Abstract

Purpose

Digital amputation is a commonly performed procedure for infection and necrosis in patients with diabetes, peripheral vascular disease (PVD), and on dialysis. There is a lack of data regarding prognosis for revision amputation and mortality following digital amputation in these patients.

Methods

All digital amputations over 10-year period (2008–2018) at a single center were reviewed. There were 484 amputations in 360 patients, among which 358 were performed for trauma (reference sample) and 126 for infection or necrosis (sample of interest). Patient death and revision were determined from National Vital Statistics System and medical records. Propensity score matching was performed to compare groups. Data were then compared to the Social Security Administration Actuarial Life Table for 2015 to determine age-matched expected mortality.

Results

The 2-year revision rate was 34% for amputations performed for infection or necrosis, compared to 15% for amputations due to trauma. For amputations performed for infection or necrosis, the revision rate was 47.7% when diabetes, PVD, and dialysis were present. Among all patients with infection or necrosis (n = 104) undergoing a digital amputation, overall survival at 2, 5, and 10 years was 79.4%, 57.3%, and 17.5%, respectively, which represented a 3.2-fold increased risk of death compared to controls. (hazard ratio, 3.19; 95% confidence interval, 1.47–6.93). For amputations due to trauma, mortality was no different from that in the age-matched general population.

Conclusions

Mortality and revision risk are high for patients requiring a digital amputation for infection or necrosis and are further increased with medical comorbidities. Hand surgeons should consider the prognostic implications of these data when counseling patients.

Type of study/level of evidence

Prognostic IV.

Keywords: Amputation, diabetes, mortality, peripheral vascular disease, revision amputation

Digital amputation is a commonly performed procedure in patients with diabetes, peripheral vascular disease (PVD), and those on dialysis. Often, little consideration is given to counseling patients on the likelihood of revision or overall mortality from their systemic disease. Although it is well-known to hand surgeons that these patients often have complications, the rates of revision and mortality have not been previously quantified. Upper-extremity digital infection or necrosis is thought to be a late finding in diabetes, PVD, and patients on dialysis, and is a harbinger of terminal disease. Although factors influencing revision after traumatic amputation have been well-described,1 there is a paucity of data on revision or mortality following digital amputation for non-traumatic reasons. It has been well-documented that patients with PVD and those undergoing hemodialysis exhibit poor recovery from other surgical procedures with a high likelihood of complications.2 In a study of 20 patients, Stone et al3 found that the 5-year survival for patients on dialysis who had undergone an upper-extremity amputation was 35%. Landry et al4 also reported that dependence on dialysis was associated with decreased survival in patients with finger amputations and that 21% of the patients with PVD needed revision of amputations. Although these studies examined the rates of revision and mortality for patients with PVD, no comparison was made to a reference or general population. Regarding the likelihood of revision, it has been demonstrated that partial amputations of the lower extremities often result in more proximal amputation.5–7 Studies on the upper extremity have reported revision digital amputation rates of 15.1% in traumatic cases1 and 21.1% among patients on hemodialysis,8 with PVD being the most important predictor of the failure of primary healing.

