Abstract

Rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone (R‐CHOP) is one of the most frequently applied initial treatments for indolent B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma (B‐NHL); however, information on its long‐term outcome is limited. Untreated patients in the concurrent arm (Arm C) received six R (375 mg/m2) treatments, 2 days prior to each cycle of CHOP, and patients in the sequential arm (Arm S) received 6 weekly R (375 mg/m2) treatments following six cycles of CHOP. Sixty‐nine patients were randomized but two patients were withdrawn before receiving the protocol treatment. Sixty‐five patients (94%) had follicular lymphoma, and 37 (55%) were at low risk, 23 (34%) at intermediate risk and seven (10%) at high risk according to the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index. We previously reported that the overall response rate (ORR) in Arm C and in Arm S was 94% and 97%, respectively. The median progression‐free survival (PFS)/7‐year PFS rate in Arm C, Arm S and all 67 assessable patients was 2.4 years/23% (95% confidence interval [CI], 9–40%), 3.8 years/41% (95% CI, 23–57%) and 2.8 years/32% (95% CI, 20–45%), respectively. There was no significant difference between the two arms (P = 0.107). The overall survival (OS) of the 67 patients was 95% at 7 years. In conclusion, R‐CHOP is a highly effective initial treatment for untreated indolent B‐NHL in terms of ORR and OS; however, its long‐term PFS is not good enough either in concurrent or sequential combination, warranting further investigations on post‐remission therapy. (Cancer Sci 2010; 101: 2579–2585)

Since the introduction of a chimeric anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody, rituximab, into the treatment of B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma (B‐NHL),( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ) various clinical trials have been carried out to investigate the efficacy of its combination with conventional chemotherapies, and currently, the combination of rituximab with chemotherapy is regarded as a routine modality for the treatment of B‐NHL.( 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ) Rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone (R‐CHOP) has been regarded as the gold standard for the treatment of diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma.( 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 )

Indolent B‐NHL, of which the representative histopathological subtype is follicular lymphoma, is characterized by an advanced stage at presentation, lack of symptoms, indolent behavior and a long natural history in most patients. Various treatment strategies, including a watch and wait policy until progression,( 13 , 14 , 15 ) cytotoxic chemotherapy with a single agent or in combination,( 6 , 14 , 15 , 16 ) antibody therapy( 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ) and stem cell transplantation( 21 ) have been tested; however, the majority of patients remain incurable, and no standard therapy has been established.( 7 , 22 ) In 1999, Czuczman et al. reported the initial results of the first phase II study of R‐CHOP in mostly untreated patients with indolent B‐NHL, showing a high overall response rate (ORR) of 95% (38/40).( 23 ) Currently, R‐CHOP is one of the most frequently applied chemotherapeutic regimens for the treatment of untreated indolent B‐NHL.( 24 )

In 1999, we initiated a multicenter, randomized phase II study to compare CHOP combined with rituximab concurrently or sequentially in previously untreated indolent B‐NHL of advanced stage. The primary objective of the study was to select a promising combination regimen for further investigation in view of ORR as the primary end‐point. Our initial analysis at a median follow‐up time of 28.2 months demonstrated that both arms were equally highly effective, with 94% or higher ORR, including almost 70% complete response (CR) with acceptable toxicities. Thus, we concluded that R‐CHOP is highly effective for untreated indolent B‐NHL, either concurrently or in sequential combination, and that both combination schedules deserve further investigation.( 25 )

Several randomized studies have suggested the advantage of R‐CHOP over CHOP alone in the treatment of follicular or indolent B‐NHL.( 26 , 27 ) However, the majority of studies investigating R‐CHOP were carried out by combining rituximab concurrently with CHOP, and studies on CHOP followed by rituximab or other combination schedules are limited.( 6 , 28 ) More importantly, long‐term follow‐up results after rituximab‐containing chemotherapy for indolent B‐NHL have not been sufficiently elucidated, except for the US phase II study of R‐CHOP( 23 , 29 ) and the European phase III study of rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone (R‐CVP) versus CVP alone.( 30 ) In the former US phase II study reporting 9‐year follow‐up results, the authors claimed prolonged clinical and molecular remission, with time to progression (TTP) of 82.3 months; however, this single‐arm phase II study has several limitations, including a small sample number, unusual combination schedule and heterogeneous populations.( 29 ) In the latter European phase III study of a fairly large number of patients (n = 321), the chemotherapeutic regimen is not CHOP but CVP.( 30 ) Thus, information regarding the long‐term therapeutic outcome after R‐CHOP for indolent B‐NHL is still quite limited. From the viewpoints described above, this 7‐year follow‐up study provides additional information regarding the response durability of R‐CHOP for untreated indolent B‐NHL.

