Abstract

Objectives

Burnout is common among medical personnel in China and may be related to excessive and persistent work-related stressors by different specialties. The aims of this study were to assess the prevalence of burnout, work overload and work-life imbalance according to different specialties and to explore the effect of specialty, work overload and work-life imbalance on burnout among medical personnel.

Design

A cross-sectional study.

Setting

This study was conducted in 1 tertiary general public hospital, 2 secondary general hospitals and 10 community health service stations in Liaoning, China.

Participants

A total of 3299 medical personnel participated in the study.

Methods

We used the 15-item Chinese version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory General Survey (MBI-GS) to measure burnout. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to explore the association between medical specialty, work overload, work-life imbalance and burnout.

Results

3299 medical personnel were included in this study. The prevalence of burnout, severe burnout, work overload and work-life imbalance were 88.7%, 13.6%, 23.4% and 23.2%, respectively. Compared with medical personnel in internal medicine, working in obstetrics and gynaecology (OR=0.61, 95% CI 0.38, 0.99) and management (OR=0.45, 95% CI 0.28, 0.72) was significantly associated with burnout, and working in ICU (Intensive Care Unit)(OR=2.48, 95% CI 1.07, 5.73), surgery (OR=1.66, 95% CI 1.18, 2.35) and paediatrics (OR=0.24, 95% CI 0.07, 0.81) was significantly associated with severe burnout. Work overload and work-life imbalance were associated with higher ORs for burnout (OR=1.64, 95% CI 1.16, 2.32; OR=2.79, 95% CI 1.84, 4.24) and severe burnout (OR=4.33, 95% CI 3.43, 5.46; OR=3.35, 95% CI 2.64, 4.24).

Conclusions

Burnout, work overload and work-life imbalance were prevalent among Chinese medical personnel but varied considerably by clinical specialty. Burnout may be reduced by decreasing work overload and promoting work-life balance across different specialties.

Keywords: Burnout, Occupational Stress, PUBLIC HEALTH

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This study has a relatively large sample size and covers almost all specialties, including clinical departments and auxiliary departments.

This study uses the Chinese version of Maslach Burnout Inventory General Survey (MBI-GS) scale to measure burnout, which has been widely validated.

The present study provides direct evidence that burnout, work overload and work-life imbalance among medical personnel varied across specialties, and interventions to reduce burnout should be applied according to the particular situation of specialties.

All participants are from the same geographical area, which may limit generalisability.

Introduction

Burnout is a psychological syndrome associated with excessive and persistent work-related stressors and typically presents as emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and reduced personal accomplishment.1 Knowing the adverse effects of burnout is essential for physical and mental health of medical personnel and also to ensure medical safety and medical quality. Work-related consequences may include detrimental psychological outcomes of medical personnel,2 a higher possibility of medical errors, poor doctor-patient relationship,3 4 low-quality nursing for patients,5 impeded learning, high turnover intention and even tend to commit suicide.6

Medical personnel, a particular occupational population that deals with the cure of diseases and faces suffering and mortality directly, are confronted with more stress, work-load and are more vulnerable to mental disorders, such as burnout, than the general population.7–9 According to previous studies, the overall burnout prevalence ranged from 0% to 80.5% among physicians in the USA.10 Medical personnel are also recognised as high-risk population for burnout in China, as the burnout prevalence is up to 66.5–87.8%.11 It is noteworthy that the large population and limited medical source of China may continue to exacerbate the risk of burnout among medical personnel. Therefore, it is important to pay attention to burnout of Chinese medical personnel and to identify the factors associated with burnout that could potentially be addressed to lower the risks of burnout.

Studies have found substantial differences in the prevalence of burnout by specialty.12–15 In a study of US physicians, the burnout rate was highest in emergency medicine and lowest in preventive medicine/occupational medicine.12 A study among 3588 US resident physicians reported that urology has the highest rate of burnout, followed by neurology and ophthalmology.15 A study of Dutch resident physicians found that clinical setting and type of specialty appear to play a role in burnout.14 The study conducted by Grinberg et al showed that nursing staff in emergency medicine may develop a high degree of burnout compared with nursing staff in inpatient departments.16 Further evidence from China is needed to confirm that burnout varied by specialty among medical personnel. Moreover, those studies that focused on specialty differences in burnout among medical personnel did not include ICU (Intensive Care Unit)physicians, who are considered to have high rate of burnout.

