Abstract

The endothelin A receptor (ETAR) autocrine pathway is overexpressed in many malignancies, including nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). In this tumor, ETAR expression is an independent determinant of survival and a robust independent predictor of distant metastasis. To evaluate whether ETAR represents a new target in NPC treatment, we tested the therapeutic role of ETAR in NPC. Cell proliferation was inhibited by the ETAR‐selective antagonist ABT‐627 in two ETAR‐positive NPC cells in a dose‐dependent manner. Proliferation of ETAR‐negative NPC cells was not decreased. ETAR blockade also resulted in sensitization to cisplatin and 5‐fluorouracil‐induced apoptosis. In nude mice, ABT‐627 inhibited the growth of NPC cell xenografts. Combined treatment of ABT‐627 with the cytotoxic drug cisplatin or 5‐fluorouracil produced additive antitumor effects. The antitumor activity of ABT‐627 was demonstrated finally on an experimental lung metastasis by a reduction in the number of tumors. These results support the rationale of combining ABT‐627 with current standard chemotherapy to further improve the therapeutic ratio in the treatment of NPC. (Cancer Sci 2006; 97: 1388–1395)

Abbreviations:

- 5‐FU

5‐fluorouracil

- CI

combination index

- DDP

cisplatin

- ELISA

enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay

- ET

endothelin

- ETAR

endothelin A receptor

- ETBR

endothelin B receptor

- FTV

fractional tumor volume

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- IC50

50% growth inhibition

- IP

intraperitoneally

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- NPC

nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- PBS

phosphate‐buffered saline

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RT

reverse transcription

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor.

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is common in Southern China, with an annual incidence of 15–50 cases per 100 000 people.( 1 ) NPC is distinct from other epithelial malignancies in the head and neck region in that it affects a relatively young population and has a propensity for distant metastases.( 2 ) NPC is a radiosensitive tumor for which there is a high local control rate after radical radiotherapy. However, for patients with locoregionally advanced disease, the rate of distant metastasis is high and the 5‐year overall survival rate is poor.( 3 ) Randomized trials have confirmed that chemotherapy improves the distant metastasis control rate in patients with locoregionally advanced NPC; however, approximately 20% or more of the patients still have distant metastasis develop despite intensive chemotherapy.( 4 , 5 ) These findings underscore the need to develop novel strategies in the management of patients with advanced NPC.

The family of ET, including ET‐1, ET‐2 and ET‐3, are 21‐amino acid peptides exerting many biological effects.( 6 ) Two major receptor subtypes belonging to the G protein‐coupled family of receptors mediate ET signals: ETAR, which binds ET‐1 and ET‐2 with high affinity and ET‐3 with low affinity; and ETBR, which binds all ET isopeptides with equal affinity.( 7 ) ET‐1, which is the most common circulating form of ET, is produced by many epithelial tumors.( 8 ) ET‐1 induces cell proliferation directly or synergistically with other growth factors that are relevant in cancer progression. Engagement of ETAR by ET‐1 triggers activation of tumor proliferation,( 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ) VEGF‐induced angiogenesis,( 14 , 15 ) invasiveness( 16 ) and inhibition of apoptosis.( 17 , 18 ) The ET‐1–ETAR autocrine pathway has a key role in the development and progression of prostatic, ovarian and cervical cancers.( 9 ) The major relevance of ETAR in tumor development has led to an extensive search of highly selective antagonists. ABT‐627 (Atrasentan), one such antagonist, is orally bioavailable and has suitable pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles for clinical use.( 19 , 20 ) ABT‐627 has been given to cancer patients in phase II trials for prostate cancer and delayed the time to clinical and prostate‐specific antigen progression.( 21 ) Two pivotal randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multinational phase III trials are ongoing in patients with hormone‐refractory prostate cancer to verify these findings.

We reported previously that patients with advanced‐stage NPC had elevated plasma big ET‐1 levels compared with the levels in healthy control participants; high pretreatment plasma big ET‐1 levels are generally associated with post‐treatment distant failure.( 22 ) Our previous study also showed that ETAR was overexpressed in 73.9% of NPC, and ETAR expression was an independent determinant of survival and a robust independent predictor of distant metastasis.( 23 ) In the present study, we tested the therapeutic role of ETAR in NPC.

Materials and Methods

Materials. Clinical grade ABT‐627 was provided by Abbott Laboratories (Abbott Park, IL, USA). DDP was purchased from F. H. Faulding and Co. (Victoria, Australia). 5‐FU was purchased form Nantong Jinghua Pharmaceutical Co. (Jiangsu, China). DDP and 5‐FU were dissolved in normal saline.

Cell lines and culture conditions. SUNE‐1, HONE‐1 and CNE‐2 human NPC, and 293 HEK cell lines were provided by the Department of Experimental Research, Sun Yat‐Sen University Cancer Center. The histological type of the original tumor was World Health Organization (WHO) Grade 3 NPC in the three human NPC cell lines. These cell lines were cultured in RPMI‐1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction. Total cellular RNA was extracted from cell cultures using TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was synthesized using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and random hexamers. PCR was done using Taq DNA polymerase (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and a PCR 9700 System GeneAmp thermocycler (Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA, USA). The primer sets were as follows: ETAR, 5′‐CACTGGTTGGATGTGTAATC‐3′ and 5′‐GGAGATCAATGACCACATAG‐3′ and ETBR, 5′‐TCAACACGGTTGTGTCCTGC‐3′ and 5′‐ACTGAATAGCCACCAATCTT‐3′.( 24 ) GAPDH was used as an internal control, and the primer set used was 5′‐TGAAGGTCGGTGTCAACGGA‐3′ and 5′‐GATGGCATGGACTGTGGTCAT‐3′. The reaction mixture was first denatured at 95°C for 5 min. The PCR conditions used were 94°C for 50 s, 50°C for 50 s and 72°C for 1 min for 30 cycles followed by 72°C for 7 min. PCR products were visualized by ethidium bromide staining after agarose gel electrophoresis.

