Abstract

The undivided double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) genome of Helminthosporium victoriae 190S virus (Hv190SV) (genus Totivirus) consists of two large overlapping open reading frames (ORFs). The 5′-proximal ORF encodes a capsid protein (CP), and the downstream, 3′-proximal ORF encodes an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RDRP). Unlike the RDRPs of some other totiviruses, which are expressed as a CP-RDRP (Gag-Pol-like) fusion protein, the Hv190SV RDRP is detected only as a separate, nonfused polypeptide. In this study, we examined the expression of the RDRP ORF fused in frame to the coding sequence of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) in bacteria and Schizosaccharomyces pombe cells. The GFP fusions were readily detected in bacteria transformed with the monocistronic construct RDRP:GFP; expression of the downstream RDRP:GFP from the dicistronic construct CP-RDRP:GFP could not be detected. However, fluorescence microscopy and Western blot analysis indicated that RDRP:GFP was expressed at low levels from its downstream ORF in the dicistronic construct in S. pombe cells. No evidence that the RDRP ORF was expressed from a transcript shorter than the full-length dicistronic mRNA was found. A coupled termination-reinitiation mechanism that requires host or eukaryotic cell factors is proposed for the expression of Hv190SV RDRP.

Helminthosporium victoriae 190S virus (Hv190SV) belongs to the genus Totivirus in the family Totiviridae. Members of the family Totiviridae have undivided double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) genomes packaged in isometric particles 40 to 50 nm in diameter (7). Hv190SV infects the phytopathogenic fungus Helminthosporium victoriae, the causal agent of Victoria blight of oats. The virus and its associated satellite dsRNAs have been implicated in a debilitating disease of its fungal host (5). Purified Hv190SV virions, like those of other dsRNA mycoviruses, are noninfectious in conventional infectivity assays. Therefore, studies on Hv190SV genome expression and structure-function relationships have relied on the use of heterologous systems, including bacterial and baculovirus expression systems (9, 10, 24).

Like those of other totiviruses, the genome of Hv190SV contains two large overlapping open reading frames (ORFs) coding for a capsid protein (CP) and an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RDRP). The 5′ end of the positive strand of the dsRNA genome is uncapped and highly structured and contains a relatively long (289 nucleotides [nt]) 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR) with two noninitiator AUGs. The 5′ UTR is postulated to function as an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) which directs the translation of the upstream ORF, encoding the CP, by a cap-independent internal initiation mechanism (9). Evidence that the 5′ UTR of another totivirus, Leishmania RNA virus 1 (LRV1), contains an IRES element has been presented (20). The downstream ORF of the Hv190SV dsRNA genome, encoding the RDRP, is in a −1 frame with respect to the CP ORF, and its translational start codon (nt 2605 to 2607) overlaps the stop codon for the upstream CP ORF (nt 2606 to 2608) in the tetranucleotide sequence 2605-AUGA-2608. Hv190SV RDRP is detectable as a separate, nonfused virion-associated minor component (9). The RDRP ORF has been expressed in bacteria from its initiator AUG at nt 2605 to 2607, and the expression product has been shown to be indistinguishable in size and serological reactivity from the virion-associated RDRP (9).

The mechanism by which the downstream RDRP is expressed from the dicistronic genome of Hv190SV has not been elucidated. In some totiviruses, including those infecting yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae L-A virus [ScV-L-A] and ScV-L-BC) and protozoa (Giardia lamblia virus and Trichomonas vaginalis virus), RDRP is expressed only as a CP-RDRP fusion protein via a −1 (or +1) ribosomal frameshift mechanism (12, 17, 21, 28). The CP-RDRP fusion protein is detectable as a virion-associated minor protein. Sequence analysis and secondary-structure predictions of the overlap region between the CP and RDRP ORFs in the yeast and protozoan totiviruses indicate the presence of a consensus heptameric slippery site and a pseudoknot structure. Both the slippery site and pseudoknot have been shown to be essential for frameshifting in ScV-L-A, the type species of the genus Totivirus (2, 27). As for Hv190SV, previous studies showed no evidence for the presence of the CP-RDRP fusion protein in virions or infected fungal isolates (9). This observation, coupled with the lack of structures resembling the consensus ribosomal slippery site and predicted pseudoknot in the overlap region between the two ORFs, suggests that Hv190SV RDRP may be expressed via a mechanism different from that reported for the totiviruses infecting yeast and protozoa.

In this study, we examined the expression of RDRP in two heterologous systems. Monocistronic constructs containing the CP or RDRP ORF fused in frame to the reporter gene encoding the green fluorescent protein (GFP), as well as the dicistronic construct CP-RDRP:GFP, were generated for expression in bacteria and Schizosaccharomyces pombe. We demonstrate that RDRP is expressed in S. pombe, but not in bacteria, from the downstream ORF in the dicistronic construct as a separate nonfused polypeptide. We show that, similar to that in the fungal host, the expression level of RDRP in S. pombe is low, and we discuss the mechanism(s) by which the downstream RDRP ORF is expressed from the Hv190SV dicistronic genome.

