Abstract

The mammalian neocortex comprises an enormous diversity regarding cell types, morphology, and connectivity. In this work, we discover a post-transcriptional mechanism of gene expression regulation, protein translation, as a determinant of cortical neuron identity. We find specific upregulation of protein synthesis in the progenitors of later-born neurons and show that translation rates and concomitantly protein half-lives are inherent features of cortical neuron subtypes. In a small molecule screening, we identify Ire1α as a regulator of Satb2 expression and neuronal polarity. In the developing brain, Ire1α regulates global translation rates, coordinates ribosome traffic, and the expression of eIF4A1. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the Satb2 mRNA translation requires eIF4A1 helicase activity towards its 5’-untranslated region. Altogether, we show that cortical neuron diversity is generated by mechanisms operating beyond gene transcription, with Ire1α-safeguarded proteostasis serving as an essential regulator of brain development.

Subject terms: Cell fate and cell lineage, Developmental neurogenesis

Here the authors demonstrate how protein translation, controlled by Ire1α, regulates neuronal diversification in the developing neocortex.

Introduction

The molecular origins of cellular diversity in the cerebral cortex have been the center of attention for developmental neuroscientists for decades. Pyramidal glutamatergic neurons of the neocortex are born from the progenitors outlining the ventricular zone (VZ) of the brain primordium and polarize synchronously with their migration to laminate distinct six cortical layers1–6.

Classically, pyramidal cortical neuron subtypes are determined by combinatorial expression of transcription factors (TFs). Among other TFs, earlier-born deep layer neurons express FEZ Family Zinc Finger (Fezf) and COUP-TF-Interacting Protein 2 (CTIP2, also known as Bcl11b), whereby loss of either gene disrupts the corticospinal tract7–11. Special AT-Rich Sequence-Binding Protein 2 (Satb2) is expressed in neurons of all layers and is indispensable for the formation of the corpus callosum12,13. In the murine brain, Satb2-expressing cells are born during a protracted period of development14, including both earlier- and later-born neurons, where Satb2 regulates different transcriptional networks15. The co-expression of Satb2 and other TFs, as well as developmental timing of Satb2 expression determine the cortical connectome and projection neuron fates in the mammalian brain14–16. The temporal progression of ventricular progenitor states requires restriction of multipotency towards generating Satb2-expressing neurons from E14.5 onwards in late cortical lineages17–19. Transcriptional priming in progenitors involves translational repression which restricts expression of early lineage genes in the later-born lineage20. We recently demonstrated such a mechanism for regulating Satb2 with its repressed mRNA in the neuronal precursors as early as the onset of cortical neuron production at E12.5 and showed translation upregulation for chromatin binding TFs, including Satb2, in a critical developmental window during murine mid-gestation21. Translation dynamics in cortical cell subtypes, as well as the translational requirements for key developmental events, such as the temporal succession of cortical progenitor fate, remain unclear.

To date, a plethora of translational regulators and their brain function, particularly regarding the disease context, like neurodegeneration and cancer, have been described. Among them is kinase/RNase Inositol-Requiring Enzyme 1α (Ire1α), also known as endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-to-Nucleus Signaling 1 (Ern1), the main sensor of ER homeostasis and regulator of the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR). Upon ER stress, a translational shift promotes expression of proteins vital for cell survival and restoration of the ER folding capacity22. Additionally, Ire1α regulates stress-independent remodeling of actin filaments by its association with filamin A23, linked to periventricular heterotopia24. Another study unveiled a direct interaction of Ire1α with the translocon machinery in vitro25. Beyond that, homeostatic functions of Ire1α, especially in the developing neocortex, have remained quite elusive.

In this work, we reveal that protein translation regulates the generation of cortical neuron diversity. Using metabolic labeling, we visualize higher translation rates in the progenitors of later-born Satb2-expressing neurons, driving the synthesis of protein translation regulators in later-born cortical lineages. We reveal fundamentally different dynamics of protein synthesis rates during differentiation of early and late progenitor-to-neuron lineages. We find that Ire1α is essential for the development of Satb2-expressing cortical neurons and axon-dendrite polarity. Notably, we show that conditional deletion of Ire1α in the neocortex results in global decrease of translation rates, fewer translation initiation sites, altered ribosome kinetics and decreased expression of initiation factor 4A1 (eIF4A1). Finally, we reveal that Satb2 expression in neurons requires Ire1α-regulated eIF4A1-dependent translational control of 5’UTR of Satb2 itself. Taken together, our study defines post-transcriptional requirements of neuronal progenitors and distinct neuronal subtypes, unveiling the layers of gene expression regulation driving cortical neuron diversity.

Results

Transient attenuation of translation results in loss of Satb2 expression in cortical neurons

The overwhelming majority of research on the sources of cortical cell diversification has employed transcriptomic-based analyses to decode neuronal identities. The central dogma of molecular biology states that the protein, and not the transcriptome, ultimately constitutes the gene output26. Based on our recent discovery21, we hypothesized that protein translation is among the molecular determinants of neuronal subtype identity.

First, we established a mixed primary culture system, in which we separately nucleofected E12.5 and E14.5 cortical cells with dsRed- and EGFP-expressing plasmids, respectively, mixed the now differentially labeled cells, and cultured together to tightly control for the microenvironment. In this nucleofection system, the EGFP-positive late lineage is enriched for Satb2-expressing cells as early as at day-in-vitro one (DIV1) as compared to dsRed-expressing early lineage (Fig. S1a and b, Supplementary Data S1). At DIV1, a similar minor proportion of cells in both early (E12.5) and late (E14.5) progenitor-derived lineages express a mitotic marker Ki67 and Pax6, expressed in radial glia (Fig. S1c). In our mixed culture system at DIV5, dsRed-labeled early lineage enriched for deeper layer marker-expressing neurons and EGFP-expressing later lineage for Satb2 (Fig. S1d and e).

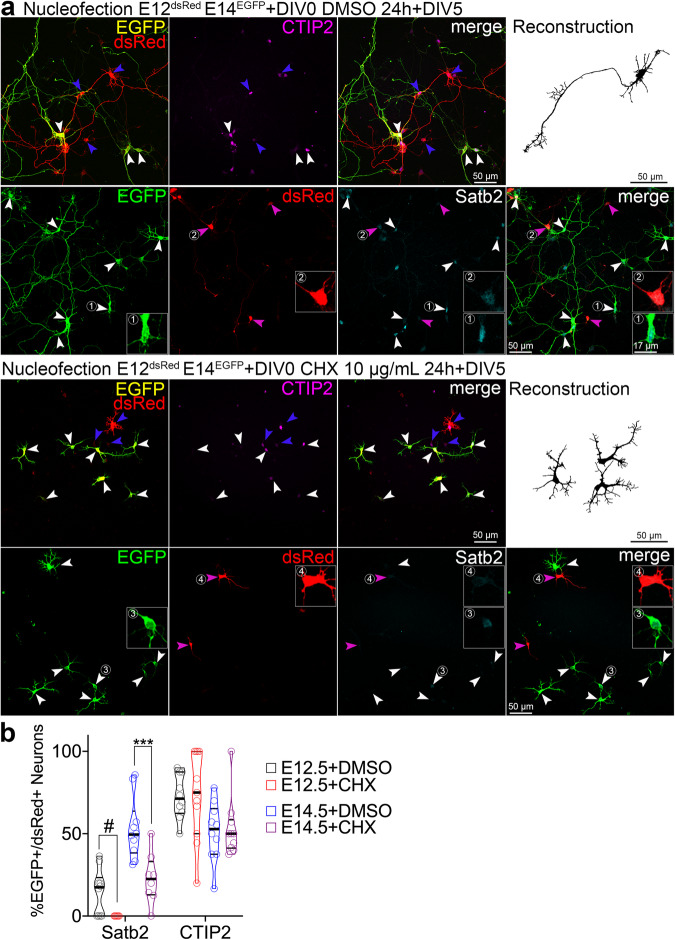

We then asked if pharmacologically attenuating translation early in development alters the type of neurons found in both lineages. We exposed our mixed cultures to either DMSO or cycloheximide (CHX), an inhibitor of protein synthesis27, immediately after plating transiently for 24 h and maintained the cultures until DIV5 in normal medium (Fig. 1a). Remarkably, transient inhibition of translation attenuated Satb2 expression in both lineages but had discernible effect on the expression of CTIP2 (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1. Neuronal Satb2 expression requires a critical window of protein translation in precursor cells.

a Images of immunolabeled primary cells from E12.5 embryos nucleofected to express dsRed, and from E14.5 embryos to express EGFP, mixed and plated on a single glass coverslip. Two hours post-plating, cells were treated with vehicle (DMSO) or cycloheximide (CHX) for 20 hours, followed by medium change, and fixed at day-in-vitro 5 (DIV5). Upper panels show staining using rat anti-CTIP2, goat anti-EGFP, and rabbit anti-RFP, the latter one recognizing both EGFP and dsRed. For this reason, E12.5 cells in this case were recognized as solely expressing dsRed (blue arrowheads), but the E14.5 ones, both EGFP and dsRed (white arrowheads). Lower panels show anti-Satb2, anti-EGFP and anti-dsRed immunostaining with no cross-reacting antibodies; in this case, E12.5-derived cells express dsRed (blue arrowheads) and E14.5 ones EGFP (white arrowheads), as expected. Representative neuronal morphology is demonstrated as a semi-automated, EGFP- or dsRed-based reconstruction. (1-2) Example E14.5 (1,3) or E12.5 (2,4) cortex-derived cells immunolabeled with an antibody anti-Satb2. b Quantification of the cell identity markers in DIV5 neurons derived from E12.5 or E14.5 cortex. Lines on violin plot indicate median and quartiles. For statistics, Satb2, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test; E14.5 + DMSO vs. E14.5 + CHX, p = 0.0007; CTIP2, Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. # indicates a comparison between fractions of Satb2-positive E12.5 DMSO- and E12.5 CHX-treated group, the latter represented by no positive cells. Data were collected from three independent cultures. *** p < 0.001. Refer to Supplementary Data S1 for detailed information on numerical values.

Transient translation inhibition increased the proportion of Ki67-positive, but not of pHH3 positive cells at the end of the treatment at DIV1 (Fig. S1f and g). Nevertheless, control and CHX-exposed cells expressed neuronal NeuN at DIV5, indicating no differentiation defects (Fig. S1h). The inhibition paradigm did not alter the expression of neuronal fate markers Brn2 or Tbr1, signifying a specific requirement of protein translation for Satb2 in developing cortical neurons (Fig. S1i–k).

Additionally, EGFP-expressing neurons of the late lineage projected a Tau-1-positive axon (Fig. S1l), while most treated neurons failed to break their symmetry and expressed Tau-1 in the soma (Fig. S1l). We quantified a CHX-induced loss of axons (Fig. S1m), overall reduction of neurite branching (Fig. S1n and o) and aberrant polarization of KDEL-labeled ER (Fig. S1p and q). Altogether, transiently inhibiting protein synthesis reveals a critical translational window for development of Satb2 expression and neuronal polarization.

