Abstract

It has been conventionally accepted that primary androgen depletion therapy (PADT) is effective only as a palliative treatment against localized prostate cancer (LPC) and locally advanced prostate cancer (LAPC), like its effect against advanced (metastatic) prostate cancer. In Japan, however, PADT has long been the treatment of choice for LPC and LAPC. The frequency of PADT being chosen to treat LPC and LAPC is also on the rise in clinical practice in the USA. Very little evidence to support this trend has so far been available. A study on the outcomes of endocrine therapy is currently being conducted in Japan by the Japanese Prostate Cancer Surveillance Group. Results of several domestic and overseas randomized trials have recently been published, and evidence for the efficacy of PADT in LPC and LAPC has been accumulating. The effectiveness of PADT in LAPC, in particular, is worthy of attention. There is a possibility that therapeutic strategies for LPC and LAPC may change dramatically in the near future. (Cancer Sci 2006; 97: 243 – 247)

Therapeutic strategies aimed at radical cure are adopted, in principle, for localized prostate cancer (LPC). Likewise, aggressive treatment is carried out for some cases of locally advanced prostate cancer (LAPC) in the hope of achieving a radical cure. The AUA Guidelines,( 1 ) the National Cancer Institute‐Physician data query (NCI‐PDQ) of the USA,( 2 ) and the EAU Guidelines( 3 ) do not recommend primary androgen depletion therapy (PADT) for the majority of LPC or LAPC cases. However, data on the current treatment of prostate cancer in Japan shows that PADT is chosen to treat LPC and LAPC in an extremely high proportion of cases.( 4 ) A compilation by Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavour (CaPSURE) of the USA also shows an increase in recent years in the proportion of LPC and LAPC patients for whom PADT is being selected.( 5 ) Until recently, androgen depletion therapy (ADT) was believed to be a palliative treatment and not by any means a radical therapy. It is important to investigate if this view is changing, and if the development of drugs associated with ADT in recent years is prompting such shifts. This is because, with prostate‐specific antigen (PSA) screening becoming more widespread, a marked ‘stage migration’ has occurred, and the proportion of LPC cases, in particular, has risen sharply. As a result, there is now growing criticism that PADT is being selected without clear evidence.

Historical background of androgen depletion therapy

Prostate cancer was diagnosed histologically for the first time in the mid‐19th century. In those days prostate cancer is said to have been an extremely rare disease. The effects of endocrine therapy (orchiectomy or administration of estrogen) against prostate cancer were first reported in 1941,( 6 ) and Huggins received a Nobel Prize for his achievements 25 years later in 1966. Needless to say, PSA had not been discovered at that time, and almost all cases of prostate cancer were in an advanced stage with metastasis when diagnosed. Huggins stated; ‘It is certain that, in many cases, regression of the neoplasm is not complete.’( 6 ) His understanding of advanced cancer with metastasis was correct and it remains unchanged even today. PSA was discovered in 1979 and subsequently facilitated the diagnosis of LPC.( 7 ) A dramatic ‘stage migration’ occurred and the incidence of LPC cases soared. Radical treatments such as surgery and radiation therapy flourished as a result. In particular, since Walsh released a report in 1983( 8 ) on radical prostatectomy using an anatomical approach, this operation has become widespread. What the Nobel Prize winner, Huggins, had said –‘Regression of the neoplasm is not complete’– came to be quoted, like a mantra, for LPC as well, especially in Europe and the USA. In my opinion the medical community dismissed the role of ADT in LPC and LAPC without waiting for clinical evidence. The current flood of different treatments has, I believe, come about without sufficient study of the natural history of LPC and LAPC. The phenomenon of ‘stage migration’ attributable to PSA screening occurred in Japan as well,( 9 ) a little later than in Europe and the USA, and the technique of radical prostatectomy using the anatomical approach was introduced at the same time. However, the Huggins’ mantra had relatively little effect on the Japanese medical community and PADT continued to be used, with little resistance, for numerous LPC and LAPC cases.( 10 , 11 , 12 ) The fact that cardiovascular adverse reactions to administration of estrogen, which became a serious issue in clinical trials carried out by the US Veterans Administration Cooperative Urological Research Group (VACURG),( 13 ) were relatively uncommon in Japan is believed to have played no small part in this. Another factor that caused a different response to PADT in Japan than in Western countries may have been that clinical tests conducted in Japan have shown PADT to be effective against LPC and LAPC.( 12 ) Under these circumstances, the report of Albertsen et al. on their 20‐year follow‐up study of conservative treatment for LPC( 14 ) is significant. Patients in this study received the following treatments within 6 months of being diagnosed with the disease: no treatment (58%), orchiectomy (16%), estrogen therapy (22%), and orchiectomy + estrogen therapy (4%). Their conclusion that ‘low risk’ patients had a low mortality from prostate cancer, and that they therefore did not require aggressive treatment, caused a major stir in how treatment methods should be selected, and how clinical trials should be carried out from then on. This has brought about a new challenge, namely, determining the best therapeutic strategy for ‘low risk’ patients: PADT or watchful waiting?

