Abstract

We have attempted to develop an anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) lipopeptide vaccine with several HIV-specific long peptides modified by C-terminal addition of a single palmitoyl chain. A mixture of six lipopeptides derived from regulatory or structural HIV-1 proteins (Nef, Gag, and Env) was prepared. A phase I study was conducted to evaluate immunogenicity and tolerance in lipopeptide vaccination of HIV-1-seronegative volunteers given three injections of either 100, 250, or 500 μg of each lipopeptide, with or without immunoadjuvant (QS21). This report analyzes in detail B- and T-cell responses induced by vaccination. The lipopeptide vaccine elicited strong and multiepitopic B- and T-cell responses. Vaccinated subjects produced specific immunoglobulin G antibodies that recognized the Nef and Gag proteins. After the third injection, helper CD4+-T-cell responses as well as specific cytotoxic CD8+ T cells were also obtained. These CD8+ T cells were able to recognize naturally processed viral proteins. Finally, specific gamma interferon-secreting CD8+ T cells were also detected ex vivo.

Despite the decrease in mortality among humans infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) due to new antiretroviral agents, development of an effective vaccine to prevent HIV infection remains a high priority, since the vast majority of individuals do not have access to these new treatments and new infections continue to occur.

Many candidate vaccines have been tested in experimental models over the last 10 years, but to date potent protective immunity has been obtained only with attenuated live simian immunodeficiency virus in macaques (12, 14). Although safety issues remain a major concern when using attenuated live vaccines, this study may help to clarify how protective immunity against AIDS is induced. Most of the candidate HIV-1 vaccines which have undergone clinical trials have been based on envelope subunit vaccines. The results of these trials have indicated that such vaccines did not induce a neutralizing antibody response that cross-reacted with primary HIV-1 isolates. Moreover, these envelope vaccines are ineffective in eliciting a CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) response (13). Vaccines using live recombinant poxvirus constructs are more potent CTL immunogens, and human phase I studies have investigated immune responses to canarypox clade-B-based ALVAC–HIV-1 recombinants (2, 9). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in some volunteers demonstrated CTL activity, but their responses remained limited and cross-reactive CTL activity was detected in only a few of the responders. Moreover, some individuals became infected with HIV-1 despite vaccination with the recombinant HIV gp120 subunit (4). On the other hand, CD4+ T cells play a pivotal role in the development of the immune response by secreting various cytokines involved in the induction and maturation of humoral and cellular immunity. Therefore, it would be critical to evaluate the Th1-Th2 balance and to quantify HIV-specific CD4+ T cells obtained after vaccination.

We have developed a new HIV-1 vaccine based on lipopeptides. Several experiments have shown that cellular and humoral immune responses can be induced in mice (22, 29), in primates (1, 24), and in humans (20, 33) by means of simple lipopeptide vaccines. The frequency and duration of the CTL response are directly influenced by the presence of potent CD4+ epitopes (20, 23, 27, 33). We therefore constructed an anti-HIV lipopeptide vaccine which consisted of a total of six long amino acid sequences derived from regulatory or structural HIV-1 proteins (Nef, Gag, and Env), containing altogether 50 to 60 different major histocompatibility complex class I-specific CTL epitopes. These epitopes have been identified in Nef, Gag, and Env proteins by the CTL responses of naturally infected patients or from the structural characteristics of major histocompatibility complex-peptide interactions. The CTL epitopes corresponded to the total of the epitopes that we were able to identify in the six long peptides. Some sequences of these HIV epitopes may be found in the NIH molecular database and in two recent publications (6, 7; HIV Molecular Immunology Database [http://hiv-web.lane.gov/immuno/index.html]). Other sequences have been defined by a biochemical assay (3, 5). These amino acid sequences also contained CD4+ T-cell and B-cell epitopes. The six sequences were modified in the C-terminal position by adding a palmitoyl-lysylamide group and formulated as lyophilized mixed micelles (15).

In the present work, we have conducted a phase I study to evaluate the immunogenicity and tolerance of our lipopeptide vaccine in HIV-1-seronegative volunteers who were given three injections of either 100, 250, or 500 μg of each lipopeptide with or without an adjuvant (QS21). Strong and multiepitopic B- and T-cell responses were obtained.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sequences and synthesis of lipopeptides.

The following three lipopeptides obtained from HIV-LAI Nef proteins were synthesized: L-N1 (Nef amino acids [aa] 66 to 97), L-N2 (Nef aa 117 to 147), and L-N3 (Nef aa 182 to 205). Two lipopeptides derived from HIV-LAI Gag proteins were also synthesized, L-G1 (Gag aa 183 to 214) and L-G2 (Gag aa 253 to 284). Finally, we prepared one lipopeptide derived from an V3-ENV gp120 consensus sequence that is also found in the HIV-BX08 strain, L-E (Env aa 303 to 335). Each lipopeptide was synthetized by BACHEM Feinchemikalien (Bubendorf, Switzerland). The lipopeptides were formulated as mixed micelles, solubilized in 80% acetic acid at 20 mg/ml, mixed, and subjected to sterilizing filtration under GMP conditions (Sterilyo, Saint-Amand-les-Eaux, France). The solution was distributed into individual vials, lyophilized, and stored under nitrogen. The water solubility of the vaccine doses was confirmed after reconstitution with 1.3 ml of water or 5% isotonic glucose solution, yielding a slightly opalescent solution (pH 4.93). The lipopeptide components, their impurity profiles, and the vaccine candidate were analyzed by high-pressure liquid chromatography, Edman sequencing, electrospray mass spectrometry, and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. The preclinical safety of the product was assessed by extensive toxicological studies (15). The amino acid sequences, molecular weights, and numbers of the six lipopeptides are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Amino acid sequences, molecular weights, and numbers of the six selected lipopeptides

| Lipopeptidea | Long peptide | Sequenceb | MW | No. of amino acids |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-N1 | N1 (Nef 66 to 97) | VGFPVTPQVPLRPMTYKAAVDLSHFLKEKGGL K(Palm)-NH2 | 3,862.8 | 32(+1) |

| L-N2 | N2 (Nef 117 to 147) | TQGYFPDWQNYTPGPGVRYPLTFGWCYKLVP K(Palm)-NH2 | 4,017.8 | 31(+1) |

| L-N3 | N3 (Nef 182 to 205) | EWRFDSRLAFHHVARELHPEYFKN K(Palm)-NH2 | 3,451.1 | 24(+1) |

| L-G1 | G1 (Gag 183 to 214) | DLNTMLNTVGGHQAAMQMLKETINEEAAEWDR K(Palm)-NH2 | 3,983.7 | 32(+1) |

| L-G2 | G2 (Gag 253 to 284) | NPPIPVGEIYKRWIILGLNKIVRMYSPTSILD K(Palm)-NH2 | 4,063.1 | 32(+1) |

| L-E | E (Env 303 to 335) | TRPNNNTRKSIHIGPGRAFYATGEIIGDIRQAH K(Palm)-NH2 | 4,027.7 | 33(+1) |

The names of lipopeptides and long peptides are obtained from origin of the HIV-1 gene (Nef, Gag, and Env). Amino acid positions are identified with respect to the LAI sequence for N1, N2, N3, G1, and G2 and the BX08 sequence for E.

The sequences were modified in the C-terminal position by a palmitoyl-lysylamide group [K(Palm)-NH2.

Long and short peptides.