Patients and methods

This long‐term follow‐up study with a median follow‐up time of 7.1 years regarding progression‐free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) is an update of a Japanese phase II, open‐label, multicenter, randomized study. Detailed descriptions of the study design and the initial results after the induction phase have been reported previously.( 25 ) Briefly, untreated patients diagnosed as having indolent B‐NHL of advanced stage, exclusive of mantle cell lymphoma, were randomized to either the concurrent arm (Arm C), where rituximab 375 mg/m2 was given 2 days prior to each cycle of CHOP in six cycles, or the sequential arm (Arm S), where rituximab 375 mg/m2 was given six times weekly following six cycles of CHOP. Sixty‐nine patients were enrolled, and the primary end‐point of ORR was 94% (30/32; 95% confidence interval [CI], 79–99%) for Arm C and 97% (33/34; 95%CI, 85–100%) for Arm S.( 25 )

As described in our previous manuscript, approval was obtained from the institutional review boards of all participating institutions. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrollment in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.( 25 ) Participating institutions and principal investigators of the IDEC‐C2B8 Study Group are shown in the Appendix.

In this 7‐year follow‐up study, of the 69 patients enrolled, two patients who had never received the protocol treatment were removed from analyses. The remaining 67 patients who had received the allocated arm treatment were included in the analytical data set. The International Workshop Response Criteria for NHL published in 1999 was applied to evaluate the tumor response.( 31 ) Tumor progression was monitored at approximately 3‐month intervals for the first 12 months, and every 4–6 months thereafter until lymphoma progression or for 7 years.

Adverse events (AE) of the delayed type were also monitored for 7 years or at least until lymphoma progression, and were graded according to the toxicity criteria of the Japan Clinical Oncology Group,( 32 ) an expanded version of the Common Toxicity Criteria version 1.0 by the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD, USA).

The PFS data for patients who were transferred to other institutions were censored on the last date of assessment. Survival information for patients who were transferred to other institutions was obtained by questionnaire addressed to the hospital doctor in charge. The PFS and OS were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the log‐rank test was carried out to examine differences between cohorts. Statistical Analysis System (SAS, Cary, NC, USA), version 9.1, was used for analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics. Sixty‐seven patients who received either Arm C (n = 34) or Arm S (n = 33) were evaluated. The majority of patients had follicular lymphoma (FL) accounting for 96% (64 patients) of the 67 assessable patients revealed by the central pathology review.( 25 ) The allocated protocol treatment was not completed in two of the 67 patients due to grade 3 AE. One had cholangitis after the third cycle of R‐CHOP in Arm C, and the other had interstitial pneumonia after the third cycle of CHOP in Arm S. The protocol treatment was completed in the remaining 65 patients. Patient characteristics at entry are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Factors | Enrolled | Evaluated | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arm C (n = 34) | Arm S (n = 35) | Total (n = 69) | Arm C (n = 34) | Arm S (n = 33) | Total (n = 67)† | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 18 | 18 | 36 | 18 | 17 | 35 |

| Male | 16 | 17 | 33 | 16 | 16 | 32 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| Median | 53 | 50 | 52 | 53 | 49 | 52 |

| Range | 36–65 | 26–69 | 26–69 | 36–65 | 26–69 | 26–69 |

| Performance status (ECOG) | ||||||

| 0 | 29 | 30 | 59 | 29 | 28 | 57 |

| 1 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| Histopathology (REAL)‡ | ||||||

| Follicular, grade 1 | 12 | 11 | 23 | 12 | 11 | 23 |

| Follicular, grade 2 | 21 | 19 | 40 | 21 | 18 | 39 |

| Follicular, grade 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Marginal zone | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Low‐grade B‐NHL, NOS§ | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| No specimen¶ | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Clinical stage (Ann Arbor) | ||||||

| III | 14 | 15 | 29 | 14 | 13 | 27 |

| IV | 20 | 20 | 40 | 20 | 20 | 40 |

| B symptoms | ||||||

| Absent | 30 | 33 | 63 | 30 | 31 | 61 |

| Present | 4 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| LDH | ||||||