The progenitors of later-born neurons exhibit higher translation rates

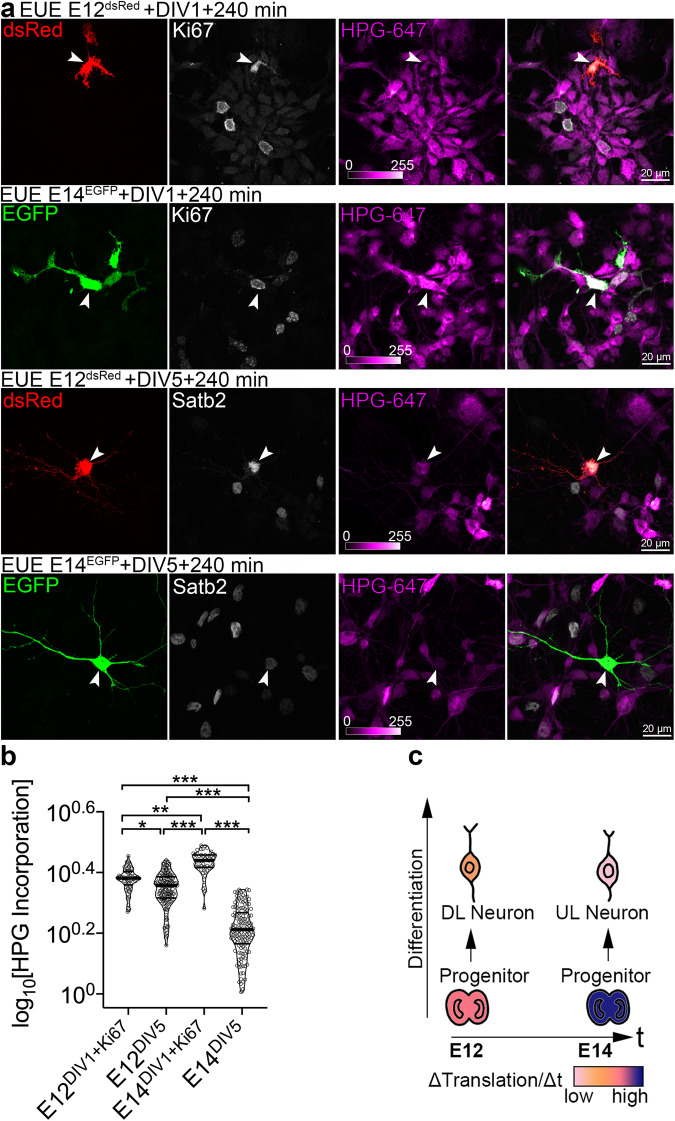

Next, we studied the global translation rates in cycling cortical progenitors, earlier- and later-born neurons using Fluorescent Non-canonical Amino Acid Tagging (FUNCAT)28,29. To label cortical cell lineages, we used ex utero electroporation (EUE), a method of in vivo DNA delivery to a spatiotemporally defined subset of cycling progenitors at the VZ of the embryonic cortex30. We electroporated VZ progenitors at E12.5 with dsRed- and E14.5 progenitors with EGFP-encoding vectors and cultured them in the presence of L-homopropargylglycine (HPG), an alkyne analog of L-methionine. After a Huisgen alkyne-azide cycloaddition reaction, the fluorescence intensity of azide-coupled fluorophore is proportional to incorporation of HPG into newly synthesized proteins and serves as an estimate of translation rate. To ensure cell specificity, we labeled the DIV1 cultures for progenitor-expressed Ki6730,31 and found that E14.5 progenitors displayed higher translation rates as compared to their E12.5 predecessors (Fig. 2a and b). Additionally, we found that such significant upregulation of translation rates in E14.5 progenitors dramatically decreased during their differentiation into postmitotic daughter neurons at DIV5. The early cortical lineages displayed more constant translation rates during neuronal differentiation (Fig. 2c). The majority of E12.5 progenitor-derived DIV5 postmitotic cells co-expressed both Satb2 and CTIP2 in culture, and E14.5 progenitor-derived ones expressed Satb2 and NeuN (Fig. S2a and b).

Fig. 2. Progenitors of later-born neurons display translation rate upregulation.

a Images of primary DIV1 and DIV5 cortical cells immunolabeled for EGFP, dsRed, Ki67, and Satb2. To target Ki67-positive neuronal progenitors and their derived progeny, cortices of E12 embryos were ex utero electroporated (EUE) to express dsRed, and cortices of E14 embryos to express EGFP. Cells were triturated, mixed, plated together on a glass coverslip and pulsed with L-homopropargylglycine (HPG) for 240 min prior to fixation at DIV1 and DIV5. White arrowheads indicate representative cells. b Incorporation of HPG was detected using click reaction with Alexa-647 (HPG-647) and quantified as intensity of fluorescence signal normalized to the cell surface area. c Schematic summarizing the translation rates (ΔTranslation/Δt) in different types of cortical cells from E12- and E14-derived lineage. Deeper layers, DL; upper layers, UL. Violin plots on (b) represent per cell quantifications, thick line median and thin lines quartiles. Quantifications comprise data from three independent cultures. For statistics, D’Agostino-Pearson normality test and Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. Statistical tests were two-sided. For exact p values, please refer to Supplementary Data S1. *** p < 0.001; 0.001 <** p < 0.01; 0.01 <* p < 0.05.

Taken together, the translation rate is a dynamic feature of cortical progenitors and their derived progeny, and likely represents cell- and stage-specific requirements of different protein sets during development.

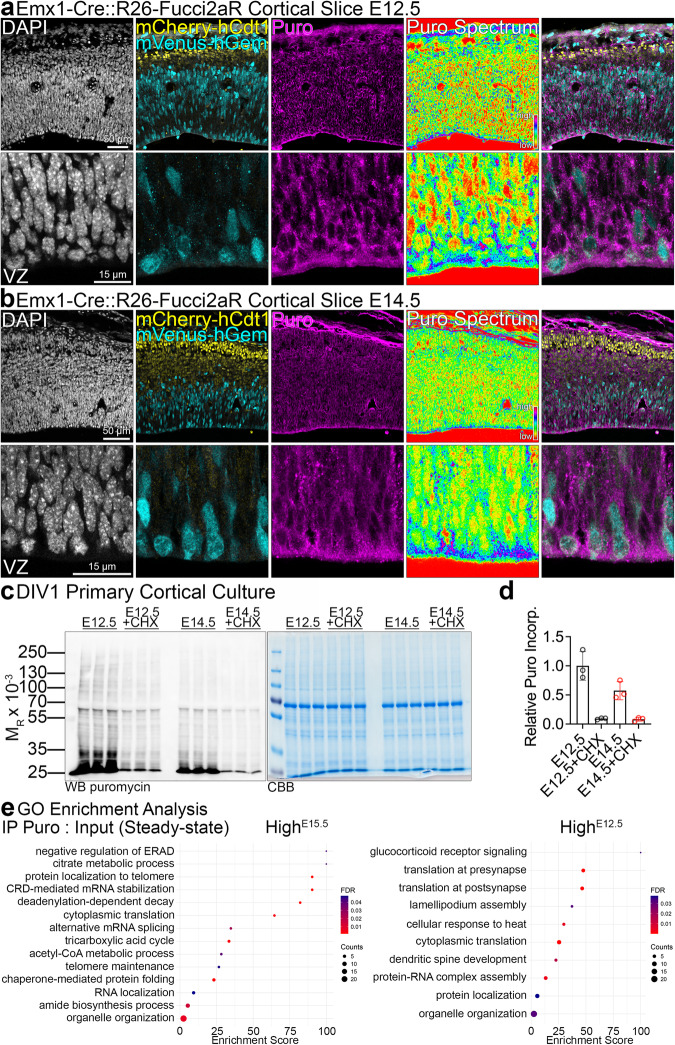

The late cortical lineages upregulate translation of protein synthesis machinery

Because of the dynamic translation rates in the developing cortical lineages, we next investigated their translatome. To label cycling progenitors and postmitotic neurons in vivo, we took advantage of Fucci2aR reporter mouse line. To visualize cortical lineages, we crossed Cre-sensitive Fucci2aR reporter32 to the Emx1Cre/+ driver mouse line, whereby forcing cells of Emx1-lineage in the S/G2/M phases of mitosis to express mVenus. First, we corroborated that ventricular Venus-expressing progenitors are positive for Pax6 (Fig. S2c and d). Next, puromycin labeling of the nascent polypeptides in cortical slices at E12.5 and E14.530,33–35 reinforced our previous findings, demonstrating uniform puromycin labeling throughout the E12.5 cortex as compared to a gradient of puromycin incorporation at E14.5, with its highest level at the VZ (Fig. 3a and b). Next, we prepared cortical primary cultures from bulk E12.5 and E15.5 cortices and pulsed puromycin in the media to label nascent proteins (Fig. 3c and d). Translation inhibition using CHX abrogated puromycin incorporation. We then immunoprecipitated (IPed) puromycilated proteins and subjected the samples to mass spectrometry. We quantified the level of each protein in the IP normalized to its abundance in the input lysate (Supplementary Data S2). Notably, Gene Ontology enrichment analyses for proteins with high IP:input ratio, implicating their higher translation rates, revealed biological pathways specifically represented in early versus late lineages with glucocorticoid receptor signaling, synaptic translation and lamellipodium assembly identified in E12.5 cultures and ER-Associated Degradation, mRNA stability, cytoplasmic translation, and metabolic processes, including tricarboxylic acid cycle in E15.5 cultures (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Data S2).

Fig. 3. The translatome of early and late cortical lineages.

a, b Representative images of anti-puromycin (Puro) immunolabeled slice cultures from E12.5 and E14.5 cortices. Panels labeled Puro Spectrum are intensity encoding renderings of Puro incorporation. Ventricular zone, VZ. The slice culture experiment was repeated three times with similar Puro labeling pattern. c, d Anti-puromycin Western blotting in E12.5 or E14.5 primary cortical cultures at DIV1, pulsed with puromycin and treated with CHX, and Puro incorporation quantification. CBB, Coomassie Brilliant Blue stain to visualize proteins in SDS-PAGE gels. e Summary of GO enrichment analysis based on the normalized abundance of identified proteins in the IP fraction in E15.5 and E12.5 cultures. Refer to Supplementary Data S2 for a full dataset and to Data Availability section for the information on data deposition. Bar graphs show individual data points and averages ± S.D. For statistics on (d), D’Agostino-Pearson normality test and Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test, n = 3 biological replicates per each condition.

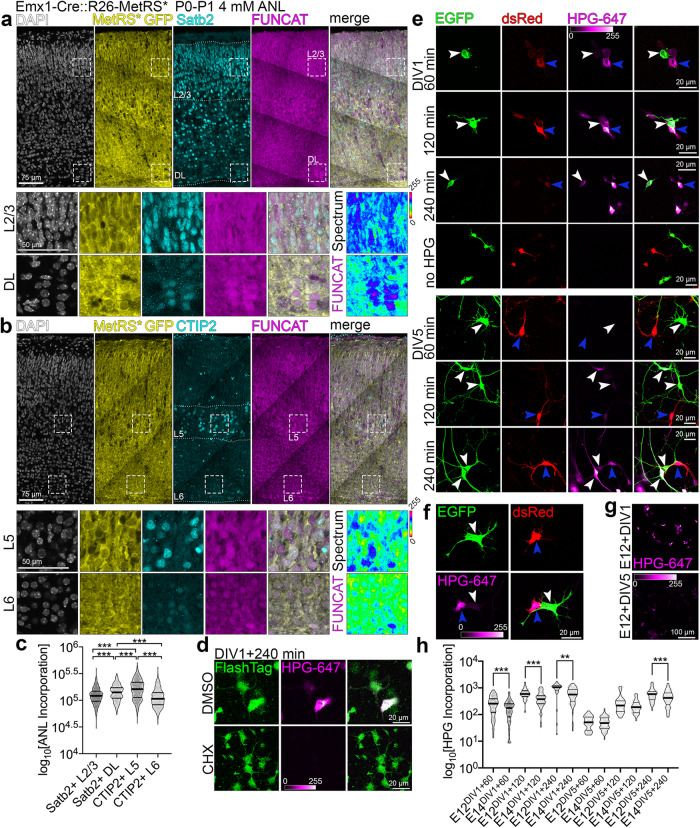

Translation rate is an inherent molecular feature of cortical neuron subtype

We next asked whether differences in translation rates are an intrinsic feature of postmitotic neurons of different cortical layers. We took advantage of MetRS* mouse to study translation rates in cortical neurons in vivo. In this transgenic line, L274G mutation in methionyl-tRNA synthetase allows for a Cre-dependent cell-specific labeling of nascent polypeptide chains using a non-canonical L-methionine analog, amino acid L-azidonorleucine (ANL) and click chemistry36. Induction of the targeting vector is additionally marked by expression of EGFP in cells expressing Cre. To enable metabolic labeling in dorsal telencephalic progenitors and their progeny, we established Emx1-Cre::R26-MetRS* mouse line37 and exposed P0 cortical slices to ANL for 24 hours. Next, we immunostained cortical sections for Satb2 and CTIP2 and “clicked” the ANL to the fluorophore (Fig. 4a and b). This allowed for marker expression- and soma position-based quantification of ANL incorporation in postmitotic neurons within layer 2/3 (L2/3) and deep layers 5 and 6 (DL, L5, L6). We found that translation rate is an inherent molecular signature of cortical neuron subtypes (Fig. 4c), with Satb2-positive DL and CTIP2-positive L5 neurons translating at higher rates in vivo.

