Abstract

Purpose

To explore the potential of quantitative parameters of the hydrogel spacer distribution as predictors for separating the rectum from the planning target volume (PTV) in linear‐accelerator‐based stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for prostate cancer.

Methods

Fifty‐five patients underwent insertion of a hydrogel spacer and were divided into groups 1 and 2 of the PTV separated from and overlapping with the rectum, respectively. Prescribed doses of 36.25–45 Gy in five fractions were delivered to the PTV. The spacer cover ratio (SCR) and hydrogel–implant quality score (HIQS) were calculated.

Results

Dosimetric and quantitative parameters of the hydrogel spacer distribution were compared between the two groups. For PTV, D 99% in group 1 (n = 29) was significantly higher than that in group 2 (n = 26), and D max, D 0.03cc, D 1cc, and D 10% for the rectum were significantly lower in group 1 than in group 2. The SCR for prostate (89.5 ± 12.2%) in group 1 was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than that in group 2 (74.7 ± 10.3%). In contrast, the HIQS values did not show a significant difference between the groups. An area under the curve of 0.822 (95% confidence interval, 0.708–0.936) for the SCR was obtained with a cutoff of 93.6%, sensitivity of 62.1%, and specificity of 100%.

Conclusions

The SCR seems promising to predict the separation of the rectum from the PTV in linear‐accelerator‐based SBRT for prostate cancer.

Keywords: dose, hydrogel spacer, prostate, SBRT

1. INTRODUCTION

Developments in radiotherapy, such as intensity‐modulated and volumetric modulated arc therapies, have reduced the gastrointestinal and genitourinary toxicity rates in patients with prostate cancer compared with previous techniques, 1 and their results can be comparable to those of prostatectomy. 2 Recently, the α/β value of prostate cancer (1.5−1.8 Gy) has been found to be lower than that of a risk organ such as the rectum (3−5 Gy), 3 , 4 indicating the radiobiological advantages of hypofractionated radiotherapy over conventional fractionated radiotherapy. In addition, since the COVID‐19 (coronavirus disease) pandemic, the demand for fewer irradiations has increased. 5 These circumstances have led to the rapid implementation in clinical practice of ultrahypofractionated stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), which delivers a high radiation dose in a small fraction.

SBRT provides failure‐free survival comparable to that of conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for intermediate‐to‐high‐risk prostate cancer, 6 and the treatment approach seems to improve the efficacy and patient quality of life by reducing the frequency of medical visits. However, SBRT may cause early side effects of radiation. Insertion of a hydrogel spacer can physically separate the rectum from the prostate, drastically reducing the radiation dose to the rectum. 7 Ogita et al. demonstrated that using a hydrogel spacer provided the dosimetric benefits of reduced rectal doses and improved patient‐reported acute bowel toxicity. 8 Similarly, Kundu et al. reported that using a hydrogel spacer reduced the rectal radiation dose and that the incidence of acute gastrointestinal injury in the group with hydrogel spacer was significantly lower than that without spacer. 9

Although trained physicians insert hydrogel spacers, variabilities in both the separation between the prostate and rectum and hydrogel spacer distribution are observed. Fischer‐Valuck et al. demonstrated that the asymmetrical distribution of hydrogel spacers for three axial images (midgland axial slice, 1 cm superior to midgland, and 1 cm inferior to midgland) was significantly related to the rectal dose in conventional fractionated radiotherapy. 10 Hwang et al. demonstrated that the hydrogel volume and angle θ formed by the prostate, hydrogel, and rectum correlated with dosimetric parameters of the rectum. 11 The assessment of hydrogel spacer distribution can contribute to appropriate insertion, but no established method has been devised to that end. Liu et al. derived the hydrogel‐implant quality score (HIQS) related to the rectal dose in low‐dose‐rate brachytherapy, and the HIQS score could account for various aspects of the hydrogel spacer distribution including hydrogel spacer volume, left‐right (LR) symmetry, superior‐inferior (SI) symmetry, and mid‐prostate spacing created by hydrogel spacer. 12 Although the method proposed by Liu et al. is considered reasonable because it takes into account the shape of the entire hydrogel spacer distribution, there are no studies of its application to linear‐accelerator‐based SBRT for prostate cancer. In clinical practice, a more simplified method of evaluating hydrogel spacer distribution is required. The primary purpose of inserting a hydrogel spacer is separating the rectum from the irradiated volume, that is, the planning target volume (PTV) in linear‐accelerator‐based SBRT. We hypothesized that it would be important to simply distribute hydrogel spacer widely in the SI direction to prevent PTV and rectum from overlapping.

