Abstract

Background

To report a case of Multiple Evanescent White Dot Syndrome (MEWDS) one month after a COVID-19 infection in a female patient at an age unusual for the occurrence of this disease.

Case presentation

A 69-year-old Caucasian female reported the presence of floaters, photopsia, and enlarging vision loss in her left eye following the COVID-19 infection. Clinical and multimodal imaging was consistent with the MEWDS diagnosis. Fluorescein angiography examination revealed characteristic hyperfluorescent spots around the fovea in a wreath-like pattern. An extensive lab workup to rule out other autoimmune and infectious etiologies was inconclusive. Visual acuity and white dots resolved after a course of corticosteroids, which was confirmed on follow-up dilated fundus exam and multimodal imaging.

Conclusions

MEWDS is a rare white dot syndrome that may occur following COVID-19 infection in addition to other reported ophthalmic disorders following this infection.

Keywords: Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome, COVID-19 infection, White dot syndrome, Retina, Ophthalmology, Case report

Introduction

Multiple Evanescent White Dot Syndrome (MEWDS) is a rare, acute-onset inflammatory disease of the choroid and retina characterized by yellow-white dots at the level of the outer retina or retinal pigment epithelium. MEWDS typically affects young and middle-aged women and presents with unilaterally blurred vision, photopsia, floaters, and restricted visual field [1]. MEWDS has an excellent prognosis with complete recovery of vision and visual fields within a few months with rare recurrence. It develops after a viral prodrome around thirty percent of the time [2]. MEWDS pathogenesis is still unknown, but it is thought to be an ocular immune-mediated disorder in patients of specific genetic disposition. Vaccinations have also induced MEWDS in some rare cases, including the mRNA coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) vaccination in several case reports [3–7]. COVID-19 infection-related conjunctivitis, vision changes, irritation, and subconjunctival hemorrhage have been reported, but there are few reports of COVID-19 causing MEWDS [8]. Here, we report a case of MEWDS one month after a COVID-19 infection in a female patient at an age unusual for the occurrence of this disease.

Case presentation

A 69-year-old Caucasian woman presented with new ocular symptoms in her left eye, which started about ten weeks before attending our uveitis clinic in March 2023. She was symptomatic with new floaters and central flashing, and about four weeks later, she developed an enlarging scotoma and progressive vision loss. The patient was diagnosed with a COVID-19 infection via antibody testing four weeks before the current onset of ocular symptoms, along with fever, congestion, and cough. The patient had previously received the COVID-19 vaccination several months before contracting COVID-19 infection. Aside from asthma, hypothyroidism, and headaches, her past medical history and family history were unremarkable and negative for prior autoimmune disease.

