Abstract

Bone-modifying agents (BMA) are extensively used in treating patients with prostate cancer with bone metastases. However, this increases the risk of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ). The safety of long-term BMA administration in clinical practice remains unclear. We aimed to determine the cumulative incidence and risk factors of MRONJ. One hundred and seventy-nine patients with prostate cancer with bone metastases treated with BMA at our institution since 2008 were included in this study. Twenty-seven patients (15%) had MRONJ during the follow-up period (median, 19 months; interquartile range, 9–43 months). The 2-year, 5-year, and 10-year cumulative MRONJ incidence rates were 18%, 27%, and 61%, respectively. Multivariate analysis identified denosumab use as a risk factor for MRONJ, compared with zoledronic acid use (HR 4.64, 95% CI 1.93–11.1). Additionally, BMA use at longer than one-month intervals was associated with a lower risk of MRONJ (HR 0.08, 95% CI 0.01–0.64). Furthermore, six or more bone metastases (HR 3.65, 95% CI 1.13–11.7) and diabetes mellitus (HR 5.07, 95% CI 1.68–15.2) were risk factors for stage 2 or more severe MRONJ. MRONJ should be considered during long-term BMA administration in prostate cancer patients with bone metastases.

Keywords: Denosumab, Jaw, Osteonecrosis, Prostate cancer, Zoledronic acid

Subject terms: Medical research, Risk factors, Urology

Introduction

Almost half the patients with prostate cancer with bone metastases experience skeletal-related events (SREs) within 2 years, and preventing SREs is essential because they significantly reduce the quality of life1. Bone-modifying agents (BMAs), such as zoledronic acid and denosumab, are efficacious in reducing the risk of SREs in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). Therefore, their use is recommended in patients with CRPC with bone metastases2. One of the most crucial adverse events of long-term BMA use is medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ). It was first reported in 20033 and is an intractable disease that negatively affects the quality of life.

More than a decade has passed since the routine use of BMAs began, and the Japanese Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (JAOMS) has reported a significant rise in the incidence of MRONJ in clinical practice, a trend observed globally4. The JAOMS surveys have indicated a concurrent increase in the proportion of severe MRONJ cases5,6. Nashi et al. reported that the incidence of MRONJ is increasing due to prolonged treatment periods, and the number of patients with severe MRONJ of stage 2 or higher is also increasing5. However, the frequency of MRONJ varies considerably. Previous studies have documented an incidence of MRONJ ranging from approximately 0.1 to 32%7–15. Differences in the duration of observation and patient backgrounds may have influenced variations in the incidence of MRONJ. Survival time after BMA use appears to be associated with the incidence of MRONJ 11. However, long-term observational studies are limited.

MRONJ is a multifactorial disease and its etiology is not fully elucidated10. In addition to patient-related factors such as oral hygiene and diabetes, the type of BMA and dosing interval are important factors in the development of MRONJ10,13. A meta-analysis of 6 randomized controlled trials found a significantly higher incidence of MRONJ with denosumab compared to zoledronic acid over 3 years7. Additionally, a meta-analysis of 3 randomized trials indicated a lower incidence of adverse events, including MRONJ, when zoledronic acid was administered every 12 weeks rather than every 4 weeks16. However, the effects of BMA type and dosing interval on MRONJ remain unknown in cases treated with BMA for the long term.

The incidence of MRONJ in patients with prostate cancer (5–39%) has been reported to be higher than in patients with other cancers1,11,17,18. Patients with advanced prostate cancer now achieve prolonged survival owing to novel drugs and treatment modalities19–21. As a result, it is expected that the number of cases of long-term use of BMA would increase. However, the association between prostate cancer and a higher incidence of MRONJ remains unclear, and the risk factors for MRONJ have not been thoroughly discussed. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the cumulative incidence of MRONJ with the long-term use of BMAs in patients with prostate cancer with bone metastasis. We further made the null hypothesis that BMA type and dosing interval do not affect the occurrence of MRONJ. We also evaluate the cumulative incidence of stage 2 or more severe MRONJ and risk factors for MRONJ development.

