Abstract

Diet plays a pivotal role in health outcomes, influencing various metabolic pathways and accounting for over 20% of risk-attributable disability adjusted life years (DALYs). However, the limited time during primary care visits often hinders comprehensive guidance on dietary and lifestyle modifications. This paper explores the integration of electronic consultations (eConsults) in Culinary Medicine (CM) as a solution to bridge this gap. CM specialists, with expertise in the intricate connections between food, metabolism, and health outcomes, offer tailored dietary recommendations through asynchronous communication within the electronic health record (EHR) system. The use of CM eConsults enhances physician-patient communication and fosters continuous medical education for requesting clinicians. The benefits extend directly to patients, providing access to evidence-based nutritional information to address comorbidities and improve overall health through patient empowerment. We present a comprehensive guide for CM specialist physicians to incorporate CM eConsults into their practices, covering the historical context of eConsults, their adaptation for CM, billing methods, and insights from the implementation at UT Southwestern Medical Center. This initiative delivers expanded access to patient education on dietary risks and promotes interprofessional collaboration to empower improved health.

Keywords: nutrition, dietary, communication, electronic medical record

Plain Language Summary

What you eat significantly impacts your health, affecting various aspects including weight, blood sugar, and inflammation. This paper highlights how health-related issues are linked to diet and presents one solution to help doctors guide patients more effectively. Often, the limited time during medical visits makes it challenging for doctors to provide detailed advice on lifestyle changes. Additional common barriers are that many doctors lack nutrition expertise, and access to nutrition experts such as registered dietitian nutritionists can be limited geographically and financially. This paper introduces the concept of electronic consultations (eConsults) in Culinary Medicine (CM) to help overcome this challenge. CM specialists are licensed healthcare professionals who understand how food influences the body and can use eConsults to offer personalized dietary recommendations. EConsults occur via a secure electronic medical record system that connects doctors and specialists, ensuring efficient communication. Patients benefit by gaining access to reliable nutritional information tailored to their specific health needs. This innovative approach also enhances communication between doctors and patients and helps doctors stay updated on the new research about how nutrition and food impact health. The paper provides a practical guide for doctors to integrate CM eConsults into their practices, making it easier to give valuable advice on dietary risks and promote healthier lifestyles. Overall, this initiative represents a significant step in improving patient nutrition education and fostering positive changes in health through the power of informed dietary choices.

Introduction

A suboptimal dietary pattern is a top risk factor for early death and disability in the United States. In 2016, dietary risks accounted for over 500,000 deaths, with the overwhelming majority attributable to cardiovascular disease.1 Similarly, dietary patterns are increasingly linked with a variety of chronic diseases, including diabetes, cancer, obesity, cognitive decline, and many autoimmune conditions.2–8 With this clear linkage between disease and reversible risk, nutritional interventions should occur at a wide scale to prevent the development of life-threatening illness. Unfortunately, there are numerous barriers facing physicians, which prevent them from addressing nutrition with patients, including lack of time, insufficient reimbursement for counseling, lack of training and confidence, and feelings of futility in treatment options.9,10 This dichotomy demonstrates the pressing need for novel and unconventional solutions.

Setting the Table for Innovation

Disruptive innovation can be defined as new approaches that enter an existing market, often with few resources, and eventually displace the status quo. Such innovation often emerges from unmet needs, demanding creativity and collaboration across sectors. CM is an evidence-based field that intersects the art of food and cooking with the science of medicine and nutrition, aiming to provide practical solutions when patients ask, “What should I eat?” in the context of their unique condition or prevention efforts.11 Beyond the scope of the average training a physician receives in nutrition, Certified Culinary Medicine Specialist (CCMS) physicians12 have additional training in culinary skills and food preparation, eating patterns and behaviors, and the mechanisms by which foods influence metabolism, immunity, pathophysiology, and well-being.11 This knowledge is invaluable for counseling patients to improve their health and connecting them to appropriate resources. However, access to this expertise remains limited especially when considering the enormity of burgeoning diet-sensitive disease.13

Leveraging Electronic Opportunity

Electronic consultations (eConsults) can provide a pathway for expansion of patient and clinician access to the knowledge base and expertise of applied nutrition in clinical care. In the United States, eConsults are clinician-to-clinician communications within an electronic health record (EHR) or another web-based platform. They are asynchronous, meaning a clinician can place a consult that does not have to be completed in real time by the specialist. When reviewing an eConsult request, a specialist contextualizes the patient’s medical history, recent relevant laboratory or imaging data, and unique circumstances or preferences. The specialist then responds to key questions asked by the requesting clinician and provides guidance for ongoing management of the patient. Once a specialist completes a written eConsult, the electronic health record delivers it back to the requesting clinician. The requesting clinician then communicates the results with the patient in the manner they deem most appropriate, such as by electronic portal message, telephone call, or follow-up visit. EConsults are intended to improve efficiency and quality of care by increasing access to specialty input and decreasing nonessential visits.14

