unassembled form (C type) or a completely assembled form (B and D types). The molecular nature of this transport process and the host cell factors that are involved have remained obscure. During the development of a recombinant baculovirus/insect cell system for the expression of both C-type and D-type Gag polyproteins, we discovered an insect cell line (High Five) with two distinct defects that resulted in the reduced release of virus-like particles. The first of these was a pronounced defect in the transport of D-type but not C-type Gag polyproteins to the plasma membrane. High Five cells expressing wild-type Mason-Pfizer monkey virus (M-PMV) Gag precursors accumulate assembled immature capsids in large cytoplasmic aggregates similar to a transport-defective mutant (MA-A18V). In contrast, a larger fraction of the Gag molecules encoded by the M-PMV C-type morphogenesis mutant (MA-R55W) and those of human immunodeficiency virus were transported to the plasma membrane for assembly and budding of virions. When pulse-labeled Gag precursors from High Five cells were fractionated on velocity gradients, they sedimented more rapidly, indicating that they are sequestered in a higher-molecular-mass complex. Compared to Sf9 insect cells, the High Five cells also demonstrate a defect in the release of C-type virus particles. These findings support the hypothesis that host cell factors are important in the process of Gag transport and in the release of enveloped viral particles.

The assembly of an infectious retrovirus requires the coordinated expression of a minimum of three open reading frames found within all retroviral genomes: gag, pol, and env (55). Retrovirus capsid assembly is directed by the gag gene product, and expression of the gag gene product alone is sufficient for retroviral immature capsid assembly in the cytoplasm, followed by the budding and release of enveloped virus-like particles (VLPs) from the plasma membrane (10, 17, 22, 23, 28, 39, 44, 48, 59). Retroviral Gag polyproteins, the product of gag gene expression, are synthesized in the cytoplasm and self-associate with one another by undefined molecular mechanisms to form a spherical immature capsid containing genomic RNA. The Gag polyproteins contain a series of basic amino acids near the amino terminus, and most are modified by cotranslational amino-terminal myristoylation, promoting an association with cell membranes (21). In most retroviruses, Gag polyproteins interact specifically with the plasma membrane to initiate the viral budding process, culminating in the release of an extracellular immature VLP (reviewed in reference 25). During or immediately following viral budding, the Gag polyproteins are cleaved by a viral proteinase into the structural proteins that constitute a mature infectious virion, and the spherical immature capsid condenses to form an asymmetric mature viral core (reviewed in reference 56). In all retroviruses, these mature structural proteins include the matrix protein associated with the viral membrane; the major capsid protein forming the asymmetric viral core; and the nucleocapsid protein associated with the viral genomic RNA within the core (26).

The differential timing and cellular location of Gag polyprotein assembly relative to the viral budding event separates retroviral morphogenesis into two types. For C-type retroviruses such as human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and Moloney murine leukemia virus, Gag polyproteins are transported as monomers or small oligomers to the plasma membrane, where capsid assembly begins and is completed coincident with the viral budding process (16). For B- and D-type retroviruses such as mouse mammary tumor virus and Mason-Pfizer monkey virus (M-PMV), respectively, immature capsids assemble to completion in the cytoplasm away from the plasma membrane (13). The assembled capsids must then migrate to the plasma membrane for budding and release. Despite these differences, there is evidence that the fundamental assembly mechanism of all retroviruses is the same: a single point mutation in the matrix protein of M-PMV (R55W) converts particle assembly from D-type to C-type morphogenesis (42). Thus, the differences in the assembly process of C-type and D-type retroviruses may only be a matter of Gag polyprotein targeting to an assembly site at the cellular membrane versus a site deeper in the cytoplasm of the cell. However, expression of Gag polyproteins in vitro demonstrates that while both C- and D-type Gag polyproteins can assemble in vitro (2, 3, 19, 51, 53), M-PMV Gag is a far more efficient substrate for an in vitro assembly reaction (45). Assembly away from cell membranes has been observed when C-type Gag polyproteins are overexpressed in insect cells (9, 44), but the efficient assembly of a C-type retrovirus may require an interaction with host cell membranes or membrane-associated factors.

Molecular genetic studies of C- and D-type retroviral gag genes indicate that the amino-terminal matrix domain is important in directing Gag polyproteins to the plasma membrane. The matrix domain resides at the periphery of the assembled or partially assembled immature capsid and is intimately associated with the cell membrane during and after the viral budding event (15, 36). Removal of the myristic acid or the polybasic region near the amino terminus attenuates HIV-1 Gag-membrane binding affinities and also interferes with the active transport of Gag polyproteins to the cell membrane (29, 32, 52, 62). Furthermore, alterations in the HIV-1 matrix domain can redirect Gag polyproteins to alternative sites (4, 12, 25). Similar studies of M-PMV, the prototype D-type retrovirus, also demonstrate that amino-terminal myristoylation is necessary to direct the Gag polyproteins, in the form of assembled capsids, to the plasma membrane (41). Deletions within the M-PMV matrix domain result in an unstable Gag polyprotein that is rapidly degraded, and the transport characteristics cannot be assessed (43). However, when point mutations such as A18V are introduced into the polybasic region of the matrix domain of M-PMV, the myristoylated and assembled capsids are not transported to the plasma membrane but instead accumulate in the cytoplasm at their site of assembly (40).

Since C-type assembly is rarely seen with the expression of wild-type M-PMV Gag, it is assumed that unassembled or partially assembled M-PMV Gag polyproteins are excluded from the cellular transport process that directs assembled capsids to the plasma membrane. Only after the completion of immature-capsid assembly is a matrix domain motif displayed for interaction with cellular transport elements. It has also been suggested that M-PMV Gag polyproteins contain a cytoplasmic targeting or retention signal (CTRS) that restricts transport to the plasma membrane until immature capsid assembly is complete (6, 42). However, the exclusion of unassembled M-PMV Gag polyproteins from the transport process can be overcome by the introduction of the R55W point mutation described above, which undergoes C-type viral budding at the plasma membrane. Thus, the R55W point mutation either must alter a membrane transport signal, such that it is active in the unassembled Gag polyprotein, or it must attenuate the function of a CTRS. Alternative explanations for the R55W phenotype include an alteration in assembly characteristics such that membranes are required for assembly or that cytoplasmic assembly is less efficient and free Gag monomers or small multimers are then available for transport to the plasma membrane. However, an in vitro analysis of M-PMV Gag R55W assembly shows that the altered matrix domain does not affect capsid formation in the absence of membranes and confirms that the C-type assembly process is due to an alteration in transport characteristics (46). Thus, for M-PMV, the assembly phenotype as a C-type versus D-type retrovirus depends only upon the functional activity of a CTRS and/or the ability of cellular transport machinery to recognize unassembled Gag polyproteins versus assembled immature capsids.

Although some of the C-type and D-type retroviral Gag polyprotein domains that affect transport to the plasma membrane have been characterized, the elements of the cellular transport machinery that interact with Gag polyproteins are not well understood. The expression of retroviral Gag polyproteins in a variety of eukaryotic cell lines, including insect cells, results in the assembly and release of extracellular VLPs with ultrastructural characteristics identical to those of virions produced from infected cell lines (9, 17, 49, 54, 60). The host cell factors necessary for Gag transport and the release of extracellular particles must then be well conserved. Host cell lines completely defective in the active transport of retroviral immature capsids or unassembled Gag polyproteins have not been described. Here we report on an insect cell line with a pronounced defect in the transport of D-type but not C-type Gag polyproteins to the plasma membrane.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid DNA constructs.