| Normal | 32 | 31 | 63 | 32 | 29 | 61 |

| Elevated | 2 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Number of extranodal sites | ||||||

| 0 or 1 | 25 | 26 | 51 | 25 | 24 | 49 |

| 2 or more | 9 | 9 | 18 | 9 | 9 | 18 |

| International prognostic index | ||||||

| Low | 21 | 21 | 42 | 21 | 19 | 40 |

| Low‐intermediate | 12 | 12 | 24 | 12 | 12 | 24 |

| High‐intermediate | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| High | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index | ||||||

| Low | 18 | 20 | 38 | 18 | 19 | 37 |

| Intermediate | 13 | 11 | 24 | 13 | 10 | 23 |

| High | 3 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 7 |

Arm C, concurrent arm; Arm S, sequential arm; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; REAL, revised European–American classification of lymphoid neoplasms. †Two patients who withdrew before the protocol treatment initiation with the allocated arm were removed from evaluation. ‡According to the diagnosis by the Central Pathology Review Committee. §Low‐grade B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma (B‐NHL), not otherwise specified (NOS). ¶Specimen for central pathology review was not submitted.

Of the 67 patients evaluated, two patients were judged “ineligible” for ORR analysis at the induction phase: one patient was ineligible due to concomitant kidney cancer, and his follow up was censored at his last observation; and the other patient was ineligible due to a prior history of anthracycline use for breast cancer, which was recognized after completion of the protocol treatment, and her lymphoma progression had been confirmed before judging her ineligibility. In addition, one patient who received erroneous protocol treatment was included in this long‐term follow‐up analysis, that is, a patient who erroneously received daunorubicin (50 mg/m2) instead of doxorubicin in the first cycle of CHOP.

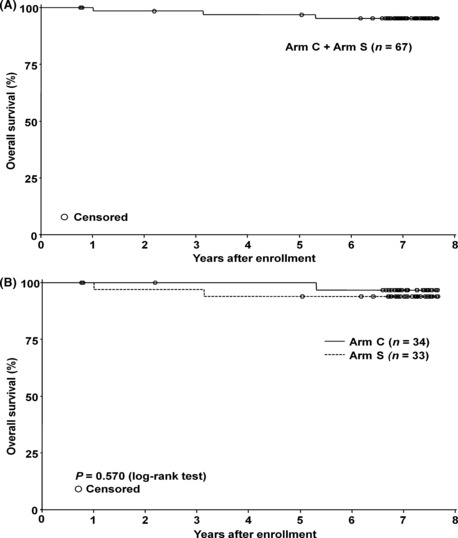

Progression‐free survival. All 67 patients who received the protocol treatment were followed up for 7 years or until lymphoma progression, and their PFS and OS were updated. Fourteen patients (Arm C, five patients; Arm S, nine patients) were followed up until 7 years without progression. Kaplan–Meier plots of the PFS for all 67 patients (Arm C + Arm S) and for each treatment arm are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Progression‐free survival (PFS). (A) The PFS of 67 assessable patients. Median PFS with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was estimated to be 2.8 years with a 95% CI of 2.1–4.4 years. (B) The PFS by the treatment arm. Median PFS with the 95% CI of the concurrent arm (Arm C) (n = 34) and the sequential arm (Arm S) (n = 33) were estimated to be 2.4 years with a 95% CI of 1.9–3.4 years, and 3.8 years with a 95% CI of 2.1– years, respectively. There was no statistical difference between the two arms using log‐rank test (P = 0.107).

As shown in Table 2, the median PFS of Arm C, Arm S and all 67 patients was 2.4, 3.8 and 2.8 years, respectively; the 7‐year PFS rate of Arm C, Arm S and all 67 patients was 23%, 41% and 32%, respectively. There was no significant difference between the two arms (P = 0.107, log‐rank test).

Table 2.

Progression‐free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) by treatment arm

| Cohort | n | Median PFS (years) | 7‐year PFS (%) | 7‐year OS (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | |||||

| Arm C† | 34 | 2.4 | 1.9–3.4 | 23 | 9–40 | 97 | 79–100 |

| Arm S‡ | 33 | 3.8 | 2.1– | 41 | 23–57 | 94 | 78–98 |

| ALL (Arm C + S) § | 67 | 2.8 | 2.1–4.4 | 32 | 20–45 | 95 | 86–98 |

There was no statistical difference between Arm C and Arm S in the progression‐free survival (P = 0.1071 by log‐rank test). CI, confidence interval. Tumor progression was evaluated according to the International Workshop Response Criteria for Non‐Hodgkin Lymphoma, at approximately 3‐month intervals for the first 12 months and every 4–6 months thereafter. †Patient group treated with rituximab plus CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone) concurrently 2 days prior to each CHOP cycle, repeating six cycles every 3 weeks. ‡Patient group treated with six cycles of CHOP repeated every 3 weeks, followed by rituximab given six times weekly. §All 67 patients were treated with either the concurrent arm (Arm C) or the sequential arm (Arm S) in this study.

