Abstract

Historically, feline mediastinal lymphoma has been associated with young age, positive feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) status, Siamese breed and short survival times. Recent studies following widespread FeLV vaccination in the UK are lacking. The aim of this retrospective multi-institutional study was to re-evaluate the signalment, retroviral status, response to chemotherapy, survival and prognostic indicators in feline mediastinal lymphoma cases in the post-vaccination era. Records of cats with clinical signs associated with a mediastinal mass and cytologically/histologically confirmed lymphoma were reviewed from five UK referral centres (1998–2010). Treatment response, survival and prognostic indicators were assessed in treated cats with follow-up data. Fifty-five cases were reviewed. The median age was 3 years (range, 0.5–12 years); 12 cats (21.8%) were Siamese; and the male to female ratio was 3.2:1.0. Five cats were FeLV-positive and two were feline immunodeficiency-positive. Chemotherapy response and survival was evaluated in 38 cats. Overall response was 94.7%; complete (CR) and partial response (PR) rates did not differ significantly between protocols: COP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone) (n = 26, CR 61.5%, PR 34.0%); Madison–Wisconsin (MW) (n = 12, CR 66.7%, PR 25.0%). Overall median survival was 373 days (range, 20–2015 days) (COP 484 days [range, 20–980 days]; MW 211 days [range, 24–2015 days] [P = 0.892]). Cats achieving CR survived longer (980 days vs 42 days for PR; P = 0.032). Age, breed, sex, location (mediastinal vs mediastinal plus other sites), retroviral status and glucocorticoid pretreatment did not affect response or survival. Feline mediastinal lymphoma cases frequently responded to chemotherapy with durable survival times, particularly in cats achieving CR. The prevalence of FeLV-antigenaemic cats was low; males and young Siamese cats appeared to be over-represented.

Introduction

Lymphoma is the most commonly diagnosed tumour in cats, accounting for 30% of all feline malignancies.1–7 Retroviral infections have long been associated with development of feline lymphoma,7–11 and studies conducted in the 1980s, before widespread vaccination for feline leukaemia virus (FeLV), indicated that approximately 70% of cats with lymphoma were FeLV antigenaemic5,12 and tended to be younger in age.11,12 In the pre-vaccination era, mediastinal lymphoma, (involving the thymus, mediastinal and sternal lymph nodes) was a common anatomical presentation, accounting for 20–40% of cases in the USA, 13 10–50% of cases in the UK 13 and 70% of cases in Japan. 14 The introduction of FeLV vaccination in 1985 has resulted in a significant decrease in the prevalence of FeLV infection among the feline population 15 and, concurrently, a decrease in the proportion of feline lymphoma cases presenting with the mediastinal form has been observed. 15 Recent studies have reported the mediastinal form to have constituted <15% of feline lymphoma cases in the USA in 1998 and 2005,5,15 and approximately 25% of cases in Australia in 1997. 16 Genetic factors may also play a role in the development of mediastinal lymphoma, with young Siamese and Siamese-associated breeds appearing to be predisposed.13,15–18,21

Different chemotherapy regimens have been described for feline lymphoma, with variable results.5,14,19–21 The retrospective nature of most of the previous investigations, combined with the lack of homogeneity regarding anatomical subtype, clinical staging information, retroviral status, histopathological grade and sub-classification or chemotherapy protocol used, has resulted in the absence of consensus regarding the gold standard treatment or treatments for different forms of feline lymphoma. Taylor et al 22 recently evaluated response to a COP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone) chemotherapy protocol and the Madison–Wisconsin (MW) (doxorubicin, vincristine, cyclophosphamide and prednisone) chemotherapy protocol in a large group of cats with extranodal lymphoma in UK. 22 The results of this study indicated a high response rate to chemotherapy (overall response to MW and COP protocols combined: 87%; medium survival time [MST] of cats receiving MW and COP: 171 days and 112 days, respectively). However, cats with mediastinal lymphoma were not included in that study and to our knowledge, assessment of treatment outcomes in a large cohort of cats with this anatomical presentation has not been reported previously. The purpose of the current study was to describe the signalment, retroviral status, response to chemotherapy and survival time in a large group of cats with mediastinal lymphoma in the UK. In addition, patient characteristics were assessed to identify prognostic indicators.