RDRP is expressed from monocistronic, but not dicistronic, constructs in bacteria.

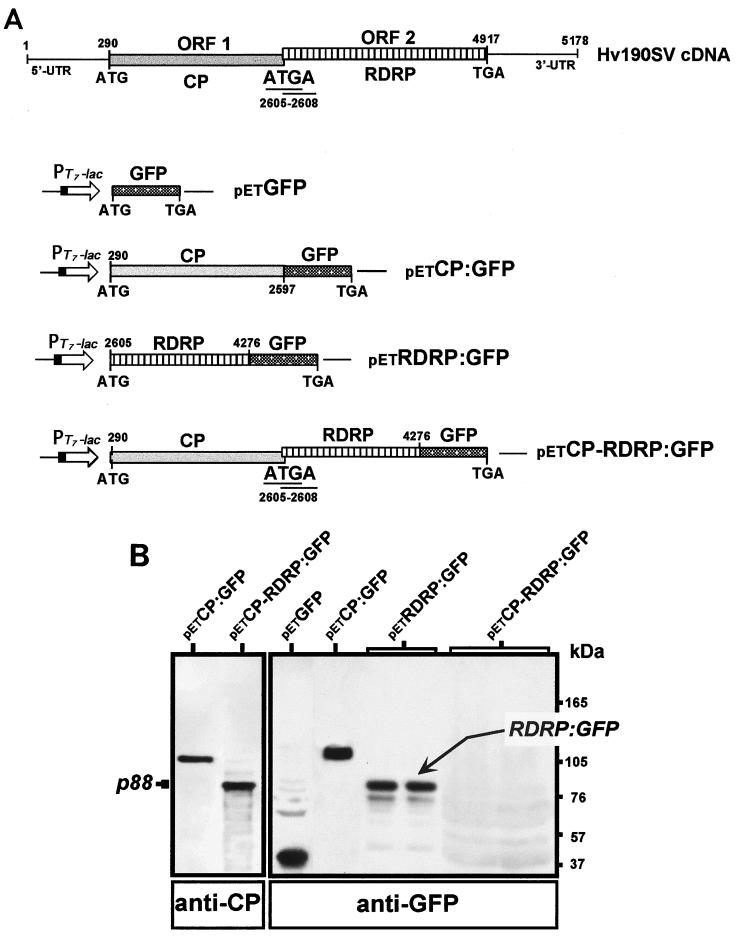

Constructs for bacterial expression of the GFP gene or in-frame fusions of the GFP gene to Hv190SV CP- and RDRP-coding sequences were generated in the expression vector pET 22(b)+ or pET 21(d)+ (Novagen) (Fig. 1). Construct petGFP was obtained by subcloning the EcoRI-SstI fragment containing the entire GFP ORF (from plasmid pZ-GFP) in EcoRI- and SstI-digested vector pET 22(b). Construct petCP:GFP was produced by a two-step cloning procedure following PCR amplification. A fragment of the CP ORF corresponding to the C terminus with an introduced EcoRI site for subcloning of the GFP ORF in frame with the CP-coding sequence was generated by PCR. The amplification product (400 bp) was gel purified and digested with SpeI and EcoRI and cloned at the SpeI- and EcoRI-digested sites in the construct pZ-GFP to create a fragment of the CP-coding sequence fused in frame to the GFP ORF. The CP-GFP fused fragment was excised by digestion with SpeI and SstI and ligated to the SpeI-digested plasmid petHV1 (nt 2204 [Fig. 1A]) containing Hv190SV cDNA sequences from nt 290 to 5178 (Fig. 1A) (9). Construct petRDRP:GFP was created by in-frame insertion of the EcoRI-SstI fragment containing the GFP ORF into a unique EcoRI site (at nt 4276) in the RDRP ORF and the SstI site in the multiple cloning sequence of construct petHV4 (9), previously generated for the expression of the RDRP gene in pET 21(d)+ (starting at the initiator AUG beginning at nt 2605). The dicistronic construct petCP-RDRP:GFP was generated by insertion of the EcoRI-SstI fragment containing the GFP ORF into the RDRP ORF at a unique EcoRI site (nt 4276 [Fig. 1A]) in the construct petHV1 to create an in-frame fusion of the GFP gene to the sequence corresponding to the C terminus of RDRP. The CP ORF and the overlapping tetranucleotide ATGA between the CP and RDRP ORFs were maintained in the dicistronic construct petCP-RDRP:GFP. The monocistronic constructs containing the coding sequences for the GFP fusions to CP and RDRP were used as controls to verify the expression as well as the predicted sizes of the fusion products. Finally, the coding regions of all constructs generated during the course of this study were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis.

FIG. 1.