The following long peptides corresponding to the lipopeptide immunogens were also synthesized in one of our laboratories (UMR 8525 CNRS, Lille, France): N1 (Nef aa 66 to 97), N2 (Nef aa 117 to 147), N3 (Nef aa 182 to 205), G1 (Gag aa 183 to 214), G2 (Gag aa 253 to 284), and E (Env aa 303 to 335). Short peptides overlapping the lipopeptide sequences and known to be minimal CTL epitopes were synthesized by Neosystem (Strasbourg, France). We used Nef 121 to 128, Nef 137 to 145, Nef 184 to 191, and Nef 195 to 202 (HLA-A1 restricted); Nef 136 to 145, Nef 190 to 198, Gag 183 and 191, and M 58 to 66 (HLA-A2 restricted); Nef 73 to 82, Nef 84 to 92, and EBN 416 to 424 (HLA-A11 restricted); Nef 90 to 97 and Nef 182 to 189 (HLA-B8 restricted); Nef 134 to 141 and Gag 263 to 272 (HLA-B27 restricted); and Nef 135 to 143 (HLA-B18 restricted). The 16 CTL epitopes mentioned above cover the range of HLA class I alleles present in the vaccinated subjects tested by an enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay (see Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Ex vivo specific IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cellsa

| Peptide incubated with PBMCb | No. of IFN-γ SFCc/106 cells:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V4.6 (A2/68 B39/53)

|

V4.17 (A1/30 B51/07)

|

V4.18 (A2/11 B44/60)

|

V4.5 (QS21) (A2/11 B18/27)

|

V4.19 (QS21) (A2/24 B51/44)

|

V4.21 (QS21) (A1/34 B8/51)

|

|||||||

| W0 | W20 | W0 | W20 | W0 | W20 | W0 | W20 | W0 | W20 | W0 | W20 | |

| HLA-A1 | ||||||||||||

| Nef 121 to 128 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 41 | ||||||||

| Nef 137 to 145 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||

| Nef 184 to 191 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 26 | ||||||||

| Nef 195 to 202 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| HLA-A2 | ||||||||||||

| Nef 136 to 145 | 6 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 32 | ||||

| Nef 190 to 198 | 5 | 62 | NDd | ND | 4 | 16 | 0 | 6 | ||||

| Gag 183 to 191 | 10 | 22 | ND | ND | 2 | 16 | 0 | 24 | ||||

| M 58–66 | 30 | 34 | 150 | 100 | 7 | 10 | 66 | 52 | ||||

| HLA-A11 | ||||||||||||

| Nef 73 to 82 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 0 | ND | ND | ||||||

| Nef 84 to 92 | 0 | 55 | ND | ND | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| EBN 416 to 424 | 500 | 500 | 66 | 63 | ND | ND | ||||||

| HLA-B8 | ||||||||||||

| Nef 90 to 97 | 1 | 51 | ||||||||||

| Nef 182 to 189 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 26 | ||||||||

| HLA-B27 | ||||||||||||

| Nef 134 to 141 | 2 | 14 | ||||||||||

| Gag 263 to 272 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||

| HLA-B18 | ||||||||||||

| Nef 135 to 143 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||

Ex vivo ELISPOT assay was carried out with PBMC collected from volunteers at W0 and W20. The class I HLA haplotype was identified in each volunteer.

Various CD8+ epitopic peptides (10 μg/ml) from HIV-1, EBV (EBN 416 to 424, HLA-A11) and influenza virus (M 58 to 66, HLA-A2) were incubated for 20 h with 2 × 105 PBMC.

Mean values of IFN-γ spot-forming cells (SFC) for 106 cells are shown. Boldface type indicates positive results.

ND, not done.

Immunization protocol and study design.

HIV-negative volunteers were selected by the National French Agency for AIDS Research (ANRS). Written consent was obtained from each volunteer, and the nature and consequences of the studies were also explained. The volunteers enrolled in the Vac 04 ANRS study were chosen to belong to non-HIV-exposed groups. Moreover, a classic clinical investigation was performed to determine the HIV serology of the volunteers. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and Western blots were performed on the sera of all the volunteers before immunization. Two different ELISA kits were used: one from Abbott (HIV-1/HIV-2 EIA Third-Generation Plus) and one from Vironostika (HIV Uni-form II Ag/Ab; Organon Teknika, Durham, N.C.). The HIV-1-negative status was also defined by Western blotting with the Cambridge Biotech (Worcester, Mass.) HIV-1 Western blot kit. Finally, serology to HIV-1 and HIV-2 was determined by using the HIV blot 2.2 kit (Genelabs Diagnostics, Singapore Science Park, Singapore).

The phase I clinical trial was defined as a dose escalation study starting with 100, 250 μg, and 500 μg of the six lipopeptides to determine the clinical tolerance. Because the low dose was well tolerated, the vaccine trial was continued with the high dose. The QS21 adjuvant was added to determine the influence of this adjuvant on induction of the immune response by lipopeptides. Volunteers were immunized by intramuscular injection of a mixture of six lipopeptides with or without QS21 adjuvant. All volunteers were immunized three times with the six lipopeptides at 0, 4, and 16 weeks. The dose of lipopeptides injected varied from one subject to another. Volunteer V4.6 was given 250 μg of each lipopeptide, whereas V4.16, V4.17, V4.18, V4.23, and V4.28 were immunized with 500 μg of each of the six lipopeptides. On the other hand, volunteers V4.5, V4.1, V4.19, V4.21, V4.32, and V4.34 were immunized with the six lipopeptides in QS21 adjuvant. V4.5 received 100 μg of each lipopeptide, and the other five volunteers received 500 μg of each lipopeptide. Blood samples were collected prior to immunization (week 0) and during week 20, after the third immunization. PBMC and serum were separated by standard methods and frozen. The complete results obtained with 12 volunteers are presented in this report.

Anti-HIV peptide IgG antibodies detected by ELISA.

Polystyrene plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with 5 μg of long peptides (N1, N2, N3, G1, G2, and E) per ml. Diluted (1/100) sera were detected with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-human immunoglobulin G (IgG) (1/5,000; Sigma). Phosphatase activity was measured with 4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate as the substrate (Sigma), and fluorescence was read at 360/460 nm in a Victor multilabel counter (Wallac).

The baseline value differed for each long peptide and was obtained for each serum sample prior to immunization. In the majority of cases, the baseline ranges (in fluorescence units) were as follows: N1, 2 × 103 to 23 × 103; N2, 2 × 103 to 15 × 103; N3, 2 × 103 to 23 × 103; G1, 2 × 103 to 21 × 103; G2, 2 × 103 to 19 × 103; and E, 2 × 103 to 36 × 103; and in 10 to 20% of cases the baseline was 40 × 103 fluorescence units. Because we looked for induction of humoral responses after immunization, we took into account the values that gave a fluorescence value at least twice the baseline. The sera taken from each volunteer prior to and after immunization were tested three times by ELISA in independent experiments.

Anti-Nef and anti-Gag antibodies detected by Western blotting.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was carried out on 10% acrylamide gels (Bio-Rad, Ivry-sur-Seine, France) as already described (11). The Nef protein (produced by Escherichia coli) was visible as a 25- to 27-kDa doublet in SDS-PAGE. Immunoblotting was carried out for Nef protein, using human sera diluted 1/100. Horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-human IgG (The Binding Site, Birmingham, United Kingdom) and a chemiluminescent substrate (Luminol, Amersham, France) were used to detect the reaction. Anti-Gag antibodies were detected with a commercial kit (New Lav Blot I; Sanofi, Diagnostics Pasteur).

Anti-HIV peptide proliferative T-cell responses.

Fresh CD4+ and CD8+ PBMC (105/well) were cultured in complete medium with either 1 or 0.2 μg of soluble peptides (N1, N2, N3, G1, G2, and E) per ml and set up in quadruplicate. Proliferation was determined in culture on day 5 by adding 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine (NEN Life Science Products, Paris, France) per well. The capacity of the PBMC to proliferate in vitro was checked in independent cultures carried out for 5 days with PHA, PPD, TT, and SEB at two concentrations (10 μg/ml and 1 μg/ml).

Depletion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was accomplished in PBMC by using anti-mouse immunoglobulin and complement. Briefly, 107 PBMC were incubated in 1 ml of SAB-free medium for 30 min at 4°C with 2 μg of anti-CD4 monoclonal antibodies (OKT4 [Orthodiagnotic Systems] and BL4 [Immunotech]) or anti-CD8 monoclonal antibodies (OKT8 [Orthodiagnotic Systems] and UCHT-4 [Sigma]). Rabbit serum complement (1 ml; Hoechst Behring, Reuil, France) was added to the cells for 45 min at 37°C. The CD4+ and CD8+ cells enrichments were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Generation of CTL lines.