Materials and methods

This was a retrospective multi-institutional study. The medical records of client-owned cats diagnosed with mediastinal lymphoma at five veterinary referral hospitals in the UK (Royal Veterinary College, University of Bristol, University of Edinburgh, University of Cambridge and Animal Health Trust) were reviewed. Cases were recruited from 1998 to 2010. Data regarding, age, breed, sex, presenting clinical signs, tumour anatomical location (mediastinum only or mediastinum plus other sites), retroviral status, diagnostic tests, chemotherapy protocol, response to chemotherapy and survival were recorded. Inclusion criteria included were a cytological or histopathological diagnosis of lymphoma and presenting clinical signs associated with a mediastinal mass (dyspnoea, tachypnoea or reduced thoracic compression).

FeLV and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) testing was performed using the preferred method at each institution. The method of retrovirus testing was not always specified in the medical records, but it was assumed that enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-based methods were used to assess the presence of FeLV antigenaemia and the presence of FIV antibodies. Regarding anatomical location of the lymphoma, cats were divided in two groups: mediastinum (including tumour affecting thymus, mediastinal and sternal lymph nodes) and mediastinum plus other sites, typically based on clinical or imaging findings.

Cats were excluded from the response and survival assessment if they had received chemotherapy prior to referral (with the exception of corticosteroids), if they received no treatment, if they were treated with a chemotherapy protocol other than COP or a MW protocol as first line, or if medical records were incomplete.

As this was a retrospective study, the response to treatment was reported as recorded in the medical record by the attending clinician, who determined response to chemotherapy based on assessment of tumour size following thoracic radiographs and/or thoracic ultrasound. Time intervals between restaging procedures varied and patient re-evaluations were performed at each clinician’s discretion. Response was considered complete (CR) if there was 100% reduction in size of all measurable disease and partial (PR) if there was ⩾50% but <100% reduction in size of all measurable disease. No change in size, ⩽50% reduction in size and increase in size of all measurable disease were classified as no response (NR).

Statistical analysis

CR and PR rates were defined as the number of cats achieving CR or PR expressed as a percentage of the total number of cats treated. Only cats treated with a COP chemotherapy protocol or the MW protocol were included in the response data and survival analysis. Factors analysed for effect on treatment response were breed, age, sex, retroviral status, tumour location (mediastinal versus mediastinal plus other sites), chemotherapy treatment protocol and whether the cat was pretreated with corticosteroids. For statistical analysis, cats were divided into three groups based on age at presentation (<3 years, 3–6 years and >6 years). Breed was analysed as crossbred versus purebred. The Kaplan–Meier product limit analysis and the log rank test were used for survival analysis. As the cause of death could not be clearly established in all cases, survival time was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death from any cause. Survival time was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death from any cause. Cats were censored if they were alive at the end of the study, or on the date they were last known to be alive, if lost to follow-up. The χ2 or Fisher’s exact test was used for comparative analysis of groups. The log rank test was used to evaluate the following variables for influence on survival times: age, breed, sex, retroviral status, anatomical presentation (mediastinum versus mediastinum plus other sites), previous treatment with corticosteroids and response to chemotherapy. A P value <0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed by SPSS statistics software, version 18.0.

Results

Fifty-five cats met the inclusion criteria for the study. Patient characteristics are summarised in Table 1. The median age at diagnosis was 3 years (range, 6 months to 12 years). There appeared to be a bimodal age distribution with a peak at 1 year, and smaller peak at 8 years (Figure 1). All affected Siamese cats were less than 5 years old and they were significantly younger than other breeds (P = 0.03) (Figure 1). The cats included 23 domestic shorthairs (41.8%), 12 Siamese (21.8%), eight domestic longhairs (14.5%), three Persians (5%), two Orientals (4%), two Abyssinians (4%), and one each of Birman, Russian Blue, Bombay and Devon Rex. There were 13 spayed females (24%), 40 neutered males (73%) and two intact males (3%). The male to female ratio was 3.2:1.0.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of 55 cats with mediastinal lymphoma