This study was aimed to compare dosimetric parameters between two groups, namely, group 1 with the PTV separated from the rectum and group 2 with the PTV overlapping with the rectum. Second, the HIQS was evaluated for distinguishing between these two groups. Finally, it was intended to explore the potential of simplified quantitative parameters of hydrogel spacer distribution as predictors for separating the rectum from the PTV in linear‐accelerator‐based SBRT for prostate cancer.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Patients and simulation

This retrospective study included 55 patients with prostate cancer who underwent SBRT with or without androgen deprivation therapy. The study design and protocols were approved by the corresponding institutional review board. A hydrogel spacer (SpaceOAR system; Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA) was inserted into the perirectal space between the prostate and rectum under transrectal ultrasound guidance. 8 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed approximately 1 week after hydrogel spacer placement. For computed tomography (CT) simulation, patients were scanned in the supine position, and CT images were reconstructed with a slice thickness of 1 mm. In preparation for MRI and CT acquisitions, the patients were instructed to maintain a full bladder and had the rectum emptied by receiving an enema.

2.2. Treatment planning

Based on MRI/CT fusion, the target organs at risk (OARs) and hydrogel spacer were delineated by radiation oncologists. The clinical target volume (CTV) for intermediate‐/high‐risk patients comprised the prostate and proximal 10/2 cm of the seminal vesicles (SVs) according to the risk classification of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines version 2.2021. 8 The PTV was generated by adding a margin of 3 mm in the posterior direction and 5 mm in any other direction. The Monaco treatment planning system (Elekta AB, Stockholm, Sweden) was used to deliver 36.25−45 Gy in five fractions to 95% volume of the PTV every alternate weekday. For treatment planning, a multileaf collimator of 5 mm, photon beam energy of 6 MV (flattening filter free), dose calculation using the Monte Carlo method with 1% statistical uncertainty, and dose calculation grid of 2 mm were used. Dose constraints were set for the rectum, bladder, femoral head, small bowel, sigmoid colon, and penile bulb to reduce the radiation doses as much as possible. In cases where the small bowel and PTV overlapped, the radiation oncologist cut the PTV.

2.3. Assessment of hydrogel spacer distribution

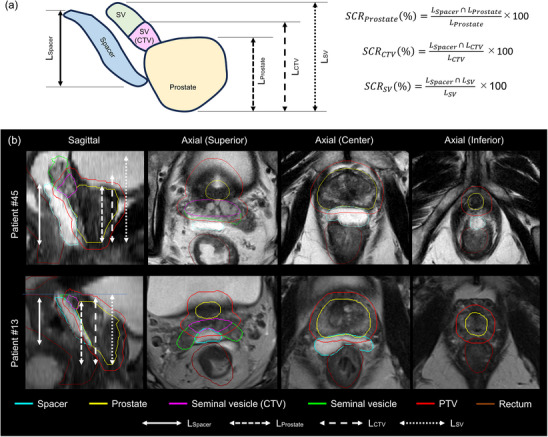

For each patient, the thickness of the hydrogel spacer was manually measured in the axial image at the prostate center, 10 and 20 mm superior to the prostate center (S 10mm and S 20mm, respectively), and 10 and 20 mm inferior to the prostate center (I 10mm and I 20mm, respectively). In each axial image, the thickness of the hydrogel spacer was measured at five points: prostate center, 5 and 10 mm to the left of the center (L 5mm and L 10mm, respectively), and 5 and 10 mm to the right of the center (R 5mm and R 10mm, respectively). The lengths of the hydrogel spacer (L Spacer), prostate (L Prostate), CTV (L CTV), and prostate plus SV (L SV) were determined as the distances in the SI direction of the corresponding target volumes (Figure 1a). The spacer cover ratios (SCRs, in percentages) for the prostate (SCR Prostate), CTV (SCR CTV), and prostate plus SV (SCR SV) were calculated by dividing the overlapping length of L Spacer and L Prostate as well as L CTV and L SV by L Prostate, L CTV, and L SV and multiplying by 100, respectively.

FIGURE 1.