All recombinant DNA-cloning techniques followed established methods described elsewhere (47). Restriction and modification enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.). A portion of the M-PMV genome (50), containing the M-PMV gag, pro, and pol open reading frames, was removed from pSHRMX, a modification of the genomic clone, pSHRM15 (39), by using the HhaI site at nucleotide 486 and an XhoI site engineered into the genome at the end of the pol reading frame where nucleotides 5816 and 5817 (CT) were converted to TC. The HhaI site was blunt ended with Klenow fragment (New England BioLabs), and the genomic fragment was ligated with the pSP73 (Promega, Madison, Wis.) vector by using the EcoRI (blunt ended with Klenow fragment) and SalI sites to create plasmid pSP73GX. An SspI (pSP73 nucleotide 2012)-SphI (nucleotide 26) fragment from the pSP73 polylinker and flanking region was then ligated to the pSP73GX SphI and XhoI (blunt ended with Klenow fragment) sites to create pSP73GXS. The M-PMV sequence was then removed from pSP73GXS with EcoRI sites, blunt ended with Klenow fragment, and ligated with the pBacPAK1 baculovirus transfer vector (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) by using the BamHI site, blunt ended with Klenow fragment, to create pBKMGXS. The pBKMGXS vector was made with the wild-type M-PMV matrix domain, as well as A18V, R55W, and both A18V and R55W matrix point mutations. The viral proteinase was inactivated by a previously described point mutation (D26N) in the active site in all M-PMV gag-pro-pol expression vectors (49). The HIV-1 gag-pro-pol open reading frames were removed from a proviral clone (HXB2Dgpt) (14) by engineering an XbaI site near the gag initiation codon and then removing the sequence between the XbaI site and the NdeI site at nucleotide 5122. The NdeI site was blunt ended with Klenow fragment, and the gag-pro-pol sequence was ligated with vector pSP72 (Promega) by using the XbaI and Klenow fragment blunt-ended XhoI sites to create plasmid pSP72HXBgag. The gag-pro-pol sequence was removed from pSP72HXBgag with BamHI and NdeI (blunt ended with Klenow fragment) sites and ligated with the BamHI and StuI sites in the baculovirus transfer vector pBacPAK9 (Clontech) to create plasmid pBKHXBgag. The HIV-1 proteinase-active site was inactivated with a D25N point mutation as with the M-PMV gag transfer vectors.

Insect cell culture.

A sample of the Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) insect cell line was purchased from the American Tissue Type Collection. Sf9 cells were grown at 27°C in standard tissue culture flasks with supplemented Grace's medium (JRH Biosciences, Lenexa, Kans.) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). High Five (Trichoplusia ni) insect cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) were grown at 27°C in EX-CELL 405 medium from JRH without serum.

Generation of recombinant baculovirus.

Baculovirus plasmid transfer vectors and predigested baculovirus genomic DNA were purchased from Clontech (BacPAK system). Transfer vectors containing M-PMV or HIV-1 gag-pro-pol open reading frames were cotransfected with the predigested baculovirus genomic DNA into Sf9 cells with Lipofectin (Clontech) as specified by the manufacturer. Recombinant baculoviruses were purified by following a previously described protocol for end-point dilution assays and screened for M-PMV or HIV-1 Gag expression by Western blot analysis of cell lysates (30).

Western blot analysis of cell lysates and cell supernatants.

Sf9 and High Five cells were infected with recombinant baculovirus at a multiplicity of infection of 5. At 40 h after infection, the cells were lysed in protein gel-loading buffer (47) and the cell culture medium was centrifuged through a 35% (wt/vol) sucrose cushion in a Beckman TLA 100.3 rotor at 100,000 rpm for 30 min to pellet VLPs. The pellets were resuspended in protein gel-loading buffer. Then 2% of each cell lysate and VLP pellet was analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a Protran BA85 nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany). The blots were probed with M-PMV and HIV-1 Gag-specific antisera and horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies and then developed with SuperSignal chemiluminescent reagents (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

EM of infected insect cells.

At 48 h after infection at a multiplicity of infection of 5 with recombinant baculovirus expressing M-PMV or HIV-1 gag genes, Sf9 and High Five insect cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.1) and resuspended in 1% glutaraldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, Mo.) in PBS with 10 mg of tannic acid (Sigma) per ml for 1 h on ice. The fixed cells were then washed in PBS, resuspended in 2% osmium tetroxide in PBS with 5 mg of tannic acid per ml, and processed for electron microscopy (EM) as described previously (7).

Metabolic labeling of insect cells and analysis of cell lysates.

At 36 h after infection of 60-mm plates of Sf9 or High Five cells with recombinant baculovirus expressing M-PMV or HIV-1 gag genes, cells were washed and starved in methionine-free Grace's insect cell culture medium (Gibco BRL) for 30 min and then incubated for 30 min in 35S protein-labeling mix (EXPRE35S35S; NEN Life Science Products, Boston, Mass.) at 100 μCi/300 μl per plate. For pulse-labeling, the cells were then lysed on ice in 500 μl of capsid extraction buffer (1% [vol/vol] Triton X-100 [Sigma], 10 mM Tris [pH 7.6], 1 mM EDTA, 500 mM NaCl) for 30 min. For chase experiments, the cells were incubated for 14 h in complete growth medium following pulse-labeling and then lysed as above. Following cell lysis, the lysates were centrifuged in a refrigerated microcentrifuge for 3 min at 14,000 rpm and 4°C. The supernatant was loaded onto sucrose velocity gradients containing 5 to 20% (wt/vol) sucrose with 10 mM Tris (pH 7.6), 500 mM NaCl, and 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 in a Beckman SW41 tube. The gradients were centrifuged in a Beckman SW41 rotor at 25,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C, and 1-ml fractions were collected by hand from the top of the gradients. Each gradient fraction and the cell culture medium were immunoprecipitated with rabbit anti-M-PMV Pr78Gag or human anti HIV-1 polyclonal antisera and analyzed by SDS-PAGE as described previously (1). The M-PMV or HIV-1 Gag proteins were quantitated on the dried gels with a Storm 860 PhosphorImager and the data were analyzed by ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics Inc., Sunnyvale, Calif.).

Transient proviral gene expression in mammalian cells.

Human 293T cells (11) were grown at 37°C under 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco). The cells were transfected by M-PMV proviral plasmid DNA (pSHRM15 [described above]) by previously described techniques (5). At 36 h after transfection, the cells were incubated in methionine-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Sigma) for 30 min and then pulse-labeled for 30 min with 250 μCi of 35S protein-labeling mix in 200 μl of methionine-free medium. After pulse-labeling, the cells were lysed in capsid extraction buffer on ice for 30 min and centrifuged in a microcentrifuge as described above. For chase experiments, the labeling medium was removed and complete medium was added for 4 h, after which the cells were lysed as above. The supernatant of each cell lysate was centrifuged through a sucrose velocity gradient as described above for insect cell lysates. Sucrose velocity gradient fractions and cell culture medium were immunoprecipitated and analyzed as described above for insect cells.

RESULTS

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of both M-PMV and HIV-1 gag expression in Sf9 and High Five insect cells.

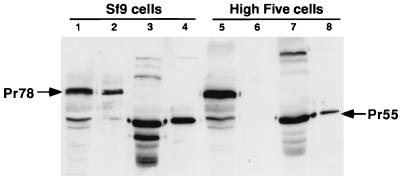

To compare the relative amounts of M-PMV and HIV-1 Gag in infected cell lysates and cell supernatants, 2% of each Sf9 and High Five cell lysate and 2% of each cell medium pellet were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting and detection of Gag polyproteins with Gag-specific antisera. The results (Fig. 1) show nearly equal amounts of Gag in the cell lysate and supernatant of Sf9 cells for both M-PMV and HIV-1. In contrast, M-PMV Gag was absent from the cell supernatant of High Five cells and HIV-1 Gag levels in the supernatant were markedly reduced compared to those in Sf9 cells. While this analysis does not provide a quantitative measure of Gag release from infected cells, the results clearly demonstrate the inefficiency of both HIV-1 and M-PMV Gag release from High Five cells. In the case of M-PMV, Gag release was blocked below the level of detection in this experiment whereas the effect on HIV-1 Gag release was less dramatic.