| Variable | Category | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| 0–3 | 25 | 45.40 | |

| 3–6 | 10 | 18.20 | |

| ⩾6 | 20 | 36.40 | |

| Breed | |||

| DSH | 23 | 41.80 | |

| Siamese | 12 | 21.80 | |

| DLH | 8 | 14.50 | |

| Persian | 3 | 5.00 | |

| Oriental | 2 | 4.00 | |

| Abyssinian | 2 | 4.00 | |

| Others | 5 | 9.90 | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 13 | 24.00 | |

| Male | 42 | 76.00 | |

| Tumour anatomical location | |||

| Mediastinum | 42 | 76.00 | |

| Mediastinum + other sites | 13 | 24.00 | |

| FeLV/FIV status | |||

| FeLV antigen-positive | 5 | 9.00 | |

| FIV antibody-positive | 2 | 3.60 | |

| FeLV antigen- and FIV antibody-negative | 48 | 87.40 | |

| Pretreatment with corticosteroids | |||

| Yes | 14 | 25.45 | |

| No | 41 | 74.55 |

FeLV = feline leukaemia virus; FIV = feline immunodeficiency virus; DSH = domestic shorthair; DLH = domestic longhair

Figure 1.

Age distribution of 55 cats with mediastinal lymphoma. Red bars represent Siamese; blue bars represent all other breeds together

Presenting clinical complaints were dyspnoea (n = 43; 78%), inappetence (n = 18; 32%) regurgitation (n = 7; 13%), cough (n = 4; 7%) and pyrexia (n = 1; 2%). Twenty-eight cats (51%) had pleural effusion. Median duration of clinical signs before presentation was 11.5 days (range, 1–70 days). In 40 cats, a diagnosis of lymphoma was achieved following cytological evaluation of pleural effusion and/or fine-needle aspirates of a mediastinal mass. In the remaining 15 cats, diagnosis was reached through histopathological examination of tumour biopsies. Investigations at diagnosis included complete blood cell count and serum biochemistry profile in all 55 cats, thoracic radiographs alone in 18 cats, thoracic ultrasound alone in 20 cats, and both thoracic radiographs and thoracic ultrasound in 17 cats. Abdominal ultrasonography was performed in six cats; and two cats underwent bone marrow aspiration. None of the cats was leukaemic at presentation. In the two cats in which bone marrow aspiration was performed, cytological evaluation of these samples did not reveal lymphoma infiltration. Thirteen cats (24%) had documented tumoural involvement of the mediastinum plus other sites (including eight cats with peripheral lymph node involvement, two with lung involvement, one with mesenteric lymph node involvement, one with renal involvement and one with hepatic involvement). Tumour location for the remaining 42 cats was recorded only in the mediastinum; however, staging was not complete in most cases.

Forty-eight cats (87%) tested negative for FeLV antigenaemia and for FIV antibodies, five (9%) tested positive for FeLV antigenaemia and two (3.6%) tested positive for FIV antibodies. No cats tested positive for both FIV antigenaemia and FeLV antibodies. All Siamese cats tested negative for FeLV antigenaemia and FIV antibodies. Fourteen cats (25.5%) had received corticosteroids prior to commencing a multi-drug chemotherapy protocol, but the duration of treatment was not recorded.

Complete records, for evaluation of treatment response and survival analysis, were available in 38 cats. Reasons for exclusion from response and survival analysis were no pursuit of treatment (n = 6) and incomplete medical records (n = 11). Twenty-six cats received a COP protocol and 12 cats received the MW protocol. The overall response rate to COP and MW chemotherapy protocols combined was 94.7% (63.1 % CR, 31.6% PR and 5.3% NR). Of the cats receiving a COP protocol, 61.5% achieved a CR, 34.0% a PR and 4.5% experienced either stable or progressive disease. The overall response rate for COP was 95.5%. Of the cats receiving the MW protocol, 66.7% achieved a CR, 25.0% a PR and 8.3% did not respond. The overall response rate for the MW protocol was 91.7% (Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference in response rate and proportion of PR and CR between the two protocols. Age, breed, sex, retroviral status, tumour location (mediastinal versus mediastinal plus other sites) and pretreatment with corticosteroids were not significantly associated with treatment response (Table 3).