Fig. 4. Subtypes of cortical neurons display different protein synthesis rates.

a b Representative images of coronal cortical sections immunolabeled for indicated marker proteins and after click chemistry-based conjugation of ANL and Alexa-647. Squares with dotted outlines represent respective magnified regions. Layer 2/3, L2/3; deep layers, DL. FUNCAT Spectrum represents an intensity encoding rendering of the ANL incorporation signal in each cell, quantified in (c). d DIV1 primary cortical cells from E14 cortex, fed with HPG for 240 min in presence of DMSO or 10 µg/mL cycloheximide (CHX). Note strongly reduced HPG labeling in cells cultured with CHX. FlashTag was added to the medium to label all cells. e Images of primary cortical cells immunolabeled for EGFP (white arrowheads) and dsRed (blue arrowheads), pulsed with HPG for indicated amount of time before fixation at DIV1 and DIV5. HPG was detected with far-red fluorophore-coupled azide. f DIV1 primary cortical cells from e fed with HPG for 240 min. Note significantly higher HPG uptake in E12 cortex-derived immature neurons. g HPG labeling in primary neurons at DIV1 and DIV5 prepared from E12 cortex. Note significantly higher HPG uptake in primary cultures at DIV1. h Incorporation of HPG was quantified as intensity of fluorescence signal normalized to the cell surface in primary neurons. Violin plots on c and h represent data points, thick lines median and thin lines quartiles. Statistics for c and h D’Agostino-Pearson normality test; c one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons; h two-tailed Mann-Whitney tests; for DIV1 60 min and 120 min, p < 0.0001; DIV1 240 min, p = 0.002; DIV5 60 min, p = 0.4888; DIV5 120 min, p = 0.1441; DIV5 240 min, p = 0.0009. For exact p values on c please refer to Supplementary Data S1.*** p < 0.001; 0.001 <** p < 0.01; 0.01 <* p < 0.05.

Given that nucleofection of primary cortical cells selects for postmitotic cells as early as DIV1 (Fig. S1c), we then turned to our mixed culture system. We pulsed HPG in the methionine-free cell culture medium for 60, 120 and 240 minutes at DIV1 (for immature neurons) and at DIV5. The addition of CHX attenuated HPG incorporation, reinforcing the translation-specific nature of our findings (Fig. 4d). At DIV1 following HPG pulse, we quantified significantly higher HPG incorporation rates in neurons derived from E12.5 (dsRed+) versus E14.5 (EGFP+) cortices (Fig. 4e and f). We also detected higher HPG incorporation rates for dsRed-positive neurons at DIV5, with mild differences between the two cell populations. Neurons derived from E14.5 cortex were enriched for Satb2 expression at DIV1 (Fig. S1a and b) and DIV5, whilst E12.5 derived neurons expressed deeper layer markers (Fig. S1d and e). Secondly, we observed, that in both E12.5- and E14.5-derived neuronal cultures, HPG incorporation rates were evidently higher at DIV1 when compared to DIV5 (Fig. 4g), with neurons specified by earlier progenitors translating at higher rates in vitro (Fig. 4h).

Altogether, our findings indicate that cortical neuron subtypes in vivo and in culture can be characterized by protein synthesis efficacy.

Ire1α is a positive regulator of Satb2 in developing cortical neurons

Acute inhibition of translation selectively diminishes Satb2 expression, and a distinct translation rate upregulation takes place in the late progenitors of Satb2-positive neurons (Figs. 1–4). We hypothesized that Satb2 expression is regulated by an upstream signaling modulating protein synthesis.

We have previously developed a method for investigating cell fate acquisition38, which utilizes the Satb2Cre/+ mouse line39. By expressing a Cre-inducible fluorescent reporter loxP-Stop-loxP-tdTomato in E13.5 Satb2Cre/+ primary cortical cells (Fig. 5a), we used cell sorting to quantify the proportion of Satb2-expressing tdTomato-positive cells (Satb2tdTom). Co-transfection with EGFP-encoding plasmid allowed to normalize for the transfection efficiency.

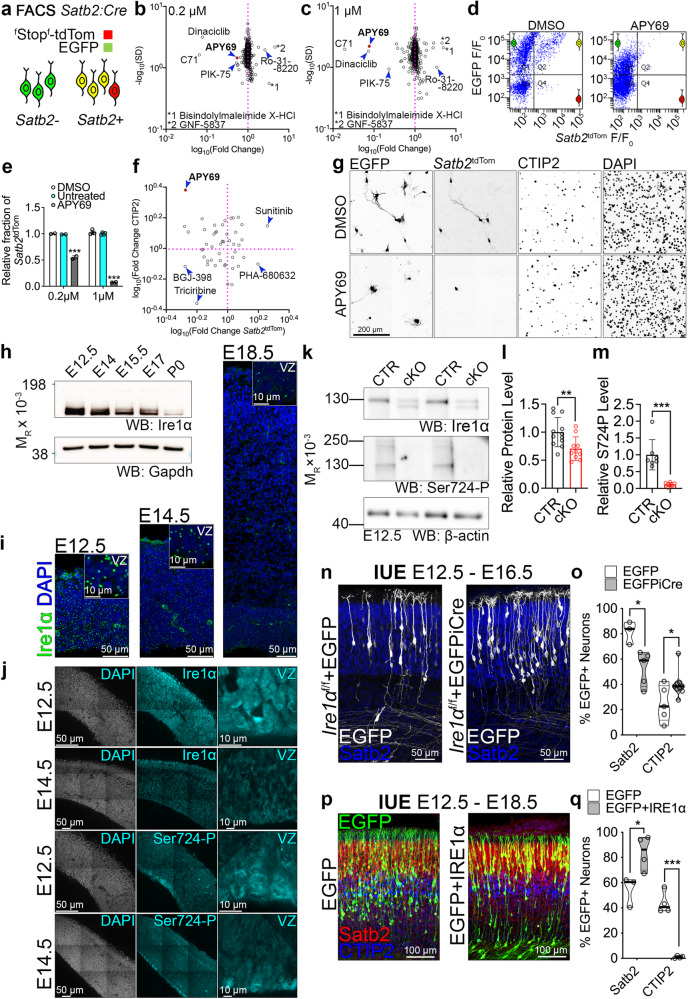

Fig. 5. Small molecule screening reveals Ire1α activity pivotal for Satb2 expression in cortical neurons.

a Screening workflow to identify signaling pathways upstream of Satb2 neuronal identity. b, c The results of the screening using two concentrations of each drug. Each dot represents a tested inhibitor. For full dataset, refer to Supplementary Data S3. Compound 71, C71. d Representative results of flow cytometry of DIV2 neurons treated with DMSO and APY69, a selective inhibitor of Ire1α. e Quantification of the proportion of Satb2-positive neurons. Because of the sheer number of the samples analyzed in the screening, we derived the statistics from two biological replicates per compound per each inhibitor dose. The screening data is further validated on Figs. 5f-5g. f–g Immunohistochemical screening validation. f DIV2 neurons were immunostained for tdTom and CTIP2 and their proportions were quantified. g Representative immunostaining results for DMSO- and APY69-treated cortical neurons. h Western blotting in cortical lysates to profile developmental expression of Ire1α. Gapdh, loading control. i Fluorescence in situ hybridization for Ire1α in cortical sections at indicated developmental stages. Insets demonstrate enlarged fragments of the ventricular zone (VZ). j Representative immunostainings in E12.5 and E14.5 wild-type cortices using indicated antibodies. k Representative results of Western blotting in E12.5 cortical lysates from Ire1αf/f (CTR) or Ire1αf/f; Emx1Cre/+ (cKO) embryos. l,m Quantification of the results from k. n Representative images of immunostaining against EGFP and Satb2 in E16.5 coronal cortical sections of Ire1αf/f embryos after in utero electroporation (IUE) at E12.5 with plasmids encoding for EGFP or EGFP and Cre simultaneously. o Quantification of neuronal cell identity after IUE described in n. p Representative images of cortical coronal sections at E18.5 after IUE in wild-type E12.5 embryos to express EGFP, or EGFP and human IRE1α. q Quantification of neuronal cell identity after IUE described in p. For n and p compare Fig. S13. For h and k compare Fig. S14. Bar graphs show individual data points and averages ± S.D. Thick lines on violin plots represent median, thin lines represent quartiles. Statistics for e one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test; l Mann-Whitney test, ncortices for CTR = 12 and for cKO=10, p = 0.0082; m unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction, ncortices for CTR = 7 and for cKO=7, p = 0.0006; o D’Agostino-Pearson normality test and unpaired t-test, for Satb2 counts, nbrains for EGFP = 3 and for EGFPiCre = 4, p = 0.0185, and for CTIP2 counts, nbrains for EGFP = 5 and for EGFPiCre = 9, p = 0.0372; q D’Agostino-Pearson normality test and unpaired t-test, for Satb2 counts, nbrains for EGFP = 3 and for IRE1α = 4, p = 0.0313, and for CTIP2 counts, nbrains for EGFP = 4 and for IRE1α = 4, p < 0.0001. Statistical tests were two-sided. *** p < 0.001; 0.001 <** p < 0.01; 0.01 <* p < 0.05.

Using this system, we screened a library of small molecule inhibitors for their ability to alter the proportion of Satb2tdTom neurons at DIV240. APY69 was among the strongest modulators of Satb2 expression as tested with increasing compound concentration (Fig. 5b–e, Supplementary Data S3). Validation immunolabeling experiments of inhibitor-treated DIV2 cortical cells for tdTomato and CTIP2 corroborated that APY69 decreased the proportion of Satb2tdTom cells to the benefit of CTIP2-expressing neuron fraction (Fig. 5f and g).

APY69 specifically inhibits Ire1α, an ER-embedded evolutionarily ancient bimodal transmembrane kinase and RNase41,42. Recent evidence highlights an UPR-independent developmental function of Ire1α23. We hypothesized that stress-independent functions of Ire1α might be essential for expression of Satb2.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), Western blotting, and immunolabeling revealed an evident developmental downregulation of Ire1α, expressed homogenously throughout the developing cortex, with its highest levels at E12.5, both at the level of protein, and mRNA (Fig. 5h–j). Notably, we detected robust VZ-enriched immunostaining of S724-phosphorylated Ire1α, one of the critical molecular activity marks of the enzyme43–47. Mice harboring S724A knock-in mutation in Ire1α exhibit markedly reduced Ire1α autophosphorylation and its blunted RNase activity47.

