Imagine this. You are a doctor in Tanzania. Annual health expenditure is $4 (£2.50) per head; malaria, tuberculosis, and maternal death are pressing problems; 150 000 people died from AIDS last year; and 9% of adults are infected with HIV.1 Life expectancy is 53 years. As an oncologist in the country’s only cancer centre, you saw 1650 new cases last year. This probably represents about 10% of the total—your centre is inaccessible to the rest of the population. Around 90% of patients present with late stage, incurable disease. How do you begin to tackle cancer in such a context? This was the stark challenge posed by Twalib Ngoma of the Tanzania Cancer Center to a conference on “Cancer Strategies for the New Millennium.”2 This report synthesises selected themes from the discussion on how best to combat cancer in the developing world.

Summary points

By 2020, cancer incidence and mortality are set to double, and more than 70% of new cancers will arise in people in the developing world

The public health potential of curative treatment seems limited as the cancers that will predominate—stomach, liver, and lung—are relatively unresponsive to current treatments

Rational approaches identify cancer prevention as a top priority

Tobacco control and hepatitis B vaccination are cost effective prevention strategies, with health benefits that reach beyond cancer

Development of cancer vaccines and low technology approaches to early detection and treatment offer an alternative to transferring the resource intensive procedures used in richer countries

The global picture

By 2020, new cancer cases will double to 20 million a year. Already, over half of new cancers arise in people in the developing world; by 2020 the proportion will reach 70%. Cancer deaths are also set to increase, from 6 million to 12 million annually.3

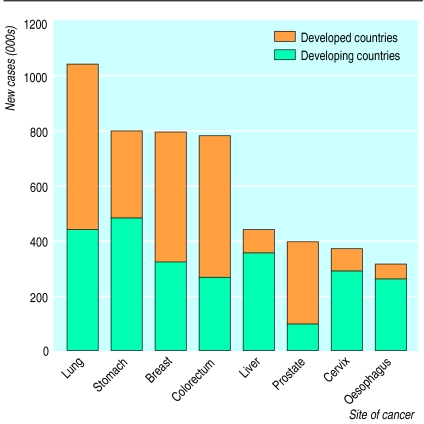

The causes of cancer vary world wide. In developed countries, tobacco is a major culprit, causing 1 in 3 cancer deaths. In the developing world, infection plays the largest part; it is responsible for almost 1 in 4 cancer deaths. One reason for these differences is the deadly impact of decades of widespread tobacco use in richer countries—an epidemic now being propagated globally. Another is the high prevalence of chronic infection in the developing world—in particular, with human papillomavirus, which causes cervical cancer; Helicobacter pylori, implicated in stomach cancer; and hepatitis B and C viruses, major causes of liver cancer. Together, these agents account for over 90% of cancers related to infection.4 Variations in cause are reflected in differences in the cancers that predominate in different parts of the world (fig 1).5 While the top five cancers in developed countries are (in descending order) lung, colorectum, breast, stomach, and prostate cancer, in developing countries the most common cancers are those of the stomach, lung, liver, breast, and cervix.

Figure 1.

The eight most frequent cancers in 1990, ranked by overall incidence world wide

Focusing efforts

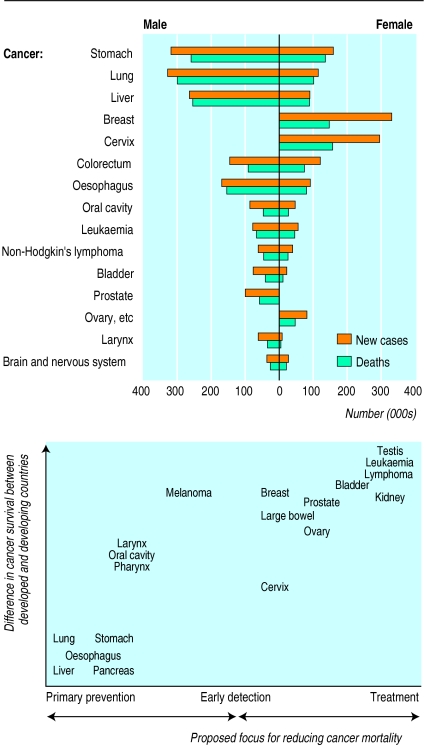

What should be the relation between prevention, detection, and management? Comparison of cancer survival between rich and poor countries can inform priorities (see fig 2).6 For some cancers the difference between rich and poor countries is relatively small, reflecting the modest effects of even optimal existing treatments. These cancers include lung, stomach, and liver cancers, projected to be among the 15 leading causes of death world wide in 2020.7 For others, such as leukaemia and lymphoma, survival is much better in developed countries. For cancers falling between the extremes—including cancer of the cervix and breast—early detection greatly improves the potential for effective treatment (fig 2).

Figure 2.