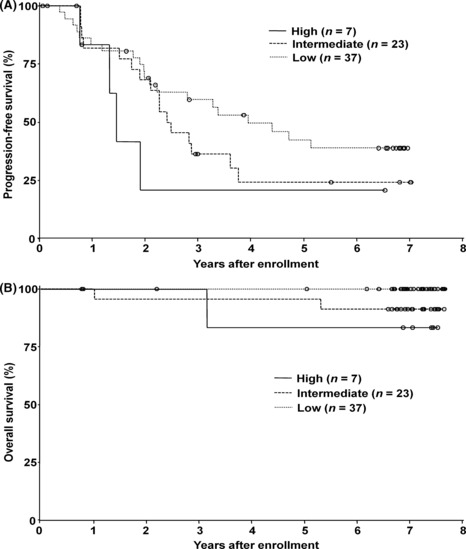

Overall survival. Kaplan–Meier plots of OS for the 67 patients and for each arm are shown in Figure 2. Three patients died from lymphoma progression during the 7‐year follow up. Fifty‐eight patients were confirmed to have survived for 7 years. However, for the remaining six patients, complete survival information could not be obtained because of a change of abode as well as institution. The estimated 7‐year OS rate for Arm C, Arm S and all 67 patients was 97%, 94% and 95%, respectively, as shown in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Overall survival (OS). (A) The OS of the 67 assessable patients. The 7‐year OS rate with 95% confidence interval (CI) was estimated to be 95% with a 95% CI of 86–98%. (B) The OS by the treatment arm. The 7‐year OS rate with a 95% CI of the concurrent arm (Arm C) (n = 34) and the sequential arm (Arm S) (n = 33) was estimated to be 97% with a 95% CI of 79–100%, and 94% with a 95% CI of 78–98%, respectively. There was no statistical difference between the two arms using log‐rank test (P = 0.570).

PFS and OS by the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI). As 64 (96%) of the 67 patients had follicular lymphoma, PFS curves by FLIPI( 33 ) are shown in Figure 3. The FLIPI scoring was also applied to the remaining three patients diagnosed as having marginal zone B‐cell lymphoma or low‐grade B‐NHL, not otherwise specified. The median PFS for the low‐, intermediate‐ and high‐risk groups was 4.0, 2.5 and 1.5 years, respectively, and the 7‐year PFS for the low‐, intermediate‐ and high‐risk groups was 39%, 24% and 21%, respectively, as shown in Table 3. There were no statistical differences among the low‐, intermediate‐ and high‐risk groups.

Figure 3.

The progression‐free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) according to the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI). (A) The PFS according to the FLIPI risk group. The median PFS with 95% confidence intervals (CI) of low‐risk (n = 37), intermediate‐risk (n = 23) and high‐risk (n = 7) groups was 4.0 years with a 95% CI of 2.2– years, 2.5 years with a 95% CI of 1.9–3.8 years, and 1.5 years with 95% CI of 1.3– years, respectively. (B) The OS according to the FLIPI risk group. The 7‐year OS rate with 95% CI of low‐risk (n = 37), intermediate‐risk (n = 23) and high‐risk (n = 7) groups was 100% with a 95% CI of 100–100%, 91% with a 95% CI of 69–98%, and 83% with a 95% CI of 27–97%, respectively. (O), censored.

Table 3.

Progression‐free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) by the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index

| FLIPI | n | Median PFS (years) | 7‐year PFS (%) | 7‐year OS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | |||||

| Low | 37 | 4.0 | 2.2– | 39 | 22–55 | 100 | 100–100 |

| Intermediate | 23 | 2.5 | 1.9–3.8 | 24 | 8–44 | 91 | 69–98 |

| High | 7 | 1.5 | 1.3– | 21 | 1–60 | 83 | 27–97 |

Tumor progression was evaluated according to the International Workshop Response Criteria for Non‐Hodgkin Lymphoma at approximately 3‐month intervals for the first 12 months and every 4–6 months thereafter. There were no statistical differences among the low‐, intermediate‐ and high‐risk groups. CI, confidence interval; FLIPI, Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index.

