Abstract

A key limitation for the development of peptides as therapeutics is their lack of cell permeability. Recent work has shown that short, arginine-rich macrocyclic peptides containing hydrophobic amino acids are able to penetrate cells and reach the cytosol. Here, we have developed a new strategy for developing cyclic cell penetrating peptides (CPPs) that shifts some of the hydrophobic character to the peptide cyclization linker, allowing us to do a linker screen to find cyclic CPPs with improved cellular uptake. We demonstrate that both hydrophobicity and position of the alkylation points on the linker affect uptake of macrocyclic cell penetrating peptides (CPPs). Our best peptide, 4i, is on par with or better than prototypical CPPs Arg9 and CPP12 under assays measuring total cellular uptake and cytosolic delivery. 4i was also able to carry a peptide previously discovered from an in vitro selection, 8.6, and a cytotoxic peptide into the cytosol. A bicyclic variant of 4i showed even better cytosolic entry than 4i, highlighting the plasticity of this class of peptides towards modifications. Since our CPPs are cyclized via their side chains (as opposed to head-to-tail cyclization), they are compatible with powerful technologies for peptide ligand discovery including phage display and mRNA display. Access to diverse libraries with inherent cell permeability will afford the ability to find cell permeable hits to many challenging intracellular targets.

Introduction

Diverse peptide libraries have become indispensable tools for the discovery of ligands and inhibitors to disease targets that are refractory to small molecule drug discovery (1–3). In particular, in vitro selection strategies like phage display or mRNA display can create libraries containing 109 and 1013 unique sequences, respectively (4–7). Additionally, incorporation of unnatural amino acids (8–13) and advances in cyclization strategies (14–16) allow for the generation of mRNA-displayed libraries with enhanced therapeutic relevance due to improved protease stability (17–20). While these approaches reliably uncover stable, high affinity binders to selected intracellular targets, there is no generalizable approach to enable permeability of these peptides (21, 22).

A potential strategy for enabling permeability of these peptides relies on attachment of a linear cell penetrating peptide (CPP), such as Arg9 (23), Tat (24), or Penetratin (25), for cellular uptake (26, 27). While standard CPPs do enable permeability of some cargos, endosomal entrapment remains an issue (28–31). Furthermore, CPPs have been tested in clinical trials, but so far none of these trials have led to an FDA-approved CPP conjugate (27). Recent work by Pei and co-workers has led to the development of short, cyclic CPPs that provide high cellular uptake and endosomal escape (32–35), two ideal characteristics of a generalizable CPP (31, 32). Inclusion of these cyclic CPPs in one-bead-one-compound libraries led to cell permeable peptide inhibitors of protein-protein interactions (PPIs) with nanomolar to low micromolar affinity (36, 37). However, these CPPs are cyclized in a head-to-tail fashion. This type of chemistry is incompatible with co-translational incorporation into peptide libraries using phage display or mRNA display, which require the C-terminus of the peptide to be attached to a phage coat protein or the encoding mRNA respectively (5, 7, 38).

Here we describe the design and optimization of a short CPP compatible with in vitro selections and compare its uptake and cytosolic entry to conventional and cyclic CPPs. This new CPP promises to enable the synthesis of diverse mRNA or phage-displayed peptide libraries with high inherent permeability.

Results and Discussion

Concept for design of new cyclic CPPs

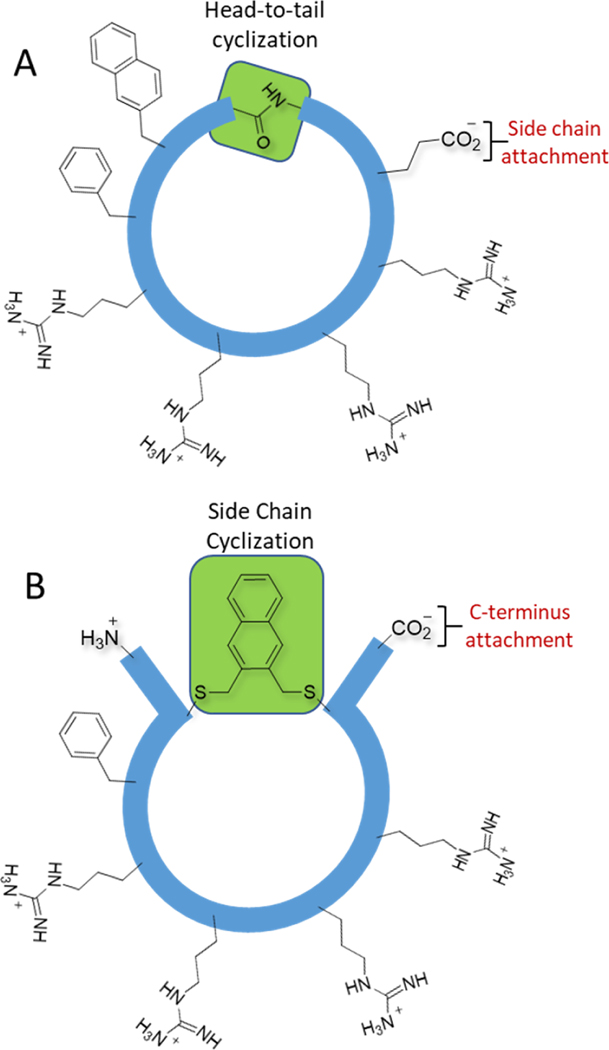

The cyclic CPPs designed by Pei and coworkers include four sequential Arg residues adjacent to two hydrophobic residues (e.g. Phe and 2-naphthylalanine) cyclized in a head-to-tail manner (Figure 1A). Replacing the head-to-tail cyclization approach with a side chain alkylation/cyclization strategy would free up the C-termini for compatibility with the display technologies (Figure 1B). Side chain alkylation also permits a diversity of linkers to be attached in order to optimize cell penetration. Moreover, we anticipated that some of the hydrophobic character could be shifted from the peptide itself to the linker. We chose alkylation chemistry between cysteine and aryl bromomethyl derivatives because of its wide application to peptide library cyclization (16, 19, 39–43).

Figure 1: Cyclic cell penetrating peptides.

(A) A representative of the family of cell penetrating head-to-tail cyclized peptides described by Pei and co-workers. (B) Our strategy, which involves cyclization between cysteine thiols and hydrophobic aryl groups. The 2,3-substituted naphthalene is shown as a representative linker.

Linker screening leads to a peptide with high total cellular uptake.