Optimizing Collaboration in the Current Landscape

In most health system structures, nutrition questions are frequently presented to physicians. However, even with physician acknowledgement of the need for nutrition counseling, few physicians feel competent in providing this service to patients. One cross-sectional survey found that 71% of new interns entering internal medicine, surgical, or obstetric residencies report not feeling confident to effectively counsel patients on a healthy diet.15 Improvements in medical education that provide substantive nutrition counseling techniques will take years to see the manifestation of widespread changes in patient outcomes. Consequently, currently practicing physicians must rely on others who do have the competence and formal training to apply evidence-based nutritional knowledge to patient care.

An important and foundational approach to nutrition-based care includes consultation with registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs). However, access to dietitians is often limited by poor or absent reimbursement by current payer models16,17 and suboptimal multidisciplinary team communication and collaboration.18,19 In one study estimating unreimbursed costs for care coordination across multiple disciplines, RDN ranked 2nd highest for the quantity of nonbillable services provided.20 Due to these and other billing and reimbursement challenges, many RDNs offer self-pay options or focus on privately insured populations only, contributing to a lack of access for millions of Americans who could benefit from nutrition services.21

Fortunately, Affordable Care Act (ACA) regulations included nutrition services without copay for chronic disease prevention via nutrition counseling, but these rules are ever evolving with confusing variability among insurance payers.22 For example, some payors cover preventive nutrition counseling and counseling for certain conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, while others may not cover any nutrition-related care.22 Medicaid coverage for medical nutrition therapy varies from state to state in accordance with each state’s overall Medicaid plan. Medicaid plans are supposed to recognize medical nutrition therapy as an optional preventive care service to be covered under the ACA.22 In fact, some states do not recognize RDNs as Medicaid providers and thus will not reimburse for their services. Medicare, on the other hand, is uniform across states and offers coverage of RDN services under specific circumstances. Medicare Part B covers certain beneficiaries with diabetes, advanced kidney disease and kidney transplants that occurred within the previous 3 years. Primary care clinicians must be the ones to place a referral for Medicare to provide coverage.22

Due to these billing and reimbursement challenges as well as a lack of interprofessional strategy to improve access, many patients never have an opportunity to work with an RDN when facing conditions related to dietary pattern. The previously described gaps in physician nutrition education further widen the barriers to integration of nutrition strategy in routine medical care plans. Fortunately, creative collaboration between dietitian and physician teams with Culinary Medicine training provide a key opportunity for innovation in meeting the needs of patients with diet-sensitive disease through the design of a novel Culinary Medicine eConsult.

Approach

Rooted in the established concept of eConsults as an accessible, low-resource extension of traditional sub-specialty clinical models, the novel design described here of an interprofessional Culinary Medicine eConsult delivers written nutrition expertise tailored to a patient’s unique situation. Culinary Medicine eConsults specifically promote increased access to nutrition support for both primary care clinicians and specialists who seek guidance for meeting the nutritional needs of their patients. A Culinary Medicine eConsult leverages the combined expertise of a physician and registered dietitian team who can analyze a patient’s circumstances documented in the EHR, answer requesting clinician questions, and deliver recommendations that infuse dietary strategy as part of an overall care plan. CM specialist (CCMS) recommendations can benefit the management approach for many diseases including diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, obesity, and more. In addition to metabolic conditions with clear associations to unhealthy dietary patterns, Econsultation from CCMS clinicians can provide nuanced guidance including counseling, recipes, and practical information regarding access to local food resources. Other key areas of expert input include dietary management of celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity, other food sensitivity and allergy, osteoporosis, warfarin management, acid reflux, irritable bowel syndrome, and inflammatory bowel disease. EConsults in CM can significantly advance how nutrition knowledge is disseminated from clinician to patient, supporting clinicians delivering face-to-face care by providing evidence-based, tailored information to guide their plans and communication with patients.