Bacterial expression of Hv190SV CP and RDRP ORFs. (A) Schematic representation of pET constructs used for expression of Hv190SV CP and RDRP ORFs. The coding sequence for GFP (750 bp) was fused in frame to the CP or RDRP ORF as a fragment corresponding to the C terminus. petCP-RDRP:GFP consists of a dicistronic construct containing both the CP and RDRP ORFs with a configuration identical to that of the Hv190SV dicistronic genome; the overlap region (ATGA; nt 2605 to 2608) between the CP and RDRP ORFs was preserved. petCP:GFP and petRDRP:GFP represent monocistronic constructs for expression of fusions of the GFP gene to either the CP or RDRP ORF and were included for comparison. Nucleotide numbering in the constructs corresponds to nucleotide positions in Hv190SV cDNA (9); nt 290 and 2605 are the first nucleotides of the initiator codons for the CP and RDRP ORFs, respectively. Construct petGFP, containing the GFP ORF (750 bp), provided a positive control for GFP expression. (B) Western blot analysis of the bacterial expression products of the Hv190SV dicistronic genome. Lysates from bacterial cells were analyzed following induction with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), by immunoblotting with antibodies against either CP or GFP by using a chemiluminescent detection kit (Phototope-HRP Western blot detection kit; New England Biolabs). Constructs petCP:GFP and petRDRP:GFP for expression of the respective GFP fusions generated predicted products of 120 and 90 kDa, respectively. Expression of the dicistronic construct petCP-RDRP:GFP produced the expected CP product of 88 kDa, corresponding to the upstream CP ORF. The product from the downstream ORF (RDRP:GFP) in the dicistronic construct was not detected (even in overloaded wells) either as a putative CP-RDRP:GFP fusion protein (predicted size of approximately 180 kDa) or as a separate RDRP:GFP product with a predicted size of approximately 90 kDa that would comigrate with the expression product from construct petRDRP:GFP.

We initially intended to monitor the expression of the GFP fusions by fluorescence microscopy. This was not possible, however, because the bacterial cells transformed with the GFP fusion constructs were nonfluorescent. The expressed CP:GFP and RDRP:GFP fusion products were largely present in an insoluble nonfluorescent form in inclusion bodies. This was determined by Western blot analysis of the soluble (supernatant) and insoluble (pellet) fractions of the bacterial lysates. The petGFP-transformed bacteria, on the other hand, expressed soluble GFP and were brightly fluorescent when examined by fluorescence microscopy. We therefore relied on Western blot analysis to examine the expression of fusion products from the various constructs using polyclonal antisera specific to Hv190SV CP (anti-CP) or GFP (anti-GFP). Western blotting was conducted as previously described (10, 24) except that immunodetection was performed with a chemiluminescence kit (Phototope-HRP Western blot detection kit; New England Biolabs) and goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G-horseradish peroxidase conjugate as the secondary antibody. Both of the fusion products CP:GFP (predicted size of 120 kDa) and RDRP:GFP (predicted size of 90 kDa), which were found in the insoluble fraction of the bacterial lysates, were expressed at high levels from their respective monocistronic constructs (Fig. 1B, lanes petCP:GFP and petRDRP:GFP).

Although the CP, expressed from the upstream ORF in the dicistronic construct petCP-RDRP:GFP, was readily detectable in immunoblots with antibodies against CP (Fig. 1B), expression of the RDRP:GFP fusion from the downstream ORF in the same construct could not be detected, even when concentrated bacterial lysates were used. The CP was detectable only as a protein band of approximately 88 kDa that comigrated with virion p88. Thus, the downstream RDRP ORF can be expressed from monocistronic, but not dicistronic, constructs in a prokaryotic system.

Hv190SV RDRP is expressed at low levels from the downstream ORF of dicistronic constructs in S. pombe.