(a) Calculation of SCR for prostate (SCR Prostate), CTV (SCR CTV), and prostate plus SV (SCR SV). (b) Distribution of hydrogel spacer for patients 45 (group 1; SCR Prostate, SCR CTV, and SCR SV of 100%, 90.6%, and 66.9%, respectively) and 13 (group 2; SCR Prostate, SCR CTV, and SCR SV of 67.3%, 66.7%, and 62.8%, respectively).

The HIQS was calculated as in the method proposed by Liu et al. 12 The scores for the inserted hydrogel volume (HIQS Vol), left–right symmetry (HIQS LR), SI symmetry (HIQS SI), and mid‐prostate spacing created by the hydrogel (HIQS Spacing) were calculated as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where V Spacer is the volume of inserted hydrogel spacer, V Left, V Right, V Superior, and V Inferior are the volumes of the hydrogel space divided by the prostate center, and D center is the distance between the prostate and rectum achieved by the hydrogel spacer insertion measured at the center of the prostate. The total HIQS (HIQS total) was obtained as

| (5) |

2.4. Data analysis

Because the prescribed dose varied depending on the patient, dosimetric parameters for the PTV, rectum, and bladder were evaluated by the relative dose. For the PTV, we obtained dosimetric parameters (in percentages) D max, D 1%, D 50%, D 99%, and D min, which indicate the maximum dose, doses to 1%, 50%, and 99% target volume, and minimum dose, respectively. For the rectum and bladder, D max, D 0.03cc (dose to 0.03 cc of OAR volume), D 1cc (dose to 1 cc of OAR volume), D 10% (dose to 10% OAR volume), D 20% (dose to 20% OAR volume), and D 50% (dose to 50% OAR volume) were evaluated. 13

The patients were divided into two groups. In group 1, the PTV was separated from the rectum, and in group 2, the PTV overlapped with the rectum. The Mann–Whitney U, Fisher, or Pearson's chi‐squared test was applied to measure significant differences in patient characteristics, volumes (prostate, SV, CTV, PTV, rectum, and bladder), dosimetric parameters for the target and OARs, thickness of the hydrogel spacer measured at various positions, and values of the hydrogel spacer distribution (i.e., SCR and HIQS) between groups 1 and 2. Value p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. For parameters with significant differences, the optimal cutoff value for distinguishing between the two groups was determined through receiver operating characteristic analysis. The sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve (AUC) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Finally, the relationship between the value with the highest AUC and dosimetric parameters for the rectum was tested using Pearson's correlation coefficient. Pearson's r was categorized into very weak (0–0.19), weak (0.2–0.39), moderate (0.40–0.59), strong (0.6–0.79), and very strong (0.8–1). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 27; IBM, Armonk, NY).

3. RESULTS

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 29 and 26 patients in groups 1 and 2, respectively. The patient characteristics did not show a significant difference (p > 0.05) (Table 1) as well as the volumes of prostate, SV, CTV, PTV, rectum, and bladder between the two groups (Table 2). Table 3 lists the dosimetric parameters for the targets and OARs in the two groups. For the PTV, comparable D max, D 1%, D 50%, and D min were obtained between the groups, while D 99% in group 1 (97.4 ± 0.6%) was significantly higher (p = 0.038) than that in group 2 (96.9 ± 0.8%). For the rectum, D max (84.3 ± 10.6%), D 0.03cc (78.7 ± 11.7%), D 1cc (60.3 ± 12.1%), and D 10% (43.7 ± 9.7%) were significantly lower (p < 0.05) for group 1 than for group 2 (98.0 ± 4.2%, 94.6 ± 5.1%, 75.3 ± 10.1%, and 51.7 ± 10.1% for D max, D 0.03cc, D 1cc, and D 10%, respectively). There were no significant differences in the dosimetric parameters of the bladder (p > 0.05).

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristics | Group 1 (n = 29) |

Group 2 (n = 26) |

p‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y), median (range) | 69 (60–84) | 73 (59–85) | 0.133 |

| Risk (n) | |||

| Intermediate (favorable) | 8 | 10 | 0.690 |

| Intermediate (unfavorable) | 16 | 12 | |

| High or Ultra‐high | 5 | 4 | |

| T stage (n) | 0.202 | ||

| T1 | 2 | 1 | |

| T2 | 25 | 25 | |

| T3 | 2 | 0 | |

| Gleason Score (n) | 0.556 | ||

| 3+4 | 25 | 22 | |

| 4+4 | 3 | 4 | |

| 5+5 | 1 | 0 | |

| PSA (n) | 0.389 | ||

| <10 | 19 | 20 | |

| 10≤ | 10 | 6 | |

| Androgen deprivation therapy (n) | 1.000 | ||

| Yes | 20 | 17 | |

| No | 9 | 9 | |

| History of Intrapelvic Surgery (n) | 1.000 | ||

| Yes | 3 | 2 | |

| No | 26 | 24 | |

| History of pelvic irradiation (n) | NA | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | |

| No | 29 | 26 |

TABLE 2.

