Abstract

Cell permeabilization using microbubbles (MB) and low‐intensity ultrasound (US) have the potential for delivering molecules into the cytoplasm. The collapsing MB and cavitation bubbles created by this collapse generate impulsive pressures that cause transient membrane permeability, allowing exogenous molecules to enter the cells. To evaluate this methodology in vitro and in vivo, we investigated the effects of low‐intensity 1‐MHz pulsed US and MB combined with cis‐diamminedichloroplatinum (II) (CDDP) on two cell lines (Colon 26 murine colon carcinoma and EMT6 murine mammary carcinoma) in vitro and in vivo on severe combined immunodeficient mice inoculated with HT29‐luc human colon carcinoma. To investigate in vitro the efficiency of molecular delivery by the US and MB method, calcein molecules with a molecular weight in the same range as that of CDDP were used as fluorescent markers. Fluorescence measurement revealed that approximately 106–107 calcein molecules per cell were internalized. US–MB‐mediated delivery of CDDP in Colon 26 and EMT6 cells increased cytotoxicity in a dose‐dependent manner and induced apoptosis (nuclear condensation and fragmentation, and increase in caspase‐3 activity). In vivo experiments with xenografts (HT29‐luc) revealed a very significant reduction in tumor volume in mice treated with CDDP + US + MB compared with those in the US + CDDP groups for two different concentrations of CDDP. This finding suggests that the US–MB method combined with chemotherapy has clinical potential in cancer therapy. (Cancer Sci 2008; 99: 2525–2531)

Microbubbles (MB) have been developed as ultrasound (US) contrast agents with a diameter of less than 10 µm. The components of their shell membrane vary (albumin, lipid, or polymer), and gases such as air or perfluorocarbons are internalized in them.( 1 , 2 , 3 ) These bubbles oscillate non‐linearly in an US field and emit harmonic and subharmonic acoustic signals, thereby enabling differentiation between acoustic scattering and vascular signatures. In addition, because these bubbles behave similar to red blood cells, they have been used to evaluate the blood pool and blood flow at the microvascular level.( 4 )

Microbubbles collapse in the presence of low‐intensity US. There is evidence that impulsive pressures generated by either collapsing MB( 5 , 6 ) or the cavitation bubbles created by this collapse may permeabilize the plasma membrane of neighboring cells.( 7 , 8 ) This process results in the diffusion of nearby exogenous molecules into the cytoplasm and a subsequent biological response.( 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ) Because these impulsive pressures can be induced by high‐intensity US,( 12 , 13 ) substantial thermal and mechanical side effects can be reduced using the US–MB method.

The US–MB method is non‐toxic and non‐immunogenic, and allows local or systemic administration. This method can be used to deliver exogenous molecules into dividing and non‐dividing cells and has been investigated as an approach for in vivo gene transfer and molecular delivery.( 14 , 15 , 16 ) In any case, the efficiency of molecular delivery depends on the size of the molecules to be delivered.( 17 , 18 ) The amount of molecules increases with decreasing molecular weight. Thus, it is expected that this methodology will be useful for therapeutic strategies involving drugs with small molecular sizes. Cis‐diamminedichloroplatinum (II) (cisplatin; CDDP) is one of the most effective and commonly used chemotherapeutics, possessing a molecular weight of 300. CDDP has been used for the treatment of many solid tumors, including those of the ovaries, testicles, bladder, lung, and head and neck.( 19 ) Increasing CDDP penetration into the tumor cells could further improve its therapeutic efficacy. In the present study, we estimated the number of CDDP molecules internalized by the US–MB method using calcein molecules with molecular weights in the same range as that of CDDP as fluorescent markers. Subsequently, we assessed the therapeutic potential of the combination of CDDP and US with MB in vitro and in vivo and demonstrated that this combination induces apoptotic effects, and increases the therapeutic efficacy.

Materials and Methods

In vitro and in vivo studies were carried out in accordance with the ethical guidelines approved by Tohoku University.

Cell preparation. Human embryonic kidney (293T) cells were a generous gift from Dr Ono of Tohoku University. Murine mammary carcinoma (EMT6) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). Murine colon carcinoma (Colon 26) cells were obtained from the Cell Resource Center for Biomedical Research of the Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer, Tohoku University (Sendai, Japan). Human colon carcinoma (HT‐29‐luc) cells stably transfected with a plasmid carrying the firefly luciferase gene driven by a cytomegalovirus promoter were obtained from Xenogen (Alameda, CA, USA). Colon 26 and HT‐29‐luc cells were cultured under standard conditions in RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat‐inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 1%l‐glutamine–penicillin–streptomycin (Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), whereas 293T and EMT6 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Sigma‐Aldrich) containing the same supplements as those added to the RPMI‐1640 medium. HT29‐luc cells were selected in 1 mg/mL geneticin (G418) (Sigma‐Aldrich). Cells cultured in a 10‐cm culture dish were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C under an atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and 95% air. The total cell counts and viability were counted in a hemocytometer by the trypan blue dye exclusion method( 20 ) prior to US exposure. Only cells in their exponential growth phase with a viability ≥99% were used for the study.

Microbubbles. MB were created in an aqueous dispersion of 2 mg/mL 1,2‐distearoyl‐sn‐glycero‐3‐phosphocholine (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL, USA) and 1 mg/mL polyethylene glycol 40 stearate (Sigma‐Aldrich) using a 20‐kHz sonicator (Vibra Cell; Sonics and Materials, Danbury, CT, USA) in the presence of C3F8 gas.( 21 ) The lipid molecules that formed components of the MB surface were confirmed by staining the molecules with 3 µmol/L FM1‐43 (excitation 479 nm, emission 598 nm; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) and observing them under an inverted microscope (IX81; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The peak diameter and the zeta potential of the MB were determined to be 1272 ± 163 nm (n = 7) and –4.1 ± 0.85 mV (n = 3), respectively, by using a laser diffraction particle size analyzer (particle range 0.6 nm–7 µm; ELSZ‐2; Otsuka Electronics, Osaka, Japan).

