Abstract

Bone and soft tissue sarcomas (BSTSs) are rare malignant tumors of mesenchymal origin. Although BSTSs frequently occur in some hereditary cancer syndromes with germline mutations of DNA repair genes, genetic factors responsible for sporadic cases have not been determined. In the present study we undertook a case‐control study and analyzed possible associations between the susceptibility to BSTS and the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in DNA repair genes. Genomic DNAs extracted from case and control peripheral blood leukocytes were genotyped by pyrosequencing. For candidate polymorphisms, we chose 50 non‐synonymous missense SNPs, which we have previously been identified by resequencing 36 DNA repair genes among the Japanese population. In the first screening, we analyzed 240 cases and 685 controls and selected six SNPs at the significance level of P < 0.1 (Fisher's exact test). The six SNPs were further analyzed in the second genotyping on an additional set of 304 cases and 834 controls. In the joint analysis (the first and second genotyping combined) of 544 cases and 1378 controls, Cys1367Arg of the WRN gene was found to be a protective factor of BSTS (odds ratio = 0.66, 95% confidence interval = 0.49–0.88, P = 0.005). An exploratory subgroup analysis without multiple comparison adjustment suggested that the WRN‐Cys1367Arg SNP is associated with soft tissue sarcomas, sarcomas with reciprocal chromosomal translocations and malignant fibrous histiocytoma. (Cancer Sci 2008; 99: 333–339)

Bone and soft tissue sarcomas (BSTSs) are nonepithelial, non‐hematological malignant tumors of mesenchymal origin. Three characteristics of BSTS are that: (i) they are rare malignancies; (ii) they develop at a variety of sites; any mesenchymal tissues throughout the body; and (iii) show highly heterogeneous histological types. In the United States, the incidence of malignant bone tumors is estimated to be around 0.8 per 100 000 population,( 1 ) and that of soft tissue sarcomas (STS) approximately 5.0 per 100 000.( 2 ) It is estimated that 2370 bone and joint malignancies and 9220 malignant soft tissue tumors would newly develop in 2007.( 3 )

The rarity and the histological heterogeneity of BSTSs have hampered the identification of the risk factors and etiology. BSTSs show a slight male predominance, and the incidence of these rare tumors both in Japan and in other countries seems to be stable in the last several decades except for an increase in Kaposi sarcoma as reported in the United States.( 4 , 5 ) This appears to be in contrast to several other types of cancers, such as gastrointestinal or gynecologic cancers, which have shown a significant change in incidence in Japan probably due to the change in environmental and life style factors. No significant racial variation has been noted in the overall incidence of sarcomas with some exceptions, such as Ewing sarcoma, which reportedly occurs more frequently in Caucasians.( 6 )

To date, some environmental and genetic factors for BSTS risk have been suggested. The environmental factors include external radiation therapy,( 7 ) Thorotrast, arsenical pesticides and medications, phenoxyherbicides, dioxin, vinyl chloride, immunosuppressive drugs, alkylating agents, androgen‐anabolic steroids, human immunodeficiency virus, and human herpes virus type 8.( 5 ) Information on the genetic factors has so far been limited to certain monogenic hereditary cancer syndromes known to be associated with the incidence of BSTS, such as Li–Fraumeni syndrome, hereditary retinoblastoma, and Werner syndrome with a germline mutation of TP53, RB1, and WRN, respectively. These genes are involved in DNA repair and related systems. Other monogenic hereditary syndromes are also associated with the specific type of multiple benign tumors and their malignant transformation, such as multiple neurofibromas and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors in neurofibromatosis 1, and multiple osteochondromas and chondrosarcomas in hereditary multiple exostosis, that have a germline mutation of NF1 and EXT1/2, respectively.

Recently, BSTSs have been considered to be divided into two distinct entities based on their somatic genetic aberrations. One group is characterized by reciprocal chromosome translocations resulting in tumor‐specific fusion genes, which may be a critical step for pathogenesis. Another group of sarcomas tend to show complex abnormalities in the karyotypes, suggesting an overall increase in genetic and chromosomal instability. However, the precise mechanisms of tumorigenesis in both groups remain unclear.

