Abstract

We present a case of an adult male who presented with pancytopenia accompanied by symptomatic anemia, necessitating chronic transfusions. He was diagnosed with systemic mastocytosis with an associated hematologic neoplasm. Following an inadequate response to midostaurin therapy, the patient was initiated on the newly approved avapritinib. The patient showed significant improvements in all three blood cell lines; however, he developed leg edema, blepharedema, and gum bleeding on this medication. This case underscores the intricacies of managing a patient with advanced systemic mastocytosis, the emerging role of highly selective KIT inhibition in its treatment, and the practical management of adverse medication effects.

Keywords: systemic mastocytosis with an associated clonal hematological non-mast cell lineage disease (sh-ahnmd), targeted therapeutics, molecular target therapies, tyrosine kinase receptor inhibitors, systemic mastocytosis

Introduction

Mastocytosis, a rare disorder, is characterized by the clonal proliferation of mast cells in diverse organs throughout the body. These aberrant mast cells amass in the bone marrow, skin, liver, spleen, and other organs, yielding a heterogeneous clinical spectrum [1]. This ranges from restricted disease (cutaneous mastocytosis), primarily observed in the pediatric population, to a more aggressive variant with extracutaneous involvement (systemic mastocytosis) [2]. The latter is predominantly found in adult patients and, in rare instances, manifests as a malignant solid tumor marked by destructive growth, termed mast cell sarcoma [3].

While systemic mastocytosis is more prevalent among adults, it can manifest without skin involvement and affect individuals of any age [4]. This presents distinctive challenges for diagnosis and management. The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies five subcategories of systemic mastocytosis: indolent systemic mastocytosis, smoldering systemic mastocytosis, aggressive systemic mastocytosis, systemic mastocytosis with associated hematologic neoplasm, and mast cell leukemia [3]. The latter three represent advanced systemic mastocytosis (AdvSM), a condition with a poor prognosis with a median overall survival (OS) ranging over four years [5].

The clinical diagnosis of SM starts with a bone marrow biopsy, as this site is most frequently impacted by mastocytosis [6]. The presence of multifocal dense mast cell aggregates in histology is a major criterion for diagnosis [7]. Additional analyses involve immunotyping for CD25 and/or CD2 expression on abnormal mast cells, serum levels of tryptase [8], and molecular DNA testing for KITD816V mutation [9]. In cases presenting with blood eosinophilia, FIP1L1-PDGFRA testing is pertinent [10]. The combination of these facilitates the subcategorization of SM, guiding both prognostic assessment and therapeutic decision-making.

The management of systemic mastocytosis (SM) is notably tailored to each individual, factoring in the specific subtype, extent of organ involvement, and patient's risk profile. Treatment approaches include observation alone, symptom management (e.g., antihistamines, proton pump inhibitors), supportive measures (e.g., red blood cell transfusions, osteoporosis treatment), cytoreductive therapy (e.g., interferon alpha, cladribine) [11], and targeted tyrosine kinase inhibition (e.g., midostaurin, imatinib, avapritinib) for mast cell debulking, especially in cases of aggressive or treatment-resistant disease [12]. Other options include interferon-a in individuals who are not candidates for tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (eg, older adults), but the response to it is generally slower [13].

In this report, we detail a case of a 67-year-old male who presented with pancytopenia accompanied by symptomatic anemia necessitating transfusions. A bone marrow biopsy confirmed systemic mastocytosis with an associated hematologic neoplasm. Following an inadequate response to midostaurin therapy, the patient was initiated on the newly approved avapritinib. Notably, this shift led to a significantly improved response to the treatment.

Case presentation

A 67-year-old male, with a medical history of moderate intellectual disability, essential hypertension, mixed hyperlipidemia, osteoporosis, and mild cataracts bilaterally, initially presented due to pancytopenia requiring frequent transfusions to manage symptomatic macrocytic anemia. At presentation, he had a hemoglobin level of 6.4 gm/dL, platelets 120 K/μL, WBC 3.4 K/μL, and absolute neutrophil count (ANC) 1900. His initial diagnostic investigations, including assessments of iron levels, B12, folate, serum and urine protein electrophoresis (SPEP, UPEP), immunofixation studies, and free light chain assays, all yielded normal results.

Subsequently, a bone marrow biopsy was performed, revealing hypercellular bone marrow with granulocytic hyperplasia with slightly left-shifted maturation. findings indicative of myelodysplastic syndrome with multilineage dysplasia (MDS-MLD). He was initiated on erythrocyte stimulating agents (RetacritTM), titrated up to 40,000 units weekly. Despite this treatment, he continued to require frequent transfusions every four weeks.