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of insect cell lysates and cell culture media. Following the expression of M-PMV Gag in Sf9 cells, Pr78Gag can be seen in both the cell lysate (lane 1) and the cell culture medium (lane 2). HIV Pr55Gag can also be seen in the cell lysate (lane 3) and culture medium (lane 4) of Sf9 cells. In contrast, following the expression of M-PMV Gag in High Five cells, Pr78Gag is seen in the cell lysate (lane 5) but is absent in the cell culture medium (lane 6). HIV Pr55Gag is seen in the High Five lysate (lane 7) and cell culture medium (lane 8), but the amount of Pr55Gag in the culture medium is markedly reduced compared with that in Sf9 cells.

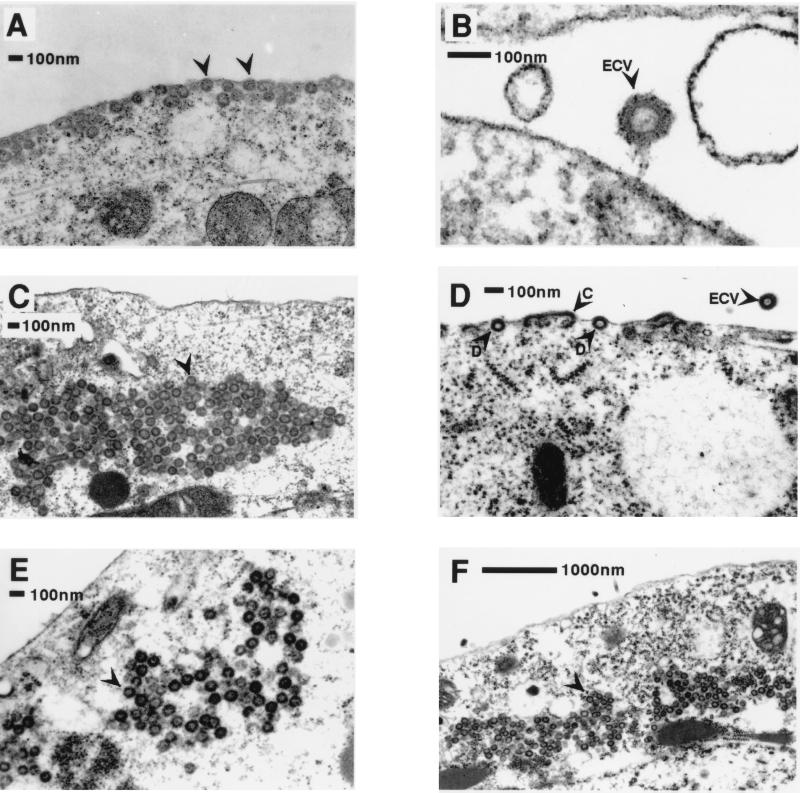

EM analysis of baculovirus-infected insect cells expressing retroviral gag gene products.

To further study the assembly and transport characteristics of M-PMV and HIV Gag polyproteins in insect cell lines, both Sf9 and High Five cells infected with recombinant baculovirus-expressing retroviral gag gene products were fixed and imaged by thin-section EM. In Sf9 cells, M-PMV Gag polyproteins had assembly and transport characteristics very similar to previously described results obtained from proviral genomic expression in mammalian cell lines (Fig. 2) (40, 42). M-PMV Gag polyproteins with a wild-type matrix domain (Fig. 2A and B) assembled within the cytoplasm of Sf9 cells, and this was followed by transport of intact capsids to the plasma membrane for budding and release of enveloped VLPs. When the A18V point mutation was introduced into the matrix domain (Fig. 2C), capsid assembly was unaffected but transport to the plasma membrane was completely deficient and viral capsids accumulated within the cytoplasm of the infected cell. This phenotype is identical to that described previously in mammalian cells (40). With the R55W matrix point mutation, there was evidence of D-type assembly with relatively small collections of particles retained in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2E), as well as both D-type and C-type budding at the plasma membrane (Fig. 2D). In mammalian cells, R55W Gag expression resulted primarily in C-type Gag assembly at the plasma membrane, with rare collections of particles in the cytoplasm (39). EM images of insect cells expressing Gag polyproteins with both A18V and R55W matrix point mutations (Fig. 2F) are identical to images of cells expressing A18V Gag, and neither C- nor D-type viral budding was seen at the cell surface. The behavior of this double mutant in mammalian cells was the same as that observed in insect cells (data not shown). Thus, the A18V mutation effectively blocks the transport of intact M-PMV capsids as well as individual unassembled or partially assembled Gag polyproteins to the cell surface and is cis dominant when coexpressed with the R55W matrix point mutation.

FIG. 2.

Thin-section EM of Sf9 cells expressing M-PMV gag genes. (A and B) Wild-type M-PMV Gag expression shows fully assembled immature capsids budding from the plasma membrane (arrowheads) and extracellular pseudovirions (arrowhead labeled ECV). (C) A18V Gag expression shows assembled immature capsids accumulating in the cytoplasm (arrowhead) with no evidence of viral budding at the plasma membrane. (D and E) R55W Gag expression (D) shows both C-type assembly at the plasma membrane (arrowhead labeled C) and the budding of fully assembled immature capsids (arrowheads labeled as D), extracellular pseudovirions (arrowhead labeled ECV), and rare collections of assembled particles retained in the cytoplasm (E). (F) Gag with both A18V and R55W point mutations shows cytoplasmic immature capsids (arrowhead) with no evidence of viral budding.