Evaluation of big ET‐1 secretion. Cell lines cultured in RPMI‐1640 were harvested at 80% confluence and plated at 2 × 106 cells/dish, cultured for 24 h, and then incubated in serum‐free medium for 48 h. The conditioned medium was collected, centrifuged to remove any cellular contaminants, and then stored in aliquots at −80°C until use. The cells were counted and the data were corrected to the cell number. Big ET‐1 concentrations in conditioned media were determined three times in duplicate with an ELISA kit using the reagents and protocol supplied with the sandwich enzyme immunoassay kit (Biomedica, Vienna, Austria). This assay, as reported by the manufacturer, is specific for human big ET‐1.

In vitro cell growth assay. Cell lines cultured in RPMI‐1640 were harvested at 80% confluence and plated at 5 × 104 cells/well in 12‐well plates, cultured for 24 h, and then incubated in serum‐free medium for 72 h with increasing concentrations (0.25–10 µM) of the selective non‐peptide ETAR antagonist, ABT‐627. Total cells were trypsinized and resuspended, and the cell numbers were counted using a cell counter. The experiments were carried out in triplicate and repeated twice.

The combined effect of ABT‐627 and DDP or 5‐FU treatment was analyzed by median‐effect analysis according to the method of Chou and Talalay.( 25 ) Three sets of experiments were carried out for each drug combination, one with the combination of ABT‐627 and DDP or 5‐FU and one set with each drug alone. CI values were expressed at each fraction affected using CalcuSyn software (Biosoft, Cambridge, UK): CI < 1 indicates synergism, CI = 1 indicates additivity, and CI > 1 indicates antagonism of the interaction. The linear regression coefficient was generated automatically for each assay.

Apoptosis assay. To detect cell death via apoptosis induced by treatment with ABT‐627 alone and in combination with DDP or 5‐FU in NPC cells, a cell death detection ELISA assay kit (Cell Death Detection ELISA Plus; Roche Applied Science, Nutley, NJ, USA) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 5 × 104 cells/well were seeded into 12‐well plates and serum‐starved for 24 h. After a 48‐h treatment, cells floating in the supernatants and those attached to the dish were incubated in lysis buffer for 30 min at room temperature. After spinning for 10 min at 200g, the DNA content of each sample was determined. Equal amounts of DNA (in 20 L) were added to each well (three wells per condition) coated with antihistone antibody and incubated with an additional 80 µL of anti‐DNA peroxidase immunogen under gentle shaking conditions for 2 h at room temperature. After washing and revelation with peroxidase substrate, the samples’ absorbances were measured at 405 nm against substrate‐containing wells as blanks. The experiments were carried out in quadruplicate and repeated twice.

Tumor cell xenografts. BALB/c nude mice (nu/nµ), 6–8 weeks of age, were purchased from the Experimental Animal Center at the Sun Yat‐Sen University (Guangzhou, China). Mice were given injections subcutaneously into one flank with 5 × 106 viable HONE‐1 cells, as determined by trypan blue staining, which were resuspended in 200 µL PBS. Palpable tumors were detected 10 days after cell injection. Tumor volume and bodyweight were measured twice weekly. Tumor volume was calculated using the formula π/6 × ([length + width]/2)3.( 26 ) After 41 days, the mice were killed under anesthesia; the tumors were excised and weighted and necropsy was done. All animal work was carried out under protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Sun Yat‐Sen University.

Experimental protocol. ABT‐627 dissolved in 0.25 M NaHCO3 at 2 mg/kg/day was administrated i.p. for 21 days, starting at various times after the xenograft. Control mice were given injections in the same way with 200 µL of 0.25 M NaHCO3. To determine the effects of the combination of ABT‐627 and cytotoxic drugs, additional groups of mice were treated i.p. for 21 days with ABT‐627 (2 mg/kg/day), alone or in combination with DDP (5 mg/kg on day 1 of each week for 3 weeks), or with 5‐FU (20 mg/kg on days 1–5) starting 10 days after tumor transplant when a palpable mass was present. The synergistic effect of ABT‐627 and DDP or 5‐FU on NPC growth was analyzed by the fractional product method.( 27 )

Experimental lung metastasis model. Cells were washed and resuspended in PBS. Subsequently, a single‐cell suspension containing 106 SUNE‐1 cells (high metastatic potential cell line) in 100 µL PBS was injected into the lateral tail vein of 6–8‐week‐old nude mice. Twelve mice were divided into two groups, the ABT‐627‐treated group (n = 6) and the control group (n = 6). Treatments were started the day after injection of SUNE‐1 cells. ABT‐627‐treated mice received i.p. injections of ABT‐627 (2 mg/kg/day) for 21 days; control mice were given injections of drug vehicle in the same way. Mice were killed after 5 weeks as our preliminary study in this animal model indicated that SUNE‐1 develop numerous lung metastasis nodules by 5 weeks. The lungs were dissected out, infused with 15% India ink intratracheally, and fixed in Fekete's solution. Visible lung metastases were counted using a dissecting microscope.