Comparison of structure volumes.

| Group 1 (n = 29) | Group 2 (n = 26) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume (cm3) | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p‐value |

| Prostate | 27.6 | 10.1 | 29.9 | 10.9 | 0.555 |

| Seminal vesicle | 12.4 | 7.4 | 12.3 | 6.4 | 0.840 |

| CTV | 32.3 | 10.4 | 34.6 | 12.0 | 0.686 |

| PTV | 70.8 | 16.3 | 75.6 | 19.9 | 0.590 |

| Rectum | 45.0 | 15.0 | 46.2 | 10.8 | 0.418 |

| Bladder | 250.8 | 80.5 | 335.0 | 154.3 | 0.071 |

TABLE 3.

Comparison of dosimetric parameters for PTV and OARs in the two groups; group 1 with the PTV separated from the rectum and group 2 with the PTV overlapping with the rectum.

| Group 1 (n = 29) | Group 2 (n = 26) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dosimetric parameter (%) | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p‐value | |

| PTV | D max | 109.8 | 1.7 | 109.2 | 1.5 | 0.500 |

| D 1% | 106.3 | 0.9 | 106.1 | 0.9 | 0.544 | |

| D 50% | 102.9 | 0.4 | 102.9 | 0.5 | 0.893 | |

| * D 99% | 97.4 | 0.6 | 96.9 | 0.8 | 0.038 | |

| D min | 88.7 | 3.2 | 86.3 | 4.6 | 0.059 | |

| Rectum | * D max | 84.3 | 10.6 | 98.0 | 4.2 | <0.001 |

| * D 0.03cc | 78.7 | 11.7 | 94.6 | 5.1 | <0.001 | |

| * D 1cc | 60.3 | 12.1 | 75.3 | 10.1 | <0.001 | |

| * D 10% | 43.7 | 9.7 | 51.7 | 10.1 | 0.014 | |

| D 20% | 34.4 | 8.2 | 38.9 | 8.1 | 0.089 | |

| D 50% | 22.2 | 6.5 | 23.0 | 5.4 | 0.438 | |

| Bladder | D max | 107.0 | 1.0 | 107.1 | 0.8 | 0.527 |

| D 0.03cc | 105.8 | 0.8 | 105.8 | 0.7 | 0.595 | |

| D 1cc | 103.9 | 0.7 | 104.1 | 0.6 | 0.200 | |

| D 10% | 72.6 | 12.9 | 69.5 | 15.4 | 0.601 | |

| D 20% | 47.0 | 15.0 | 43.8 | 16.3 | 0.827 | |

| D 50% | 13.6 | 11.3 | 11.1 | 7.3 | 0.787 | |

p < 0.05.