Current status of primary androgen depletion therapy use in newly diagnosed patients in 2000 according to the Japanese Urological Association (JUA) registration data

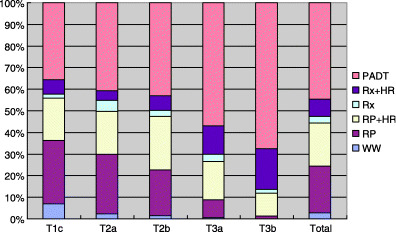

In 2000, the JUA launched a system for registering patients who were newly diagnosed with prostate cancer at institutions authorized by the JUA. The system aims to collect background factors about prostate cancer patients and to carry out a prognostic survey after a set period of time. The compilation results of 2000 were published in 2005,( 4 ) and showed that 4529 patients were registered that year. Among 4447 patients whose TNM classification was recorded, 20.26%, 39.11% and 26.83% were T1c, T2 and T3, respectively (Table 1). Fig. 1 shows a breakdown of the initial treatments these patients received. PADT was used in 40% of T1c patients and in over 50% of T2 patients.

Table 1.

T stage distribution TNM classification (5th edition, 1997) †

| T stage | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| T0 | 12 | 0.27 |

| T1a | 166 | 3.73 |

| T1b | 78 | 1.75 |

| T1c | 901 | 20.26 |

| T2a | 968 | 21.77 |

| T2b | 771 | 17.34 |

| T3a | 702 | 15.79 |

| T3b | 491 | 11.04 |

| T4 | 358 | 8.05 |

| Total | 4447 | 100 |

Cited from the Cancer Registration Committee of Japanese Urological Association.

Figure 1.

Initial therapy at each stage. HR, androgen depletion therapy; PADT, primary androgen depletion therapy; RP, radical prostatectomy; Rx, radiation therapy; WW, watchful waiting.

Trends in primary androgen depletion therapy in Japan according to Japanese Prostate Cancer Surveillance Group (J‐CaP) surveillance

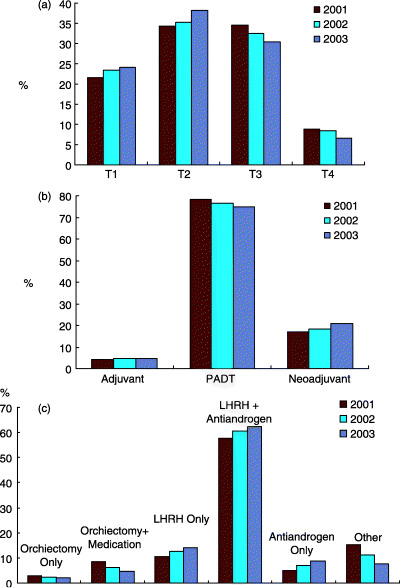

In 2001 the J‐CaP was established to study endocrine therapy in prostate cancer in Japan and to verify the outcomes prospectively.( 15 ) Subjects for the study were patients who started endocrine therapy for the first time during a particular year. A total of 7718 patients were registered in 2001; 8524 in 2002; and 8894 in 2003. As of the first half of 2003, the background factors of the majority of these patients had been analyzed and published.( 15 ) Later, a total of 25 136 patients was reached. At present, the second stage of the survey, that is, a follow‐up study of outcomes, is underway. Fig. 2 shows a breakdown for each stage and the annual changes.

Figure 2.

Japanese Prostate Cancer Surveillance Group (J‐CaP) surveillance data. (a) Percentage of patients registered in each clinical stage; (b) purpose of androgen depletion therapy (ADT); (c) method of ADT. LH‐RH, luteinizing hormone‐releasing hormone; PADT, primary androgen depletion therapy.