Ultrasound exposure. Three 1‐MHz submersible US probes were used. A 12‐mm (Fuji Ceramics, Fujinomiya, Japan) and a 30‐mm diameter probe (BFC Applications, Fujisawa, Japan) were used for the in vitro experiments, whereas 38‐mm diameter probes (Fuji Ceramics) were used for the in vivo experiments. Each probe was placed in the test chamber (380 mm × 250 mm × 130 mm) that was previously filled with tap water. Signals of 1 MHz were generated by a multifunction synthesizer (WF1946A; NF Co., Yokohama, Japan) and amplified with a high‐speed bipolar amplifier (HSA4101; NF Co.). The pressure values were measured using a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) needle hydrophone (PVDF‐Z44‐1000; Specialty Engineering Associates, Soquel, CA, USA) at a stand‐off distance of 1 mm from the transducer surface by using a stage control system (Mark‐204‐MS; Sigma Koki, Tokyo, Japan). The signals from both the amplifier and the hydrophone were recorded onto a digital phosphor oscilloscope (Wave Surfer 454, 500 MHz, 1 MΩ[16 pF]; LeCroy Co., Chestnut, NY, USA) in top water degassed with transducer (SPN‐620) generated by ultrasonic generator α2 (GP‐622D) (Tiyoda Electric Co., Chikuma, Japan). The positive and negative peak values of the pressures were the same. Two intensities, 0.5 and 1.0 W/cm2, were used in the in vitro experiments. The duty cycle was 50%, the number of pulses was 2000, the pulse repletion frequency was 250 Hz, and the exposure time was 10 s. For the in vivo experiments, the intensity was 3.0 W/cm2, the duty cycle was 20%, the number of pulses was 200; the pulse repletion frequency was 1000 Hz, and the exposure time was 60 s. The intensity was defined as the average rate of flow of energy through a unit area placed normal to the direction of propagation.

In vitro quantization of calcein uptake. The 293T cells (5 × 104 cells/well) were seeded in complete medium onto 48‐well plates and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. On the next day, the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing 200 µmol/L calcein (molecular weight 622) (excitation 494 nm, emission 517 nm; Sigma‐Aldrich) with and without MB (10% v/v). After US exposure for 10 s, the cells were washed with phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS), trypsinized, and collected in a 15‐mL conical tube. Thereafter, the cells were washed three times and transferred to a 1.5‐mL conical tube in which they were pelleted. The pellets were lysed in 200 µL reporter lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and subsequently frozen at –80°C for 15 min. The cells were thawed on ice. Each cell lysate was centrifuged at 12 000g for 2 min to pellet the cell debris. Twenty microliters of the supernatant was examined for the uptake of fluorescent molecules using Mx3000P software (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). The fluorescence of these molecules was excited using a quartz tungsten halogen lamp (350–750 nm), and the emission was collected with a 492–516‐nm bandpass filter. The fluorescence data were analyzed with MxPro QPCR Software (Stratagene). The total protein content from an aliquot of each sample of supernatant was calculated by establishing albumin standard curves (BCA protein assay kit; Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). In addition, two other standard curves were utilized: one to determine the total protein content of the cells, and the other to determine the concentration and intensity of the fluorescence. The experiment was carried out with samples and standards in duplicate, and the absorption of the protein was measured at 562 nm using a plate reader (Sunrise; Tecan Austria, Salzburg, Austria) with the data analysis software LS‐Plate manager RD 2001 (Win) (Sunrise). The number of equivalent fluorescent molecules per cell was determined from the calibration curves.

Imaging of confocal fluorescence microscopy. The 293T cells (5 × 104 cells/well) were seeded in complete medium onto alternate 48‐well plates to prevent US exposure of neighboring cells.( 8 ) On the next day, the medium was replaced with fresh medium (110 µL) containing calcein (200 µmol/L) with and without MB (10% v/v). After US exposure of 10 s, the plates were incubated for 24 h. Thereafter, the cells were washed three times with PBS and trypsinized. Finally, the cell pellet was resuspended in 60 µL propidium iodide (PI) (excitation 536 nm, emission 617 nm; Molecular Probes) (0.7 µg/mL) and incubated at room temperature for 10–15 min. The calcein and PI fluorescence intensities were determined with a confocal microscope (FV1000; Olympus). A ×60 oil‐immersion objective lens with a numerical aperture of 1.25 was used. Calcein and PI fluorescence were excited with the 488‐nm line of an argon laser. The laser excitation beam was directed to the specimen through a 488‐nm dichroic beam splitter. The emitted fluorescence was collected through a 510–550‐nm bandpass emission filter in the green channel and a 580‐nm longpass filter in the red channel. Computer‐generated images of 1‐µm optical sections were obtained at the approximate geometric center of the cell as determined by repeated optical sectioning.