Application to Patient Care

Fictional Case Study: DS

D.S., a 52-year-old man with hyperlipidemia who is chronically underweight and would like to gain weight, asks his physician for advice. He has tried doubling his dinner servings, which usually consist of a burger and French fries, a pork chop with mashed potatoes and carrots, or any variety of pasta with meat. He leads a mostly sedentary life as an accountant but walks a half-mile twice a day with his dog. His triglycerides are 265 mg/dL, LDL cholesterol is 147 mg/dL, and HDL cholesterol is 34 mg/dL. His hemoglobin A1C is 5.4%. What strategies could a physician recommend for weight gain that are also beneficial to metabolic health for this patient? And more importantly, if unsure of how to respond to this question, where could the physician caring for this patient turn to for help?

At many institutions, clinicians may turn to RDN colleagues for a patient referral and evidence-based advice, but financial and other access barriers limit this resource. To expand nutrition access beyond insurance barriers, creative innovation and collaboration remain essential. While these problems are multi-dimensional and complex, CM training offers tools and education that optimize the synergy of multidisciplinary collaboration in the pursuit of solutions. This manuscript describes the need for unique approaches and outlines the process of a physician-RDN team developed by the CM program at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center,23 utilizing eConsults as a patient care integration strategy. In this team context, a physician receives and responds to consultant questions about the role of diet in the patient’s care plan and collaborates with a certified culinary medicine specialist RDN to ensure inclusion of principles of medical nutrition therapy, access to local food resources (when need is indicated), and practical application to cooking. Although this method is not designed to replace more traditional one-on-one medical nutrition therapy from an RDN, it does offer one pathway to improve access to the specialty. Through this team-based consultation, RDNs contribute their expertise while physicians bill for reimbursable services.

Getting Paid for the “Curbside Consult”

Developing the process for the Culinary Medicine eConsult requires understanding the overall payment model relevant to eConsults for other specialties and recognition of the opportunity to reduce unreimbursed guidance. A common practice in patient care includes informal consults with clinician coworkers that have a particular interest or extensive knowledge in a particular domain, including nutrition. These informal consultations, while potentially beneficial in filling gaps, face significant potential drawbacks. Principally, they are unstructured and lack official documentation of the encounter in the EHR, leaving the requesting physician open to potential liability.24 Secondly, because these informal discussions typically happen either in person, via phone, or over email, experts fielding questions often lack crucial information about the patient’s medical history and relevant data that would be available in the medical record. Lastly, both the requesting clinician and the consultant dedicate time to respond, often needing to do additional research to give a thoughtful response without reimbursement for their efforts. EConsults offer a way to avoid these pitfalls and provide the path to a sustainable solution.

Private insurers in the United States reimburse for eConsults using various payment methods. For example, in one 2016 pilot program within the LA Health Care Plan, specialists were paid $45 per consult, and primary care physicians received a monthly stipend for participation.25 In the Champlain system in Ontario, Canada, specialists were reimbursed for time spent (0–10, 10–15, or 15–20 minutes) with the rate based at $200/hour.25 Many of the private payers use a transactional payment for both primary care physician and specialist per consult. Creative and varied reimbursement models for specialty eConsults continue to expand in the private sector, but to further improve access to patients, eConsults require federal support.

In 2019, The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in the United States added two new codes for eConsults under the telehealth services umbrella.26 The code 99452 describes the work of the requesting physician when initiating a consultation and managing the response. For the consultant, the code 99451 covers the expert response time. Reimbursement for the requesting physician requires a minimum time spent of over 15 minutes, including preparation for the consultation, communicating with the consultant and providing feedback and information to the patient. CMS also requires verbal consent for the consultation documented in the patient’s medical record. The consultant code requires a minimum of 5 minutes spent in response, which can include time reviewing pertinent medical records, lab/imaging studies, medication profile, and context of consult, in addition to consultative verbal or electronic record discussion with the requesting clinician. Consultants can bill eConsult services to the same patient no more than one time in a seven-day period.27 In-person office visits with the consultant cannot be billed within the two weeks following the consultation request.