Table 2.

Summary of remission rates achieved by 38 cats treated either with a COP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone) or a Madison–Wisconsin protocol

| Protocol | Number of cats (n = 38) |

Complete response rate number (%) | Partial response rate number (%) |

No response number (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COP | 26 | 16 (61.5) | 9 (34.0) | 1 (4.5) |

| Madison–Wisconsin | 12 | 8 (66.7) | 3 (25.0) | 1 (8.3) |

Table 3.

Results of univariate analysis of patient variables for treatment response and survival

| Variable | Influence of variable on response (P value) | Influence of variable on survival (P value) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| Breed | 0.23 | 0.32 |

| Gender | 0.17 | 0.22 |

| Tumour anatomical location | 0.33 | 0.57 |

| FeLV status | 0.14 | 0.09 |

| FIV status | 0.22 | 0.18 |

| Pretreatment with corticosteroids | 0.52 | 0.75 |

| Type of response (CR vs PR) | NA | 0.03 |

| Type of protocol (COP vs MW) | 0.26 | 0.89 |

FeLV = feline leukaemia virus; FIV = feline immunodeficiency virus; CR = complete response; PR = partial response; COP = cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone; MW = Madison–Wisconsin; NA = not applicable

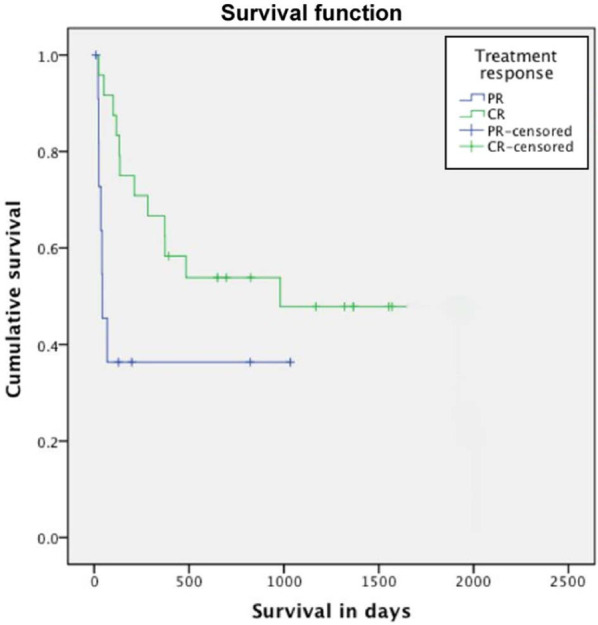

At the end of the study, 23/38 treated cats had died or had been euthanased, three cats were still alive and 12 were lost to follow-up. Based on data available cause of death or euthanasia was progression of lymphoma in 15 cats and causes considered unlikely related to lymphoma in five cats. In the remaining three cats the cause of death could not be clearly determined. For all cats median follow-up time was 247 days (range, 5–2015 days) for cats lost to follow-up was 825 days (range, 8–1570 days) and for those cats censored as still alive was 696 days (range, 392–1320 days). The overall MST was 373 days (range, 20–2015 days) (Figure 2). The MST was not statistically different (P = 0.892) in cats receiving a COP protocol (MST: 484 days; range, 20–980 days) and those receiving the MW protocol (MST: 211 days; range, 24–2015 days) (Figure 3). When considering both protocols together, cats achieving a CR survived significantly longer than those achieving a PR (median 980 days and 42 days, respectively; P = 0.032) (Figure 4). Age, breed, sex, retroviral status, anatomical location (mediastinum versus mediastinum plus other sites) and pretreatment with corticosteroids did not affect the survival times (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve showing the overall survival of 38 cats with mediastinal lymphoma treated with a COP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone) or a Madison–Wisconsin protocol. Median survival time was 373 days (range, 20–2015 days)