It has been recognised that burnout is the result of continued exposure to work-related stressful events.17 Previous study showed that more work-load and work-life imbalance may compound work-related stress, which exacerbates the burnout of medical personnel.18–21 The purposes of this study were to assess the prevalence of burnout, work overload and work-life imbalance according to different specialties and to explore the effect of specialty, work overload and work-life imbalance on burnout among medical personnel in Liaoning, China. The present study therefore evaluates the hypothesis that (1) burnout, work overload and work-life imbalance among medical personnel varies in different specialties; and (2) specialty, work overload and work-life imbalance are all related to burnout.

Methods

Study population

We conducted a cross-sectional survey from January 2012 to December 2013 in Liaoning Province. According to the economic level (high, median, low) of Liaoning, three cities (Shenyang, Anshan and Panjin) and three countries (Dagui, Qingyuan, Xifeng) were selected. In each city, 1 tertiary general public hospital, 2 secondary general hospitals and 10 community health service stations were sampled randomly. In each country, 1 country hospital, 1 country hospital of traditional Chinese medical and 10 township health clinics were sampled randomly. Questionnaires were directly distributed to medical personnel, including physicians and nurses after obtaining written informed consent. The questionnaire in which missing values exceeded 20% was regarded as invalid. We received an effective response from 3299 medical personnel, with an effective response rate of 91.46%.

Assessment of work overload

Workload was determined with the question, ‘How about your current work-load?’ Answers were given on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 4 (response options: 1=over load; 2=full load; 3=about half; 4=little load). Those who answered 1 was defined as work overload.

Assessment of work-life imbalance

Work-life imbalance in the present study was assessed by the item, ‘Are you experiencing difficulty with your work-life balance?’ Answers were given on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (response options: 1=almost no; 2=small; 3=general; 4=big; 5=very big). Individuals who answered 1–3 were considered to experience work-life balance, while those who answered 4–5 were considered to experience work-life imbalance.

Assessment of burnout

Burnout in the present study was assessed using the Chinese version of Maslach Burnout Inventory General Survey (MBI-GS) with a total of 15 items. Based on the frequency of occurrence of the specific work feelings, each item has seven possible responses, ‘never’, ‘seldom’, ‘sometimes’, ‘often’, ‘frequent’, ‘very frequent’ and ‘daily,’ and the response was scored from 0 for ‘never’ to 6 for ‘daily.’ The MBI-GS includes three dimensions: emotional exhaustion (five items), depersonalisation (four items) and reduced personal accomplishment (six items). According to the previous studies,22–24 the following equation was used to calculate the weighted sum score of burnout:

On the basis of their scores of burnout (range 0–6), participants were divided into three groups, including no burnout (range 0–1.49), moderate burnout (range 1.50–3.49) and severe burnout (range 3.50–6.0). The burnout case is someone who has experienced moderate to severe burnout.24 In this study, the Cronbach’s α for the MBI-GS was 0.868. The internal consistency coefficients were 0.949, 0.932 and 0.913 for emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and reduced personal accomplishment, respectively.

Measurements of sociodemographic characteristics

Sociodemographic factors included gender, age, marital status, self-reported income level, professional title, years of work, night shift and chronic disease. Age was divided into four group: <30, 30–39, 40–49 and ≥50 years. We categorised marital status as married and others. Years of work was marked as <10, 10–19, 20–29 and 30 years or more. Professional title was categorised as junior, intermediate or above. Self-reported income level was defined as low, middle or above. Night shift was determined by the following question: ‘Do you work night shift (yes/no)’? Chronic disease was assessed by the self-reported question, ‘Do you have any chronic disease (yes/no)?’

