INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant neoplasm characterized by the clonal proliferation of plasma cells within the bone marrow, leading to the overproduction of monoclonal immunoglobulins.1 It is a relatively rare malignancy, with an annual incidence rate of 7.1 cases per 100,000 people.2 MM predominately occurs among the elderly, with a median age of 69 years and displays a higher incidence among males.3 Despite advancements in treatment modalities, MM remains an incurable disease, necessitating ongoing research into novel therapeutic strategies. 4 This case report highlights the unexpected diagnosis of MM in a patient who initially presented to a hospital with a pericardial effusion.

CASE REPORT

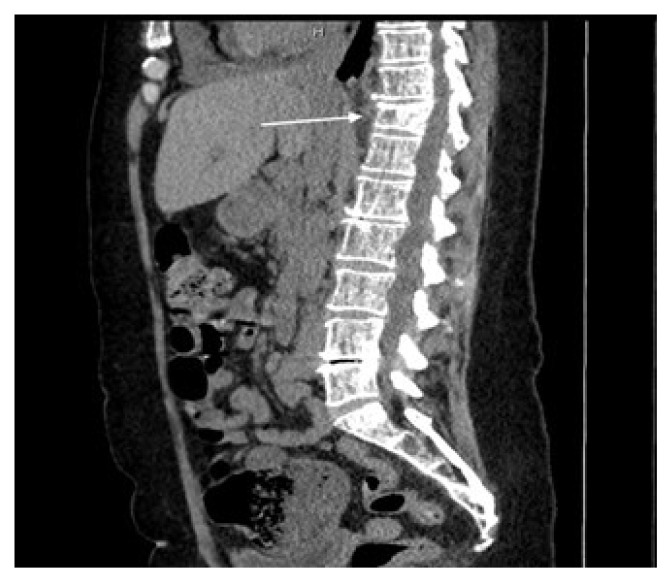

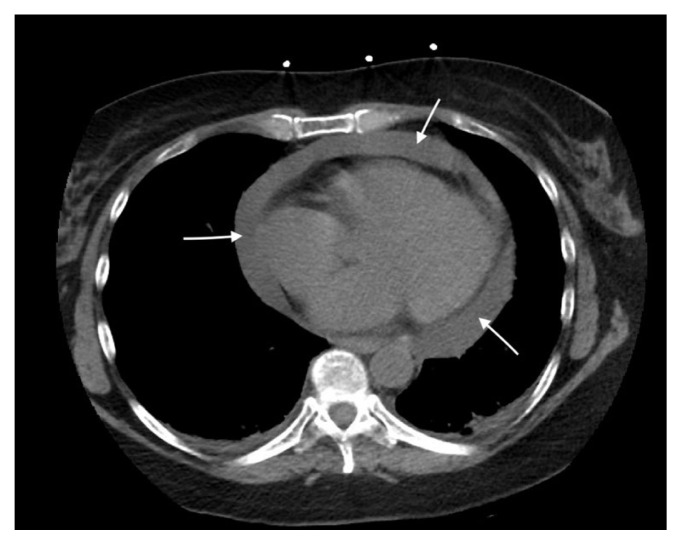

A 54-year-old female with a past medical history of cutaneous lupus erythematous, presented to the emergency department (ED) complaining of severe right upper quadrant abdominal pain radiating to her back for the last three weeks. The patient was noted to have a low hemoglobin (Hgb) of 7.4 gm/dl (12–16gm/dl), high creatinine (Cr) of 1.67 mg/dl (0.6–1.0 mg/dl), elevated calcium (Ca) of 10.3 mg/ dl (8.5–10.1 mg/dl), and an elevated serum total protein level of 11.9 gm/dl (6.4–8.2 gm/dl). Ultrasound of the liver and gallbladder showed mild hepatomegaly, with no sign of cholelithiasis or acute cholecystitis, which was of primary concern to the patient upon presentation to the ED. A follow-up computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis without contrast was completed, which showed a T11 compression fracture (Figure 1) and a large pericardial effusion with a maximal depth of 3.3 cm (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

T11 compression fracture.

Figure 2.

Pericardial effusion, max depth 3.3 cm.