PBMC were stimulated in vitro by mixing 106 PBMC (responder cells) with 106 irradiated stimulating cells (autologous PBMC were incubated overnight with 10 μg of each long peptide per ml) in complete RPMI culture medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES, nonessential amino acids, and 10% heat-inactivated SAB). Interleukin-2 (10 U/ml) was added on day 3. Responder cells were restimulated every week for 3 or 4 weeks, using autologous PBMC incubated with peptides (prepared as on day 0) in medium supplemented with 10 U of interleukin-2 per ml. The CTL were tested by using the autologous Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) cell line as targets incubated overnight with 10 μg of each long peptide (N1, N2, N3, G1, G2, and E) per 106 cells. We did not have enough cells to test all the CD8+ T cells in a 51Cr-release test (CRT) assay at the same effector-to-target-cell (E/T) ratio. However, we tested the CTL activity at an E/T ratio of 100-140 whenever it was possible. Only the CTL reactivity positive at a E/T ratio of 2 has been taken into account and, the results given at one E/T ratio are significant and representative. All the PBMC were tested after three stimulations; one more stimulation was given when the CTL activity was negative after 3 stimulations. The positive CTL activity obtained after three stimulations was confirmed after four stimulations, and the positive CTL activity obtained after four stimulations was confirmed after five stimulations. We always used as control the PBMC taken prior to immunization.

To obtain target cells presenting HIV gene products, EBV targets were infected overnight at 106 cells/ml with wild-type vaccinia virus (WT) or with HIV-1 LAI (clade B), HIV-1 MN (clade B), HIV-1 Bangui (clade A), or HIV-2 ROD Nef recombinant vaccinia virus (20 PFU/cell). The various targets (106 cells) were then washed and labelled with 100 μCi of Na251CrO4 (NEN Life Science Products). Cytolytic activity was determined in a standard 4-h 51Cr-release assay. The average spontaneous release never exceeded 20% of the total 51Cr incorporated. Results were expressed as specific Cr release, i.e., 100 × (experimental counts per minute − spontaneous counts per minute)/(maximum counts per minute − spontaneous counts per minute).

IFN-γ ELISPOT assay.

Ninety-six-well nitrocellulose plates (MultiScreen-HA; Millipore S.A., Molsheim, France) were coated overnight at 4°C with 5 μg of mouse anti-human monoclonal antibody (Genzyme Corp., Cambridge, Mass.) per ml. The wells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline and saturated with complete RPMI medium. Freshly separated or cryopreserved PBMC were added (triplicate assay; 2 × 105 cells per well) with various minimal CD8+ epitopic peptides (10 μg/ml) and incubated for 24 h at 37°C under 5% CO2. The plates were then washed and incubated for 2 h with 100 μl of polyclonal rabbit anti-human IFN-γ antibody (1/250; Genzyme). After washing, an anti-rabbit IgG-biotin conjugate (1/500; Boehringer Mannheim France S.A., Meylan, France) was incubated for 1 h. Finally, alkaline phosphatase-labelled extravidin (Sigma-Aldrich Chimie S.A.R.L, St Quentin Fallavier, France) was added for 1 h. A 100-μl volume of chromogenic alkaline phosphatase substrate (Bio Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) was added to each well to develop spots. Blue spots were counted under a microscope. Negative controls consisted of PBMC incubated in medium alone or with HLA-mismatched CD8+ epitopic peptides derived from HIV. Positive controls consisted of the activation of PBMC with 50 ng of phorbol myristate acetate per ml and 500 ng of ionomycin per ml (100 to 300 PBMC per well) or 10 μg of PHA per ml (10,000 cells per well). These strong mitogenic stimuli were used to evaluate the viability of the T lymphocytes to check the quality of the freezing. We also used positive-control HLA-matched epitopic peptides derived from EBV and influenza virus.

RESULTS

Safety of the lipopeptide vaccine.

As reported elsewhere, injections of lipopeptides were well tolerated and did not produce systemic symptoms. Injection of the lipopeptides resulted only in local erythema around the site of inoculation, which persisted for between 24 and 48 h in most patients. Further details concerning clinical data will be published elsewhere.

Induction of a humoral response to HIV-1 long peptides.

Serum samples were collected prior to vaccination (week 0) and during week 20, after the third injection. Sera were assayed for anti-Nef (N1, N2, and N3), anti-Gag (G1 and G2), and anti-Env (E) long peptide IgG antibodies by ELISA (Table 2). After three injections, anti-N1 and anti-N2 IgG antibodies were detected in vaccinated subjects. Anti-N1 antibody responses were found in 5 of the 12 volunteers, with titers varying from 2 to 7 times that of the week 0 sera. The antibody response to N2 was positive in 10 of the 12 volunteers, with titers varying from 2 to at least 20 times. Finally, no anti-N3 IgG was detected in the sera of any of the volunteers.

TABLE 2.

Detection of HIV Nef, Gag, and Env peptide-specific antibodies in the sera of immunized volunteers

| Volunteera | Time of collectionb | Recognition ofc:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 (2 × 103 to 23 × 103) | N2 (2 × 103 to 15 × 103) | N3 (2 × 103 to 23 × 103) | G1 (2 × 103 to 21 × 103) | G2 (2 × 103 to 19 × 103) | E (2 × 103 to 36 × 103) | ||

| V4.6 | W20 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 7.5 ± 0.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 8.9 ± 0.1 | 1.2 |

| V4.16 | W20 | 1.2 | 4.7 ± 0.2 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 9.7 ± 0.9 | 1.3 |

| V4.17 | W20 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 4.5 ± 0.7 | 1.2 |

| V4.18 | W20 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 1.1 |

| V4.23 | W20 | 1.0 | 8.9 ± 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 31.4 ± 1.1 | 2.8 ± 0.5 |

| V4.28 | W20 | 7.2 ± 1.1 | 9.3 ± 0.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 14.4 ± 0.1 | 5.7 ± 0.3 |

| V4.1 (QS21) | W20 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 10.4 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 0.1 |

| V4.5 (QS21) | W20 | 1.2 | 4.2 ± 0.8 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 7.5 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.3 |

| V4.19 (QS21) | W20 | 1.2 | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.8 |

| V4.21 (QS21) | W20 | 1.2 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 8.1 ± 0.2 | 1.9 |

| V4.32 (QS21) | W20 | 6.3 ± 0.6 | 13.3 ± 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 20.2 ± 2.0 | 4.0 ± 0.1 |

| V4.34 (QS21) | W20 | 5.5 ± 1.0 | 21.0 ± 2.1 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 44.6 ± 3.1 | 7.8 ± 0.5 |

Volunteers were immunized with six lipopeptides without or with adjuvant (QS21).

Sera were collected before injection of the lipopeptides (week 0) and during week 20 (W20).

The ELISA plates were coated with either Nef 66 to 97 (N1), Nef 117 to 147 (N2), Nef 182 to 205 (N3), Gag 183 to 214 (G1), Gag 253 to 284 (G2), or V3 Env 303 to 335 (E). A negative antibody titer (index = 1) was defined as the value observed in the sera of volunteers prior to immunization. The baseline obtained with the serum prior to immunization (week 0) is indicated in table as the range of fluorescence units obtained with the different sera for each long peptides tested in the ELISA. An antibody titer was defined as positive (indicated by bold type) when the serum taken after immunization (W20) gave an index of ≥2. Standard deviations are shown. The experiments were performed three times for each volunteer serum.

The sera were then assayed for anti-G1 and anti-G2 IgG antibody responses. All 12 volunteers remained negative to G1 peptides even after three injections, without or with adjuvant (QS21). In contrast, anti-G2 IgG antibodies were detected in the sera of all 12 vaccinated subjects, with titers varying from 2-fold to more than 40-fold times for six volunteers.

Finally, specific anti-E peptide antibodies were detected in the sera of two volunteers immunized without adjuvant as well as in the sera of five volunteers immunized with QS21.

The sera of 10 HIV-1-seropositive patients were also assayed by ELISA under the same experimental conditions to compare anti-Nef, anti-Gag, and anti-Env long-peptide IgG antibody responses. The results were clearly different (data not shown); there was little IgG specific to the three Nef peptides (N1, N2, and N3) in these patients. Three of them had weak responses to the G1 peptide but no antibodies specific to the G2 peptide. In contrast, the sera of 9 of the 10 seropositive patients revealed a high level of specific anti-E peptide IgG antibodies.

Humoral response to the Nef, Gag, and Env proteins.