This surveillance data is limited. It does not show, for example, what percentage of T1 cases underwent endocrine therapy; rather, it shows that between 20% and 24% of the registered patients were T1. Based on Fig. 2b, we know that most of these patients underwent PADT, and that the majority received luteinizing hormone‐releasing hormone (LH‐RH) agonists and anti‐androgen agents concomitantly (maximal androgen blockade, MAB). From this data, along with the results of the JUA study mentioned previously, we can see that many LPC and LAPC patients in Japan are treated with endocrine therapy. J‐CaP surveillance is expected to shed light on the outcomes of endocrine therapy in the near future.

Status of primary androgen depletion therapy in localized prostate cancer and locally advanced prostate cancer as reported from US CaPSURE surveillance

The US NCI‐PDQ and AUA Guidelines do not recommend endocrine therapy for treating LPC. However, CaPSURE's surveillance( 5 ) shows that the proportion of PADT use rose sharply between 1989 and 2001, from 4.6% to 14.2%, from 8.9% to 19.7%, and 32.8% to 48.2% in low, intermediate and high risk groups, respectively. By way of reference, WW cases dropped significantly during the same period. These phenomena may be attributable to a critical report pointing out that watchful waiting (WW) merely awaits the progression of symptoms( 16 ) and to the influence of the development of LH‐RH agonists and anti‐androgenic agents. Furthermore, publication of data in recent years showing life‐prolonging effects of neoadjuvant ADT (premised on radiation therapy) as well as of post‐radical prostatectomy adjuvant ADT many have had a large impact.( 17 , 18 ) The life‐prolonging effects of adjuvant and neoadjuvant ADT for these high‐risk LPC and LAPC patients have continued to be reported since then.( 19 , 20 , 21 ) However, these reports do not prove a life‐prolonging effect of PADT. As the authors concluded in their report,( 5 ) future clinical trials must define more clearly the appropriate role of hormone therapy in LPC, and their results should be updated in practical guidelines.

Clinical trials of primary androgen depletion therapy performed for localized prostate cancer or locally advanced prostate cancer

Evidence from Japan

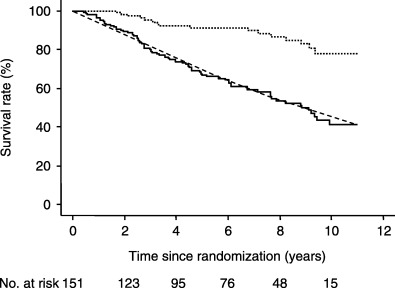

PADT has thus far been performed extensively in Japan for all morbidity phases of prostate cancer. According to a report published in 1988 by the Ministry of Health and Welfare's Prostate Cancer Group Conference,( 22 ) the age of onset of the 565 patient cases that had been compiled peaked between 70 and 79 years. By morbidity phase, A1 was 6.2%, A2 was 3.7%, B was 14.9%, C was 20.7%, D1 was 7.4%, and D2 was 43.7%. As treatment, most patients were given estrogen, with about half undergoing surgical castration concurrently. The measured 5‐year survival rate by morbidity phase was 89.2% for A1, 66.1% for A2, 72.7% for B, 51% for C, 47.5% for D1 and 28% for D2. Notable in this report are: (i) that about half the patients suffered metastatic cancer, confirming that a rapid stage migration had occurred during this period, as the above‐mentioned JUA compilation of 2000( 4 ) stated that only 8% of patients had metastasis; (ii) even before LH‐RH agonists and non‐steroidal anti‐androgen agents were introduced, many patients underwent a combination of surgical castration and administration of estrogen preparations, the so‐called first‐generation MAB therapy; and (iii) there was a relatively high 5‐year survival rate. Later, two multicenter prospective randomized comparative trials (study 1 and study 2) were carried out in Japan, beginning in 1991, to investigate the efficacy of ADT against either LPC or LAPC. To date, the results of up to 5 years follow‐up have been released.( 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ) Study 1 investigated neoadjuvant as well as adjuvant hormone therapies in patients who underwent radical prostatectomy, while study 2 investigated the efficacy of PADT in patients who did not undergo radical prostatectomy for one reason or another. Allocation to radical prostatectomy was not randomized as the two studies were designed independently, and in the early stages after the start of the studies, no interstudy comparisons were planned. However, in analyzing the 5‐year follow‐up data, it was believed that because both studies were implemented at the same time at the same medical institutions, comparing the results of studies 1 and 2 would provide information on the efficacy of PADT against early stage prostate cancer (for which no substantial evidence has yet been obtained). Therefore, the interstudy survival rate was compared retrospectively.( 27 ) Both study 1 and study 2 had a 5‐year cause‐specific survival rate of approximately 90%, and the 5‐year overall survival rate was shown to be almost at the same level as the expected survival rate in both groups. This suggests that PADT provided a similar level of therapeutic effect to that obtained from radical prostatectomy. These studies continue to be followed up. Fig. 3 shows the results of study 1, that is, the results following up to 10 years of PADT (date from the study office). At this time point, the overall survival rate is the same as the expected survival rate of same‐generation individuals. It is worth noting that about 40% of the patients enrolled in this study were in stage C of the disease.