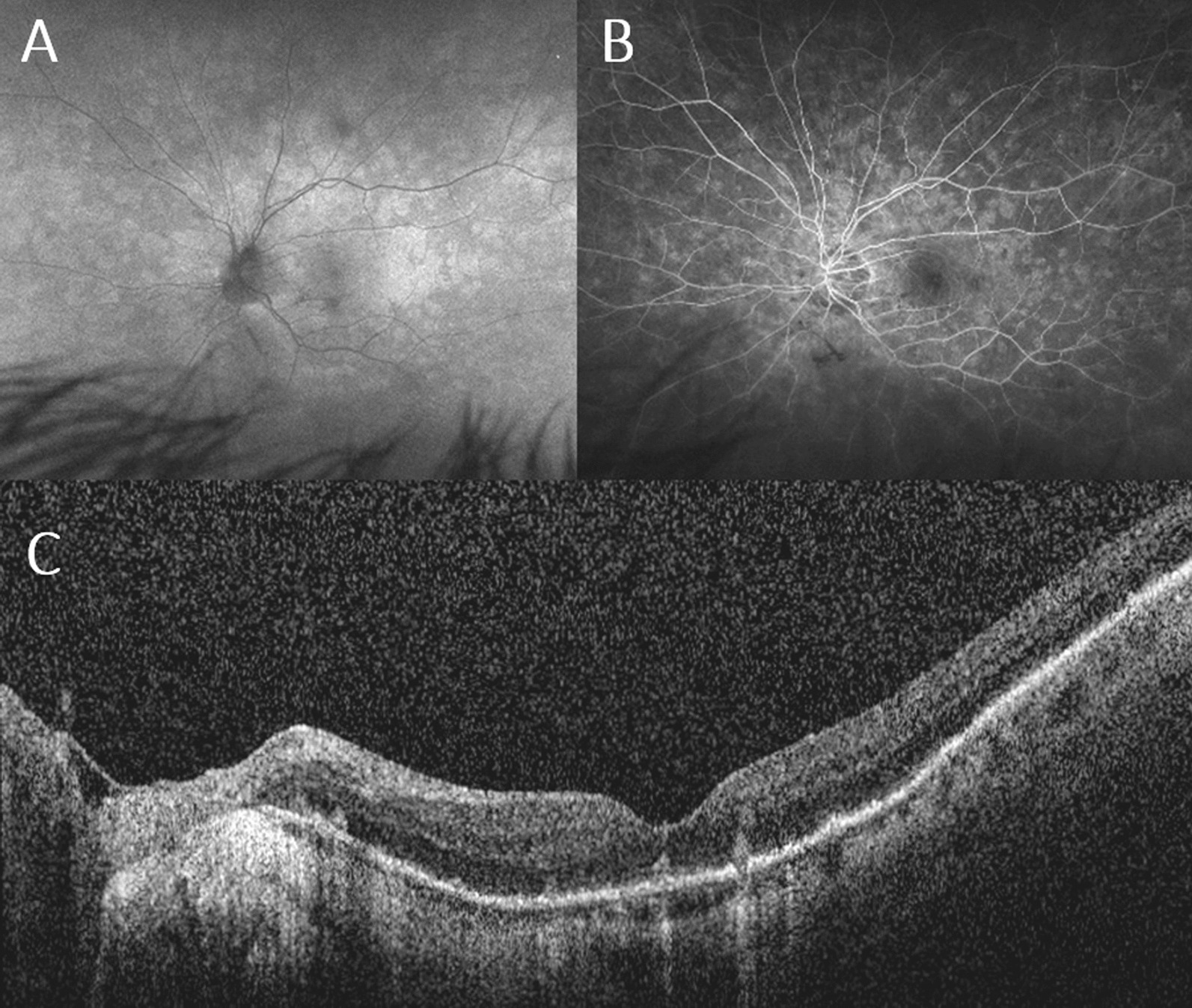

A complete eye examination was performed with macular optical coherence tomography (OCT), fundus autofluorescence (FAF), and fluorescein angiography (FA) tests. ICG angiography was not done due to iodine allergy. The best corrected visual acuity was 20/30 in the right eye and 20/80 in the left eye. There was no relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD). The ocular exam exhibited PVD with moderate vitreous inflammation and a quiet anterior chamber in the left eye. No sign of intraocular inflammation was detected in the right eye. The other ocular exam findings included bilateral mild nuclear cataract, myopic refractive error with mild myopic retinal degeneration. FAF showed peripapillary and macular hyper-autofluorescent spots in the posterior pole (Fig. 1A). These spots co-localized to punctate hyperfluorescent areas on FA, arranged in a wreath-like pattern with nearly well-defined borders (Fig. 1B). OCT examination featured disruption of the ellipsoid zone (EZ) and hyper-reflective subretinal deposits in the affected left eye (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Multimodal imaging at the initial presentation. A Fundus autofluorescence (FAF) left eye at presentation demonstrating peripapillary and macular hyper autofluorescence extending to the equator. B Fluorescein angiography (FA) at presentation with hyperfluorescent in a wreath-like pattern corresponding to areas of hyper-autofluorescence on FAF. C Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography (EDI OCT) at presentation showing hyperreflective subretinal deposits and significant ellipsoid zone disruption

Serum testing was conducted to rule out other possible etiologies. Complete blood count (CBC) and complete metabolic panel (CMP) were normal. QuantiFERON-TB Gold (QFT), angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) test, lysozyme blood test, HLA-B29 serotyping, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test (FTA-ABS) were all negative. C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) levels were slightly elevated compared to reference values.