Statistical analysis. Statistical evaluations of the data were made by the two‐sided Student's test with Bonferroni corrections. Time course of tumor growth was compared across the treatment groups with the use of two‐way ANOVA, with group and time as the variables. Survival curves of tumor‐bearing nude mice were done using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using Log‐rank analysis. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 10.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA), and all P‐values that were two‐sided at a value of 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

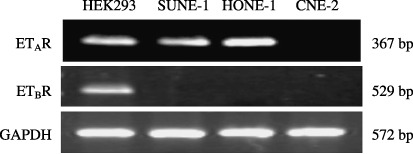

Analysis of ETAR and ETBR mRNA expression by RT‐PCR and analysis of ET‐1 production in NPC cell lines. Reverse transcription–PCR was carried out to evaluate the mRNA expression of ETAR and ETBR in three human NPC cell lines compared with the positive‐control cell line HEK 293. The PCR products were separated on a 1% agarose gel. As a control, the three human NPC cell lines were measured for expression of GAPDH. ETAR was expressed by SUNE‐1 and HONE‐1 but not CNE‐2 cells. ETBR was not produced by any of the cell lines investigated (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Endothelin A receptor (ETAR), endothelin B receptor (ETBR) and glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNAs detected by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) cell lines. Polymerase chain reaction products of 367 bp for ETAR, 529 bp for ETBR and 572 bp for GAPDH were visualized using ethidium bromide. Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cell line was used as an ETAR‐ and ETBR‐positive control. ETAR was expressed only by SUNE‐1 and HONE‐1, whereas none of the NPC cell lines produced ETBR.

The three NPC cell lines, HONE‐1, SUNE‐1 and CNE‐2, released big ET‐1 in the culture media. The concentrations of big ET‐1 in the conditioned media at 48 h were 274 pg/mL/106 cells from HONE‐1, 187 pg/mL/106 cells from SUNE‐1, and 62 pg/mL/106 cells from CNE‐2.

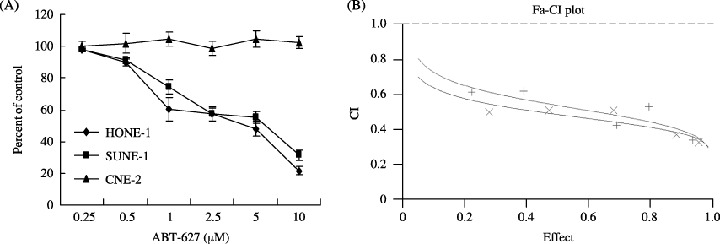

In vitro effects of ABT‐627 in NPC cells. To evaluate the effect of ABT‐627 on the proliferation of NPC cells, we used three established cell lines. HONE‐1 and SUNE‐1 cells express ETAR mRNA and secrete high levels of big ET‐1. We treated these NPC cells with different concentrations of ABT‐627 for 72 h and measured the effect of ABT‐627 on cell viability. Treatment with ABT‐627 at doses ranging between 0.25 and 10 µM determined a dose‐dependent inhibition of spontaneous growth rate with a comparable IC50 of ∼1 µM in HONE‐1 and SUNE‐1 cell lines. The same dosage of the antagonist ABT‐627 had no effect on CNE‐2 cells, which was as expected because of the absence of ETAR in this cell line (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

(A) Effect of ABT‐627 on the spontaneous growth rate of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell lines. HONE‐1, SUNE‐1 and CNE‐2 were seeded at 5 × 104 cells/well in 12‐well plates and incubated in serum‐free medium for 72 h with different concentrations of ABT‐627. Cell numbers were measured using a cell counter. Data are the average of two different experiments, each carried out in triplicate. Error bars, mean ± SD. (B) Combination index (CI) plots of ABT‐627–cisplatin (DDP) (×) or ABT‐627–5‐fluorouracil (5‐FU) (+) combination in HONE‐1 cells. The two drugs were combined simultaneously. Combination analysis was carried out using the method described by Chou and Talalay. (25 ) Fa, fraction affected. CI = 1.0

The effect of DDP and 5‐FU as single agents on the growth of the HONE‐1 cells was first assessed. DDP inhibits HONE‐1 cell growth with an IC50 of 3.25 µM for 72 h exposure. Treatment with 5‐FU causes growth inhibition with an IC50 of 7.93 µM (Table 1). To evaluate potential synergy, we added combinations of ABT‐627 and DDP or 5‐FU at constant ratios with respect to their respective IC50 concentrations. Treatment with ABT‐627 and DDP or 5‐FU demonstrated clear evidence of synergy because the CI was <1 in all cases, and very often between 0.3 and 0.7 (Fig. 2B).

Table 1.

Dose–effect analyses of ABT‐627 with cytotoxic drugs in HONE‐1 human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells

| Regimen | Ratio † | Drug | IC50 (µM) | m | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single drug | – | ABT‐627 | 1.81 ± 0.16 | 1.15 ± 0.02 | 0.9921 ± 0.0046 |

| – | DDP | 3.25 ± 0.60 | 1.35 ± 0.05 | 0.9913 ± 0.0070 | |

| – | 5‐FU | 7.93 ± 1.75 | 1.18 ± 0.16 | 0.9876 ± 0.0057 | |

| ABT‐627 + DDP | ABT‐627 | 0.41 ± 0.26 | |||

| DDP | 0.83 ± 0.32 | ||||

| 1:2 | ABT‐627 + DDP | 1.47 ± 0.10 | 0.9928 ± 0.0053 | ||

| ABT‐627 + 5‐FU | ABT‐627 | 0.51 ± 0.42 | |||

| 5‐FU | 2.02 ± 0.81 | ||||

| 1:4 | ABT‐627 + 5‐FU | 0.51 ± 0.12 | 0.9922 ± 0.0011 |

The combination ratio was approximately equal to the IC50 ratio of the component drugs (i.e. close to their equipotency ratio). Values are the means of three independent experiments ± SD. 5‐FU, 5‐fluorouracil; DDP, cisplatin; IC50, 50% growth inhibition; m, slope of the median‐effect plot; r, linear correlation coefficient of the median‐effect plot.