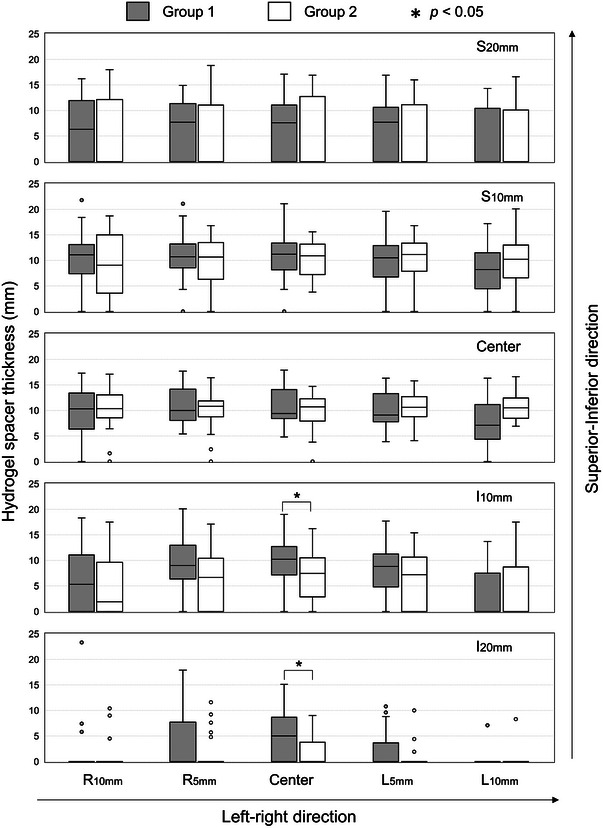

Figure 2 shows the measured hydrogel spacer thicknesses at various points. The spacer thickness was the highest at the prostate center (1.1 ± 0.4 mm and 1.0 ± 0.4 mm in groups 1 and 2, respectively) and reduced as the spacer moved away in the SI and LR directions. The hydrogel spacer on the inferior side was thinner than that on the superior side. A significant difference in thickness (p < 0.05) was observed in the prostate center in I 10mm (0.9 ± 0.5 mm and 0.6 ± 0.5 mm in groups 1 and 2, respectively) and I 20mm (0.5 ± 0.5 mm and 0.2 ± 0.3 mm in groups 1 and 2, respectively).

FIGURE 2.

Measured thicknesses of hydrogel spacer at various points.

Figure 1b shows the distribution of hydrogel spacer for patients 45 (group 1; SCR Prostate, SCR CTV, and SCR SV of 100%, 90.6%, and 66.9%, respectively) and 13 (group 2; SCR Prostate, SCR CTV and SCR SV of 67.3%, 66.7%, and 62.8%, respectively). Table 4 lists the values of hydrogel spacer distribution between the two groups. In both groups, equivalent volumes of hydrogel spacer were inserted (11.4 ± 3.0 cc and 11.2 ± 2.8 cc in groups 1 and 2, respectively; p = 0.505). SCR Prostate (89.5 ± 12.2%), SCR CTV (86.1 ± 11.7%), and SCR SV (76.1 ± 11.9%) in group 1 were significantly higher (p < 0.05) than those in group 2 (74.7 ± 10.3%, 72.5 ± 9.8%, and 65.4 ± 11.8% for SCR Prostate, SCR CTV, SCR SV, respectively). In contrast, the HIQS values (HIQS Vol, HIQS LR, HIQS SI, HIQS Spacing, and HIQS total) did not provide significant differences between the two groups (p > 0.05). Table 5 lists the cutoff values, sensitivities, specificities, and AUCs for distinguishing between the two groups. The highest sensitivity of 89.7% was obtained at 64.4% cutoff for SCR SV. Overall, the AUC (0.822; 95% CI, 0.708–0.936) was the highest for SCR Prostate at 93.6% cutoff, 62.1% sensitivity, and 100% specificity.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of quantitative values of hydrogel spacer distribution between two groups.

| Group 1 (n = 29) | Group 2 (n = 26) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative value | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p‐value |

| Spacer volume (cc) | 11.4 | 3.0 | 11.2 | 2.8 | 0.505 |

| * SCRProstate (%) | 89.5 | 12.2 | 74.7 | 10.3 | <0.001 |

| * SCRCTV (%) | 86.1 | 11.7 | 72.5 | 9.8 | <0.001 |

| * SCRSV (%) | 76.1 | 11.9 | 65.4 | 11.8 | 0.003 |

| HIQSVol | 17.2 | 4.8 | 17.0 | 4.5 | 0.565 |

| HIQSLR | 19.9 | 4.2 | 19.7 | 5.1 | 0.819 |

| HIQSSI | 15.6 | 5.7 | 13.9 | 6.8 | 0.299 |

| HIQSSpacing | 14.5 | 5.1 | 13.4 | 4.8 | 0.774 |

| HIQStotal | 67.3 | 12.1 | 64.1 | 12.2 | 0.453 |

p < 0.05.

TABLE 5.