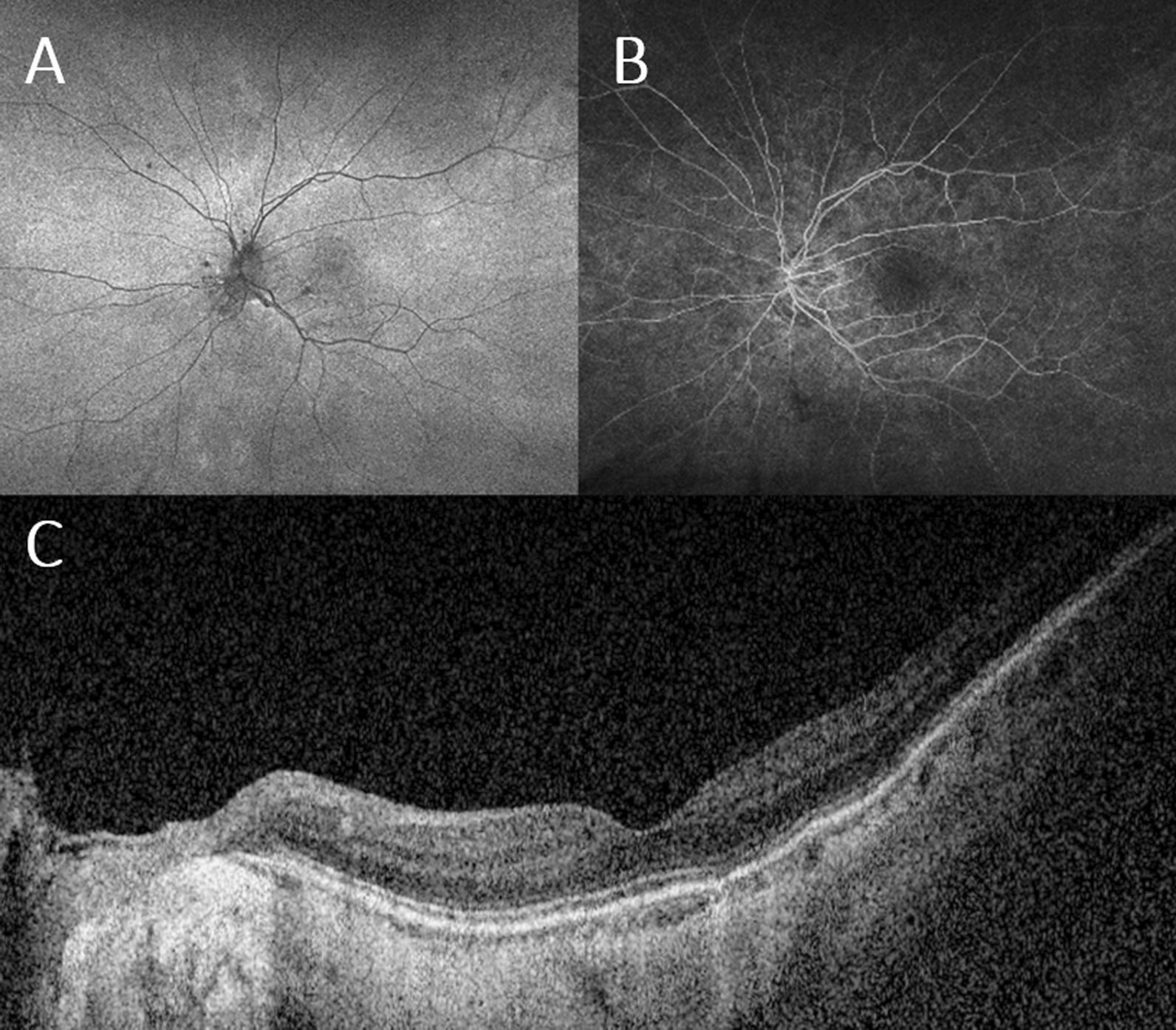

We determined that the patient’s constellation of symptoms and characteristic imaging findings were consistent with MEWDS. The patient was prescribed a tapering course of oral steroids (Prednisone 40 mg daily for a week with a 10 mg weekly taper). At a 10-day follow-up from the presentation, the patient had no adverse events. The photopsia improved, and she had a visual acuity of 20/70 in the left eye. Hyperreflective subretinal deposits on OCT were reduced in size and number, and vitreous inflammation slightly improved. One month after the presentation, eye visual acuity improved to 20/50 and remained stable at the three-month follow-up visit. FAF and FA showed a significant improvement in peripapillary and macular autofluorescent spots and hyperfluorescent patterns, respectively (Fig. 2A, B). The ellipsoid zone was restored, and hyper-reflective deposits were resolved on OCT (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Multimodal imaging at Follow-up. Fundus autofluorescence (FAF) at one-month follow-u with significant improvement in peripapillary and macular hyper-autofluorescence. Fluorescein angiography (FA) at a 3-month follow-up shows resolution of wreath-like pattern hyperfluorescence in the 2-min frame. Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography (EDI OCT) at presentation showing improvement of hyperreflective subretinal deposits and integrity of ellipsoid zone

Discussion

We presented a 69-year-old myopic female patient who developed MEWDS following a COVID-19 infection. Differentials for MEWDS include other white dot syndromes, mainly acute zonal occult outer retinopathy (AZOOR) and acute macular neuroretinopathy (AMN). AZOOR and AMN were less probable diagnoses, given the resolution of the ocular symptoms and improved imaging findings. Vitreoretinal lymphoma was also considered as a possible differential diagnosis but ruled out given the rapid resolution of symptoms and posterior segment findings and response to oral steroids.