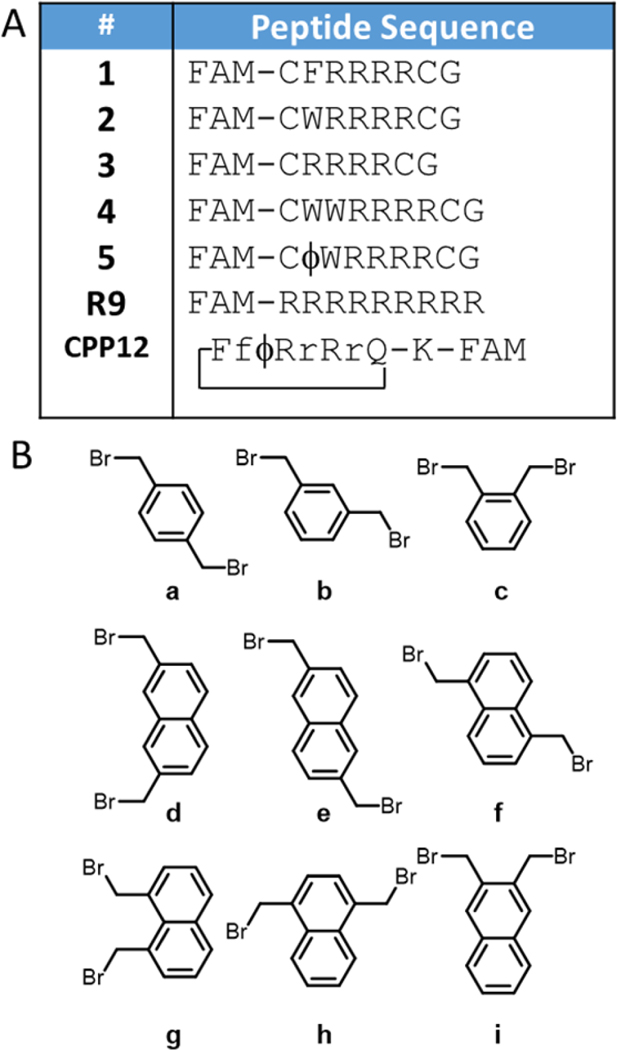

Our initial strategy focused on cyclization of peptides CFRRRRCG (1) and CWRRRRCG (2), chosen because they contained a hydrophobic amino acid adjacent to four arginines, similar to Pei’s head-to-tail cyclized peptides (Figure 2A). We cyclized these peptides with nine different aromatic bromomethyl linkers (a-i) specifically chosen to examine the difference between xylene (a-c) and naphthalene (d-i), as well as the structural diversity provided by the different substitution patterns (Figure 2B), giving peptides 1a through 1i and 2a through 2i. Most of the linkers were commercially available, and the others were synthesized using radical halogenation of the corresponding methyl-substituted naphthalenes (44) (SI, Scheme 1). We purposefully only used symmetrical aromatic linkers to avoid synthesizing mixtures of isomers. Each of the peptides was labeled with carboxyfluorescein (FAM) following a 6-aminohexanoic acid spacer at the N-terminus, and purity was validated by HPLC and MALDI-MS (Figures S1-S8).

Figure 2: Peptides and cyclization linkers.

(A). Potential cell penetrating peptides prepared in this work. Lowercase letters signify D-amino acids. FAM = 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein with an aminohexanoic acid spacer, ϕ = naphthylalanine. CPP12 is cyclized head-to-tail. The K-FAM in CPP12 signifies a lysine attached to the glutamine side chain via the alpha carbon, and 5-FAM attached to lysine via its δ-amino group. (B) Cyclization linkers. In this work cyclic peptides are named by combining the peptide sequence name and the cyclization linker used.

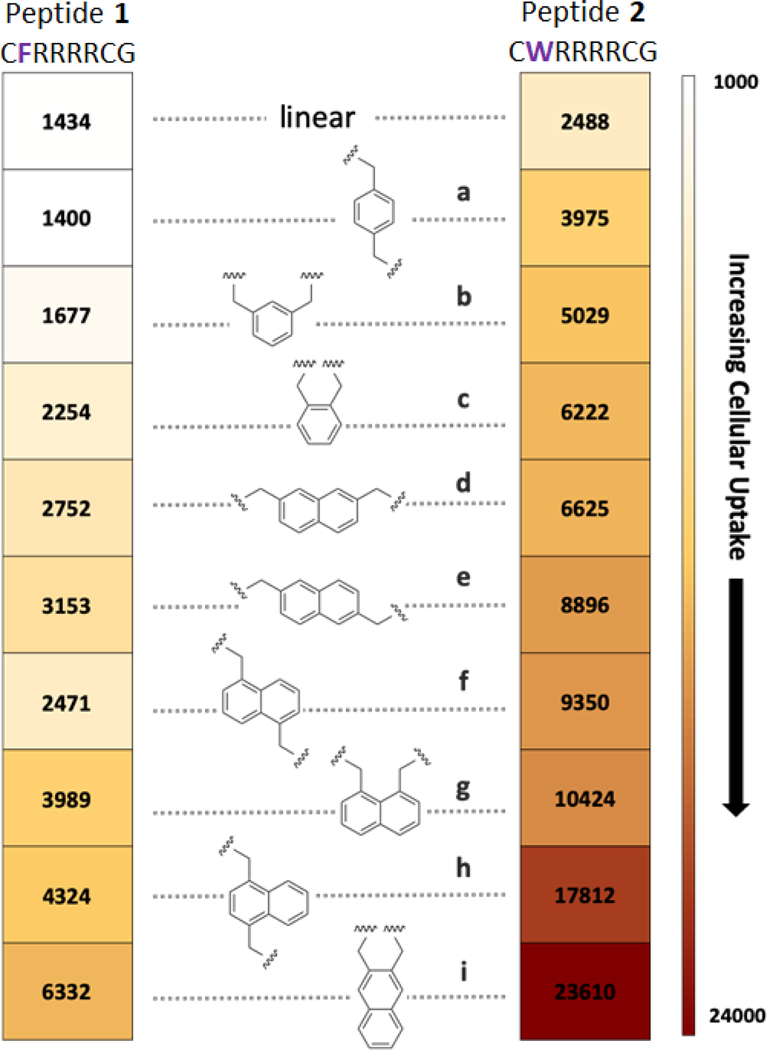

Cellular internalization of each peptide in MDA-MB 231 cells was analyzed via flow cytometry (Figure 3 and Figure S9). Fluorescence due to peptides bound to the cell surface was suppressed by aggressive trypsin treatment and the effectiveness of this process was validated with a cell surface trypan blue quench (45, 46) (Figure S10).

Figure 3: Cellular uptake experiments.

Peptides are arranged from low (top) to high (bottom) permeability in MDA-MB 231 cells as measured by flow cytometry. Each peptide was incubated at a concentration of 5 µM for 2 h. The numbers in the boxes signify the mean fluorescence for cells incubated with that peptide.

Significant differences in cell permeability were observed among the cyclic versions of peptide 1 having various analogs of xylene (1a-1c) and naphthalene (1d-1i) as a linker. Likewise, cyclic peptides designed based on peptide 2 (2a-2i) also displayed varying abilities to penetrate through cell membrane (Figure 3). Several trends were identified. First, the tryptophan-containing peptides (2a-2i) showed better uptake than the phenylalanine-containing peptides (1a-1i). Second, peptides cyclized with naphthalene linkers always resulted in better cellular uptake than the xylene analogues in the context of both peptides. Third, within a given series, there was a correlation between the position of the alkylation points and permeability, with closer attachment points promoting higher permeability. These trends are potentially connected to increases in hydrophobicity as evidenced by HPLC. Although the retention times were quite similar for all compounds, the permeability of the peptides correlated with HPLC retention times (Figure S11). The best CPPs of the group were 2h and 2i, and these were investigated more fully.

Evaluation of the effect of additional hydrophobic amino acids on total cellular uptake.

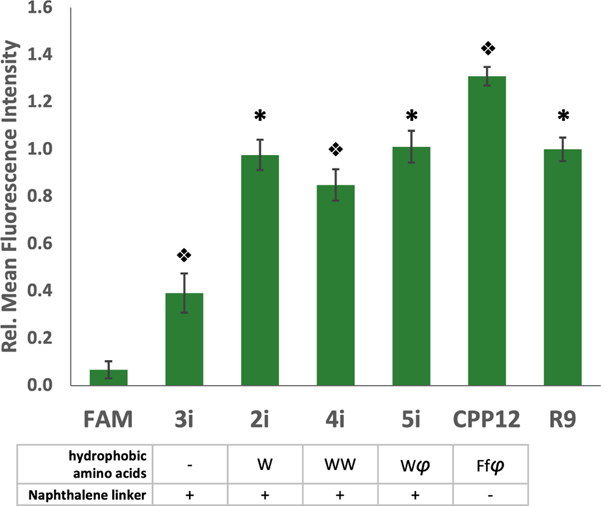

To investigate the effects of increasing numbers of hydrophobic amino acids on cellular uptake, we compared peptides 2–5 (Figure 2A), cyclized with the best linker, i, using flow cytometry (Figure 4 and Figure S12). We also included R9 and Pei’s peptide, CPP12 (33), as positive controls, and the impermeable 5-FAM (47) as a negative control. The peptide with a single Trp (2i) was significantly better than a peptide lacking Trp (3i), showing a similar uptake to R9. Interestingly, addition of either another Trp (4i) or a naphthylalanine (φ, 5i), did not lead to significant improvements. CPP12 demonstrated the highest permeability, but only showed a 1.3-fold enhancement over R9, 2i, and 5i. With the knowledge that our peptides show comparable cellular entry to R9 but are more resistant to proteolysis due to cyclization, and are theoretically compatible with in vitro translation techniques, we further assessed cellular entry of these peptides to ensure true cytosolic delivery.