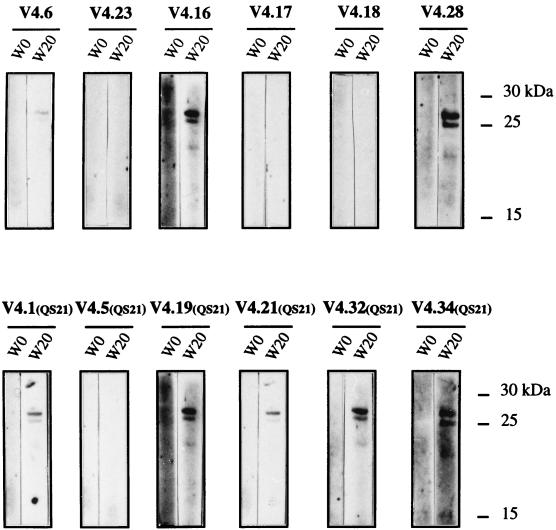

Sera from vaccinated subjects who induced specific IgG antibodies that recognized the Nef, Gag, and Env peptides contained in the vaccine were checked for their capacities to recognized the corresponding proteins. First, to determine whether N1, N2, and N3 peptide immunization induced IgG antibodies that reacted with the whole Nef protein, we assayed serum samples by Western blotting (Fig. 1). No IgG specific to the Nef protein were detected prior to immunization, whereas the Nef protein was recognized by sera collected on week 20 from eight volunteers (five immunized with and three immunized without QS21).

FIG. 1.

Immunoblot pattern of serum specific for Nef protein. Suspensions of recombinant NEF protein (10 μl) harvested from E. coli production were separated by SDS-PAGE. Sera (diluted 1/100) collected from volunteers before (W0) and after (W20) immunization were tested and revealed with a sheep horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-human immunoglobulin conjugate (1/2,000).

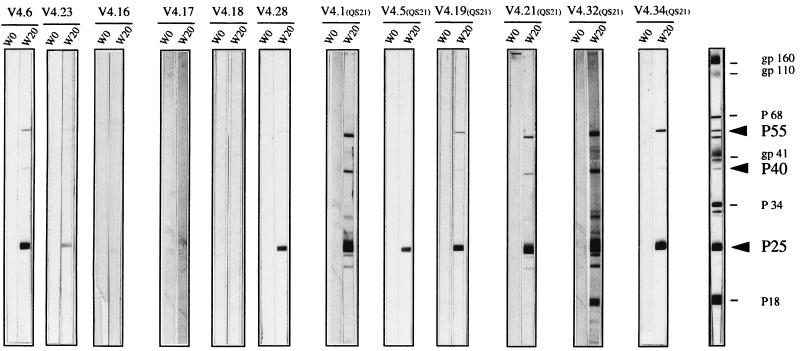

Second, there was a strong humoral response to P25 Gag protein in the sera of 9 of the 12 vaccinated subjects collected on week 20 (Fig. 2). Of these, sera from seven subjects had anti-P25 as well as anti-P40 and anti-P55 IgG antibodies (immature form of Gag protein). Moreover, it seems that sera from subjects vaccinated with lipopeptide in adjuvant induced a greater IgG antibody response to Gag protein than did sera from volunteers immunized with lipopeptides alone (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Patterns of IgG specific for Gag protein were detected by using a commercial kit (New Lav Blot I; see Materials and Methods). Sera (diluted 1/100) collected from volunteers at different time points (W0 and W20) were tested for the presence of anti-HIV-1 Gag protein IgG antibodies. We could detect the mature Gag protein (P25) and the two precursors (P40 and P55).

Because of the importance of Env protein in the induction of neutralizing or facilitating antibodies, we assayed anti-Env protein IgG antibodies. None of the sera from vaccinated subjects recognized the gp120 and gp160 proteins, and they could be readily differentiated from the sera from HIV-seropositive patients with a commercial HIV detection kit (Fig. 2). Finally, no neutralizing antibodies were detected in the sera of the 12 vaccinated subjects (data not shown).

HIV-1 peptide-specific helper T-cell response.

Proliferative responses to soluble long peptides obtained with PBMC from vaccinated subjects are shown in Table 3. The Nef, Gag, and Env long peptides caused proliferation only with the PBMC from vaccinated donors, whereas no proliferation was found prior to vaccination. The PBMC of 9 of the 10 volunteers immunized (with or without QS21) proliferated against at least one peptide after three injections (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Proliferative responses of volunteer PBMC to soluble Nef, Gag, and Env long peptides

| Volunteera | Time of collectionb | Proliferation in response toc:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 (index) | N2 (index) | N3 (index) | G1 (index) | G2 (index) | E (index) | Medium (cpm) | ||

| W0 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1 | 871 ± 25 | |

| V4.6 | W20 | 2.4 | 3.1 ± 1 | 10 ± 7 | 4.5 ± 1.1 | 7.2 ± 0.7 | 3.6 ± 0.9 | 280 ± 32 |

| W0 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 3,830 ± 232 | |

| V4.16 | W20 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 1,000 ± 168 |

| W0 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 5,708 ± 470 | |

| V4.17 | W20 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 1,228 ± 54 |

| W0 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | 1.3 | 460 ± 49 | |

| V4.18 | W20 | NDd | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| W0 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 721 ± 56 | |

| V4.23 | W20 | 3.3 ± 1.8 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 14.9 ± 3.9 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 926 ± 60 |

| W0 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 869 ± 36 | |

| V4.28 | W20 | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 1.2 | 21.0 ± 2 | 1.2 | 8.2 ± 1.6 | 7.6 ± 2.2 | 2,558 ± 186 |

| W0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 3,107 ± 521 | |

| V4.1 (QS21) | W20 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| W0 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 341 ± 20 | |

| V4.5 (QS21) | W20 | 4.6 ± 1.2 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 5.0 ± 2.2 | 776 ± 60 |

| W0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 918 ± 102 | |

| V4.19 (QS21) | W20 | 24.3 ± 3.1 | 8.5 ± 5 | 4.4 ± 1.2 | 3.1 ± 2.5 | 11.0 ± 2.7 | 9.4 ± 2.8 | 497 ± 168 |

| W0 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 3.9 ± 1 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 322 ± 21 | |

| V4.21 (QS21) | W20 | 6.5 ± 3 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 11.3 ± 4 | 3.3 ± 1.9 | 1,052 ± 82 |

| W0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 4,448 ± 75 | |

| V4.32 (QS21) | W20 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 10.1 ± 1.5 | 0.9 | 245 ± 30 |

| W0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 5,383 ± 309 | |

| V4.34 (QS21) | W20 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 1.1 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 2.2 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 7,381 ± 280 |

Volunteers immunized with lipopeptides without adjuvant.

PBMC of volunteers were collected before injection (W0) and 1 week after three injections of the six lipopeptides (W20).

105 cells were cultured with 1 μg of HIV long peptides per ml, and proliferation was measured by [3H]thymidine incorporated on day 6. The long peptides used were Nef 66 to 97 (N1), Nef 117 to 147 (N2), Nef 182 to 205 (N3), Gag 183 to 214 (G1), Gag 253 to 284 (G2), and V3 Env 303 to 335 (E). The proliferative response of PBMC from volunteers cultured in medium alone is given in the right-hand column in counts per minute. The proliferation index obtained with culture medium alone is taken as 1. Means ± standard deviations of quadruplicate cultures were expressed in counts per minute (cpm). The capacity of PBMC to proliferate in vitro was checked in independent culture with 1 μg of PHA, PPD, and SEB per ml. All PBMC proliferated in response to these antigens (data not shown). A positive index is defined as an index of ≥3 (shown in bold).

ND, not done.

Induction of proliferation in response to N1 was observed with the PBMC of 5 of the 10 volunteers, with indices varying from 3.4 to 24.3. The proliferative response to N2 was positive for only 1 of the 10 volunteers. Finally, proliferation to the N3 long peptide was observed with PBMC obtained from 4 of the 10 vaccinated volunteers, with indices varying from 3.3 to 21.