We then went on to validate the pharmacological screening results (Fig. 5a–g) using a knock-out (KO) mouse model. To carve out the role of Ire1α in cortical development, we used the Ire1αf/f line, which enables Cre-dependent deletion of exons 20–21 from the floxed Ire1α allele48. Upon expression of Cre, the kinase-extension nuclease (KEN) domain including RNase active site is disrupted, altering its oligomerization and Ire1α enzymatic activity43,45,49. We conditionally inactivated Ire1α in the progenitors of the dorsal telencephalon by establishing a Ire1αf/f; Emx1Cre/+ mouse line37, Ire1α cKO. Using Western blotting from E12.5 cortical homogenates (Fig. 5k), we confirmed Cre-induced disruption of Ire1α, generation of truncated protein, overall reduction of Ire1α expression (Fig. 5l), and loss of its S724 phosphorylation (Fig. 5m), indicative of the elimination of Ire1α enzymatic activity in the cKO cortex.

To exclude the contribution of the non-Emx1 lineage to our quantification, we prepared murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from Ire1αf/f embryos. We infected cells with control EGFP- and EGFPp2aCre-encoding AAVs (Fig. S3a). At DIV5, the reduction of Ire1α expression in the Cre-infected KO cells was even more evident (Fig. S3b).

Next, we took advantage of in utero electroporation (IUE) to deliver control EGFP or KO-inducing EGFPiCre expression vector30 to multipotent early cortical progenitors at E12.5 of Ire1αf/f embryos able to generate diverse neuronal progeny (Fig. 5n and S3c). Such strategy allows to carve out cell-autonomous role of Ire1α in the development and circumvent possible compensatory mechanisms50. Quantification revealed fewer Satb2-expressing neurons to the benefit of CTIP2-positive ones in the Ire1α KO (Fig. 5o and S3d), without alteration of their laminar positioning within the cortical plate (CP; Fig. S3e and S3f), concordant with our in vitro results (Fig. 5a–g). Silencing of endogenous Ire1α using siRNAs led to a similar neuronal fate switch tendency (Fig. S3g and S3h). Additionally, early progenitor-derived Ire1α KO cortical lineages comprised less Cux1-positive neurons and a tendency towards increased proportion of Sox5-expressing cells, as compared to control lineages (Fig. S3i and j).

Overexpression of human IRE1α in wild-type E12.5 cortical progenitors (Fig. 5p) resulted in an increased proportion of Satb2-expressing neurons at E18.5, and remarkably, hardly any CTIP2-positive neurons (Fig. 5q). Neither the forced expression of spliced Xbp1 (Xbp1S), a cellular stress-associated Ire1α substrate, nor S724 phosphorylation-deficient point mutant of human IRE1α altered the fate of neurons specified by E12.5 electroporated wild-type progenitors (Fig. S3k and S3l).

We also noted disrupted, highly branched morphology of Ire1α KO neurons, compared to majority of bipolar control cells (Fig. S3m and S3n), in both Satb2- and CTIP2- expressing cells (Fig. S3n), localizing across the entire CP (S3o–S3q).

Additionally, post-mitotic promoter NeuroD1-induced expression of Cre in Ire1αf/f at E12.5 and E14.5 did not alter the proportion of Satb2 and CTIP2 neurons four days later, indicative of a neuronal progenitor-embedded role of Ire1α in the acquisition of neuronal identity (Fig. S3r and S3w). We observed an analogous morphological phenotype in NeuroD1-Cre expressing Ire1αf/f neurons as in ones transfected with CAG-EGFPiCre (Fig. S3t and S3w).

Ire1α is required for axon formation in developing cortical neurons of upper layers

In the next experiments, we sought the molecular determinants of the morphological phenotype (Fig. S3m). Given that pyramidal upper layer neurons serve as an established model to study specification of axon-dendrite polarity51, we expressed EGFP or EGFP and iCre in neuronal progenitors of E14.5 Ire1αf/f embryos and fixed the brains at E18.5. In line with previously published results23, loss of Ire1α disrupted laminar positioning of L2/3-destined cortical neurons within the CP (Fig. S4a and S4b). Similarly, we detected multiple short processes originating from Ire1α KO somata (Fig. S4c), as opposed to bipolar control neurons (Fig. S4d) using expansion microscopy (ExM). We noted no change of Satb2 expression in neurons derived from E14.5 control and KO progenitors (Fig. S4e), indicative of specific temporal context for Ire1α-regulated neuronal subtype diversity.

To study the identity of excessive processes specified by KO neurons, we immunostained the EUE-transfected control or iCre-expressing Ire1αf/f cells (Fig. S4f) for axonal and dendritic markers at DIV4 (Fig. S4g)30. Ire1α KO neurons either failed to specify an axon or projected multiple axons, as compared to polarized control cells (Fig. S4h). Where present, KO axons were shorter (Fig. S4i) and more branched (Fig. S4j). Ire1α KO neurons with no axons exhibited increased dendritic branching, possibly implicating an axon-to-dendrite identity switch in single neurites. Axon-possessing KO neurons exhibited normal dendritic tree (Fig. S4k and l). Morphological defects in the KO were associated with somatic distribution of ER tubules visualized by EGFP-Sec61β expression as compared to its polarized localization to neurites in control cells (Fig. S4m and n). This indicates a possible involvement of Ire1α in ER-driven neuronal polarization.

At DIV6, axons of control neurons were enriched for Tau-1 (Fig. S5a), Ankyrin G (Fig. S5b), and voltage-gated Na+ channels (Navs; Fig. S5c), in contrast to Ire1α KO neurons with perinuclear somatic localization of these axonal markers. Current clamp recordings from Ire1αf/f autaptic hippocampal neurons infected with lentiviruses encoding for EGFP or Cre showed a higher number of action potentials (APs) generated upon lower current injections (Fig. S5d and e), implicating more axon initial segments (AIS) specified by KO neurons and/or their altered molecular composition. Importantly, overall membrane integrity and conductance of Ire1α KO neurons were unaltered (Fig. S5f and g).

Moreover, the aberrant lamination of E14.5 progenitor-derived cortical neurons (Fig. S6a) was associated with loss of bipolar morphology (Fig. S6b–d). Regarding the molecular mechanism of polarity disruption, we corroborated previously reported altered localization and expression level of Filamin A23 (Fig. S6e), and found loss of acetylated and tyrosinated microtubules from the soma and the longest neurite (Fig. S6f and S6g), as well as increased fraction of neurons with fragmented Golgi apparatus30 (Fig. S6h and i), misaligned with the emerging longest neurite at DIV252 (Fig. S6j-S6l). Altogether, loss of bipolar morphology in developing Ire1α KO neurons is associated with defects in axon-dendrite polarity, increased current sensitivity, altered dynamics of microtubules, and localization of Golgi apparatus.

Ire1α alters cell cycle dynamics of the cortical progenitors

Because of our findings in multipotent early progenitors, as well as VZ expression of active Ire1α (Fig. 5 and S3), we then investigated the dynamics of the cell cycle in the cortical progenitors upon Ire1α KO. To label proliferating progenitors, we first pulsed thymidine analog incorporating into the DNA of dividing cells bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) at E12.5 (Fig. S7a-S7g) and E14.5 (Fig. S7h–m) and quantified the proportions of Satb2 and CTIP2-expressing neurons at P2 (Fig. S7n), when neurogenesis is complete. Among all cells born at E12.5, we counted fewer Satb2+ and more CTIP2+ cells (Fig. S7b and S7c) in the cKO, consistent with our IUE experiments using Ire1αf/f line (Fig. 5o). Moreover, in E14.5 BrdU-pulsed P2 cKO cortices, we found more BrdU+/CTIP2+ cells than in control (Fig. S7h and S7i), which localized to the top of the CP, at the expense of BrdU+/Satb2+ neurons (Fig. S7j–l).

Next, we analyzed the formation of CTIP2-positive and Tbr1-positive lineages in control and cKO cortices using BrdU pulse at E11.5, E12.5 and E14.5 (Fig. S7o–v). One day after the pulse, we detected a higher proportion of CTIP2+ neurons born at E11.5 and E14.5. Additionally, we found an increased proportion of cells which exited the cell cycle in the E13.5 cortex. To visualize the dynamics of the cell cycle upon disruption of Ire1α, we also introduced a Cre-sensitive Fucci2aR (F2aR) transgene32 to the Ire1αf/f; Emx1Cre/+ mouse line. This way, we quantified a higher proportion of Venus-labeled S, G2 and M phase progenitors, as well as mCherry-expressing postmitotic neurons in the E14.5 cortex upon Ire1α cKO (Fig. S7s and t), in accordance with our BrdU pulse-chase experiments (Fig. S7a and u). These data altogether indicate a critical requirement of Ire1α for the correct proportion between Satb2- and CTIP2-expressing neurons in a mechanism regulating the cell cycle of cortical progenitors.

Ire1α controls the synthesis of the ribosomal constituents and proteins involved in protein translation in the developing forebrain

During the UPR, robust cellular reprogramming is driven by Ire1α signaling network53,54. Ire1α activation is paralleled by suppression of general translation55. We hypothesized that also during development, Ire1α influences protein translation to regulate key developmental milestones. To test this, we purified actively translating ribosomes ex vivo in forebrain-specific Ire1α cKO56. Sucrose density gradients revealed higher level of polysomes in cKO cortices (Fig. 6a). Importantly, in the CP of Ire1α cKO, we corroborated fewer Satb2-expressing neurons to the benefit of CTIP2-positive ones (Fig. S8a and b), as well as morphological abnormalities similar to ones observed in the IUE experiments presented in Ire1αf/f line on Fig. S4a and d (Fig. S8c and d).

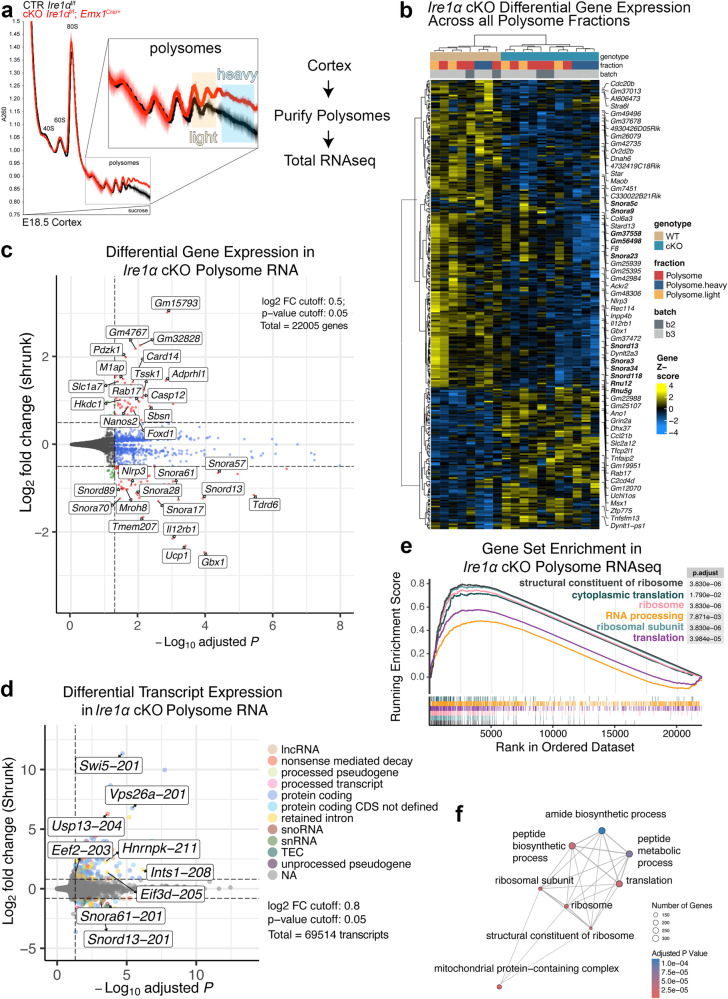

Fig. 6. Polysome-enriched transcripts in Ire1α cKO encode proteins regulating constituents of the ribosome and protein translation machinery.