Figure 4: Hydrophobicity enhances uptake.

Relative fluorescence intensity of peptides with various hydrophobic groups compared to R9 and the reported peptide, CPP12. Each peptide was incubated with MDA-MB 231 cells at a concentration of 5 µM for 2 h. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments. φ = 2-naphthylalanine, f = D-phenylalanine. * indicates significant difference from all other peptides except 2i, 5i, or R9 p<0.001. Split diamonds indicate differences from all other conditions p<0.01, 1-way ANOVA, Tukey.

Standard assays for cytosolic delivery show that our cyclic CPPs are able to enter the cytosol.

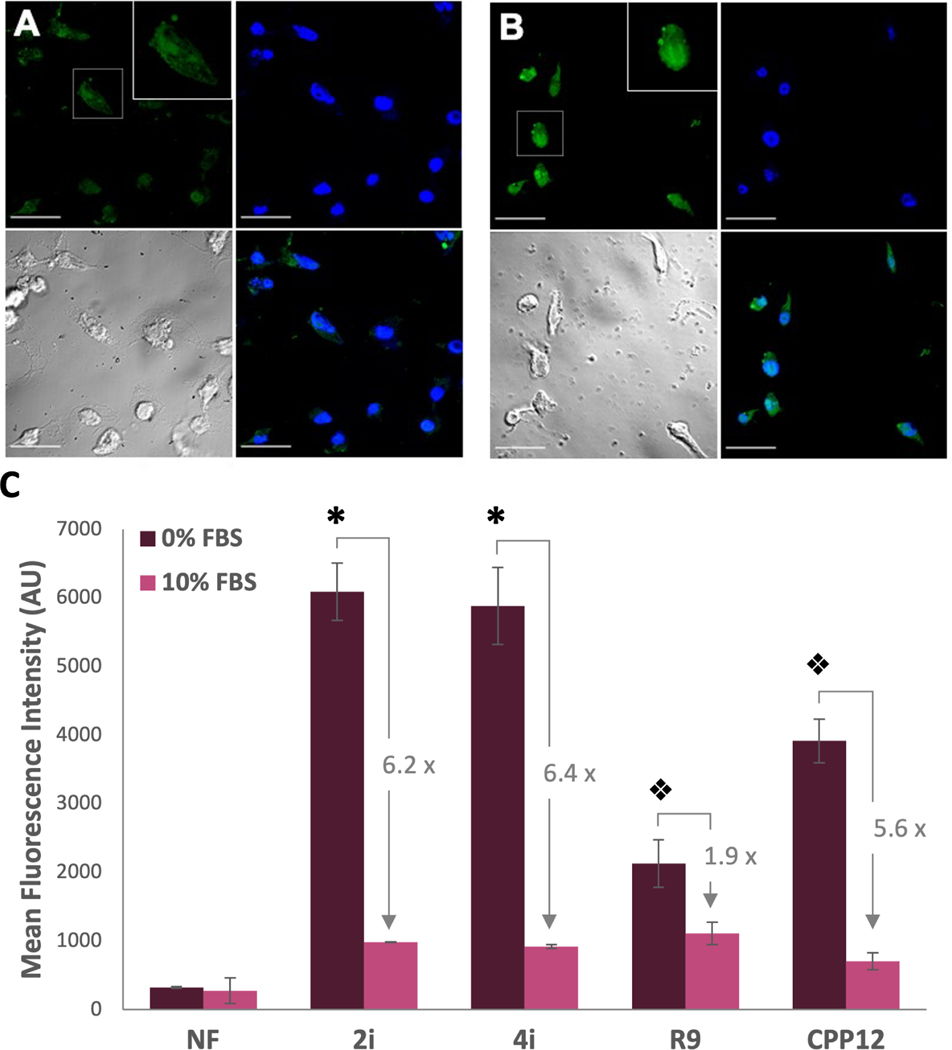

Flow cytometry with fluorescein-labeled peptides measures total cellular uptake, but cannot distinguish if the peptides have successfully escaped the endosomes to reach the cytosol. To measure cytosolic entry, we pursued two reported approaches. First, confocal microscopy of 2i showed time-dependent increases in fluorescence and diffuse fluorescence throughout cells which increased over time, consistent with cytosolic entry after endosomal escape (Figure 5 A,B and Figure S13) (30, 31). We then prepared carboxynaphthofluorescein (NF) versions of our peptides to monitor cytosolic entry. This fluorophore is useful for measuring cytosolic entry because the pKa of the naphthofluorescein renders it minimally fluorescent at endosomal/lysosomal pH but highly fluorescent in the cytosol (48). We compared cytosolic entry of 2iNF,4iNF, CPP12NF, and R9NF in the presence and absence of 10% FBS using naphthofluorescein as a negative control. Within serum-free conditions, 2iNFand 4iNF showed statistically identical cytosolic entry that was significantly higher than all other peptides (Figure 5C). Cytosolic entry of each of the peptides was significantly affected by the presence of serum, which corelates to previous studies with CPP12 (49). 2iNF and 4iNF demonstrated similar reductions in fluorescence (6.2-fold and 6.4-fold, respectively), while CPP12NF showed a 5.6-fold reduction. R9NF was least affected, only reducing by 1.9-fold. The cytosolic entry in the presence of serum was similar for all of the peptides (Figure 5C and Figure S14).

Figure 5: Evidence for cytosolic entry of CPPs.

(A) and (B): Confocal micrographs for live-imaged MDA-MB 231 cells treated for 2 h (A) and 4 h (B) with 5 µM of 2i. Upper left—green channel showing the peptide, Upper right—blue channel showing the DAPI nuclear stain, Lower left—brightfield image, and Lower right—merge. Scale bar = 30 µm (C) Flow cytometry of carboyxnaphthofluorescein-labeled peptides. MDA-MB 231 cells were treated with 5 µM peptide for 2 h in DMEM without (0%, dark purple bars) or with (10%, pink bars) FBS. Fold changes for each peptide between serum-free and serum-supplemented media are shown. * indicates a significant difference from peptides other than 2iNF or 4iNF within a group (p<0.001). Split diamonds indicate significant differences between all other peptides within a group (p<0.001). NF is shown as an arithmetic mean as some cells exhibited negative fluorescence, preventing calculation of a geometric mean.