The characteristic increase in the risk of BSTS in inherited diseases caused by germline mutations in the DNA repair and related systems has prompted us to investigate the association of the DNA repair gene polymorphisms with the risk of BSTSs. A case‐control study was carried out on 544 cases with BSTS and 1378 controls at 50 non‐synonymous coding single nucleotide polymorphisms (cSNPs), which we have identified by resequencing of 36 candidate genes on a Japanese population( 8 ). Associated studies of common polymorphisms of the DNA repair genes have already been reported in many types of cancer,( 9 ) but to our knowledge, this study is the first report on BSTS.

Materials and Methods

Study design, case and control subjects. Genotype data of the 50 SNPs,( 8 ) in Table 1 from 240 cases and 685 controls were analyzed as the first screening to select those SNPs to be subjected to the second genotyping in the additional 304 cases and 834 controls. In this study, we used a joint analysis,( 10 ) in which the results of the second genotyping were combined with those of the first genotyping (Table 2).

Table 1.

Fifty missense single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in DNA repair genes grouped by their representative pathways

| DNA repair gene | Gene name | SNP | Amino acid change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base excision repair | |||

| PARP‐1/ADPRT1 | Poly (ADP‐ribose) polymerase family, member 1 | T2444C | Val762Ala |

| A2978G | Lys940Arg | ||

| APE1/APEX | APEX nuclease (multifunctional DNA repair enzyme) 1 | A395G | Ile64Val |

| T649G | Asp148Glu | ||

| MBD4 | Methyl‐CpG binding domain protein 4 | G1212A | Glu346Lys |

| NUDT1 | Nudix (nucleoside diphosphate linked moiety X)‐type motif 1 | G273A | Val83Met |

| OGG1 | 8‐oxoguanine DNA glycosylase | C2243G | Ser326Cys |

| XRCC1 | X‐ray repair complementing defective repair in Chinese hamster cells 1 | C685T | Arg194Trp |

| G944A | Arg280His | ||

| G1301A | Arg399Gln | ||

| Nucleotide excision repair | |||

| ERCC5/XPG | Excision repair cross‐complementing rodent repair deficiency, complementation group 5 | C3507G | His1104Asp |

| ERCC6/CSB | Excision repair cross‐complementing rodent repair deficiency, complementation group 6 | G1275A | Gly399Asp |

| XPC | Xeroderma pigmentosum, complementation group C | A2655C | Lys822Gln |

| XPD/ERCC2 | Excision repair cross‐complementing rodent repair deficiency, complementation group 2 | G1615A | Asp312Asn |

| A2932C | Lys751Gln | ||

| Mismatch repair | |||

| MLH1 | mutL homolog 1, colon cancer, non‐polyposis type 2 | A676G | Ile219Val |

| MLH3 | mutL homolog 3 (Escherichia coli) | C2645T | Pro844Leu |

| C2939T | Thr942Ile | ||

| MSH2 | mutS homolog 2 (E. coli) | C91T | Thr8Met |

| MSH3 | mutS homolog 3 (E. coli) | A3122G | Thr1036Ala |

| MSH6 | mutS homolog 6 (E. coli) | G203A | Gly39Glu |

| DNA damage response genes | |||

| TP53 | Tumor protein p53 (Li–Fraumeni syndrome) | G466C | Arg72Pro |

| DNA double strand break repair | |||

| BLM | Bloom syndrome | C967T | Thr298Met |

| G4035A | Val1321Ile | ||

| BRCA2 | Breast cancer 2, early onset | A1342C | Asn372His |

| KIAA0086 | DNA cross‐link repair 1A | C1867G | His317Asp |

| LIG4 | DNA ligase IV | A2245G | Ile591Val |

| NBS1 | Nijmegen breakage syndrome 1 | G605C | Glu185Gln |

| RAD51L3 | RAD51‐like 3 (S. cerevisiae) | G501A | Arg126Gln |

| RAD54L | RAD54‐like (S. cerevisiae) | A551G | Lys151Glu |

| RINT1 | RAD50 interactor 1 | G33C | Glu4Gln |

| WRN | Werner syndrome | C2573T | Thr781Ile |

| T4330C | Cys1367Arg | ||

| XRCC3 | X‐ray repair complementing defective repair in Chinese hamster cells 3 | C1075T | Thr241Met |