a Analytic density gradient fractionation of A260-normalized E18.5 neocortex lysates, measuring the relative abundance of ribosomal subunits, 80S ribosomes, and polysomes. A260 curves plotted as mean ± S.D. across replicate fractionations in one experimental batch, baseline (1.0) centered at onset of 40S peak. b Differential Gene Expression across all polysome fractions in Ire1αf/f control (WT) and Ire1αf/f; Emx1Cre/+ (cKO) cortices. In bold are small nucleolar RNAs and components of spliceosome. c Volcano plot summarizing the Differential Gene Expression in control and cKO polysome RNAs. Indicated are hits with altered expression levels between genotypes. d Volcano plot summarizing Differential Transcript Expression in control and cKO polysome RNAs. e Top GSEA plots for cKO polysome RNA fraction versus control polysome RNA fraction. f Enrichment map visualization of cellular processes represented by significantly changed transcripts within the polysome fractions between control and cKO cortices. For statistics, we used DESeq2 which employs the Wald test to test the null hypothesis that gene expression in a generalized linear model fit with a negative binomial distribution is zero, and adjusts p values using the Benjamin Hochberg (BH) procedure. Unique genes with adjusted p values < 0.05 and log2foldchange > 0.5 were determined to be differentially expressed. For detailed datasets, refer to Supplementary Data S4 and to Data Availability section for the information on data deposition.

We then investigated the RNAs that localize to polysome fraction in Ire1α cKO cortex. RNA sequencing in bulk cortex of the control and cKO did not reveal gross changes in the transcriptome (Fig. S8e). Next, we performed two types of analyses in polysome-bound RNAs of control and cKO cortices. Differential Gene Expression (DGE) detected changes in the abundance of small nucleolar or spliceosomal RNA and transcripts encoding for core components of rRNA processing, among others (Fig. 6b, c, Supplementary Data S4). Given the disruption of the RNase domain in our cKO and the ability of this Ire1α domain to catalyze mRNA decay49 and splicing57, we also analyzed and Differential Transcript Expression (DTE) and found differences in the abundance of intron-retained transcripts coding for proteins involved in ribosome assembly, splicing and protein translation initiation and elongation, among others (Fig. 6d, Supplementary Data S4).

Polysome-associated RNAs in Ire1α cKO cortices encoded structural components of the ribosome, cytoplasmic translation and ribosomal subunits, revealed by the Gene Set Enrichment analysis (Fig. 6e and f, Supplementary Data S4). These results indicate that Ire1α loss in the cortex alters translation of RNAs crucial for ribosome complex function.

Activation of UPR, triggered by Ire1α, leads to translational shutdown in cellular efforts to restore protein homeostasis58. We next assayed translational repression upon Ire1α disruption in non-stressed conditions, using in situ run-off assays in primary cortical cultures followed by puromycilation59. Using this assay, we detected an increase in ribosome stalling in the cKO neurons, indicating Ire1α-mediated regulation of translation in basal conditions (Fig. 7a and b).

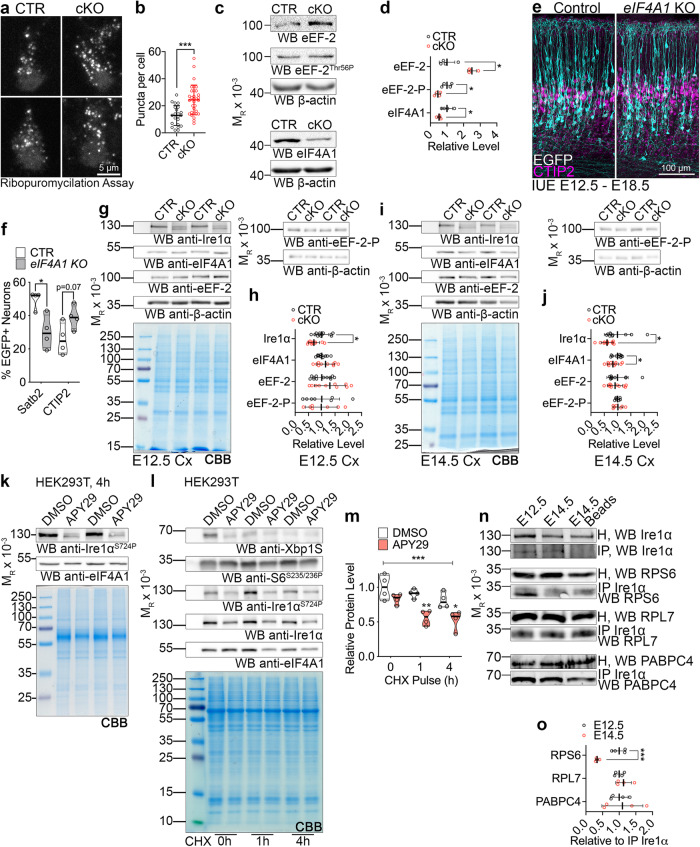

Fig. 7. Ire1α-mediated regulation of protein translation in the developing cortex.

a Images of representative primary cortical neurons prepared from Ire1αf/f (CTR) or Ire1αf/f; Emx1Cre/+ (cKO) cortices after ribopuromycilation assay to label stalled ribosomes. b Quantification of ribosome stalling in (a). c Representative Western blotting results using the control and Ire1α cKO E18.5 cortical lysates. d Quantifications of the protein level from c. Representative images of immunostaining against EGFP and CTIP2 in E18.5 coronal cortical sections of wild-type embryos after IUE at E12.5 with gRNAs and Cas9 nickase to achieve indicated genotypes. f Quantification of neuronal cell identity in the experiment in (e). g–j Representative Western blotting results using the control and Ire1α cKO cortical lysates at indicated developmental stages and quantification of protein levels. Note that the quantification for Ire1α levels in (h) is identical with Fig. 5l. Coomassie brilliant blue, CBB. k Representative Western blotting results of HEK293T cells after 4 h pulse with indicated compound. l-m Representative Western blotting of CHX pulse experiment in HEK293T treated with indicated compounds and quantification. n Representative Western blotting results of endogenous Ire1α co-immunoprecipitation (IP) from E12.5 and E14.5 cortical homogenates (H). j Interaction between Ire1α and indicated proteins was quantified relative to the amount of immunoprecipitated Ire1α. Graphs represent data points and averages ± S.D. Thick lines on violin plots represent median, thin lines represent quartiles. CBB, Coomassie Brilliant Blue stain to visualize proteins in SDS-PAGE gels. Statistics for b, d, f, h, j and o D’Agostino-Pearson normality test; for b unpaired t-test, ncells for CTR = 22 and for cKO=32 from three independent cultures, p < 0.0001; d Mann–Whitney test, ncortices for CTR = 4 and for cKO=4, for eEF-2, p = 0.0286; for eEF-2-P, p = 0.0286; for eIF4A1, p = 0.0286; f unpaired t-test, for Satb2 counts, nbrains for CTR = 4 and for KO = 4, p = 0.0140, and for CTIP2 counts, nbrains for CTR = 4 and for KO = 4, p = 0.0691; h Mann–Whitney test, for Ire1α, ncortices for CTR = 12 and for cKO=10, p = 0.0169; for eIF4A1, ncortices for CTR = 12 and for cKO=10, p = 0.3463; for eEF-2, ncortices for CTR = 12 and for cKO = 10, p = 0.2276; for eEF-2-P, ncortices for CTR = 7 and for cKO = 7, p > 0.9999; j unpaired t-test, for Ire1α, ncortices for CTR = 10 and for cKO = 11, p = 0.0284; for eIF4A1, ncortices for CTR = 10 and for cKO = 11, p = 0.0494; for eEF-2, ncortices for CTR = 10 and for cKO = 11, p = 0.5561; for eEF-2-P, ncortices for CTR = 7 and for cKO=7, p = 0.8440; m two-way ANOVA with Šidák multiple comparisons test, n = 4 biological replicates, p < 0.0001; o unpaired t-test, ncortices for E12.5 = 4 and for cKO=4; for RPS6, p = 0.0.0007, for RPL7, p = 0.3751, for PABPC4, p = 0.7826. Statistical tests were two-sided. 0.01 <* p < 0.05; 0.001 <** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

Given robust Ire1α-driven regulation of polysome-bound RNAs converging on cytoplasmic translation, as well as specific translation of protein synthesis machinery (Fig. 6f), we measured the steady-state expression levels of translation initiation and elongation regulators in control and cKO cortices (Fig. S9a and b). We identified upregulated level of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF-2), downregulated level of phosphorylated eEF-2 on Thr56, and decreased level of eukaryotic initiation factor 4A1 (eIF4A1) in the Ire1α cKO cortex (Fig. 7c and d).

We then overexpressed eEF-2 using IUE in E12.5 and E14.5 wild-type embryos (Fig. S9c–h). Four days later, we detected no alteration of Satb2 expression in the neuronal progeny after eEF-2 OE (Fig. S9d and e), but a mild neuronal lamination defect, similar to Ire1α KO (Fig. S9f–h), linked to enhanced cell cycle exit one day after IUE (Fig. S9o and p). Next, we inactivated eIF4A1 using CRISPR-Cas9 technology (Fig. 7e), which allows for simultaneous sgRNA and humanized Cas9 nickase delivery to the developing E12.5 progenitors60,61. We corroborated the efficiency of sgRNA targeting eIF4A1 (Fig. S9k and S9l). The loss of eIF4A1 resembled Ire1α KO (Fig. 5) regarding the types of neurons generated, with less Satb2-expressing neurons, at the expense of CTIP2-positive cells (Fig. 7e and f). Notably, the onset of eIF4A1 downregulation in Ire1α cKO was detectable in E14.5 cortical bulk homogenate (Fig. 7g–j). Interestingly, simultaneous eEF-2 OE and eIF4A1 KO resulted in the highest proportion of E14.5 progenitor derived neurons without an axon (Fig. S9i and j) reminiscent of Ire1α KO neurons (Fig. S4f).

Both eIF4A1 and eEF-2 were detected throughout the neurogenic stages in cortical homogenates (Fig. S9m) and highly and homogenously expressed in the E12.5 cortex, and to a lesser extent at E14.5 (Fig. S9n). Using fluorescence activated cell sorting, we purified FlashTag-positive (FT+) apical radial glia19 and verified the expression of cap-dependent translation initiation factors eIF4A1 and eIF4A2, as well as Ire1α in E14.5 cortical progenitors (S9q–t).

Because of Ire1α-dependent sorting of intron-retaining transcripts to polysomes (Fig. 6d), as well as loss of S724 phosphorylation, implicated in regulation of mRNA stability and splicing47,49 (Fig. 5k), we next hypothesized that Ire1α controls the proteostasis of eIF4A1, leading to its diminished levels (Fig. 7c and d). To mimic the molecular landscape after disruption of Ire1α, we inhibited the S724 phosphorylation using APY2947 (Fig. 7k). CHX pulse chase experiments showed that APY29-mediated inhibition of Ire1α resulted in eIF4A1 destabilization (Fig. 7l and m).