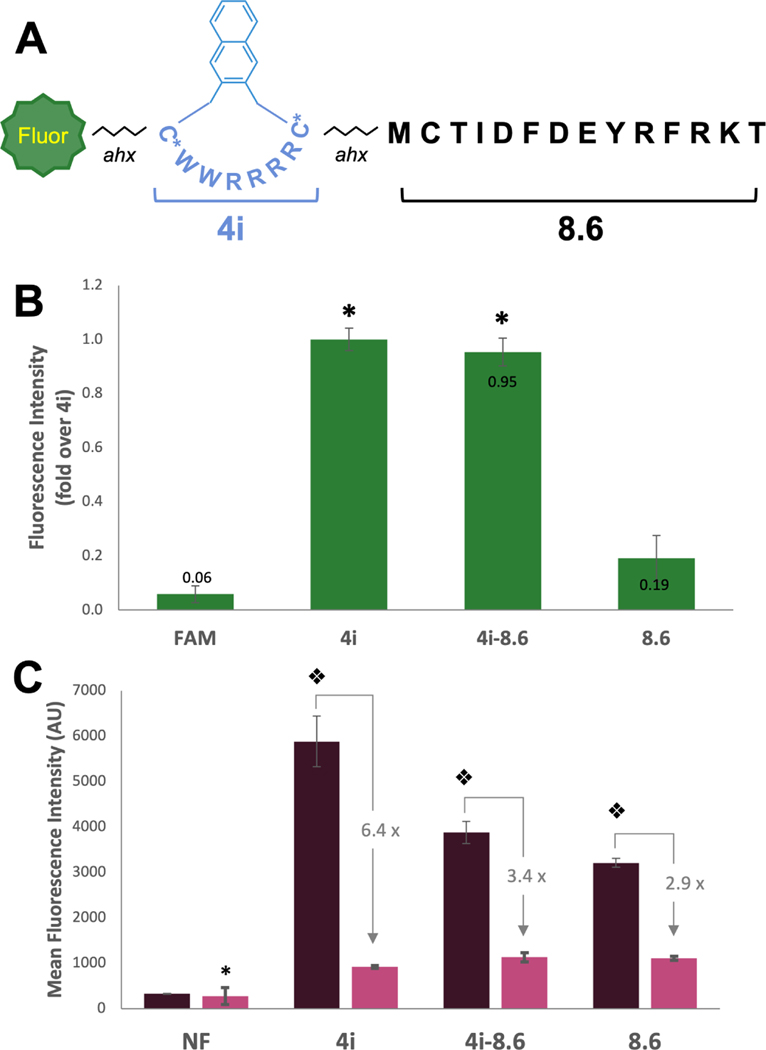

Peptide 4i is able to deliver impermeable cargo into the cytosol.

We next attached 4i to a cell impermeable cargo found during an in vitro selection: peptide 8.6 (Figure 6A), a known inhibitor of protein-protein interactions involving the tandem BRCT domains of breast cancer associated protein 1 (BRCA1) (50). To create our conjugate, we simply appended the sequence of peptide 4 onto the N-terminus of 8.6 using standard peptide coupling chemistry. This peptide was cyclized on resin with linker i regioselectively using orthogonal cysteine protecting groups (Cys-StBu in the CPP portion).

Figure 6: Peptide 4i enables delivery of cell-impermeable peptide cargo.

(A) Structure of peptide 4i-8.6. (B) Relative fluorescence intensity of FAM-labeled peptides measured by flow cytometry as compared to 4i. MDA-MB 231 cells were incubated with 5 µM FAM-labeled peptide for 2 h, trypsinized, and total cellular uptake was measured by flow cytometry (488 nm laser, 530/30A filter). Bars represent the relative geometric mean fluorescence intensity across 3 replicates. Fold change over 4i is labeled on bars. * indicates significant difference from FAM and 8.6. (C) Mean (geometric) fluorescence intensity of NF-labeled peptides measurd by flow cytometry. MDA-MB 231 cells were incubated with 5 µM NF-labeled peptides in serum-free or 10% serum media for 2 h, trypsinized, and total cellular uptake was measured flow cytometry (633 nm laser. 660/20A filter). * indicates difference from peptides in the 10% serum condition (p<0.025). Split diamond indicates significant difference from all conditions (2-way ANOVA, Holm-Sidak, p<0.003). NF is shown as an arithmetic mean as some cells exhibited negative fluorescence, preventing calculation of a geometric mean.

The cellular uptake of the resulting peptide, 4i-8.6 was compared with 8.6. As expected, 4i-8.6 showed significantly higher uptake than 8.6 via standard flow cytometry (Figure 6 B, S15), reaching similar cellular uptake to 4i. To assess cytosolic delivery, we then prepared naphthofluorescein-labeling experiments, testing 4i-8.6NF in both serum-free and high serum conditions relative to 8.6NF and 4iNF (Figure 6 C, S14). In the absence of serum, 4iNF showed enhanced cytosolic entry relative to 4i-8.6NF (p<0.001) and maintained higher entry into cells than 8.6NF (p=0.02) . We also tested R9–8.6NF but found that it was toxic to cells at 5 µM and therefore it was not included in our analysis. In the presence of 10% serum, 4iNF, 4i-8.6NF, and surprisingly 8.6NF all demonstrated similar levels of cellular entry. Given that 8.6 is relatively impermeable when labeled with FAM, we surmise that the increased hydrophobicity of the NF fluorophore improved cellular entry. Taken together, these studies show 4i is able to carry peptide cargos into cells, similar to other CPPs.

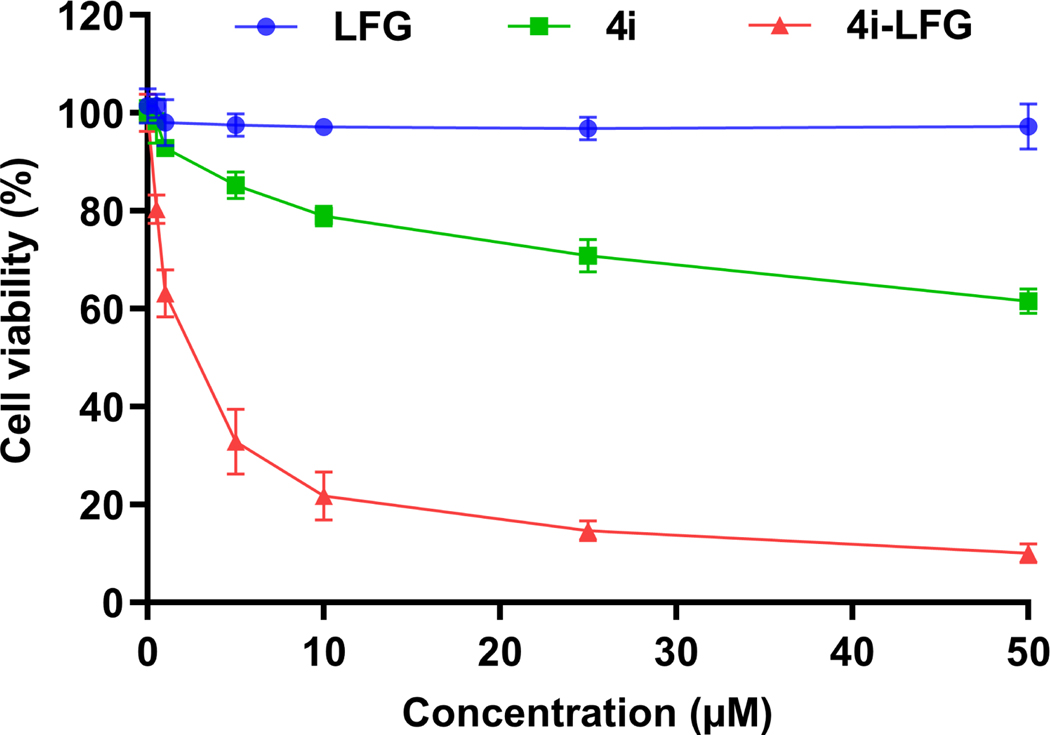

Peptide 4i delivers a cytotoxic peptide into the cytosol.