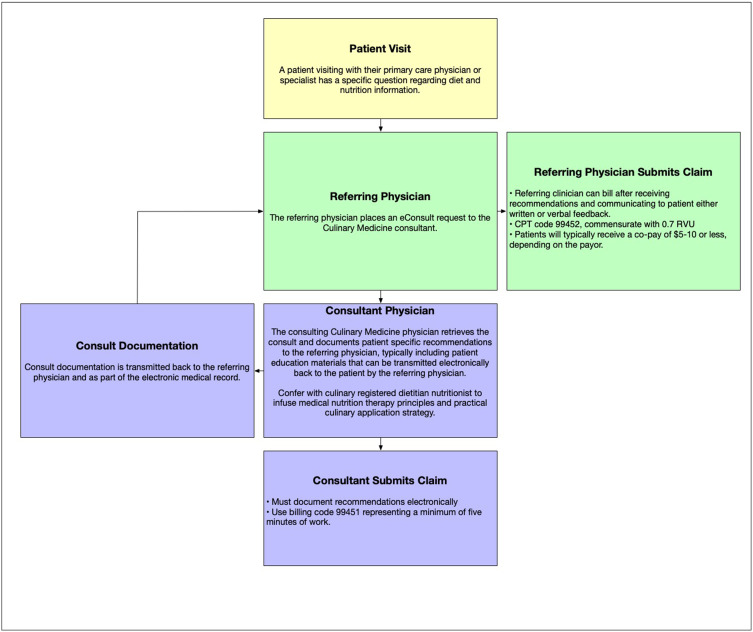

To implement an eConsult for CM, the CM team first engaged institutional administrators and the electronic health record and billing teams. Once the EHR is set up for this type of consult in other contexts, as is likely the case for most US-based health systems, the application to a new specialty is straightforward. For US-based billing, the CPT code is 99452 for the requesting physician and mandates they have spent a total of 15 minutes or more on preparation time and chart review, including communication back to the patient after the consulting physician has responded to the consult. The CPT code is 99451 for the consulting physician, reflecting a minimum of 5 minutes’ worth of work. Each of these codes are reimbursed at 0.7 RVU (relative value units), which is the equivalent value of an established outpatient visit that lasts 10–19 minutes.23 See Figure 1 for process graphic that outlines the process of consultation.

Figure 1.

eConsult Referral Process Diagram.

eConsults in Practice

In the case of D.S., the referring physician could ask for a CM eConsult in the EHR, documenting patient consent. The consultant will then receive this via a task assignment in the EHR. Consultants must document their recommendations electronically and use the billing code 99451 representing a minimum of 5 minutes of work. The referring clinician can also bill once they have received the consult recommendations and communicated them back to the patient. Using CPT code 99452, the referring physician will be reimbursed commensurate with 0.7 RVU reflecting prep time and review of greater than 15 minutes. Patients may receive a co-pay, typically $5-10 or less, depending on the payor.

