The randomised controlled trial has become the gold standard for evidence based medicine; through the unbiased comparison of competing treatments it is possible to accurately quantify the cost-benefits and harm of individual treatments. This allows clinicians to offer patients an informed choice and provides the data on which purchasing authorities can make financial decisions. We, of course, subscribe to this view but also recognise this as a gross oversimplification of the power of the randomised controlled trial. The randomised controlled trial is the expression of deductive science in clinical medicine. Not only is it the most powerful tool we have for subjecting therapeutic hypotheses to the hazard of refutation1 but also the biological fallout from such trials should allow clinical scientists to refine biological hypotheses. Trials of treatments for breast cancer have, at least twice, contributed substantially to a paradigm shift in our understanding of the disease.2

Summary points

Clinical trials allow clinicians to accurately inform patients with breast cancer of the benefits and harm of different treatments

Breast conserving techniques produce equivalent survival outcomes as more radical operations, but without the anticipated improvement in psychosocial morbidity

The introduction of adjuvant systemic treatments has been associated with a significant fall in mortality from breast cancer in all age groups antedating the start of the national breast screening programme

Counterintuitive results from clinical trials are being incorporated into an emerging conceptual model of the disease

Trials of local therapy

Postoperative radiotherapy

The first randomised trial in the management of early breast cancer can be credited to the Christie Hospital in Manchester. Patients undergoing radical mastectomy were randomised to receive postoperative radiotherapy or not.3 The study found no difference in survival, although the morbidity of the combined procedure was substantial, with 30% of patients who received radiotherapy suffering lymphoedema. It took nearly two decades for the biological importance of those observations to be appreciated and for two trials to seriously challenge the prevailing belief of the centrifugal, mechanistic spread of breast cancer.4,5 The more radical treatments in these trials (surgery plus radiotherapy) were associated with a reduced rate of local relapse, but failure to treat the axillary nodes either by surgery or radiotherapy left the long term survival unchanged.

More mature follow up of the early radiotherapy trials, together with later meta-analysis, provided another curious and unexpected result that might be considered part of the biological fallout of the deductive process. An excess mortality from cardiovascular events, particularly in those patients with left sided breast cancer, compensated for a modest reduction in mortality from breast cancer.6 Two recent studies of postoperative radiotherapy for patients with poor prognosis support these observations, which challenge the contemporary belief of biological predeterminism7,8 (more of this later).

Surgery

The first randomised controlled trial of breast conserving surgery compared with classical radical mastectomy was conducted by Sir Hedley Atkins and colleagues at Guy’s Hospital.9 This trial has been criticised for the inadequate dose of postoperative radiotherapy, but the long term results demonstrated an equivalence in outcome for node negative disease but poorer survival in the group with node positive disease treated by breast conserving surgery. Subsequently, larger and perhaps better conducted trials addressed the same issue; all have demonstrated an equivalence in survival between the conservative and more radically treated groups.10 Inevitably, the penalty of breast conservation was a modest but significantly higher rate of local relapse, and perhaps these events, or their anticipation, prevented the expected improvement in psychological morbidity with breast conserving surgery11

Conclusions

Forty years of controlled trials in the local treatment of breast cancer have provided us with some reasonably robust conclusions: the more radical the treatments the better the local control, but also the greater physical morbidity. Breast conserving techniques—which usually involve wide local excision, axillary node dissection, and radiotherapy—do not increase the risk of distant relapse and death but have had no demonstrable effect on psychosocial or psychosexual morbidity.12 The untreated axilla might be regarded as an index of systemic disease. Even though up to 30% of axillas contain occult metastases, failure to treat them is associated with a remarkably low incidence of progression and uncontrolled regional recurrence.13,14 Finally, there is the tantalising suggestion that, if the excess deaths from cardiovascular events could be excluded, postoperative radiotherapy for patients with poor prognosis might be associated with a 5% reduction in late distant relapse and death.6,15 These observations all have to be incorporated in the evolving paradigm and further evaluated by clinical trials.