Materials and methods

Study design and data collection

This was a retrospective, observational study conducted at a single center to determine the cumulative incidence and risk factors for MRONJ in prostate cancer patients with bone metastases who were treated with BMAs.

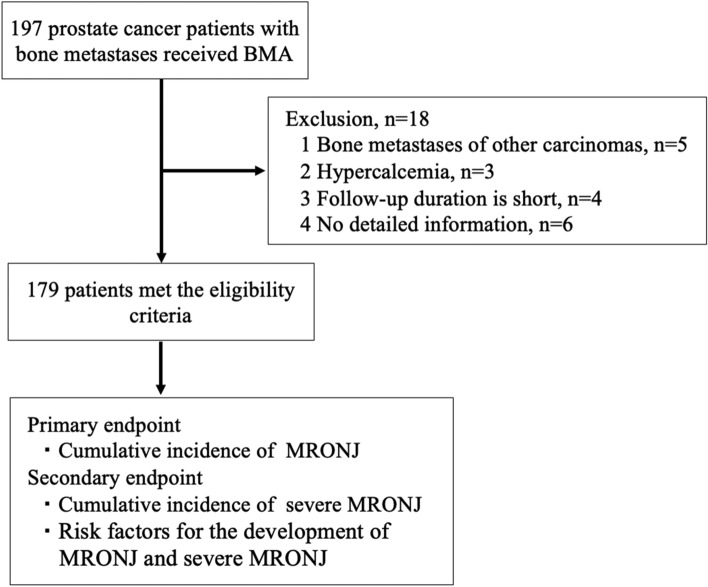

The Department of Urology at our hospital has been using zoledronic acid since January 2008 and denosumab since July 2012 for patients with castration-sensitive or castration-resistant prostate cancer with bone metastases. In Japan, the utilization of zoledronic acid and denosumab for solid tumors with bone metastases is approved by the Japanese Drug Authority. Since July 2012, the attending physicians selected either zoledronic acid or denosumab, depending on the patient's preference and general condition. This study included 197 prostate cancer patients with bone metastases who were treated with BMAs between January 2008 and April 2023. Patients were enrolled at least 2 months after BMA administration. Patients who received BMAs for bone metastases from other carcinomas (n = 5) or for whom BMAs were used to treat hypercalcemia (n = 3) or for whom adequate clinical data were unavailable (n = 6) were excluded from the study. Ultimately, 179 patients met the study eligibility criteria (Fig. 1). Dental evaluation and care were discussed with the primary dentist before the initiation of BMAs. Zoledronic acid was administered intravenously at a dose of 4 mg every four weeks, and the dose was modified according to the manufacturer’s instructions for patients with renal dysfunction. Denosumab was administered subcutaneously at a dose of 120 mg every four weeks. Physicians were allowed to extend the intervals of zoledronic acid and denosumab administration to 6–12 weeks at the start of BMA therapy. In principle, zoledronic acid and denosumab were continued, with discontinuation criteria being the occurrence of MRONJ or deterioration of the patient's Performance Status.

Figure 1.

Study schematic.

Endpoints

The primary and secondary endpoints were the cumulative incidence of MRONJ and the occurrence of severe MRONJ, respectively. The risk factors for the development of MRONJ and severe MRONJ were also examined. When comparing the BMAs for analysis, the first-line BMA received by the patient was selected.

MRONJ was diagnosed by dentists using the diagnostic criteria defined by the Japanese Allied Committee on Osteonecrosis of the jaw. The diagnosis was based on current or previous treatment with bisphosphonates or denosumab, the presence of exposed necrotic bone in the maxillofacial region lasting > 8 weeks, and no history of radiation therapy to the jawbone. The stage of MRONJ was indicated according to the 2017 Japanese Position Paper22, depending on the severity of symptoms. In this study, we defined severe MRONJ as MRONJ of stages 2 and 3.