Statistical analysis

Categorical and continuous variables were described as percentages or mean±SD, and for the categorical variables, groups for which the response rate <5% were merged. Categorical variables were examined by χ2 test. We used multivariable logistic regression models to explore the association of specialty with burnout, work overload and work-life imbalance. For each analysis, specialty, age, gender, marital status, chronic disease, professional title, self-reported income level, years of work and night shift were adjusted. Work overload and work-life imbalance were adjusted separately to the models for work-life imbalance and work overload. Data were analysed using the R software (V.3.5.2).

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of our research.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants

A total of 3299 medical personnel in Liaoning responded to this survey, including 909 males (27.6%) and 2390 females (72.4%). Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. Among the participants, the highest number belonged in the 30–39 year group (32.7% vs 21.0% vs 31.1% vs 15.2%), with the mean age of 39.1±10.0 (range 19–77 years) and more likely to be married (80.8% vs 19.2%), junior title (53.1% vs 46.9%) and reported to had a lower income (65.5% vs 34.5%) and had no chronic disease (84.2% vs 15.8%).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

| n (%) | |

| Specialty | |

| Internal medicine | 669 (20.3) |

| ICU | 31 (0.9) |

| Emergency medicine | 148 (4.5) |

| Surgery | 558 (16.9) |

| Oncology | 55 (1.7) |

| Ophthalmology | 85 (2.6) |

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | 252 (7.6) |

| Medical detection | 358 (10.9) |

| Operation room | 100 (3.0) |

| Family medicine | 321 (9.7) |

| Management | 175 (5.3) |

| Pharmacy | 85 (2.6) |

| Paediatrics | 81 (2.5) |

| Other | 381 (8.5) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 909 (27.6) |

| Female | 2390 (72.4) |

| Age group (years) | |

| <30 | 694 (21.0) |

| 30–39 | 1076 (32.7) |

| 40–49 | 1027 (31.1) |

| ≥50 | 502 (15.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Other | 632 (19.2) |

| Married | 2661 (80.8) |

| Self-reported income level | |

| Low | 2150 (65.5) |

| Meddle and above | 1130 (34.5) |

| Professional title | |

| Junior | 1745 (53.1) |

| Intermediate and above | 1539 (46.9) |

| Years of work | |

| <10 | 904 (27.7) |

| 10–19 | 753 (23.1) |

| 20–29 | 859 (26.3) |

| ≥30 | 750 (23.0) |

| Night shift | |

| No | 1651 (50.0) |

| Yes | 1648 (50.0) |

| Chronic disease | |

| No | 2769 (84.2) |

| Yes | 519 (15.8) |

*p<0.05. Other specialties include psychiatry, stomatology, infectious disease and orthopaedics.

ICU, Intensive Care Unit.