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curve showing survival of 38 cats with mediastinal lymphoma stratified according to treatment protocol received. The blue line indicates cats that received a COP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone) protocol; the green line indicates cats that received Madison–Wisconsin protocol. There was no signficant difference in survival time between treatment protocols received (P = 0.216)

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier curve showing survival curves stratified according to type of response.Those patients achieving a complete response (CR) had a significantly longer survival time than those achieving a partial response (PR) (P = 0.032)

Discussion

Previous studies have indicated that mediastinal lymphoma occurs most frequently in young FeLV-antigenaemic cats.5,11,12 This observation has been made based on epidemiological data obtained from reports in the 1980s, when FeLV antigenaemia prevalence among cats with lymphoma was estimated to be around 70%. However, more recent studies have suggested that FeLV vaccination and increased detection of antigenaemic cats have shifted the demographics of lymphoma from affecting young, FeLV-positive cats to more frequently affecting older, FeLV-negative cats.15,21,22 A study conducted in 2002 in the Netherlands, a country reported to have the lowest prevalence of FeLV antigenaemia among healthy cats in the world, indicated that 18.8% (4/22) cats with mediastinal lymphoma were FeLV-antigenaemic. 21 In the present study, in contrast to most previous reports, only a small proportion (9%) of cats with mediastinal lymphoma tested positive for FeLV antigenaemia. The method of FeLV testing was not specified in all the case records, but it was considered likely that the FeLV status was attributed following a serum antigen test (ELISA). Virus isolation, immunofluorescence or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was not performed to our knowledge. Weiss et al 23 showed that, in archived tissues, 80% of feline T cell lymphomas and 60% of feline B cell lymphomas (affecting various sites) contained FeLV provirus DNA using PCR, while only 21% of T cell and 11% of B cell lymphomas expressed FeLV antigen by immunohistochemistry. Concurrent FeLV antigenaemia status in blood was not assessed. Integration of FeLV provirus DNA may play a role in lymphoma pathogenesis in such cases. However, in a different study of 61 cats tested to be FeLV-negative by ELISA, Stutzer et al 24 failed to detect any FeLV provirus by PCR in various tissues (lymphoma tissue [n = 57], blood [n = 17] or bone marrow [n = 10]), suggesting that latent FeLV infection may be uncommon in cats testing negative for FeLV antigenaemia. The apparently conflicting results of these two studies might be owing to differences in the two populations of cats tested; alternatively, the PCR methodology may not have been equivalent and it is possible that false-positive or false-negative results may have occurred. In the current study, although the prevalence of FeLV antigenaemia was low at 9%, the presence of FeLV provirus in tissues was not investigated and the true presence of FeLV virus may have been underestimated in these cats. The role of FeLV in mediastinal lymphoma pathogenesis requires further investigation.

The median age of cats in the present study was 3 years, which is comparable to previous reports for cats with mediastinal lymphoma.2,16 The bimodal distribution of age, reported in previous studies for cats with lymphoma at various anatomical sites,17,21,25 found confirmation in the present study. Interestingly, almost 50% of all cats aged ⩽3 years were Siamese. All Siamese cats, however, tested negative for FeLV antigen, suggesting that FeLV viraemia is not a likely explanation for this peculiar age distribution in this breed, and the reason remains unknown. Although Siamese cats appeared to be over-represented in the current study, the prevalence of this breed in the general cat population at each referral institution was not known, meaning that firm conclusions about breed predisposition could not be made. However, as previously reported,15,16,21 Siamese cats seemed to be commonly affected and were significantly younger than other breeds, suggesting that genetic factors, rather than FeLV viraemia, may play an important role in the development of mediastinal lymphoma in this breed. In addition, cats included in the current study were mostly males and, if it was assumed that the sex distribution between males and females was equal in the hospital population, the results might suggest an over-representation of males. However, figures regarding the proportion of male and female cats presenting to each referral institution were not available, and results should be interpreted with caution.