To further give evidence for cytosolic delivery, we conjugated 4i to the cancer cell-selective cytotoxic peptide, PVKRRLFG (LFG). LFG is known to block the interaction of the cyclin A/cdk2 complex with substrates (51, 52) and this leads to cancer-cell selective toxicity through blocking of E2F phosphorylation (52, 53). The cyclin A/cdk2 complex is known to shuttle between the cytosol and nucleus (54). Conjugates of LFG with conventional CPPs (Tat, Pen) are known to have micromolar IC50 values in various cancer cell lines, and have shown moderate efficacy in multiple cancer mouse models (53). We treated U2OS osteosarcoma cells with LFG, non-labeled 4i, and non-labeled 4i-LFG (Figure 7). As expected (52), LFG alone was non-toxic to the cells even at the highest concentration tested (50 μM). 4i-LFG, on the other hand, had an IC50 of 2.1 μM, evidence that CPP 4i was able to deliver the LFG peptide into the cytosol. 4i itself did show weak cytotoxicity, with an IC50 > 50 μM.

Figure 7: Cytotoxicity assay of peptides LFG, 4i, and 4i-LFG against U2OS cells.

Cell viability was measured after 24 h incubation using CellTiter-Glo reagent. The results represent the data obtained from the experiments performed in triplicate. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

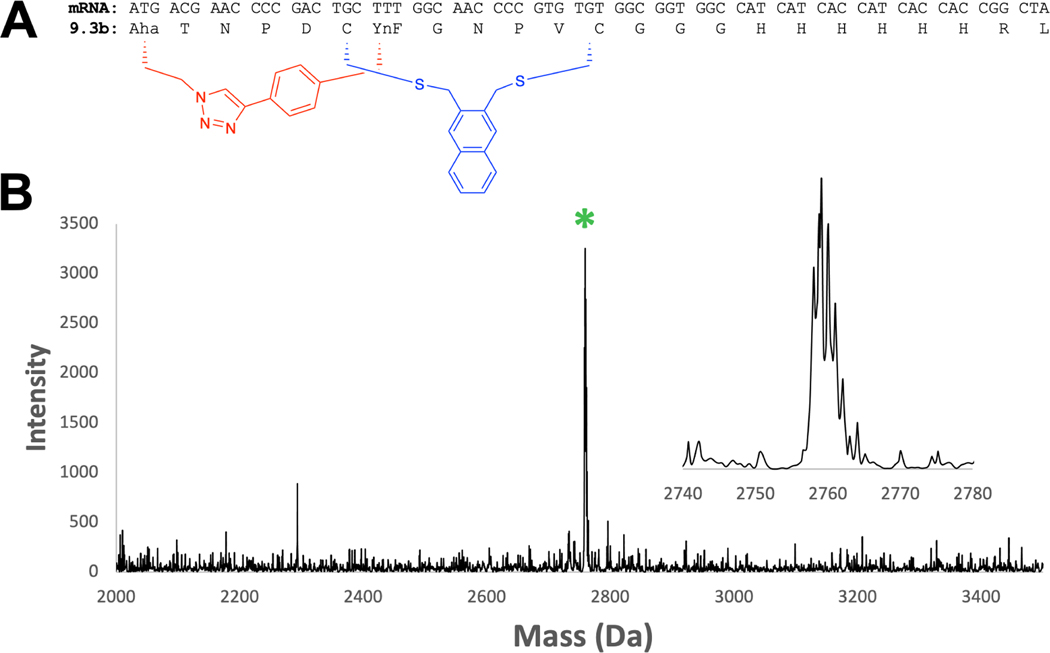

Peptide 4i is compatible with in vitro translation

Looking forward, a CPP such as 4i would be desirable to append during the process of selection, thus tying both cell permeability and target affinity to any peptides as they emerge from selection. Previous work from our lab has demonstrated the compatibility of mRNA display with two orthogonal cyclization chemistries, cysteine bis-alkylation using m-dibromoxylene (DBX) (Figure 2 B compound b) and copper mediated azide-alkyne cyclizaiton (CuAAC) (18, 19). The change from DBX to 2,3-bis(bromomethyl)naphthalene is a potentially significant one, as the naphthalene is likely to be less soluble in the aqueous milieu required for in vitro selections. To test this, we took a mRNA previously identified from an in vitro selection (18) and performed an in vitro translation reaction in the presence of the methionine surrogate γ-azidohomoalaine (Aha) and phenylalanine analog p-ethynylphenylalanine (YnF) (Figure 8 A). We then captured this peptide on Ni-NTA and performed sequential cysteine alkylation with 2,3-bis(bromomethyl)naphthalene and CuAAC. The reactions were monitored by MALDI-MS. Since the click reaction does not lead to a mass change, we added 5 mM of the phosphine TCEP to reduce any remaining azide to the amine using Staudinger chemistry. As seen in Figure 8 B, only the bicyclic peptide mass is observed, indicating a complete bicyclization of the peptide. The only change in the protocol involved increasing the acetonitrile concentration to 50% during cysteine alkylation to improve solubility of the 2,3-bis(bromomethyl)naphthalene linker and allowing for greater reaction time, with 2 hours at room temperature resulting in complete cyclization. With this small change, the 2,3-bis(bromomethyl)naphthalene chemistry can be incorporated into mRNA display or phage display selection protocols.

Figure 8: Linker i is compatible with in vitro translation.

(A) mRNA coding sequence for peptide 9.3b, discovered in Hacker et. al. (18). The blue macrocycle is formed via cysteine bisalkylation using 2,3-bis(bromomethyl)naphthalene. The red macrocycle is formed via copper-assisted click between L-β-azidohomoalanine (Aha) and p-ethynyl-L-phenylalanine (YnF). (B) In vitro translation of peptide 9.3b followed by bicyclization on Ni-NTA resin yields a single major product of bicyclized peptide. Expected m/z : 2759.18 [M+H]+ . Observed: 2759.12.

Bicyclization of 4i improves cytosolic entry.

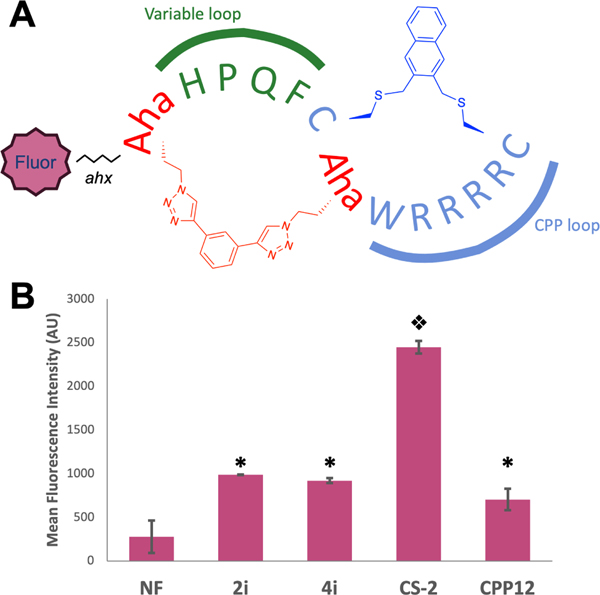

To further investigate the consequences of bicyclization on the cell permeability of 4i and to simulate a peptide that could be identified using mRNA display, we prepared a naphthofluorescein-labeled bicyclic peptide CS-2NF and directly tested its ability to enter the cytosol (Figure 9 A). This peptide traded one of the tryptophan residues in 4i for an azidohomoalanine (Aha), providing a cyclization handle for click chemistry with a second Aha residue at the N-terminus using Spring’s double click approach (55). We reasoned that the hydrophobic triazole formed after click would be sufficient to maintain permeability. To our delight, this peptide showed over 2.5-fold enhanced cytosolic entry relative to 2i, 4i, and CPP12, in the presence of 10% serum (Figure 9 B, S16, p<0.001). Although it would be presumptuous to conclude that this enhanced permeability would extend to bicycles of any size and composition, it is highly encouraging that addition of a second, overlapping ring not only does not destroy the activity of 4i, but rather improves it.

Figure 9: Selection-compatible bicyclization improves cytosolic entry.