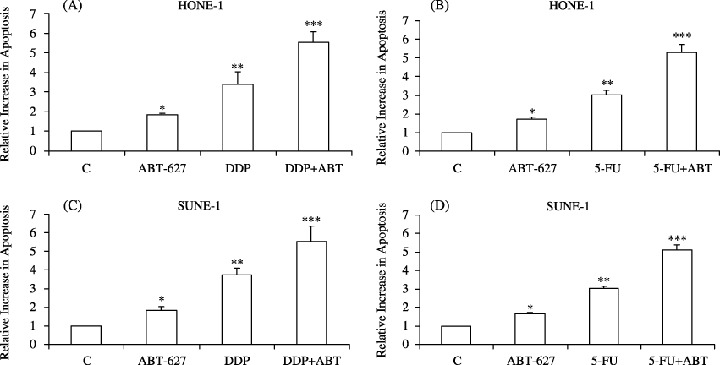

To determine whether the antiproliferative effect of ABT‐627 resulted in the induction of programmed cell death, we evaluated the percentage of dying cells in ABT‐627‐treated and control cultures. As shown in Fig. 3, ABT‐627 (1 µM) treatment increased the percentage of apoptotic HONE‐1 and SUNE‐1 NPC cells after 48 h of treatment (P < 0.05). The addition of ABT‐627 significantly increased DDP‐ and 5‐FU‐induced apoptosis (P < 0.0001) in both cell lines. These results established that ETAR‐activated autocrine survival pathways were affected by treatment with ABT‐627.

Figure 3.

Induction of apoptosis by treatment with ABT‐627 alone and in combination with the indicated cytotoxic drugs in (A,B) HONE‐1 or (C,D) SUNE‐1 cells. Cells were serum‐starved for 24 h and then untreated or treated for 48 h with ABT‐627 alone (1 µM), with cisplatin (DDP) alone (20 µM) or with a combination of the two, or with 5‐fluorouracil (5‐FU) alone (40 µM) alone or in combination with ABT‐627. Data are expressed in arbitrary units with relative increase compared with untreated cells considered as 1. Data represent the average of quadruplicate determinations of two separate experiments; error bars, mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 vs controls; **P < 0.001 vs controls; ***P < 0.0001 vs controls.

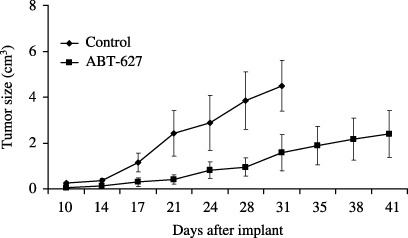

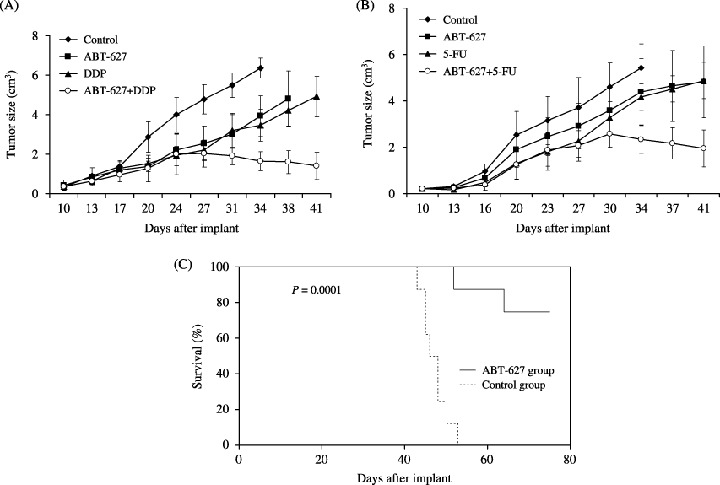

Inhibition of tumor growth in experimental models. In the present study, a 2 mg/kg/day dose of ABT‐627 was chosen because it corresponded to that used in human clinical trials.( 20 ) ABT‐627 treatment at 2 mg/kg/day for 21 days was started the same day as tumor cell transplantation. Administration of ABT‐627 significantly inhibited the growth of HONE‐1 human NPC compared with the controls, resulting in a 58.2% decrease in tumor volume on day 31 after tumor injection (P < 0.001 compared with control; Fig. 4). ABT‐627 treatment was generally well tolerated with no detectable signs of acute or delayed toxicity.

Figure 4.

ABT‐627 treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma xenografts. Nude mice were given injections of 5 × 106 HONE‐1 cells. ABT‐627 treatment at 2 mg/kg/day for 21 days was started the same day as tumor cell transplantion. The control animals were given injections of the vehicle, 0.25 M NaHCO3. Each group consisted of eight mice. Error bars, ±SD.