Next, we investigated the developmental stage-specific association of Ire1α with the ribosome. Using co-immunoprecipitation in E12.5 and E14.5 cortical homogenate, we quantified that endogenous Ire1α interaction with ribosomal protein S6, (RPS6), was significantly stronger at E12.5 (Fig. 7n and o). Binding to the large ribosome subunit protein RPL7 and interactor of mRNA poly(A) tail PABPC4 was not developmentally regulated. These results suggest a specific requirement for a stronger interaction between Ire1α and RPS6 at the onset of neurogenesis.

Altogether, these findings demonstrate that ribosome-associated Ire1α controls expression levels of translation regulators and proteostasis of eIF4A1.

Ire1α is a regulator of protein translation rates

Increased polysome level in the Ire1α cKO may represent ribosomes elongating more slowly or stalling, and thus accumulating in the heavy fraction (Fig. 7a and b)62. To further explore this hypothesis, we examined translation rates in Ire1α cKO using FUNCAT28,29. We first investigated protein synthesis rates in early E12.5 multipotent neuronal progenitors able to generate diverse lineages using EUE-mediated Cre delivery to induce Ire1α loss. At DIV1, we quantified lower translation rates in Cre-expressing Ki67-positive63 Ire1α KO progenitors as compared to EGFP-expressing Ire1αf/f ones (Fig. 8a and b). Similarly, we detected lower translation rates in E12.5 mitotic progenitors upon loss of eIF4A1 (Fig. 8c and d). We quantified approximately 50% lower rates of translation in DIV4 upper layer Ire1α cKO E14.5 progenitor-derived neurons as compared to control cells (Fig. 8e and f). To study the rate of translation in vivo, we introduced the MetRS* transgene to the Ire1αf/f; Emx1Cre/+ line. After exposure to ANL and click chemistry with biotin-alkyne, we demonstrated largely reduced ANL incorporation in E14.5 cKO cortices as compared to Ire1αf/+; Emx1Cre/+ heterozygotes (Fig. S10). Taken together, Ire1α loss engenders a decrease in the rate of protein synthesis in the developing cortex.

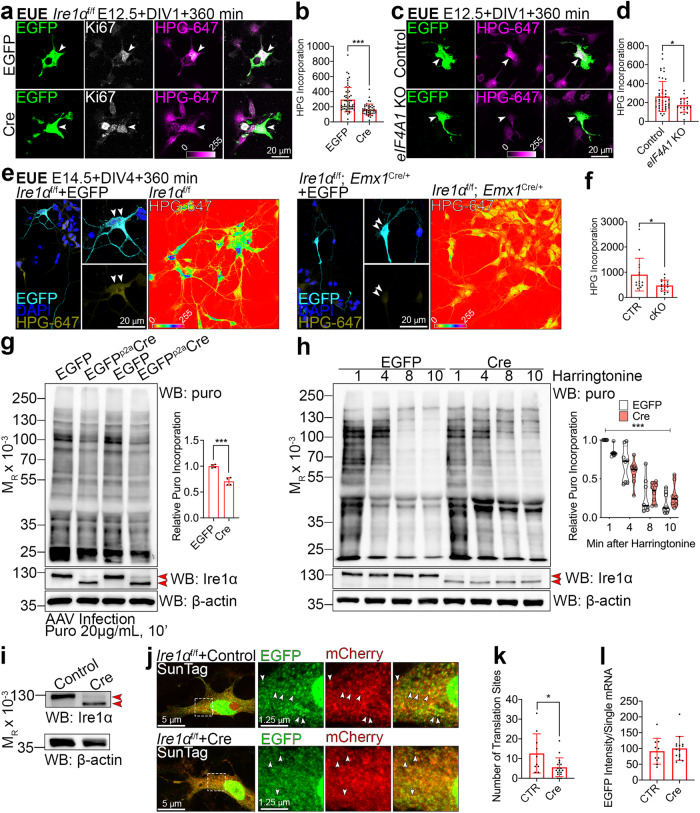

Fig. 8. Loss of Ire1α leads to diminished translation rates as an effect of slower elongating ribosomes and fewer translation sites.

a, c, e Images of representative primary cortical neurons prepared from Ire1αf/f a wild-type c or control and Ire1α cKO e embryos after ex utero electroporation (EUE) at E12.5 (a and c) or E14.5 e with indicated plasmids. Neurons were fed L-homopropargylglycine (HPG) for 360 min prior to fixation at DIV1 or DIV4. HPG was detected with Sulfo-Cyanine5 azide. e Right panels: images of HPG incorporation in control and cKO primary DIV4 neurons prepared from E14.5 cortex. White arrowheads point to Ki67-positive progenitors (a and c) or to somata of neurons derived from E14.5 progenitors (e). b, d, f Quantification of HPG incorporation. g Representative Western blotting using DIV5 lysates from Ire1αf/f mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) after metabolic labeling of protein synthesis using puromycin (puro) and its quantification. MEFs were infected at DIV0 with control or Cre-expressing AAVs. Red arrowheads point to wild-type and KO form of Ire1α. h Representative Western blotting results of ribosome run-off assay using puromycin in control and KO MEFs at indicated timepoints after harringtonine treatment and quantification. i Western blotting validation of Ire1α KO in AAV-infected MEFs for the SunTag reporter experiment. j Representative images of empty and Cre-encoding virus infected MEFs expressing the SunTag24x-BFP-PP7 reporter. k Active translation sites were quantified in fixed MEFs. l Quantification of the intensity of scFv-GFP at translation sites. Bar graphs represent data points and averages ± S.D. Violin plot on h represents individual data points, thick line median and thin lines quartiles. Statistics for b, d, f, k, l D’Agostino-Pearson normality test; for b Mann-Whitney test, ncells for EGFP = 58 and for Cre = 42 from three independent cultures, p < 0.0001; d Mann–Whitney test, ncells for Control=54 and for Cre=21 from three independent cultures, p = 0.0291; f Mann-Whitney test, ncells for EGFP = 15 and for Cre=19 from three independent cultures, p = 0.0169; g Shapiro-Wilk and unpaired t-test, four independent cultures, p = 0.0003; h two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test, eight independent experiments, p < 0.0001; k Mann–Whitney test, ncells for CTR = 10 and for Cre=17 from three independent cultures, p = 0.0438; l unpaired t-test, ncells for CTR = 10 and for Cre=15 from three independent cultures, p = 0.58. Statistical tests were two-sided. 0.01 <* p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001.

To further investigate the mechanism of such regulation, we took advantage of ribosome run-off experiments with harringtonine64. To circumvent confounding effects of varying translation rates in cortical cell types (Figs. 1–4), we infected Ire1αf/f MEFs with control or Cre-encoding AAVs and kept in culture for DIV5 (Fig. S3a and b). We first measured protein synthesis in MEFs using puromycin33 and found that Ire1α KO cells showed its reduced incorporation (Fig. 8g). Ire1α KO cells also showed diminished response to the harringtonine treatment, which might be attributable to slowly elongating ribosomes (Fig. 8h).

Next, we used SunTag65 to label single mRNAs and visualize translation in control and Cre-infected fixed Ire1α KO MEFs (Fig. 8i). To study translation dynamics in cells, mCherry-fused PP7 bacteriophage coat protein is used to identify mRNAs and the EGFP-tagged single chain variable fragment recognizing the SunTag allows to detect the synthesis of nascent proteins. As compared to control, Ire1α KO MEFs demonstrated fewer colocalizing EGFP and mCherry puncta, reflective of decreased number of mRNA molecules in translation (Fig. 8j–l). Altogether, we conclude that lower translation rates upon Ire1α KO are associated with slower ribosome elongation rates and decreased number of active translation sites.

Non-canonical role of Ire1α in developing cortex

Next, we tested if disruption of Ire1α engenders alteration of UPR components expression. Immunostaining for the molecular off-switch for cytoplasmic translation eIF2α and its Ser52 phosphorylation showed homogenous expression across E12.5 cortex and a mild enrichment in the CP neurons at E14.5 (Fig. S11a), an expression pattern different from the one of Ire1α (Fig. 5). Further, quantification of ER stress marker levels66,67, eIF4A2 and JNK2 immunostaining revealed no gross differences between control and cKO cortices (S11b–d). Finally, using IUE in E13.5 cortices, we mimicked the UPR activation by co-expressing the phosphorylation-deficient S52D variant of eIF2α (S11e) in the cells electroporated with shRNA to knock-down endogenous eIF2α and showed a generalized defect in neuronal differentiation and diminished CP entry (Fig. S11f and g), rather than specific effects on Satb2 and CTIP2 (Fig. 5n and o). These results suggest that cortical cell diversity is regulated by specific translation pathways, including among others, a non-canonical, UPR-independent Ire1α signaling.

eIF4A1 helicase activity regulates Satb2 mRNA translation during development

Given the critical requirement for high protein synthesis rates in neuronal progenitors of later lineages (Fig. 1) and the regulation of global mRNA translation by Ire1α and eIF4A1, we investigated the mechanisms of Ire1α-mediated regulation of Satb2 expression.

Translational control of eIF4A1 requires 5’UTR embedded elements, like G-quadruplexes (G4s) in the mRNA68,69. We first quantified the highest number of predicted G4s in Satb2 mRNA among classical neuronal fate determinants (Fig. S12a–d). We hypothesized that increased G4s in Satb2 makes its mRNA translation uniquely sensitive to eIF4A1 and thereby also Ire1α level.

We first constructed fluorescence-based translational reporters by fusing 5’UTRs of Satb2 and CTIP2 to EGFP ORF. In these reporters, quantification of EGFP fluorescence intensity is a measure of 5’UTR-dependent translation efficiency. Next, we co-electroporated each reporter with CRISPR-Cas9 plasmids to induce eIF4A1 KO in E12.5 cortical progenitors. At E16.5, we observed decreased Satb2 reporter translation efficiency (Fig. 9a and b) and increased CTIP2 reporter translation efficiency (Fig. 9c and d), associated with lower Satb2 expression in CTIP2 reporter-expressing KO neurons (Fig. 9e, f). We detected minor effects using the reporters in eIF4A1 KO and Ire1α KO at E14.5 (Fig. S12e–h).