PBMC collected from the volunteers were then assayed for proliferation to G1 and G2 long peptides. Only PBMC from 2 of the 10 volunteers proliferated in response to G1 peptide after immunization. In contrast, proliferation in response to the G2 long peptide was obtained with PBMC of 9 of the 10 vaccinated subjects, with proliferative indices varying from 3.6 to at least 10 for four of them. Finally, specific proliferative responses to the E long peptide were observed in the PBMC of 6 of the 10 volunteers. It is of particular interest that PBMC of vaccinated volunteers preferentially proliferated in response to G2 (9 of 10), E (6 of 10), N1 (5 of 10), and N3 (4 of 10) long peptides. In contrast, PBMC from only 1 and 2 of the 10 volunteers proliferated in response to N2 and G1 long peptides, respectively.

Note that the depletion experiment carried out with PBMC from vaccinated subjects showed that proliferation of PBMC collected at week 20 was preferentially mediated by CD4+ T cells (data not shown).

Induction of HIV-specific CTL activity.

Tables 4 and 5 show the results of repeated and representative experiments of cytotoxicity activity tested in 12 vaccinated subjects immunized with or without QS21 adjuvant. Specific CTL activity was detected in PBMC collected from 9 of the 12 subjects after immunization. Among the PBMC from these nine vaccinated subjects, four generated CTL specific to one peptide, four generated CTL specific to two peptides, and one generated CTL specific to three peptides. All six long peptides contained in the vaccine were recognized at least by PBMC from one positive volunteer. The G2 and E lipopeptides appeared to be especially immunogenic; they were respectively recognized by PBMC from four and five volunteers.

TABLE 4.

CTL specificities in volunteers immunized with lipopeptides alone

| Lipopeptide incubated with target cellsb | % Specific lysis of effector cells at given E/T ratioa:

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V4.6

|

V4.16

|

V4.17

|

V4.18

|

V4.23

|

V4.28

|

|||||||||||||

| E/T | W0 | W20 | E/T | W0 | W20 | E/T | W0 | W20 | E/T | W0 | W20 | E/T | W0 | W20 | E/T | W0 | W20 | |

| None | 70:1 | 5 | 11 | 50:1 | 2 | 12 | 45:1 | 10 | 32 | 80:1 | 8 | 14 | 20:1 | 2 | 2 | 10:1 | 5 | 8 |

| Nef 66 to 97 | 70:1 | 9 | 17 | 50:1 | 8 | 18 | 45:1 | 13 | 21 | 80:1 | 11 | 40 | 20:1 | 2 | 2 | 10:1 | 12 | 19 |

| Nef 117 to 147 | 70:1 | 9 | 16 | 50:1 | 2 | 13 | 45:1 | 16 | 15 | 80:1 | 6 | 6 | 20:1 | 2 | 2 | 10:1 | 19 | 12 |

| Nef 182 to 205 | 70:1 | 4 | 15 | 50:1 | 2 | 24 | 45:1 | 23 | 31 | 80:1 | 6 | 6 | 20:1 | 2 | 11 | 10:1 | 2 | 4 |

| None | 70:1 | 4 | 18 | 30:1 | 5 | 5 | 20:1 | 20 | 9 | 55:1 | 8 | 6 | 24:1 | 4 | 2 | 10:1 | 2 | 2 |

| Gag 183 to 214 | 70:1 | 7 | 14 | 30:1 | 9 | 10 | 20:1 | 16 | 12 | 55:1 | NDc | ND | 24:1 | 4 | 12 | 10:1 | 2 | 2 |

| Gag 253 to 284 | 70:1 | 9 | 49 | 30:1 | 11 | 20 | 20:1 | 9 | 26 | 55:1 | 6 | 26 | 24:1 | 2 | 2 | 10:1 | 2 | 2 |

| None | 70:1 | 3 | 6 | 25:1 | 32 | 23 | 22:1 | 2 | 2 | ND | ND | 40:1 | 3 | 2 | 10:1 | 2 | 2 | |

| V3 Env 303 to 335 | 70:1 | 2 | 36 | 25:1 | 12 | 49 | 22:1 | 3 | 7 | ND | ND | 40:1 | 9 | 7 | 10:1 | 2 | 17 | |

Volunteers were immunized with lipopeptides without adjuvant. Effector cells were obtained after three (V4.6, V4.17, V4.18, V4.23, and V4.28) or four (V4.16) stimulations in vitro with each of the six long peptides. Cytotoxic activity against autologous EBV cells incubated with or without peptides was measured in a 4-h 51Cr release assay. Results are expressed as the means of duplicate tests. Cytotoxic activity was considered positive when the specific Cr release was >10% of that observed with target cells alone at two effector/target ratios. Positive results are shown in bold. The E/T ratio is the ratio of effector cells incubated with 5 × 103 labeled target cells.

Target cells were autologous PBMCs sensitized overnight with 10 μg of long peptide per ml, irradiated, and labeled with 51Cr.

ND, not done.

TABLE 5.

CTL specificities in volunteers immunized with lipopeptides and QS21 adjuvant

| Lipopeptide incubated with target cells | % Specific lysis of effector cells at given E/T ratioa

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V4.1 (QS21)

|

V4.5 (QS21)

|

V4.19 (QS21)

|

V4.21 (QS21)

|

V4.32 (QS21)

|

V4.34 (QS21)

|

|||||||||||||

| E/T | W0 | W20 | E/T | W0 | W20 | E/T | W0 | W20 | E/T | W0 | W20 | E/T | W0 | W20 | E/T | W0 | W20 | |

| None | 40:1 | 28 | 1 | 100:1 | 16 | 31 | 60:1 | 2 | 6 | 40:1 | 2 | 2 | 25:1 | 2 | 3 | 35:1 | 10 | 2 |

| Nef 66 to 97 | 40:1 | 26 | 19 | 100:1 | 10 | 23 | 60:1 | 0 | 15 | 40:1 | 2 | 2 | 25:1 | 2 | 2 | 35:1 | 2 | 2 |

| Nef 117 to 147 | 40:1 | 21 | 4 | 100:1 | 18 | 47 | 60:1 | 2 | 27 | 40:1 | 2 | 2 | 25:1 | 2 | 2 | 35:1 | 2 | 2 |

| Nef 182 to 205 | 40:1 | 23 | 10 | 100:1 | 10 | 31 | 60:1 | 0 | 0 | 40:1 | 2 | 2 | 25:1 | 2 | 2 | 35:1 | 2 | 2 |

| None | 40:1 | 28 | 2 | 140:1 | 23 | 11 | 60:1 | 0 | 0 | 46:1 | 2 | 2 | 25:1 | 2 | 2 | 35:1 | 2 | 2 |

| Gag 183 to 214 | 40:1 | 10 | 2 | 140:1 | 21 | 11 | 60:1 | 0 | 0 | 46:1 | 2 | 2 | 25:1 | 2 | 2 | 35:1 | 2 | 5 |

| Gag 253 to 284 | 40:1 | 28 | 20 | 140:1 | 20 | 68 | 60:1 | 0 | 9 | 46:1 | 2 | 2 | 25:1 | 2 | 2 | 35:1 | 5 | 23 |

| None | 70:1 | 24 | 16 | 60:1 | 22 | 14 | 60:1 | 0 | 2 | 86:1 | 7 | 13 | 25:1 | 2 | 2 | 35:1 | 5 | 3 |

| V3 Env 303 to 335 | 70:1 | 27 | 36 | 60:1 | 24 | 16 | 60:1 | 2 | 6 | 86:1 | 2 | 23 | 25:1 | 4 | 5 | 35:1 | 3 | 3 |

Volunteers immunized with lipopeptides with adjuvant. Effector cells were obtained after three [V4.5 (QS21) and V4.21 (QS21)] or four [V4.1 (QS21), V4.19 (QS21), V4.32 (QS21), and V4.34 (QS21)] stimulations in vitro with each of the six long peptides. For other details, see the footnotes to Table 4.