DDP and 5‐FU are regarded as first‐line cytotoxic drugs for chemotherapy of NPC by many investigators.( 28 , 29 ) The in vivo combination effect of ABT‐627 and chemotherapeutic agent was examined. The treatment was started 10 days after HONE‐1 cells were inoculated, when they had reached a mean size of approximately 0.4 cm3. For the combined therapy, ABT‐627 (2 mg/kg/day) was given i.p. for 21 days in combination with DDP (5 mg/kg on day 1 of each week for 3 weeks) or 5‐FU (20 mg/kg on days 1–5). In the experiment shown in Fig. 5A, treatment with ABT‐627 produced a 38.1% inhibition of HONE‐1 tumor growth on day 34 after tumor injection (P = 0.007 compared with control). The tumor growth suppression by treatment with ABT‐627 was comparable with that achieved by treatment with DDP (P = 0.959). More marked tumor growth inhibition (74.2% of control) was elicited by combined treatment with ABT‐627 and DDP (P < 0.001 compared with control). The time course comparison of tumor growth curves by two‐way ANOVA with group and time as variables showed that the group‐by‐time interaction for tumor growth was statistically significant (P < 0.001; Fig. 5A). Furthermore, the tumor growth inhibition obtained with combination treatment persisted for up to 10 days after the termination of treatment (Fig. 5A). Table 2 summarizes the relative tumor volume of control and treated groups at three different time points. With time, there was a progressive improvement in antitumor activity. Combination therapy with ABT‐627 and DDP showed more than an additive effect on tumor growth inhibition. On day 34, there was 1.31‐fold improvement in antitumor activity in the combination group compared with the expected additive effect.

Figure 5.

Antitumor activity of ABT‐627 treatment on established HONE‐1 human nasopharyngeal carcinoma xenografts. Mice were given injections of 5 × 106 HONE‐1 cells subcutaneously in the dorsal flank. (A) Combination therapy with ABT‐627 and cisplatin (DDP). After 10 days (average tumor size, 0.4 cm3), the mice were treated intraperitoneally for 21 days with vehicle (control), ABT‐627 (2 mg/kg/day) alone, DDP alone (5 mg/kg on day 1 of each week for 3 weeks), or ABT‐627 in combination with DDP. Each group consisted of six mice. (B) Combination therapy with ABT‐627 and 5‐fluorouracil (5‐FU). After 10 days (average tumor size, 0.4 cm3), the mice were treated intraperitoneally for 21 days with vehicle (control), ABT‐627 (2 mg/kg/day) alone, 5‐FU alone (25 mg/kg on days 1–5), or ABT‐627 in combination with 5‐FU. Each group consisted of nine mice. Error bars, ±SD. (C) Effects of two cycles of ABT‐627 treatment on the survival of HONE‐1 tumor‐bearing mice. HONE‐1 cells (5 × 106) were inoculated into nude mice. Each group consisted of eight mice. Ten days after a palpable tumor was present, treatment with ABT‐627 at 2 mg/kg/day for 21 days was started. The control animals were treated with the vehicle, 0.25 M NaHCO3. Seven days after the end of the first treatment, a new treatment cycle with the same dosage and time was undertaken. Survival analysis was done using the Kaplan–Meier method and log‐rank tests.

Table 2.

Combination therapy with ABT‐627 and cisplatin (DDP)

| Day ‡ | FTV relative to untreated controls † | Combination treatment | Ratio of expected FTV/observed FTV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABT‐627 | DDP | Expected § | Observed | ||

| 27 | 0.5344 | 0.4601 | 0.2459 | 0.4229 | 0.5814 |

| 31 | 0.5497 | 0.5801 | 0.3189 | 0.3492 | 0.9132 |

| 34 | 0.6191 | 0.5468 | 0.3385 | 0.2583 | 1.3103 |

Fractional tumor volume (FTV) = (mean tumor volume experimental)/(mean tumor volume control);

‡ day after tumor cell transplantation;

(mean FTV of ABT‐627) × (mean FTV of DDP). A ratio >1 indicates a synergistic effect, and a ratio <1 indicates a less than additive effect.

In the experiment shown in Fig. 5B, ABT‐627 treatment displayed antitumor activity against established HONE‐1 cancer xenografts in nude mice (25.8% reduction in tumor volume on day 34 after tumor injection; P = 0.025). The extent of tumor inhibition was similar to that obtained using the cytotoxic drug 5‐FU (P = 0.957). The combination of ABT‐627 and 5‐FU significantly inhibited the growth of HONE‐1 human NPC xenografts compared with the control group (56.9% reduction in tumor volume; P < 0.001). The time course comparison of tumor growth curves by two‐way ANOVA with group and time as variables showed that the group‐by‐time interaction for tumor growth was statistically significant (P < 0.001; Fig. 5B). Furthermore, the tumor growth inhibition obtained with combination treatment persisted for up to 10 days after termination of treatment (Fig. 5B). Table 3 summarizes relative tumor volume of control and treated groups at three different time points. With time, there was a progressive improvement in antitumor activity. Combination treatment with ABT‐627 and 5‐FU showed more than an additive effect on tumor growth inhibition. On day 34, there was 1.43‐fold improvement in antitumor activity in the combination group compared with the expected additive effect.

Table 3.

Combination therapy with ABT‐627 and 5‐fluorouracil (5‐FU)

| Day ‡ | FTV relative to untreated controls † | Combination treatment | Ratio of expected FTV/observed FTV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABT‐627 | 5‐FU | Expected § | Observed | ||

| 27 | 0.7835 | 0.6106 | 0.4784 | 0.5562 | 0.8601 |

| 30 | 0.7788 | 0.7097 | 0.5527 | 0.5569 | 0.9925 |

| 34 | 0.8085 | 0.7656 | 0.6191 | 0.4308 | 1.4368 |

Fractional tumor volume (FTV) = (mean tumor volume experimental)/(mean tumor volume control);

‡ day after tumor cell transplantation;

(mean FTV of ABT‐627) × (mean FTV of 5‐FU). A ratio >1 indicates a synergistic effect, and a ratio <1 indicates a less than additive effect.

