Abstract

College campuses in the United States are experiencing high levels of mental distress without adequate psychological resources to address the need. In addition, the majority of university students do not meet the physical activity guidelines for mental and physical health. Effective and time efficient resources are needed to address poor mental health and low physical activity among university students on college campuses. Mindful walking may be a promising solution. The purpose was to 1) measure change in mental health and 2) estimate physical activity from participation in a guided mindful walk in a diverse student sample. Students participated in a mindful walking route which included seven stops (0.85 miles) during the Spring 2022 semester. Undergraduate students (n = 44) were mean ± SD age 20.9 ± 3.8 years and 68% female. Validated surveys were given pre- and post-participation measuring mental health constructs of state mindfulness (Toronto Mindfulness Scale; TMS), state anxiety (visual analogue scale), and state stress (Short Stress State Questionnaire; SSSQ). Physical activity was estimated via steps on a Yamax pedometer worn at the hip. After the guided mindful walk, total state mindfulness score significantly improved (mean ± SD) (pre: 27.5 ± 8.2, post: 32.8 ± 9.5; p < 0.001); state anxiety significantly decreased (pre: 3.7 ± 2.4, post: 2.4 ± 2; p < 0.0001) and total state stress score was reduced (pre: 66.1 ± 10.7, post: 63.4 ± 8.3; p = 0.03). Physical activity averaged 1,726 ± 159 steps. Completion of a guided mindful walk can reduce anxiety and stress, while increasing mindfulness among university students.

Keywords: Mindfulness, walking, stress, anxiety, health promotion, mind-body exercise, outdoor exercise, stress reduction, student wellness, well-being

INTRODUCTION

Despite the known benefits of physical activity, only 46.9% of American adults get the recommended levels of aerobic physical activity of 150 minutes per week of at least moderate intensity physical activity (14). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has decreased physical activity and increased sedentary time (7, 24, 25). Low levels of physical activity and increased sedentary behavior can negatively impact physical health by increasing risk for obesity, cardiovascular disease and diabetes while also negatively influencing mental health such as increasing anxiety, depression, stress, and loneliness (7, 19, 23, 24, 26, 29). In addition, the percentage of adults in the United States reporting symptoms of anxiety or a depressive disorder during the pandemic rose from 36.4% to 41.5%, with the largest increases seen in adults aged 18–29 years old, making university-aged students especially susceptible to mental health issues (42).

Mindfulness is characterized by a nonjudgmental awareness of and attention to moment-by-moment cognition, emotion, and sensation without fixation on thoughts of past and future (18). Mindfulness practices are meant to be deliberate, intentional, and involve paying attention to the present moment non-reactively (18). Mindfulness practice may be one technique that can be used to improve mental and physical health (18). Increasing a person’s mindfulness has been shown to be associated with decreased stress and improvements in anxiety, eating, sleeping, and physical health (5, 9, 28, 33).

Research has shown there is a correlation between mindfulness and physical activity, and that combining mindfulness approaches with physical activity has been successful in improving both mental and physical health (3, 39, 44). A recent systematic review highlights the promising effects of meditative and mindful walking on aspects of mental and cardiovascular health (i.e. anxiety, depression, state mindfulness, stress, blood pressure) (11). Further, mindful walking occurring outdoors has shown positive effects in mood (31). A previous study in adults with low physical activity levels has shown that a mindful walking intervention significantly improved perceived stress, physical activity, and depression, but this study did not look specifically at young adults (38). One study in young adults that compared a short bout of walking and meditation found significant reductions in state anxiety when walking and meditation were done sequentially (13). However, this study did not investigate simultaneous meditation and walking or measure other constructs of state mental health such as mindfulness or stress. Changes in state constructs of mindfulness (i.e. patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving at a specific moment in time) can lead to changes in trait constructs of mindfulness (i.e. patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving that remain stable across time) (36). An eight-week mindfulness-based intervention found that increases in state mindfulness resulted in increases in trait mindfulness (21). Thus, an acute intervention aimed at enhancing state mindfulness may also have the potential to positively affect trait mindfulness. Further, some previous interventions have been multiple weeks in length, which may not be well suited for a university student where time is a barrier, highlighting the need for a single acute intervention (15, 38, 40). A systematic review and meta-analysis found results supporting the effects of a single session of mindful exercise (i.e. yoga, Tai chi, Qigong) on reducing anxiety, but did not include mindful walking in the review, underscoring the need to study the effects of acute sessions of mindful walking (45). Another major barrier for college students is accessible places on campus even though it is known that the campus environment (i.e. access to facilities, events, and resources) can positively influence physical activity levels (15, 20). Thus, there is a need to evaluate the effectiveness of short, accessible, outdoor resources specific to university students within the campus environment to address both mental and physical health.