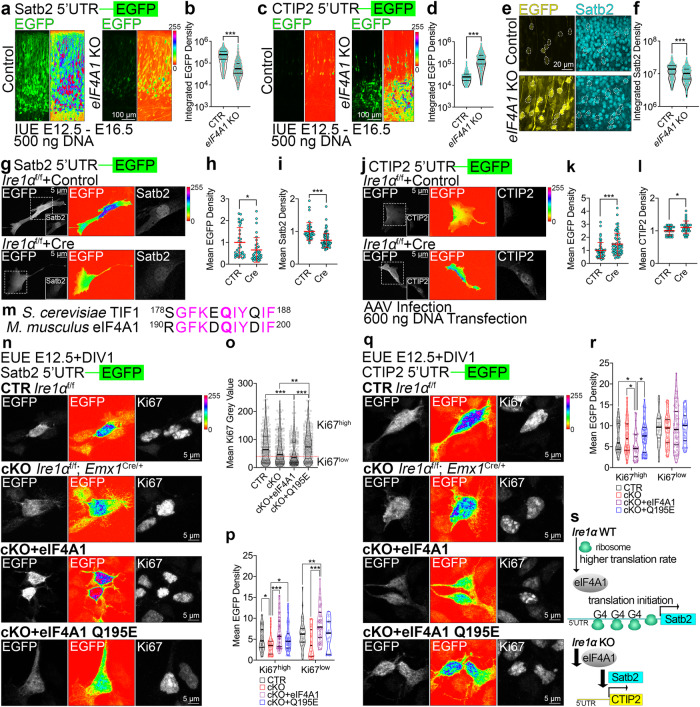

Fig. 9. Helicase activity of eIF4A1 and Ire1α are indispensable for translation of Satb2 in cortical lineages.

a, c Representative images of EGFP fluorescence signals in the E16.5 brain sections after IUE at E12.5 with CRISPR-Cas9 vectors to achieve indicated genotypes and Satb2 5’UTR a or CTIP2 5’UTR c translation reporter construct. Shown are the native signals (left panels) and intensity encoding (right panels). b, d Quantification of EGFP fluorescence signals in single cells expressing translation reporters of Satb2 5’UTR b or CTIP2 d. e, f Representative images and quantification of CTIP2 5’UTR translation reporter construct and anti-Satb2 immunolabeling (compare c, d). g–l Representative images of EGFP fluorescence signals (left panels: gray scale, middle panels: intensity encoding) and immunostaining for Satb2 g or CTIP2 j in Ire1αf/f MEFs infected with Control or Cre-encoding AAVs at DIV0. At DIV5, infected MEFs were transfected with indicated reporter constructs, fixed and immunostained at DIV6. h, k Quantification of EGFP mean fluorescence signals of 5’UTR Satb2 reporter h or CTIP2 (k). i, l Quantification of mean nuclear fluorescence signals after immunostaining for Satb2 i or CTIP2 (l). m Sequence alignment of yeast TIF1 and murine eIF4A1. In bold the Q residue crucial for helicase activity. n–r Early cortical progenitors of indicated genotypes were transfected with EUE with Satb2 n or CTIP2 q translational reporter, as well as indicated constructs. At DIV1, cells were fixed and immunolabeled against EGFP and Ki67. o Quantification of overall Ki67 fluorescence intensity in analyzed cells. p, r Quantification of translational reporter fluorescence in Ki67 expression level-dependent manner. s Current model of Ire1α and eIF4A1 interplay in regulation of neuronal cell diversity in the cortex. Violin plots depict median, interquartile range (box) and minimum and maximum value (whiskers). Red line and error bars on h, i, k, l indicate mean ± S.D. For statistical analyses, b, d, f, h,i, k, l D’Agostino and Pearson normality test and Mann-Whitney test; o, p, r D’Agostino and Pearson normality test and Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s correction. For b, d, f p < 0.0001; for exact p values in o, p, r refer to Supplementary Fig. 1. For h ncells for CTR = 33 and for Cre = 35, p = 0.0105; i ncells for CTR = 39 and for Cre = 85, p < 0.0001; k ncells for CTR = 53 and for Cre = 58, p = 0.0003; l ncells for CTR = 30 and for Cre = 30, p = 0.0388. Results on h-i and k-l represent quantifications from three independent cultures. Statistical tests were two-sided. 0.01 <* p < 0.05; 0.001 <** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

We observed analogous effects for translational efficiencies for Satb2 and CTIP2 in Ire1α KO MEFs transfected with each reporter (Fig. 9g–l), congruent with the nuclear endogenous Satb2 and CTIP2 expression levels (Fig. 9i and l).

Finally, using EUE in early cortical progenitors from control and Ire1α cKO, we co-expressed wild-type eIF4A1and its helicase activity-deficient mutant68,70 (Fig. 9m) with either of the reporters (Fig. 9n–r). We quantified the reporter fluorescence in a Ki67 expression-specific manner (Fig. 9o) and found that wild-type eIF4A1 restored the decreased translation of Satb2 in E12.5 cKO cortical progenitors (Fig. 9p). We observed analogous effects for CTIP2 (Fig. 9r), with wild-type eIF4A1 reducing the enhanced CTIP2 translation in cKO progenitors, in contrast to its Q195E mutant.

These results indicate that eIF4A1-driven timed regulation of translation downstream of Ire1α is embedded in the 5’UTR of Satb2 (Fig. 9s).

Representative pictures for neuronal fate quantification can be found in Fig. S13 and original pictures of membranes used for representative protein biochemistry in Fig. S14.

Discussion

Development of the cortex comprises an orchestrated series of sequential, tightly controlled gene expression events with many layers of regulation. We make the surprising finding that protein synthesis rates are intrinsic features of distinct progenitor lineages and differentiated neurons (Figs. 1–4). Our data implicate the regulation of protein synthesis by a mechanism downstream of Ire1α in the specification of Satb2-positive neurons and their polarization. We report a developmental role for Ire1α beyond its canonical role in translation stress pathways.

The demand to synthesize and remodel the proteome during cortical development places homeostatic pathways on the brink of cellular stress signaling. We speculate that such demands in normal development are met by the same molecular players as stress pathways, however, likely leading to unique downstream pathways active in development. During cortical development, Ire1α safeguards the cellular translation flux by driving the expression of translation regulators, essential for the high protein synthesis rate in neuronal progenitors, enabling translation of Satb2 (Figs. 6–9).

Our translation rate measurements in cultured cortical cells enable tight control of microenvironment and identical exposure to the methionine analog (Figs. 2a and 4e). We show that cultured immature neurons at DIV1 derived from E12.5 brain translate at higher rates than ones from E14.5 brain in vitro. In P2 cortex, L5 CTIP2 neurons translate at higher levels than L2/3 Satb2 neurons, while L6 CTIP2 neurons and DL Satb2 neurons exhibit lower translation rates (Fig. 4).

It is becoming increasingly clear that, on top of elegant transcriptional regulation18,19, generation of cortical neuron diversity relies on specific pathways for translational control. According to our data, the 5’UTR in Satb2 mRNA requires activity of translation initiation complexes, comprising eIF4A1, which unwind cap-proximal regions of mRNA, especially ones with G4s, prior to its ribosomal loading71. In line with this are our observations on decreased translation rates upon eIF4A1 KO (Fig. 8) associated with defects in specification of Satb2-expressing neurons (Fig. 7). Loss of eIF4A1 or Ire1α leads to a decreased translation efficiency of Satb2 reporter. On the other hand, the CTIP2 reporter is translated more efficiently, associated with lower Satb2 expression in neurons (Fig. 9f).

Global attenuation of translation during the UPR is linked to PERK-mediated phosphorylation of eIF2α at Ser5272. The stress response alters the cellular translation machinery and its affinity towards ORFs of specific type, position, and secondary structures73,74. We report that loss of Ire1α results in lower rates of protein synthesis in neuronal progenitors and neurons, independently of eIF2α, or its canonical downstream splicing client Xbp1 (Figs. S3, S9 and S11). Ire1α regulates the amount of translating polysomes, with their higher abundance in the cKO. In the context of lower translation flux, this represents ribosome stalling (Figs. 6 and 7) and/or slower elongation (Fig. 8), reminiscent of observations in Huntingtin mutants62. As Ire1α binds 80S ribosomes directly with high affinity (Fig. 7n, o and25), and is in the vicinity of the ribosomes embedded in the ER by the translocon, it is well positioned to impact protein synthesis directly during cortex development. The interaction between Ire1α with small ribosomal subunit is strong at E12.5, when multipotent progenitors able to generate Satb2- and CTIP2-expressing neurons are present in the cortex (Fig. 7n, o).

Apart from being a site of protein synthesis, the ER has been also reported as an organelle crucial for neuronal polarization75. Upon Ire1α KO, we report a mislocalization of the ER to the polarizing neurite (Fig. S4). Defects in axon formation, and thus axonal targeting of Tau-1, AnkG and Navs (Fig. S5) might indicate ER dysfunction upon Ire1α loss, implicating its role in ER integrity and neuronal polarization76. Disrupted polarity in Ire1α KO neurons (Fig. S4) is associated with the loss of ER-dependent microtubule stability and Golgi apparatus (Fig. S6), overall leading to altered current sensitivity (Fig. S5). It is tempting to speculate that the role of Ire1α in regulating the generation of Satb2-expressing neurons is molecularly intertwined with the axon formation, given the conservation of differentiation programs across neuronal lineages19,77.

Taken together, our study reinforces the powerful impact of post-transcriptional mechanisms in cortex development. Translational regulation of gene expression during neuronal specification is layered on top of transcriptional mechanisms, many of which have been highlighted in excellent recent works18,19. Modulation of translation rates may be a particular requirement for cortical neuron diversification, evolving as a mechanism to specify upper layers in the late stages of development. In our comparative proteomics, we identify many cellular pathways, of which the effector proteins are specifically translated in early and later-born neuronal lineages (Fig. 3). It is foreseeable that other translational regulators alongside Ire1α drive the increased translation efficiency in progenitors of later-born upper layer neurons. Hence, translational control is deployed in normal development and on a par with protein degradation orchestrates the neuronal diversification and wiring of the mammalian cortex. Importantly, it has become evident that the RNA transcripts are not the principal determinants of protein abundance and cellular fate in developmental systems78–80.

Methods

Animals

Mouse (Mus musculus) lines described in this study have been maintained in the animal facilities of the Charité University Hospital and Lobachevsky State University. Mice were housed in a 12 h light/dark cycle at 18-23 degrees of Celsius, 40-60% air humidity, with pellet food and water available ad libitum. Mice were used at embryonic (E), or postnatal (P) stages, as reported for each experiment. Each sample included both sexes within litters without distinctions. Wild-type mice were of NMRI strain. Females were housed in groups of up to five animals per cage. Males were single housed from the point of exposure to female animals. In Ire1αf/f mouse line48, exons 20-21 of Ire1α were engineered to be flanked by loxP sites. To inactivate Ire1α in the developing cortex, we crossed Ire1αf/f mice with the Emx1Cre/+ line, in which Cre recombinase is expressed from the Emx1 gene allele (Gorski et al., 2002). As described in our previous work, for the breeding we exclusively used Ire1αf/f males and Ire1αf/f; Emx1Cre/+ females to circumvent leaky expression of Cre81. Ire1αf/f; Emx1Cre/+ was further crossed to MetRS* mouse line36 and to Fucci2aR mouse line32. Animals homozygous for the loxP alleles in both lines were viable, fertile, born at the expected Mendelian ratio, and exhibited no overt phenotypic changes in the cage environment. For experiments with tdTomato reporter, Satb2Cre/+39 males were mated to NMRI wild-type females. The date of vaginal plug was counted as E0.5. All mice were sacrificed by administering a lethal dose of pentobarbital.

Inclusion and ethics statement

MCA is a signatory of the ALBA Declaration on Equity and Inclusion. All experiments were performed in compliance with the guidelines for the welfare of experimental animals approved by the State Office for Health and Social Affairs, Council in Berlin, Landesamt für Gesundheit und Soziales (LaGeSo), permissions G0079/11, G0206/16, G0184/20, G0054/19, G0055/19, and by the Ethical Committee of the Lobachevsky State University of Nizhny Novgorod.

Sex and age/developmental stage of animals for in vivo experiments

Littermates of both sexes were randomly assigned to experimental groups during experimental procedures or collection of embryonic tissue. Developmental stages or stages at experimental interventions are listed on the figures or in the figure legends.

Murine primary cortical cultures

Embryonic brains were dissected in ice-cold Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) under stereomicroscope to collect cortices in 5 mL of ice-cold 0.25% trypsin (Gibco) solution. After incubation at 37 °C for 20 min with occasional swirling, tissue digestion was terminated by addition of 1 mL of fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco). Further, 1U of DNaseI (Roche) was added to the tube for 1 min. Next, cortices were carefully washed twice with 5 mL of pre-warmed (37 °C) Complete Neurobasal medium and triturated in 1 mL Complete Neurobasal medium using P1000 and P200 pipette tip. Cells were counted with Naubauer counting chamber and seeded in 24 well-plate formats at 120,000 cells (EUE) or 240,000 cells (after nucleofection) per coverslip in 1 mL of Complete Neurobasal medium. Glass coverslips were coated with poly-L-lysine (70,000–150,000, 0.01%, P4707, Sigma) and laminin (from Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm murine sarcoma basement membrane, L2020, Sigma) dissolved in PBS. The day of neuronal prep was counted as day in vitro 0 (DIV0). Cells were cultivated at 37 °C in the presence of 5% carbon dioxide in HERA-cell240 (Heraeus) incubator. For the experiments with DMSO and CHX, cortical cultures were treated with the assayed compound two hours post-plating. Autaptic hippocampal cultures were prepared from P0-P2 Ire1αf/f mice82.