Figure 3.

Ten‐year prognosis of primary androgen depletion therapy (PADT) performed in patients who did not undergo radical prostatectomy for one reason or another. A characteristic feature is that the expected survival curve of same‐generation individuals perfectly matches the test patients’ overall survival curve. ( … ) Cause‐specific survival; (‐) overall survival; (‐‐‐) expected survival.

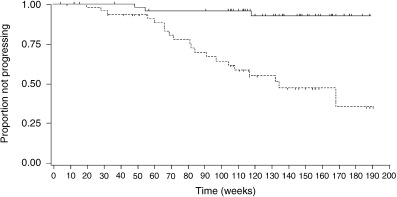

Another interesting clinical study was conducted in Japan.( 29 ) This was a double‐blind trial in stage C and stage D patients, comparing LH‐RH agonist monotherapy with MAB therapy comprising a LH‐RH agonist plus bicalutamide (80 mg/day). The test revealed that MAB therapy was markedly effective, especially for stage C patients.( 30 ) Combination therapy with bicalutamide 80 mg produced significant (P < 0.001) advantages over LHRH‐A alone in terms of time to treatment failure (TTTF; 117.7 weeks versus 60.3 weeks; Hazard ratio (HR) 0.54; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.38, 0.77) and time to progression (TTP; HR 0.40; 95% CI 0.26, 0.63). The differences in TTTF and TTP were greater than those reported at an earlier follow‐up.( 29 ) There was no difference in the interim overall survival between treatment groups (87.3%versus 82.2%; P = 0.365). Withdrawal of bicalutamide 80 mg after disease progression led to a further response in seven of 18 (38.9%) patients. Most patients (31/40, 77.5%) experiencing disease progression on LHRH‐A alone subsequently responded to the addition of bicalutamide 80 mg.

This analysis revealed that the effect of bicalutamide 80 mg therapy on TTP is most pronounced in patients with locally advanced disease (stage C; Fig. 4). The baseline characteristics of the two treatment groups were well balanced among patients with stage C disease. This suggests that, although combination therapy using bicalutamide 80 mg has the potential to benefit all patients with advanced/locally advanced disease, the benefit over castration alone is greatest for patients with locally advanced tumors without distant spread to lymph nodes or elsewhere.

Figure 4.

Time to disease progression among patients with stage C prostate cancer treated with luteinizing hormone‐releasing hormone (LHRH)‐A with and without bicalutamide. P < 0.001. (‐) Bicalutamide 80 mg combination therapy (n = 52; three events [5.8%]); (‐‐‐) LHRH‐A monotherapy (n = 47; 20 events [42.6%]).

Evidence from Europe and the USA

Labrie states that LPC responds best to LH‐RH agonist/pure anti‐androgen combination therapy, with a complete remission achieved in over 90% of patients who undergo treatment for more than 6 and a half years.( 31 ) Labrie emphasizes that, clinically, this MAB therapy has the potential to prevent almost all LPC patients from dying of prostate cancer.( 32 ) Moreover, the current Early Prostate Cancer (EPC) trial is attracting attention. This is a large‐scale, multicenter trial targeting LPC and LAPC patients who are divided into a WW group, a radical prostatectomy group, and an external beam radiation group, and are randomly allocated to receive either a placebo or bicalutamide. In this trial, the effects of ADT and PADT against LPC and LAPC are beginning to be reported. Reporting on this study, Wirth et al.( 33 ) found that, in the overall population, the group receiving bicalutamide saw a significant (28%) improvement in progression‐free survival as compared with the placebo group. However, because no intergroup differences are yet to be seen in terms of overall survival at the 5.4‐year time point (the median follow‐up period), we await further results.