Therefore, the purpose was to 1) measure changes in mental health (state mindfulness, state anxiety, and state stress) and 2) measure physical activity (step count) from participation in a guided mindful walk in a diverse student sample. The hypothesis was that following the guided mindful walk, participants’ state mindfulness would increase, while state stress and state anxiety would decrease.

METHODS

In Fall 2021, a pilot study was conducted in a group of Kinesiology students (n = 33) at the University of San Francisco (USF). Preliminary results found that after the guided mindful walk, state stress significantly decreased (score pre-to-post: −3.1 ± 6.7, p = 0.01) and state anxiety significantly decreased (score pre-post: −1.5 ± 1.5, p < 0.0001). To achieve a power of 80% and a level of significance of 5% (two-sided), a minimum sample size of 39 was determined for the study for a significant change in state anxiety, and a minimum sample size of 11 was needed for a significant change in state stress (12). State mindfulness was added as an exploratory measure as a mechanism to explain changes in state anxiety and state stress (34). To estimate the power needed for significant change in state mindfulness, the hypothesized change was approximately +8.8 ± 8.8 (mean ± SD) based on previous research (22). This change requires 11 participants for 80% power (12). Thus, the sample size for our research was determined to be a minimum of n = 39 to have adequate power for all outcome variables: state mindfulness, state anxiety, and state stress.

Participants

Participants were recruited from two courses during the Fall 2022 semester: 1) Introduction to Kinesiology for Kinesiology majors, and 2) Introduction to Fitness and Wellness, a course for non-Kinesiology and non-science majors. Inclusion criteria included the following: 1) able to read and understand English, 2) had access to a mobile or computer device to answer online questions, and 3) at least 18 years of age. Exclusion criterion was as follows: 1) unable to safely and comfortably walk and stand for 25 minutes. All students participated in the mindful activity, but students had the option as to whether they wanted to be included in the research study. Students who opted into the research study provided written consent. Participants were not financially compensated or offered class credit for participating in the study. All protocols were approved by the University of San Francisco Institutional Review Board and carried out in full accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki as well as the ethical standards of the International Journal of Exercise Science (30).

Demographics such as race and ethnicity, age, sex, current physical activity level and mental health were self-reported via questionnaire. Participants were on average 20.9 ± 3.8 years (range 18–40 years). Participants reported engaging in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) on average 4.1 ± 1.8 days in the last seven days (range 1–7 days). Students reported spending an average of 91.6 ± 93.6 minutes in MVPA per day (range 20–450 minutes). The majority of the participants (n = 32; 72.7%) met the physical activity guidelines of at least 150 minutes MVPA per week. Approximately 25% of the participants reported having a diagnosed mental health illness (i.e., anxiety, mood disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder). Student participants were majority female while race, ethnicity and year in school were diverse, representing Hispanic/Latino, Asian, White, Black/African American, and Mixed categories, as well as representing each year in school (i.e., Freshman, Sophomore, Junior, Senior). See Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants (n = 44).