In vitro delivery of CDDP. CDDP (molecular weight 300) was donated by Nihon Kayaku (Tokyo, Japan). Colon 26 and EMT6 cells were seeded in complete medium onto 10‐cm culture dishes. Both cells were trypsinized, counted, and transferred into 15‐mL round tubes at concentrations of 5 × 105 and 3 × 105 cells/mL, respectively. For control samples, 1 mL complete medium was used as the sample solution; for treated samples, the sample solution was mixed with 800 µL complete medium, 100 µL CDDP solution (0.5–1.0 mmol/L), and 100 µL MB solution (7% v/v). Each tube was positioned above a 30‐mm diameter US probe that was immersed in tap water and exposed to US (10 s; 0.5 W/cm2). After exposure, 4 mL PBS was added to each tube and centrifuged for 5 min at 4°C (350g). The cells were washed twice with PBS and subsequently seeded in 1 mL complete medium onto 24‐well plates. The plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The cell viability was determined by a 3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2, 5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay as described previously.( 22 ) Each experiment was carried out with five samples. For each experiment, the mean percentage of treated samples was divided by the mean percentage of control samples to obtain the survival fraction. The mean of five survival fractions was calculated for each condition. The survival fraction of each cell line was measured at the CDDP concentration at which the highest statistical significance was obtained.

In vitro analysis of apoptosis. Colon 26 (5 × 104 cells/well) cells were seeded onto alternate 48 wells to prevent the US exposure of neighboring cells.( 8 ) The medium was replaced with fresh medium (110 µL) containing CDDP (1.5 mg) with and without MB (7% v/v). After US exposure, the plates were incubated for 1 h in a 5% CO2 incubator, supplemented with 390 µL complete medium; subsequently, the plates were incubated for an additional 24 h at 37°C in the same incubator. The final concentration of CDDP was 10 µmol/L. The cell viability was determined by an MTT assay as described previously.( 22 ) Staining with 4′,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma‐Aldrich) was carried out for observing nuclear condensation and fragmentation. Twenty‐four hours after the addition of CDDP, the cells were washed with PBS, stained with 100 µL DAPI (100 ng/mL) solution, and observed under an inverted microscope (IX 81). DAPI fluorescence of the cell nuclei was visualized by excitation at 330–385 nm with a 420‐nm barrier filter. For determining the induction of apoptotic mediator proteins, caspase‐3 activity was measured using a colorimetric assay kit (Medical and Biological Laboratories, Woburn, MA, USA) 24 h after the treatment. In brief, the treated cells were collected from 12 wells of the 48‐well plates and suspended in cell lysis buffer. Aliquots of protein were incubated in a reaction buffer containing 10 mmol/L dithiothreitol (DTT) at 37°C for 1 h. A p‐nitroaniline‐conjugated synthetic peptide was used as the substrate. The caspase activity was calculated by measuring the optic absorbance at 400 nm using a plate reader with the data analysis software LS‐Plate manager RD 2001 (Win).

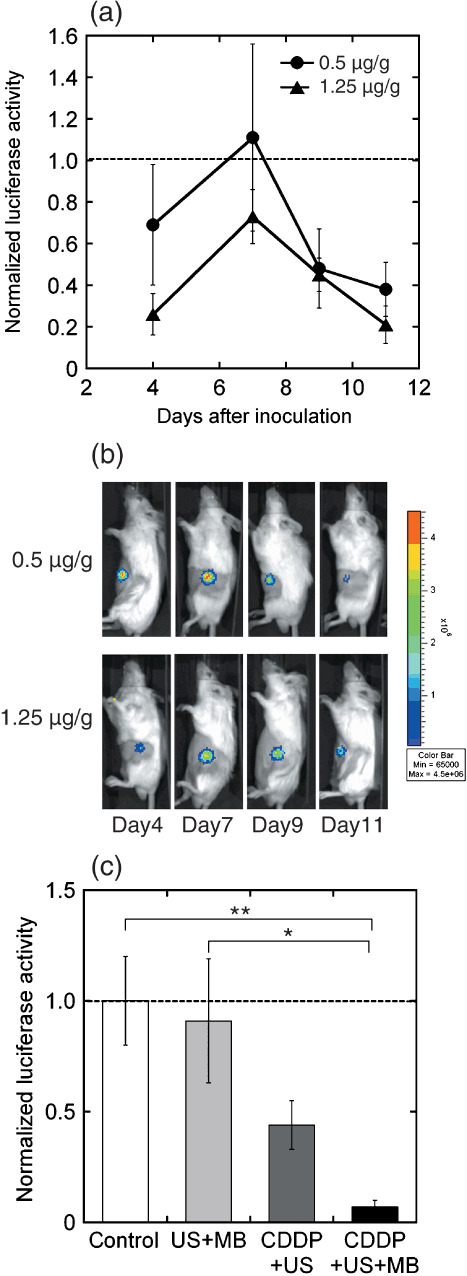

In vivo therapeutic effects. To evaluate the antitumor effects of MB, the antitumor effects of CDDP + US and CDDP + US + MB were compared using xenografts of HT29‐luc cells. Two CDDP concentrations (0.5 and 1.25 µg/g bodyweight) were used. HT29‐luc cells (1 × 106 cells) in 100 µL saline were injected subcutaneously into the right and left flanks of 16 male severe combined immunodeficient mice aged 6–9 weeks (mouse bodyweight was set to 20 g). The mice were assigned randomly into two groups. On days 3, 7, and 10, all mice were injected intratumorally with the following assigned treatments. (i) Four mice received 20 µL CDDP (0.5 µg/µL bodyweight) with 80 µL saline per site following US exposure (CDDP + US), and four others received 20 µL CDDP (0.5 µg/µL bodyweight) with 30 µL saline and 50 µL MB per site following US exposure (CDDP + US + MB). (ii) Four mice received 50 µL CDDP (1.25 µg/µL bodyweight) with 50 µL saline per site following US exposure (CDDP + US), and four others received 50 µL CDDP (1.25 µg/µL bodyweight) with 50 µL MB per site following US exposure (CDDP + US + MB). The tumors were immersed in tap water with a temperature of 37°C, positioned just above the 38‐mm diameter US probe, and exposed to US (3.0 W/cm2, 60 s). Bioluminescence induced by CDDP + US + MB was normalized with that of CDDP + US at each concentration (0.5 and 1.25 µg/g bodyweight) on days 4, 7, 9, and 11 to provide the antitumor effects of MB.