| DNA polymerase | |||

| POLD1 | Polymerase (DNA directed), delta 1 | G409A | Arg119His |

| POLH/XPV/RAD30 | Polymerase (DNA directed), eta | A1840G | Lys535Glu |

| POLI/RAD30B | Polymerase (DNA directed) iota | A2180G | Thr706Ala |

| POLL | Polymerase (DNA directed), lambda | C1683T | Arg438Trp |

| POLZ/REV3 | REV3‐like, catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase zeta (yeast) | C4259T | Thr1146Ile |

| REV1 | REV1 homolog (S. cerevisiae) | T982C | Phe257Ser |

| A1330G | Asn373Ser | ||

| Other pathways | |||

| FANCA | Fanconi anemia, complementation group A | G827A | Ala266Thr |

| G1080A | Arg350Gln | ||

| A1532G | Ser501Gly | ||

| A2457G | Asp809Gly | ||

| C3294T | Ser1088Phe | ||

| FANCE | Fanconi anemia, complementation group E | G451T | Arg89Leu |

| G1213A | Arg343Gln | ||

| FANCF | Fanconi anemia, complementation group F | A983G | Lys324Glu |

| FANCG/XRCC9 | Fanconi anemia, complementation group G | C1382T | Thr297Ile |

ADP, adenosine diphosphate;

Table 2.

Case and control subjects

| 1st screening | 2nd genotyping | Joint analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | Case | Control | Case | Control | ||

| Gender | Male | 143 | 483 | 174 | 492 | 317 | 875 |

| Female | 97 | 202 | 130 | 342 | 227 | 503 | |

| Age | <40 | 109 | 113 | 127 | 214 | 236 | 318 |

| ≥40 | 131 | 572 | 177 | 620 | 308 | 1060 | |

| Institutions † | NCCH | 240 | 242 | 127 | 367 | 242 | |

| NCCE | 19 | 19 | |||||

| KEIO | 302 | 158 | 507 | 158 | 809 | ||

| IWT | 327 | 327 | |||||

| NNH | 141 | ||||||

| Total | 240 | 685 † | 304 | 834 | 544 | 1378 ‡ | |

Distributions of gender, age and five institutions where case and/or control subjects were recruited are listed. †The 685 controls in the first screening are from our published data (8). ‡The 141 NNH control data were not available for the joint analysis. KEIO, Keio University Hospital, Tokyo; IWT, Iwata Hospital, Shizuoka; NCCE, National Cancer Center East, Chiba; NCCH, National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo; NNH, National Nishigunma Hospital, Gunma.

The cases were recruited in three hospitals (National Cancer Center Hospital [NCCH], Tokyo, National Cancer Center East Hospital, Chiba [NCCE], and Keio University Hospital, Tokyo [KEIO]) from January 2004 to March 2005 (Table 2). The patients, all Japanese, were either newly diagnosed as BSTS or had been followed up in an outpatient clinic for the history of BSTS. The cases consisted of various histological subtypes, which were confirmed by histological examination in each hospital (Table 3).

Table 3.

Histological distribution of the cases and subgroup classification

| Bone sarcoma | Soft tissue sarcoma | Subgroup | Total (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteosarcoma | 105 | Liposarcoma | 111 | ALL | 544 (100.0) |

| Chondrosarcoma | 41 | MFH | 92 | BS/STS | |

| EWS/PNET | 18 | Synovial sarcoma | 38 | BS | 190 (34.9) |

| MFH | 11 | Leiomyosarcoma | 19 | STS | 354 (65.1) |

| Chordoma | 8 | MPNST | 19 | Translocation | |

| Adamantinoma | 3 | Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberance | 17 | (+) | 154 (28.3) |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 2 | EWS/PNET | 15 | (–) | 390 (71.7) |

| MPNST | 1 | EMC | 7 | Histopathology | |

| Fibrosarcoma | 1 | Osteosarcoma | 6 | Osteosarcoma | 111 (20.4) |

| 190 | Fibrosarcoma | 5 | MFH | 103 (18.9) | |

| Epithelioid sarcoma | 5 | Liposarcoma | 111 (20.4) | ||

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 6 | Others | 219 (40.3) | ||

| Angiosarcoma | 6 | ||||

| Alveolar soft part sarcoma | 4 | ||||

| Clear cell sarcoma | 2 | ||||

| Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma | 1 | ||||

| Hemangiopericytoma | 1 | ||||

| 354 | |||||

ALL, all samples; BS, bone sarcomas; EMC, extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma; EWS/PNET, Ewing sarcoma and peripheral neuroectodermal tumor; MFH, malignant fibrous histiocytoma; MPNST, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor; STS, soft tissue sarcomas; Translocation (+), sarcomas with reciprocal chromosomal translocations; Translocation (–), sarcomas without reciprocal chromosomal translocations.