Trials of adjuvant systemic therapy

Endocrine manipulation

Ovarian ablation

It is just over 100 years since George Beatson described the dramatic responses of three women with advanced breast cancer to surgical castration.16 This approach became standard treatment for premenopausal women with advanced breast cancer, and provided the first approach to trials of adjuvant systemic therapy by pioneers Dr Cole (Manchester)17 and Dr Nissen-Meyer (Oslo).18 These early trials of ovarian ablation produced provocative hints that the natural course of breast cancer could be perturbed by a systemic approach. Unfortunately, they were underpowered statistically, and, although they suggested that relapse free survival could be prolonged, it was not until the publication of the first world overview (see below) that we could confidently conclude that such an approach improved absolute survival.19

Endocrine ablation has fallen out of fashion, but we predict a renewed interest after the presentation of early results from modern trials using luteinising hormone releasing hormone agonists as a reversible method of ovarian suppression.20 However, a concern about this approach must be the possible increased incidence of osteoporosis and heart disease among women with an early artificial menopause.

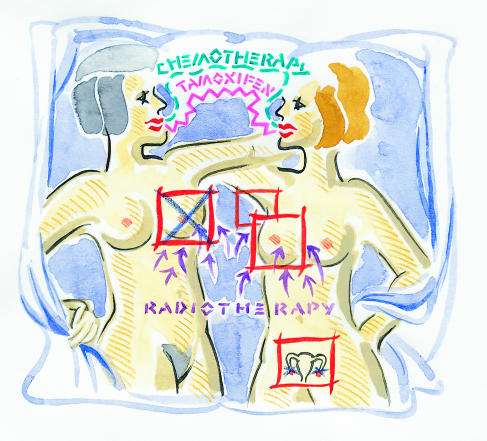

SUE SHARPLES

Tamoxifen

The next endocrine approach was the use of tamoxifen, developed as an “oral antioestrogen” in the late 1960s.21 Its clinical efficacy in advanced breast cancer was demonstrated in the early 1970s, and it was introduced into trials of adjuvant systemic therapy in the late ’70s. A survival advantage from two years of treatment with tamoxifen was reported in 1983,22 and many other trials reported similar results. The first world overview of data available in 1985 demonstrated unequivocally that, for unselected patients, tamoxifen was associated with a highly significant improvement in relapse free and overall survival.19 Since then trials have addressed the issue of combinations of chemotherapy and endocrine therapy23 and have looked at the optimum duration of tamoxifen treatment.24,25

Fascinating biological fallout has emerged. Perhaps most notable was the first report in 1985 that two years of tamoxifen treatment significantly reduced the incidence of contralateral breast cancers,26 which in part contributed to the development of trials for prevention of breast cancer among women deemed to be at high risk. Furthermore, the simplistic assumption that tamoxifen was of benefit only in women who had oestrogen receptor positive tumours has been refuted. There are now convincing data that tamoxifen given in the absence of chemotherapy to postmenopausal women has substantial benefits for patients whose tumours are oestrogen receptor negative.27 A biological rationale for these observations has evolved with the realisation that tamoxifen has alternative mechanisms of action independent of its binding capacity for oestrogen receptor. This may involve the induction of transforming growth factor β from stromal fibroblasts, the down regulation of insulin-like growth factor, and perhaps a previously unrecognised effect on angiogenesis.

Adjuvant chemotherapy

Short term chemotherapy

One of the first trials of adjuvant chemotherapy was carried out by Roar Nissen-Meyer (one of the great unsung heroes of the subject), who studied the effect of five days’ perioperative treatment with cyclophosphamide.28 This approach was based on the belief, current at that time, that prognosis might be in part determined by cancer cells shed at the time of surgery. His initial results were encouraging, suggesting an absolute improvement in 10 year survival of about 10%. Unfortunately, the survival benefit could not be corroborated by a large scale trial mounted by the Cancer Research Campaign Breast Cancer Trials Group.29 Other trials, typically employing six cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy, have effectively refuted the suggestion that a short course of perioperative chemotherapy might be of value.23

Long term chemotherapy

The seminal studies that demonstrated that long term chemotherapy could have an important survival advantage emerged from the national surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project, led by Professor Bernard Fisher,30 and the historic trial of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil led by Dr Gianni Bonadonna in Milan.31 It was probably this second trial more than any other that established the role of adjuvant chemotherapy in the management of early breast cancer. Many subsequent trials have attempted to fine tune or better select the optimum duration and combination of cytotoxic drugs.