With an infected or necrotic digit, surgeons need accurate data to counsel patients on the likelihood of complications, the need for revision, and the overall prognosis, and against that backdrop, make surgical decisions such as amputation level. National- and institution-level quality assurance programs need the documentation of expected outcomes so that care can be appropriately measured. Thus, our study aimed to document the rates of mortality and revision following digital amputation performed for infection or necrosis with a focus on the influence of diabetes, PVD, and dependence on dialysis, compare the rates of revision to those of amputations performed for trauma as a reference sample, and compare the rates of mortality to those in an age-matched general population. We hypothesized that patients presenting with digital ischemia or necrosis would exhibit increased rates of revision amputation and higher mortality rates and that diabetes, PVD, and dependence on dialysis would be independent predictors of outcome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All primary or revision amputations performed over 10-year period (2008–2018) by 1 of 7 board-certified hand surgeons at our level 1 trauma center were reviewed for any indications or patient factors. The inclusion criteria were adult patients aged at least 18 years requiring any digital amputation procedure. The exclusion criteria were patients with an initial procedure performed by a surgeon without specialized hand training, patients who had an index procedure within 2 years before the initiation of our study, and patients whose index procedure was a ray amputation. A retrospective chart review was performed and demographic data were collected and analyzed. Demographic and clinical data included age, sex, race, ethnicity, smoking status, diabetes, PVD diagnosis, presence and laterality of upper-extremity dialysis access including AV fistulas and tunneled catheters, and primary indication for the procedure as documented by the operating surgeon. We identified amputations by digit and level to accurately track revision procedures separately from additional primary amputations. Multiple revision surgeries on the same digit were tracked as additional procedures and only revision procedures requiring additional shortening of the affected digit were included. To accurately determine mortality, all patients were queried in the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) to determine the date of death. The output from the NVSS was manually cross-checked with our database to ensure accurate results. The study period did not include the year 2019 because the NVSS did not have complete death data for that year when this study was performed. This research was conducted with institutional review board approval.

The 2 primary outcomes of interest in this study were time-to-death and time-to-revision. Time-to-death was analyzed at the patient level and defined as the number of years from the first primary amputation to death. Date of last follow-up was recorded for patients who were alive at the end of the study period. Time-to-revision was analyzed at the amputation level and was defined as the number of years from primary amputation to revision. The date of the last follow-up was used for amputations not requiring revision. The study sample for the time-to-death outcome excluded one patient because of inability to verify the date of death; thus, all analyses at the patient level represented 360 patients. The study sample for the time-to-revision outcome excluded 23 ray amputations among 13 patients; thus, all analyses at the patient level represented 484 amputations among 358 patients.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics including demographics and comorbidities were described using means, SD, frequencies, and percentages. Time-to-death was estimated in the overall sample based on the reason for amputation (infection or necrosis, trauma) using Kaplan-Meier (KM) methodology, with comparisons accomplished using log-rank statistics. To account for multiple amputations in a single patient, time-to-revision was estimated in the overall sample based on the reason for amputation using KM methods, with comparisons achieved using univariate shared frailty models including a cluster-specific random effect to account for within-patient correlation. Additional shared frailty models were performed to examine the effects of multiple comorbidities (dialysis, diabetes, and PVD) on the time-to-revision at the amputation level.

Because of imbalances in demographics and comorbidities between patients with infection or necrosis and trauma amputation in this sample, a 1–1 nearest neighbor propensity score matching method with replacement was implemented to reduce bias. Several steps were taken to match infection or necrosis and trauma amputation patients on a propensity score. First, a logistic regression model was used to estimate the propensity score using demographics and comorbidities, including age, sex, race, ethnicity, smoking status, diabetes, PVD, and dialysis. Then, the propensity scores from the logistic regression model were used to match each infection or necrosis amputation patient with a trauma amputation patient. Absolute standardized differences (ASMDs) were used as a balance statistic for individual matching variables, where an ASMD value below 0.20 is desirable for all variables.9 Lastly, matched data were extracted and used to compare the time-to-death between the amputation groups and the general population using weighted KM curves. Survival estimates for the general population were produced using the method of Finkelstein et al10 and the Actuarial Life Table for 2015 was used from the Social Security Administration.11 Propensity score and matching procedures were conducted using the “Match It” package in the statistical software R version 4.0.0. Statistical significance was considered at the P < .05 level.