Conclusion

Sharifi et al.( 34 ) analyzed the English‐language literature on ADT released from 1966 to March 2005 and summarized this as follows: ADT has a clear role in the management of advanced prostate cancer and high‐risk localized disease. The benefits of ADT in other settings need to be weighed carefully against substantial risks and adverse effects on quality of life.

In this review, I have focused on PADT for LPC and LAPC patients. The reasons are that, even after the introduction of radical prostatectomy via an anatomical approach into Japan,( 8 ) there are still many patients who undergo PADT, and also that the USA is seeing a gradual increase in the number of patients who are treated by PADT. In considering the validity of this trend, it is important to understand the natural history of LPC and LAPC. In this respect, Albertsen et al.'s( 14 ) report of a 20‐year follow‐up observational study is extremely important. This report can be interpreted as revealing the natural history of PADT. This is because over 40% of the patients had undergone endocrine therapy within 6 months of being diagnosed with the disease. While WW is a strategy that merely awaits the progression of symptoms, as I have discussed, PADT is fully eligible to be considered as one of the treatment options for LPC and LAPC. One future challenge is finding ways to truly eliminate ‘insignificant cancer’. This is exactly the same challenge faced by other treatment methods, such as surgery and radiation therapy. However, if the aggressiveness of treatment is taken into consideration, PADT can eliminate ‘insignificant cancer’ with fewer unwanted effects than other therapies. Of course, there still remains the problem of adverse reactions caused by ADT. Reduction in libido and potency attributable to LH‐RH agonists and reduction in bone mineral content can be resolved to a certain extent by replacing them with pure anti‐androgen agents. Gynecomastia, which is an adverse reaction caused by pure anti‐androgen agents, can be overcome by administration of tamoxifen.( 35 ) There is a good possibility of a new molecular‐target drug aimed at androgen receptor blockade being developed.( 36 ) Circumstances such as this make me confident that therapeutic strategies for LPC and LAPC are likely to change dramatically in the near future.

References

- 1. AUA. AUA Guidelines. Available from URL: http://www.auanet.org/guidelines/.

- 2. NCI‐PDQ. Available from URL: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/prostate/healthprofessional/.

- 3. Aus G, Abbou CC, Pacik D et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2001; 40: 97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cancer Registration Committee of Japanese Urological Association. Clinicopathological statistics on registered prostate cancer patients in Japan: 2000 report from the Japanese Urological Association. Int J Urol 2005; 12: 46–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cooperberg MR, Grossfeld GD, Lubeck DP, Carroll PR. National practice patterns and time trends in androgen ablation for localized prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003; 95: 981–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Huggins C, Stephens RC, Hodges CV. Studies on prostate cancer: 2. The effects of castration on advanced carcinoma of the prostate gland. Arch Surg 1941; 43: 209. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang MC, Valenzuela LA, Murphy GP, Chu TM. Purification of a human prostate specific antigen. Invest Urol 1979; 17: 159–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Walsh PC, Lepor H, Eggleston JC. Radical prostatectomy with preservation of sexual function: anatomical and pathological considerations. Prostate 1983; 4: 473–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Okihara K, Nakanishi H, Nakamura T et al. Clinical characteristics of prostate cancer in Japanese men in the eras before and after serum prostate‐specific antigen testing. Int J Urol 2005; 12: 662–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Takayasu H, Ogawa A, Koiso K et al. Results of the treatment of prostate cancer. Nippon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi 1978; 69: 426–35. (In Japanese). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maruoka M, Ando K, Nozomi K et al. Endocrine therapy for prostate cancer. Nippon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi 1982; 73: 432–7. (In Japanese). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kumamoto E, Tsukamoto T, Umehara T et al. Clinical studies on endocrine therapy of prostatic carcinoma (1): Multivariate analyses of prognostic factors in patients with prostatic carcinoma given endocrine therapy. Hinyokika Kiyo 1990; 36: 275–84. (In Japanese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Veterans Administration Cooperative Urological Research Group. Treatment and survival of patients with cancer of the prostate. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1967; 124: 1011–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Albertsen PC, Hankey JA, Fine J. 20‐year outcome following conservative management of clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA 2005; 293: 2095–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Akaza H, Usami M, Hinotsu S et al. Characteristics of patients with prostate cancer who have initially been treated by hormone therapy in Japan: J‐CaP surveillance. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2004; 34: 329–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McLaren DB, MaKenzie M, Duncan G, Pickies T. Watchful waiting or watchful progression? Prostate specific antigen doubling times and clinical behavior in patients with early untreated prostate carcinoma. Cancer 1998; 82: 342–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bolla M, Gonzalez D, Warde P et al. Improved survival in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy and goserelin. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Messing EM, Manola J, Sarosdy M et al. Immediate hormone therapy compared with observation after radical prostatectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy in men with node positive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 1781–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bolla M, Collette L, Bank L et al. Long‐term results with immediate androgen suppression and external irradiation in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer (an EORTC study): a phase III randomized trial. Lancet 2002; 360: 103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Messing E, Manola J, Sarosdy M et al. Immediate hormone therapy compared with observation after radical prostatectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy in men with node‐positive prostate cancer: results at 10 year of EST 3886. J Urol 2003; 169: 1480. 12629396 [Google Scholar]