Incidence of and mortality from the 15 most common cancers in developing countries, 1990, and suggested focus for reducing mortality from specific cancers in developing countries

Rational assessments of the potential public health impact of prevention, early detection, and treatment identify prevention as the top priority. For detection and treatment, priorities are influenced by the interplay between basic research and technological development, and between the available technology and its implementation. Many screening and treatment protocols used in richer countries do not transfer readily to countries where resources—human, technical, and financial—are in short supply. Implementation of affordable protocols, coupled with research and development of new technologies more suited to environments with fewer resources, might prove more fruitful.

Low technology approaches

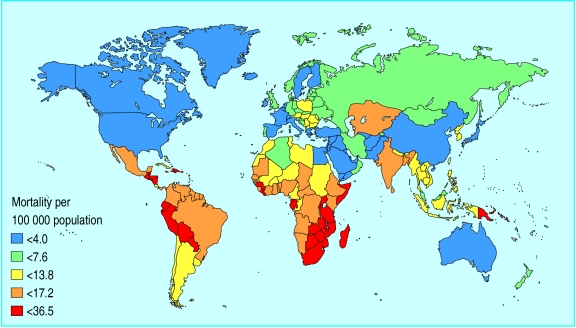

Take, for example, cervical cancer, which has a known cause, an accurate detection test, and can be treated effectively. Although cervical cancer has declined in many industrialised countries, it remains the most deadly cancer among women in the developing world, where the increased risk of infection with papillomavirus is compounded by the limited capacity for screening and treatment. Each year over half a million new cases occur—almost 80% in developing countries—and some 250 000 women die from the disease (fig 3). Over 99% of cervical cancers are associated with human papillomavirus.8 Barrier contraceptives could protect against infection, but even when these are available, women cannot always insist on their use. Research on contraceptives containing microbicide may ultimately yield benefits. However, infection and transmission of papillomavirus might be most effectively controlled if a vaccine were available.

Figure 3.

Mortality from cervical cancer in 1990 (per 100 000 age standardised world population)

Two prophylactic papillomavirus vaccines are being tested in clinical trials, as is a therapeutic vaccine that stimulates cell immunity against the oncogenic viral proteins E6 and E7. These vaccines could hold special promise for women in the developing world.

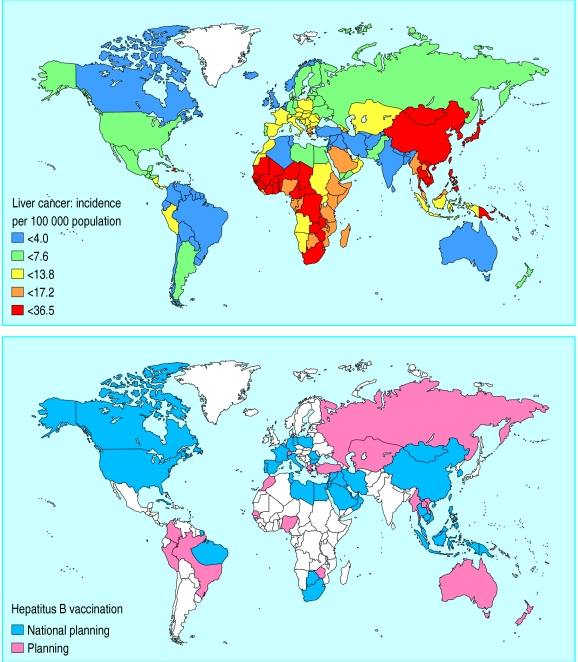

How can the promise become a reality? The meeting was told that in addition to being safe and effective, vaccines must be cheap and readily administered through existing health programmes. Much can be learnt from the experience with hepatitis B vaccination, which highlights the gap between technological advances and their application. Though an effective hepatitis B vaccine has been available since 1982, and WHO has promoted global vaccination since 1991, coverage remains poor. Two thirds of infants at risk in developing countries are unvaccinated (fig 4). Less than $2 (£1.25) will protect a child against hepatitis B,9 yet this is double the price of all six vaccines in WHO’s expanded programme of immunisation, and cost remains the major constraint. Finally, even if papillomavirus vaccines were to become available, many people are already infected. Early detection coupled with effective treatment must therefore play a crucial role for years to come.

Figure 4.

Although the incidence of liver cancer remains high in developing countries, two thirds of infants at risk of hepatitis B are unvaccinated. Above: liver cancer in males, 1990 (incidence per 100 000 age standardised world population); below: status of national, routine childhood immunisation programmes against hepatitis B in 1998

In industrialised countries, detection of cervical cancer relies on smear testing. Although cytological testing is feasible in some developing countries, systematic coverage and follow up are beyond the reach of many more. Research is under way into alternative detection methods that can be integrated into ongoing health programmes in resource-poor countries. One approach, known as VIA, involves visual inspection of the cervix after the application of acetic acid and can be performed by trained health workers. A study in India has shown that the specificity and the sensitivity of VIA in detecting early disease related changes are similar to those of cytology. Further research will assess whether VIA reduces mortality from cervical cancer and will evaluate its potential in case finding and screening.