Given the persistent upper abdominal pain, along with the CT findings of a large pericardial effusion, a stat echocardiogram was ordered, and a pericardial window was scheduled for the following day. Upon completion of the procedure, the patient reported that her upper abdominal pain was resolving, and she was feeling better. Despite these positive reports, the patient was noted to have persistent hypercalcemia with calcium at a level of 12.3 mg/dl (8.5–10.1 mg/dl) and ionized Ca at 6.8 mg/dl (4.5–5.3 mg/dl), as well as anemia with Hgb at 8.2 gm/dl (12–16 gm/dl), and an acute kidney injury with Cr at 1.26 mg/dl (0.6–1.0 mg/dl). The patient exhibited symptoms of hypercalcemia, including constipation, extremity paresthesia, frequent urination, and persistent thirst. Due to these symptoms, along with laboratory reports, concurrent back pain, an established T11 compression fracture, and other findings commonly seen in MM patients (Table 1), a workup for this disease process was initiated.

Table 1.

Common signs and symptoms of multiple myeloma.5

| Signs and Symptoms | Incidence, % |

|---|---|

| Anemia | 73 |

| Bone pain (generally severe and provoked by movement) | 58 |

| Elevated creatinine | 48 |

| Fatigue/generalized weakness | 3 |

| Hypercalcemia | 28 |

| Pathologic fracture | 26–34 |

| Weight loss | 24 |

| Paresthesias | 5 |

| Hepatomegaly | 4 |

| Splenomegaly | 1 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 1 |

| Fever | 0.7 |

A peripheral blood smear was completed first, which showed 2 plus rouleau formation within the specimen. Serum protein electrophoresis with monoclonal protein was ordered, along with kappa/lambda light chains. IgG monoclonal protein was seen on immunofixation (IgG 5672 mg/dl Normal: 586–1602 mg/dl) with a lambda light chain specificity (K/L ratio of 0.03, Normal ratio 0.26–1.65). Upon receiving these lab reports, a bone marrow biopsy was conducted, which revealed diffuse hypercellularity of the bone marrow, with up to 70% tumor burden of clonal malignant plasma cells within the specimen. Given these findings, a diagnosis of MM was made based off the updated MM diagnostic criteria (Table 2). At this time the patient was noted to have a significantly altered mental status with hallucinations, which was attributed to hypercalcemia and hospital-induced delirium. Her mental status improved significantly with management of the hypercalcemia. The patient completed her first course of chemotherapy in the hospital and was scheduled to continue with outpatient treatment at a community hematology/oncology clinic.

Table 2.

Multiple myeloma diagnostic criteria.6

| Both criteria must be met: |

|---|

|

DISCUSSION

Etiologically, MM is thought to arise from genetic abnormalities, particularly chromosomal translocations involving chromosome 14.7 The aberrant proliferation of plasma cells disrupts the delicate balance within the bone marrow microenvironment, causing bone destruction, anemia, hypercalcemia, and renal impairment.8 The patient presented with lab abnormalities consistent with bone marrow aberrancy, but she was much younger than the usual median age for MM (69 years) diagnosis.

While MM patients can be asymptomatic, the two most common presenting symptoms are fatigue and bone pain.9 Hyperviscosity can also be an issue due to the altered makeup of the vascular environment with some patients ending up with pulmonary emboli or ischemic strokes.10 Hypercalcemia symptoms, such as constipation, nausea, vomiting, psychosis, and increased thirst and urination, also can manifest after the lytic bone process has taken place. While the patient manifested some of the above symptomatology later in her hospital stay, her only complaint upon admission to the ED was radiating upper abdominal pain, which was an unusual disease presentation.

This unusual disease presentation was eventually attributed to this patient’s pericardial effusion. MM can be a rare cause of pericardial effusion and if MM is suspected to be the cause of the effusion, this can be determined by identifying plasma cells in the pericardial fluid and within the pericardial biopsy specimen itself.11,12 While this patient presented with a pericardial effusion prior to the eventual diagnosis of MM, the final etiology of the effusion was determined to be idiopathic, as no plasma cells were noted on cytology of the pericardial fluid, and no other inflammatory infiltrates were seen within the pericardium itself. However, it is worth noting that the sensitivity of detecting malignancy on pericardial fluid has been found to be approximately 70% and as such there is a sizable possibility of a false negative result.13

After a diagnosis of MM has been made based on lab results and symptomatology, the five-year survival of this disease is 57%.14 Age is one of the most influential factors in this disease process as those older than 66 years have a significant decrease in overall survival compared to younger individuals.15 Cytogenetic proliferation index, as well as other intrinsic properties like cellular characteristics of the tumor cells themselves, also play a significant role.16 Hypoalbuminemia and AKI were both noted during lab evaluation of this patient; both of these are independent negative prognostic indicators for MM.17,18 In this patient’s case, her younger age at diagnosis may allow for longer survival and more prompt and effective response to treatment.