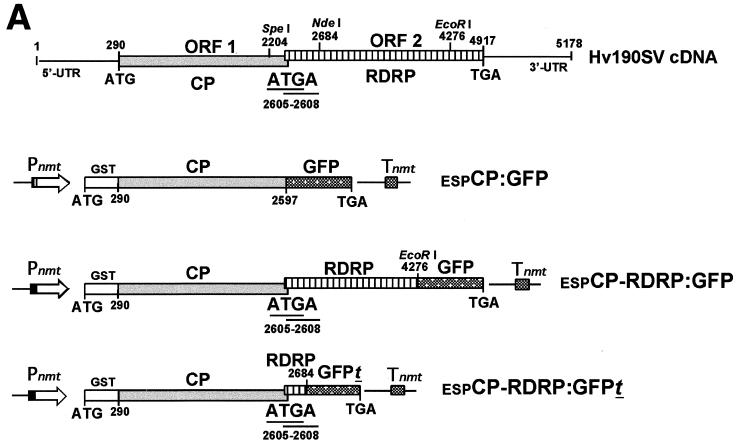

Constructs for S. pombe expression of GFP gene fusions to the coding sequences of Hv190SV CP and RDRP were generated in the transformation vector pESP-2 (Stratagene) for ligation-independent cloning (LIC) (Fig. 2A). Bacterial constructs petCP:GFP and petCP-RDRP:GFP and construct pZ-CP-RDRP:GFPt (consisting of a truncated RDRP ORF [nt 2605 to 2684] fused to the coding sequence for N-terminally truncated GFP) were used as templates along with sequence-specific LIC primers for the 5′ end of the CP ORF, starting at the CP initiation codon (LIC-CPf; 5′-GACGACGACAAGATGTCTCACACCACGATC-3′), and the region of the GFP-coding sequence corresponding to the C terminus (LIC-GFPr; 5′-CAGGACAGAGCATCATTTGTATAGTTCATCCATGCC-3′) to amplify the respective PCR products. The PCR products corresponding to the coding sequences of the CP:GFP, CP-RDRP:GFPt, and CP-RDRP:GFP fusions (with approximate sizes of 3.0, 2.9, and 5.0 kbp, respectively) were inserted via LIC into the vector pESP-2. Constructs espCP:GFP, espCP-RDRP:GFP, and espCP-RDRP:GFPt were used to transform S. pombe and expression was analyzed 16 to 18 h after induction of the nmt promoter.

FIG. 2.

Expression of Hv190SV CP and RDRP ORFs in S. pombe. (A) Schematic representation of constructs used for expression of Hv190SV ORFs in S. pombe. Constructs were generated in the transformation vector pESP-2 with gene transcription under the control of the inducible “no message in thiamine” (nmt) promoter. The GFP ORF (750 bp) was fused in frame to either the CP or RDRP ORF as described in the legend to Fig. 1. The CP ORF in all constructs is expressed as an in-frame fusion of the portion corresponding to the C terminus to the GST gene. Construct espCP-RDRP:GFP is a dicistronic construct containing both the CP and RDRP ORFs in a configuration identical to that of the Hv190SV dicistronic genome; the region of overlap between the CP start and RDRP stop codons (ATGA; nt 2605 to 2608) was preserved. espCP-RDRP:GFPt is likewise a dicistronic construct, but it contains only the first 79 nt of the RDRP ORF fused in frame to an ORF for an N-terminally truncated GFP. Nucleotide numbering in the constructs corresponds to their positions in the full-length cDNA clone of Hv190SV dsRNA (9); nt 290 and 2605 are the first nucleotides for the translation initiation codons of the CP and RDRP ORFs, respectively. (B) Detection of expression of fusions of the GFP gene to the Hv190SV CP or RDRP ORF by fluorescence microscopy. S. pombe cells transformed with construct espCP:GFP for expression of the upstream CP ORF were highly fluorescent (upper left). Cells transformed with construct espCP-RDRP:GFP showed a subtle and diffuse, but reproducible, fluorescence, indicating that translation from the downstream RDRP ORF occurred in yeast cells, albeit at a lower efficiency (lower left). Cells transformed with the espCP-RDRP:GFPt construct, which consists of the downstream ORF fusion to the gene for an N-terminal truncation of GFP (no chromophore formation is predicted), were nonfluorescent (viewed with transmitted light [upper right] and with fluorescence microscopy [lower right]). S. pombe cells were examined 18 h postinduction, after their transfer to thiamine-free culture medium, by epifluorescence microscopy with a fluorescein isothiocyanate filter (490 nm).

Expression was initially determined by visualization of GFP fluorescence with fluorescence microscopy. Yeast cells transformed with the espCP:GFP construct showed bright GFP fluorescence indicating high levels of expression, as would be expected to occur from an optimal translation initiation context in the glutathione S-transferase (GST)-CP:GFP fusion of this monocistronic construct (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, GFP fluorescence was also detectable in yeast cells transformed with the dicistronic construct espCP-RDRP:GFP (Fig. 2B). The intensity of fluorescence exhibited by those transformants, however, was markedly lower than that observed in cells transformed with construct espCP:GFP (Fig. 2B). The fluorescence results nevertheless indicated that the RDRP:GFP fusion was indeed expressed from the downstream ORF of the dicistronic construct. This subtle fluorescence was consistently observed in cells transformed with the dicistronic construct in at least five independent expression experiments. No fluorescence was detected in cells transformed with the dicistronic construct espCP-RDRP:GPFt, encoding a truncated GFP (Fig. 2B). espCP-RDRP:GPFt has a dicistronic organization similar to that of espCP-RDRP:GFP, but the RDRP ORF is translationally fused to a truncated GFP ORF predicted to be incapable of chromophore formation (26). Therefore, it served as a control for endogenous, nonspecific fluorescence. Similarly, no background fluorescence was observed in S. pombe cells transformed with the parent plasmid pESP-2 (data not shown).