Early detection is useful only where effective treatment is feasible. Traditionally, high grade precursor lesions of cervical cancer are treated with surgical conisation, which requires admission to hospital. One alternative is a “see and treat” approach. Suspect lesions identified by VIA are confirmed by colposcopy, and treated immediately using loop electrosurgical excision procedure or cryotherapy. This approach means that women diagnosed with a lesion are not lost to follow up. Loop excision has particular advantages in resource-poor environments—the equipment is relatively cheap and easy to operate, specialist surgical skills are not required, and complications are rare. Low technology strategies could also prove valuable in early detection of breast cancer. Breast examination by health workers can detect a substantial proportion of early breast cancers. Overall, the evidence suggests that it should be carried out routinely whenever women interact with health services.

Relieving suffering

Curative treatment is crucial. However, in the developing world, around 80% of cancer patients have late stage incurable disease when they are diagnosed. Clearly, health professionals have an ethical duty to prevent avoidable suffering. Effective pain relief should be an integral part of management, but unfortunately, access to palliative care is limited. Community based interventions can improve access, deliver effective pain relief and enhance social integration and quality of life, but they also raise equity issues. In many societies, the burden falls mainly on women, who may also be less likely to receive care should they themselves fall ill.

Local action, global action

Controlling cancer in different environments requires tailored strategies. What, then, can an international perspective add? One answer lies in recognising the potential for synergies with other health programmes and the need for concerted action at different levels—local, national, regional, and global.

Global priorities in cancer prevention (see fig 2) must balance the need for research, development, and implementation. For cancers with a high disease burden but low preventability—such as breast and prostate cancer—research into causes has high priority. Other cancers have a known cause, and for these, development of effective preventive strategies is a priority: for example, cervical cancer and papillomavirus vaccines. Finally, for cancers that can be prevented through established interventions, implementation has top priority. Hepatitis B vaccination in developing countries and mass media antitobacco campaigns are cost effective interventions with benefits that reach beyond cancer.

Rallying support for health promotion and disease prevention can prove tricky. Yet where community support can be mobilised, these programmes can yield results, even in resource-poor settings. In Kerala, India, for example, encouraging results are emerging from a community based programme to control cancers of the oral cavity, breast, and cervix. A cancer awareness programme was coupled with education of health professionals and the establishment of early detection centres. Almost 130 000 volunteers were mobilised, and education and advocacy carried out through schools and the media. Programmes at village level gave advice on prevention, encouraged people with early symptoms to seek assistance, and provided support during treatment and terminal illness. Success will be measured by changes in the cancer incidence, mortality, and survival; the stage of presentation; and the prevalence of tobacco use. Already, preliminary data show a decrease in the number of people presenting with late stage cancers.

Tobacco control is a high priority in health and a truly international concern. At present, throughout the world, someone dies from a tobacco related illness every 9 seconds. In 20 years, the toll will reach one death every 3 seconds, and 70% of these deaths will occur in the developing world. Behind the statistics lie forces that cannot readily be addressed locally, involving international trade, debt repayment, development policy, and communications. The WHO’s tobacco-free initiative takes an interdisciplinary approach to stemming the epidemic, building links with other international organisations, non-governmental organisations, the private sector, and the research community.

Communicating reality and vision

Much remains to be done to raise awareness and concern about cancer in the developing world. The yawning gap between poor and rich countries persists, and cheap effective technologies such as hepatitis B vaccine are not applied. There is a pressing need to deal pragmatically with today’s problems by setting realistic priorities. Yet health professionals also have a responsibility to expand what is feasible. As Article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states, “Everyone has the right ... to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.” This vision can be communicated through persuasive and practical arguments for placing cancer in developing countries squarely in context—and firmly on the agenda.

Acknowledgments

I thank N Muñoz and R Sankaranarayan for discussions and advice, and P Kleihues, DM Parkin, K Sikora, A Narinesingh, E LeGresley, and Y Daikh for their comments. Special thanks go to KJ Hughes.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.UNAIDS/WHO. Epidemiological fact sheet on HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted diseases. Geneva: UNAIDS/WHO; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organisation Programme on Cancer Control. Cancer strategies for the new millennium. Proceedings of a conference held at the Royal College of Physicians, London. 1998. www.who-pcc.iarc.fr/Publications/Publications.html ( www.who-pcc.iarc.fr/Publications/Publications.html; accessed2 March 1999.) ; accessed2 March 1999.) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJL, Lopez AD, editors. The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pisani P, Parkin DM, Muñoz N, Ferlay J. Cancer and infection: estimates of the attributable fraction in 1995. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:387–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parkin DM, Pisani P, Ferlay J. Estimates of the worldwide incidence of 25 major cancers in 1990. Int J Cancer. 1999;80:827–841. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990315)80:6<827::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pisani P, Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J. Estimates of the worldwide mortality from 25 major cancers in 1990. Int J Cancer 1999 (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Sankaranarayanan R, Black RJ, Parkin MD, editors. Cancer survival in developing countries. Lyons: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walboomers JMM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide J Pathol 1999 (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.WHO Expanded Programme on Immunisation. Hepatitis B vaccine—making global progress. Geneva: WHO; 1997. [Google Scholar]