RESULTS

Demographics

There were 484 amputations among 360 patients who met the inclusion criteria, with 358 amputations among patients who experienced trauma (n = 256) and 126 among patients with infection or necrosis (n = 104). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Patients were mostly men (80.3%), White (89.4%), not Hispanic or Latino (95.0%), active smokers (55.6%), and had a mean age of 50.3 years (SD, 17.5 years) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics (n = 360)

| Reason for Amputation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Overall Sample (n = 360) | Infection or Necrosis (n = 104) | Trauma (n = 256) |

|

| |||

| Age at first primary amputation (y) | |||

| mean ± SD | 50.28 ± 17.45 | 56.91 ± 15.41 | 47.71 ± 17.61 |

| median (Q1, Q3) | 51.50 (37.50, 63) | 58 (48, 67.50) | 48 (33, 61) |

| (min, max) | (18, 90) | (21, 86) | (18, 90) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 71 (19.7%) | 35 (33.7%) | 36 (14.1%) |

| Male | 289 (80.3%) | 69 (66.3%) | 220 (85.9%) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 322 (89.4%) | 89 (85.6%) | 233 (91.0%) |

| Black or African American | 26 (7.2%) | 12 (11.5%) | 14 (5.5%) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 3 (0.8%) | 1 (1.0%) | 2 (0.8%) |

| Missing | 9 (2.5%) | 2 (1.9%) | 7 (2.7%) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 9 (2.5%) | 2 (1.9%) | 7 (2.7%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 342 (95.0%) | 99 (95.2%) | 243 (94.9%) |

| Not documented | 5 (1.4%) | 1 (1.0%) | 4 (1.6%) |

| Missing | 4 (1.1%) | 2 (1.9%) | 2 (0.8%) |

| Active smoking status, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 200 (55.6%) | 65 (62.5%) | 135 (52.7%) |

| No | 160 (44.4%) | 39 (37.5%) | 121 (47.3%) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 110 (30.6%) | 58 (55.8%) | 52 (20.3%) |

| No | 250 (69.4%) | 46 (44.2%) | 204 (79.7%) |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 64 (17.8%) | 47 (45.2%) | 17 (6.6%) |

| No | 296 (82.2%) | 57 (54.8%) | 239 (93.4%) |

| Dialysis, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 35 (9.7%) | 28 (26.9%) | 7 (2.7%) |

| No | 325 (90.3%) | 76 (73.1%) | 249 (97.3%) |

| Number of primary amputations | |||

| mean ± SD | 1.41 ± 0.93 | 1.54 ± 1.26 | 1.35 ± 0.75 |

| median (Q1, Q3) | 1 (1, 1) | 1 (1, 1) | 1 (1, 1) |

| (min, max) | (1, 7) | (1, 7) | (1, 5) |

| Had more than one primary amputation, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 80 (22.2%) | 22 (21.2%) | 58 (22.7%) |

| No | 280 (77.8%) | 82 (78.8%) | 198 (77.3%) |

| Deceased, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 54 (15.0%) | 40 (38.5%) | 14 (5.5%) |

| No | 306 (85.0%) | 64 (61.5%) | 242 (94.5%) |

| Time-to-death (years) | |||

| mean ± SD | 3.50 ± 2.81 | 3.60 ± 2.79 | 3.47 ± 2.83 |

| median (Q1, Q3) | 2.99 (0.97, 5.35) | 2.92 (1.16, 5.19) | 3.03 (0.88, 5.36) |

| (min, max) | (0, 10.41) | (0.04, 10.27) | (0, 10.41) |

| Had at least one revision, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 47 (13.1%) | 19 (18.3%) | 28 (10.9%) |