(A) Structure of peptide CS-2NF. The peptide contains two rings, one available for variable sequences (green) closed by a bis-alkyne linker, and another (blue) containing the CPP sequence. Fluorophores for study are appended to the N-terminal azidohomoalanine via an aminohexanoic acid spacer. (B) Mean fluorescence intensity of NF-labeled peptides in media containing 10% serum. MDA-MB 231 cells were incubated in 5 μM NF-labeled peptide for 2 h, trypsinized, and analyzed via flow cytometry (633 nm laser, 660/20A filter). * indicates significant difference from both NF and CS-2NF . Split diamonds indicate significant difference from all conditions (1-way ANOVA, Tukey, p<0.001). NF is shown as an arithmetic mean as some cells exhibited negative fluorescence, preventing calculation of a geometric mean.

Summary and Outlook

The main focus of our work was the development of a new cyclic CPP, 4i, that provides high cellular uptake and endosomal escape. This new CPP is expected to have several important benefits. First, we have shown that the alkylating group contributes significantly to permeability (Figure 3) enabling simple linker screening for future optimizations (41, 56). Second, unlike CPPs cyclized in a head-to-tail fashion, peptide 4i is easily implemented into an in vitro translation workflow (Figure 8). This opens the door for the use of in vitro selection strategies to optimize the peptide sequence for enhanced permeability (57–59). Moreover, we have attached 4i onto a peptide discovered using mRNA display, and have shown that while cytosolic entry is diminished, the conjugate is on par with prototypical CPPs. Peptide 4i is also able to deliver a cell impermeable cytotoxic peptide into the cytosol. Finally, we have demonstrated that bicyclization can enhance cytosolic entry through the synthesis of a peptide similar to those created in some mRNA-displayed peptide libraries. Taken together, the novel CPPs described herein open the doors for the creation of diverse bicyclic peptide libraries containing peptides with inherent cell permeability and promise to provide a new source of leads in drug discovery for difficult targets.

Materials and Methods

Peptide synthesis.

The peptides were synthesized using a Liberty Automated Peptide Synthesizer with a Discover Microwave module (CEM). Rink Amide MBHA resin (EMD Millipore, CEM) was chosen as the solid support for a standard 0.1 mmol scale synthesis using standard N-α-Fmoc-protected amino acids (CEM, Chem Impex). Cys-StBu was coupled using the 50 °C coupling temperature (standard Cys coupling method). Azidohomoalanine was coupled for one hour at room temperature. Peptides were synthesized using HATU/DIEA or DIC/Oxyma, with 10 eq. of amino acid added at each coupling. All reagents were freshly prepared the day of each synthesis.

Pe ptide cyclization.

S-tBu protected cysteines were orthogonally deprotected by treatment with 50 mM dithiothreitol, 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate in DMF at 37 °C for 3 h (50 mg resin per 1 mL of S-tBu deprotection solution). The deprotection was repeated, if necessary, until complete removal of the S-tBu protecting group was observed by mass spectrometry. Cyclization was achieved with 170 μM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, 17 mM ammonium carbonate, and 8 mM dibromo linker in DMF at 37 °C for 2 h (50 mg resin per 2.5 mL of cyclization solution). For on-resin cysteine deprotection and cyclization, the resin was loaded into Poly-Prep Chromatography Columns (BioRad) and capped for each reaction. The columns were slowly rotated using a rotisserie for each reaction. The reagents were subsequently removed via vacuum filtration through the filter at the bottom of each column. The resin was then washed thoroughly with alternating methanol and dichloromethane and dried by pulling a stream of air for at least 10 min to remove the volatile solvent prior to storage.

Peptide N-terminus fluorescent labeling.

The 5(6)-carboxyfluroescein was synthesized as described (60). The NHS coupling to the 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein was achieved as described (61). In order to measure cellular uptake by fluorescence, 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein was coupled to the N-terminus of peptides (62) containing 6-aminohexanoic acid as a spacer between the peptide and fluorescent tag. An N-hydroxysuccinimide-activated carboxyfluorescein (NHS-FAM) was synthesized and used to provide faster reaction times and lower equivalents needed (0.05 mmol of peptidyl resin was incubated with 75 mg of NHS-FAM (0.158 mmol) in 5 mL DMF, 45 μL DIPEA for 3 h). Carboxynaphthofluorescein-labeled peptides were synthesized as described (48). The solution was drained and the resin was washed with DMF, DCM, and MeOH. The reaction was monitored by cleaving small amounts of resin and analyzing by mass spectrometry, in case an additional coupling was needed before cleavage from the resin.

Bicyclization of CS-2.

The one-pot bicyclization of CS-2 was achieved via cysteine cyclization and azide-alkyne click chemistry adapted from Richelle et al (63). All solutions were puged with Ar prior to use. Labeled, cleaved peptide was dried and dissolved in 1:1 water:DMF to a final concentration of 5 mM. Cysteine cyclization was achieved by first adding 1.1 eq of 2,3 bis(bromomethyl)naphthalene in DMF followed by aq. sodium bicarbonate to raise the pH>8. The reaction was allowed to proceed at room temperature for 20 min and checked via MALDI. After successful cysteine cyclization was confirmed, 1.1 eq of 1,3 diethynylbenzene in DMF was added to the peptide solution. Separately, 2 eq of CuSO4 were dissolved in water and added to 2 eq of THPTA in water, forming a dark blue solution. 10 eq of sodium ascorbate were added, turning the solution brown then clear. This mixture was added to the peptide solution, which was then purged with argon. Cyclization occurred at room temperature for 25 min and was monitored via HPLC. Once complete, the peptide was purified via HPLC.

Mammalian cell culture.

MDA-MB 231 cells were maintained in DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium) supplemented with 10% FBS at 37 °C, with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity, until needed. They were grown in T-75 or T-150 flasks (Greiner) and passaged every 2–3 days.

Flow Cytometry.

MDA-MB 231 cells were seeded the day prior at 75,000 cells/well in a 24-well plate with 1 mL DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Three wells were prepared for each peptide as well as for positive and negative controls. The cells were removed from the incubator and a glass pipette connected to a vacuum line was used to remove the media from each well. Cells were incubated with 250 μL of media containing 5 μM fluorescently-labeled peptide for 2 h. After the 2 h incubation, the media was removed and cells were gently washed three times with 500 μL of 1x PBS. Cells were treated with 250 μL trypsin (0.05% or 0.25%) for 5 min at 37 °C to lift from the plate and digest any extracellular bound peptide. The trypsin-cell solution was then transferred to individual centrifuge tubes for a 5 min centrifugation at 1800 rpm to pellet the cells. The supernatant was carefully removed. Cells were rinsed again with 300 uL of cold PBS, spun, and resuspended with 300 μL of cold 1x PBS and stored on ice until injection into the BD FACSCanto II Analyzer. Healthy cells were gated based on their forward and side scatter properties in order to remove any dead cells or debris from analysis.

Each peptide sample was analyzed until 10,000 counts of healthy, single cells were obtained. Experiments with fluorescein-labeled peptides used a 488 nm laser and either 530/30 or 585/42 bandpass filters. Experiments with naphthofluorescein-labeled peptides used a 633 nm laser and a 660/20 bandpass filter. Mean fluorescent values correspond to the geometric mean unless otherwise stated.

For Trypan Blue quenching of extracellular bound peptides, the cells followed the same procedure as above but were treated with a 0.05% trypan blue solution prior to injection into the BD FACSCanto II Analyzer (45) .

Confocal microscopy.