In the survival study, the survival time in mice treated with two cycles of ABT‐627 (at 7‐day intervals) was significantly longer than in mice given control vehicle. After 75 days, the survival rate in the control group was 0%, compared with 75% in the mice treated with two cycles of ABT‐627 (P = 0.0001; Fig. 5C).

Inhibitory effect of ABT‐627 on lung metastasis. Table 4 summarizes the inhibitory effect of ABT‐627 on lung metastasis. The number of metastatic lung nodules in the mice treated with ABT‐627 was significantly lower than that in the control mice (P = 0.001; Table 4). The average number of metastatic nodules in the control group was 49.5 ± 21.1. In the ABT‐627‐treated group, this number was only 7.0 ± 3.8. Among the six mice in the ABT‐627‐treated group, the highest number of metastatic nodules was 11 and one mouse had no metastatic nodules on the lung surface. Based on the results of this in vivo study, ABT‐627 clearly inhibits experimental lung metastasis in nude mice.

Table 4.

Inhibitory effect of ABT‐627 on lung metastasis

| Group | Number of metastatic nodules | Mean ± SD* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse 1 | Mouse 2 | Mouse 3 | Mouse 4 | Mouse 5 | Mouse 6 | ||

| Control | 24 | 35 | 43 | 47 | 66 | 82 | 49.5 ± 21.1 |

| ABT‐627 | 0 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 7.0 ± 3.8 |

P = 0.001.

Discussion

Increased ETAR expression has been reported in a broad range of human cancers, including prostate,( 30 ) ovarian,( 12 ) breast,( 31 ) colon,( 32 ) lung,( 33 ) cervical,( 13 ) renal( 34 ) and thyroid gland.( 35 ) Overexpression of ETAR is generally associated with a more malignant phenotype. In cancer of the prostate and breast, ETAR overexpression is associated with aggressive tumor behavior and a worse prognosis.( 30 , 31 ) In our previous study,( 23 ) ETAR expression was found in 73.9% of patients with NPC. Correlative analysis showed that ETAR expression was a strong, independent prognostic indicator of overall survival and relapse‐free survival rate. Analysis of the patterns of relapse revealed a clinically relevant finding that ETAR expression was a robust predictor for distant metastasis but not for locoregional relapse. Patients with high ETAR expression had a significantly higher incidence of distant metastasis than patients with low ETAR expression. It may be the case therefore that overexpression of ETAR in NPC tissue plays an important role in the initiation or promotion of tumor cell metastasis by enhancing the response of these cells to the know effects of ET‐1.( 36 )

Changes in the homeostasis of growth factor‐induced physiological signaling may lead to unbalanced cell growth. Research has shown that ETAR signaling not only increases cell proliferation, but also regulates a range of processes that are essential for tumor progression, including cell motility, cell adhesion, tumor invasion, cell survival, angiogenesis, matrix remodeling and bone deposition in skeletal metastases.( 37 ) Direct mechanistic evidence of the role of ETAR in various malignancies supports the concept that ETAR antagonists may significantly revert the malignant phenotype.( 38 ) The use of ETAR antagonists seems to be an attractive approach because the selective inhibition of ETAR reduces both tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis in different tumor types. Rosano et al. established the reduction of cell proliferation and angiogenesis by applying an ETAR antagonist (ABT‐627) to ovarian cancer.( 39 ) Similar antitumoral effects have been achieved in prostate and cervical cancer.( 40 , 41 )

The present study showed that ET‐1 is produced by all three of the NPC cell lines used, and mRNA expression of ETAR is limited to some cell lines (SUNE‐1 and HONE‐1, not CNE‐2). ETBR tends not to be expressed, probably due to gene silencing through hypermethylation of the 5′‐CpG island of Endothelin Receptor B gene (EDNRB).( 42 ) In our analysis we successfully confirmed this, and showed that ETBR is not produced by the NPC cell lines investigated. In vitro assays demonstrated that the ETAR antagonist ABT‐627 reduces proliferation of human NPC cells expressing ETAR. The inhibitory effect of ABT‐627 was absent in CNE‐2 cells, a NPC cell line not expressing ETAR, indicating that only ETAR‐expressing NPC cells respond to growth inhibition by ABT‐627.

ABT‐627 treatment inhibited cell proliferation and increased programmed cell death in NPC cell lines, indicating that ETAR mediates an ET‐1 proliferative signal. The overproduction of ET‐1 and the upregulation of the autocrine loop mediated by ETAR in NPC cells indicates that this receptor could be used as a target for therapy. Consequent to this hypothesis, compounds that antagonize the action of ET‐1 by blocking ETAR would be able to affect the growth of NPC xenografts in nude mice.

In ovarian carcinoma xenograft models,( 39 ) tumor growth was inhibited in ABT‐627‐treated mice with an efficacy similar to paclitaxel; this effect was associated with a significant decrease in microvessel density, expression of VEGF and MMP‐2, and increased apoptosis. The combination of atrasentan and paclitaxel led to increased apoptosis and reduced neovascularization, thereby causing tumor regression. Wulfing et al. reported that expression of ETAR predicts unfavorable response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced breast cancer.( 43 )

DDP and 5‐FU are regarded as first‐line cytotoxic drugs for chemotherapy of NPC by many investigators.( 28 , 29 ) In the present study, we investigated the action of the ETAR antagonist ABT‐627 on the growth of NPC xenografts in monotherapy as well as in association with the chemotherapeutic compounds DDP and 5‐FU. Early treatment (at day 0 from cell injection) as well as late treatment (at day 10, when the tumors were already palpable) with the same dosage (2 mg/kg/day) were effective in reducing the size of tumors produced by HONE‐1 cells and in delaying tumor growth. Tumor growth was inhibited in ABT‐627‐treated mice with an efficacy similar to DDP or 5‐FU in well‐established HONE‐1 xenografts. This treatment was generally well tolerated, with no detectable signs of acute or delayed toxicity. More marked and prolonged tumor growth inhibition was obtained by combined treatment of ABT‐627 with DDP or 5‐FU (P < 0.001).