| No | 313 (86.9%) | 85 (81.7%) | 228 (89.1%) |

Mortality

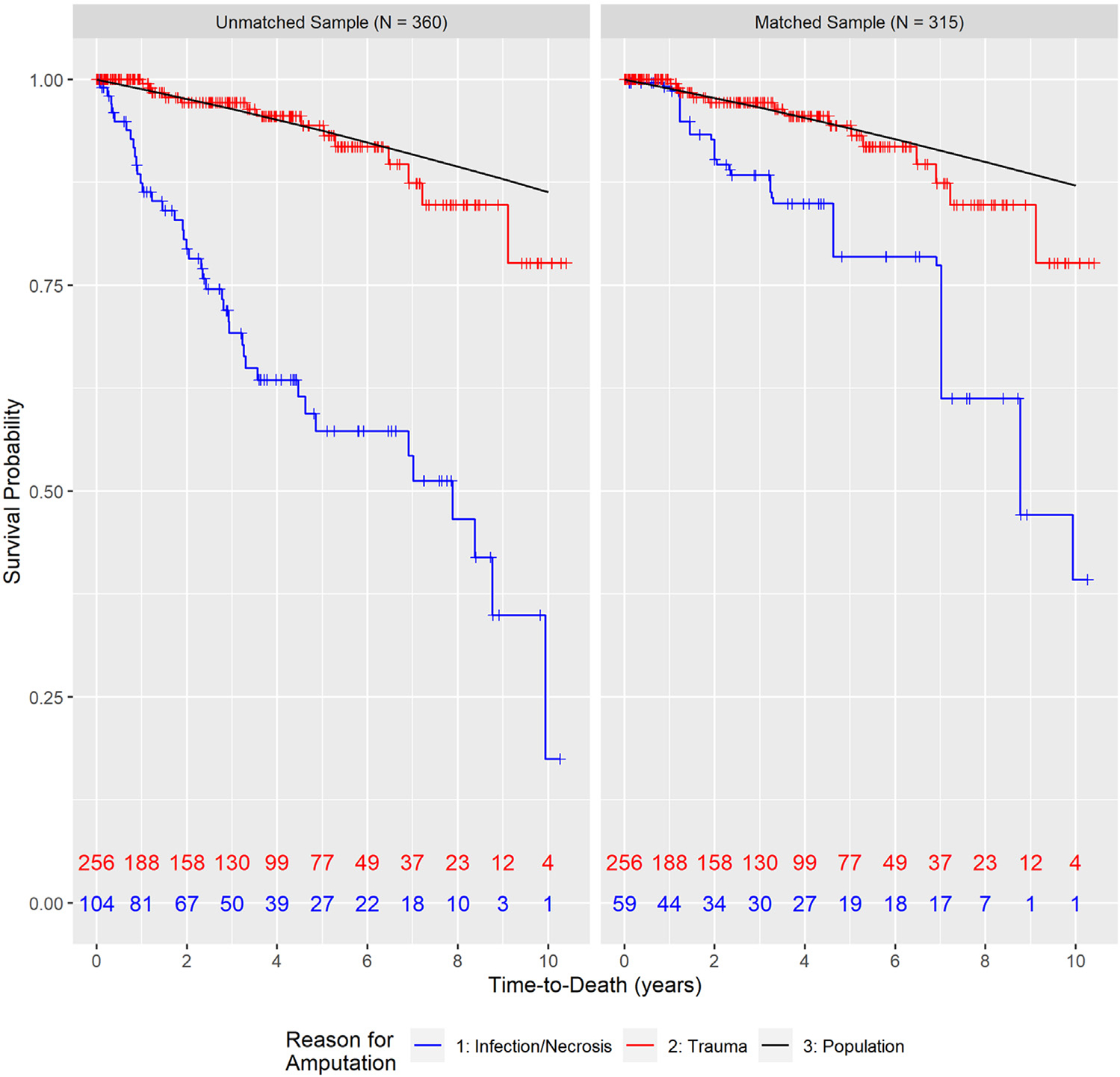

Higher mortality was observed among patients with infection or necrosis (Table 2). There were no significant differences between the trauma group and the age-matched general population (log-rank P = .2106) (Fig. 1).

TABLE 2.

Mortality Distribution for Both Cohorts and All Patients At 2, 5, and 10 Years

| Patient Cohorts | 2-Year Survival Rate | 5-Year Survival Rate | 10-Year Survival Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| All patients | 91.8% | 81.7% | 50.6% |

| Infection or necrosis | 79.4% | 57.3% | 17.5% |

| Patients who experienced trauma | 97.2% | 94.4% | 77.7% |

FIGURE 1:

Kaplan-Meier curves for time-to-death in the unmatched and matched samples.