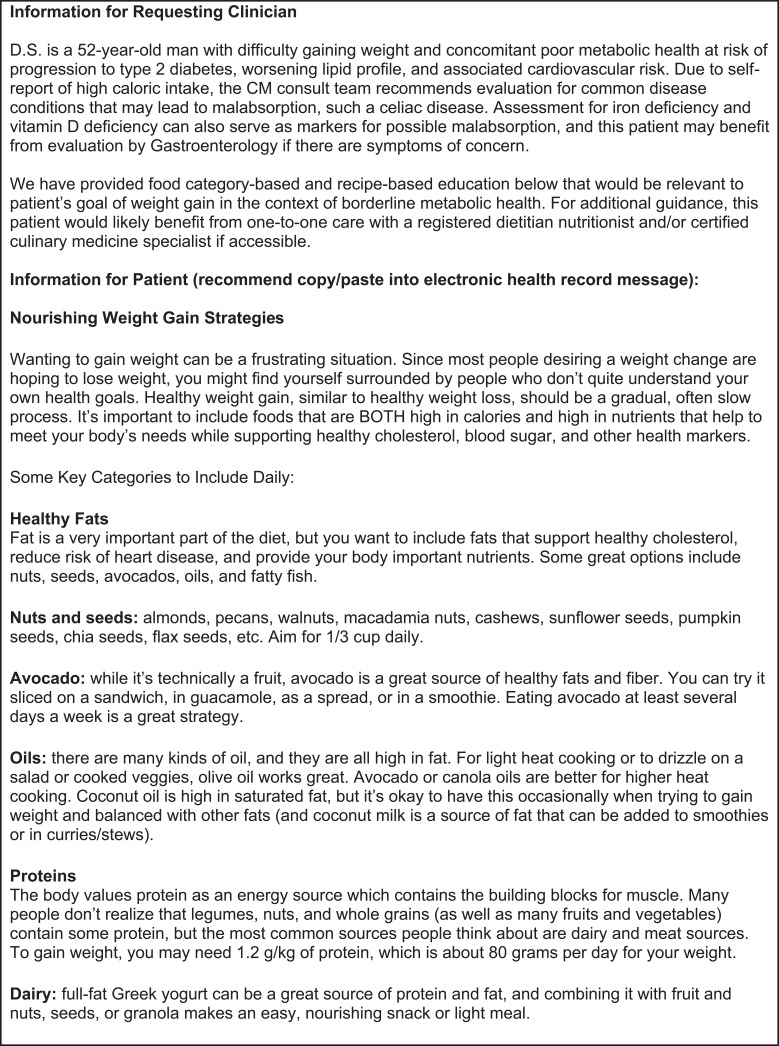

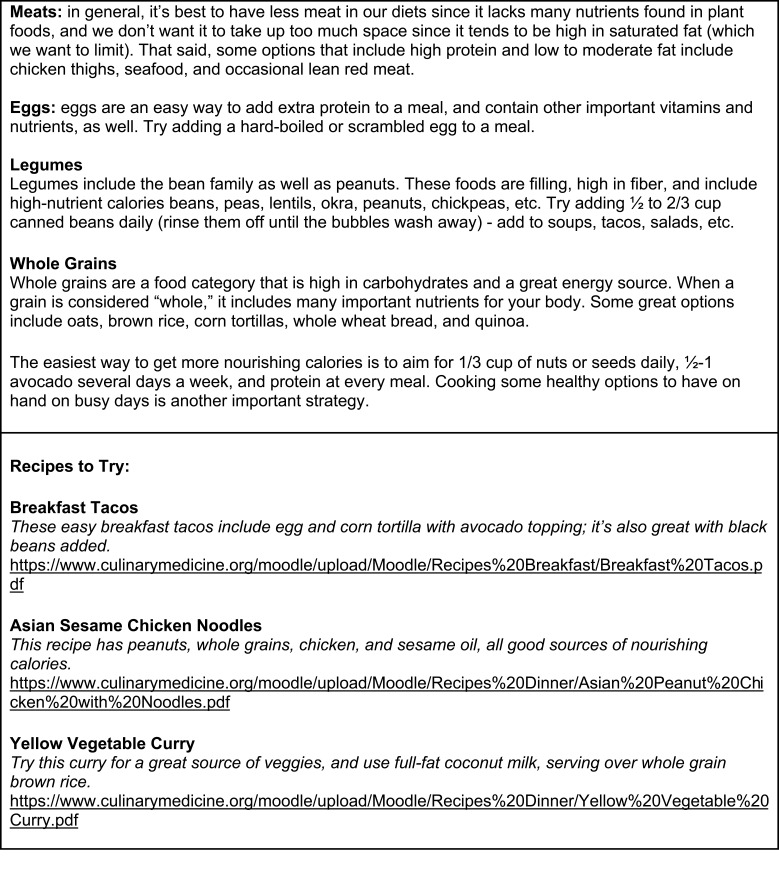

Figure 2 details a typical eConsult approach and reflects a possible response that would benefit the fictional case study of D.S. While the first iteration of an eConsult on a new topic may take the consulting team 30 to 45 minutes, topic repeat then enables re-use of similar content. This allows tailoring of previously created content to a specific patient’s needs in a brief 5 to 10-minute timeframe.

Figure 2.

Continued.

Figure 2.

Example eConsult Response to Case Study from CCMS Consultant Team.

Discussion

The delivery of nutrition education and integration into the practice of medicine necessitates sweeping change. Culinary Medicine eConsults offer a low resource, accessible path forward to extend the reach of nutrition advice to patients, while supporting proper reimbursement for consultants. CM eConsults provide a framework to enhance multidisciplinary care with an emphasis on patient empowerment.

Multi-Sector Benefits of CM eConsults

Aside from the obvious benefit of appropriate reimbursement, there are numerous other advantages to participating in a Culinary Medicine eConsult system. First, they promote better communication amongst multidisciplinary clinicians while aligning with the emerging shifts towards telemedicine and virtual care that accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the context of a physician-RDN partnership, the eConsult in CM encourages a team-based approach to care. In one study describing qualitative perception of eConsults among primary care clinicians, the authors report increased satisfaction secondary to fewer face-to-face consultations, more efficient medication management, expedited diagnostic testing in lieu of or in preparation for a specialty visit, and more effective communication with specialists.14 Aside from these advantages, eConsults also have far-reaching effects for healthcare systems, individual clinicians, and most importantly, patients.