| Variable | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 30 | 68.2 | |

| Male | 14 | 31.8 | |

| Other (e.g. “intersex”) | 0 | 0 | |

| Race and Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 15 | 34.1 | |

| Asian | 11 | 25.0 | |

| White | 11 | 25.0 | |

| Black/African American | 6 | 13.6 | |

| Other/Mixed | 1 | 2.3 | |

| Year in school | |||

| Freshman | 14 | 31.8 | |

| Sophomore | 4 | 9.1 | |

| Junior | 15 | 34.1 | |

| Senior | 11 | 25.0 | |

| Undergraduate major | |||

| Science | Kinesiology | 18 | 41.0 |

| Business | Marketing, Finance | 10 | 22.7 |

| Social Science | Psychology, Sociology, Politics, History, Critical Diversity | 10 | 22.7 |

| Art | Performing Arts, Communications, Media | 6 | 13.6 |

| Diagnosed mental illness (i.e., anxiety, mood disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder) | Yes | 11 | 25.0 |

| No | 33 | 75.0 | |

Protocol

The guided mindful walking route included themes from USF alumnus Hal Urban’s book, The Power of Good News: Feeding Your Mind with What’s Good for Your Heart (41). The guided mindful walk included seven stops that asked participants to stop, reflect, notice their current surroundings, use their senses, and focus on the present moment. Example themes and topics included gratitude, reframing, balance, and nourishment. Reflection questions related to the theme were also presented at each stop (i.e. How can I reframe my perspective? How can I nourish my mind, body and spirit with good news?) (https://usfblogs.usfca.edu/urbantrail/). The 0.85-mile route was created to be tailored specifically to the USF campus. The guided mindful walk purposefully included prominent sculptures, art installations, and outdoor spaces on campus, in an attempt to make the route relevant and meaningful for the students who participated in the study. The route was also made more accessible by not including crosswalks or stairs and all stops were located outside on campus making it available any time of day. To provide consistency in the delivery of the guided mindful walk content, students were led in a group of about ~20–25 individuals by the same professor during their regular class time. The delivery of the information included a written script presented orally to the students explaining the purpose of the mindful walk with an accompanying flipbook containing quotes and images related to the content. Participants were encouraged to interact with each other (i.e. discussion regarding theme and reflection question at each stop) and were reminded to walk briskly between stops. Prior to the current research study on the health effects, a separate program evaluation was performed (n = 124 participants) to attain feedback on the acceptability, accessibility, enjoyment, fidelity, and reach during 18 separate walks. The average walk took 34.8 minutes (range: 25–45 mins) (unpublished).

Participants completed validated surveys pre- and post-walk on the guided mindful walk to evaluate any potential changes in state mental health. The Toronto Mindfulness Scale (TMS) contained 13 items measuring curiosity and decentering on a 0–4 Likert scale (0 = “Not at all”; 4 = “Very Much”) (22). State anxiety was measured using a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and score 1–10 (10 = greatest anxiety) (10). The Short Stress State Questionnaire (SSSQ) was comprised of 24 items measuring worry, distress, and task engagement on a 1–5 Likert scale (1 = “Not at all”; 5 = “Extremely”) (17).

To estimate physical activity, participants wore a Yamax pedometer (YAMASA TOKEI KEIKI CO., LTD., 2-4-9, Kaminoge, Setagaya-ku, Tokyo, 158-0093, Japan) at the hip during the guided mindful walk. Self-reported physical activity was assessed at baseline only via the Physical Activity Vital Sign (PAVS) which asked how many minutes and days per week a participant engages in moderate (i.e., brisk walk) to strenuous physical activity (i.e., run) (35). The frequency and duration/time was then multiplied out to determine minutes per week of MVPA. Any person who had at least 150 minutes per week of MVPA was labeled as meeting the physical activity guidelines (4).

Statistical Analysis

Changes in state mental health variables were explored using paired samples t-tests for normally distributed variables (mindfulness, stress) and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for nonnormally distributed variables (anxiety) using Microsoft Excel version 16.70 (Microsoft Corporation, One Microsoft Way, Redmond, WA, 98052-6399, United States). All data are presented as means ± SD unless otherwise noted in the text or table. The α level was set at 0.05. Cohen’s d effect sizes were also calculated for all mental health variables measured (0.2 = small, 0.5 = medium, 0.8 = large) (8). One participant’s data has been omitted from curiosity and total state mindfulness calculations due to incomplete survey data.

RESULTS

Following the guided mindful walk, there were significant increases in state mindfulness score (t(42) = −4.83, 95% CI 3.14 to 7.42, p < 0.0001, Cohen’s d = 0.74), significant decreases in total scores for state anxiety (W = 0, 95% CI −1.63 to −1.01, p < 0.0001, Cohen’s d = 1.26), and significant decreases in state stress scores (t(43) = 2.26, 95% CI −4.97 to −0.35, p = 0.03, Cohen’s d = 0.34). See Table 2.