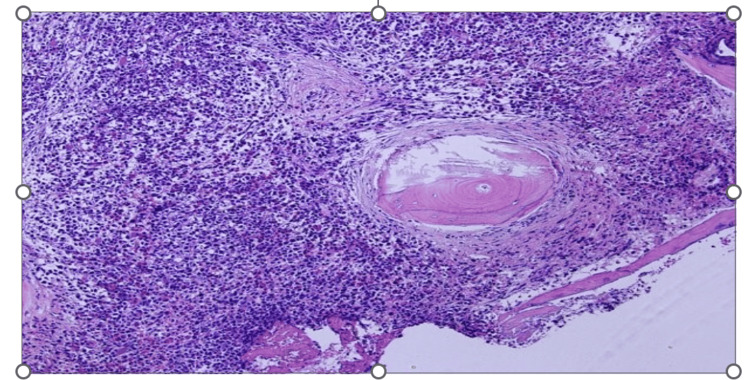

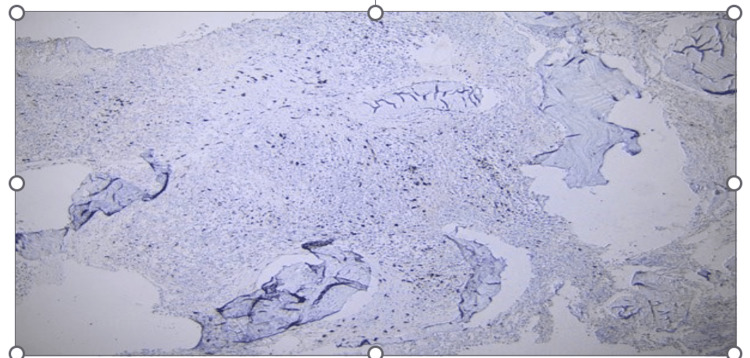

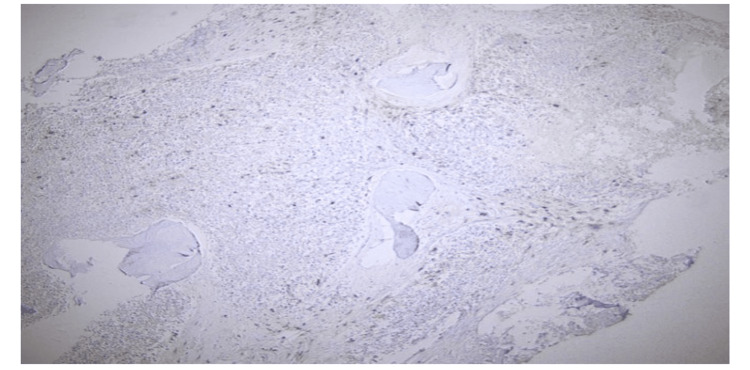

A follow-up bone marrow biopsy conducted a year later unveiled a myeloid neoplasm with grade 3 myelofibrosis. Notably, atypical mast cell aggregates (Figure 1) were observed, which were positive for CD117 (Figure 2), CD25 (Figure 3), and CD2 (partially, weakly). Molecular analysis confirmed the presence of a KITD816V mutation while elevated serum tryptase levels reached 117 μg/L (Normal 0-11.4). Collectively, these findings were consistent with a diagnosis of systemic mastocytosis with an associated hematological neoplasm.

Figure 1. H&E sections showing clustered spindle-shaped mast cells.

Figure 2. Neoplastic mast cells showing CD117 reactivity .

Figure 3. Neoplastic mast cells showing CD25 reactivity .

The patient was not a candidate for a bone marrow transplant because of his comorbid conditions and functional status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 2). Hence, treatment with midastaurin was initiated and gradually titrated up to 100 mg q12h, which yielded limited results as he continued to necessitate transfusions every four weeks. After three months, he transitioned to avapritinib 50 mg, in line with current trends in practice, it was gradually escalated to 200 mg daily, which elicited a favorable response. He received supportive transfusions to keep his platelet count above 50 K/uL. His transfusion requirements abated for a period of five months with an improvement of hemoglobin from 6 g/dl to 12 g/dl, platelets from <20K/uL to >300k/uL, and serum tryptase level from 117 ug/l to 11 ug/l. However, the emergence of side effects, including left eye blepharedema and tearing, lower extremity edema, and gum bleeding, prompted the suspension of avapritinib. Following a reduced dose of 100 mg daily, the patient's tolerance improved, and he experienced a notable enhancement in fatigue and generalized weakness. Currently, he has sustained this reduced dosage for four months without requiring further transfusions.