We used 685 control subjects in the first screening, which were the same control population as those used in our previous study on the same set of SNPs but on a different type of malignancy, lung cancer (Table 2).( 8 ) Those subjects consisted of 383 non‐cancer patients in two hospitals (NCCH and National Nishigunma Hospital, Gunma [NNH] in Table 2) and 302 healthy volunteers in KEIO (Table 2). We did not, however, include the 141 control subjects from NNH (Table 2) in the subsequent joint analysis, because their individual genotyping data have not been published and are unavailable for analyses other than the lung cancer study. In the second genotyping, we analyzed additional samples from 834 people who participated in the health examination programs (KEIO and Iwata Hospital, Shizuoka [IWT] in Table 2). We consider that these subjects were suitable enough as controls for our cases; most of the control subjects in this study were also analyzed in our separate gastric cancer project involving a SNP‐based genome scan, and its data suggested little if any population stratification (unpublished data, 2007). Therefore, the control subjects for the joint analysis totaled 1378 people with a criterion of no history of cancer during the study period (Table 2).

Subgroup analysis was carried out on the subgroups defined by Table 3. For the ‘sarcomas with reciprocal chromosomal translocations’, we included synovial sarcoma, Ewing sarcoma/peripheral neuroectodermal tumor, myxoid/round cell liposarcoma, clear cell sarcoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberance, extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma, and alveolar soft part sarcoma. The specific fusion genes have been reported for those sarcomas, and cytogenetic examinations are routine for their histological diagnosis.( 11 )

This study was approved by Institutional Review Board of each institution, and all of the subjects signed an informed consent form to participate in the study.

DNA extraction and genotyping. From each individual we obtained a 10–20‐mL sample of whole blood. Genomic DNAs were isolated directly from the samples using Blood Maxi Kit (Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan) or FlexiGene DNA Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Ten nanograms of genomic DNA were subjected to genotyping for 50 SNPs by pyrosequencing using the PSQ96 system (Pyrosequencing, Uppsala, Sweden) as described previously.( 12 ) Briefly, a genomic fragment containing an SNP site was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with a set of PCR primers, one of which was biotinylated. The PCR products were purified using streptavidin‐modified paramagnetic beads (Dynabeads M‐280; Dynal, Skoyen, Norway), denatured and subjected to nucleotide sequencing by pyrosequencing chemistry. Quality of the SNP typing was confirmed by inspection of the sequence data and by Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) tests.

Statistical analysis. Fisher's exact test, odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to analyze association of the SNPs and BSTS risk in allele, dominant (i.e. aa + aA vs AA, where ‘A’ is major allele and ‘a’ is minor allele) and recessive (i.e. aa vs aA + AA) models.( 13 ) Crude OR was used for the allele model, while the dominant and recessive models were analyzed using OR adjusted for age (≥40 vs <40, see Suppl. Fig. S1 online) and gender with 95% CI calculated using a logistic regression analysis. When statistical calculation is not applicable due to 0 subjects being in a cell of a contingency table, we indicate the result as ‘NA’.

In order to identify disease‐associated SNPs, the following criteria were used: candidate SNPs were selected by P‐value < 0.10 on the allele model in the first screening, and then disease associated‐SNPs were statistically identified by the allele model in the joint analysis with a multiple comparison adjustment using the Holm's method,( 14 ) for six SNPs. Please note that the family wise error rate may be inflated by a few percent, depending on the number of the true SNPs present in the initial 50 SNPs, by this method of multiple comparison adjustment, because the first and second screenings are not independent in the joint analysis (see Suppl. Table S1 online).

A subgroup analysis was carried out as an exploratory, adjunct analysis without multiple comparison adjustment to address the histological heterogeneity of BSTS. Because the subgroups showed different age preferences, dominant and recessive models were used in order to adjust age and gender by multiple logistic regression.