Bioluminescence imaging. On days 4, 7, 9, and 11, the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane. Subsequently, they were injected intraperitoneally with luciferin (150 µg/g bodyweight) and placed on the in vivo imaging system (IVIS100; Xenogen). The bioluminescence signals were monitored at 10‐s time intervals after 10 min luciferin administration. The signal intensity was quantified as the sum of all detected photon counts within the region of interest after subtraction of the measured background luminescence. The light intensity closely correlated with the tumor volume (EMT6‐luc) up to 100 mm3, at which point the tumor volume was calculated according to the formula (π/6) × (width)2 × (length).( 21 ) In the present experiment, all tumors (HT29‐luc) with a volume less than 100 mm3 were subjected to treatment.

Statistical analysis. All measurements are expressed as mean ± SEM. An overall difference between the groups was determined by one‐way analysis of variance (one‐way ANOVA). When the one‐way ANOVA results were significant for three samples, the differences between each group were estimated using the Tukey–Kramer test. Simple comparisons of the mean and SEM of the data were carried out using Student's t‐test. The differences were considered to be significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Uptake of fluorescent molecules. Calcein, which has a molecular weight of 622 (calculated stokes radius of 0.68),( 23 ) was used as a fluorescent marker to evaluate small‐molecule entry in cancer cells upon US–MB stimulation. As the molecular weight of CDDP is 300 (calculated stokes radius is 0.48 nm), calcein can be considered to represent a realistic marker of CDDP entry into tumor cells.

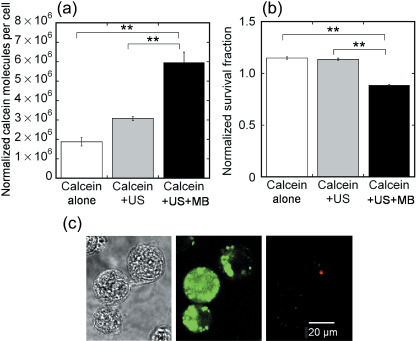

The exposure of cells to US in the presence of MB resulted in the delivery of 106–107 calcein molecules per cell (Fig. 1a). This represents a significant increase in the uptake of fluorescent molecules compared to calcein alone and calcein + US. Figure 1b shows that this effect was achieved with a very limited loss of cell viability that was measured by MTT assay, where the survival fraction rate due to MB alone was not investigated as it was found that MB alone did not contribute to cell viability.( 24 ) To confirm that the calcein molecules actually entered the cytoplasm, confocal fluorescence microscopic analysis was carried out. Figure 1c shows the differential interference contrast and fluorescence images or the representative viable 293T cells exposed to US in the presence of MB. PI staining was also carried out with some instances of fluorescence staining to confirm that the cells that acquired calcein were viable and excluded PI. Some cells treated with US in the presence of MB demonstrated intense fluorescence distributed uniformly throughout the entire cell, whereas other cells demonstrated localized intense fluorescence (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

Uptake of fluorescent molecules by 293T cells. (a) Mean fluorescence uptake under various conditions (calcein alone, calcein + ultrasound [US], and calcein + US + microbubbles [MB]). The calcein + US + MB condition results in a significant increase in the uptake of fluorescent molecules (6.0 ± 0.5 ¥ 106 molecules per cell) compared to calcein alone and calcein + US. Calcein alone (n = 4), calcein + US (n = 4), calcein + US + MB (n = 4). (b) Cell viability measured by the a 3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2, 5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. The survival fraction is decreased slightly by the effect of US + MB. Calcein alone (n = 4), calcein + US (n = 4), calcein + US + MB (n = 4). (c) Confocal microscopy showing differential interference contrast (left) and fluorescence images (middle) or representative viable 293T cells (right) exposed to US in the presence of MB. Propidium iodide (PI) staining was carried out with fluorescence staining in some cases to confirm that the cells that acquired calcein were viable and excluded PI. Scale bars = 20 mm. Ultrasound intensity 1.0 W/cm2; duty cycle 50%; number of pulses 2000; pulse repletion frequency 250 Hz; and exposure time 10 s. **P < 0.01.

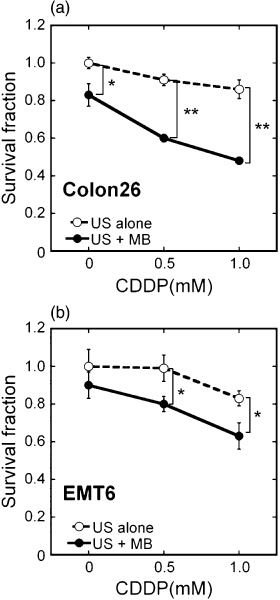

Cytotoxicity in vitro. The cytotoxicity of various doses of CDDP in the presence of US with and without MB was tested on Colon 26 and EMT6 cells (Fig. 2). A marked increase in CDDP toxicity was observed under the US–MB conditions, whereas US alone did not significantly affect cell survival with various CDDP concentrations. The CDDP toxicity depended slightly on the cell type.

Figure 2.