In the present study, ABT‐627 and DDP or 5‐FU were given together in a fixed schedule and dose. Therefore, the observed synergism can be further improved by modulating dosage and frequency of administration based on pharmacokinetics, distribution, and bioavailability.

Endothelin‐1, acting through the ETAR, induces mRNA transcription, zymogen secretion and pro‐enzyme activation of two families of metastasis‐related proteinases, MMP and the urokinase‐type Plasminogen Activator (uPA) system.( 14 , 16 , 44 , 45 ) In a study by Rosano et al. the addition of an ETAR antagonist blocked ET‐1‐induced MMP‐dependent invasion of ovarian carcinoma cells.( 16 ) Tumor‐produced ET‐1 may also have a major role in the establishment of osteoblastic bone metastases in prostate and breast cancer.( 46 , 47 ) In the present study, the number of metastatic lung nodules in the mice treated with ABT‐627 was significantly lower than that in the control mice in the experimental lung metastasis model (P = 0.001). ABT‐627 clearly inhibits experimental lung metastasis in nude mice. Recently, it was shown that the endothelin axis was a target of the lung metastasis suppressor gene RhoGDI2, and ABT‐627 treatment resulted in a dramatic reduction in lung metastases, similar to the effect of re‐expressing RhoGDI2 in lung metastatic bladder carcinoma cells.( 48 )

In summary, the current study demonstrated that a selective antagonist of the ETAR, ABT‐627, was able to inhibit the in vivo growth and metastasis of NPC cells and to potentiate cytotoxic treatment in combination with DDP or 5‐FU. In view of these findings, future studies on the clinical applications of ABT‐627 in combination with current standard chemotherapy following radiotherapy for ETAR‐positive NPC seems to be warranted.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the State Key Laboratory of Oncology in South China (No. 985‐2, H. Q. Mai) and the Key Subject Foundation of Guangdong Provincial Health Bureau (No. 2003‐13, M. H. Hong). We gratefully acknowledge Abbott Oncology GPRD for kindly providing the ABT‐627; Professor Hui‐Min Wang, Professor Mu‐Sheng Zeng, Ming‐Fan Zhu and Hua‐Ping Li for help with the experimental studies.