Benefits for Hospital Systems

In hospitals, eConsults introduce the potential to increase access to and streamline specialty care. EConsults are of particular importance in large safety net systems facing persistent barriers to specialist availability and prompt access. In the year following implementation of eConsults in the NYC Health and Hospital system, they successfully resolved 13% of specialty referrals without direct patient contact, thus reducing wait times and improving strain on safety net resources.28 EConsults may be especially useful for primary care clinicians practicing in rural or resource limited areas that do not have many nutrition-specific experts.29 For primary care practices, the geographic distance between themselves and hospital-based specialists generally precludes access to specialist input through informal conversations. PCPs also reported requesting eConsults in situations where they previously might not have pursued specialist input due to barriers to seeking input from a specialist colleague and when formal referral of the patient for face-to-face visit did not seem indicated.29 Thus, eConsults offers improved management of consultative services and support provision of an appropriate “dose” of input from specialists.

Benefits for Physicians

There are many benefits of Culinary Medicine eConsults for consulting physicians. The principal among them is flexibility. Since eConsults are asynchronous, they can be done at the consultant’s convenience, which is often not possible with informal consults when a provider is compelled to deliver a solution in real time. The asynchronous nature affords physicians the time they need to formulate a thoughtful response, engage RDN partners, and include a brief review of recent literature and patient chart review. The time to complete eConsults is usually less than 15 minutes but can be longer depending on the patient and situational complexity.30 Finally, it does not require face-to-face visits with patients, decreasing wait times for other patients who would need that additional level of in-person care. One multi-center study assessing the effect of eConsult implementation found an adjusted 8.2-day shorter wait time for in-person appointments following eConsult adoption.28

Improved clarity of communication with other clinicians proves to be another benefit of eConsults by creating easier professional relationships and decreasing potential liability. In responding to this question of liability, one PCP noted,

Before … if [there] was a phone call or an email, I would have to write in the note, well, Dr. So-and-so on a phone conversation recommended this… and if I get that wrong … I could be setting up my specialist consultants with a problem that really was just my misinterpretation of what they told me.24

Utilizing eConsults ensures that all care team members can review the actual patient record for official documentation, avoiding miscommunication and creating a longitudinal record.

Physicians are encouraged to be lifelong learners. eConsults in CM provide an opportunity for continuous learning about nutrition in real time. After receiving recommendations from a consultant, the requesting physician must in turn share this information with their patient, giving them the opportunity to absorb the information - and engage in further research, if warranted. The next time they have a similar clinical question, they will be better equipped to answer it on their own and may not have to request subsequent consultation. Utilizing CM eConsults adds value to the care PCPs provide, which can translate into high patient satisfaction scores, revenue, an additional pathway to meet RVU targets, and referrals. Secondarily, aside from delivering eConsults, CCMS experts can provide nutritionally relevant pathways to explore patient diagnoses that may not have already been considered. In the case of the chronically underweight patient, D.S., it would be appropriate for the consulting CCMS clinician to recommend that the requesting physician consider investigating underlying diseases such as celiac disease, vitamin D deficiency, and/or iron deficiency, in addition to implementation of a dietary pattern with high quality nutrition. This type of communication fosters a team-based approach that leads to better outcomes and improved patient care, and the eConsult model provides the dedicated time and reimbursement for the consultant to deliver a more thoughtful, thorough response than what may occur informally.

A final, important benefit to physicians is the ability to be reimbursed for the virtual encounter. One eConsult delivers 0.7 RVUs for both the requesting and consulting physicians. Although on an individual basis it’s not much, these visits add up over time. Additionally, both the requesting and consulting physician can submit a claim for their services, ensuring that the requesting physician is also compensated for their time communicating with the patient. Over time, CCMS clinicians can build a database of responses for commonly asked questions that they can tailor to individual patient needs. This allows for more efficient use of physician time and energy, providing counseling to a larger patient population and receiving appropriate compensation.

Benefits for Patients

Patients have much to gain from eConsults in CM. One study assessing the barriers and facilitators to the implementation of eConsults found that from the patient perspective, eConsults had the potential to improve their care through more timely access to specialists, especially for those living in remote locations, and eConsults also carried the potential for increased cost savings.31 With reduced reliance on face-to-face visits that can instead be answered electronically, patients can minimize time missed from work as well as travel and childcare costs.29 Additionally, with CM eConsults receiving specialized nutrition recommendations with actionable steps for the patient to take, such as recipes they can try to make at home, or community resources that will support their health goals, patients are able to take charge of this aspect of their well-being. CCMS clinicians provide written validation and support in their electronic communications with patients and to referring physicians, acknowledging that nutritional change is hard, but they have a whole team behind them, ready to help them make those changes.