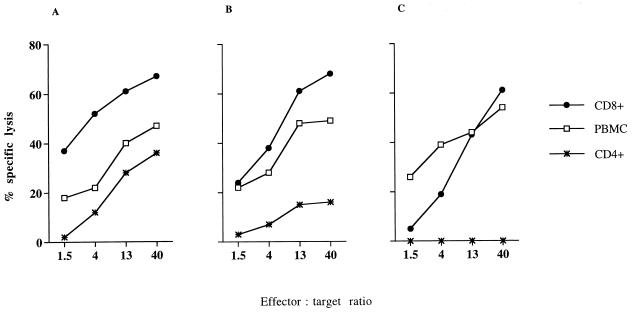

To find whether the effector cells were CD8+ T cells, as might be expected for class I-restricted antigen-specific CTL, we removed CD8+ or CD4+ T lymphocytes from the PBMC and conducted a cytotoxicity test. Depletion experiments were performed in half of the samples presenting CTL reactivity to the HIV peptides. The PBMC from the other vaccinated volunteers could not be tested because of a limited quantity of cells. Only the results obtained for vaccinated volunteer V4.1 are shown (Fig. 3). The positive anti-N1, anti-G2, and anti-E CTL obtained after four stimulations with PBMC (week 20) from volunteer V4.1 were stimulated one more time with the respective long peptides. The CD4+ and CD8+ depletions were performed after five stimulations to obtain more cells, i.e., after one more stimulation than the result shown in Table 5. PBMC and CD8+ cells from V4.1 (Fig. 3) efficiently lysed autologous EBV cells incubated with HIV-peptides. CD8+ enrichment increased the percentage of specific lysis for anti-N1 and anti-G2 at different E/T ratios. These results confirmed that anti-HIV cytotoxic activity was mediated by CD8+ T cells. However, we observed that the lytic activity of PBMC for anti-E CTL activity was substantially greater than in purified CD8+ T cells, suggesting that another population, like NK cells, could mediate part of the lytic activity observed.

FIG. 3.

The positive anti-N1, anti-G2, and anti-E CTL obtained after four stimulations with PBMC (W20) from volunteer V4.1 (results shown in Table 5) were stimulated one more time with the respective long peptides to obtain more cells. To determine the fine nature of effector cells in response to these peptides, T-cell depletion was performed with anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 antibodies and complement 1 week after the last stimulation. Target cells (EBV infected) were sensitized with the N1 (A), G2 (B), or E (C) long peptides. The HIV-1-specific CTL from volunteer V4.1 were analyzed at an E/T ratio of 1.5:1 to 40:1.

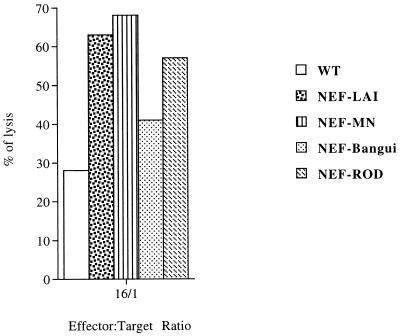

We also tested the possibility that immunization with lipopeptides was able to generate CD8+ epitopes that were expressed on infected cells by determining whether these CTL recognized and lysed virus-infected cells. Thus, PBMC from volunteer V4.5 (QS21) collected during week 20 were stimulated three times each with the Nef, Gag, and Env long peptides and tested for CTL activity against EBV cells incubated with the different long peptides (Table 5). Then the specific anti-N2 CTL were stimulated a fourth time with the N2 peptide and tested for their capacities to recognize autologous EBV targets infected with different recombinant vaccinia viruses (Fig. 4). Anti-N2 CTL obtained from volunteer V4.5 (QS21) recognized antigen naturally processed by autologous EBV lymphoblastoid cell lines LCL infected with recombinant vaccinia viruses carrying HIV nef genes from various HIV clades and strains. For the same E/T ratio, the HIV-specific CTL recognized Nef-LAI and Nef-MN (HIV-1 clade B) with the same efficiency. The percent specific lysis was lower but significant with the Nef-Bangui (HIV-1 clade A) and Nef-ROD (HIV-2) proteins. Thus, CTL generated by lipopeptide vaccination recognized, by cross-reaction, recombinant Nef proteins from different HIV strains. It should be of interest to test whether different HIV-infected cells can be recognized.

FIG. 4.

Anti-NEF CTL obtained with PBMC from volunteers V4.5 were tested for their capacities to recognize autologous EBV-infected targets infected with different recombinant Nef vaccinia viruses. For the same E/T ratio (16:1), the Nef peptide-specific CTL were tested against recombinant Nef proteins derived from HIV-1 LAI and MN (clade B), HIV-1 Bangui (clade A), and HIV-2 ROD.

HIV-specific ex vivo IFN-γ-secreted CD8+ T cells.

The gamma interferon (IFN-γ) ELISPOT assay appeared to be a very sensitive ex vivo method for quantifying and identifying activated effector CD8+ T cells, which produce lymphokines with or without lytic activity. We therefore used this method to identify epitopic CD8+ peptides recognized by the PBMC of volunteers.

Unstimulated thawed PBMC collected before and after vaccination from volunteers were tested for their ability to secrete IFN-γ in response to HLA class I-restricted viral epitopic peptides, as presented in Table 6. No response or a weak response was obtained with PBMC cultured in medium alone, whereas significant numbers of spots were detected in the presence of PHA (data not shown). Various epitopic CD8+ peptides derived from HIV-1 and contained in the lipopeptides were incubated with the corresponding HLA class I haplotype cells identified in each volunteer. PBMC from five of the six volunteers were able to secrete IFN-γ in response to at least two CD8+ peptides. Interestingly, in volunteer V4.6, two peptides, Nef 136 to 145 and Nef 190 to 198 (restricted to HLA-A2), were recognized by ELISPOT assay (Table 6), whereas no CTL activity against the three Nef long peptides was identified in this volunteer (Table 4), thus demonstrating the possibility of better characterizing a multiepitopic CD8+-T-cell response by an ELISPOT assay. On the other hand, we were also able to correlate cytotoxic activity against Nef 66 to 97 detected in volunteer V4.18 (Table 4) with two CD8+ epitopes included in this long peptide by an ELISPOT assay (Nef 73 to 82 and Nef 84 to 92). Further investigation is in progress to complete this multiepitopic CD8+-T-cell analysis.

Similarly, by studying non-HIV viral peptides derived from EBV (EBN 416 to 424; HLA-A11 restricted) and influenza virus (M 58 to 66; HLA-A2-restricted), we observed that PBMC collected from volunteers before and after vaccination could recognize those peptides with the appropriate HLA restriction. This indicates that the quality of effector CD8+ function is similar in the two PBMC samples taken from the same volunteer.

DISCUSSION

The peptide-based approach presents several advantages over that of conventional vaccines (proteins, whole DNA gene, and live recombinant vectors). The immune response can be directed against highly conserved epitopes that might be crucial for pathogens such as HIV. This approach also provides the ability to elicit CTL responses directed against subdominant epitopes or to eliminate epitopes that could induce deleterious immune responses. The immunogenicity of synthetic peptides is enhanced by adding a lipid tail at one end of the sequence. Thus, several studies with mice (22, 29), macaques (24), and humans (20, 33) have shown that lipopeptides are highly immunogenic, inducing strong B- and T-cell responses in vivo.

We therefore analyzed B- and T-cell responses induced by vaccination with HIV lipopeptides in seronegative volunteers who were given three injections of either 100, 250, or 500 μg of each lipopeptide with or without an adjuvant (QS21).

Vaccinated subjects induced specific IgG antibodies that recognized the Nef, Gag, and Env peptides in the vaccine, as well as the corresponding proteins. The capacity of the vaccine to induce IgG specific to Nef protein could be significant, since the HIV-1 Nef antigen can be present on the surface of infected cells, allowing the formation of a syncytium between an infected and an uninfected cell. This function can be blocked by anti-Nef immunoglobulin antibodies (10, 25). The G2 peptide corresponding to residues 253 to 284 of the P25 Gag protein was extremely immunogenic and was recognized by all vaccinated subjects. The Gag protein profile (P25, P40, and P55) showed that immunization induced recognition of both the immature and mature Gag proteins. Finally, we obtained a specific response to the V3 gp120 consensus peptide in some vaccinated subjects, but none of them recognized the gp120 Env protein. Moreover, no neutralizing antibodies were detected in the sera of the 12 subjects after three injections. Perhaps we needed to administer additional boosts to raise these neutralizing antibodies, as described in experimental models (31). Results also showed that antibody responses to the six long peptides in sera obtained from vaccinated volunteers and from seropositive patients were different. This point is of particular importance, since one of the rationales for using peptide immunization is to target the immune response to domains of proteins that are not recognized by antibodies raised after immunization or infection with full-length viral protein. Such regions of proteins might be critical in protective immunity, since they could be more well conserved or the target of functional antibodies.