Prevalence of burnout, work overload and work-life imbalance by specialty

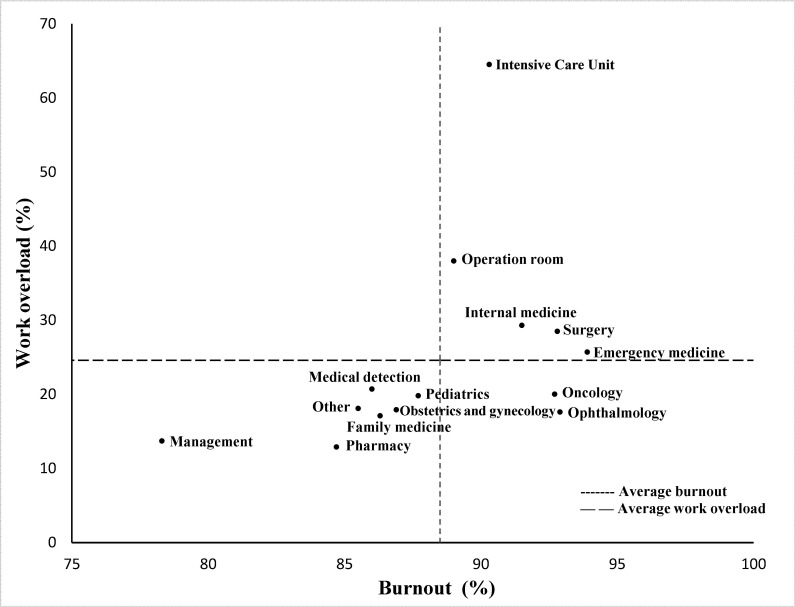

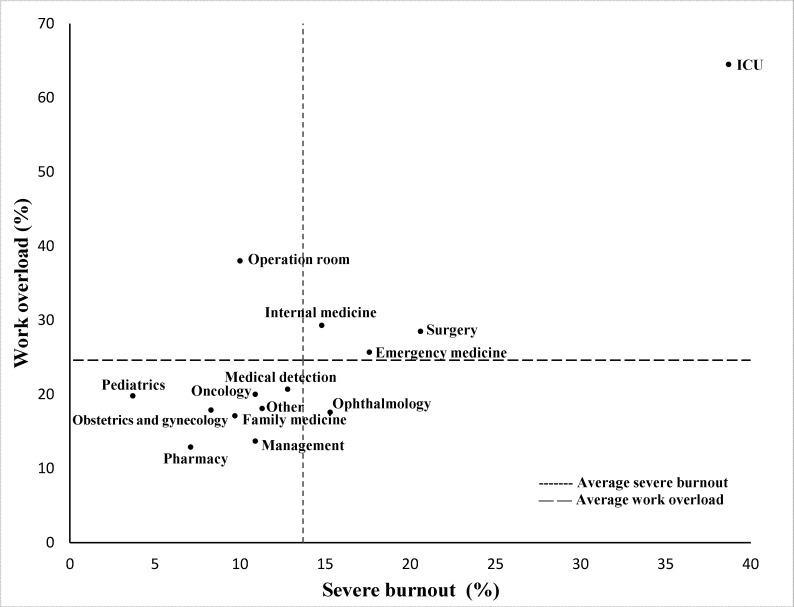

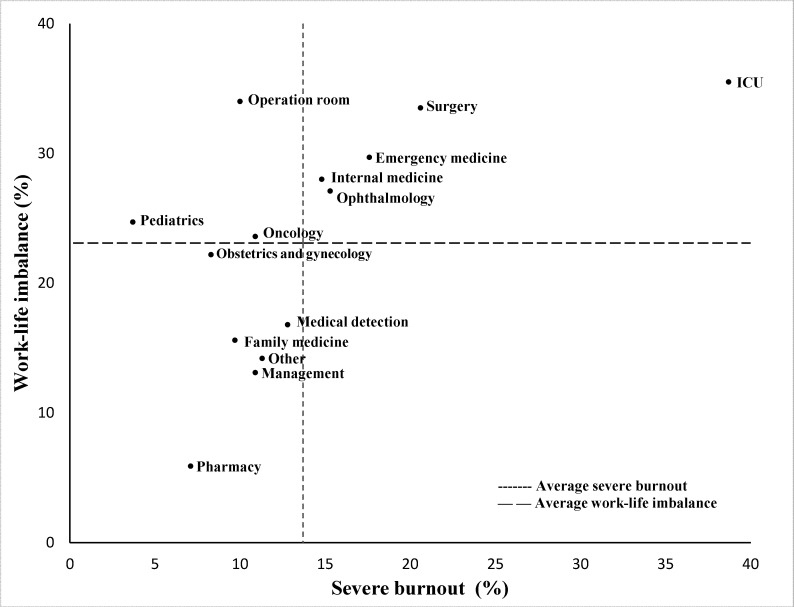

Overall, the prevalence of burnout, severe burnout, work overload and work-life imbalance were 88.7%, 13.6%, 23.4% and 23.2%, respectively. The prevalence of burnout, work overload and work-life imbalance by specialty is shown in table 2. In terms of burnout, the highest prevalence was presented in emergency medicine (93.9%), followed by ophthalmology (92.9%) and surgery (92.8%); the lowest prevalence was presented in management (78.3%) (p<0.05). In terms of severe burnout, the highest prevalence was presented in the ICU (38.7%), followed by surgery (20.6%) and emergency medicine (17.6%); the lowest prevalence was presented in paediatrics (3.7%), pharmacy (7.1%), and obstetrics and gynaecology (8.3%) (p<0.05). ICU (64.5%) has the highest prevalence in work overload; the following three are operating room (38.0%), surgery (28.5%) and internal medicine (29.3%), while pharmacy (12.9%) has the lowest work overload rate. For work-life imbalance, ICU (35.5%), operating room (34.0%) and surgery (33.5%) are the top three specialties that cannot deal with work-life balance, while pharmacy (5.9%) can balance work and life well.

Table 2.

Prevalence of burnout, work overload and work-life imbalance by specialty

| Total n (%) |

Burnout score Mean±SD |

Burnout n (%) |

Severe burnout n (%) |

Work overload n (%) |

Work-life imbalance n (%) |

|

| Total | 3299 | 2.5±1.0 | 2927 (88.7) | 450 (13.6) | 771 (23.4) | 767 (23.2) |

| Specialty | ||||||

| Internal medicine | 669 (20.3) | 2.6±1.0* | 612 (91.5)* | 99 (14.8)* | 196 (29.3)* | 187 (28.0)* |

| ICU | 31 (0.9) | 3.2±1.2 | 28 (90.3) | 12 (38.7) | 20 (64.5) | 11 (35.5) |