References

- 1. Min HQ. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. In: Gun GY, ed. Epidemiology. Beijing: People's Medical Press, 1996; 280–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Altun M, Fandi A, Dupuis O, Cvitkovic E, Krajina Z, Eschwege F. Undifferentiated nasopharyngeal cancer (UCNT): current diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1995; 32: 859–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mai HQ. Prognosis and prognostic factors. In: Min HQ, Hong MH, Guo X, eds. Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Beijing: Chinese Medical Press, 2003; 379–83. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Langendijk JA, Leemans CR, Buter J, Berkhof J, Slotman BJ. The additional value of chemotherapy to radiotherapy in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a meta‐analysis of the published literature. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 4604–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wee J, Tan EH, Tai BC et al. Randomized trial of radiotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union against cancer stage III and IV nasopharyngeal cancer of the endemic variety. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 6730–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yanagisawa M, Kurihara H, Kimura S et al. A novel potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by vascular endothelial cells. Nature 1988; 332: 411–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Takuwa Y et al. Cloning of a cDNA encoding a non‐isopeptide‐selective subtype of the endothelin receptor. Nature 1990; 348: 732–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kusuhara M, Yamaguchi K, Nagasaki K et al. Production of endothelin in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res 1990; 50: 3257–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bagnato A, Catt KJ. Endothelins as autocrine regulators of tumor cell growth. Trends Endocrinol Metab 1998; 9: 378–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pagotto U, Arzberger T, Hopfner U et al. Expression and localization of endothelin‐1 and endothelin receptors in human meningiomas. Evidence for a role in tumoral growth. J Clin Invest 1995; 96: 2017–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wu‐Wong JR, Chiou W, Magnuson SR, Bianchi BR, Lin CW. Human astrocytoma U138MG cells express predominantly type‐A endothelin receptor. Biochim Biophys Acta 1996; 1311: 155–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bagnato A, Salani D, Di Castro V et al. Expression of endothelin‐1 and endothelin A receptor in ovarian carcinoma: evidence for an autocrine role in tumor growth. Cancer Res 1999; 59: 720–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Venuti A, Salani D, Manni V, Poggiali F, Bagnato A. Expression of endothelin‐1 and endothelin A receptor in HPV‐associated cervical carcinoma: new potential targets for anticancer therapy. FASEB J 2000; 14: 2277–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Salani D, Taraboletti G, Rosano L et al. Endothelin‐1 induces an angiogenic phenotype in cultured endothelial cells and stimulates neovascularization in vivo . Am J Pathol 2000; 157: 1703–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Salani D, Di Castro V, Nicotra MR et al. Role of endothelin‐1 in neovascularization of ovarian carcinoma. Am J Pathol 2000; 157: 1537–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rosano L, Varmi M, Salani D et al. Endothelin‐1 induces tumor proteinase activation and invasiveness of ovarian carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 2001; 61: 8340–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wu‐Wong JR, Chiou WJ, Wang J. Extracellular signal‐regulated kinases are involved in the antiapoptotic effect of endothelin‐1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2000; 293: 514–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nelson JB, Udan MS, Guruli G, Pflug BR. Endothelin‐1 inhibits apoptosis in prostate cancer. Neoplasia 2005; 7: 631–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carducci MA, Nelson JB, Bowling MK et al. Atrasentan, an endothelin‐receptor antagonist for refractory adenocarcinomas: safety and pharmacokinetics. J Clin Oncol 2002; 20: 2171–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Verhaar MC, Grahn AY, Van Weerdt AW et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic effects of ABT‐627, an oral ETA selective endothelin antagonist, in humans. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2000; 49: 562–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carducci MA, Padley RJ, Breul J et al. Effect of endothelin‐A receptor blockade with atrasentan on tumor progression in men with hormone‐refractory prostate cancer: a randomized, phase II, placebo‐controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 679–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mai HQ, Zeng ZY, Zhang CQ et al. Elevated plasma big ET‐1 is associated with distant failure in patients with advanced‐stage nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer 2006; 106: 1548–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mai HQ, Zeng ZY, Zhang HZ et al. Correlation of endothelin A receptor expression to prognosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Chin J Cancer 2005; 24: 611–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pekonen F, Nyman T, Ammala M, Rutanen EM. Decreased expression of messenger RNAs encoding endothelin receptors and neutral endopeptidase 24.11 in endometrial cancer. Br J Cancer 1995; 71: 59–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chou TC, Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose–effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzyme Regul 1984; 22: 27–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jacobsen GK, Povlsen CO, Rygaard J. Immunological reconstitution of nude mice transplanted with human malignant tumours. Tokai J Exp Clin Medical 1983; 8: 513–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yokoyama Y, Dhanabal M, Griffioen AW, Sukhatme VP, Ramakrishnan S. Synergy between angiostatin and endostatin: inhibition of ovarian cancer growth. Cancer Res 2000; 60: 2190–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Al‐Sarraf M, McLaughlin PW. Nasopharynx carcinoma: choice of treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1995; 33: 761–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ma J, Mai HQ, Hong MH et al. Results of a prospective randomized trial comparing neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus radiotherapy with radiotherapy alone in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 1350–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gohji K, Kitazawa S, Tamada H, Katsuoka Y, Nakajima M. Expression of endothelin receptor a associated with prostate cancer progression. J Urol 2001; 165: 1033–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wulfing P, Diallo R, Kersting C et al. Expression of endothelin‐1, endothelin‐A, and endothelin‐B receptor in human breast cancer and correlation with long‐term follow‐up. Clin Cancer Res 2003; 9: 4125–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ali H, Dashwood M, Dawas K, Loizidou M, Savage F, Taylor I. Endothelin receptor expression in colorectal cancer. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2000; 36: S69–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ahmed SI, Thompson J, Coulson JM, Woll PJ. Studies on the expression of endothelin, its receptor subtypes, and converting enzymes in lung cancer and in human bronchial epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2000; 22: 422–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Douglas ML, Richardson MM, Nicol DL. Endothelin axis expression is markedly different in the two main subtypes of renal cell carcinoma. Cancer 2004; 100: 2118–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Donckier JE, Michel L, Van Beneden R, Delos M, Havaus X. Increased expression of endothelin‐1 and its mitogenic receptor ETA in human papillary thyroid carcinoma. Clin Endocrinol 2003; 59: 354–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Grant K, Loizidou M, Taylor I. Endothelin‐1: a multifunctional molecule in cancer. Br J Cancer 2003; 88: 163–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nelson J, Bagnato A, Battistini B, Nisen P. The endothelin axis: emerging role in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2003; 3: 110–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bagnato A, Natali PG. Endothelin receptors as novel targets in tumor therapy. J Transl Med 2004; 2: 16–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rosano L, Spinella F, Salani D et al. Therapeutic targeting of the endothelin A receptor in human ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res 2003; 63: 2447–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lassiter LK, Carducci MA. Endothelin receptor antagonists in the treatment of prostate cancer. Semin Oncol 2003; 30: 678–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bagnato A, Cirilli A, Salani D et al. Growth inhibition of cervix carcinoma cells in vivo by endothelin A receptor blockade. Cancer Res 2002; 62: 6381–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lo KW, Tsang YS, Kwong J, To KF, Teo PM, Huang DP. Promoter hypermethylation of the EDNRB gene in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Cancer 2002; 98: 651–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wulfing P, Tio J, Kersting C et al. Expression of endothelin‐A‐receptor predicts unfavourable response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced breast cancer. Br J Cancer 2004; 91: 434–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rosano L, Salani D, Di Castro V, Spinella F, Natali PG, Bagnato A. Endothelin‐1 promotes proteolytic activity of ovarian carcinoma. Clin Sci 2002; 103: S306–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Spinella F, Rosano L, Di Castro V, Natali PG, Bagnato A. Endothelin‐1 induces vascular endothelial growth factor by increasing hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1α in ovarian carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 27850–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nelson JB, Hedican SP, George DJ et al. Identification of endothelin‐1 in the pathophysiology of metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Nat Med 1995; 1: 944–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yin JJ, Mohammad KS, Kakonen SM et al. A causal role for endothelin‐1 in the pathogenesis of osteoblastic bone metastases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100: 10954–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Titus B, Frierson HF Jr, Conaway M et al. Endothelin axis is a target of the lung metastasis suppressor gene RhoGDI2. Cancer Res 2005; 65: 7320–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]