The overall combined response rate to COP and MW chemotherapy protocols was high (94.7%), indicating that treatment of cats with mediastinal lymphoma can be rewarding. The CR rate receiving a COP protocol (61.5%) in the current study was lower than previously reported in cats with mediastinal lymphoma (81.8% by Teske et al 21 and 92% in the study by Cotter et al 18 ) and significantly better than that achieved with the use of a VCM (vincristine, cyclophosphamide and methotrexate) protocol (45%). 26 The CR rate achieved with the MW protocol was 66.7%. Response rates to the MW protocol have not been reported for mediastinal lymphoma previously, but the current result compares favourably with a rate of 47% achieved when treating various anatomical forms of feline lymphoma. 20 No difference was found in CR rate or survival between cats receiving a COP protocol and those receiving the MW protocol, suggesting that the use of this doxorubicin-containing protocol in cats with mediastinal lymphoma may not provide additional benefits over a COP protocol alone. However, the smaller number of cases receiving the MW protocol (12 cats) in comparison with those receiving the COP protocol (26 cats) may have reduced the probability of detecting a difference between the two protocols. A prospective randomised study, including a larger group of cats with standardised complete staging, would be required to confirm this finding.

The overall MST in treated cats was 373 days, which, to our knowledge, is the longest MST reported for feline mediastinal lymphoma. Previous studies identified a MST of 262 days in 22 cats with mediastinal lymphoma, 18% of which were FeLV-positive 21 and survival times of 2–3 months for FeLV-positive cats.5,26 Of all the variables analysed, only the type of response was found to affect the survival outcome significantly. As previously reported, cats achieving a CR survived much longer than those achieving a PR. However, response to therapy can only be evaluated after treatment is started, and this may limit the value of this parameter as a true prognostic indicator at the outset. Surprisingly, and in contrast with previous reports,2,5 FeLV infection was not found to influence the survival in a negative manner. A possible explanation for this finding could be the small number of cases in the current study, which may have lowered the probability of detecting significant differences, if present. Pretreatment with corticosteroids was found not to affect the treatment response and survival, in accordance with previous reports.22,27 However, information regarding the duration and dose of corticosteroid therapy was not recorded, which may have influenced the results.

The retrospective and multi-institutional nature of this study is a major limitation. When analysing and comparing response rates and survival durations, it is important to appreciate that, although similar drug doses and frequency were used, heterogeneity in chemotherapy protocols existed among and within contributing institutions. The method of diagnosis varied, and cytology and histopathology results were not reviewed. In addition, clinical staging and assessment of response were not always performed in a complete and standardised manner and, thus, conclusions drawn from these results should be interpreted accordingly. Remission durations and progression-free intervals were not evaluated owing to the retrospective nature of this report, and the inability to collect data regarding dates of relapses and subsequent types and length of rescue protocols may have affected survival results.

Conclusions

A large percentage of cats with mediastinal lymphoma responded to chemotherapy and the MST exceeded 1 year, indicating that cats with mediastinal lymphoma can experience prolonged survival and may have a better prognosis than previously reported. No survival advantage was found with the use of a MW protocol in comparison with a COP protocol, and the prevalence of FeLV antigenaemic cases in this study was low compared with other reports of cats with mediastinal lymphoma. Male cats were more commonly affected than females. Young, Siamese cats appeared to be over-represented, indicating that genetic factors might play an important role in the aetiopathogenesis of lymphoma in this breed.

Footnotes

The authors do not have any potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Accepted: 20 November 2013