MDA-MB 231 cells were cultured at 37 °C in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. The cells were plated on top of coverslips at 1.0 × 105 cells per well in a 12-well plate overnight. The following morning, the media was removed and each well of cells was incubated with 500 μL of 5 μM peptide in media at 37 °C for 2 h or 4 h. The media was carefully removed and cells washed with 1x PBS. Cells were incubated with DAPI (4’6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) in 1x PBS solution (1 mL of 250 nM for 5 min). The DAPI solution was removed and cells were washed twice with 2 mL of 1x PBS. Slides were treated with ProLong Gold Antifade (Invitrogen) to prevent photobleaching. A Zeiss LSM 710 on the Inverted Axio Observer Microscope was used at 63x magnification. Excitation/Emission: FAM- 488/531 nm, DAPI- 405/447 nm.

Cytotoxicity assays.

In vitro cytotoxicity of peptides LFG, 4i, and 4i-LFG against U2OS cells was determined by conducting CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega, Madison, WI). U2OS cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 3 × 103 cells/well. The cells were treated with peptides in triplicate at a concentration level of 0.5–50 μM and incubated for 24h at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. After the incubation period, CellTiter-Glo reagent (25 μL) was added to each well and the plate was incubated for 30 minutes in the dark at room temperature. Cell viability was determined by measuring the luminescence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The bulk of this work was supported by the NIH (R01CA166264) and the Massey Cancer Center. K. Mitra was supported by the Virginia Commonwealth Health Research Board (236-03-16). The NSF supported C. Simek and the chemistry development for the synthesis of CS-2 (1904872). The Gilbert Family Foudation (521006) supported Sandeep Lohan and the toxicity study. Services and products in support of the research project were generated by the VCU Massey Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Shared Resource, the Microscopy Shared Resource, and the Proteomics research with funding from the NIH-NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA016059. We thank D. Prosser (Dept of Biology, Virginia Commonwealth University) for helpful suggestions with the uptake data, and A. Kazi (Virginia Commonwealth University) for help on the cytotoxicity experimental design.

N. Abrigo and M. Hartman have applied for a provisional patent on the technology described in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary Info