Late‐onset adverse events. Clinically significant AE that occurred during the induction phase, that is, from the start of protocol treatment to 6 months after the last cycle of CHOP, were reported in our previous paper.( 25 ) In the present report, we focused on the late onset AE observed during the 7‐year follow up.

All three deaths were associated with lymphoma progression, and no patients died due to AE associated with the protocol treatment. Serious AE were documented in four patients during the follow‐up period: prosthetic aortic valve replacement, cerebral hemorrhage, bodyweight gain and stomach cancer. It is unlikely that these four AE were directly associated with the protocol treatment. Besides, no late‐onset cardiac dysfunctions associated with the R‐CHOP treatment were documented during the follow‐up period.

Discussion

The 7‐year OS of patients with indolent B‐NHL treated with R‐CHOP in the present study was excellent, with 97% for Arm C and 94% for Arm S, which appeared to be closely associated with the excellent ORR by R‐CHOP, with 94% for Arm C and 97% for Arm S;( 25 ) however, the 7‐year PFS is not satisfactory, with 23% for Arm C and 41% for Arm S. More than 50% of patients relapsed within 4 years, and no clear plateau of the PFS curve was observed in either arm. Czuczman et al. reported a somewhat longer TTP of 82.3 months by R‐CHOP alone.( 29 ) The reason for the difference in PFS and TTP between the two studies is unclear, but might be partly explained by the small sample numbers and different background factors, including histopathological subtypes, different administration schedules of rituximab, etc. Although they claimed a long response durability in their 9‐year follow‐up study, more than half of the patients relapsed.( 29 ) Taken together, it appears reasonable to consider that most patients with indolent B‐NHL are still incurable by R‐CHOP alone.

One of the large‐scale clinical trials investigating the efficacy of R‐CHOP for indolent B‐NHL is a German study for untreated follicular lymphoma.( 26 ) According to the updated results at a median 58‐month follow up, the improvement of time to treatment failure (TTF), response duration (RD) and OS remained consistently superior in the R‐CHOP group compared with the CHOP alone group;( 34 ) however, the number of patients free from treatment failure decreased in a linear manner over time, even in the R‐CHOP group. The patients enrolled in the German study were secondarily randomized after remission induced by R‐CHOP, and received post‐remission therapy with interferon alpha maintenance or myeloablative chemoradiotherapy with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. The estimated 5‐year TTF of 65% appears to be longer than the 7‐year PFS of 32% in the present study, possibly suggesting the prolonging remission effect of the post‐remission therapy.

The maintenance use of rituximab is a promising option for prolonging PFS in the treatment of indolent B‐NHL. The results of the Primary Rituximab Maintenance (PRIMA) study, where rituximab was combined concurrently with a CHOP‐like or fludarabine‐containing regimen for induction in untreated follicular lymphoma patients with high tumor burden, and responders were randomized to either maintenance with rituximab given bimonthly for 2 years or observation, are expected to show a prolonging PFS effect in the maintenance rituximab arm, considering several preceding studies suggesting its usefulness in the treatment of indolent B‐NHL, including a German study,( 35 ) European study,( 27 ) US studies( 36 , 37 ) and Swiss study.( 38 )

Another potentially effective strategy for prolonging PFS after R‐CHOP might be radioimmunotherapy. The researchers of the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) in the United States reported a favorable 5‐year PFS rate of 67% in a phase II study of CHOP followed by idodine‐131(131I)‐labeled anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody, tositumomab, for untreated follicular lymphoma patients of advanced stages.( 39 ) The authors claimed that the 5‐year estimate of PFS was 23% better than the corresponding figures for patients treated with previous SWOG protocols with CHOP alone.( 6 , 39 ) Based on the encouraging results of the phase II study, they completed patient enrolment into the subsequent phase III trial comparing R‐CHOP. Another anti‐CD20 radioimmunoconjugate, yttrium‐90 (90Y)‐labeled ibritumomab tiuxetan, was also evaluated for advanced‐stage follicular lymphoma in first remission in an international phase III study.( 40 ) 90Y‐ibritumomab tiuxetan consolidation significantly prolonged median PFS compared with the no consolidation arm (36.5 vs 13.3 months; hazard ratio, 0.465; P < 0.0001). Although this phase III study clearly demonstrated the efficacy of 90Y‐ibritumomab tiuxetan as post‐remission therapy in follicular lymphoma, most enrolled patients (86%, 350/409) had not received rituximab‐containing chemotherapy as the initial treatment. Therefore, to elucidate the exact role of anti‐CD20 radioimmunotherapy as post‐remission therapy after rituximab‐containing chemotherapy like R‐CHOP, prospective comparative studies directly targeting this cohort are needed.