References

- 1. Malik R, Gabor LJ, Foster SF, et al. Therapy for Australian cats with lymphosarcoma. Aust Vet J 2001; 79: 808–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mooney SC, Hayes AA, MacEwen EG, et al. Treatment and prognostic factors in lymphoma in cats: 103 cases (1977–1981). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1989; 194: 696–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mooney SC, Hayes AA, Matus RE, et al. Renal lymphoma in cats: 28 cases (1977–1984). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1987; 191: 1473–1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Podell M, DiBartola SP, Rosol TJ. Polycystic kidney disease and renal lymphoma in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1992; 201: 906–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vail DM, Moore AS, Ogilvie GK, et al. Feline lymphoma (145 cases): proliferation indices, cluster of differentiation 3 immunoreactivity, and their association with prognosis in 90 cats. J Vet Intern Med 1998; 12: 349–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mahony OM, Moore AS, Cotter SM, et al. Alimentary lymphoma in cats: 28 cases (1988–1993). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1995; 207: 1593–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lane SB, Kornegay JN, Duncan JR, et al. Feline spinal lymphosarcoma: a retrospective evaluation of 23 cats. J Vet Intern Med 1994; 8: 99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Endo Y, Cho KW, Nishigaki K, et al. Molecular characteristics of malignant lymphomas in cats naturally infected with feline immunodeficiency virus. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 1997; 57: 153–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gabor LJ, Jackson ML, Trask B, et al. Feline leukaemia virus status of Australian cats with lymphosarcoma. Aust Vet J 2001; 79: 476–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rezanka LJ, Rojko JL, Neil JC. Feline leukemia virus: pathogenesis of neoplastic disease. Cancer Invest 1992; 10: 371–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rojko JL, Kociba GJ, Abkowitz JL, et al. Feline lymphomas: immunological and cytochemical characterization. Cancer Res 1989; 49: 345–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guillermo Couto C. What is new on feline lymphoma? J Feline Med Surg 2001; 3: 171–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gruffydd-Jones TJ, Gaskell CJ, Gibbs C. Clinical and radiological features of anterior mediastinal lymphosarcoma in the cat: a review of 30 cases. Vet Rec 1979; 104: 304–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Takahashi R, Goto N, Ishii H, et al. Pathological observations of natural cases of feline lymphosarcomatosis. Nihon Juigaku Zasshi 1974; 36: 163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Louwerens M, London CA, Pedersen NC, et al. Feline lymphoma in the post-feline leukemia virus era. J Vet Intern Med 2005; 19: 329–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Court EA, Watson AD, Peaston AE. Retrospective study of 60 cases of feline lymphosarcoma. Aust Vet J 1997; 75: 424–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gabor LJ, Malik R, Canfield PJ. Clinical and anatomical features of lymphosarcoma in 118 cats. Aust Vet J 1998; 76: 725–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cotter SM, Hardy WD, Jr, Essex M. Association of feline leukemia virus with lymphosarcoma and other disorders in the cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1975; 166: 449–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kristal O, Lana SE, Ogilvie GK, et al. Single agent chemotherapy with doxorubicin for feline lymphoma: a retrospective study of 19 cases (1994–1997). J Vet Intern Med 2001; 15: 125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Milner RJ, Peyton J, Cooke K, et al. Response rates and survival times for cats with lymphoma treated with the University of Wisconsin-Madison chemotherapy protocol: 38 cases (1996–2003). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2005; 227: 1118–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Teske E, van Straten G, van Noort R, et al. Chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisolone (COP) in cats with malignant lymphoma: new results with an old protocol. J Vet Intern Med 2002; 16: 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Taylor SS, Goodfellow MR, Browne WJ, et al. Feline extranodal lymphoma: response to chemotherapy and survival in 110 cats. J Small Anim Pract 2009; 50: 584–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weiss A, Klopfleish R, Gruber AD. Prevalence of feline leukaemia provirus DNA in feline lymphomas. J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12: 929–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stutzer B, Simon K, Lutz H, et al. Incidence of persistent viraemia and latent feline leukaemia virus infection in cats with lymphoma. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 81–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schneider R. Comparison of age- and sex-specific incidence rate patterns of the leukemia complex in the cat and the dog. J Natl Cancer Inst 1983; 70: 971–977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jeglum KA, Whereat A, Young K. Chemotherapy of lymphoma in 75 cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1987; 190: 174–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Simon D, Eberle N, Laacke-Singer L, et al. Combination chemotherapy in feline lymphoma: treatment outcome, tolerability, and duration in 23 cats. J Vet Intern Med 2008; 22: 394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]