Complete neurobasal

500 mL Neurobasal (Gibco, Life Technologies), 10 mL B-27 (Gibco, Life Technologies), 5 mL GlutaMAX (Gibco, Life Technologies), 5 mL penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies, Gibco), 1 mL Primocin (Invitrogen).

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from Ire1αf/f mice

MEFs were collected from E13.5 Ire1αf/f embryos. Briefly, abdominal wall was dissected, minced with a sterile razor blade and incubated with 1 mL 0.25% trypsin (Gibco) at 37 °C for 30 minutes. Trypsinization reaction was terminated by addition of 4 mL MEF medium and the tissue was triturated 20 times to release single cells. Cellular suspension was transferred to T75 flask with 15 mL of fresh MEF medium and cells were incubated until confluency. Cells were split according to standard cell culture protocols. Cell cultures were expanded and frozen at passage five, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored until use at −80 °C. Before each experiment, correct genotype of the fibroblasts was validated using the DNA isolated from the cell suspension according to the genotyping protocol for Ire1α. MEFs were infected using AAVs according to standard infection protocols. Given that the primary fibroblasts come from randomly assigned embryos, these cells contain clones from both sexes.

MEF medium

A total of 500 mL DMEM (Life Technologies), 50 mL FCS (Gibco), 5 mL penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies, Gibco), 5 mL GlutaMAX (Gibco).

Cell lines

HEK293T, Neuro-2A, and NIH3T3 cells lines were from DSMZ and were maintained in the standard medium (MEF medium). The cells were routinely tested negative for mycoplasma contamination prior to the experiments.

Molecular cloning strategies for constructs generated in this study

Cloning of all expression vectors in this study was performed using the NEBuilder system according to the manufacturer’s protocol (New England BioLabs). DNA fragments were amplified using GXL Prime Star DNA polymerase (Takara) using cDNA libraries or donor plasmids as templates. Destination vectors were linearized with EcoRI-HF (New England BioLabs).

pRai-HA-IRE1α

Human IRE1α cDNA (NM_001433.3) was amplified from plasmid template [Addgene, #1300983], using the following oligos: 5’- agattacgctatctgtacaggcATGCCGGCCCGGCGGCTG-3’ and 5’- ggccgctagcccgggtaccgCTTGGTTTGGGAAGCCTGGTCTCCCTGC-3’ and inserted into the modified pRaichu vector31.

pCAGIG-6XHis-eEF2

Murine eEF2 cDNA (NM_007907.2) was amplified from cDNA library using the following oligos: 5’-gtctcatcattttggcaaagATGCATCATCATCATCATCATGTGAACTTCACAGTAGATC-3’ and 5’-cggccgcgatatcctcgaggCTACAGTTTGTCCAGGAAGTTG-3’ and inserted into pCAGIG vector for simultaneous expression of 6XHis-tagged eEF2 and EGFP.

pCAG-5’UTR-Satb2 and -CTIP2 reporter

Satb2 and CTIP2 5’UTR sequences were amplified using a mouse embryonic cDNA library and Prime Star GXL polymerase. An existing pCAG-IRES-tdTom vector was linearized using EcoRI digestion and PCR-amplified fragments were inserted and fused together with a GFP coding sequence. Primers for PCR had the following sequences: 5’UTR Satb2_fwd, 5’-gtctcatcattttggcaaagCGCCCCCATCATCATAAC-3’; 5’UTR Satb2_rev, 5’-ccttgctcacCATGCTGCTCCGATTTGG-3’; GFP_fwd, 5’-gagcagcatgGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAG-3’; GFP_rev, 5’-cggccgcgatatcctcgaggTTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATG-3’; 5’UTR CTIP2_fwd, 5’-gtctcatcattttggcaaagAATTTATTTTAGCCTTTTCTCTATTTTAGAGCAAG-3’; 5’UTR CTIP2_rev, 5’-ccttgctcacCATTGCCCCGGCATCTATTC-3’; GFP_fwd, 5’-cggggcaatgGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAG-3’; GFP_rev, 5’-cggccgcgatatcctcgaggTTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATG-3’. The fragments were recombined with the vector backbone using NEBuilder system. After that, the 5’UTR fragments fused to GFP and IRES sequence were shuttled to a pCAG vector84 and fused with dsRed encoding sequence also using NEBuilder system.

eIF2α variant replacement experiment

eIF2α was knocked down using a pLKO Sigma Mission plasmid system. The genetic replacement was carried out using co-transfection of the pLKO and the human eIF2α, its phosphorylation-deficient S52A or -mimic S52D, which were gifts from David Ron purchased from Addgene (#21807, http://n2t.net/addgene:21807; RRID: Addgene_21807; #21808, http://n2t.net/addgene:21808; RRID: Addgene_21808; #21809, http://n2t.net/addgene:21809; RRID: Addgene_21809).

eIF4A1 and translational rescue experiment using the 5’UTR Reporters

The helicase activity-reduced Q195E variant70 of eIF4A1 were gifts from Hans-Guido Wendel (Addgene plasmid #70044, http://n2t.net/addgene:70044; RRID: Addgene_7004468) purchased from Addgene.

The wild type eIF4A1 was extracted from murine cDNA library using the PCR with the following primers: 5’-gtctcatcattttggcaaagATGgactacaaagacgatgacgacaagTCTGCGAGTCAGGATTCTC-3’ and 5’-cggccgcgatatcctcgaggTCAAATGAGGTCAGCAACGTTG-3’ and cloned into pCAG expression vector using EcoRI restriction digest and NEBuilder system.

pCAG-Xbp1S

The wild type Xbp1S was extracted from murine cDNA library using the PCR with the following primers: 5’-atctgtacagaattcggtaccATGGACTACAAAGACGATG-3’ and 5’-gcggccgctagcccgggtacTTAGACACTAATCAGCTGG-3’ and cloned into pRai expression vector using EcoRI restriction digest and NEBuilder system.

pCAG-IRE1α S724F

Mutagenesis of pcDNA3.1-IRE1α was performed using Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit and primers 5’-GGGCAGACACgctTTCAGCCGCCG-3’ and 5’-ACTGCCAGCTTCTTGCAG-3’ and the resulting mutated IRE1α sequence was cloned into pCAG vector using NEBuilder strategy.

Lentivirus and AAV production and infection of autaptic hippocampal cells

Production of lentiviral particles and infection of autaptic cultures for electrophysiology was performed by the Charité Viral Core Facility. For other experiments in this report, we used pAAV-CAG-EGFP, pAAV-CAG-iCre-p2a-EGFP-WPRE, pAAV-CAG-iCre-WPRE3, and pAAV-CAG-WPRE3 particles.

Electrophysiological recordings

Voltage and current clamp experiments were performed according to our previously published works85 using autaptic hippocampal neurons from P0-P2 Ire1αf/f infected with the control and Cre-encoding lentiviral particles84 produced by the viral core facility of the Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed on the autaptic cultures at room temperature at DIV12-20. Synaptic currents were recorded using a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Axon Instruments) controlled by Clampex 9.2 software (Molecular Devices). Membrane capacitance and series resistance were compensated by 70%, and data was filtered by a low-pass Bessel filter at 3 kHz and sampled at 10 kHz using an Axon Digidata 1322A digitizer (Molecular Devices). Neurons were perfused (SF-77B, Warner Instruments) with the extracellular solution (in mM): 140 NaCl, 2.4 KCl, 10 HEPES (Merck), 10 glucose (Carl Roth), 2 CaCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA), and 4 MgCl2 (Carl Roth) (~300 mOsm; pH7.4). Somatic patches were carried out using borosilicate glass pipettes, with a tip resistance of 2-3.5 MOhm and filled with the following internal solution (in mM): 136 KCl, 17.8 HEPES, 1 EGTA, 4.6 MgCl2, 4 Na2ATP, 0.3 Na2GTP, 12 creatine phosphate, and 50 U/ml phosphocreatine kinase (~300 mOsm; pH7.4). Data were analyzed using AxoGraph software.

Nucleofection of primary neurons

Transfection of primary cortical cells was performed using nucleofection (Lonza Bioscience) according to the manufacturer’s instructions38. Primary cortical cells isolated from murine embryos were transfected using the Amaxa Mouse Neuron Nucleofector Kit (Lonza, VPG-1001). After the trituration, cell concentration was determined using the Neubauer chamber. For the nucleofection, we used 1 μg DNA per 1 million cells. Accounting for cell death, we plated 120,000 cells per well of 24 well plates for immunocytochemistry and 240,000 per well of 24 well plates for biochemical assays.

Small molecule inhibitor screening

Right after trituration, E13.5 embryonic cortical cells prepared from Satb2Cre/+ mice, were nucleofected with pCAG-EGFP and pCAG-loxP-Stop-loxP-tdTomato plasmids and seeded at 120,000 cells per well of 96-well plate. Two hours post-plating, cultures were treated with compounds at two concentrations, in technical duplicates. Cells were then cultivated until DIV2, when the proportion of Satb2tdTom neurons normalized to EGFP positive cells was determined using FACS38. TdTom+ (Q2 + Q4) cell count was divided by the number of EGFP (Q1 + Q2) expressing cells and then normalized to the “Untreated” condition. For the detailed result per inhibitor, refer to Supplementary Data S3.

Ex utero electroporation (EUE)

DNA solution (final concentration of 500 ng/μL) was microinjected into the lateral embryonic ventricles, followed by electroporation using 6 pulses of 35 V applied using platinum electrodes. Right after the electroporation, the isolated tissue was placed in ice cold HBSS until proceeding with primary cultures.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells cultured on coverslips were fixed with cold (4 °C) 4% PFA and 4% sucrose (Merck) PBS solution for 20 minutes at room temperature, washed three times with PBS and incubated with Blocking buffer for 30 minutes. Next, cells were incubated with primary antibodies diluted with blocking buffer accordingly for 16–20 h at 4 °C with moderate shaking, followed by washing 3 times with PBS. Further, secondary antibodies coupled to appropriate fluorophore diluted in blocking buffer were applied for 2 hours at room temperature. After washing 3 times with PBS, coverslips were briefly rinsed with ddH2O and mounted on Superfrost Plus glass slides (Thermo Scientific) with Immu-Mount mounting medium (Shandon, Thermo-Scientific).

Blocking buffer

5% horse serum (Gibco, Life Technologies), 0.3% Triton X-100 (Roche), in PBS buffer.

Puromycin labeling in MEFs

To metabolically label proteins using puromycin, we used day-in-vitro 5 (DIV5) Ire1αf/f mouse embryonic fibroblasts infected with AAV particles (Charité Viral Core Facility) encoding for EGFP (control) and EGFP-p2a-Cre at DIV0. Cells were incubated with 20 μg/mL puromycin (Sigma) for 10 minutes33. The cells were washed with PBS and lysed in 1X Laemmli sample buffer at 70 °C for 20 minutes. Proteins were then resolved with SDS-PAGE and analyzed using Western blotting with anti-puromycin antibody (Millipore). The puromycin incorporation was normalized to the protein loading amount, visualized by Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB), or an appropriate loading control.

Puromycilation in primary cortical cultures