CD4+ T cells are necessary for the induction and maintenance of the effector functions of CD8+ T cells. In addition, CD4+ T cells activate professional antigen-presenting cells, which are thereby rendered highly effective in stimulating CD8+ T cells (19, 26). We and others have previously shown that TH1 activity is required for the induction of specific CD8+ T lymphocytes by lipopeptide vaccination (23, 30, 33). A recent study in which humans were immunized with a lipopeptide hepatitis B virus vaccine showed that the helper T-cell response is important for the development of CTL responses (20). This lipopeptide contained a promiscuous human T-helper epitope derived from tetanus toxoid (TT 830 to 843) and a CTL epitope specific to the hepatitis B virus (HBV 18 to 27) linked as a single colinear synthesis unit. A significant helper T-cell response was associated with a sustained CTL response. We also found that T-helper activity was required for the induction of specific CD8+ T lymphocytes. The HIV-specific proliferative CD4+-T-cell response of PBMC from several vaccinated subjects was associated with the induction of HIV-specific CTL activity. In contrast, PBMC from a volunteer that did not proliferate in response to peptide did not contain specific CTL. Our results also indicated that CD4+ and CD8+ epitopes in the lipopeptide vaccine were not necessarily located in the same long peptide. It has been shown that poor CD4+-T-cell responses during HIV infection are correlated with high viral loads (28). Thus, the strong and multiepitopic HIV-1 CD4+-T-cell response obtained in our clinical trial might also have important implications for immunotherapy and for understanding the role of HIV-specific CD4+ in the control of infection.

A recent report showed that CTL are essential for controlling HIV infection (32). HIV type 1-specific CD8+ T cells are associated with the initial reduction in early viremia during primary infection, as well as with maintenance of the asymptomatic phase of infection (17). On the other hand, noncytotoxic CD8+ T cells may also be critical for preventing progression to disease following HIV infection (8, 21). In the present study, HIV-specific CTL were obtained after three injections. Among the sera from the nine positive subjects, four generated specific CTL to one long peptide and five reacted against two or three long peptides. To better identify multiepitopic CD8+-T-cell responses, we have begun to test CTL activity against the corresponding optimal short peptides spanning the sequence of the long peptides. Moreover, we also showed that HIV-specific CTL induced by vaccination can recognize naturally processed viral protein. Thus, CTL induced by vaccination recognized various HIV viruses by cross-reaction.

We also used an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay, which is a very sensitive ex vivo method, to better characterize and quantify anti-HIV-1 CD8+-T-cell responses induced in vaccinated subjects. We were thus able to identify the epitopic short peptides recognized by activated effector CD8+ T cells that produced lymphokines with or without lytic activity. IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells specific for HIV-1 peptides were detected ex vivo in five of the six subjects tested at week 20, indicating that effector CD8+ are present at a detectable frequency. The number of IFN-γ CD8+ T cells obtained with short HIV epitopes is comparable to that obtained with M 58 to 66 peptides derived from influenza virus-seropositive subjects (18). In contrast, the number of HIV-specific ex vivo IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells obtained from HIV-seropositive patients could be 5 to 10 times greater (7). We postulate that the presence of the virus in HIV-seropositive patients induces permanent stimulation of specific HIV–IFN-γ CD8+ T cells.

In a previous study, lipopeptide vaccine was found to induce a CTL response in a preclinical SIV-infected macaque model, but this CTL response was essentially monoepitopic, leading to selection and to the emergence of virus escape mutants (24). This is in agreement with the observation of Koening et al., who found that the transfer of an HIV-1-specific CTL clone to AIDS patients led to the emergence of HIV variants and subsequent disease progression (16). The limitation of this approach is that a monospecific CTL response would lead to vaccine failure. Thus, the polyepitopic response we obtained with the Nef, Gag, and Env proteins is of particular interest, because our vaccine elicits a polyclonal CTL response.

Table 7 summarizes the immune responses obtained in the vaccinated subjects. The various doses of the lipopeptides were well tolerated by the vaccinated subjects. The lowest dose of lipopeptide (100 μg) induced an immune response in volunteer V4.5 (QS21). After vaccination, CTL induction was associated with T-helper activity. There was also induction of helper activity without CTL induction in some vaccinated subjects (V4.23 and V4.32). The antibody responses to the long peptides (contained in the vaccine) were also associated with the CD4+-T-cell responses, except in one subject (V4.17). The recognition of the Nef and Gag proteins was correlated with the presence of antibodies specific to the long peptides. Humoral and cellular immune responses were induced in volunteers immunized with or without QS21 adjuvant. The only adjuvant effect obtained was in the intensity of the response to the HIV-1 proteins. There was a multispecific immune response (antibodies and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells) in most of the vaccinated subjects. The G2 long peptide appeared to be the most immunogenic peptide with respect to both humoral and cellular reactivities elicited. Therefore, we believe that development of an anti-HIV lipopeptide vaccine is a suitable method to induce B- and T-cell multiepitopic responses in humans.

TABLE 7.

Summary table comparing antibody, proliferative, and CTL induction for each individual lipopeptide in volunteers immunized at week 20 with or without adjuvant

| Volunteers | Peptide-specific antibody (ELISA)

|

Protein detected by western blot

|

Proliferative response

|

CTL activity

|

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | N2 | N3 | G1 | G2 | E | NEF | GAG | N1 | N2 | N3 | G1 | G2 | E | N1 | N2 | N3 | G1 | G2 | E | |

| V4.6 | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| V4.16 | − | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| V4.17 | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| V4.18 | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | NDa | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | − | − | − | + | ND |

| V4.23 | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| V4.28 | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| V4.1 (QS21) | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| V4.5 (QS21) | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | − |

| V4.19 (QS21) | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | − |

| V4.21 (QS21) | − | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| V4.32 (QS21) | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| V4.34 (QS21) | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − |

ND, not done.

In conclusion, it has recently been shown in experiments with macaques that a strong TH1 response is required for induction of a multiepitopic CTL response after lipopeptide vaccination (23). To improve CD8+-T-cell responses obtained by lipopeptide vaccination, a new formulation will be tested, in which long HIV-1 peptides will be mixed with a lipopeptide containing a promiscuous human T-helper epitope derived from tetanus toxoid. Lipopeptides can also be used as a prime boost after immunization, using recombinant poxvirus containing a complex combination of HIV genes. This strategy could avoid the induction of an immune response to the vector.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are very grateful to Marylène Garcette, Jessintha Gaston, and Céline Igéa for excellent technical assistance. We also thank the volunteers for their cooperation and the ANRS for continuous support and assistance in the recruitment and selection of volunteers. We acknowledge Marie-Pierre Treilhou, Sandra Fournier, Naïma Kerbouche, and Vincent Feuillie of the Pasteur Hospital vaccine trial center. The English text was edited by Noah Hardy.

This study was supported by grants from the Institut National de la Santé et la Recherche Médical (INSERM), ANRS. H. Gahéry-Ségard is supported by a fellowship from ANRS.