Potentiation of in vitro cis‐diamminedichloroplatinum (II) (CDDP) cytotoxicity in Colon 26 and EMT6 cells. (a) Colon 26: (s) ultrasound (US) alone (n = 5) and (d) US + microbubbles (MB) (n = 5). (b) EMT6: (s) US alone (n = 5) and (d) US + MB (n = 5). Cell survival was measured by a 3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2, 5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay 24 h after US exposure. US intensity 0.5 W/cm2; duty cycle 50%; number of pulses 2000; pulse repletion frequency 250 Hz; and exposure time 10 s. The bars represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

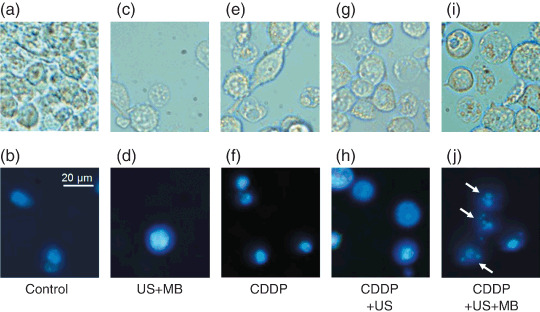

Apoptosis assay. CDDP is known to induce apoptosis.( 25 ) We confirmed the involvement of apoptosis in mediating cytotoxicity in response to CDDP. Cells undergoing apoptosis demonstrate characteristic nuclear morphological changes with DAPI staining. Figure 3 shows phase contrast and DAPI images of Colon 26 cells. Untreated control cells (Fig. 3a,b) and cells treated with US + MB (Fig. 3c,d), CDDP alone (Fig. 3e,f), and CDDP + US (Fig. 3g,h) showed extremely little condensed or fragmented chromatin. The majority of cells treated with CDDP + US + MB (Fig. 3i,j) displayed apoptotic features, including condensed nuclei and nuclear fragmentation.

Figure 3.

Nuclear condensation and fragmentation. (a,c,e,g,i) Differential interference contrast and (b,d,f,h,j) 4′,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI) fluorescence images of representative viable Colon 26 cells 24 h after treatment. 10 µmol/L cis‐diamminedichloroplatinum (II) (CDDP): (a,b) control, (c,d) ultrasound (US) + microbubbles (MB), (e,f) CDDP, (g,h) CDDP + US, and (i,j) CDDP + US + MB. Round or shrunken nuclei of DAPI‐stained cells (white arrows) are hallmarks of apoptosis in (j). Experiments were repeated three times with similar results. Scale bar = 20 µm. Ultrasound intensity 1.0 W/cm2; duty cycle 50%; number of pulses 2000; pulse repletion frequency 250 Hz; and exposure time 10 s.

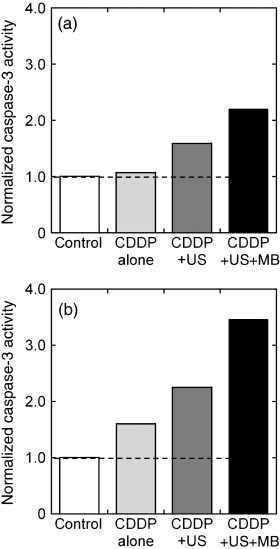

Induction of caspase‐3 has been suggested as a marker of apoptosis.( 26 ) Figure 4 shows that treatment with US + MB activates caspase‐3 as compared to treatment with CDDP alone or with CDDP + US. The caspase activity increases with time. Taken together, the data presented in 3, 4 demonstrate that the CDDP + US + MB combination decreases cell viability and that this reduction in cell survival is associated with increased induction of apoptosis. In the present study, we did not consider the activation of caspase‐3 by US because US alone did not contribute to the survival fraction (Fig. 2) and subsequent apoptosis induction (Fig. 3).

Figure 4.

Upregulation of the proapoptotic gene caspase‐3. Colon 26 cells were treated with cis‐diamminedichloroplatinum (II) (CDDP) (10 µmol/L) in the presence of ultrasound (US) with and without microbubbles (MB). Caspase‐3 activity was measured at 24 h after treatment. Twelve wells from 48‐well plates were analyzed for each condition. Results are expressed as the number of molecules of p‐nitroaniline (pNA) (nmol) released by 1 mg of protein in (a) 1 and (b) 2 h. Ultrasound intensity 1.0 W/cm2; duty cycle 50%; number of pulses 2000; pulse repletion frequency 250 Hz; and exposure time 10 s.

In vivo therapeutic effects of MB. From the above in vitro experiments, we found that MB associated with US are able to trigger the uptake of small molecules (Fig. 1), thereby inducing antitumor effects (Fig. 2) and apoptosis (3, 4) in conjunction with CDDP. Thereafter, we investigated the in vivo antitumor effects of using MB, in cases in which the xenografts of HT29‐luc cells were used. We investigated the antitumor effects of CDDP + US + MB on the xenografts with two different CDDP concentrations (0.5 and 1.25 µg/g bodyweight) on days 4, 7, 9, and 11. The luciferase activity for each concentration of CDDP + US + MB was normalized with each concentration of CDDP + US that was administered previously (Fig. 5a) in order to determine the antitumor effects of MB alone. The activities of the MB were recognized after day 7 (second treatment) in both groups. On day 11, a significant reduction was observed in the CDDP + US + MB group compared to the control and US + MB groups. These effects were recognized by bioluminescence images (Fig. 5b). Figure 5c shows antitumor effects for different conditions (US + MB, CDDP + US, CDDP + US + MB) at day 11, where the CDDP concentration was 1.25 µg/g bodyweight, and the bioluminescence of each condition was normalized with that of the control at day 11. There was no significant difference between control and US + MB. CDDP alone was recognized as the difference between US + MB and CDDP + US, where CDDP alone decreased US + MB by 48.4%. MB further reduced CDDP + US by 84.1%.