| Emergency medicine | 148 (4.5) | 2.6±1.0 | 139 (93.9) | 26 (17.6) | 38 (25.7) | 44 (29.7) |

| Surgery | 558 (16.9) | 2.7±1.1 | 518 (92.8) | 115 (20.6) | 159 (28.5) | 187 (33.5) |

| Oncology | 55 (1.7) | 2.7±0.8 | 51 (92.7) | 6 (10.9) | 11 (20.0) | 13 (23.6) |

| Ophthalmology | 85 (2.6) | 2.6±1.0 | 79 (92.9) | 13 (15.3) | 15 (17.6) | 23 (27.1) |

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | 252 (7.6) | 2.3±0.9 | 219 (86.9) | 21 (8.3) | 45 (17.9) | 56 (22.2) |

| Medical detection | 358 (10.9) | 2.4±1.1 | 308 (86.0) | 46 (12.8) | 74 (20.7) | 60 (16.8) |

| Operation room | 100 (3.0) | 2.4±0.8 | 89 (89.0) | 10 (10.0) | 38 (38.0) | 34 (34.0) |

| Family medicine | 321 (9.7) | 2.3±0.9 | 277 (86.3) | 31 (9.7) | 55 (17.1) | 50 (15.6) |

| Management | 175 (5.3) | 2.2±1.0 | 137 (78.3) | 19 (10.9) | 24 (13.7) | 23 (13.1) |

| Pharmacy | 85 (2.6) | 2.2±0.9 | 72 (84.7) | 6 (7.1) | 11 (12.9) | 5 (5.9) |

| Paediatrics | 81 (2.5) | 2.2±0.7 | 71 (87.7) | 3 (3.7) | 16 (19.8) | 20 (24.7) |

| Other | 381 (8.5) | 2.4±1.0 | 327 (85.5) | 43 (11.3) | 69 (18.1) | 54 (14.2) |

*p<0.05. Other specialties include psychiatry, stomatology, infectious disease and orthopaedics.

ICU, Intensive Care Unit.

Figures 1–4 show the categorisation of the 14 specialties based on the prevalence of burnout, severe burnout, work overload and work-life imbalance in their specialty. ICU, operation room, emergency medicine, surgery and internal medicine have higher burnout rate, higher work overload rate and higher work-life imbalance rate. Differed from all other specialties, ICU was particularly high for the prevalence of severe burnout, work overload and work-life imbalance.

Figure 1.

Burnout and work overload by specialty.

Figure 2.

Burnout and work-life imbalance by specialty.

Figure 3.

Severe burnout and work overload by specialty.

Figure 4.

Severe burnout and work-life imbalance by specialty.