Table 2.

Mental health changes pre and post (mean ± SD) guided mindful walk (n = 44).

| Variable | Scale | Pre Total Score | Post Total Score | Difference Post — Pre | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State Mindfulness | TMS | 27.53 ± 8.17 | 32.81 ± 9.50 | +5.28 ± 7.17 | < 0.0001* |

| State Anxiety | VAS | 3.68 ± 2.42 | 2.36 ± 1.99 | −1.32 ± 1.05 | < 0.0001* |

| State Stress | SSSQ | 66.07 ± 10.69 | 63.41 ± 8.27 | −2.66 ± 7.81 | 0.03* |

Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scoring: 1–10; Short Stress State Questionnaire (SSSQ) scoring: min = 24, max = 120; Toronto Mindfulness Scale (TMS) scoring: min = 0, max = 52. Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference of p < 0.05.

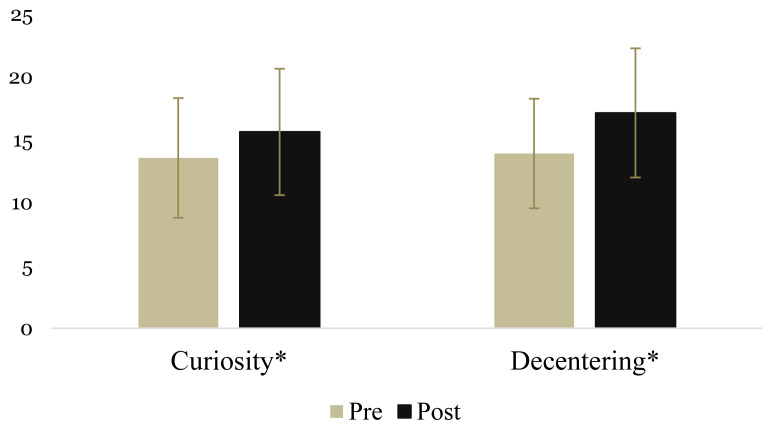

The TMS measured subscores of state mindfulness: curiosity and decentering. Figure 1 contains the results pre- and post-questionnaire following the guided mindful walk. Pre-scores for curiosity were 13.56 (95% CI: 12.15 to 14.97), while post-walk scores were 15.63 (95% CI: 14.14 to 17.12), the difference being +2.07 (95% CI: 0.81 to 3.33; t(42) = −3.21, p = 0.003, Cohen’s d = 0.49). Pre-scores for decentering were 13.91 (95% CI: 12.62 to 15.20), post-scores were 17.14 (95% CI: 15.62 to 18.66), and the difference was +3.23 (95% CI 2.05 to 4.41; t(43) = −5.35, p < 0.0001, Cohen’s d=0.81).

Figure 1.

Change in state mindfulness subscores from the Toronto Mindfulness Scale (TMS) after a guided mindful walk (mean ± SD). Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference of p < 0.05.