Cutoff values, sensitivities, specificities, and AUCs for distinguishing between the two groups derived from receiver operating characteristic analysis.

| Parameter | Cutoff value (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | AUC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCRProstate | 93.6 | 62.1 | 100.0 | 0.822 (0.708–0.936) |

| SCRCTV | 77.8 | 75.9 | 76.9 | 0.807 (0.690–0.924) |

| SCRSV | 64.4 | 89.7 | 57.7 | 0.737 (0.602–0.873) |

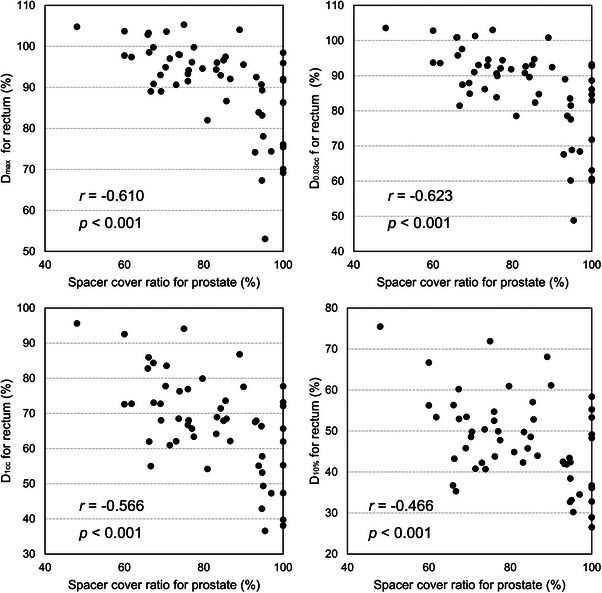

Figure 3 shows the relationship between SCR Prostate and the dosimetric parameters for the rectum. A significantly strong correlation was observed between SCR Prostate and D max (r = 0.610, p < 0.001) and D 0.03cc (r = 0.623, p < 0.001). In other words, a higher SCR Prostate indicates a reduced high‐dose radiation to the rectum.

FIGURE 3.

Relationship between SCR and dosimetric parameters for prostate.

4. DISCUSSION

We explored quantitative parameters of hydrogel spacer distributions to separate the rectal volume from the PTV in linear‐accelerator‐based SBRT for prostate cancer. In conventional fractionated radiotherapy for prostate cancer (prescribed dose of 70−79.2 Gy), using a hydrogel spacer is rare, thus resulting in overlapping PTV and rectum. Fiorino et al. reported that dosimetric parameter V 70Gy (i.e., relative volume receiving 70 Gy) for the rectum should remain in 25%−30% to maintain the incidence of moderate/severe rectal bleeding below 5%−10%. 14 Therefore, treatment plans should reduce the high‐dose region of the rectum within the PTV, being inconsistent with guaranteeing an adequate dose to the PTV. In SBRT, the rectum is strictly constrained to minimize rectal toxicity. The dose constraint for the rectum was set as D max of 38 Gy with a prescribed dose of 38 Gy in four fractions at the University of North Carolina (NCT 00643617). Wang et al. stated that toxicity may be reduced by limiting D max for the rectum to the prescribed dose. 13 To maintain D max for the rectum below the prescribed dose without compromising the dose delivered to the PTV, the rectum should be physically separated from the PTV using a hydrogel spacer.

A hydrogel spacer is inserted into the rectoprostatic space, and its material remains stable in size for several months until its absorption. Wang et al. proposed a method to predict rectal dose from the anatomical shape of the rectum and PTV. 15 Paetkau et al. found that the volumes of rectum in PTV as well as CTV and rectum volumes offered highest correlation with rectal doses. 16 Characterizing the quality of the hydrogel spacer distribution is an active research area. Grossman et al. proposed a spacer quality score for the prostate‐rectal interspace in a range from 0 to 2 based on the thickness of the hydrogel spacer at various points, and they found that the score was significantly associated with dosimetric parameters D max and D 1cc for the rectum. 17 The HIQS was developed by Liu et al. 12 as an innovative indicator that quantifies the distribution of spacers and it might provide insights into physicians learning and dosimetric outcome. However, a correlation between the HIQS and overlapping between the PTV and rectum was not determined in linear accelerator based SBRT for prostate cancer. As the HIQS was originally intended for low‐dose‐rate brachytherapy, it may not have been significantly correlated with the studied dose distribution of volumetric modulated arc therapy. Such quantitative measurements of hydrogel spacer distribution are labor intensive in clinical practice and may hinder goal achievement to physicians who insert spacers. Hwang et al. demonstrated that patients with the lower Dmax of rectum and larger values of angle θ formed by the prostate, hydrogel, and rectum multiplied by hydrogel spacer volume did not show the rectal toxicity. 11 Because our proposed simplified SCR Prostate is associated with higher doses to the rectum, it may be a useful indicator in predicting rectal toxicity in clinical practices.