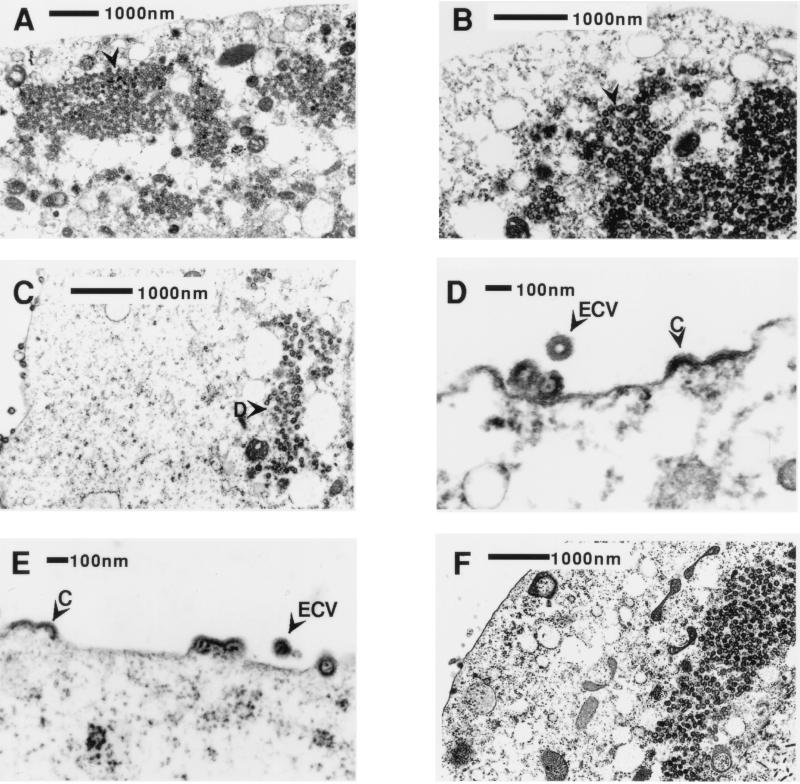

In High Five insect cells, wild-type M-PMV Gag polyproteins assembled into immature capsids but there was a striking block to intracellular transport (Fig. 3A). Wild-type immature capsids accumulated in the cytoplasm in large inclusions but were not transported to the plasma membrane. This phenotype is similar to that seen with the A18V point mutation in these cells (Fig. 3B), as well as in mammalian and Sf9 insect cells. In contrast, some of the M-PMV Gag polyproteins with the R55W matrix mutation were transported to the plasma membrane of High Five cells to initiate C-type viral budding (Fig. 3C to E). R55W Gag also assembled as D-type immature capsids in the cytoplasm, and D-type particle retention in the cytoplasm is evident. While there is some evidence of completed capsids budding at the plasma membrane, this may represent the completion of C-type assembly in advance of membrane extrusion, since no capsids were seen in transit to the plasma membrane. M-PMV Gag with both A18V and R55W point mutations (Fig. 3F) assembled in the cytoplasm of High Five cells, and neither C- nor D-type budding was seen at the plasma membrane, consistent with the dominant nature of the A18V mutation discussed above. Thus, High Five cells have a defect in the cytoplasmic transport of M-PMV Gag in the form of assembled immature capsids, which is less pronounced for unassembled Gag polyproteins.

FIG. 3.

Thin-section EM of High Five cells expressing M-PMV gag genes. (A and B) Both wild-type M-PMV Gag (A) and A18V M-PMV Gag (B) expression show assembled immature capsids accumulating in the cytoplasm with no evidence of viral budding at the plasma membrane. (C to E) R55W Gag expression shows D-type assembly and retention in the cytoplasm (arrowhead labeled as D) as well as C-type viral budding at the plasma membrane (arrowheads labeled C) and extracellular VLPs (arrowheads labeled ECV). (F) Gag with both A18V and R55W point mutations shows accumulation of immature capsids in the cytoplasm with no viral budding at the plasma membrane.

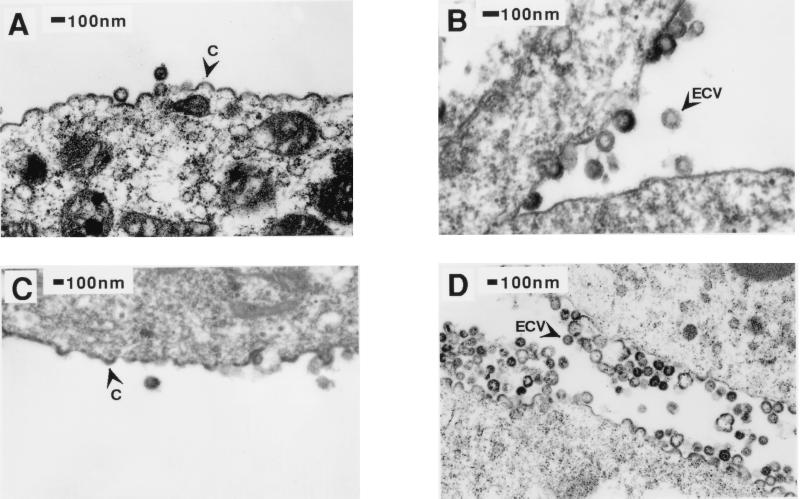

HIV-1 Gag polyproteins assembled in C-type fashion at the plasma membrane of mammalian cells, and similar transport and assembly characteristics were seen in Sf9 insect cells (Fig. 4A and B), including the release of enveloped extracellular VLPs. In contrast to wild-type M-PMV, there was clear evidence of HIV-1 Gag polyproteins, in the form of numerous C-type budding structures, at the plasma membrane of High Five cells (Fig. 4C). The amount of C-type viral budding activity at the plasma membrane in High Five cells (Fig. 4D) appeared similar to that seen in Sf9 cells; however, as shown in Fig. 1 and addressed below, the release of these assembling structures was significantly reduced. Evidence of C-type budding of HIV-1 and M-PMV R55W Gag polyproteins at the plasma membrane of High Five cells suggests that a common transport mechanism is involved in both cases.

FIG. 4.

Thin-section EM of HIV-1 gag gene expression in both Sf9 (A and B) and High Five (C and D) cell lines. In both cell lines, C-type budding events are seen at the plasma membrane (arrowheads labeled C) and extracellular VLPs (arrowheads labeled ECV) are seen in the spaces between adjacent cells.

Metabolic labeling of Sf9 and High Five insect cells expressing retroviral gag gene products.

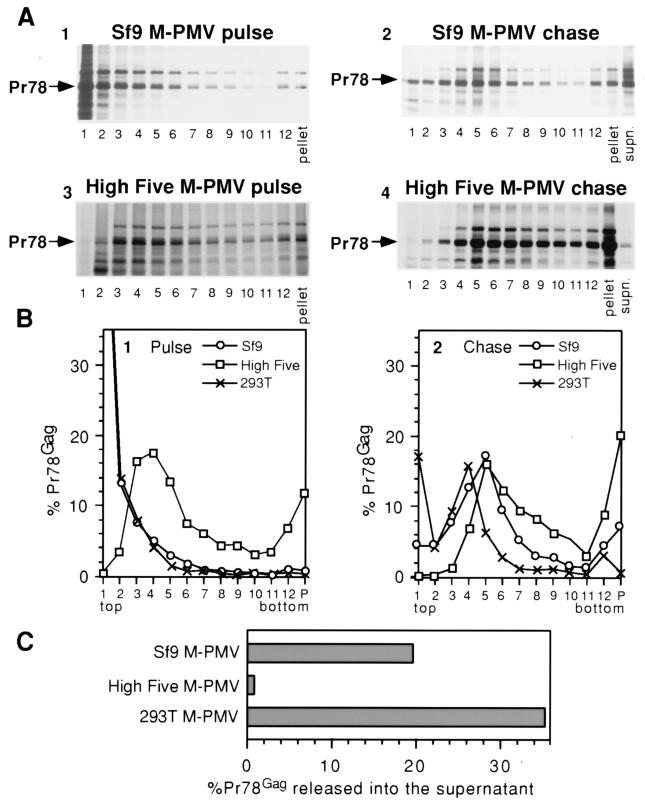

To quantitatively compare the kinetics of retroviral assembly and the release of extracellular pseudovirions in the two different insect cell lines, metabolic labeling studies were performed. Immediately following a 30-min labeling period or a 14-h chase period, Sf9 and High Five cells were lysed in nonionic detergent, under conditions known to keep intracellular immature capsids intact (40). The cell lysates were fractionated by velocity sucrose gradient sedimentation, and each fraction was analyzed together with a resuspension of the gradient pellet and the cell culture medium by immunoprecipitation and SDS-PAGE. After pulse-labeling of Sf9 cells, the soluble, unassembled wild-type M-PMV Gag polyproteins remained in the fractions at the very top of the 5 to 20% sucrose velocity gradients and there was no discrete peak within the gradient suggesting the accumulation of assembly intermediates (Fig. 5A and B, panels 1). In contrast, after a 14-h chase period, approximately 35% of the Pr78Gag was found in assembled immature capsids, which sedimented to lower fractions (fractions 4, 5, and 6) within the gradient (Fig. 5A and B, panels 2). In addition, approximately 20% of the total Pr78Gag was released into the culture medium (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

SDS-PAGE analysis and quantitation of wild-type M-PMV Gag in insect and mammalian cell lysates and cell culture medium. After metabolic labeling, cell lysates were centrifuged through a sucrose gradient, and fractions were collected from the top of the gradient tubes, beginning with fraction 1 and ending with the resuspension of the gradient pellet. (A) Each gradient fraction and the cell culture medium (labeled supn.) from the chase were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the autoradiograms from the insect cell expression are shown. (B) The intensity of the Gag band in each velocity gradient fraction is graphed as a percentage of the total of all bands from the same pulse or chase experiment, including the culture medium for chase experiments. (C) The intensity of the Gag band representing each cell chase culture medium is graphed as a percentage of the total of all Gag bands (cell lysate fractions and culture medium) from the same chase experiment.