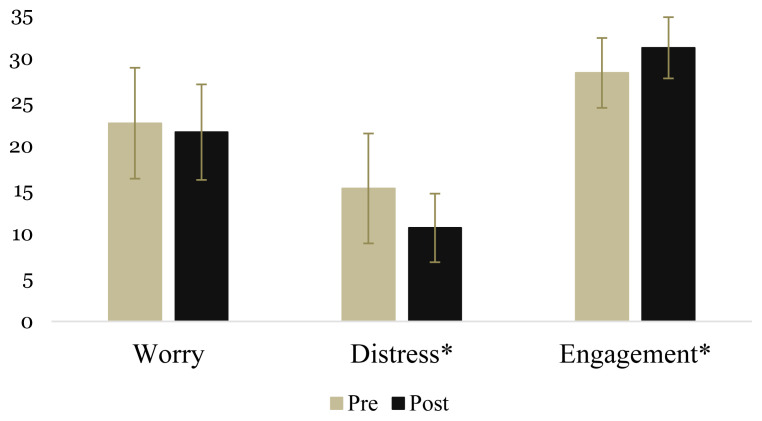

The SSSQ measured subscores of state stress: worry, distress, and engagement. Figure 2 contains the results from the stress subscores before and immediately after the guided mindful walk. Pre-walk worry scores were 22.59 (95% CI: 20.70 to 24.48), while post-walk scores were 21.57 (95% CI: 19.94 to 23.20). The pre- to post- difference for worry scores was −1.02 95% CI: −2.54 to 0.50 (W = 309, p = 0.38, Cohen’s d = 0.20). Pre-walk distress scores were 15.16 (95% CI: 13.31 to 17.01), while post-walk distress scores were 10.66 (95% CI: 9.50 to 11.82). The difference for the distress score was −4.50 (95% CI: −5.75 to −3.25, W=11.5, p < 0.0001, Cohen’s d = 1.07). Pre-scores for engagement were 28.32 (95% CI: 27.14 to 29.50), while post- engagement scores were 31.18 (95% CI: 30.15 to 32.21), a difference of +2.86 (95% CI: 1.78 to 3.94, t(43) = −5.18, p < 0.0001, Cohen’s d = 0.78).

Figure 2.

Change in state stress subscores from the Short Stress State Questionnaire (SSSQ) after a guided mindful walk (mean ± SD). Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference of p < 0.05.

For physical activity, students walked on average 1,726 ± 159 steps during the guided mindful walk.

DISCUSSION

In summary, university students engaging in a guided mindful walk significantly increased state mindfulness, significantly reduced state anxiety, and significantly reduced state stress.

For state mindfulness, there were significant increases in both subscores for curiosity and decentering. Effect sizes were medium for curiosity (Cohen’s d = 0.49), large for decentering (Cohen’s d = 0.81), and medium for overall state mindfulness (Cohen’s d = 0.74). The TMS measure assessed awareness of the present moment (curiosity) without being carried away by one’s thoughts and emotions (decentering) (22). These findings are consistent with previous research on the effect of a nature walk enhancing mindfulness. Mindful walking and related activities in nature (i.e. yoga) have been shown by Gotink et al. to increase mindfulness; however, the previous research varied in length of time from 1–10 days and was combined with other activities, making it difficult to attribute the effect from the mindful walking alone (16). Our research study examined the effects of a single bout of mindful walking on state mindfulness. Our findings also support the improvements in state mindfulness among university students reported by Bigliassi et al. following an acute walking session (2). Bigliassi et al. found that 4–6 minute mindfulness meditation walking bouts outside improved aspects of mindfulness related to affect and attention (2). Our study focused on mindful walking and the environment to reduce anxiety and stress, while the previous study involved meditation specific to not only the environment, but also sensations of the feet and legs. Our results are in agreement with a previous systematic review’s findings that engaging in mindful walking enhances state mindfulness, even after a single session (11).

Following the guided mindful walk, there was a significant decrease in state anxiety, with a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 1.26). The findings from our present study support previous research that a single bout of walking and meditation can decrease state anxiety in young adults (13). Though Edwards et al. did not examine the effects of simultaneous walking and meditation, our findings show that combined mindfulness and walking is an effective way to reduce state anxiety in university students (13). Our results also support previous findings from Call et al. that mindfulness practice can decrease anxiety in undergraduate students (6). However, our research adds that mindfulness practice in combination with walking can decrease state anxiety after a single session, compared to Call et al.’s protocol of weekly 45 minute sessions (6).

When examining our state stress score in more detail, our study showed significant reductions in the subscores for distress and significant increases in engagement. The worry subscore was reduced in magnitude, but the amount was not statistically significant. Effect sizes were large for distress (Cohen’s d = 1.07), small for worry (Cohen’s d = 0.20), large for engagement (Cohen’s d = 0.78), and small for overall state stress (Cohen’s d = 0.34). The SSSQ value was a composite measure of the interaction between negative affect (distress), cognition and self-focused attention (worry), and motivation and confidence (engagement) (17). Thus, our guided mindful walk showed significant decreases in certain aspects of negative stress and increases in positive stress. Mixed results have been shown in a systematic review conducted by Morton et al. on the effect of brief mindfulness interventions on stress, though the studies included were meditation-based rather than mindful walking (27). Our findings support previous research on reducing stress through mindful-based activities in undergraduate students (6).