Results

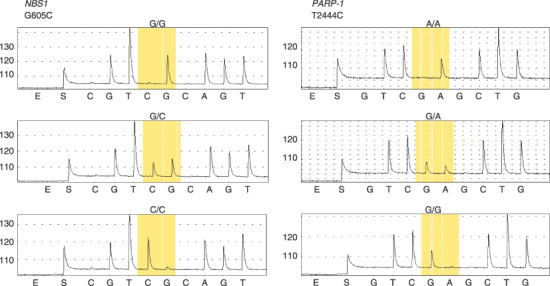

Results of the joint analysis. The typical pyrosequencing data are shown in Fig. 1, and the results of the two‐stage genotyping are summarized in Table 4. Minor allele frequencies and P‐values of the HWE tests are also listed in Table 4. The six SNPs were selected by the first screening, and the final statistical gene selection was made using all the samples genotyped in the first screening and the second genotyping combined, except 141 controls from Nishigunma Hospital (cases = 544 and controls = 1378 in total). We identified a SNP, WRN‐Cys1367Arg, whose allele frequency was significantly different between all BSTS cases and the control subjects (OR = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.49–0.88, P = 0.005 and P = 0.03, before and after six‐SNP multiple comparison adjustment by Holm's method, respectively), showing a protective effect. The minor allele frequency of the SNP is 8.2%.

Figure 1.

Genotyping by pyrosequencing. (a) NBS1‐Glu185Gln (G605C) and (b) PARP‐1‐Val762Ala (T2444C) (sequencing in reverse direction). Top, major homozygote; middle, heterozygote; and bottom, minor homozygote.

Table 4.

Statistics of allele model analysis for the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) selected in the first screening by P < 0.1

| Gene | SNP | Minor allele frequency | HWE (P‐value) | OR | Allele model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n) | Controls (n) | Cases | Controls | 95% CI | P‐value | ||||

| MBD4 | G1212A | 1st screening | 0.304 (240) | 0.349 (685) | 0.545 | 0.207 | 0.82 | 0.65–1.02 | 0.083 |

| Glu346Lys | Joint analysis | 0.335 (544) | 0.353 (1378) | 0.620 | 0.199 | 0.92 | 0.79–1.07 | 0.286 | |

| MSH6 | G203A | 1st screening | 0.275 (240) | 0.323 (685) | 0.074 | 0.793 | 0.80 | 0.63–1.00 | 0.057 |

| Gly39Glu | Joint analysis | 0.304 (544) | 0.310 (1378) | 0.434 | 0.621 | 0.97 | 0.84–1.13 | 0.750 | |

| PARP‐1 | A2978G | 1st screening | 0.077 (240) | 0.050 (685) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.58 | 1.04–2.38 | 0.044 |

| Lys940Arg | Joint analysis | 0.066 (544) | 0.052 (1378) | 1.000 | 0.509 | 1.30 | 0.97–1.74 | 0.098 | |

| REV1 | A1330G | 1st screening | 0.023 (240) | 0.043 (685) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.52 | 0.27–1.00 | 0.055 |

| Asn373Ser | Joint analysis | 0.029 (544) | 0.044 (1378) | 0.042 | 0.680 | 0.67 | 0.45–0.99 | 0.049 | |

| WRN | T4330C | 1st screening | 0.056 (240) | 0.090 (685) | 1.000 | 0.480 | 0.61 | 0.40–0.93 | 0.024 |

| Cys1367Arg | Joint analysis | 0.052 (544) | 0.082 (1378) | 0.213 | 0.619 | 0.66 | 0.49–0.88 | 0.005 | |

| XRCC1 | C685T | 1st screening | 0.279 (240) | 0.327 (685) | 0.016 | 1.000 | 0.80 | 0.63–1.00 | 0.058 |

| Arg194Trp | Joint analysis | 0.292 (544) | 0.323 (1378) | 0.587 | 0.811 | 0.87 | 0.74–1.01 | 0.073 | |

CI, confidence interval; HWE, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium; OR, odds ratio.