To compare expression in mammalian cells to that in insect cells, human 293T cells were transfected with M-PMV proviral DNA, pulse-labeled, or pulse-labeled and then chased for 4 h. The cell lysates were fractionated on velocity sucrose gradients as above. In pulse-labeled 293T cells, the M-PMV Gag remained in unassembled form at the top of the gradient, as was seen with Sf9 cells, whereas after a 4-h chase, approximately 30% of the labeled M-PMV Gag was found as assembled capsids (Fig. 5B, panel 2, fractions 3, 4, and 5). Approximately 35% of the Pr78 remaining after the chase was released as VLPs in the culture medium of the cells (Fig. 5C). The sedimentation profile of M-PMV capsids assembled in insect cells was confirmed by fractionating purified M-PMV capsids from baculovirus-infected insect cells in parallel gradients. These capsids were also localized to fractions 4, 5, and 6 (data not shown). Thus, the assembly, intracellular transport, and release of M-PMV Gag in Sf9 insect cells and in mammalian cells is similar.

The results obtained with High Five cells expressing wild-type M-PMV Gag were significantly different. Whereas M-PMV Gag from pulse-labeled Sf9 cell lysates remained at the top of the gradient, M-PMV Gag polyproteins from pulse-labeled High Five cell lysates sedimented into the gradient to fractions 3, 4, and 5 (Fig. 5A, panel 3, and Fig. 5B, panel 1). This could reflect an accelerated assembly of partial capsids that now sediment into the gradient or, more probably, the association of Gag polyproteins with cellular elements to yield complexes with a higher mass. After the chase period, M-PMV Gag polyproteins from the High Five cell lysates sedimented as assembled capsids with maximal values in fractions 5 and 6 (Fig. 5B, panel 2). However, the peak of Pr78 trailed appreciably into the denser portion of the gradient and significantly more material was found in the pellet, possibly as a consequence of an association with cellular elements. Very little (<2%) M-PMV Pr78 could be detected in the culture medium of M-PMV Gag-expressing High Five cells following the chase (Fig. 5C).

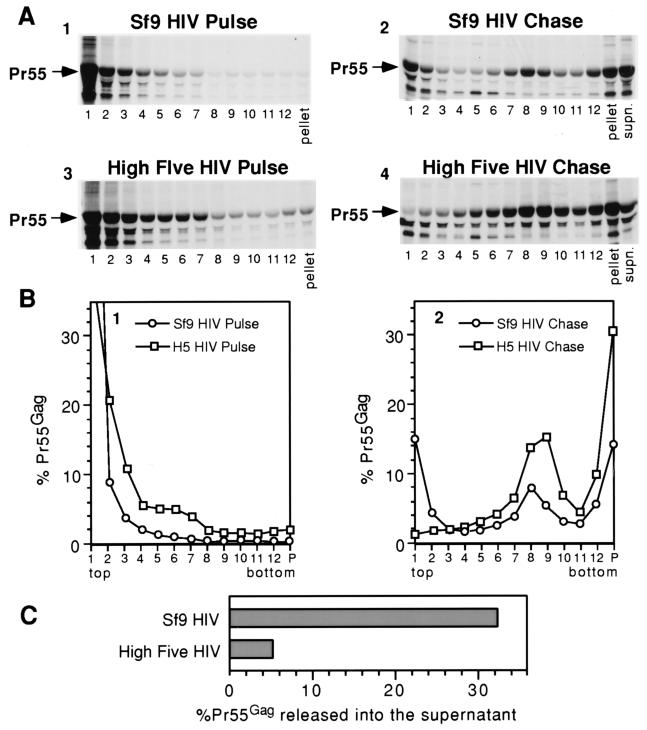

Expression of HIV-1 Gag in SF9 cells yielded results very similar to that described for M-PMV Gag above. In pulse-labeled cells, the bulk of Pr55Gag was unassembled and was found in the top two fractions of the gradient (Fig. 6A and B, panels 1). After a 14-h chase, approximately 20% of Pr55Gag remained soluble while approximately 15 to 20% sedimented to fractions 7, 8, and 9 (Fig. 6B, panel 2). This presumably represents the assembled immature capsids that remain cell associated even after the 14-h chase. One-third of the HIV-1 Gag from SF9 cells was released into the cell culture medium as VLPs following the 14-h chase (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 6.

SDS-PAGE analysis and quantitation of HIV-1 Gag in insect cell lysates and in cell culture medium. After metabolic labeling, cell lysates were centrifuged through a sucrose gradient, and fractions were collected from the top of the gradient tubes, beginning with fraction 1 and ending with the resuspension of the gradient pellet. (A) Each gradient fraction and the cell culture medium (labeled supn.) from the chase were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the autoradiograms are shown. (B) The intensity of the Gag band in each Sf9 and High Five (H5) velocity gradient fraction is graphed as a percentage of the total of all bands from the same pulse or chase experiment, including the culture medium for chase experiments. (C) The intensity of the Gag band representing each cell chase culture medium is graphed as a percentage of the total of all Gag bands (cell lysate fractions and culture medium) from the same chase experiment.

In contrast to M-PMV, the bulk of the HIV-1 Gag polyprotein from pulse-labeled High Five cell lysates remained in the first two gradient fractions (Fig. 6A, panel 3, and Fig. 6B, panel 1). However, approximately 20% did sediment into fractions 3, 4, 5, and 6, raising the possibility that a fraction of HIV-1 Gag also associates with a cellular component in High Five cells. Following the 14-h chase period, approximately 30% of Pr55 was found in fractions 8 and 9 (Fig. 6B, panel 2), again presumably representing assembled but cell-associated HIV Gag polyproteins. In contrast to Sf9 cells, however, approximately 30% of the HIV-1 Gag was found in the pellet fraction and there was <2% soluble Pr55 at the top of the gradient. This finding may be a consequence of Pr55 association with cellular elements in High Five cells, as discussed with M-PMV Gag above. Although extracellular VLPs were seen by EM, less than 6% of Pr55 was released into the High Five culture medium (Fig. 6C). The reduced levels of both HIV and M-PMV R55W (see below) extracellular VLPs from High Five cells, despite the EM data presented above, suggest that these cells are also somewhat defective in the release of C-type VLPs.