Significantly lower survival rates among all patients were observed for those with diabetes, PVD, on dialysis, and who had an amputation for infection or necrosis (all log-rank P < .05). No significant differences were observed for active smoking status (log-rank P = .9022) for all patients. In the infection or necrosis group, significant differences in time-to-death were observed among patients with diabetes or on dialysis (both log-rank P < .05). Significant differences in time-to-death were observed among trauma patients with PVD or on dialysis (both log-rank P < .05).

To account for imbalances in demographics and comorbidities between the amputation groups, 1–1 nearest neighbor matching with replacement analysis was performed and our total sample size was narrowed from 360 to a matched sample of 315 patients (59 with infection or necrosis; 256 with trauma). Each patient was matched up to 5 times and all matching variables had ASMD values below 0.20 after matching (Appendix A, available online on the Journal’s website at www.jhandsurg.org). The weighted KM curves and shared frailty models after matching continued to demonstrate significant differences in survival profiles between the groups (P < .05), with patients with infection or necrosis having a 3.2-fold higher risk of death than the trauma amputation patients (control) (Hazard ratio [HR], 3.19; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.47–6.93; P < .05).

Revision amputation

All revisions occurred within 3.3 years, most of which occurred in the first 2 years after the primary amputation. Table 3 displays the results from unmatched, univariate, shared frailty models for time-to-revision regressed on each individual’s comorbidity. These results demonstrated that patients with diabetes versus no diabetes (HR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.14–4.02), PVD versus no PVD (HR, 2.58; 95% CI, 1.31–5.06), dialysis versus no dialysis (HR, 2.37; 95% CI, 1.06–5.28), and infection or necrosis versus trauma amputations (HR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.14–4.13) showed an at least 2.1-fold increased risk of revision amputation. The overall 2-year revision rate was 15% for trauma and 34% for infection or necrosis. No statistically significant differences were observed for smoking status (HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.58–2.06; P = .78) or primary amputation level (P = .18) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Univariate Cox Proportional Hazards Model Results for Time-to-Revision Regressed on Individual Comorbidities* (484 Amputations Among 360 Patients)

| Patient Comorbidities | Hazard ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Diabetes | 2.14 | 1.14–4.02 | < .05 |

| PVD | 2.58 | 1.31–5.06 | < .05 |

| Dialysis | 2.37 | 1.06–5.28 | < .05 |

| Infection or necrosis | 2.17 | 1.14–4.13 | < .05 |

PVD, peripheral vascular disease.

Reference categories for each model were: no diabetes, no PVD, no dialysis, and trauma amputation.