Subgroup analysis. Since BSTS is characterized by the substantial heterogeneity in its histology, the effects of the DNA repair gene polymorphisms might differ among the subgroups. The results of the subgroup analysis of the WRN‐Cys1367Arg SNP are shown in Table 5. Although under‐powered and exploratory in nature, the subgroup analysis suggested that the difference in genotype frequency of WRN‐Cys1367Arg between the cases and controls appears to be significant in STS, sarcomas with reciprocal chromosomal translocations and malignant fibrous histiocytoma. It is noted, however, that the effect direction of the minor allele (Arg1367) of this SNP was protective in all of the subgroups, except osteosarcoma (OR = 1.00), irrespective of the statistical significance. The subgroup analysis data of the other five SNPs analyzed in the second stage is shown in Suppl. Table S2 online.

Table 5.

Statistics of subgroup analysis using recessive and dominant models

| SNP | Subgroup | (n) | Recessive model † | Dominant model ‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P‐value | OR | 95% CI | P‐value | |||

| WRN | ALL | 544 | 0.43 | 0.09–2.01 | 0.442 | 0.66 | 0.48–0.91 | 0.011 |

| T4330C | BS | 190 | NA | NA–NA | 0.489 | 0.85 | 0.53–1.37 | 0.589 |

| Cys1367Arg | STS | 354 | 0.72 | 0.16–3.32 | 0.998 | 0.58 | 0.40–0.85 | 0.005 |

| Translocation (+) | 154 | NA | NA–NA | 0.632 | 0.52 | 0.29–0.95 | 0.034 | |

| Translocation (–) | 390 | 0.61 | 0.13–2.86 | 0.817 | 0.72 | 0.51–1.02 | 0.068 | |

| Osteosarcoma | 111 | NA | NA–NA | 0.826 | 1.00 | 0.56–1.80 | 1.000 | |

| MFH | 103 | NA | NA–NA | 1.000 | 0.45 | 0.22–0.94 | 0.032 | |

| Liposarcoma | 111 | NA | NA–NA | 0.911 | 0.72 | 0.40–1.31 | 0.346 | |

Odds ratios (OR) adjusted for age (≥ 40, < 40) and gender with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using a logistic regression analysis for all subgroups. Cases = 544 and Controls = 1378 in total. †Recessive model is aa versus aA + AA. ‡Dominant model is aa + aA versus AA, where a is a minor allele. ALL, all samples; BS, bone sarcomas; MFH, malignant fibrous histiocytoma; NA, statistical calculation not applicable, because the number of the subjects is less than five in any cell in a contingency table; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; STS, soft tissue sarcomas; Translocation (+), sarcomas with reciprocal chromosomal translocations; Translocation (–), sarcomas without reciprocal chromosomal translocations.

Discussion

This study attempted the first systematic survey on the possible role of DNA repair gene polymorphisms in the susceptibility to sporadic BSTS. From the joint analysis of the two‐stage case‐control study on total 544 cases with BSTS of various histology and 1378 controls, a missense SNP of the WRN gene, Cys1367Arg, was identified. WRN is a member of the RecQ family of DNA helicases, and mutations of the gene can give rise to a rare autosomal recessive genetic instability disorders, Werner syndrome (WS).( 15 ) WS is a premature aging disease characterized by predisposition to cancer and the early onset of symptoms related to normal aging.( 16 ) The types of cancer with elevated risk appear selective, including soft tissue sarcomas, thyroid carcinoma, malignant melanoma, meningioma, hematological malignancies, and osteosarcoma. A diversity of malignancies was found in WS in the literature from 1939 to 1995, but it is noteworthy that the ratio of epithelial to nonepithelial cancers was about 1:1, instead of the usual 10:1.( 17 ) BSTS make up more than 20% of cancer arising in WS patients.( 17 ) Soft tissue sarcomas that have been identified in WS patients include malignant fibrous histiocytoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, fibrosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, and synovial sarcoma. The reason for the high representation of mesenchymal tumors in WS patients has not been clarified.