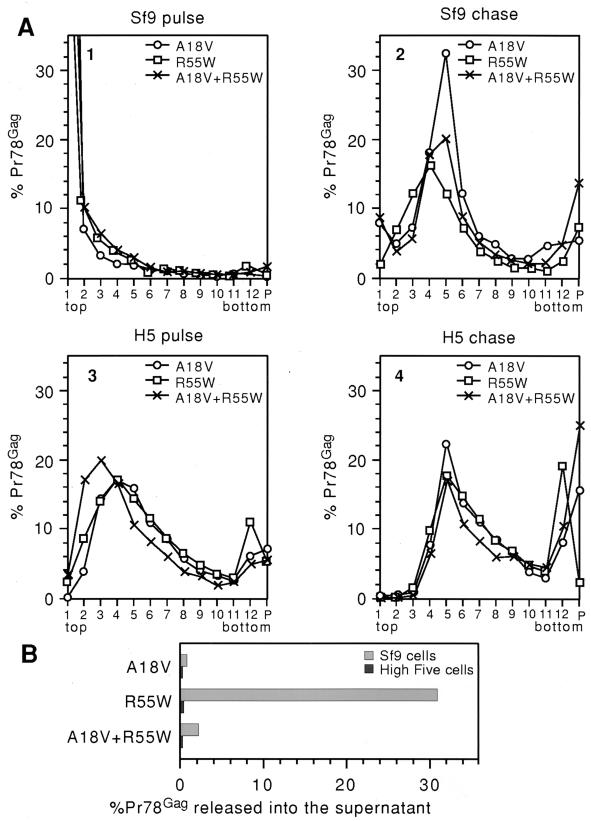

As discussed above, the A18V matrix mutation blocks the transport of immature M-PMV capsids in all cell lines studied to date. Velocity gradient fractions from Sf9 cell lysates with A18V M-PMV Gag had a profile similar to that seen with the expression of wild-type M-PMV Gag, with the exception of an increase in the number of immature intracellular capsids in the Sf9 chase cell lysate (Fig. 7A, panel 2, fractions 4, 5, and 6). In contrast to wild-type M-PMV Gag, less than 1% of the A18V Pr78Gag was released into the culture medium (Fig. 7B), demonstrating the effect of the intracellular transport block seen in the EM analysis (see above). The velocity gradient profiles of R55W Gag in the pulse and chase Sf9 cell lysate fractions were not significantly different from those of wild-type M-PMV Gag, but there was an increase in the fraction of R55W Pr78Gag released into the culture medium after a 14-h chase (30% R55W Pr78 released [Fig. 7B]). The fraction of C-type R55W Pr78Gag released from Sf9 cells was similar to that seen with C-type HIV-1 Pr55Gag (see above).

FIG. 7.

SDS-PAGE analysis and quantitation of M-PMV Gag with matrix mutations (A18V, R55W, and the A18V/R55W double mutant) in Sf9 and High Five (H5) cell lysates and in cell culture medium. After metabolic labeling, cell lysates were centrifuged through a sucrose gradient, and fractions were collected from the top of the gradient tubes, beginning with fraction 1 and ending with the resuspension of the gradient pellet. (A) Each gradient fraction and the cell culture medium from the chase were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the relative intensity of the Gag band in each velocity gradient fraction is graphed as a percentage of the total of all bands from the same pulse or chase experiment, including the culture medium for chase experiments. (B) The intensity of the Gag band representing each cell chase supernatant is graphed as a percentage of the total of all Gag bands (cell lysate fractions and culture medium) from the same chase experiment.

The expression of the A18V and R55W matrix mutant M-PMV Gag polyproteins in High Five cells yielded results similar to those seen with wild-type M-PMV Gag in these cells. In pulse-labeled High Five cells, both R55W and A18V Gag sedimented into fractions 3, 4, and 5 (Fig. 7A, panel 3). Although M-PMV R55W Gag and HIV-1 Gag both demonstrated C-type assembly at the plasma membrane in High Five cells, the pulse-labeled velocity gradient profiles were very different (Fig. 6B, panel 1 and Fig. 7A, panel 3). If an interaction with a cellular element(s) is responsible for the M-PMV pulse-labeled velocity gradient profile in High Five cells, this interaction must not completely interfere with the transport of M-PMV R55W Gag to the plasma membrane. While C-type budding structures were seen with M-PMV R55W Gag in High Five cells (see the EM analysis above), less than 1% of the R55W Pr78 was released into the High Five cell culture medium (Fig. 7B). As discussed above, High Five cells may have a defect in the release of extracellular VLPs that is independent from the M-PMV Gag transport defect.

M-PMV Gag expression with a double matrix mutant (A18V and R55W) yielded results very similar to those seen with the A18V matrix mutant alone (Fig. 7). Thus, the A18V mutation acts as a dominant negative transport block, which confirms the findings in the EM analysis above.

DISCUSSION

For most retroviruses (spumaviruses being the notable exception), the release of an enveloped extracellular virus particle requires that Gag polyproteins interact specifically with the plasma membrane during the viral budding process. The fact that viral budding is limited only to the plasma membrane argues that cellular transport mechanisms must actively direct retroviral Gag polyproteins exclusively to this cellular location. There are other lines of evidence to suggest that host cell factors are involved in Gag polyprotein transport. Cell ATP depletion studies demonstrate that ATP is required for M-PMV Gag transport, suggesting an active involvement of cellular proteins with ATPase activity in the process (57). HIV-1 Gag interacts with both microtubules and microfilaments as a possible mechanism of an active-transport process (24, 27, 38, 58). In addition, a Gag receptor residing exclusively at the plasma membrane may be required to insert and anchor the Gag matrix domain into the plasma membrane (proposed in reference 59). The directional budding and secretion of HIV-1 virions observed when infected monocytes adhere to epithelial cell monolayers also suggests that the interaction of host cell factors with retroviral Gag polyproteins is necessary to coordinate the assembly and release of an enveloped extracellular VLP (35). Although T-cell and monocyte cell lines in which HIV-1 Gag polyproteins are transported to alternative cell membranes for viral budding have been reported (18, 31, 34), host cell lines completely defective in the active transport of retroviral immature capsids or unassembled Gag polyproteins have not been described.

In Sf9 insect cells, expression of either M-PMV or HIV gag gene products results in D- or C-type immature-capsid assembly, respectively, followed by viral budding and release of extracellular VLPs (17, 49). Thus, these insect cells have the capacity for the transport of both C- and D-type Gag polyproteins to the plasma membrane and allow the completion of the viral budding process, even in the presence of baculovirus cytopathic effect. Compared with Sf9 cells, High Five insect cells have a defect in the transport of assembled capsids to the plasma membrane that interferes with the release of extracellular VLPs. Imaging of High Five insect cells by thin-section EM reveals that wild-type M-PMV immature capsids are assembled in the cytoplasm but are not transported to the plasma membrane. In contrast, similar numbers of budding structures were observed in EM studies of both Sf9 and High Five cell lines expressing HIV-1 Gag and in cells expressing M-PMV R55W Gag. Although not quantitative, these observations suggest that Gag precursors that assemble at the plasma membrane can be transported there with similar efficiency in both cell types. The R55W mutation allows at least a fraction of unassembled M-PMV Gag polyproteins to escape the transport defect in High Five cells but not the transport defect imposed by the A18V mutation, suggesting that a different mechanism is involved for each defect. If the effect of the A18V mutation is a lack of active transport to the plasma membrane, the High Five cell defect may be a consequence of a restrictive cytoplasmic retention mechanism that can be relieved by the R55W mutation. As an alternative, there may be separate and independent mechanisms for the transport of assembled capsids and unassembled Gag polyproteins. High Five cells may then have a selective defect in the macromolecular transport of assembled M-PMV capsids while the transport of unassembled Gag polyproteins remains intact. In either case, it is clear that High Five cells have a missing or altered host cell factor(s) that participates in the transport of D-type particles but is less important in the transport of unassembled Gag polyproteins.

The metabolic labeling experiments of insect cells expressing gag gene products demonstrate another defect in the release of extracellular VLPs from High Five cells. A quantitative analysis of the amount of M-PMV and HIV Gag in the culture medium of Sf9 cells shows that a significant fraction of both C- and D-type Gag polyproteins complete the viral budding process and are released as extracellular pseudovirions. The same analysis in High Five cells shows a marked reduction in the release of both C- and D-type VLPs. While the absence of D-type M-PMV Gag in the culture medium of High Five cells is explained by the transport defect observed by thin-section EM, the marked reduction in C-type polyproteins is not. The metabolic labeling experiments offer a more quantitative measurement of extracellular particle release, and they suggest, when coupled with the EM data, that although C-type Gag polyproteins are transported to the plasma membrane of High Five cells and initiate viral budding, there is a defect in the completion of viral budding and the release of enveloped VLPs. This second cell-dependent defect is consistent with a number of previous studies that have suggested a role for host cell factors in the completion of the viral budding event (8, 20, 33, 37, 61).