Effect of multiple comorbidities on revision

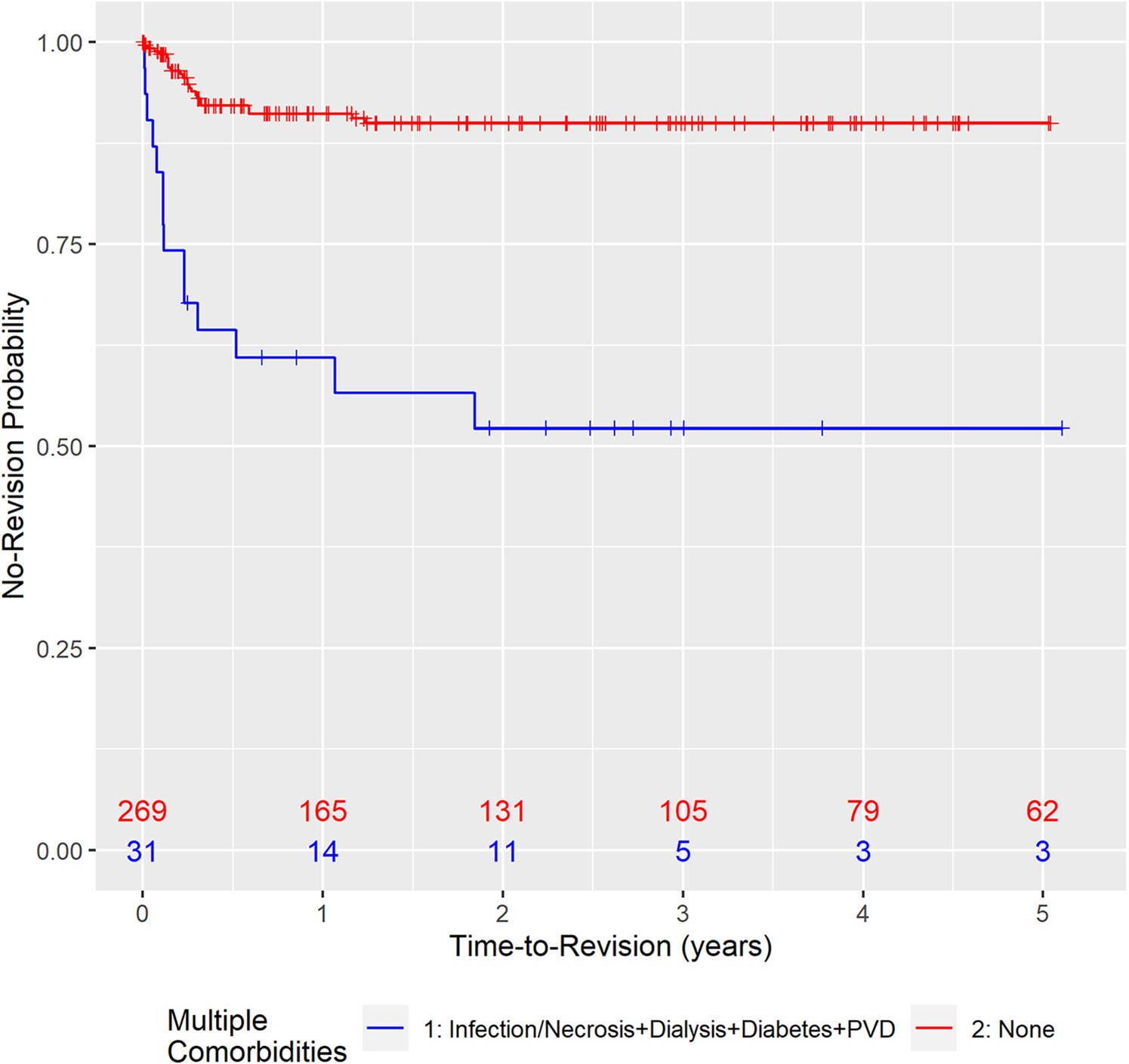

Additional unmatched analyses were performed on patients presenting with infection or necrosis to assess the influence of dialysis, diabetes, and PVD compared to those with no recorded comorbidities. With infection or necrosis, the addition of PVD, dialysis, or diabetes resulted in a significantly increased risk of revision (HR, 8.47; 95% CI, 2.78–25.76; P < .05) compared to patients with no comorbidities, with a 2-year revision rate of 47.7% (Fig. 2, Table 4).

FIGURE 2:

Kaplan-Meier curves for time-to-revision when infection or necrosis, dialysis, diabetes, and PVD are all present versus not present at all (n = 300 amputations among 215 patients). PVD, peripheral vascular disease.

TABLE 4.

Cox Proportional Hazards Model Results for Time-to-Revision Regressed on Multiple Comorbidities*

| Patient Comorbidities | na† | np‡ | Hazard ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Infection or necrosis + dialysis + diabetes + PVD | 300 | 215 | 8.47 | 2.78–25.76 | < .05 |

| Infection or necrosis + dialysis + diabetes | 317 | 223 | 6.16 | 2.10–18.02 | < .05 |

| Infection or necrosis + diabetes + PVD | 324 | 233 | 5.39 | 2.19–13.28 | < .05 |

PVD, peripheral vascular disease.

Reference categories for each model were patients with no recorded comorbidities.

na refers to the number of amputations included in each analysis.

np refers to the number of patients included in each analysis.