Supplementary info including: supplementary methods, synthesis of bromomthyl naphthalenes (Scheme S1), Characterization of the peptides (Figures S1-S8), FACS histogram plots (Figures 9,12, 14-16), Trypan blue quench experiments (Figure S10), Correlation of HPLC retention time with uptake (Figure S11), confocal imaging of uptake (Figure S13), MALDI masses (Table S1) and NMR spectra of bisbromomethyl naphthalenes is available online. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Foster AD, Ingram JD, Leitch EK, Lennard KR, Osher EL, and Tavassoli A. (2015) Methods for the Creation of Cyclic Peptide Libraries for Use in Lead Discovery.J. Biomol. Screen. 20, 563–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang Y, Wiedmann MM, and Suga H. (2019) RNA Display Methods for the Discovery of Bioactive Macrocycles. Chem. Rev. 119, 10360–10391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Josephson K, Ricardo A, and Szostak JW. (2014) mRNA display: from basic principles to macrocycle drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today 19, 388–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galán A, Comor L, Horvatić A, Kuleš J, Guillemin N, Mrljak V, and Bhide M. (2016) Library-based display technologies: where do we stand? Mol. Biosyst. 12, 2342–2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith GP, and Scott JK. (1993) Libraries of Peptides and Proteins Displayed on Filamentous Phage. Meth. Enzymol. 333–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis AM, Plowright AT, and Valeur E. (2017) Directing evolution: the next revolution in drug discovery? Nat. Rev. Drug Disc. 16, 681–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts RW, and Szostak JW. (1997) RNA-peptide fusions for the in vitro selection of peptides and proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 94, 12297–12302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iqbal ES, Dods KK, and Hartman MCT. (2018) Ribosomal incorporation of backbone modified amino acids via an editing-deficient aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. Org. Biomol. Chem. 16, 1073–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murakami H, Ohta A, Ashigai H, and Suga H. (2006) A highly flexible tRNA acylation method for non-natural polypeptide synthesis. Nat. Methods 3, 357–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Josephson K, Hartman MCT, and Szostak JW. (2005) Ribosomal Synthesis of Unnatural Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 11727–11735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartman MCT, Josephson K, and Szostak JW. (2006) Enzymatic aminoacylation of tRNA with unnatural amino acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 103, 4356–4361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li S, Millward S, and Roberts R. (2002) In vitro selection of mRNA display libraries containing an unnatural amino acid. Journal of the American Chemical Society 124, 9972–9973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frankel A, Millward SW, and Roberts RW. (2003) Encodamers: unnatural peptide oligomers encoded in RNA. Chem. Biol. 10, 1043–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goto Y, Ohta A, Sako Y, Yamagishi Y, Murakami H, and Suga H. (2008) Reprogramming the Translation Initiation for the Synthesis of Physiologically Stable Cyclic Peptides. ACS Chem. Biol. 3, 120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Millward SW, Takahashi TT, and Roberts RW. (2005) A General Route for Post-Translational Cyclization of mRNA Display Libraries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 14142–14143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schlippe YVG, Hartman MCT, Josephson K, and Szostak JW. (2012) In Vitro Selection of Highly Modified Cyclic Peptides That Act as Tight Binding Inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 10469–10477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fiacco SV, Kelderhouse LE, Hardy A, Peleg Y, Hu B, Ornelas A, Yang P, Gammon ST, Howell SM, Wang P, Takahashi TT, Millward SW, and Roberts RW. (2016) Directed Evolution of Scanning Unnatural-Protease-Resistant (SUPR) Peptides for in Vivo Applications. ChemBioChem 17, 1643–1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hacker DE, Hoinka J, Iqbal ES, Przytycka TM, and Hartman MCT. (2017) Highly Constrained Bicyclic Scaffolds for the Discovery of Protease-Stable Peptides via mRNA Display. ACS Chem. Biol. 12, 795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hacker DE, Abrigo NA, Hoinka J, Richardson SL, Przytycka TM, and Hartman MCT. (2020) Direct, Competitive Comparison of Linear, Monocyclic, and Bicyclic Libraries Using mRNA Display. ACS Comb. Sci. 22, 306–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawamura A et al. (2017) Highly selective inhibition of histone demethylases by de novo macrocyclic peptides. Nat. Commun. 8, 14773–14773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walport LJ, Obexer R, and Suga H. (2017) Strategies for transitioning macrocyclic peptides to cell-permeable drug leads. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 48, 242–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naylor MR, Bockus AT, Blanco M-J, and Lokey RS. (2017) Cyclic peptide natural products chart the frontier of oral bioavailability in the pursuit of undruggable targets. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 38, 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell DJ, Steinman L, Kim DT, Fathman CG, and Rothbard JB. (2000) Polyarginine enters cells more efficiently than other polycationic homopolymers. J. Pept. Res. 56, 318–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mann DA, and Frankel AD. (1991) Endocytosis and targeting of exogenous HIV-1 Tat protein. EMBO J. 10, 1733–1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Derossi D, Joliot AH, Chassaing G, and Prochiantz A. (1994) The third helix of the Antennapedia homeodomain translocates through biological membranes. J Biol. Chem. 269, 10444–10450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guidotti G, Brambilla L, and Rossi D. (2017) Cell-penetrating peptides: from basic research to clinics. Trends in pharmacological sciences 38, 406–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Habault J, and Poyet J-L. (2019) Recent Advances in Cell Penetrating Peptide-Based Anticancer Therapies. Molecules 24, 927–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allen J, Brock D, Kondow-McConaghy H, and Pellois J-P. (2018) Efficient Delivery of Macromolecules into Human Cells by Improving the Endosomal Escape Activity of Cell-Penetrating Peptides: Lessons Learned from dfTAT and its Analogs. Biomolecules 8, 50–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stewart MP, Lorenz A, Dahlman J, and Sahay G. (2016) Challenges in carrier-mediated intracellular delivery: moving beyond endosomal barriers. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 8, 465–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pei D. (2018) Overcoming Endosomal Entrapment in Drug Delivery with Cyclic Cell-Penetrating Peptides. Bioconjug. Chem. 30, 273–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deprey K, Becker L, Kritzer J, and Plückthun A. (2019) Trapped! A critical evaluation of methods for measuring total cellular uptake versus cytosolic localization. Bioconj. Chem. 30, 1006–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dougherty PG, Sahni A, and Pei D. (2019) Understanding Cell Penetration of Cyclic Peptides. Chem. Rev. 119, 10241–10287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qian Z, Martyna A, Hard RL, Wang J, Appiah-Kubi G, Coss C, Phelps MA, Rossman JS, and Pei D. (2016) Discovery and Mechanism of Highly Efficient Cyclic Cell-Penetrating Peptides. Biochemistry 55, 2601–2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qian Z, Larochelle JR, Jiang B, Lian W, Hard RL, Selner NG, Leuchapanichkul R, Barrios AM, and Pei D. (2014) Early endosomal escape of a cyclic cell-penetrating peptide allows effective cytosolic cargo delivery. Biochemistry 53, 4034–4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qian Z, Liu T, Liu YY, Briesewitz R, Barrios AM, Jhiang SM, and Pei D. (2013) Efficient delivery of cyclic peptides into mammalian cells with short sequence motifs. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 423–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang B, and Pei D. (2015) A Selective Cell-Permeable Nonphosphorylated Bicyclic Peptidyl Inhibitor against Peptidyl-Prolyl Isomerase Pin1. J. Med. Chem. 58, 6306–6312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rhodes CA, Dougherty PG, Cooper JK, Qian Z, Lindert S, Wang Q-E, and Pei D. (2018) Cell-Permeable Bicyclic Peptidyl Inhibitors against NEMO-IκB Kinase Interaction Directly from a Combinatorial Library. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 12102–12110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurz M, Gu K, and Lohse PA. (2000) Psoralen photo-crosslinked mRNA-puromycin conjugates: a novel template for the rapid and facile preparation of mRNA-protein fusions. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, E83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hacker DE, Almohaini M, Anbazhagan A, Ma Z, and Hartman MCT. (2015) Peptide and peptide library cyclization via bromomethylbenzene derivatives. Methods Mol. Biol. 1248, 105–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Timmerman P, Beld J, Puijk WC, and Meloen RH. (2005) Rapid and Quantitative Cyclization of Multiple Peptide Loops onto Synthetic Scaffolds for Structural Mimicry of Protein Surfaces. ChemBioChem 6, 821–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fairlie DP, and de Araujo AD. (2016) Stapling peptides using cysteine crosslinking.Biopolymers 106, 843–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wallbrecher R, Depré L, Verdurmen WPR, Bovée-Geurts PH, van Duinkerken RH, Zekveld MJ, Timmerman P, and Brock R. (2014) Exploration of the Design Principles of a Cell-Penetrating Bicylic Peptide Scaffold. Bioconj. Chem. 25, 955–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iqbal ES, Richardson SL, Abrigo N, Dods K, Fanco HEO, Gerrish HS, Kotapati HK, Morgan IM, Masterson DS, and Hartman MCT. (2019) A new strategy for the in vitro selection of stapled peptide inhibitors by mRNA display. Chem. Commun. 55, 8959–8962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Higashi T, Uemura K, Inami K, and Mochizuki M. (2009) Unique behavior of 2, 6-bis (bromomethyl) naphthalene as a highly active organic DNA crosslinking molecule. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 17, 3568–3571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Traboulsi H, Larkin H, Bonin M-A, Volkov L, Lavoie CL, and Marsault Éric, (2015) Macrocyclic Cell Penetrating Peptides: A Study of Structure-Penetration Properties. Bioconj. Chem. 26, 405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang D, Yu M, Liu N, Lian C, Hou Z, Wang R, Zhao R, Li W, Jiang Y, and Shi X. (2019) A sulfonium tethered peptide ligand rapidly and selectively modifies protein cysteine in vicinity. Chemical science 10, 4966–4972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu P, Liu B, and Kodadek T. (2005) A high-throughput assay for assessing the cell permeability of combinatorial libraries. Nat. Biotechnol. 23, 746–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qian Z, Dougherty PG, and Pei D. (2015) Monitoring the cytosolic entry of cell-penetrating peptides using a pH-sensitive fluorophore. Chem. Commun. 51, 2162–2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song J, Qian Z, Sahni A, Chen K, and Pei D. (2019) Cyclic Cell-Penetrating Peptides with Single Hydrophobic Groups. ChemBioChem 20, 2085–2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.White ER, Sun L, and Ma Z. (2015) Peptide Library Approach to Uncover Phosphomimetic Inhibitors of the BRCA1 C-Terminal Domain. ACS Chem. Biol. 10, 1198–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adams PD, Sellers WR, Sharma SK, Wu AD, Nalin CM, and Jr WGK. (1996) Identification of a cyclin-cdk2 recognition motif present in substrates and p21-like cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. Molecular and cellular biology 16, 6623–6633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen Y-NP, Sharma SK, Ramsey TM, Jiang L, Martin MS, Baker K, Adams PD, Bair KW, and Jr WGK. (1999) Selective killing of transformed cells by cyclin/cyclin-dependent kinase 2 antagonists. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 96, 4325–4329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mendoza N, Fong S, Marsters J, Koeppen H, Schwall R, and Wickramasinghe D. (2003) Selective cyclin-dependent kinase 2/cyclin A antagonists that differ from ATP site inhibitors block tumor growth. Cancer research 63, 1020–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jackman M, Kubota Y, Elzen ND, Hagting A, and Pines J. (2002) Cyclin A-and cyclin E-Cdk complexes shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Molecular biology of the cell 13, 1030–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lau YH, Wu Y, Andrade PD, Galloway WR, and Spring DR. (2015) A two-component’double-click’approach to peptide stapling. Nature Protocols 10, 585–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jo H, Meinhardt N, Wu Y, Kulkarni S, Hu X, Low KE, Davies PL, DeGrado WF, and Greenbaum DC. (2012) Development of α-helical calpain probes by mimicking a natural protein-protein interaction. Journal of the American Chemical Society 134, 17704–17713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee J-H, Song HS, Lee S-G, Park TH, and Kim B-G. (2012) Screening of cell-penetrating peptides using mRNA display. Biotechnology J. 7, 387–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kamada H et al. (2007) Creation of novel cell-penetrating peptides for intracellular drug delivery using systematic phage display technology originated from Tat transduction domain. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 30, 218–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kondo E, Saito K, Tashiro Y, Kamide K, Uno S, Furuya T, Mashita M, Nakajima K, Tsumuraya T, Kobayashi N, Nishibori M, Tanimoto M, and Matsushita M. (2012) Tumour lineage-homing cell-penetrating peptides as anticancer molecular delivery systems. Nat. Comm. 3, 951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hammersh∅j P, Kumar EP, Harris P, Andresen TL, and Clausen MH. (2015) Facile Large-Scale Synthesis of 5-and 6-Carboxyfluoresceins: Application for the Preparation of New Fluorescent Dyes. European Journal of Organic Chemistry 2015, 7301–7309. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brglez J, Ahmed I, and Niemeyer CM. (2015) Photocleavable ligands for protein decoration of DNA nanostructures. Organic & biomolecular chemistry 13, 5102–5104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stahl PJ, Cruz JC, Li Y, Yu SM, and Hristova K. (2012) On-the-resin N-terminal modification of long synthetic peptides. Analytical biochemistry 424, 137–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Richelle GJ, Schmidt M, Ippel H, Hackeng TM, van Maarseveen JH, Nuijens T, and Timmerman P. (2018) A One-Pot “Triple-C” Multicyclization Methodology for the Synthesis of Highly Constrained Isomerically Pure Tetracyclic Peptides. ChemBioChem 19, 1934–1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.