We conducted analyses using data extracted from medical records to investigate the risk factors associated with MRONJ. The clinical parameters examined included: age, body mass index (BMI), type and duration of BMA treatment, BMA administration interval, prostate cancer type (castration-sensitive prostate cancer [CSPC] or CRPC), number of bone metastases at BMA initiation (extent of disease [EOD] grade23), presence of diabetes, medications (steroids and anticoagulants), and clinical laboratory data at BMA initiation (serum prostate-specific antigen [PSA], serum alkaline phosphatase [ALP], serum lactate dehydrogenase [LDH], serum calcium [Ca], serum albumin [Alb], hemoglobin [Hb], serum tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase-5b [TRACP-5b], serum bone-specific alkaline phosphatase [BAP], and serum pyridinoline cross-linked carboxyterminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen [ICTP] levels).

Statistical analysis

The cumulative incidence of MRONJ was calculated using Kaplan–Meier analysis. Risk factors for MRONJ were analyzed by Cox regression analysis using JMP software (JMP version 17.0.0; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Osaka University (ethics review number: 13397-20). An opt-out consent procedure was employed for the use of patient data obtained in routine medical care. The informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the initiation of BMA administration. The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Results

Patient characteristics

The patient characteristics (n = 179) are summarized in Table 1. A total of 109 patients received zoledronic acid, and 70 patients received denosumab. Four patients who switched from zoledronic acid to denosumab during the study period were included in the zoledronic acid group: zoledronic acid duration (9, 17, 36, 36 months) and subsequent denosumab duration (37, 4, 4, 10 months). The median age of the patients was 72 years (interquartile range [IQR] 67–78), and the median observation period was 19 months (IQR 9–43 months). The treatment duration was longer, and the ALP, LDH, and BAP levels were higher at BMA induction in the zoledronic acid group than in the denosumab group. The Ca level at BMA induction was higher in the denosumab group than in the zoledronic acid group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient’s characteristics at BMA induction.

| Total | Zoledronic acid | Denosumab | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 179 | N = 109 (61%) | N = 70 (39%) | ||

| Median age, years (IQR) | 72 (67–78) | 71 (65–78) | 73 (68–77) | 0.606 |

| Median BMI, kg/m2 (IQR) | 22.0 (19.5–24.4) | 22.0 (20.0–24.9) | 22.1 (18.6–24.2) | 0.179 |

| Median duration of BMA treatment, months (IQR) | 13 (7–28) | 17 (9–47) | 10 (5–22) | 0.002 |

| Median duration of ADT before BMA, months (IQR) | 20 (2–54) | 15 (1–50) | 23 (3–56) | 0.099 |

| Median number BMA doses | 11 (5–26) | 15 (7–36) | 9 (4–15) | < 0.001 |

| Castration sensitivity, N (%) | ||||

| CSPC | 72 (40%) | 47 (43%) | 25 (36%) | 0.873 |

| CRPC | 107 (60%) | 62 (57%) | 45 (64%) | 0.203 |

| BMA agent, N (%) | ||||

| Zoledronic acid | 109 (61%) | |||

| Denosumab | 70 (39%) | |||

| EOD grade at BMA induction, N (%) | ||||

| 0 | 4 (2%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | |

| 1 | 64 (36%) | 42 (39%) | 22 (32%) | |

| 2 | 55 (31%) | 32 (29%) | 23 (33%) | |

| 3 | 38 (21%) | 22 (20%) | 16 (23%) | |

| 4 | 16 (9%) | 9 (8%) | 7 (10%) | |

| Unknown | 2 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Dosing interval of BMA | ||||

| 1 month | 155 (87%) | 97 (89%) | 58 (83%) | 0.244 |

| > 1 month | 24 (13%) | 12 (11%) | 12(17%) | 0.239 |

| Blood test results at BMA induction | ||||

| Median serum PSA, ng/ml (IQR) | 25.9 (4.0–155) | 38.2 (4.8–204.2) | 15.2 (3.1–115.7) | 0.21 |