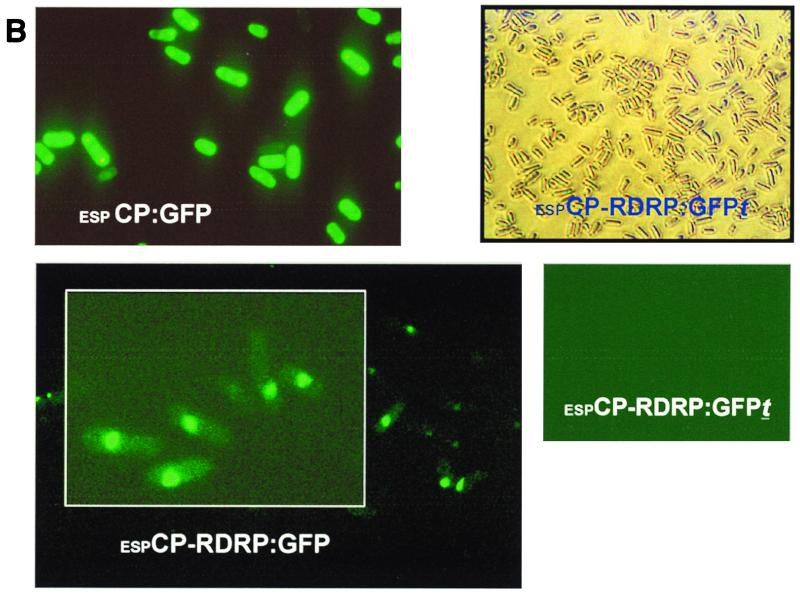

Expression of the RDRP:GFP fusion was further verified by Western blot analysis with S. pombe lysates and antibodies against GFP. In agreement with our fluorescent microscopy observations, low levels of the RDRP:GFP fusion were detected in lysates from espCP-RDRP:GFP transformants by using GFP antibodies (Fig. 3, lane espCP-RDRP:GFP). The RDRP:GFP product was evident as a faint protein band of approximately 90 kDa that comigrated with the product expressed from petRDRP:GFP in bacteria. The size of the protein band (90 kDa) is consistent with that predicted for a product translated from the initiator AUG codon of the downstream ORF starting at nt 2605 of the Hv190SV sequence in the dicistronic construct. The 90-kDa protein was detectable only in lysates from espCP-RDRP:GFP transformants. The additional protein bands visible in blots probed with the antiserum to GFP represent nonspecific products cross-reacting to GFP antibodies; those are present in the other samples, including lysates from S. pombe transformed with the parent plasmid pESP-2 (Fig. 3, lane ESP-2).

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of expression products of the Hv190SV CP and RDRP ORFs in S. pombe. Cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with polyclonal antibodies against either CP or GFP by using a chemiluminescent detection kit (Phototope-HRP Western blot detection kit). A polypeptide product of approximately 140 kDa was obtained with construct espCP:GFP. Expression of the dicistronic construct espCP-RDRP:GFP generated the expected 120-kDa CP-derived GST fusion corresponding to the translation product of the upstream ORF. The RDRP:GFP product corresponding to the translation product of the downstream ORF was detectable as a faint band corresponding to a protein of approximately 90 kDa (predicted to comigrate with the petRDRP:GFP product [Fig. 1]).

The expression of the CP-derived product as a GST-CP:GFP fusion (with a predicted size of approximately 140 kDa) was readily detectable in lysates of S. pombe transformed with the monocistronic construct espCP:GFP with antibodies specific for either CP or GFP (Fig. 3, lanes espCP:GFP). The major product (approximately 120 kDa) expressed from the dicistronic constructs espCP-RDRP:GFPt and espCP-RDRP:GFP was detected with the antibodies to CP, but not with the GFP antibodies (lanes espCP-RDRP:GFPt and espCP-RDRP:GFP). In each case, the size of products generated with these transformants was consistent with that predicted from the translation of the CP ORF fused to the GST-coding sequence (approximately 120 kDa).