It became clear from the early results that premenopausal women gain the greatest benefit from chemotherapy, and to some extent the benefit could be predicted by the onset of amenorrhoea. This observation led to a continuing debate as to whether a component of the action of adjuvant chemotherapy might be related to chemical ovarian ablation.32 However, with longer follow up and meta-analysis of trials, there is unequivocal evidence that adjuvant chemotherapy is also of modest value in postmenopausal women.33 Research continues in this area, including studies addressing possible synergistic or additive effects of endocrine therapy and chemotherapy.

Several studies have also investigated the use of primary (neoadjuvant) chemotherapy.34–36 These have shown that, in spite of treatment causing dramatic down staging of the original tumour, overall survival is unchanged.

High dose chemotherapy

Frustrated by the limitations of conventional chemotherapy, many medical oncologists, led by groups in the United States, embarked on programmes of high dose chemotherapy with bone marrow transplant or stem cell rescue. Even before the results of randomised controlled trials became available, such treatments were demanded (off trial) by medical oncologists and their patients, leading to some high profile court cases in the United States. However, at the meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in Atlanta (May 1999) it was reported that three trials of high dose chemotherapy had found no advantage. In our view high dose chemotherapy is the reductio ad absurdum of a conceptual belief no longer tenable. It echoes the frustrations of doctors in the 1960s, when extended radical mastectomies became fashionable among the surgical zealots.

Contribution of the world overview

By 1985 there were some tens of thousands of women already randomised into trials comparing different local regional regimens or comparing adjuvant systemic therapy with an untreated control group. It had become too complicated for any individual to make sense from even the most systematic of reviews of the literature. Furthermore, as many of these trials were seriously underpowered to detect small but clinically important differences, the scene was set for the first world overview.19

This was undertaken with the support of the United Kingdom Coordinating Committee of Cancer Research and masterminded by Professor Richard Peto’s group at Oxford University. This overview demonstrated with enormous statistical confidence the advantages of adjuvant chemotherapy for premenopausal women, tamoxifen for postmenopausal women, and the surprise finding that ovarian ablation could produce benefits of the same order as that achieved by 12 cycles of treatment with cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil. Over the next 10 years, tens of thousands of women were entered into further randomised trials that allowed us to extend and refine the observations of the first world overview. Subsequent analyses were carried out in 1990 and 1995 and published two to three years later (see box).23,27,33

Key results from the overview of breast cancer trials

Prophylactic radiotherapy after mastectomy is associated with a significant reduction in local relapse but no major net effect on survival. Mortality from breast cancer is slightly reduced, but this is to some extent counterbalanced by a small excess in cardiac mortality

Breast conserving regimens produce equivalent survival outcomes to more radical approaches

Ovarian ablation, either by surgical castration or radiation induced menopause, is associated with roughly 25% relative risk reduction in mortality from breast cancer at 15 years

Adjuvant chemotherapy using multidrug regimens for six cycles or more is associated with roughly 30% relative risk reduction in mortality from breast cancer in premenopausal women and about half this in postmenopausal women

Adjuvant tamoxifen given for two years or more is of benefit in all subgroups of patients except premenopausal women with oestrogen receptor negative tumours. Indirect comparisons suggest that five years’ treatment might be better than two years’ and that it is associated with almost 50% reduction in the risk of contralateral breast cancer

Since the publication of the first world overview there has been a significant reduction in mortality from breast cancer among all age groups, both in the United States and the United Kingdom, which closely parallels that which might be expected by the widespread adoption of systemic treatment.37

The future

Over the past few years the rate of progress has slowed, and, apart from fine tuning the duration of tamoxifen treatment and the optimum selection of cytotoxic drugs, the important new results are negative ones. Primary chemotherapy has so far failed to demonstrate survival advantages, and the recent announcement of negative results for at least three of the trials of high dose chemotherapy with stem cell rescue perhaps mark the boundary of the contemporary paradigm.