Pulse-chase-labeled insect cell lysates were fractionated by sucrose velocity gradient sedimentation to measure the proportion of Gag polyproteins that have assembled into immature capsids during the chase period. As a consistent but unexpected finding, M-PMV and to a lesser extent HIV Gag polyproteins in pulse-labeled High Five cell lysates sediment into the gradient by several fractions. In contrast, both M-PMV and HIV-1 Gag in pulse-labeled Sf9 cell lysates remain in the top fractions of the gradient, as expected after a short labeling period with insufficient time allowed for capsid assembly. M-PMV capsid assembly within a short labeling period is inconsistent with a previous characterization of M-PMV assembly kinetics in mammalian cells (40) and is an unlikely explanation of the M-PMV Gag sedimentation characteristics in the pulse-labeled High Five cell lysate velocity gradients. High Five cells have a moderate increase (two- to threefold [data not shown]) in Gag expression levels compared with Sf9 cells, but this difference is not likely to result in accelerated immature capsid assembly. A more plausible explanation is that M-PMV Gag and, to a lesser extent, HIV-1 Gag may bind to cellular structures to form a complex with a higher S value shortly after synthesis in High Five cells and that this association may persist during cell lysis and velocity gradient sedimentation. Pulse-labeled M-PMV Gag binding to cellular structures may be a consequence of a restrictive cytoplasmic retention system and may explain the D-type transport defect observed in High Five cells. Although C-type M-PMV Gag (R55W) is capable of being transported to the plasma membrane in High Five cells, a significant number of particles are also retained in the cytoplasm, which may explain the similar appearance of wild-type and R55W M-PMV Gag in the High Five cell lysate velocity gradient analysis.

In conclusion, the High Five insect cell line has separate defects involving the transport of retroviral Gag polyproteins to the plasma membrane and the completion of the viral budding event. The transport defect is most pronounced for D-type M-PMV Gag polyproteins, suggesting that the efficiency of D-type Gag transport is sensitive to alterations in host cell factors that are less important in C-type Gag transport. The budding and release defect observed with C-type Gag polyproteins argues that host cell factors can assist or interfere with the efficient completion of the viral budding event and release of an extracellular VLP. Host cell lines with specific and dramatic defects in these late stages in the retroviral life cycle have not been described to date, and the findings reported here provide convincing evidence for the involvement of cellular factors during Gag transport and viral budding. The High Five cell line may prove to be a useful tool in the search for specific host cell factors that assist or interfere with the efficient intracellular transport of Gag polyproteins and with the production of an extracellular virus particle.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Eugene Arms and the UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center electron microscopy facility for assistance with the electron microscopic analysis.

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants AI01263 to S.D.P. and CA27834 to E.H.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bradac J, Hunter E. Polypeptides of the Mason-Pfizer monkey virus I. Synthesis and processing of the gag-gene products. Virology. 1984;138:260–275. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90350-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell S, Rein A. In vitro assembly properties of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein lacking the p6 domain. J Virol. 1999;73:2270–2279. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2270-2279.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell S, Vogt V M. In vitro assembly of virus-like particles with Rous sarcoma virus Gag deletion mutants: identification of the p10 domain as a morphological determinant in the formation of spherical particles. J Virol. 1997;71:4425–4435. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4425-4435.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chazal N, Gay B, Carriere C, Tournier J, Boulanger P. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 MA deletion mutants expressed in baculovirus-infected cells: cis and trans effects on the Gag precursor assembly pathway. J Virol. 1995;69:365–375. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.365-375.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen C, Okayama H. High-efficiency transformation of mammalian cells by plasmid DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2745–2752. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi G, Park S, Choi B, Hong S, Lee J, Hunter E, Rhee S S. Identification of a cytoplasmic targeting/retention signal in a retroviral Gag polyprotein. J Virol. 1999;73:5431–5437. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5431-5437.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Compans R W, Holmes K V, Dales S, Choppin P W. An electron microscopic study of moderate and virulent virus-cell interactions of the parainfluenza virus SV5. Virology. 1964;30:411–426. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(66)90119-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Craven R C, Harty R N, Paragas J, Palese P, Wills J W. Late domain function identified in the vesicular stomatitis virus M protein by use of rhabdovirus-retrovirus chimeras. J Virol. 1999;73:3359–3365. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3359-3365.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delchambre M, Gheysen D, Thines D, Thiriart C, Jacobs E, Verdin E, Horth M, Burny A, Bex F. The Gag precursor of simian immunodeficiency virus assembles into virus-like particles. EMBO J. 1989;8:2653–2660. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08405.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dickson C, Eisenman R, Fan H, Hunter E, Teich N. Protein biosynthesis and assembly. In: Weiss R, Teich N, Varmus H, Coffin J, editors. RNA tumor viruses. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. pp. 513–648. [Google Scholar]