Discussion

Guidelines suggest either midostaurin or avapritinib; however, midostaurin is often the preferred first-line treatment for patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis due to its superior risk/benefit profile when compared to alternative therapies and provider experience with the drug. Functioning as a multi-kinase inhibitor, midostaurin not only targets c-KIT mutations but also other signaling pathways believed to be involved in mast cell activation [14]. The prominence of the KIT D816V driver mutation, observed in 90% to 95% of patients with systemic mastocytosis, makes it a very attractive therapeutic target [15].

Midostaurin was the first KIT inhibitor to undergo evaluation for systemic mastocytosis treatment. It yielded remarkable reductions in bone marrow mast cell burden, serum tryptase levels, and splenomegaly [5]. Additionally, it led to substantial enhancements in the quality of life, mitigating symptoms except for nausea and vomiting, which are recognized as common midostaurin-related adverse effects [14]. The compelling data resulting from these outcomes culminated in the FDA and EMA's 2017 approval of midostaurin for systemic mastocytosis treatment [16], thereby setting a significant milestone in response and survival benchmarks utilizing KIT inhibition for this condition.

Within the landscape of tyrosine kinase inhibitors, avapritinib emerges as a distinct contender, demonstrating heightened selectivity for the inhibition of D816V-mutated KIT and PDGFRA A-loop mutants when compared with midostaurin [17]. Its in vitro potency, exhibiting a 10-fold greater efficacy, underscores its potential [17]. The phase 1 EXPLORER study [18] and phase 2 PATHFINDER study [19] presently evaluate avapritinib's clinical efficacy and safety. A comprehensive evaluation combining outcomes from EXPLORER and PATHFINDER against patients receiving the best available therapy reveals that avapritinib-treated individuals exhibited significantly enhanced survival. These patients also showed the largest reductions in serum tryptase levels [20]. Furthermore, a matching-adjusted, indirect treatment comparison between the participants of midostaurin and avapritinib trials further solidified the statistically significant improvement in overall response rates, complete response rates, and survival for avapritinib over midostaurin [21].

Analysis of the phase II PATHFINDER study unveils reductions of 50% or more from baseline in serum tryptase (93%), bone marrow mast cells (88%), and KIT D816V allele frequency (60%). Impressively, 30% of patients achieved molecular remission of KIT D816V, signifying a groundbreaking advancement in the treatment of advanced systemic mastocytosis [22]. These robust outcomes ultimately led to the FDA's approval of avapritnib in 2021 for adult patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis [23]. The most encountered adverse reactions in individuals with advanced systemic mastocytosis included thrombocytopenia, anemia, neutropenia, periorbital/peripheral edema, diarrhea, nausea, fatigue/asthenia, and cognitive and other CNS side effects [19]. When initiating the treatment, the bone marrow suppressions associated with avapritinib can pose clinical challenges for physicians in treating patients with low cell counts at baseline. Patients who have cytopenias at the time of initiation of treatment are at increased risk of bone marrow suppression [19]. In the Phase 1 EXPLORER trial, the risk of grade 3 or higher thrombocytopenia was 20% in the patients without baseline cytopenia, however, this risk was increased to up to 70% in patients who had thrombocytopenia at baseline [18]. It's important to note that Avapritinib is not recommended for patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis if their platelet counts fall below 50 K/μL due to the risk of worsening cytopenias and intracranial hemorrhage [23]. In our patient, avapritinib was initiated at the dose of 50 mg and slowly escalated with supportive platelet transfusions to keep the counts above 50 K/μL.

Conclusions

This case contributes valuably to the growing body of evidence in support of avapritinib's use in advanced systemic mastocytosis. Its remarkable capability to achieve molecular remission of c-kit mutations highlights the direct correlation between heightened c-kit selectivity and potency. Establishing standards for molecular monitoring of KIT D816V and embracing the concept of minimal residual disease (MRD) in advanced systemic mastocytosis is of great importance. Equally noteworthy is BLU-263, a KIT D816V inhibitor demonstrating equipotency with avapritinib in vitro. Its minimal central nervous system penetration suggests the potential for fewer central nervous system side effects. As we continue refining highly selective inhibition for conditions defined by driver mutations, the landscape holds promise for transformative changes in aggressive and lethal diseases.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: Ngowari Pokima, Muhammad Niazi, Qun Dai

Drafting of the manuscript: Ngowari Pokima, Georges Khattar, Praneeth R. Keesari, Salman Khan, Qun Dai, Nnedindu Asogwa

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Ngowari Pokima, Georges Khattar, Praneeth R. Keesari, Salman Khan, Muhammad Niazi, Ruifang Zheng, Qun Dai, Nnedindu Asogwa

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Georges Khattar, Praneeth R. Keesari, Salman Khan, Muhammad Niazi, Ruifang Zheng, Nnedindu Asogwa

