Editor—The first article in the series on evidence based cardiology summarises evidence on the effect of antioxidant vitamins on the risk of cardiovascular disease.1 The summary of the trial evidence for vitamin C supplementation is, however, incomplete, and the authors’ interpretation of the available data on antioxidants is too optimistic.

The authors describe Wilson et al’s trial of vitamin C, in which 538 patients admitted to an acute geriatric unit were randomised to receive 200 mg of vitamin C or placebo daily for six months.2 We are aware of two further trials of vitamin C supplementation in Western populations that have reported on mortality from all causes. Burr et al randomised 297 elderly people with low vitamin C concentrations to receive vitamin C (150 mg a day for 12 weeks and 50 mg a day thereafter) or placebo for two years.3 Hunt et al randomised 199 elderly patients to receive 200 mg of vitamin C or placebo daily for six months.4

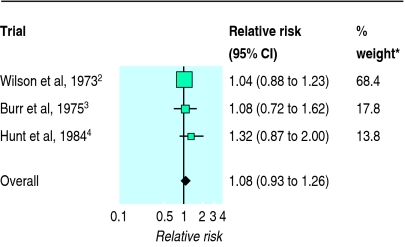

We performed a meta-analysis of all three trials using a fixed effects model (figure). Even though the three trials were small and relatively short, the combined results seem to exclude any substantial early benefit of vitamin C supplementation. The overall relative risk shows an increase in mortality of 8%, with the 95% confidence interval ranging from a 7% reduction to a 26% increase in mortality (P=0.29). An earlier meta-analysis of the β carotene trials also showed a moderate adverse effect, which was significant (P=0.005).5

Lonn and Yusuf argue that the strong biological rationale and observational epidemiological data relating antioxidants to lower cardiovascular risk justify ongoing trials. We believe that the disappointing results for vitamin C and β carotene should lead us to re-evaluate critically the status of the antioxidant hypothesis and to consider confounding as an alternative explanation for the lower cardiovascular risk observed in epidemiological studies.5

The ongoing trials of antioxidant vitamins should continue because we need to know whether vitamin supplements—widely used in preparations sold over the counter—produce any benefit or are in fact harmful. When potentially protective dietary constituents are identified in the future it may be more sensible to undertake trials of foods that are rich sources of these constituents rather than supplementation trials.

Figure.

Results of meta-analysis of three trials of vitamin C supplementation in elderly subjects, showing mortality from all causes. *Amount that each study contributes to pooled estimate of effect of vitamin C supplements.

References

- 1.Lonn E, Yusuf S. Emerging approaches in preventing cardiovascular disease. BMJ. 1999;318:1337–1341. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7194.1337. . (15 May.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson TS, Datta SB, Murrell JS, Andrews CT. Relation of vitamin C levels to mortality in a geriatric hospital: a study of the effect of vitamin C administration. Age Ageing. 1973;2:163–170. doi: 10.1093/ageing/2.3.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burr ML, Hurley RJ, Sweetnam PM. Vitamin C supplementation of old people with low blood levels. Gerontol Clin. 1975;17:236–243. doi: 10.1159/000245583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunt C, Chakkravorty NK, Annan G. The clinical and biochemical effects of vitamin C supplementation in short-stay hospitalized geriatric patients. Int J Vit Nutr Res. 1984;54:65–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egger M, Schneider M, Davey Smith G. Spurious precision? Meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 1998;316:140–145. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7125.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]