Figure 5.

Antitumor effects of cis‐diamminedichloroplatinum (II) (CDDP) + ultrasound (US) + microbubbles (MB) on HT29‐luc xenografts with two different CDDP concentrations (0.5 and 1.25 µg/g bodyweight) on days 4, 7, 9, and 11. Ultrasound intensity 3.0 W/cm2; duty cycle 20%; number of pulses 200; pulse repletion frequency 1000 Hz; and exposure time 60 s. Luciferase activity after (a) treatment and (b) bioluminescence imaging. The luciferase activity under each concentration of CDDP + US + MB was normalized with each concentration of CDDP + US. CDDP (0.5 µg/g bodyweight) + US (n = 4), CDDP (0.5 µg/g bodyweight) + US + MB (n = 4), CDDP (1.25 µg/g bodyweight) + US (n = 4), CDDP (1.25 µg/g bodyweight) + US + MB (n = 4). (c) The luciferase activity normalized with that of control at day 11, where the concentration of CDDP was 1.25 µg/g bodyweight. Control (n = 5), US + MB (n = 4). The bars represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Discussion

The US–MB method permeabilizes the cell membrane directly, thereby allowing the delivery of exogenous molecules into the cells. Electroporation is also a method that is used to permeabilize the cell membrane by direct application of an external electric field. Cemazar et al. delivered CDDP into both murine sarcoma cisplatin‐sensitive TBL.C12 cells and their resistant subclones, namely, TBL.C12.Pt cells.( 27 ) These cells were treated in vivo by electroporation, and their platinum content was measured by atomic absorption. Based on their findings, the authors suggested that 106 platinum molecules were delivered into TBL.C12 and TBL.C12.Pt cells at 0.05 and 0.46 µg/mL, respectively, where these concentrations correspond to the 50% inhibitory concentration values of platinum for these cells. Our finding that 106–107 calcein molecules were internalized per cell at 200 µmol/L, as shown in Figure 1a, is in agreement with the finding of Cemazar et al. and demonstrates that US–MB permeabilization is as efficient as electroporation in the permeabilization of cell membranes.

There are several anticancer drugs with a similar molecular weight to CDDP. For example, the molecular weight of vincristine is 923, and that of taxol is 854. There is not even one order difference between these molecules and cisplatin, which has a molecular weight of 300. Therefore, we think that the same number of molecules will be delivered into cells by this method. However, it is noted that the number of molecules internalized is not directly correlated with subsequent antitumor effects.

Following the application of MB and US, the cell membrane surface becomes rough and is characterized by depressions that are reversible within 24 h after US exposure.( 28 , 29 ) Collapsed MB or cavitation bubbles generated by collapsed MB induce impulsive pressures such as liquid jets and shock waves; these pressures affect the neighboring cells. The shock wave propagation distance from the center of a cavitation bubble that has the potential to damage the cell membrane is considerably larger than the maximum radius of the cavitation bubble.( 8 ) Molecular dynamic simulation has revealed that the cell membrane affected by the shock wave is deformed, thereby allowing the entry of exogenous molecules into the cells.( 30 ) Although the membrane permeabilization time has not been measured accurately, it has been reported that the membrane reseals within 80 s when it is permeabilized by shock waves.( 31 ) When 1176 water molecules are delivered into a lipid bilayer comprising 128 dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine molecules, a water pore of 1.9‐nm diameter is formed in the lipid bilayer;( 30 ) this water pore is larger than the CDDP with a diameter of 0.48 nm.

As shown in Figure 1, the US–MB method enhances cell permeability, thereby allowing the delivery of a large number of CDDP molecules into the cells. The combination of high‐intensity ultrasound (shock waves) and generated cavitation bubbles – the same concept as that used in the US–MB method – can deliver CDDP molecules into the cells.( 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ) However, the cytotoxicity of CDDP depends on the cell type (Fig. 2); therefore, resistance to CDDP is not completely overcome simply by the application of US and MB (or cavitation bubbles).

The delivery of CDDP into cells induces apoptosis.( 36 ) Apoptotic pathways involved in mediating CDDP‐induced cellular effects have been investigated thoroughly.( 37 ) The apoptotic induction resulting from CDDP delivery was confirmed by DAPI staining (Fig. 3) and measurement of caspase‐3 activity (Fig. 4). The upregulation of caspase‐3 coincides with the observations of previous reports.( 10 , 11 , 38 , 39 ) Caspase‐3 is a key effector of apoptosis that is responsible for the proteolytic cleavage of cytoskeletal proteins, kinase, and DNA repair enzymes.( 40 ) The signaling pathway that mediates US‐induced apoptosis has been investigated previously.( 11 , 41 )

In the in vivo experiments, CDDP and MB were injected intratumorally on days 3, 7, and 10 after the injection with tumor cells (HT29‐luc), and the tumor was exposed to US. The normalized luciferase activity increased by day 7 and decreased afterwards. This indicates that the antitumor effects resulted from the activity of MB becoming dominant against the tumorigenesity. Tumor growth was suppressed effectively, indicating that the US–MB method provides a synergistic effect with antitumor drugs.( 42 , 43 )