COVID-19 infection has been associated with various retinal and uveal disorders, typically weeks after onset of COVID-19 symptoms [9]. There are not many reported MEWDS cases post-COVID-19 infection, though there are multiple reported cases post-COVID-19 vaccination [10]. The mechanism of action of COVID-19 in the pathogenesis of ocular disorders such as MEWDS is still being debated. One proposed mechanism of action is through angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 targeting SARS-CoV-2 on vascular endothelial cells, leading to impeded blood barrier function, disturbance of intercellular junctions, and cellular swelling [11]. Studies suggest that patients' retinal arteries and veins post-COVID infection sustain microvascular damage compared to unexposed patients [12, 13]. Disruptions in retinal peripapillary circulation are thought to contribute to the development of MEWDS [11]. Although the pathogenesis is still highly debated and relatively unknown, there are some associations of MEWDS with the HLA-B51 subtype. [14]

MEWDS is typically managed with observation as it is self-resolving. Oral corticosteroids can be considered if significant visual impairment is prolonged [15]. Recurrence of MEWDS is uncommon at a rate of about 14%, and most cases resolve spontaneously within a few weeks [1]. We started oral steroids for our patient, given her symptoms had been existing for ten weeks when she attended our clinic. Although the ocular symptoms and exam findings showed a significant improvement ten days after the start of oral steroid, it might have happened without this treatment, given the benign course of this disease.

The oldest patient featured on a case report of COVID-19 infection and MEWDS association was a 47-year-old female, and the oldest with COVID-19 vaccination and MEWDS association was a 67-year-old female. [5, 16]. Our case features a patient outside the typical age range of 20–40 years but follows the expected unilateral manifestation. To our knowledge, this is the oldest patient with a reported case of MEWDS associated with COVID-19 infection.