Although the primary end‐point of this randomized phase II study is ORR of R‐CHOP chemotherapy, and survival parameters such as PFS and OS are among the secondary end‐points associated with insufficient statistical power due to small samples, it is noteworthy that the favorable tendency of the sequential combination in the R‐CHOP arm was recognized not only in the initial analysis( 25 ) but also in the 7‐year follow‐up study. The exact reason for this finding is unclear; however, the use of rituximab after reduction of the tumor burden by chemotherapy might be a more promising treatment strategy for prolonging PFS in the treatment of indolent B‐NHL, or antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity might be more active with intact effector cells recovered after the completion of chemotherapy.

As shown in Table 1, according to the International Prognostic Index (IPI), 96% of assessable patients (64/67) were categorized as a low‐ or low‐intermediate‐risk group, and only 4% (3/67) were categorized as a high‐intermediate‐ or high‐risk group. As compared with IPI, FLIPI discriminated the three risk groups (55%, 34% and 10%) in a better‐balanced manner. As shown in Table 3 and Figure 3, a tendency towards the relationship of PFS and OS with the FLIPI risk groups was recognized, although there were no statistical differences, presumably due to the small samples. FLIPI was developed from the data of follicular lymphoma patients who had been treated in the pre‐rituximab era.( 33 ) Thus, the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index 2,( 41 ) which was recently proposed based on the PFS and OS data of follicular lymphoma patients who were treated in the rituximab era, deserves future investigation.

In conclusion, the combination of rituximab with CHOP either concurrently or sequentially is highly effective for remission induction in previously untreated patients with indolent B‐NHL. While the OS was excellent and significant late‐onset AE were not observed, the estimated PFS after 7‐year follow up without post‐remission therapy is not satisfactory either in the concurrent or sequential combination of R‐CHOP. Further investigations on post‐remission therapy after R‐CHOP are warranted.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Zenyaku Kogyo Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan. We thank the patients and their family members, and all the investigators, including the physicians, nurses and laboratory technicians in the participating institutions of this multicenter trial. We are grateful to Drs N. Horikoshi (Juntendo University School of Medicine, Tokyo), K. Oshimi (Juntendo University School of Medicine, Tokyo) and K. Toyama (Tokyo Medical College, Tokyo) for their critical review of the clinical data as members of the Independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee. We are also grateful to Drs S. Nawano (National Cancer Center Hospital East, Kashiwa) and M. Matsusako (St Luke’s International Hospital, Tokyo) for their central radiological review as members of the CT Review Committee. We also acknowledge Messers Y. Arita, T. Uesugi, M. Tachikawa, Y. Ikematsu, T. Itoh, K. Inatomi and T. Kayo (Zenyaku Kogyo Co.) for their help with data collection and statistical analysis.

Participating institutions and principal investigators of the IDEC‐C2B8 Study Group include: Sapporo National Hospital (K. Aikawa, M. Nakata), Sapporo Hokuyu Hospital (M. Kasai, Y. Kiyama), Tochigi Cancer Center (Y. Kano, M. Akutsu), International Medical Center of Japan (A. Miwa, N. Takesako), National Cancer Center Hospital East (K. Itoh, T. Igarashi, K. Ishizawa), National Cancer Center Hospital (K. Tobinai, Y. Kobayashi, T. Watanabe), Tokyo Medical University (K. Ohyashiki, T. Tauchi), Tokai University School of Medicine (T. Hotta, K. Ando), Hamamatsu University School of Medicine (K. Ohnishi), Aichi Cancer Center Hospital (Y. Morishima, M. Ogura, Y. Kagami), Nagoya University School of Medicine (T. Kinoshita, T. Murate, H. Nagai), Nagoya National Hospital (K. Tsushita, H. Ohashi), Mie University School of Medicine (S. Kageyama, M. Yamaguchi), Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine (M. Taniwaki), Kyoto University School of Medicine (H. Ohno, T. Ishikawa), Shiga Medical Center for Adults (T. Suzuki), Center for Cardiovascular Diseases and Cancer, Osaka (A. Hiraoka, T. Karasuno), Hyogo Medical Center for Adults (T. Murayama, I. Mizuno), Hiroshima University School of Medicine (A. Sakai), National Kyushu Cancer Center (N. Uike), Nagasaki University School of Medicine (T. Maeda, K. Tsukasaki).