Limitations

While there are clearly many benefits to eConsults, there are a few important limitations to consider when implementing this system. Primarily, it may seem that this role for physicians doing culinary education may encroach on the work of RDNs. It is important to remember that eConsults are not a substitute for one-to-one RDN consultations. Instead, they carve out a niche of patients that RDNs are unable to reach due to current reimbursement models, thus providing important knowledge to a broader group of patients needing support. Through the CM eConsult, many patients (and some PCPs) may be receiving their first exposure to an RDN. Additionally, a team-based approach is tantamount to eConsults and creates an opportunity to elevate the work and expertise of RDNs. In fact, a CCMS-trained physician/dietitian team become the ideal combination of expertise, perspective, and ability to bill for services.

Another limitation is the potential amount of time needed to craft a thoughtful response to a consultant question. This can be ameliorated though secure, editable, shareable databases where previously made content can be utilized by multiple clinicians, customized to the specific clinical question and updated as needed to reflect the latest evidence. Additionally, resources such as patient handouts, recipes, and local resources should be curated. These best practices streamline the consultant’s efforts, resulting in peak efficiency over time.

Finally, the implementation of this clinical model occurred in the United States and thus reflects US-based billing models with overlap in Canada, as discussed. This limits immediate applicability to other countries with different payor systems, but the described interprofessional approach contributes broad relevance as a strategy to expand patient access to clinical nutrition guidance.

Future Directions and Lessons Learned

While the framework of eConsults is in place at some institutions, CM-specific eConsults are currently rare. Individual physician champions or institutions will need to develop their own approach to instituting eConsults. At UT Southwestern, the physician initially contacted the Director of Health Systems Emerging Strategies, a position many hospital systems have, to pitch building CM eConsults. While it may be a slow start, building a coalition of clinicians who will advocate for the benefits of eConsults can mobilize momentum toward the desired outcome. Additionally, staying flexible and adaptable will allow for proper integration of an eConsult system in whatever fashion best fits the context and mission of the institution.

The widespread implementation of electronic consultations in the United States is a convenient and low resource way to improve patient access to nutrition and further build the brand of CM, thus opening the door for future innovation. EConsults can be used to stratify patients based on need for additional nutritional or culinary support, which can be met either through other clinical innovations, such RDN-led nutrition counseling, shared medical visits, or a one-to-one consultation with a CM team member.

For a patient like D.S., after giving written advice with dietary suggestions through an eConsult, the consultant would likely recommend that he may benefit from an individualized visit with a CCMS expert. With a live or virtual teaching kitchen experience available, he could learn techniques regarding how to prepare meals with different types of fat sources, how to increase nourishing ingredients in meals, such as legumes, and how to build flavor, such as use of more herbs or spices. These changes have the potential to increase fiber intake, reduce saturated fat and sodium intake, and enhance nourishing ingredients that reduce inflammation and cardiovascular risk. This tailored way of infusing cooking with medicine will better arm D.S. with the tools he needs to gain weight in a healthy manner.

Conclusion

Creating an eConsult service for CM is an approach meant to appropriately reimburse for unique expertise, encourage multidisciplinary teamwork and increase access to nutrition counseling for patients. Aside from these benefits, eConsults are a way to build the brand of CM as clinical care, an emerging field that utilizes evidence-based nutrition interventions to improve patient and population health. With both primary care physicians and specialists able to request consultation from these specialized physicians, ideally partnered with RDNs, the mission of CM advances.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.U. S. Burden of Disease Collaborators, Mokdad AH, Ballestros K, Echko M, et al. The State of US Health, 1990-2016: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors among US States. JAMA. 2018;319(14):1444–1472. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aridi YS, Walker JL, Wright ORL. The association between the Mediterranean dietary pattern and cognitive health: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2017;9(7):674. doi: 10.3390/nu9070674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aune D, Giovannucci E, Boffetta P, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality-A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(3):1029–1056. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhat S, Coyle DH, Trieu K, et al. Healthy food prescription programs and their impact on dietary behavior and cardiometabolic risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Nutr. 2021;12(5):1944–1956. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmab039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Botchlett R, Woo SL, Liu M, et al. Nutritional approaches for managing obesity-associated metabolic diseases. J Endocrinol. 2017;233(3):R145–R171. doi: 10.1530/JOE-16-0580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chander AM, Yadav H, Jain S, Bhadada SK, Dhawan DK. Cross-talk between gluten, intestinal microbiota and intestinal mucosa in celiac disease: recent advances and basis of autoimmunity. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2597. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang FF, Cudhea F, Shan Z, et al. Preventable cancer burden associated with poor diet in the United States. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019;3(2):pkz034. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pkz034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells JC, Sawaya AL, Wibaek R, et al. The double burden of malnutrition: aetiological pathways and consequences for health. Lancet. 2020;395(10217):75–88. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32472-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aggarwal M, Devries S, Freeman AM, et al. The deficit of nutrition education of physicians. Am J Med. 2018;131(4):339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed NU, Delgado M, Saxena A. Trends and disparities in the prevalence of physicians’ counseling on diet and nutrition among the U.S. adult population, 2000-2011. Prev Med. 2016;89:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.La Puma J. what is culinary medicine and what does it do? Popul Health Manag. 2016;19(1):1–3. doi: 10.1089/pop.2015.0003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The American College of Culinary Medicine. The Certified Culinary Medicine Specialist Program. https://culinarymedicine.org/certified-culinary-medicine-specialist-program/. Accessed August 29, 2022.