WRN encodes a protein with 1432 amino acids that possesses both 3′→5′ DNA helicase and 3′→5′ DNA exonuclease activities. DNA helicases are enzymes that unwind the energetically stable double‐stranded structure of DNA to provide a single‐stranded template for important cellular processes such as replication, base excision repair, homologous recombination, and telomere maintenance.( 15 , 18 , 19 )

Several epidemiological studies have already been carried out on WRN‐Cys1367Arg. Most of those studies focused on the diseases relating to the WS phenotype, such as myocardial infarction, diabetes mellitus and lymphomas. The more frequent Cys1367 allele has been reported to be associated with a lower frequency of osteoporosis in postmenopausal Japanese women,( 20 ) whereas the minor allele Arg1367 may be associated with a lower risk of myocardial infarction and type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Japanese population.( 21 , 22 ) With regard to cancer risk, Arg1367 was reported to be associated with a decreased risk of non‐Hodgkin lymphoma among women in Connecticut.( 23 ) Of note, in three out of the four reports listed above, WRN‐Cys1367Arg showed protective effects against the various diseases associated with WS phenotype, and the same held true for our observations on BSTS.

Based on the observations that all of the pathogenic WRN mutations identified so far result in truncation of the C‐terminal of the WRN protein, it has been proposed that a lack of the C‐terminal nuclear localization signal is important in the pathogenesis of WS.( 24 , 25 ) Although WRN‐Cys1367Arg is located adjacent to the nuclear localization signal, a previous report has failed to detect any significant difference between WRN (Arg1367) and WRN (Cys1367) with respect to their nuclear localization,( 26 ) or helicase and helicase‐coupled exonuclease activity.( 27 ) Other possible explanations for the observed association include the allelic difference of WRN‐Cys1367Arg in the interactions with other proteins or the presence of unknown functionally responsible polymorphisms that are in linkage disequilibrium with WRN‐Cys1367Arg.

Some of the SNPs on the genes responsible for a hereditary form of cancer have shown association with a sporadic form of the same type of cancer.( 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ) Our findings on the WRN SNP on BSTS may add another example of the possible sharing, at least in part, of the oncogenesis pathway between the monogenic and polygenic forms of the same type of cancer and a continuity of the genotype‐phenotype spectrum.

It may be controversial to analyze the possible genetic backgrounds with all types of BSTS combined because of its highly heterogeneous nature in histology. However, little if any information is currently available on the genetic predisposition to the sporadic forms of BSTS, and genetic factors that are common to most BSTSs may exist, as well as those specific to certain subgroups. As one of the first exploratory analyses on the genetic susceptibility of sporadic BSTS, the primary role of this study is to generate hypotheses, which deserve further validation. To validate the hypothesis, evidence should be sought both in statistical replication and meta‐analysis using future case‐control panels and also in biological functional analyses.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Matsuhiko Hayashi and Dr Yoichi Ohno of Department of Internal Medicine, Keio University School of Medicine, and Dr Fumihiko Tanioka of Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Iwata Municipal General Hospital for their help in collecting blood samples, and Ms. Sachiyo Mimaki and Mr Hirohiko Totsuka of the Center for Medical Genomics, National Cancer Center for providing considerable contributions to DNA sequencing and statistical analysis. This study was supported by the program for promotion of Fundamental Studies in Health Sciences of the National Institute of Biomedical Innovation (NiBio) and in part by Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Area (18014009) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

References

- 1. Dorfman HD, Czerniak B. Bone cancers. Cancer 1995; 75: 203–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Toro JR, Travis LB, Wu HJ, Zhu K, Fletcher CD, Devesa SS. Incidence patterns of soft tissue sarcomas, regardless of primary site, in the surveillance, epidemiology and end results program, 1978–2001: an analysis of 26 758 cases. Int J Cancer 2006; 119: 2922–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin 2007; 57: 43–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ross JA, Severson RK, Davis S, Brooks JJ. Trends in the incidence of soft tissue sarcomas in the United States from 1973 through 1987. Cancer 1993; 72: 486–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zahm SH, Fraumeni JF Jr. The epidemiology of soft tissue sarcoma. Semin Oncol 1997; 24: 504–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Polednak AP. Primary bone cancer incidence in black and white residents of New York State. Cancer 1985; 55: 2883–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mark RJ, Poen J, Tran LM, Fu YS, Selch MT, Parker RG. Postirradiation sarcomas. A single‐institution study and review of the literature. Cancer 1994; 73: 2653–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sakiyama T, Kohno T, Mimaki S et al . Association of amino acid substitution polymorphisms in DNA repair genes TP53, POLI, REV1 and LIG4 with lung cancer risk. Int J Cancer 2005; 114: 730–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goode EL, Ulrich CM, Potter JD. Polymorphisms in DNA repair genes and associations with cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2002; 11: 1513–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Skol AD, Scott LJ, Abecasis GR, Boehnke M. Joint analysis is more efficient than replication‐based analysis for two‐stage genome‐wide association studies. Nat Genet 2006; 38: 209–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sandberg AA. Cytogenetics and molecular genetics of bone and soft‐tissue tumors. Am J Med Genet 2002; 115: 189–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alderborn A, Kristofferson A, Hammerling U. Determination of single‐nucleotide polymorphisms by real‐time pyrophosphate DNA sequencing. Genome Res 2000; 10: 1249–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical methods in cancer research. Vol. I. – the analysis of case‐control studies. IARC Sci Pub 1980: 5–338. [PubMed]