A potential mechanism to explain the findings may involve increasing intention, attention, and openness/non-judgmentalness (components of mindfulness) lead to the experience of reperceiving or a shifting of one’s perspective (37). Reperceiving an event with a curious lens and decentering from the current experience allows a participant to have positive outcomes such as reduced stress and anxiety (37, 43).

Not only can walking improve mental health, but walking can also increase physical activity levels. Adding ~1,700 more steps into a student’s day is an important strategy to add overall physical activity to help meet the physical activity recommendations. An average adult takes 5,117 steps per day (1). Adding in ~1,700 steps would bring students closer to reaching the goal of 8,000–10,000 steps per day to decrease all-cause mortality risk for this age group (32). As previously mentioned, the walk takes an average of ~35 mins to complete. This may be an especially relevant strategy for university students to use, offering a reasonably short activity to lower stress and anxiety and enhance mindfulness. Studies have shown that mindful walking can enhance mindfulness even in students with low intrinsic motivation to exercise (9). This is especially pertinent on a college campus where time and motivation are common barriers for participation (15).

A major strength of this study is the use of validated questionnaires for state stress, state anxiety, and state mindfulness. Some of the current study’s weaknesses include being conducted on a single university campus and only in undergraduate students. Thus, the ability to extrapolate results to other student populations may be limited, and future studies are needed to show whether results are consistent in non-student groups such as faculty, staff or community members. Students were also recruited from classes related to physical activity and wellness and the majority of students (n = 32; 72.7%) met the physical activity guidelines for weekly MVPA, which could have resulted in a biased sample. In addition, previous experience with mindfulness was not collected from the sample and could be a limitation to the study if participants had either prior mindfulness experience or did not prefer mindfulness. However, our sample was incredibly diverse in the range of class (i.e., freshman, sophomore), majors, race and ethnicity which helps to generalize results to a more diverse group of students. To reduce response bias and/or recall bias, hypotheses were not discussed, all questionnaires were done online, and data collection and analysis were done by different research staff. In addition, while everyone participated in the guided mindful walk together, there was no course credit associated with the activity. The guided mindful walk created for this research project was free and accessible for anyone to engage, but was also tailored specifically to the features on the campus which may limit the ability to scale this mindfulness strategy to other universities. Future studies are needed to see whether this concept can be adapted to other university campuses to replicate health results. The current format of the walk was in a guided group setting at a scheduled time which may limit participation. Future studies should also explore the adaptation of this guided walk into a self-guided format that students can access at any time in order to widen reach.

In conclusion, a guided mindful walk can reduce state anxiety and state stress, while increasing state mindfulness and physical activity among university students. Results from the present study suggest that among university students, guided mindful walking has positive effects on state mental health variables including mindfulness, anxiety, and stress.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding given by the Jesuit Foundation Grant and the University of San Francisco Faculty Development Funds.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bassett DR, Jr, Wyatt HR, Thompson H, Peters JC, Hill JO. Pedometer-measured physical activity and health behaviors in U.S. adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(10):1819–1825. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181dc2e54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bigliassi M, Galano BM, Lima-Silva AE, Bertuzzi R. Effects of mindfulness on psychological and psychophysiological responses during self-paced walking. Psychophysiology. 2020;57(4):e13529. doi: 10.1111/psyp.13529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blair Kennedy A, Resnick PB. Mindfulness and physical activity. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2015;9(3):221–223. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G, Carty C, Chaput JP, Chastin S, Chou R, Dempsey PC, DiPietro L, Ekelund U, Firth J, Friedenreich CM, Garcia L, Gichu M, Jago R, Katzmarzyk PT, Lambert E, Leitzmann M, Milton K, Ortega FB, Ranasinghe C, Stamatakis E, Tiedemann A, Troiano RP, van der Ploeg HP, Wari V, Willumsen JF. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(24):1451–1462. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burton A, Burgess C, Dean S, Koutsopoulou GZ, Hugh-Jones S. How effective are mindfulness-based interventions for reducing stress among healthcare professionals? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stress Health. 2017;33(1):3–13. doi: 10.1002/smi.2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Call D, Miron L, Orcutt H. Effectiveness of brief mindfulness techniques in reducing symptoms of anxiety and stress. Mindfulness. 2014;5(6):658–668. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheval B, Sivaramakrishnan H, Maltagliati S, Fessler L, Forestier C, Sarrazin P, Orsholits D, Chalabaev A, Sander D, Ntoumanis N, Boisgontier MP. Relationships between changes in self-reported physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and health during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in France and Switzerland. J Sports Sci. 2021;39(6):699–704. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2020.1841396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox AE, Roberts MA, Cates HL, McMahon AK. Mindfulness and affective responses to treadmill walking in individuals with low intrinsic motivation to exercise. Int J Exerc Sci. 2018;11(5):609–624. doi: 10.70252/AEVJ8865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davey HM, Barratt AL, Butow PN, Deeks JJ. A one-item question with a Likert or visual analog scale adequately measured current anxiety. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(4):356–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis DW, Carrier B, Cruz K, Barrios B, Landers MR, Navalta JW. A systematic review of the effects of meditative and mindful walking on mental and cardiovascular health. Int J Exerc Sci. 2022;15(2):1692–1734. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhand NK, Khatkar MS. Statulator: An online statistical calculator. Sample size calculator for comparing two paired means. 2014. Retrieved from http://statulator.com/SampleSize/ss2PM.html.