The insertion of spacers with uniform thickness is not easy in clinical practice. The spacer thickness decreased with increasing distance from the prostate center, and this trend was greater in the inferior than in the superior direction (Figure 2). Eckert et al. reported similar results, with the distance between the prostate and rectum after hydrogel spacer insertion being larger in the middle and base (superior direction) of the prostate than in the apex (inferior direction). 18 Whalley et al. observed the area of radiation proctitis at the prostatic apex level in one patient, and the hydrogel spacer provided adequate separation except for the apex region. 19 Our suggested parameter SCR Prostate, which represents the hydrogel spacer distribution, was significantly correlated with the dosimetric parameters for the rectum (Figure 3) and may be a simple indicator for physicians. In this study, if more than 93.6% of the prostate posterior could be covered by hydrogel spacer, there was no overlap between PTV and rectum in all cases (Table 5). Therefore, when inserting hydrogel spacer, care should be taken to ensure that the apex region is also adequately covered. In general, a needle tip is placed at the center of the prostate, and the hydrogel spacer is then injected. Fukumitsu et al. presented a hydrogel injection technique, in which the needle was placed at a level corresponding to a ratio base: apex side of 6:4, and separation was observed at all levels from the base to the apex of the prostate. 20 Insufficient separation of the rectum and prostate may result in high‐dose irradiation to the rectum. Thus, the entire prostate, from its base to apex, must be covered with a hydrogel spacer.

This study has various limitations. First, the number of patients was small, possibly affecting the statistical calculations. Second, a wider distribution of spacers on the SI direction was more effective in reducing rectal dose than a thicker insertion of spacers.at a given point when using a CTV‐to‐PTV margin of 3 mm in the posterior direction was adopted, but the results may vary depending on the posterior margin size. Studenski et al. demonstrated that a posterior margin of 3 mm in prostate SBRT allowed to maintain prostate coverage while compromising the PTV coverage. 21 Third, inter‐observer variability occurred in prostate and spacer contouring, possibly affecting our results. Fourth, the relationship between SCR Prostate and rectal toxicity could not be investigated, and further studies are needed to determine whether SCR Prostate can be used to predict rectal toxicity. Because of inter‐ and intra‐fractional motion of prostate and rectum during actual treatment, the rectal dose may differ between treatment planning and treatment. It might be necessary to develop an alternative index to SCR Prostate that is less sensitive to inter‐ and intra‐fractional motion. Finally, the Barrigel hydrogel spacer (Palette Life Sciences, Stockholm, Sweden), which can take time to sculpt from the base to apex because of the lacking polymerization, 22 , 23 and SpaceOAR Vue (Boston Scientific), which consists of a hydrogel covalently bonded with iodine to improve visibility in CT images, 24 are also available. The difficulty in inserting a hydrogel spacer in the proper position may vary depending on the type of hydrogel spacer, but this was not assessed in our study.

In conclusion, the separation between the PTV and rectum is a significant indicator for reducing rectal dose in SBRT for prostate cancer. The hydrogel spacer is significantly thinner in the inferior direction (apex) in group 2 (overlapping PTV and rectum) than in group 1 (without overlapping). SCR Prostate seems to be an adequate indicator for distinguishing between the two groups and may assist physicians in the appropriate insertion of a hydrogel spacer.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors participated in the writing of this article and are responsible for its content. The authors declare that the contents of this manuscript have neither been published nor submitted for publication elsewhere.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Shingo Ohira, Masanari Minamitani, and Keiichi Nakagawa belong, is an endowment department, supported with an unrestricted grant from Elekta K. K. However, the sponsor had no role in this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a JSPS KAKENHI Grant (Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research (C) 21K07742).

Ohira S, Yamashita H, Minamitani M, et al. Relationship between hydrogel spacer distribution and dosimetric parameters in linear‐accelerator‐based stereotactic body radiotherapy for prostate cancer. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2024;25:e14294. 10.1002/acm2.14294