- 14. Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Statistics 1979; 6: 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yu CE, Oshima J, Fu YH et al . Positional cloning of the Werner's syndrome gene. Science 1996; 272: 258–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Epstein CJ, Martin GM, Schultz AL, Motulsky AG. Werner's syndrome a review of its symptomatology, natural history, pathologic features, genetics and relationship to the natural aging process. Medicine (Baltimore) 1966; 45: 177–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goto M, Miller RW, Ishikawa Y, Sugano H. Excess of rare cancers in Werner syndrome (adult progeria). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1996; 5: 239–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gray MD, Shen JC, Kamath‐Loeb AS et al . The Werner syndrome protein is a DNA helicase. Nat Genet 1997; 17: 100–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kamath‐Loeb AS, Shen JC, Loeb LA, Fry M. Werner syndrome protein. II. Characterization of the integral 3′→5′ DNA exonuclease. J Biol Chem 1998; 273: 34 145–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ogata N, Shiraki M, Hosoi T, Koshizuka Y, Nakamura K, Kawaguchi H. A polymorphic variant at the Werner helicase (WRN) gene is associated with bone density, but not spondylosis, in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Metab 2001; 19: 296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ye L, Miki T, Nakura J, Oshima J et al . Association of a polymorphic variant of the Werner helicase gene with myocardial infarction in a Japanese population. Am J Med Genet 1997; 68: 494–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hirai M, Suzuki S, Hinokio Y et al . WRN gene 1367 Arg allele protects against development of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2005; 69: 287–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shen M, Zheng T, Lan Q et al . Polymorphisms in DNA repair genes and risk of non‐Hodgkin lymphoma among women in Connecticut. Hum Genet 2006; 119: 659–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matsumoto T, Shimamoto A, Goto M, Furuichi Y. Impaired nuclear localization of defective DNA helicases in Werner's syndrome. Nat Genet 1997; 16: 335–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yu CE, Oshima J, Wijsman EM et al . Mutations in the consensus helicase domains of the Werner syndrome gene. Werner's Syndrome Collaborative Group. Am J Hum Genet 1997; 60: 330–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bohr VA, Metter EJ, Harrigan JA et al . Werner syndrome protein 1367 variants and disposition towards coronary artery disease in Caucasian patients. Mech Ageing Dev 2004; 125: 491–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kamath‐Loeb AS, Welcsh P, Waite M, Adman ET, Loeb LA. The enzymatic activities of the Werner syndrome protein are disabled by the amino acid polymorphism R834C. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 55 499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Healey CS, Dunning AM, Teare MD et al . A common variant in BRCA2 is associated with both breast cancer risk and prenatal viability. Nat Genet 2000; 26: 362–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Slattery ML, Samowitz W, Ballard L, Schaffer D, Leppert M, Potter JD. A molecular variant of the APC gene at codon 1822: its association with diet, lifestyle, and risk of colon cancer. Cancer Res 2001; 61: 1000–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Freedman ML, Penney KL, Stram DO, Le Marchand L et al . Common variation in BRCA2 and breast cancer risk: a haplotype‐based analysis in the Multiethnic Cohort. Hum Mol Genet 2004; 13: 2431–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Freedman ML, Penney KL, Stram DO et al . A haplotype‐based case‐control study of BRCA1 and sporadic breast cancer risk. Cancer Res 2005; 65: 7516–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]