DISCUSSION

Mortality and revision following digital amputations for infection and necrosis are common. Although this is well-known to the practicing hand surgeon, precise estimates of revision rates and mortality data are unknown. We aimed to examine the revision rates and mortality data for digital amputations performed for infection or necrosis and compare it to a reference sample, expecting large differences because of amputation and comorbidities. For traumatic amputations, our data confirmed the expected revision rate of 15% as described by others.1 As expected, we did not find any difference in mortality after a traumatic digital amputation compared to an age-matched population. For digital amputations performed for infection or necrosis, we found a revision rate of 34% and as high as 47% when diabetes, PVD, or dialysis was present. Mortality data revealed that when a digital amputation was performed for infection or necrosis, there was a 3.2-fold increased risk of mortality compared to the age-matched population data, which was attributable to the systemic disease that also led to the digital infection or necrosis.

The development of critical digital ischemia in the upper extremity is likely multifactorial, with studies implicating large-vessel proximal stenosis and small-artery occlusive or vasospastic disease.12 The multiple comorbidities often encountered in these patients, including large-vessel vascular disease, diabetes, and end-stage renal disease requiring hemodialysis, either contribute to or are proxy markers of vascular disease leading to digital ischemia. The increased mortality in patients with digital ischemia is presumably more because of the advanced progression of the disease than similar processes in the lower extremity.13 In this study, we demonstrated a 2-year mortality rate of 20% and a 5-year mortality rate of 43% among all patients who underwent a digital amputation because of infection or necrosis. Patients with multiple comorbidities have notably lower survival rates and are more likely to require revision, thus complicating their care. Hand surgeons should be aware that digital infection and necrosis are important harbingers of advanced systemic disease.

The limitations of this study include its retrospective nature and the limited information that could be obtained from the medical records. Nevertheless, complete data were obtained for all analyzed variables and mortality data were verified through the NVSS database. By performing propensity score matching for our experimental sample, we could enhance the quality of our analysis and overcome differences in demographics and comorbidities between groups. Even with propensity score matching, it is possible that there are additional unmeasured or confounding data affecting the results.

Patients with infection or necrosis and multiple medical comorbidities have an exceptionally high revision rate after digital amputation. Considering the risk of failure, it may be reasonable to offer ray amputation as a definitive first-line treatment for digital infection or necrosis in a selected patient population. Ray amputation provides patients with functional use of the hand and little long-term functional disruption.14–16 By proceeding directly to definitive treatment, patients may avoid serial operations and the health care burden associated with prolonged treatment. In practice, the selected level of amputation is highly individualized and requires clinical judgment. This study is not intended to suggest one operation over another but rather to assist surgeons with counseling, establishing expectations, and prognosis. This can improve patient education and quality-of-life decision-making. Lastly, national and institutional quality metrics should consider that digital amputations for infection or necrosis have high rates of revision and mortality, which reflect the expected outcome of the disease.

Supplementary Material

Learning Objectives.

Upon completion of this CME activity, the learner will understand:

Predictors of patient mortality and revision amputation after digit amputation.

The implications of digit amputation for infection/necrosis versus trauma.

Patient comorbidities that influence the chance of revision amputation surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Carilion Clinic Musculoskeletal Research and Education Center and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (award number UL1TR003015) for partly funding this research.

Footnotes

CME INFORMATION AND DISCLOSURES

The Journal of Hand Surgery will contain at least 2 clinically relevant articles selected by the editor to be offered for CME in each issue. For CME credit, the participant must read the articles in print or online and correctly answer all related questions through an online examination. The questions on the test are designed to make the reader think and will occasionally require the reader to go back and scrutinize the article for details.

The JHS CME Activity fee of $15.00 includes the exam questions/answers only and does not include access to the JHS articles referenced.

Statement of Need: This CME activity was developed by the JHS editors as a convenient education tool to help increase or affirm reader’s knowledge. The overall goal of the activity is for participants to evaluate the appropriateness of clinical data and apply it to their practice and the provision of patient care.