Conclusion

MEWDS is a rare white dot syndrome that might be associated with both COVID-19 vaccination and infection. This is one of many ophthalmic disorders reported following COVID-19 infection.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- MEWDS

Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 19

- PVD

Posterior vitreous detachment

- OCT

Optical coherence tomography

- FAF

Fundus autofluorescence

- FA

Fluorescein angiography

- RAPD

Relative afferent pupillary defect

- EZ

Ellipsoid zone

- CBC

Complete blood count

- CMP

Complete metabolic panel

- QFT

QuantiFERON-TB Gold

- ACE

Angiotensin-converting enzyme

- ANCA

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

- RPR

Rapid plasma reagin

- FTA-ABS

Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- ESR

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- AZOOR

Acute zonal occult outer retinopathy

- AMN

Acute macular neuroretinopathy

Author contributions

MT drafted the original manuscript. JH and JL made significant contributions to the subsequent revisions of the manuscript drafts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study received no funding or grant support.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publications

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The following authors have nothing to disclose: MT, JH, and JL.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Papasavvas I, Mantovani A, Tugal-Tutkun I, Herbort CPJ. Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome (MEWDS): update on practical appraisal, diagnosis, and clinicopathology; a review and an alternative comprehensive perspective. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2021;11(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s12348-021-00279-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.dell’Omo R, Pavesio CE. Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome (MEWDS) Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2012;52(4):221–8. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e31826647ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inagawa S, Onda M, Miyase T, et al. Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome following vaccination for COVID-19: a case report. Medicine. 2022;101(2):e28582. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000028582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomishige KS, Novais EA, Finamor LPDS, Nascimento HMD, Belfort R., Jr Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome (MEWDS) following inactivated COVID-19 vaccination (Sinovac-CoronaVac) Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2022;85(2):186–189. doi: 10.5935/0004-2749.20220016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yasuda E, Matsumiya W, Maeda Y, et al. Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome following BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2022;26:101532. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2022.101532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sriwijitalai W, Wiwanitkit V. Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome (MEWDS) and inactivated COVID-19 vaccination. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2022;85(4):426. doi: 10.5935/0004-2749.2022-0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soifer M, Nguyen NV, Leite R, Fernandes J, Kodati S. Recurrent multiple evanescent white dot syndrome (MEWDS) following first dose and booster of the mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine: case report and review of literature. Vaccines. 2022;10(11):1776. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10111776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng Y, Park J, Zhou Y, Armenti ST, Musch DC, Mian SI. Ocular manifestations of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in a tertiary care academic medical center in the United States: a cross-sectional study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:1551–1556. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S301040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sen M, Honavar SG, Sharma N, Sachdev MS. COVID-19 and eye: a review of ophthalmic manifestations of COVID-19. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69(3):488–509. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_297_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain A, Shilpa IN, Biswas J. Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome following SARS-CoV-2 infection—a case report. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70(4):1418–1420. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_3093_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adzic Zecevic A, Vukovic D, Djurovic M, Lutovac Z, Zecevic K. Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome associated with coronavirus infection: a case report. Iran J Med Sci. 2023;48(1):98–101. doi: 10.30476/IJMS.2022.95007.2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Invernizzi A, Torre A, Parrulli S, et al. Retinal findings in patients with COVID-19: results from the SERPICO-19 study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;27:100550. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Østergaard L. SARS CoV-2 related microvascular damage and symptoms during and after COVID-19: consequences of capillary transit-time changes, tissue hypoxia and inflammation. Physiol Rep. 2021 doi: 10.14814/phy2.14726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borruat FX, Herbort CP, Spertini F, Desarnaulds AB. HLA typing in patients with multiple evanescent white dot syndrome (MEWDS) Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 1998;6(1):39–41. doi: 10.1076/ocii.6.1.39.8084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi Y, Ataka S, Wada S, Kohno T, Nomura Y, Shiraki K. A case of multiple evanescent white dot syndrome treated by steroid pulse therapy. Osaka City Med J. 2006;52(2):83–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smeller L, Toth-Molnar E, Sohar N. White dot syndrome report in a SARS-CoV-2 patient. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2022;13(3):744–750. doi: 10.1159/000526090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.