Supervision: Qun Dai

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

References

- 1.Mastocytosis: 2016 updated WHO classification and novel emerging treatment concepts. Valent P, Akin C, Metcalfe DD. Blood. 2017;129:1420–1427. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-731893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. Hartmann K, Escribano L, Grattan C, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li W. Bisbane. Brisbane (AU): Exon Publications; 2022. The 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Hematolymphoid Tumors. Leukemia. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epidemiology, prognosis, and risk factors in mastocytosis. Brockow K. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2014;34:283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Efficacy and safety of midostaurin in advanced systemic mastocytosis. Gotlib J, Kluin-Nelemans HC, George TI, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2530–2541. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Standards and standardization in mastocytosis: consensus statements on diagnostics, treatment recommendations and response criteria. Valent P, Akin C, Escribano L, et al. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37:435–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diagnosis of mastocytosis: general histopathological aspects, morphological criteria, and immunohistochemical findings. Horny HP, Valent P. Leuk Res. 2001;25:543–551. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(01)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diagnostic value of immunostaining for tryptase in patients with mastocytosis. Horny HP, Sillaber C, Menke D, et al. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:1132–1140. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199809000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mutation analysis of C-KIT in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes without mastocytosis and cases of systemic mastocytosis. Fritsche-Polanz R, Jordan JH, Feix A, Sperr WR, Sunder-Plassmann G, Valent P, Födinger M. Br J Haematol. 2001;113:357–364. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beham-Schmid C, Schmitt-Graeff A. Bone Marrow Biopsy Pathology. Essentials of Diagnostic Pathology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2020. Myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms with eosinophilia and rearrangement of PDGFRA, PDGFRB, FGFR1, or with PCM1-JAK2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cytoreductive therapy in 108 adults with systemic mastocytosis: outcome analysis and response prediction during treatment with interferon-alpha, hydroxyurea, imatinib mesylate or 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine. Lim KH, Pardanani A, Butterfield JH, Li CY, Tefferi A. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:790–794. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inhibitory effects of midostaurin and avapritinib on myeloid progenitors derived from patients with KIT D816V positive advanced systemic mastocytosis. Lübke J, Naumann N, Kluger S, et al. Leukemia. 2019;33:1195–1205. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0450-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Treatment of adult systemic mastocytosis with interferon-alpha: results of a multicentre phase II trial on 20 patients. Casassus P, Caillat-Vigneron N, Martin A, et al. Br J Haematol. 2002;119:1090–1097. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Midostaurin in advanced systemic mastocytosis. Chandesris MO, Damaj G, Canioni D, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2605–2607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1515403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avapritinib, a potent and selective inhibitor of KIT D816V, improves symptoms of advanced systemic mastocytosis (AdvSM): analyses of patient reported outcomes (PROs) from the phase 1 (EXPLORER) study using the (AdvSM) symptom assessment form (AdvSM-SAF), a new PRO questionnaire for (AdvSM) Gotlib JR, Radia D, DeAngelo DJ, et al. Blood. 2018;132:351. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schlenk RF, Kayser S. Small Molecules in Hematology. Vol. 212. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018. Midostaurin: a multiple tyrosine kinases inhibitor in acute myeloid leukemia and systemic mastocytosis; pp. 199–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.A precision therapy against cancers driven by KIT/PDGFRA mutations. Evans EK, Gardino AK, Kim JL, et al. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aao1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Safety and efficacy of avapritinib in advanced systemic mastocytosis: the phase 1 EXPLORER trial. DeAngelo DJ, Radia DH, George TI, et al. Nat Med. 2021;27:2183–2191. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01538-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MPN- 395: efficacy and safety of≤ 200 mg avapritinib in patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis: pooled results from the phase 1 EXPLORER and interim phase 2 PATHFINDER studies. Radia D, DeAngelo D, Deininger MW, et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021;21:367–368. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Efficacy of avapritinib versus best available therapy in the treatment of advanced systemic mastocytosis. Reiter A, Gotlib J, Álvarez-Twose I, et al. Leukemia. 2022;36:2108–2120. doi: 10.1038/s41375-022-01615-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Indirect treatment comparisons of avapritinib versus midostaurin for patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis. Pilkington H, Smith S, Roskell N, Iannazzo S. Future Oncol. 2022;18:1583–1594. doi: 10.2217/fon-2021-1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Efficacy of avapritinib in patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis: hematologic and bone marrow responses from the phase 2 open-label, single-arm, Pathfinder study. George TI, Karner KH, Moser KA, et al. Blood. 2021;138:2565. [Google Scholar]

- 23.n.d n.d. FDA approves avapratinib for advanced systemic mastocytosis. FDA. 2021. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-avapritinib-advanced-systemic-mastocytosis https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-avapritinib-advanced-systemic-mastocytosis