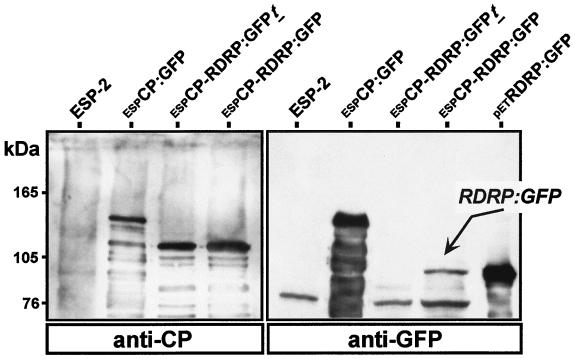

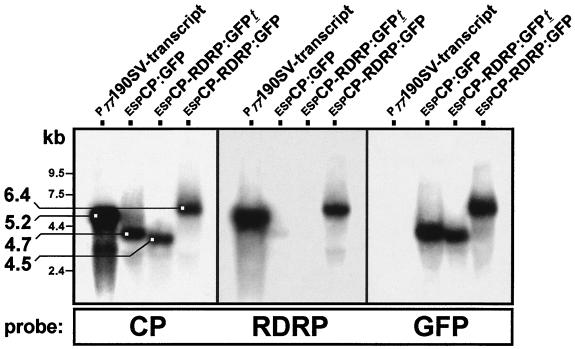

The possibility that RDRP was expressed from a shorter transcript rather than the dicistronic full-length transcript was investigated by Northern hybridization analysis. For this purpose, total RNA was isolated by the procedure of Chomczynski and Sacchi (1) from S. pombe cells transformed with various expression constructs containing Hv190SV genes. The RNA samples were electrophoresed on 1% agarose-formaldehyde gels and transferred to a nylon membrane (Hybond N+; Amersham) by alkaline blot transfer (Transblot; Schleicher & Schuell). Blots were hybridized with [α-32P]dCTP-random-primed (Megaprime; Amersham) probes for the Hv190SV CP-coding sequence (nt 234 to 2204) and the RDRP-coding sequence (nt 3735 to 4917) as well as for the GFP ORF (750 bp). The results indicated that a single major transcript of about 6.4 kb was generated from the dicistronic construct espCP-RDRP:GFP and that this transcript hybridized with all three probes, indicating that RDRP was expressed from the full-length dicistronic mRNA and not from a shorter transcript (a subgenomic mRNA) (Fig. 4, lanes espCP-RDRP:GFP). The transcript produced from the construct espCP-RDRP:GFPt had a predicted size of 4.5 kb and hybridized with the CP and GFP probes (Fig. 4, lanes espCP-RDRP:GFPt). No hybridization was detected with the RDRP probe (nt 3735 to 4917) because the transcript contains only RDRP-derived sequence from nt 2605 to 2684. The transcript obtained from expression of espCP:GFP has a predicted size of approximately 4.7 kb and hybridized with both the CP and GFP probes; no hybridization signals were detected with the RDRP probe (Fig. 4, lanes espCP:GFP). As expected, the full-length Hv190SV transcript (5.2 kb) hybridized with both the CP and RDRP sequence-specific probes, but not with the GFP probe (Fig. 4, lanes PT7190SV-transcript).

FIG. 4.

Northern analysis of transcripts generated in S. pombe expressing the Hv190SV CP and RDRP ORFs. Blots containing total RNA isolated from transformed S. pombe at 18 h postinduction were hybridized with [α-32P]dCTP-random-primed probes generated from restriction fragments containing the CP and GFP ORFs and a PCR-amplified product corresponding to nt 3735 to 4917 of the RDRP ORF. The in vitro T7 RNA polymerase-synthesized transcript (approximately 5.2 kb) from a full-length cDNA clone of Hv190SV dsRNA (lanes PT7190SV-transcript), which hybridized to both CP and RDRP probes, was included for comparison. Single major transcripts of the predicted sizes (approximately 4.7, 4.5, and 6.4 kb) were generated following the expression of espCP:GFP, espCP-RDRP:GFPt, and espCP-RDRP:GFP, respectively.

Totiviruses that infect filamentous fungi express their RDRP independently from CP.

The data presented in this study and previously (9) indicate that Hv190SV is distinct from other totiviruses in that it expresses its RDRP as a separate nonfused polypeptide rather than a CP-RDRP fusion protein. Convincing evidence has been presented that the totiviruses infecting yeast and the protozoa G. lamblia and T. vaginalis express their RDRP only as a CP-RDRP fusion via −1 (or +1) ribosomal frameshifting and that the CP-RDRP fusion protein is detectable as a virion-associated minor protein (12, 17, 21, 28). Although Gag-Pol-like fusion proteins have not been detected in Leishmania brasiliensis infected with the totivirus LRV1, the presence of both a slippery site and a predicted pseudoknot structure in the overlap region supports the notion that RDRP is expressed via a +1 translational frameshift (25). The recent report that two totiviruses (SsRV1 and SsRV2) infecting the filamentous fungus Sphaeropsis sapinea are similar to Hv190SV in genome organization and predicted expression strategy is of considerable interest (22). Like Hv190SV, SsRV1 and SsRV2 have a short overlapping region between the two ORFs that lacks both a slippery site and a predicted pseudoknot. Likewise, these two viruses may not synthesize CP-RDRP fusion proteins. The totiviruses that infect filamentous fungi thus appear to represent a distinct group of totiviruses that share the feature of expressing RDRP as a nonfused separate protein. In this regard, these totiviruses resemble the foamy viruses, a subgroup of retroviruses that break the general rule of expression of the pol gene as a Gag-Pol fusion (3).