The next leap forward will require better understanding of the molecular basis of breast cancer, but, in planning future strategies, it will also be necessary to learn from the lessons of the past and to incorporate the clinical inconsistencies within the contemporary model. We have reached an exciting time in the treatment of early breast cancer, when we can build on the successes of the past, attempt to understand the failures, and incorporate the clinical observations and our new biological understanding into a revolutionary model of disease that will direct therapeutic innovations for the new millennium.

Footnotes

Competing interests: MB and JH have been reimbursed by AstraZeneca, manufacturer of Nolvadex and Zoladex, for attending several conferences and receive research funding from the same company, which contributes towards the costs of running three trials of these drugs. MB has also received fees for speaking at meetings organised by Zeneca concerning endocrine treatment of breast cancer.

References

- 1.Holmberg L, Baum M. Work on your theories! Nature Med. 1996;2:844–846. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuhn T. The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: Chicago University Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paterson R, Russell MH. Clinical trials in malignant disease. Part III. Breast cancer: evaluation of postoperative radiotherapy. J Faculty Radiol. 1959;10:175–180. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher B, Montague E, Redmond C. Findings from NSABP protocol No B-04—comparison of radical mastectomy with alternative treatments for primary breast cancer. I: Radiation compliance and its relation to treatment outcome. Cancer. 1980;46:1–13. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800701)46:1<1::aid-cncr2820460102>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Research Campaign Working Party. Cancer Research Campaign (King’s/Cambridge) trial for early breast cancer. Lancet. 1980;ii:55–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuzick H, Stewart H, Rutqvist L, Houghton J, Edwards R, Redmond C, et al. Cause-specific mortality in long-term survivors of breast cancer who participated in trials of radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:447–453. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Overgaard M, Christensen JJ, Johansen H. Postmastectomy irradiation in high-risk breast cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 1988;27:707–714. doi: 10.3109/02841868809091773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ragaz J, Jackson SM, Le N, Plenderleith IH, Spinelli JJ, Basco VE, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy in node-positive premenopausal women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:956–962. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710023371402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atkins H, Hayward JL, Klugman DJ, Wayte AB. Treatment of early breast cancer: a report after ten years of a clinical trial. BMJ. 1972;ii:423–429. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5811.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Effects of radiotherapy and surgery in early breast cancer: an overview of randomised trials. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1444–1455. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511303332202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fallowfield LJ, Baum M, Maguire GP. Effects of breast conservation on psychological morbidity associated with diagnosis and treatment of early breast cancer. BMJ. 1986;293:1331–1334. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6558.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fallowfield LJ, Baum M. Psychosocial problems associated with the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. In: Bland KI, Copeland EM III, editors. The breast. Philadelphia: WB Saunders & Co; 1991. pp. 1081–1092. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher B, Montague E, Redmond C. Comparison of radical mastectomy with alternative treatments for primary breast cancer. Cancer. 1977;39:2827–2839. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197706)39:6<2827::aid-cncr2820390671>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houghton J, Baum M, Haybittle JL.on behalf of the Closed Trials Working Party of the CRC Breast Cancer Trials Group. Role of radiotherapy following total mastectomy in patients with early breast cancer World J Surg 199418117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haybittle JL, Brinkley D, Houghton J, A’Hern RP, Baum M. Postoperative radiotherapy and late mortality: evidence from the Cancer Research Campaign trial for early breast cancer. BMJ. 1989;298:1611–1614. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6688.1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beatson G. On the treatment of inoperable cases of carcinoma of the mamma: suggestions for a new method of treatment with illustrative cases. Lancet. 1896;ii:104–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cole MP. A clinical trial of an artificial menopause in carcinoma of the breast. Inserm. 1975;55:143–150. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nissen-Meyer R. The role of prophylactic castration in the therapy of human mammary cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1967;3:395–403. doi: 10.1016/0014-2964(67)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. A systematic overview of all available randomized trials of adjuvant endocrine and cytotoxic therapy. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1990. pp. 1–207. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rutqvist LE. Zoladex and tamoxifen as adjuvant therapy in premenopausal breast cancer: a randomised trial by the Cancer Research Campaign (CRC) Breast Cancer Trials Group, the Stockholm Breast Cancer Study Group, the South-east Sweden Breast Cancer Group & Gruppo Interdisciplinare Valutazione Interventi in Oncologia (GIVIO) [abstract] Proc ASCO. 1999;18:67a. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harper PK, Walpole A. Contrasting endocrine activities of the cis and trans isomers in a series of triphenyl ethylenes. Nature. 1966;212:87. doi: 10.1038/212087a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baum M, Brinkley DM, Dossett JA, McPherson K, Patterson JS, Rubens RD, et al. Improved survival amongst patients treated with adjuvant tamoxifen after mastectomy for early breast cancer. Lancet. 1983;i:450. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90406-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Systemic treatment of early breast cancer by hormonal, cytotoxic, or immune therapy. 133 randomised trials involving 31 000 recurrences and 24 000 deaths among 75 000 women. Lancet. 1992;339:71–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swedish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group. Randomized trial for two versus five years of adjuvant tamoxifen for postmenopausal early stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:1543–1549. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.21.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Current Trials Working Party Cancer Research Campaign Breast Cancer Trials Group. Preliminary results from the Cancer Research Campaign trial evaluating tamoxifen duration in women aged fifty years or older with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:1834–1839. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.24.1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cuzick J, Baum M. Tamoxifen and contralateral breast cancer. Lancet. 1985;i:282. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90338-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Tamoxifen for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 1998;351:1451–1467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nissen-Meyer R, Kjellgren K, Malmio K, Mansson B, Norin T. Surgical adjuvant chemotherapy: results with one short course with cyclophosphamide after mastectomy for breast cancer. Cancer. 1978;41:2088–2098. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197806)41:6<2088::aid-cncr2820410604>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baum M, Houghton J, Riley D. Results of the Cancer Research Campaign adjuvant trial for perioperative cyclophosphamide and long-term tamoxifen in early breast cancer reported at the tenth year of follow-up. Acta Oncol. 1992;31:251–257. doi: 10.3109/02841869209088911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher B, Carbone P, Economou SG. L-phenylalanine mustard (L-pam) in the management of primary breast cancer: a report of early findings. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:117–122. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197501162920301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonadonna G, Rossi A, Valagussa P. Adjuvant CMF chemotherapy in operable breast cancer: ten years later. Lancet. 1985;i:976–977. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91740-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubens RD, Bulbrook RD, Wang DY. The effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on endocrine function in patients with operable breast cancer. In: Salmon S, Jones S, editors. Adjuvant therapy of cancer. Amsterdam: Elsevier/North-Holland Biomedical Press; 1977. pp. 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Polychemotherapy for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 1998;352:930–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scholl SM, Asselain B, Palangie T, Dorval T, Jouve M, Garcia-Giralt E, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in operable breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1991;27:1668–1671. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(91)90442-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonadonna G, Valagussa P, Brambilla C, Moliterni A, Zambetti M, Ferrari L. Adjuvant and neoadjuvant treatment of breast cancer with chemotherapy and/or endocrine therapy. Semin Oncol. 1991;18:515–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mamounas EP. Overview of national surgical adjuvant breast project neoadjuvant chemotherapy studies. Semin Oncol. 1998;25:31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beral V, Hermon C, Reeves G. Sudden fall in breast cancer death rates in England and Wales. Lancet. 1995;345:1642–1643. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]