Association of medical specialty with burnout and severe burnout

Regression analysis was used to explore the relationship of medical specialty with burnout and severe burnout (table 3). We controlled for age, gender, marital status, chronic disease, professional title, self-reported income level, years of work, night shift, work overload and work-life imbalance. Compared with medical personnel in internal medicine, working in obstetrics and gynaecology (OR=0.61, 95% CI 0.38,0.99) and management (OR=0.45, 95% CI 0.28, 0.72) was significantly associated with burnout, and working in ICU (OR=2.48, 95% CI 1.07, 5.73), surgery (OR=1.66, 95% CI 1.18, 2.35) and paediatrics (OR=0.24, 95% CI 0.07, 0.81) was significantly associated with severe burnout.

Table 3.

Association of medical specialty, work overload and work-life imbalance with burnout

| Burnout OR (95% CI) |

Severe burnout OR (95% CI) |

|

| Specialty | ||

| Internal medicine | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| ICU | 0.54 (0.15, 1.89) | 2.48 (1.07, 5.73) |

| Emergency medicine | 1.59 (0.70, 3.62) | 1.48 (0.87, 2.51) |

| Surgery | 1.16 (0.74, 1.81) | 1.66 (1.18, 2.35) |

| Oncology | 1.15 (0.39, 3.34) | 0.88 (0.34, 2.24) |

| Ophthalmology | 1.24 (0.51, 3.02) | 1.37 (0.68, 2.76) |

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | 0.61 (0.38, 0.99) | 0.65 (0.38, 1.13) |

| Medical detection | 0.71 (0.46, 1.08) | 1.25 (0.81, 1.91) |

| Operation room | 0.68 (0.33, 1.40) | 0.58 (0.28, 1.19) |

| Family medicine | 0.77 (0.50, 1.20) | 0.95 (0.59, 1.54) |

| Management | 0.45 (0.28, 0.72) | 1.19 (0.66, 2.15) |

| Pharmacy | 0.80 (0.41, 1.58) | 0.94 (0.37, 2.36) |

| Paediatrics | 0.67 (0.32, 1.39) | 0.24 (0.07, 0.81) |

| Other | 0.70 (0.46, 1.06) | 1.12 (0.73, 1.73) |

| Work overload | ||

| No | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Yes | 1.64 (1.16, 2.32) | 4.33 (3.43, 5.46) |

| Work-life imbalance | ||

| No | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Yes | 2.79 (1.84, 4.24) | 3.35 (2.64, 4.24) |

Regression analysis controlled for age, gender, marital status, chronic disease, professional title, self-reported income level, years of work and night shift.

ICU, Intensive Care Unit.

Association of work overload and work-life imbalance with burnout and severe burnout

Work overload and work-life imbalance were associated with higher ORs for burnout (OR=1.64, 95% CI 1.16, 2.32; OR=2.79, 95% CI 1.84, 4.24) and severe burnout (OR=4.33, 95% CI 3.43, 5.46; OR=3.35, 95% CI 2.64, 4.24) after controlling for specialty, age, gender, marital status, chronic disease, professional title, self-reported income level, years of work and night shift (table 3). Meanwhile, work overload and work-life imbalance were risk factors for each other.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we found that burnout was prevalent among Chinese medical personnel. About 88.7% of medical personnel in China experienced burnout, with 13.6% experiencing severe burnout. The prevalence of burnout, work overload and work-life imbalance varies across specialties. Working in ICU and surgery was related to higher odds of severe burnout, and working in obstetrics and gynaecology, paediatrics and management was related to lower odds of burnout. Simultaneously, work overload and work-life imbalance are all related to burnout and severe burnout.