We used a local administration system in the in vivo experiments (direct injection of CDDP + MB and local US exposure). This local exposure to US has more advantages than the currently available local therapies such as surgery and radiotherapy. However, the usefulness of local therapy is expected to be limited to a particular tumor or a particular tumor stage. For example, hepatocellular carcinomas and brain gliomas seldom metastasize to other organs. Instead, hepatocellular carcinomas and gliomas grow within the liver and brain, respectively, and eventually cause death without metastasizing to other organs. Because these tumors are fed by a tumor‐feeding artery, the arterial injection of any anticancer agent (ACA) into the tumor‐feeding artery is the most direct way of delivering it into the tumors, mainly because of the first‐path effect. With regard to superficial bladder cancer recurrences, half of all such cases recur, and 10–30% progress to a higher grade or stage and form local invasive cancer. Intravesical administration of ACA is known to prolong the duration of progression‐free survival. For a clinically randomized phase III trial conducted in patients with stage III ovarian cancer, local intraperitoneal injection of ACA can prolong the duration of overall survival, compared to systemic intravenous injection.( 44 )

According to the above mentioned evidence, we believe that it is possible to establish a local ACA delivery system in experimental animal models in anticipation of future clinical trials. The US–MB method has the advantages of tissue specificity and non‐invasiveness. In addition, this method can be applied repeatedly to patients without immunogenicity.( 21 ) However, the efficiency of molecular delivery into cells is low, and the subsequent bioeffects are not adequate to be investigated by clinical trials. Recently, many types of MB with characteristics of tissue specificity and drug incorporation have been developed( 45 ) and the US exposure conditions have been investigated.( 46 , 47 ) Combination of the US–MB method with other physical methods such as hyperthermia has also been investigated.( 48 ) In our laboratory, we have investigated the relationship between the physicochemical properties (zeta potential, size, and lipid components) of MB and the transfection efficiency (data not shown).

In conclusion, in the present study we have demonstrated that the US–MB method combined with the well‐known chemotherapeutic agent CDDP has great therapeutic potential in cancer therapy. By reducing the dose of CDDP required to induce cell death through the abovementioned method it may be possible to increase the therapeutic action of the drug and to limit the toxicity of the treatment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fuki Oosawa for her technical assistance. S.M. acknowledges Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research (B) (19390507) and H.M. acknowledges Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research (B) (19592334). G.V. acknowledges the program and projects grants from Cancer Research, UK, Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale (INSERM), Ligue Contre le Cancer and support through grant 0607‐3D1615–66/AO INSERM from the French National Cancer Institute. T.K. acknowledges Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research (B) (20300173), and Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Area MEXT (20015005). Y.M. and T.K. acknowledge Grant for Research on Nanotechnical Medical, the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan (H19‐nano‐010). G.V. and T.K. acknowledge the Japan–France Integrated Action Program Joint Project. CDDP was donated by Nihon Kayaku (Tokyo, Japan).