References

- 1. Reff ME, Carner K, Chambers KS et al. Depletion of B cells in vivo by a chimeric mouse human monoclonal antibody to CD20. Blood 1994; 83: 435–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maloney DG, Liles TM, Czerwinski DK et al. Phase I clinical trial using escalating single‐dose infusion of chimeric anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody (IDEC‐C2B8) in patients with recurrent B‐cell lymphoma. Blood 1994; 84: 2457–2466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tobinai K, Kobayashi Y, Narabayashi M et al. Feasibility and pharmacokinetic study of a chimeric anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody (IDEC‐C2B8, rituximab) in relapsed B‐cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol 1998; 9: 527–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McLaughlin P, Grillo‐López AJ, Link BK et al. Rituximab chimeric anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy for relapsed indolent lymphoma: half of patients respond to a four‐dose treatment program. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 2825–2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Igarashi T, Kobayashi Y, Ogura M et al. Factors affecting toxicity, response and progression‐free survival in relapsed patients with indolent B‐cell lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma treated with rituximab: a Japanese phase II study. Ann Oncol 2002; 13: 928–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fisher RI, LeBlanc M, Press OW et al. New treatment options have changed the survival of patients with follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 8447–8452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Horning JS. Follicular lymphoma, survival, and rituximab: is it time to declare victory? J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 4537–4538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheson BD, Leonard JP. Monoclonal antibody therapy for B‐cell non‐Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 613–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large‐B‐cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pfreundschuh M, Trümper L, Osterborg A et al. CHOP‐like chemotherapy plus rituximab versus CHOP‐like chemotherapy alone in young patients with good‐prognosis diffuse large‐B‐cell lymphoma: a randomised controlled trial by the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol 2006; 7: 379–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Habermann TM, Weller EA, Morrison VA et al. Rituximab‐CHOP versus CHOP alone or with maintenance rituximab in older patients with diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 3121–3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Armitage JO. How I treat patients with diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. Blood 2007; 110: 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Horning SJ, Rosenberg SA. The natural history of initially untreated low‐grade non‐Hodgkin’s lymphomas. N Engl J Med 1984; 311: 1471–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ardeshna KM, Smith P, Norton A et al. Long‐term effect of a watch and wait policy versus immediate systemic treatment for asymptomatic advanced‐stage non‐Hodgkin lymphoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2003; 362: 516–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brice P, Bastion Y, Lepage E et al. Comparison in low‐tumor‐burden follicular lymphomas between an initial no‐treatment policy, prednimustine, or interferon alfa: a randomized study from the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires‐Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15: 1110–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Solal‐Céligny P, Lepage E, Brousse N et al. Doxorubicin‐containing regimen with or without interferon alfa‐2b for advanced follicular lymphomas: final analysis of survival and toxicity in the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires 86 trial. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 2332–2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Colombat P, Salles G, Brousse N et al. Rituximab (anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody) as single first‐line therapy for patients with follicular lymphoma with a low tumor burden: clinical and molecular evaluation. Blood 2001; 97: 101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hainsworth JD, Litchy S, Barton JH et al. Single‐agent rituximab as first‐line and maintenance treatment for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma: a phase II trial of the Minnie Pearl Cancer Research Network. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 1746–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Witzig TE, Vukov AM, Habermann TM et al. Rituximab therapy for patients with newly diagnosed, advanced‐stage, follicular grade I non‐Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a phase II trial in the North Central Cancer Treatment Group. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 1103–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kaminski MS, Tuck M, Estes J et al. 131I‐tositumomab therapy as initial treatment for follicular lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 441–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Horning SJ, Negrin RS, Hoppe RT et al. High‐dose therapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation for follicular lymphoma in first complete or partial remission: results of a phase II clinical trial. Blood 2001; 97: 404–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Horning SJ. Natural history of and therapy for the indolent non‐Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Semin Oncol 1993; 5(Suppl 5): 75–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Czuczman MS, Grillo‐Lopez AJ, White CA et al. Treatment of patients with low‐grade B‐cell lymphoma with the combination of chimeric anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody and CHOP chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 268–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Friedberg JW, Taylor MD, Cerhan JR et al. Follicular lymphoma in the United States: first report of the national LymphoCare study. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 1202–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ogura M, Morishima Y, Kagami Y et al. Randomized phase II study of concurrent and sequential rituximab and CHOP chemotherapy in untreated indolent B‐cell lymphoma. Cancer Sci 2006; 97: 305–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hiddemann W, Kneba M, Dreyling M et al. Frontline therapy with rituximab added to the combination of cylophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) significantly improves the outcome for patients with advanced‐stage follicular lymphoma compared with therapy with CHOP alone: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low‐Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood 2005; 106: 3725–3732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Van Oers MH, Klasa R, Marcus RE et al. Rituximab maintenance improves clinical outcome of relapsed/resistant follicular non‐Hodgkin lymphoma in patients both with and without rituximab during induction: results of a prospective randomized phase 3 intergroup trial. Blood 2006; 108: 3295–3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maloney DG, Press OW, Braziel RM et al. A phase II trial of CHOP followed by rituximab chimeric monoclonal anti‐CD20 antibody for treatment of newly diagnosed follicular non‐Hodgkin’s lymphoma: SWOG 9800. Blood 2001; 98: 843a. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Czuczman MS, Weaver R, Alkuzweny B et al. Prolonged clinical and molecular remission in patients with low‐grade or follicular non‐Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated with rituximab plus CHOP chemotherapy: 9‐year follow‐up. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 4711–4716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marcus R, Imrie K, Solal‐Celigny P et al. Phase III study of R‐CVP compared with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone alone in patients with previously untreated advanced follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 4579–4586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non‐Hodgkin’s lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 1244–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tobinai K, Kohno A, Shimada Y et al. Toxicity grading criteria of the Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG). Jpn J Clin Oncol 1993; 23: 250–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Solal‐Céligny P, Roy P, Colombat P et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index. Blood 2004; 104: 1258–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Buske C, Hoster E, Dreyling M et al. Rituximab in combination with CHOP in patients with follicular lymphoma: analysis of treatment outcome of 552 patients treated in a randomized trial of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG) after a follow‐up of 58 months. Blood 2008; 112: 901a (Abstract 2599). Available from URL: http://abstracts.hematologylibrary.org/cgi/content/abstract/112/11/2599?maxtoshow=&hits=10&RESULTFORMAT=&fulltext=Buske+C&searchid=1&FIRSTINDEX=0&volume=112&issue=11&resourcetype=HWCIT. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Forstpointner R, Unterhalt M, Dreyling M et al. Maintenance therapy with rituximab leads to a significant prolongation of response duration after salvage therapy with a combination of rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone (R‐FCM) in patients with recurring and refractory follicular and mantle cell lymphomas: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG). Blood 2006; 108: 4003–4008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hainsworth JD, Litchy S, Shaffer DW et al. Maximizing therapeutic benefit of rituximab: maintenance therapy versus re‐treatment at progression in patients with indolent non‐Hodgkin’s lymphoma – a randomized phase II trial of the Minnie Pearl Cancer Res Network. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 1088–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hochster H, Weller E, Gascoyne RD et al. Maintenance rituximab after cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone prolongs progression‐free survival in advanced indolent lymphoma: results of the randomized phase III ECOG1496 study. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 1607–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ghielmini M, Schmitz SF, Cogliatti SB et al. Prolonged treatment with rituximab in patients with follicular lymphoma significantly increases event free survival and response duration compared with the standard weekly 4 schedule. Blood 2004; 103: 4416–4423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Press OW, Unger JM, Braziel RM et al. Phase II trial of CHOP chemotherapy followed by tositumomab/iodine I‐131 tositumomab for previously untreated follicular non‐Hodgkin’s lymphoma: five‐year follow‐up of Southwest Oncology Group Protocol S9911. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 4143–4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Morschhauser F, Radford J, Van Hoof A et al. Phase III trial of consolidation therapy with yttrium‐90‐ibritumomab tiuxetan compared with no additional therapy after first remission in advanced follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 5156–5164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Federico M, Bellei M, Marcheselli L et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index 2: a new prognostic index for follicular lymphoma developed by the international follicular lymphoma prognostic factor project. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 4555–4562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]