Our findings suggest that medical personnel have a high prevalence of burnout in China but differed based on specialty. The results were consistent with a few other studies12 14 15 25 26 that showed that burnout rates varied significantly by specialty, with medical personnel working in emergency medicine and surgery reporting higher rates and working in obstetrics and gynaecology, family medicine and paediatrics reporting lower rates. Our analyses also included severe burnout rates of these specialties, further confirming that variability is large between specialties. This may be in line with the traditional perception of medical personnel and medical specialty. Dyrbye et al suggested that the reason for the differences in burnout rates by specialty among physicians is the unique characteristics of the work intrinsic to these specialties.15 Medical personnel faced greater work pressure, work intensity and medical responsibilities. Nevertheless, different specialties correspond to different job contents; working in obstetrics and gynaecology may involve the development and birth of a new life and working in emergency medicine needs to provide emergent medical assistance at all times. It is the unique characteristics of this inherent medical work that determine the differences in burnout rates among medical personnel across specialties.

In this study, we show that the prevalence of burnout for ICU in China is not the highest among all specialties; however, the prevalence of severe burnout for ICU was significantly higher than other specialties, which was at least 18% higher, up to 38.7%. In analogy to our findings, a study conducted in China reported that burnout rates among ICU physicians exceeded 80% and severe burnout exceeding 40% in this population.27 Thus, contrasted with other specialties, the severe burnout of ICU physicians should be given sufficient attention. In addition, the prevalence of workload and work-life imbalance for ICU was the highest among all specialties, especially workload, which was at least 26% higher, up to 64.5%. Excessive workload and work-life imbalance have accounted for some degrees of the risk of severe burnout increasing for ICU. According to our study, workload and work-life imbalance were important severe burnout-related factors and this may result in higher rates of severe burnout among ICU physicians than in other specialties.

The results of the present study revealed that the rates of work overload and work-life imbalance among medical personnel vary by specialty, and workload and work-life imbalance were strongly associated with burnout. Similar to burnout, the differences between specialty for workload and work-life imbalance may also arise from the unique characteristics of the inherent medical specialty. ICU, surgery and operation room are aptly ready to handle critical medical situation; therefore, these specialties may have unpredictable and longer working hours as well as work overload and work-life imbalance. Pharmacy, management and family medicine rarely experience medical emergencies and rotating night shift work; therefore, these specialties may have relatively fixed working hours and balance work and life well. The association of workload and work-life imbalance with burnout from our study is concordant with prior findings.6 17 21 25 28 29 Indeed, work overload is recognised as the source of burnout as early as 1997.28 In recent years, the hazardous effect of work-life imbalance on burnout has become appreciated.20 30 Our results provide evidence, in addition to that in the existing literature, with respect to the association of work overload and work-life imbalance with severe burnout. Furthermore, this relationship may be widespread within all medical specialties. Remarkably, work overload and work-life imbalance were also risk factors for each other.

This study has several limitations. First of all, while most of the specialties are involved in our study, several specialties are included relatively fewer participants, thus some specialties are under-represented. Second, all participants are from Liaoning, China, which may limit generalisability. Third, the results of this cross-sectional design study cannot provide any causal inference. Fourth, the definition of burnout is not standardised and this study used the MBI-GS to assess burnout. Despite that different instruments to measure burnout are all well validated, with high correlation and non-differential,18 caution is warranted when comparing the results from various studies. Finally, work overload and work-life imbalance are based on subjective feelings and may have bias in self-reporting.

Conclusion

Burnout, work overload and work-life imbalance were prevalent among Chinese medical personnel but varied considerably by clinical specialty. Burnout may be reduced by decreasing work overload and promoting work-life balance across different specialties.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the support from the Liaoning Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention for their technological guidance.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the study design and development of survey questions. HM, YL, QX, JN and GP performed this survey in Liaoning. HM, YL, QX, JN, CM conducted the analysis. HM, YD, YG, WS, LY and GP drafted the manuscript, with final review and contributions from HM and GP. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Science and Technology Innovation Team of China Medical University (grant number: CXTD2022006).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

All experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of China Medical University. All methods were carried out in accordance with the Ethics Committee of China Medical University. Informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from all participants. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter M. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. 3rd edn. Palo Alot, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. Burnout and suicidal Ideation among U.S. medical students. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:334–41. 10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pham JC, Aswani MS, Rosen M, et al. Reducing medical errors and adverse events. Annu Rev Med 2012;63:447–63. 10.1146/annurev-med-061410-121352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kalmbach DA, Arnedt JT, Song PX, et al. Sleep disturbance and short sleep as risk factors for depression and perceived medical errors in first-year residents. Sleep 2017;40:zsw073. 10.1093/sleep/zsw073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American Surgeons. Ann Surg 2010;251:995–1000. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rothenberger DA. Physician burnout and well-being: a systematic review and framework for action. Dis Colon Rectum 2017;60:567–76. 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Issa BA, Yussuf AD, Olanrewaju GT, et al. Mental health of doctors in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J 2014;19:178. 10.11604/pamj.2014.19.178.3642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Győrffy Z, Dweik D, Girasek E. Workload, mental health and burnout indicators among female physicians. Hum Resour Health 2016;14:12. 10.1186/s12960-016-0108-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meerten M, Rost F, Bland J, et al. Self-referrals to a doctors’ mental health service over 10 years. Occup Med (Lond) 2014;64:172–6. 10.1093/occmed/kqt177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians. JAMA 2018;320:1131. 10.1001/jama.2018.12777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lo D, Wu F, Chan M, et al. A systematic review of burnout among doctors in China: a cultural perspective. Asia Pac Fam Med 2018;17:3. 10.1186/s12930-018-0040-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90:1600–13. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among American Surgeons. Ann Surg 2009;250:463–71. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ac4dfd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Prins JT, Hoekstra-Weebers JEHM, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, et al. Burnout and engagement among resident doctors in the Netherlands: a national study. Med Educ 2010;44:236–47. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03590.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. Association of clinical specialty with symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among US resident physicians. JAMA 2018;320:1114–30. 10.1001/jama.2018.12615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Grinberg K, Revach C, Lipsman G. Violence in hospitals and burnout among nursing staff. Int Emerg Nurs 2022;65:101230. 10.1016/j.ienj.2022.101230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Debets M, Scheepers R, Silkens M, et al. Structural equation Modelling analysis on relationships of job demands and resources with work engagement, burnout and work ability: an observational study among physicians in Dutch hospitals. BMJ Open 2022;12:e062603. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-062603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hämmig O. Explaining burnout and the intention to leave the profession among health professionals – a cross-sectional study in a hospital setting in Switzerland. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:785. 10.1186/s12913-018-3556-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gregory ME, Russo E, Singh H. Electronic health record alert-related workload as a predictor of burnout in primary care providers. Appl Clin Inform 2017;8:686–97. 10.4338/ACI-2017-01-RA-0003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guille C, Frank E, Zhao Z, et al. Work-family conflict and the sex difference in depression among training physicians. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:1766–72. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, et al. Relationship between work-home conflicts and burnout among American Surgeons: a comparison by sex. Arch Surg 2011;146:211–7. 10.1001/archsurg.2010.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xu W, Pan Z, Li Z, et al. Job burnout among primary healthcare workers in rural China: a multilevel analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:727. 10.3390/ijerph17030727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu Y, Zou L, Yan S, et al. Burnout and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among medical staff two years after the COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan, China: social support and resilience as mediators. J Affect Disord 2023;321:126–33. 10.1016/j.jad.2022.10.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wen J, Cheng Y, Hu X, et al. Workload, burnout, and medical mistakes among physicians in China: a cross-sectional study. Biosci Trends 2016;10:27–33. 10.5582/bst.2015.01175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1377–85. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xiao Y, Dong D, Zhang H, et al. Burnout and well-being among medical professionals in China: a national cross-sectional study. Front Public Health 2021;9:761706. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.761706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang J, Hu B, Peng Z, et al. Prevalence of burnout among intensivists in Mainland China: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. Crit Care 2021;25:8. 10.1186/s13054-020-03439-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maslach C, Leiter M. The Truth About Burnout: How Organizations Cause Personal Stress and What To Do About It. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc 2017;92:129–46. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ariely D, Lanier WL. Disturbing trends in physician burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance: dealing with malady among the nation’s Healers. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90:1593–6. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.