References

- 1. Klibanov AL. Ligand‐carrying gas‐filled microbubbles: ultrasound contrast agents for targeted molecular imaging. Bioconjug Chem 2005; 16: 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Harvey CJ, Blomley MJ, Eckersley RJ, Cosgrove DO. Developments in ultrasound contrast media. Eur Radiol 2001; 11: 675–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barak M, Katz Y. Mcirobubbles: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Chest 2005; 128: 2918–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lindner JR. Molecular imaging with contrast ultrasound and targeted microbubbles. J Nucl Cardiol 2004; 11: 215–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen WS, Matula TJ, Crum LA. The disappearance of ultrasound contrast bubbles: observations of bubble dissolution and cavitation nucleation. Ultrasound Med Biol 2002; 28: 793–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Miller DL, Dou C. Membrane damage thresholds for 1‐ to 10‐MHz pulsed ultrasound exposure of phagocytic cells loaded with contrast agent gas bodies in vitro . Ultrasound Med Biol 2004; 30: 973–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hallow DM, Mahajan AD, McCutchen TE, Prausnitz MR. Measurement and correlation of acoustic cavitation with cellular bioeffects. Ultrasound Med Biol 2006; 32: 1111–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kodama T, Tomita Y, Koshiyama K, Blomley MJ. Transfection effect of microbubbles on cells in superposed ultrasound waves and behavior of cavitation bubble. Ultrasound Med Biol 2006; 32: 905–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feril LB Jr, Tsuda Y, Kondo T et al . Ultrasound‐induced killing of monocytic U937 cells enhanced by 2,2′‐azobis (2‐amidinopropane) dihydrochloride. Cancer Sci 2004; 95: 181–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Firestein F, Rozenszajn LA, Shemesh‐Darvish L, Elimelech R, Radnay J, Rosenschein U. Induction of apoptosis by ultrasound application in human malignant lymphoid cells: role of mitochondria–caspase pathway activation. Ann NY Acad Sci 2003; 1010: 163–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Honda H, Kondo T, Zhao QL, Feril LB Jr, Kitagawa H. Role of intracellular calcium ions and reactive oxygen species in apoptosis induced by ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol 2004; 30: 683–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chaussy C, Thuroff S, Rebillard X, Gelet A. Technology insight: high‐intensity focused ultrasound for urologic cancers. Nat Clin Pract Urol 2005; 2: 191–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Colombel M, Gelet A. Principles and results of high‐intensity focused ultrasound for localized prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2004; 7: 289–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hou CC, Wang W, Huang XR et al . Ultrasound–microbubble‐mediated gene transfer of inducible Smad7 blocks transforming growth factor‐β signaling and fibrosis in rat remnant kidney. Am J Pathol 2005; 166: 761–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shimamura M, Sato N, Taniyama Y et al . Gene transfer into adult rat spinal cord using naked plasmid DNA and ultrasound microbubbles. J Gene Med 2005; 7: 1468–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Takahashi M, Kido K, Aoi A, Furukawa H, Ono M, Kodama T. Spinal gene transfer using ultrasound and microbubbles. J Control Release 2007; 117: 267–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gambihler S, Delius M, Ellwart JW. Permeabilization of the plasma membrane of L1210 mouse leukemia cells using lithotripter shock waves. J Membr Biol 1994; 141: 267–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kodama T, Doukas AG, Hamblin MR. Shock wave‐mediated molecular delivery into cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 2002; 1542: 186–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boulikas T, Vougiouka M. Cisplatin and platinum drugs at the molecular level. Oncol Reports 2003; 10: 1663–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tennant JR. Evaluation of the trypan blue technique for determination of cell viability. Transplantation 1964; 2: 685–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aoi A, Watanabe Y, Mori S, Takahashi M, Vassaux G, Kodama T. Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase‐mediated suicide gene therapy using nano/microbubbles and ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol 2008; 34: 425–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kodama T, Doukas AG, Hamblin MR. Delivery of ribosome‐inactivating protein toxin into cancer cells with shock waves. Cancer Lett 2003; 189: 69–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kodama T, Hamblin MR, Doukas AG. Cytoplasmic molecular delivery with shock waves: importance of impulse. Biophys J 2000; 79: 1821–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kodama T, Tan PH, Offiah I et al . Delivery of oligodeoxynucleotides into human saphenous veins and the adjunct effect of ultrasound and microbubbles. Ultrasound Med Biol 2005; 31: 1683–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kojima H, Endo K, Moriyama H et al . Abrogation of mitochondrial cytochrome c release and caspase‐3 activation in acquired multidrug resistance. J Biol Chem 1998; 273: 16 647–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Abraham MC, Shaham S. Death without caspases, caspases without death. Trends Cell Biol 2004; 14: 184–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cemazar M, Miklavcic D, Mir LM et al . Electrochemotherapy of tumours resistant to cisplatin: a study in a murine tumour model. Eur J Cancer 2001; 37: 1166–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Duvshani‐Eshet M, Adam D, Machluf M. The effects of albumin‐coated microbubbles in DNA delivery mediated by therapeutic ultrasound. J Control Release 2006; 112: 156–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Taniyama Y, Tachibana K, Hiraoka K et al . Local delivery of plasmid DNA into rat carotid artery using ultrasound. Circulation 2002; 105: 1233–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Koshiyama K, Kodama T, Yano T, Fujikawa S. Structural change in lipid bilayers and water penetration induced by shock waves: molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys J 2006; 91: 2198–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee S, Anderson T, Zhang H, Flotte TJ, Doukas AG. Alteration of cell membrane by stress waves in vitro . Ultrasound Med Biol 1996; 22: 1285–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Barlogie B, Corry PM, Drewinko B. In vitro thermochemotherapy of human colon cancer cells with cis‐dichlorodiammineplatinum (II) and mitomycin C. Cancer Res 1980; 40: 1165–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weiss N, Delius M, Gambihler S, Eichholtz‐Wirth H, Dirschedl P, Brendel W. Effect of shock waves and cisplatin on cisplatin‐sensitive and – resistant rodent tumors in vivo . Int J Cancer 1994; 58: 693–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Worle K, Steinbach P, Hofstadter F. The combined effects of high‐energy shock waves and cytostatic drugs or cytokines on human bladder cancer cells. Br J Cancer 1994; 69: 58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kambe M, Ioritani N, Shirai S et al . Enhancement of chemotherapeutic effects with focused shock waves: extracorporeal shock wave chemotherapy (ESWC). In Vivo 1996; 10: 369–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yu T, Huang X, Jiang S, Hu K, Kong B, Wang Z. Ultrastructure alterations in adriamycin‐resistant and cisplatin‐resistant human ovarian cancer cell lines exposed to nonlethal ultrasound. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2005; 15: 462–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Siddik ZH. Cisplatin: mode of cytotoxic action and molecular basis of resistance. Oncogene 2003; 22: 7265–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Honda H, Zhao QL, Kondo T. Effects of dissolved gases and an echo contrast agent on apoptosis induced by ultrasound and its mechanism via the mitochondria–caspase pathway. Ultrasound Med Biol 2002; 28: 673–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lagneaux L, De Meulenaer EC, Delforge A et al . Ultrasonic low‐energy treatment: a novel approach to induce apoptosis in human leukemic cells. Exp Hematol 2002; 30: 1293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li Y, Cohen R. Caspase inhibitors and myocardial apoptosis. Int Anesthesiol Clin 2005; 43: 77–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Abdollahi A, Domhan S, Jenne JW et al . Apoptosis signals in lymphoblasts induced by focused ultrasound. FASEB J 2004; 18: 1413–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Haag P, Frauscher F, Gradl J et al . Microbubble‐enhanced ultrasound to deliver an antisense oligodeoxynucleotide targeting the human androgen receptor into prostate tumours. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2006; 102: 103–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bekeredjian R, Kuecherer HF, Kroll RD, Katus HA, Hardt SE. Ultrasound‐targeted microbubble destruction augments protein delivery into testes. Urology 2007; 69: 386–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Armstrong DK, Bundy B, Wenzel L et al . Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 34–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Suzuki R, Takizawa T, Negishi Y et al . Gene delivery by combination of novel liposomal bubbles with perfluoropropane and ultrasound. J Control Release 2007; 117: 130–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tartis MS, McCallan J, Lum AF et al . Therapeutic effects of paclitaxel‐containing ultrasound contrast agents. Ultrasound Med Biol 2006; 32: 1771–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rychak JJ, Klibanov AL, Hossack JA. Acoustic radiation force enhances targeted delivery of ultrasound contrast microbubbles: in vitro verification. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 2005; 52: 421–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Feril LB Jr, Kondo T. Biological effects of low intensity ultrasound: the mechanism involved, and its implications on therapy and on biosafety of ultrasound. J Radiat Res (Tokyo) 2004; 45: 479–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]