Accreditation: The American Society for Surgery of the Hand (ASSH) is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

AMA PRA Credit Designation: The ASSH designates this Journal-Based CME activity for a maximum of 1.00 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

ASSH Disclaimer: The material presented in this CME activity is made available by the ASSH for educational purposes only. This material is not intended to represent the only methods or the best procedures appropriate for the medical situation(s) discussed, but rather it is intended to present an approach, view, statement, or opinion of the authors that may be helpful, or of interest, to other practitioners. Examinees agree to participate in this medical education activity, sponsored by the ASSH, with full knowledge and awareness that they waive any claim they may have against the ASSH for reliance on any information presented. The approval of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is required for procedures and drugs that are considered experimental. Instrumentation systems discussed or reviewed during this educational activity may not yet have received FDA approval.

Provider Information can be found at http://www.assh.org/About-ASSH/Contact-Us.

Technical Requirements for the Online Examination can be found at https://jhandsurg.org/cme/home.

Privacy Policy can be found at http://www.assh.org/About-ASSH/Policies/ASSH-Policies.

ASSH Disclosure Policy: As a provider accredited by the ACCME, the ASSH must ensure balance, independence, objectivity, and scientific rigor in all its activities.

Disclosures for this Article

Editors

Ryan Calfee, MD, MSc, has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Authors

All authors of this journal-based CME activity have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. In the printed or PDF version of this article, author affiliations can be found at the bottom of the first page.

Planners

Ryan Calfee, MD, MSc, has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. The editorial and education staff involved with this journal-based CME activity has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Deadline: Each examination purchased in 2023 must be completed by January 31, 2024, to be eligible for CME. A certificate will be issued upon completion of the activity. Estimated time to complete each JHS CME activity is up to one hour.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harris AP, Goodman AD, Gil JA, Sobel AD, Li NY, Raducha JE, et al. Incidence, timing, and risk factors for secondary revision after primary revision of traumatic digit amputations. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43(11):1040.e1–1040.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stolic R Most important chronic complications of arteriovenous fistulas for hemodialysis. Med Princ Pract. 2013;22(3):220–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stone AV, Xu NM, Patterson RW, Koman LA, Smith BP, Li Z. Five-year mortality for patients with end-stage renal disease who undergo upper extremity amputation. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40(4):666–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landry GJ, McClary A, Liem TK, Mitchell EL, Azarbal AF, Moneta GL. Factors affecting healing and survival after finger amputations in patients with digital artery occlusive disease. Am J Surg. 2013;205(5):566–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kadukammakal J, Yau S, Urbas W. Assessment of partial first-ray resections and their tendency to progress to transmetatarsal amputations: a retrospective study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2012;102(5):412–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borkosky SL, Roukis TS. Incidence of re-amputation following partial first ray amputation associated with diabetes mellitus and peripheral sensory neuropathy: a systematic review. Diabet Foot Ankle. 2012;3:12169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thorud JC, Jupiter DC, Lorenzana J, Nguyen TT, Shibuya N. Reoperation and reamputation after transmetatarsal amputation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2016;55(5):1007–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeager RA, Moneta GL, Edwards JM, Landry GJ, Taylor LM Jr, McConnell DB, et al. Relationship of hemodialysis access to finger gangrene in patients with end-stage renal disease. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36(2):245–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen J Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finkelstein DM, Muzikansky A, Schoenfeld DA. Comparing survival of a sample to that of a standard population. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(19):1434–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Security Social. Actuarial Life Table. Accessed July 19, 2020. https://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4c6.html

- 12.McNamara MF, Takaki HS, Yao JS, Bergan JJ. A systematic approach to severe hand ischemia. Surgery. 1978;83(1):1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lepäntalo M, Fiengo L, Biancari F. Peripheral arterial disease in diabetic patients with renal insufficiency: a review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28(Suppl 1):40–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blazar PE, Garon MT. Ray resections of the fingers: indications, techniques, and outcomes. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(8):476–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peimer CA, Wheeler DR, Barrett A, Goldschmidt PG. Hand function following single ray amputation. J Hand Surg Am. 1999;24(6):1245–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melikyan EY, Beg MS, Woodbridge S, Burke FD. The functional results of ray amputation. Hand Surg. 2003;8(1):47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.