REFERENCES

- 1. Michalski JM, Yan Y, Watkins‐Bruner D, et al. Preliminary toxicity analysis of 3‐dimensional conformal radiation therapy versus intensity modulated radiation therapy on the high‐dose arm of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 0126 prostate cancer trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;87(5):932‐938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guo XX, Xia HR, Hou HM, et al. Comparison of oncological outcomes between radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy by type of radiotherapy in elderly prostate cancer patients. Front Oncol. 2021;11:708373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dasu A, Toma‐Dasu I. Prostate alpha/beta revisited—an analysis of clinical results from 14 168 patients. Acta Oncol. 2012;51(8):963‐974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Datta NR, Stutz E, Rogers S, et al. Clinical estimation of alpha/beta values for prostate cancer from isoeffective phase III randomized trials with moderately hypofractionated radiotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(7):883‐894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zaorsky NG, Yu JB, McBride SM, et al. Prostate cancer radiation therapy recommendations in response to COVID‐19. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020;5(4):659‐665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Widmark A, Gunnlaugsson A, Beckman L, et al. Ultra‐hypofractionated versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: 5‐year outcomes of the HYPO‐RT‐PC randomised, non‐inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10196):385‐395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Saito M, Suzuki T, Sugama Y, et al. Comparison of rectal dose reduction by a hydrogel spacer among 3D conformal radiotherapy, volumetric‐modulated arc therapy, helical tomotherapy, CyberKnife and proton therapy. J Radiat Res. 2020;61(3):487‐493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ogita M, Yamashita H, Nozawa Y, et al. Phase II study of stereotactic body radiotherapy with hydrogel spacer for prostate cancer: acute toxicity and propensity score‐matched comparison. Radiat Oncol. 2021;16(1):107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kundu P, Lin EY, Yoon SM, et al. Rectal radiation dose and clinical outcomes in prostate cancer patients treated with stereotactic body radiation therapy with and without hydrogel. Front Oncol. 2022;12:853246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fischer‐Valuck BW, Chundury A, Gay H, et al. Hydrogel spacer distribution within the perirectal space in patients undergoing radiotherapy for prostate cancer: impact of spacer symmetry on rectal dose reduction and the clinical consequences of hydrogel infiltration into the rectal wall. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2017;7(3):195‐202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hwang ME, Black PJ, Elliston CD, et al. A novel model to correlate hydrogel spacer placement, perirectal space creation, and rectum dosimetry in prostate stereotactic body radiotherapy. Radiat Oncol. 2018;13(1):192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu H, Borden L, Wiant D, et al. Proposed hydrogel‐implant quality score and a matched‐pair study for prostate radiation therapy. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2020;10(3):202‐208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang K, Mavroidis P, Royce TJ, et al. Prostate stereotactic body radiation therapy: an overview of toxicity and dose response. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;110(1):237‐248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fiorino C, Sanguineti G, Cozzarini C, et al. Rectal dose‐volume constraints in high‐dose radiotherapy of localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57(4):953‐962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang Y, Zolnay A, Incrocci L, et al. A quality control model that uses PTV‐rectal distances to predict the lowest achievable rectum dose, improves IMRT planning for patients with prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2013;107(3):352‐357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Paetkau O, Gagne IM, Alexander A. SpaceOAR(c) hydrogel rectal dose reduction prediction model: a decision support tool. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2020;21(6):15‐25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grossman CE, Folkert MR, Lobaugh S, et al. Quality metric to assess adequacy of hydrogel rectal spacer placement for prostate radiation therapy and association of metric score with rectal toxicity outcomes. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2023;8(4):101070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eckert F, Alloussi S, Paulsen F, et al. Prospective evaluation of a hydrogel spacer for rectal separation in dose‐escalated intensity‐modulated radiotherapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Whalley D, Hruby G, Alfieri F, et al. SpaceOAR hydrogel in dose‐escalated prostate cancer radiotherapy: rectal dosimetry and late toxicity. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2016;28(10):e148‐e154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fukumitsu N, Mima M, Demizu Y, et al. Separation effect and development of implantation technique of hydrogel spacer for prostate cancers. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2022;12(3):226‐235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Studenski MT, Delgadillo R, Xu Y, et al. Margin verification for hypofractionated prostate radiotherapy using a novel dose accumulation workflow and iterative CBCT. Phys Med. 2020;77:154‐159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Poon DMC, Yuan J, Yang B, et al. A prospective study of Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy (SBRT) with concomitant Whole‐Pelvic Radiotherapy (WPRT) for high‐risk localized prostate cancer patients using 1.5 Tesla magnetic resonance guidance: the preliminary clinical outcome. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(14):3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mariados NF, Orio PF, Schiffman Z, et al. Hyaluronic acid spacer for hypofractionated prostate radiation therapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncology. 2023;9(4):511‐518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kamran SC, McClatchy DM 3rd, Pursley J, et al. Characterization of an iodinated rectal spacer for prostate photon and proton radiation therapy. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2022;12(2):135‐144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]