The mechanism of expression of Hv190SV RDRP and how the level of expression is regulated are important questions that will be addressed in future studies. The Gag-independent expression of the foamy virus Pol protein, mentioned above, has been demonstrated to involve a spliced pol mRNA (13). There is no evidence, however, that Hv190SV RDRP is expressed from a transcript (subgenomic RNA) shorter than the full-length dicistronic mRNA. No transcript of 2.3 or 2.4 kb was detected by Northern hybridization in lysates of RDRP-expressing S. pombe cells transformed with the dicistronic CP-RDRP constructs (Fig. 4). Furthermore, no in vitro transcripts that can be translated to produce RDRP were generated in in vitro transcription reactions with purified Hv190SV virions (6). The majority of transcripts that were produced in such reactions were full-length single-stranded RNA transcripts (5.2 kb) that directed the synthesis of the CP polypeptide p88 (6). A report on generating a short transcript via site-specific cleavage within the 5′ UTR of the full-length mRNA of the totivirus LRV1 is of interest in this regard (19). Several viral and eukaryotic host RNA polymerases are known to possess polymerase-associated endonuclease activities (14).

Expression of the downstream RDRP ORF from the Hv190SV dicistronic genome may occur by one of three mechanisms: leaky scanning, internal ribosome entry, and coupled termination-reinitiation of translation. A combination of more than one mechanism may be involved in the expression of such internal ORFs in eukaryotes (11). The fact that the initiation codon (ACAAUGA) of the downstream RDRP cistron on the Hv190SV dicistronic genome is in a more favorable context than the initiator AUG codon (UCCAUGU) of the upstream CP ORF may support the idea that translation of RDRP occurs by leaky scanning. This, however, seems unlikely because of the very long distance (2,316 nt) separating the two start codons and the presence of several AUGs in an optimal context (AXXAUGG) within the CP ORF upstream of the RDRP cistron. The distance between the initiation codons of overlapping cistrons, as deduced from well-documented examples of translations by leaky scanning, is usually less than 150 nt, and in no case is it longer than 900 nt (4, 8, 23). Furthermore, the structural features of the 5′ UTR of Hv190SV positive-sense RNA (including its secondary structure and the presence of two minicistrons with AUGs in favorable contexts) predict that the upstream CP ORF (with its AUG present in a suboptimal context) is translated via an internal ribosome entry mechanism (9). It is of interest that for the two known examples for overlapping start and stop codons of the type AUGA (where the initiator AUG codon of the downstream cistron overlaps the UGA stop codon of the upstream ORF), expression of the downstream ORF occurs by leaky scanning (4, 8). Those two virus systems (Rice tungro bacilliform virus and Peanut clump virus RNA-2), unlike Hv190SV (whose two ORFs also exhibit the AUGA overlapping feature), contain no AUG codons within the sequence separating the upstream and downstream initiation codons.

It is also unlikely that the downstream RDRP ORF of Hv190SV is expressed via IRES-mediated internal initiation since present evidence suggests that the upstream CP ORF is expressed by such a mechanism, as discussed earlier. As far as we know there are no examples of dicistronic viral genomes whose two overlapping ORFs are both expressed by an internal ribosome binding mechanism. The molar ratio of RDRP in the virions is about 1 to 2%, and the efficiency of RDRP expression in infected cells relative to that of CP is expected to be similarly low. Such very low levels of expression could conceivably be attained via a coupled termination-reinitiation mechanism. The efficiency of reinitiation on viral and eukaryotic dicistronic mRNAs has been reported to be inversely related to the size of the upstream ORF and positively correlated with the length of the intercistronic region (11, 15, 16, 18). The facts that the upstream CP ORF is relatively long (2,319 nt) and that the CP and RDRP ORFs have overlapping stop and start codons of the AUGA type may explain the low frequency of reinitiation and RDRP expression. The finding that RDRP is expressed from its downstream ORF in dicistronic constructs in a heterologous eukaryotic system (S. pombe), but not in bacteria, suggests that a eukaryotic host factor(s) is required for regulating reinitiation of translation and expression of RDRP. The S. pombe expression system should provide, in future studies, valuable information on viral sequences and host factors required for expression of the RDRP ORF.

In conclusion, we demonstrated the expression in S. pombe cells of the downstream RDRP ORF of Hv190SV from dicistronic constructs. Unlike the RDRPs of some other totiviruses, which are expressed as CP-RDRP fusion proteins, Hv190SV RDRP was detected only as a separate nonfused polypeptide. We found no evidence that RDRP is translated from a transcript shorter than the full-length dicistronic mRNA. Based on the known structural features of the genome of Hv190SV, we proposed that coupled termination-reinitiation of translation is the most likely mechanism for expression of RDRP. We explained the low efficiency of RDRP expression on the tight arrangement of the intercistronic region between the CP and RDRP ORFs featuring the AUGA-type overlap between the start and stop codons of the two ORFs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wendy Havens for technical support.

This work was supported by a grant from the USDA NRI Competitive Grants Program (agreement no. 96-35303-3240).