- 11.DuBridge R B, Tang P, Hsia H C, Leong P M, Miller J H, Calos M P. Analysis of mutation in human cells by using an Epstein-Barr virus shuttle system. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:379–387. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.1.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Facke M, Janetzko A, Shoeman R, Krausslich H. A large deletion in the matrix domain of the human immunodeficiency virus gag gene redirects virus particle assembly from the plasma membrane to the endoplasmic reticulum. J Virol. 1993;67:4972–4980. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4972-4980.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fine D, Schochetman G. Type D primate retroviruses: a review. Cancer Res. 1978;38:3123–3139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher A G, Ratner L, Mitsuya H, Marselle L M, Harper M E, Broder S, Gallo R C, Wong-Staal F. Infectious mutants of HTLV-III with changes in the 3′ region and markedly reduced cytopathic effects. Science. 1986;233:655–659. doi: 10.1126/science.3014663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gelderblom H, Hausmann E, Ozel M, Pauli G, Koch M. Fine structure of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and immunolocalization of structural proteins. Virology. 1987;156:171–176. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90449-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gelderblom H R. Assembly and morphology of HIV: potential effect of structure on viral function. AIDS. 1991;5:617–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gheyson D, Jacobs E, Foresta F d, Thiriart C, Francotte M, Thines D, Wilde M D. Assembly and release of HIV-1 precursor Pr55gag virus like particles from recombinant baculovirus infected insect cells. Cell. 1989;59:103–112. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90873-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grief C, Farrar G H, Kent K A, Berger E G. The assembly of HIV within the Golgi apparatus and Golgi-derived vesicles of JM cell syncytia. AIDS. 1991;5:1433–1439. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199112000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gross I, Hohenberg H, Huckhagel C, Krausslich H-G. N-terminal extension of human immunodeficiency virus capsid protein converts the in vitro assembly phenotype from tubular to spherical particles. J Virol. 1998;72:4798–4810. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4798-4810.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harty R N, Paragas J, Sudol M, Palese P. A proline-rich motif within the matrix protein of vesicular stomatitis virus and rabies virus interacts with WW domains of cellular proteins: implications for viral budding. J Virol. 1999;73:2921–2929. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2921-2929.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henderson L, Krutzsch H, Oroszlan S. Myristyl amino-terminal acylation of murine retrovirus proteins: an unusual post-translational protein modification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:339–343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.2.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoshikawa N, Kojima A, Yasuda A, Takayashiki E, Masuko S, Chiba J, Sata T, Kurata T. Role of the gag and pol genes of human immunodeficiency virus in the morphogenesis and maturation of retrovirus-like particles expressed by recombinant vaccinia virus: an ultrastructural study. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:2509–2517. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-10-2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karacostas V, Nagashima K, Gonda M A, Moss B. Human immunodeficiency virus-like particles produced by a vaccinia virus expression vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:8964–8967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.22.8964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim W, Tang Y, Okada Y, Torrey T A, Chattopadhyay S K, Pfleiderer M, Falkner F G, Dorner F, Choi W, Hirokawa N, Morse H C., III Binding of murine leukemia virus Gag polyproteins to KIF4, a microtubule-based motor protein. J Virol. 1998;72:6898–6901. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6898-6901.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krausslich H G, Welker R. Intracellular transport of retroviral capsid components. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;214:25–63. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80145-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leis J, Baltimore D, Bishop J, Coffin J, Fleissner E, Goff S, Oroszlan S, Robinson H, Skalka A, Temin H, Vogt V. Standardized and simplified nomenclature for proteins common to all retroviruses. J Virol. 1988;62:1808–1809. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.5.1808-1809.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu B, Dai R, Tian C J, Dawson L, Gorelick R, Yu X F. Interaction of the human immunodeficiency virus type nucleocapsid with actin. J Virol. 1999;73:2901–2908. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2901-2908.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mergener K, Facke M, Welker R, Brinkmann V, Gelderblom H R, Krausslich H G. Analysis of HIV particle formation using transient expression of subviral constructs in mammalian cells. Virology. 1992;186:25–39. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90058-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ono A, Freed E O. Binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag to membrane: role of the matrix amino terminus. J Virol. 1999;73:4136–4144. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.4136-4144.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Reilly D R, Miller L K, Luckow V A. Baculovirus expression vectors—a laboratory manual. W. H. New York, N.Y: Freeman & Co.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orenstein J M, Meltzer M S, Phipps T, Gendelman H E. Cytoplasmic assembly and accumulation of human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 in recombinant human colony-stimulating factor-1-treated human monocytes: an ultrastructural study. J Virol. 1988;62:2578–2586. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2578-2586.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paillart J C, Gottlinger H G. Opposing effects of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix mutations support a myristyl switch model of gag membrane targeting. J Virol. 1999;73:2604–2612. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2604-2612.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parent L J, Bennett R P, Craven R C, Nelle T D, Krishna N K, Bowzard J B, Wilson C B, Puffer B A, Montelaro R C, Wills J W. Positionally independent and exchangeable late budding functions of the Rous sarcoma virus and human immunodeficiency virus Gag proteins. J Virol. 1995;69:5455–5460. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5455-5460.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pautrat G, Suzan M, Salaun D, Corbeau P, Allasia C, Morel G, Filippi P. Human immunodeficiency virus type-1 infection of U937 cells promotes cell differentiation and a new pathway of viral assembly. Virology. 1990;179:749–758. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90142-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pearce-Pratt R, Malamud D, Phillips D M. Role of the cytoskeleton in cell-to-cell transmission of human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1994;68:2898–2905. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.2898-2905.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pepinsky R, Vogt V. Identification of retrovirus matrix proteins by lipid-protein cross-linking. J Mol Biol. 1979;131:819–837. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puffer B A, Parent L J, Wills J W, Montelaro R C. Equine infectious anemia virus utilizes a YXXL motif within the late assembly domain of the Gag p9 protein. J Virol. 1997;71:6541–6546. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6541-6546.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rey O, Canon J, Krostad P. HIV-1 Gag protein associates with F-actin present in microfilaments. Virology. 1996;220:530–534. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rhee S, Hui H, Hunter E. Preassembled capsids of type D retroviruses contain a signal sufficient for targeting specifically to the plasma membrane. J Virol. 1990;64:3844–3852. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.8.3844-3852.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rhee S, Hunter E. Amino acid substitutions within the matrix protein of type D retroviruses affect assembly, transport and membrane association of a capsid. EMBO J. 1991;10:535–546. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07980.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rhee S, Hunter E. Myristylation is required for intracellular transport but not for assembly of D-type retrovirus capsids. J Virol. 1987;61:1045–1053. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.4.1045-1053.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rhee S, Hunter E. A single amino acid substitution within the matrix protein of a type D retrovirus converts its morphogenesis to that of a type C retrovirus. Cell. 1990;63:77–86. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90289-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rhee S, Hunter E. Structural role of the matrix protein of type D retroviruses in Gag polyprotein stability and capsid assembly. J Virol. 1990;64:4383–4389. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4383-4389.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Royer M, Cerutti M, Gay B, Hong S-S, Devauchelle G, Boulanger P. Functional domains of HIV-1 Gag-polyprotein expressed in baculovirus-infected cells. Virology. 1991;184:417–422. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90861-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sakalian M, Parker S, Weldon R, Jr, Hunter E. Synthesis and assembly of retrovirus Gag precursors into immature capsids in vitro. J Virol. 1996;70:3706–3715. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3706-3715.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakalian M, Weldon R, Jr, Hunter E. Separate assembly and transport domains within the Gag precursor of Mason-Pfizer monkey virus. J Virol. 1999;73:8073–8082. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8073-8082.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Manatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shioda T, Shibuta H. Production of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-like particles from cells infected with recombinant vaccinia viruses carrying the gag gene of HIV. Virology. 1990;175:139–148. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90194-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sommerfelt M, Roberts C, Hunter E. Expression of simian type D retroviral (Mason-Pfizer monkey virus) capsids in insect cells using recombinant baculovirus. Virology. 1993;192:298–306. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sonigo P, Barker C, Hunter E, Wain-Hobson S. Nucleotide sequence of Mason-Pfizer monkey virus: an immunosuppressive D-type retrovirus. Cell. 1986;45:375–385. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90323-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spearman P, Ratner L. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid formation in reticulocyte lysates. J Virol. 1996;70:8187–8194. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8187-8194.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spearman P, Wang J, Vander Heyden N, Ratner L. Identification of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein domains essential to membrane binding and particle assembly. J Virol. 1994;68:3232–3242. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3232-3242.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Streblow D N, Kitabwalla M, Pauza C D. Gag protein from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembles in the absence of cyclophilin A. Virology. 1998;252:228–234. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takahashi R H, Nagashima K, Kurata T, Takahashi H. Analysis of human lymphotropic T-cell virus type II-like particle production by recombinant baculovirus-infected insect cells. Virology. 1999;256:371–380. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Temin H M. Origin and general nature of retroviruses. In: Levy J A, editor. The Retroviridae. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1992. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vogt V M. Proteolytic processing and particle maturation. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;214:94–131. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80145-7_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weldon R, Jr, Parker W, Sakalian M, Hunter E. Type D retrovirus capsid assembly and release are active events requiring ATP. J Virol. 1998;72:3098–3106. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3098-3106.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilk T, Gowen B, Fuller S D. Actin associates with the nucleocapsid domain of the human immunodeficiency virus Gag polyprotein. J Virol. 1999;73:1931–1940. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.1931-1940.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wills J W, Craven R C. Form, function and use of retroviral Gag proteins. AIDS. 1991;5:639–654. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199106000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yamshchikov G V, Ritter G D, Vey M, Compans R W. Assembly of SIV virus-like particles containing envelope proteins using a baculovirus expression system. Virology. 1995;214:50–58. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.9955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yasuda J, Hunter E. A proline rich motif (PPPY) in the Gag polyprotein of Mason-Pfizer monkey virus plays a maturation-independent role in virion release. J Virol. 1998;72:4095–4103. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4095-4103.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yuan X, Yu X, Lee T, Essex M. Mutations in the N-terminal region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix block intracellular transport of the Gag precursor. J Virol. 1993;67:6387–6394. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6387-6394.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]