REFERENCES

- 1.BenMohamed L, Gras-Masse H, Tartar A, Daubersies P, Brahimi K, Bossus M, Thomas A, Druilhe P. Lipopeptide immunization without adjuvant induces potent and long-lasting B, T helper, and cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses against a malaria liver stage antigen in mice and chimpanzees. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1242–1253. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clements-Mann M L, Weinhold K, Matthews T J, Graham B S, Gorse G J, Keefer M C, McElrath M J, Hsieh R H, Mestecky J, Zolla-Pazner S, Mascola J, Schwartz D, Siliciano R, Corey L, Wright P F, Belshe R, Dolin R, Jackson S, Xu S, Fast P, Walker M C, Stablein D, Excler J L, Tartaglia J, Paoletti E A. v. e. Group. Immune responses to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 induced by canarypox expressing HIV-1 MN gp120, HIV-1 SF2 recombinant gp120, or both vaccines in seronegative adults. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1230–1246. doi: 10.1086/515288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connan F, Hlavac F, Hoebeke J, Guillet J G, Choppin J. A simple assay for detection of peptides promoting the assembly of HLA class I molecules. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:777–780. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connor R, Korber B, Graham B, Hahn B, Ho D D, Walker B, Neumann A, Vermund S, Mestecky J, Jackson S, Fenamore E, Cao Y, Gao F, Kalams S, Kunstman K, McDonald D, McWilliams N, Trkola A, Moore J, Woonsky S. Immunological and virological analyses of persons infected by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 while participating in trials of recombinant gp120 subunit vaccines. J Virol. 1998;72:1552–1576. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1552-1576.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Couillin I, Culmann-Penciolelli B, Gomard E, Choppin J, Levy J P, Guillet J G, Saragosti S. Impaired CTL recognition due to genetic variations in the main immunogenic region of the HIV-1 Nef protein. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1129–1134. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalod M, Dupuis M, Deschemin J C, Goujard C, Deveau C, Meyer L, Ngo N, Rouzioux C, Guillet J G, Delfraissy J F, Sinet M, Venet A. Weak anti-HIV CD8+ T-cell effector activity in HIV primary infection. J Clin Investig. 1999;104:1431–1439. doi: 10.1172/JCI7162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalod M, Dupuis M, Deschemin J C, Sicard D, Salmon D, Delfraissy J F, Venet A, Sinet M, Guillet J G. Broad intense anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) ex vivo CD8+ responses in HIV type 1-infected patients: comparison with anti-Epstein-Barr virus responses and changes during antiretroviral therapy. J Virol. 1999;73:7108–7116. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7108-7116.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferbas J. Perspectives on the role of CD8+ cell suppressor factors and cytotoxic T lymphocytes during HIV infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1998;14:153–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrari G, Humphrey W, McElrath M, Excler J, Duliege A M, Clements M L, Corey L C, Bolognesi D P, Weinhold K J. Clade B-based HIV-1 vaccines elicit cross-clade cytotoxic T lymphocyte reactivities in uninfected volunteers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1396–1401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujinaga K, Zhong Q, Nakaya T, Kameoka M, Meguro T, Yamada K, Ikuta K. Extracellular NEF protein regulates productive HIV-1 infection from latency. J Immunol. 1995;155:5289–5298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gahéry-Ségard H, Farace F, Godfrin D, Gaston J, Lengagne R, Boulanger P, Guillet J-G. Immune response to recombinant capsid proteins of adenovirus in humans: anti-fiber and anti-penton base antibodies have a synergistic effect in neutralizing activity. J Virol. 1998;72:2388–2397. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2388-2397.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gauduin M C, Glickman R L, Means R, Johnson R P. Inhibition of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) replication by CD8+ T lymphocytes from macaques immunized with live attenuated SIV. J Virol. 1998;72:6315–6324. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6315-6324.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham B, Wright P. Candidate AIDS vaccines. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1331–1339. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511163332007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson R P, Lifson J D, Czajak S C, Stefano Cole K, Manson K H, Glickman R, Yang J, Montefiori D C, Montelaro R, Wyand M S, Desrosiers R C. Highly attenuated vaccine strains of simian immunodeficiency virus protect against vaginal challenge: inverse relationship of degree of protection with level of attenuation. J Virol. 1999;73:4952–4961. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4952-4961.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klinguer C, David D, Kouach M, Wieruszeski J M, Tartar A, Marzin D, Levy J P, Gras-Masse H. Characterization of a multi-lipopeptides mixture used as an HIV-1 vaccine candidate. Vaccine. 1999;18:259–267. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00196-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koening S, Conley A J, Brewah Y A, Jones G M, Leath S, Boots L J, Davey V, Pantaleo G, Demarest J F, Carter C. Transfer of HIV-1 specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes to an AIDS patient leads to selection for mutant HIV variants and subsequent disease progression. Nat Med. 1995;1:330–336. doi: 10.1038/nm0495-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koup R A, Salfrit J T, Cao Y, Andrews C A, McLeod G, Borkowsky W, Farthing C, Ho D D. Temporal association of cellular immune responses with the initial control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 syndrome. J Virol. 1994;68:4650–4655. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4650-4655.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lalvani B A, Brookes R, Hambleton S, Britton W J, Hill A V S, McMichael A J. Rapid effector in CD8+ memory T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:859–865. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.6.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lanzavecchia A. Immunology. Licence to kill. Nature. 1998;393:413–414. doi: 10.1038/30845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livingston B D, Crimi C, Grey H, Ishioka G, Chisari F V, Fikes J, Grey H, Chesnut R W, Sette A. The hepatitis B virus-specific CTL responses induced in humans by lipopeptide vaccination are comparable to those elicited by acute viral infection. J Immunol. 1997;159:1383–1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackewicz C, Barker E, Greco G, Reyes-Teran G, Levy J. Do beta-chemokines have clinical relevance in HIV infection? J Clin Investig. 1997;100:921–930. doi: 10.1172/JCI119608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinon F, Gras-Masse H, Boutillon C, Tartar A, Levy J P. Immunization of mice with lipopeptides bypasses the prerequisite for adjuvant: immune response of BALB/c mice to human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein. J Immunol. 1992;149:3416–3422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mortara L, Gras-Masse H, Rommens C, Venet A, Guillet J G, Bourgault-Villada I. Type 1 CD4+ T-cell help is required for induction of antipeptide multispecific cytotoxic T lymphocytes by a lipopeptidic vaccine in rhesus macaques. J Virol. 1999;73:4447–4451. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.4447-4451.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mortara L, Letourneur F, Gras-Masse H, Venet A, Guillet J G, Bourgault-Villada I. Selection of virus variants and emergence of virus escape mutants after immunization with epitope vaccine. J Virol. 1998;72:1403–1410. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1403-1410.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otake K, Fujii Y, Nakaya Y, Nishino T, Zhong Q, Fujinaga K, Kameola M, Ohki K, Ikuta K. The carboxyl-terminal region of HIV-1 Nef protein is a cell surface domain that can interact with CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1994;153:5826–5837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ridge J P, Di Rosa F, Matzinger P. A conditioned dendritic cell can be a temporal bridge between a CD4+ T-helper and a T-killer cell. Nature. 1998;393:474–478. doi: 10.1038/30989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romieu R, Baratin M, Kayobanda M, Guillet J-G, Viguier M. IFN-γ secreting Th cells regulate both the frequency and avidity of epitope-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes induced by peptide immunization: an ex-vivo analysis. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1273–1279. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.9.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenberg E, Billingsley J, Caliendo A, Boswell S, Sax P, Kalans S, Walker B. Vigorous HIV-1 specific CD4+ T cell responses associated with control of viremia. Science. 1997;278:1447–1450. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5342.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sauzet J P, Deprez B, Martinon F, Guillet J G, Gras-Masse H, Gomard E. Long-lasting anti-viral cytotoxic T lymphocytes induced in vivo with chimeric-multirestricted lipopeptides. Vaccine. 1995;13:1339–1345. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sauzet J P, Gras-Masse H, Guillet J G, Gomard E. Influence of strong CD4 epitope on long-term virus-specific cytotoxic T cell responses induced in vivo with peptides. Int Immunol. 1996;8:457–465. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sauzet J P, Moog C, Krivine A, Martinon F, Bossus M, Gras-Masse H, Tartar A, Guillet J G, Gomard E. Adjuvant is required when using Env lipopeptide construct to induce HIV type 1-specific neutralizing antibody responses in mice in vivo. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1998;14:901–909. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmitz J E, Kuroda M J, Santra S, Sasseville V G, Simon M A, Lifton M A, Racz K T, Dalesandro M, Scallon B J, Ghrayed J, Forman M A, Montefiori D C, Rieber E P, Letvin N L, Reimann K A. Control of viremia in simian immunodeficiency virus infection by CD8+ lymphocytes. Science. 1999;283:857–860. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vitiello A, Ishioka G, Grey H M, Rose R, Farness P, LaFond R, Yuan L, Chisari F V, Furze J, Bartholomeuz R, Chesnut R. Development of a lipopeptide-based therapeutic vaccine to treat chronic HBV infection. I. Induction of a primary cytotoxic T lymphocyte response in humans. J Clin Investig. 1995;95:341–349. doi: 10.1172/JCI117662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]