Treatment regimens vary mildly between cases, depending on practice preference and response rates. One primary facet of care that must be addressed is the hypercalcemic response seen among MM patients from the destruction of bone due to the lytic myeloma lesions. For this, isotonic saline and bisphosphonates are mainstays of treatment in the reduction of the osteoclastic response.19 This patient received both treatments, and a reduction in excess urination, constipation, and confusion were noted.

Once symptomatic treatment has been disseminated, goal-directed therapy can be the focus. MM therapy is dominated by three drug regimens such as Bortezomib cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone (VCD), which was the initial regimen given to this patient during hospitalization. This is typically given in cycles of four, with subsequent autologous stem cell transplant (ASTC) to follow. Ineligibility criteria for ASTC include exclusion parameters such as patients older than 77 years, those with cirrhosis, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 3 or 4, or New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure.20 Although remission can be achieved through this therapeutic regimen, no current cure exists. Further research must be done into new therapeutic approaches with the hope of not only inducing remission but curing the patient of disease.

In conclusion, this case involved a unique blend of presenting characteristics in a patient with MM. MM does not always present with a clear symptomatology, which is exemplified by this case where the patient was much younger than the median age at presentation and presented due to symptoms stemming from a pericardial effusion of an ultimately unknown source.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hultcrantz M, Morgan GJ, Landgren O. Epidemiology and Pathophysiology of Multiple Myeloma. In: Dimopoulos M, Facon T, Terpos E, editors. Multiple Myeloma and Other Plasma Cell Neoplasms. Springer; 2018. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Myeloma - Cancer Stat Facts. 2024. [Accessed March 25, 2024]. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/mulmy.html .

- 3.Padala SA, Barsouk A, Barsouk A, et al. Epidemiology, staging, and management of multiple myeloma. Med Sci (Basel) 2021;9(1):3. doi: 10.3390/medsci9010003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez-Otero P, Paiva B, San-Miguel JF. Roadmap to cure multiple myeloma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2021;100:102284. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2021.102284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang H, Bazerbachi F, Mesa H, Gupta P. Asymptomatic multiple myeloma presenting as a nodular hepatic lesion: A case report and review of the literature. Ochsner J. 2015;15(4):457–467. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):e538–548. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fonseca R, Barlogie B, Bataille R, et al. Genetics and cytogenetics of multiple myeloma: A workshop report. Cancer Res. 2004;64(4):1546–1558. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fairfield H, Falank C, Avery L, Reagan MR. Multiple myeloma in the marrow: Pathogenesis and treatments. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016;1364(1):32–51. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajkumar SV, Kumar S. Multiple myeloma: Diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(1):101–119. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Debureaux PE, Harel S, Parquet N, et al. Prognosis of hyperviscosity syndrome in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma in modern-era therapy: A real-life study. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1069360. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1069360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samuels LE, Van PY, Gladstone DE, Haber MM. Malignant pericardial effusion--an uncommon complication of multiple myeloma: Case report. Heart Surg Forum. 2005;8(2):E87–88. doi: 10.1532/HSF98.20041153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garg S, King G, Morginstin M. Malignant pericardial effusion: An unusual presentation of multiple myeloma. Clinical Microbiology & Case Reports. 2015;2(1):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dragoescu EA, Liu L. Pericardial fluid cytology: An analysis of 128 specimens over a 6-year period. Cancer Cytopathol. 2013;121(5):242–251. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Cancer Society. Survival Rates for Multiple Myeloma. Mar 2, 2023. [Accessed March 25, 2024]. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/multiple-myeloma/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html .

- 15.Chretien ML, Hebraud B, Cances-Lauwers V, et al. Age is a prognostic factor even among patients with multiple myeloma younger than 66 years treated with high-dose melphalan: The IFM experience on 2316 patients. Haematologica. 2014;99(7):1236–1238. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.098608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corre J, Munshi NC, Avet-Loiseau H. Risk factors in multiple myeloma: Is it time for a revision? Blood. 2021;137(1):16–19. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019004309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen YH, Magalhaes MC. Hypoalbuminemia in patients with multiple myeloma. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150(3):605–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sprangers B. Aetiology and management of acute kidney injury in multiple myeloma. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33(5):722–724. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfy079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oyajobi BO. Multiple myeloma/hypercalcemia. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(Suppl 1):S4. doi: 10.1186/ar2168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albagoush SA, Shumway C, Azevedo AM. StatPearls [Internet] Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Jan 30, 2024. Jan 30, Multiple Myeloma. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]