- 13.Edwards MK, Rosenbaum S, Loprinzi PD. Differential experimental effects of a short bout of walking, meditation, or combination of walking and meditation on state anxiety among young adults. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32(4):949–958. doi: 10.1177/0890117117744913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elgaddal N, Kramarow EA, Reuben C. Physical activity among adults aged 18 and over: United States, 2020. NCHS Data Brief. 2022;443(12):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferreira Silva RM, Mendonca CR, Azevedo VD, Raoof Memon A, Noll P, Noll M. Barriers to high school and university students’ physical activity: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2022;17(4):e0265913. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0265913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gotink RA, Hermans KS, Geschwind N, De Nooij R, De Groot WT, Speckens AE. Mindfulness and mood stimulate each other in an upward spiral: A mindful walking intervention using experience sampling. Mindfulness. 2016;7(5):1114–1122. doi: 10.1007/s12671-016-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helton WS, Naswall K. Short stress state questionnaire: Factor structure and state change assessment. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2015;31(1):20–30. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness (Delta Trade Pbk. Reissue. Ed.). New York, NY: Delta Trade Paperbacks; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katzmarzyk PT, Powell KE, Jakicic JM, Troiano RP, Piercy K, Tennant B. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Sedentary behavior and health: Update from the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(6):1227–1241. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keating XD, Guan J, Pinero JC, Bridges DM. A meta-analysis of college students’ physical activity behaviors. J Am Coll Health. 2005;54(2):116–125. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.2.116-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiken LG, Garland EL, Bluth K, Palsson OS, Gaylord SA. From a state to a trait: Trajectories of state mindfulness in meditation during intervention predict changes in trait mindfulness. Pers Individ Dif. 2015;81:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lau MA, Bishop SR, Segal ZV, Buis T, Anderson ND, Carlson L, Shapiro S, Carmody J, Abbey S, Devins G. The Toronto Mindfulness Scale: Development and validation. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62(12):1445–1467. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee E, Kim Y. Effect of university students’ sedentary behavior on stress, anxiety, and depression. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2019;55(2):164–169. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lesser IA, Nienhuis CP. The impact of COVID-19 on physical activity behavior and well-being of Canadians. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):3899. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maugeri G, Castrogiovanni P, Battaglia G, Pippi R, D’Agata V, Palma A, Di Rosa M, Musumeci G. The impact of physical activity on psychological health during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Heliyon. 2020;6(6):e04315. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer J, McDowell C, Lansing J, Brower C, Smith L, Tully M, Herring M. Changes in physical activity and sedentary behavior in response to COVID-19 and their associations with mental health in 3052 US adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6469. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morton ML, Helminen EC, Felver JC. A systematic review of mindfulness interventions on psychological responses to acute stress. Mindfulness. 2020;11:2039–2054. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy MJ, Mermelstein LC, Edwards KM, Gidycz CA. The benefits of dispositional mindfulness in physical health: A longitudinal study of female college students. J Am Coll Health. 2012;60(5):341–348. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2011.629260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National College Health Assessment III. Reference group executive summary. 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.acha.org/documents/ncha/NCHAIII_SPRING_2023_REFERENCE_GROUP_EXECUTIVE_SUMMARY.pdf.