| Median serum ALP, U/l (IQR) | 280 (182–502) | 328 (222–581) | 196 (112–400) | < 0.001 |

| Median serum LDH, U/l (IQR) | 200 (176–243) | 207 (183–254) | 190 (169–230) | 0.003 |

| Median serum Ca, mg/dl (IQR) | 9.0 (8.7–9.4) | 8.9 (8.5–9.2) | 9.3 (8.9–9.6) | < 0.001 |

| Median serum Alb, g/dl (IQR) | 3.9 (3.5–4.1) | 3.8 (3.4–4.2) | 3.9 (3.6–4.1) | 0.327 |

| Median serum Hb, g/dl (IQR) | 12.2 (11.0–13.2) | 12.2 (11.0–13.3) | 12.2 (10.9–3.1) | 0.533 |

| Median serum TRACP-5b, mU/dl (IQR) | 541 (377–1027) | 569 (401–1055) | 395 (315–960) | 0.204 |

| Median serum BAP, μg/l (IQR) | 19.8 (12.9–39) | 24.1 (14.1–44.6) | 14.6(11.8–21.9) | 0.016 |

| Median serum ICTP, ng/ml (IQR) | 6.3 (4.2–11.7) | 6.4 (4.2–11.4) | 5.8 (4.0–12.2) | 0.932 |

| Corticosteroid usage, N (%) | 82 (45%) | 52 (47%) | 30 (42%) | 0.542 |

| Diabetes mellitus, N (%) | 34 (19%) | 21 (19%) | 13 (18%) | 0.858 |

| Anticoagulant usage, N (%) | 42 (23%) | 25 (23%) | 17 (24%) | 0.908 |

BMA bone-modifying agent; BMI body mass index; ADT androgen-deprivation therapy; CSPC castration-sensitive prostate cancer; CRPC castration-resistant prostate cancer; EOD extent of disease; PSA prostate-specific antigen; ALP alkaline phosphatase; LDH lactate dehydrogenase; Ca calcium; Alb albumin; Hb hemoglobin; TRACP-5b tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase-5b; BAP bone-specific alkaline phosphatase; ICTP pyridinoline cross-linked carboxy-terminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen.