Footnotes

Publication no. 99-12-92 of the Kentucky Agricultural Experiment Station.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dinman J D, Icho T, Wickner R B. A −1 ribosomal frameshift in a double-stranded RNA virus of yeast forms a gag-pol fusion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:174–178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.1.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enssle J, Jordan I, Mauer B, Rethwilm A. Foamy virus reverse transcriptase is expressed independently from the Gag protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4137–4141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fütterer J, Rothnie H M, Hohn T, Potrykus I. Rice tungro bacilliform virus open reading frames II and III are translated from polycistronic pregenomic RNA by leaky scanning. J Virol. 1997;71:7984–7989. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7984-7989.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghabrial S A. New developments in fungal virology. Adv Virus Res. 1994;43:303–388. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60052-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghabrial S A, Havens W M. Conservative transcription of Helminthosporium victoriae 190S virus double-stranded RNA in vitro. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:1025–1035. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghabrial S A, Bruenn J A, Buck K W, Wickner R B, Patterson J L, Stuart K D, Wang A L, Wang C C. Totiviridae. In: Murphy F A, Fauquet C M, Bishop D H L, Ghabrial S A, Jarvis A W, Martelli G P, Mayo M A, Summers M D, editors. Virus taxonomy. Sixth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1995. pp. 245–252. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herzog E, Guilley H, Fritsch C. Translation of the second gene of peanut clump virus RNA 2 occurs by leaky scanning in vitro. Virology. 1995;208:215–225. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang S, Ghabrial S A. Organization and expression of the double-stranded RNA genome of Helminthosporium victoriae 190S virus, a totivirus infecting a plant pathogenic filamentous fungus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12541–12546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang S, Soldevila A I, Webb B A, Ghabrial S A. Expression, assembly, and proteolytic processing of Helminthosporium victoriae 190S totivirus capsid protein in insect cells. Virology. 1997;234:130–137. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang W-L, Su T-S. Translational regulation of hepatitis B virus polymerase gene by termination-reinitiation of an upstream minicistron in a length-dependent manner. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:2181–2189. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-9-2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Icho T, Wickner R B. The double-stranded RNA genome of yeast virus L-A encodes its own putative RNA polymerase by fusing two open reading frames. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:6716–6723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jordan I, Enssle J, Güttler E, Mauer B, Rethwilm A. Expression of human foamy virus reverse transcriptase involves a spliced pol mRNA. Virology. 1996;224:314–319. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kassavetis G A, Geiduschek E P. RNA polymerase marching backward. Science. 1993;259:944–945. doi: 10.1126/science.7679800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kozak M. Effects of intercistronic length on the efficiency of reinitiation by eucaryotic ribosomes. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:3438–3445. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.10.3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kozak M. The scanning model for translation: an update. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:229–235. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.2.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu H-W, Chu Y D, Tai J-H. Characterization of Trichomonas vaginalis virus proteins in the pathogenic protozoan T. vaginalis. Arch Virol. 1998;143:963–970. doi: 10.1007/s007050050345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luukkonen B G M, Tan W, Schwartz S. Efficiency of reinitiation of translation on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mRNA is determined by the length of the upstream open reading frame and by intercistronic distance. J Virol. 1995;69:4086–4094. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4086-4094.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacBeth K J, Patterson J L. The short transcript of Leishmania RNA virus is generated by RNA cleavage. J Virol. 1995;69:3458–3464. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3458-3464.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maga J A, Widmer G, LeBowitz J H. Leishmania RNA virus 1-mediated cap-independent translation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4884–4889. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.9.4884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park C-M, Lopinski J D, Masuda J, Tzeng T-H, Bruenn J A. A second double-stranded RNA virus from yeast. Virology. 1996;216:451–454. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Preisig O, Wingfield B D, Wingfield M J. Coinfection of a fungal pathogen by two distinct double-stranded RNA viruses. Virology. 1998;252:399–406. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sivakumaran K, Hacker D L. The 105-kDa polyprotein of Southern bean mosaic virus is translated by scanning ribosomes. Virology. 1998;246:34–44. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soldevila A I, Huang S, Ghabrial S A. Assembly of the Hv190S totivirus capsid is independent of posttranslational modification of the capsid protein. Virology. 1998;251:327–333. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stuart K D, Weeks R, Guilbride L, Myler P J. Molecular organization of the Leishmania RNA virus LRV1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8596–8600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsien R Y. The green fluorescent protein. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:509–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tzeng T-H, Tu C-L, Bruenn J A. Ribosomal frameshifting requires a pseudoknot in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae double-stranded RNA virus. J Virol. 1992;66:999–1006. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.999-1006.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang A L, Yang H-M, Shen K A, Wang C C. Giardiavirus double-stranded RNA genome encodes a capsid polypeptide and a gag-pol-like fusion protein by a translation frameshift. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8595–8599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]