- 13.Downer S, Berkowitz SA, Harlan TS, Olstad DL, Mozaffarian D. Food is medicine: actions to integrate food and nutrition into healthcare. BMJ. 2020;369:2482. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupte G, Vimalananda V, Simon SR, DeVito K, Clark J, Orlander JD. Disruptive innovation: implementation of electronic consultations in a veterans affairs health care system. JMIR Med Inform. 2016;4(1):e6. doi: 10.2196/medinform.4801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frantz DJ, McClave SA, Hurt RT, Miller K, Martindale RG. Cross-Sectional Study of U.S. Interns Perceptions of Clinical Nutrition Education. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;40(4):529–535. doi: 10.1177/0148607115571016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braunstein N, Guerrero M, Liles S, et al. Medical nutrition therapy for adults in health resources & services administration-funded health centers: A call to action. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2021;121(10):2101–2107. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2020.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jortberg BT, Parrott JS, Schofield M, et al. Trends in registered dietitian nutritionists’ knowledge and patterns of coding, billing, and payment. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2020;120(1):134–145 e133. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2019.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yinusa G, Scammell J, Murphy J, Ford G, Baron S. Multidisciplinary provision of food and nutritional care to hospitalized adult in-patients: a scoping review. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:459–491. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S255256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuppersmith NC, Wheeler SF. Communication between family physicians and registered dietitians in the outpatient setting. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102(12):1756–1763. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(02)90378-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ronis SD, Grossberg R, Allen R, Hertz A, Kleinman LC. estimated nonreimbursed costs for care coordination for children with medical complexity. Pediatrics. 2019;143(1). doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ulatowski K. Guide to Insurance and Reimbursement.Today’s Dietitian. 2017. Great Valley Publishing Company;19:40. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Does Insurance Cover Nutritionists? State Requirements for Nutrition and Dietitian Fields.Website available from: https://www.nutritioned.org/insurance-cover-nutritionists/. Accessed February 2, 2023.

- 23.Albin JL, Siler M, Kitzman H. Culinary medicine econsults pair nutrition and medicine: A feasibility pilot. Nutrients. 2023;15(12):2816. doi: 10.3390/nu15122816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson E, Vimalananda VG, Orlander JD, et al. Implications of electronic consultations for clinician communication and relationships: a qualitative study. Med Care. 2021;59(9):808–815. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blue Shield of California Foundation and Center for Connected Health Policy. Electronic consults offer clear benefits to patients and providers that must be conveyed to improve reimbursement and increase access to specialty care.Available from: https://blueshieldcafoundation.org/sites/default/files/u19/eConsult%20GPS_032916.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed February 2, 2023.

- 26.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Program: Revisions to payment policies. National Archives.Available from: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/11/23/2018-24170/medicare-program-revisions-to-payment-policies-under-thephysician-fee-schedule-and-other-revisions. Accessed February 3, 2023.

- 27.Murray DL 2 new codes developed for interprofessional consultation. Coding Corner website. https://www.aappublications.org/news/2019/01/04/coding010419. Published 2019. Accessed February 3, 2023.

- 28.Gaye M, Mehrotra A, Byrnes-Enoch H, et al. Association of eConsult Implementation with access to specialist care in a large urban Safety-Net System. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(5):e210456. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greiwe J. Telemedicine in a post-covid world: how econsults can be used to augment an allergy practice. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(7):2142–2143. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vimalananda VG, Gupte G, Seraj SM, et al. Electronic consultations (e-consults) to improve access to specialty care: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. J Telemed Telecare. 2015;21(6):323–330. doi: 10.1177/1357633X15582108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Osman MA, Schick-Makaroff K, Thompson S, et al. Barriers and facilitators for implementation of electronic consultations (eConsult) to enhance access to specialist care: a scoping review. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(5):e001629. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]