- 21. D’Amico AV, Manola J, Loffredo M et al. 6‐month androgen suppression plus radiation therapy vs radiation therapy alone for patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA 2004; 292: 821–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Akakura K, Isaka S, Fuse H et al. Trends in patterns of care for prostatic cancer in Japan: statistics of 9 institutions for 5 years. Hinyokika Kiyo 1988; 34: 123–9. (In Japanese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Homma Y, Akaza H, Okada K et al. Prostate Cancer Study Group. Preoperative endocrine therapy for clinical stage A2, B, and C prostate cancer: an interim report on short‐term effects. Int J Urol 1997; 4: 144–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Homma Y, Akaza H, Okada K et al. The Prostate Cancer Study Group. Early results of radical prostatectomy and adjuvant endocrine therapy for prostate cancer with or without preoperative androgen deprivation. Int J Urol 1999; 6: 229–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Akaza H, Homma Y, Okada K et al. The Prostate Cancer Study Group. Early results of LH‐RH agonist treatment with or without chlormadinone acetate for hormone therapy of naive localized or locally advanced prostate cancer: a prospective and randomized study. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2000; 30: 131–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Akaza H, Homma Y, Okada K et al. Prostate Cancer Study Group. A prospective and randomized study of primary hormonal therapy for patients with localized or locally advanced prostate cancer unsuitable for radical prostatectomy: results of the 5‐year follow‐up. BJU Int 2003; 91: 33–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Homma Y, Akaza H, Okada K et al. Prostate Cancer Study Group. Endocrine therapy with or without radical prostatectomy for T1b‐T3N0M0 prostate cancer. Int J Urol 2004; 11: 218–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Homma Y, Akaza H, Okada K et al. Prostate Cancer Study Group. Radical prostatectomy and adjuvant endocrine therapy for prostate cancer with or without preoperative androgen deprivation: Five‐year results. Int J Urol 2004; 11: 295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Akaza H, Yamaguchi A, Matsuda T et al. Superior anti‐tumor efficacy of bicalutamide 80 mg in combination with a luteinizing hormone‐releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist versus LHRH agonist monotherapy as first‐line treatment for advanced prostate cancer: interim results of a randomized study in Japanese patients. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2004; 34: 20–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Akaza H, Yoshida H, Takimoto S et al. Bicultamide 80 mg in combination with an LHRHa versus LHRHa monotherapy in previously untreated advanced prostate cancer: a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial 2005: ASCO abstract.

- 31. Labrie F, Candas B, Gomez JL, Cusan L. Can combined androgen blockade provide long‐term control or possible cure of localized prostate cancer? Urology 2002; 60: 115–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Labrie F, Cusan L, Gomez J et al. Major impact of hormonal therapy in localized prostate cancer – death can already be an exception. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2004; 92: 327–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wirth MP, See WA, McLeod DG et al. Bicalutamide 150 mg in addition to standard care in patients with localized or locally advanced prostate cancer: results from the second analysis of the early prostate cancer program at median followup of 5.4 years. J Urol 2004; 172 (5 Part 1): 1865–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sharif N, Gulley JL, Dahut WL. Androgen depletion therapy for prostate cancer. JAMA 2005; 294: 238–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Boccardo F, Rubagotti A, Bataglia M et al. Evaluation of tamoxifen and anastrozole in the prevention of gynecomastia and breast pain induced by bicalutamide monotherapy of prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 808–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chabner BA, Roberts TG. Chemotherapy and the war on cancer. Nature Rev Cancer 2005; 5: 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]