- 30.Navalta JW, Stone WJ, Lyons TS. Ethical issues relating to scientific discovery in exercise science. Int J Exerc Sci. 2019;12(1):1–8. doi: 10.70252/EYCD6235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nisbet EK, Zelenski JM, Grandpierre Z. Mindfulness in nature enhances connectedness and mood. Ecopsychology. 2019;11(2):81–91. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paluch AE, Bajpai S, Bassett DR, Carnethon MR, Ekelund U, Evenson KR, Galuska DA, Jefferis BJ, Kraus WE, Lee IM, Matthews CE, Omura JD, Patel AV, Pieper CF, Rees-Punia E, Dallmeier D, Klenk J, Whincup PH, Dooley EE, Pettee Gabriel K, Palta P, Pompeii LA, Chernofsky A, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Spartano N, Ballin M, Nordstrom P, Nordstrom A, Anderssen SA, Hansen BH, Cochrane JA, Dwyer T, Wang J, Ferrucci L, Liu F, Schrack J, Urbanek J, Saint-Maurice PF, Yamamoto N, Yoshitake Y, Newton RL, Jr, Yang S, Shiroma EJ, Fulton JE Steps for Health C. Daily steps and all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis of 15 international cohorts. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(3):e219–e228. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00302-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parmentier FBR, Garcia-Toro M, Garcia-Campayo J, Yanez AM, Andres P, Gili M. Mindfulness and symptoms of depression and anxiety in the general population: The mediating roles of worry, rumination, reappraisal, and suppression. Front Psychol. 2019;10(506):1–10. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts KC, Danoff-Burg S. Mindfulness and health behaviors: Is paying attention good for you? J Am Coll Health. 2010;59(3):165–173. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.484452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sallis RE, Matuszak JM, Baggish AL, Franklin BA, Chodzko-Zajko W, Fletcher BJ, Gregory A, Joy E, Matheson G, McBride P, Puffer JC, Trilk J, Williams J. Call to action on making physical activity assessment and prescription a medical standard of care. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2016;15(3):207–214. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmitt M, Blum GS. State/trait interactions. In: Zeigler-Hill V, Shackelford TK, editors. Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. New York, NY: Springer; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shapiro SL, Carlson LE, Astin JA, Freedman B. Mechansims of mindfulness. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62(3):373–386. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi L, Welsh RS, Lopes S, Rennert L, Chen L, Jones K, Zhang L, Crenshaw B, Wilson M, Zinzow H. A pilot study of mindful walking training on physical activity and health outcomes among adults with inadequate activity. Complement Ther Med. 2019;44:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strowger M, Kiken LG, Ramcharran K. Mindfulness meditation and physical activity: Evidence from 2012 National Health Interview Survey. Health Psychol. 2018;37(10):924–928. doi: 10.1037/hea0000656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teut M, Roesner EJ, Ortiz M, Reese F, Binting S, Roll S, Fischer HF, Michalsen A, Willich SN, Brinkhaus B. Mindful walking in psychologically distressed individuals: A randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:489856. doi: 10.1155/2013/489856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Urban H. The power of good news: Feeding your mind with what’s good for your heart. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vahratian A, Blumberg SJ, Terlizzi EP, Schiller JS. Symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder and use of mental health care among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic-United States, August 2020–February 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(13):490–494. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7013e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams KA, Kolar MM, Reger BE, Pearson JC. Evaluation of a wellness-based mindfulness stress reduction intervention: A controlled trial. Am J Health Promot. 2001;15(6):422–432. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-15.6.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang CH, Conroy DE. Momentary negative affect is lower during mindful movement than while sitting: An experience sampling study. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2018;37:109–116. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yin J, Tang L, Dishman RK. The effects of a single session of mindful exercise on anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ment Health Phys Act. 2021;21:100435. [Google Scholar]