Cumulative incidence of MRONJ

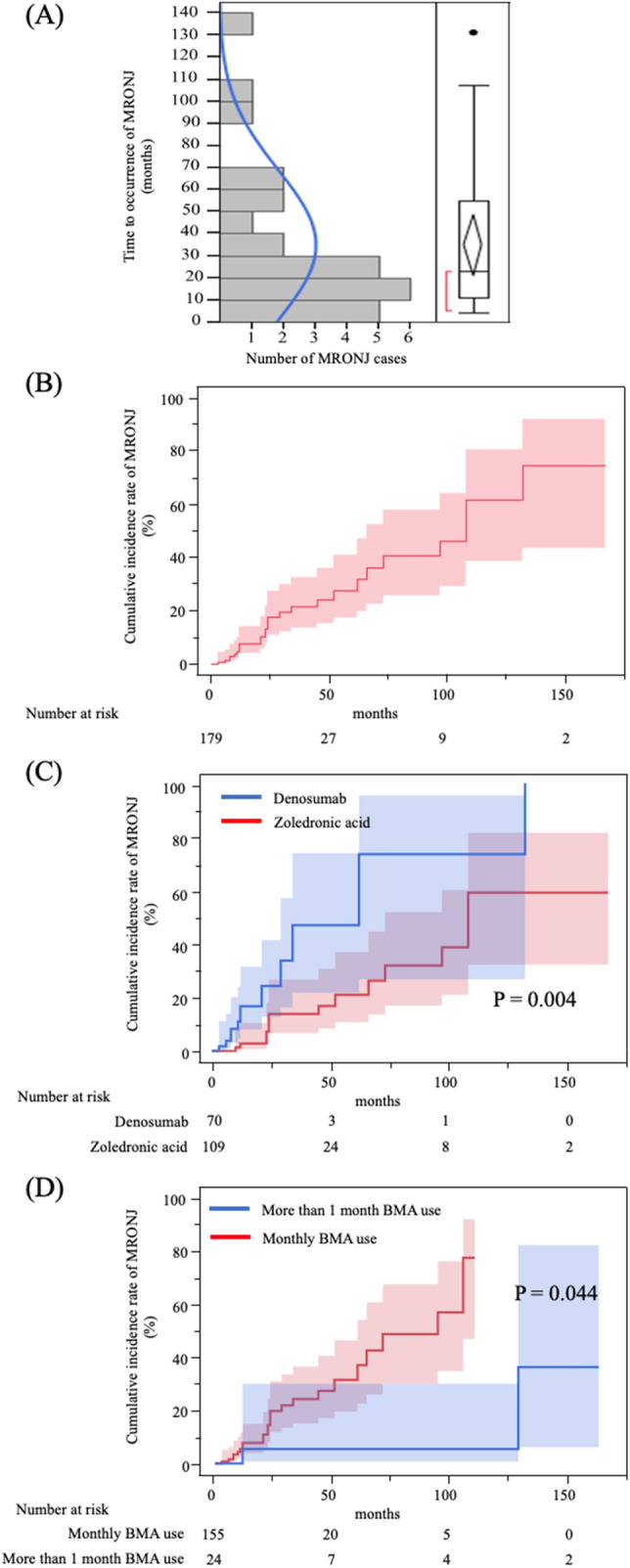

MRONJ was diagnosed in 27 of 179 patients (15%) during the observation period, in 14 of 109 patients (13%) in the zoledronic acid group and 13 out of 70 patients (19%) in the denosumab group. The median duration of BMAs treatment before the onset of MRONJ was 23 months for all cohorts, with 25 and 13 months in the zoledronic acid and denosumab groups, respectively (Table 2). The MRONJ stages at diagnosis were 0 (15%), 1 (19%), 2 (44%), and 3 (22%) (Table 2). The time to occurrence of MRONJ was not normally distributed, with the majority of cases occurring within the first 3 years of treatment, although occurrences were also observed after long-term treatment (Fig. 2A). The cumulative incidence rates of MRONJ of any stage were 8%, 18%, 27%, and 61% at 1, 2, 5, and 10 years, respectively (Fig. 2B).

Table 2.

Cumulative incidence of MRONJ.

| Total | Zoledronic acid | Denosumab | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 179 | N = 109 | N = 70 | |

| Characteristics of MRONJ | |||

| Number of MRONJ cases (%) | 27/179 (15%) | 14/109 (13%) | 13/70 (19%) |

| Median time to MRONJ, months (range) | 23 (4–131) | 25 (10–107) | 13 (4–131) |

| MRONJ stage, N (%) | |||

| 0 | 4 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (31%) |

| 1 | 5 (19%) | 3 (22%) | 2 (15%) |

| 2 | 12 (44%) | 9 (64%) | 3 (23%) |

| 3 | 6 (22%) | 2 (14%) | 4 (31%) |

MRONJ medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence rate of any stage of MRONJ. (A) While the majority of cases of MRONJ occurred within three years, there were also several instances of MRONJ occurring during long-term treatment. (B) The 2-year, 5-year, and 10-year cumulative incidence rates of MRONJ were 18%, 27%, and 61%, respectively. (C) In the patients receiving zoledronic acid or denosumab, denosumab use rather than zoledronic acid use was a significant risk factor for the development of MRONJ (p = 0.004). (D) In the patients with monthly BMA use or BMA use at longer than one-month intervals, BMA administration at longer than one-month intervals was associated with a lower risk of MRONJ than monthly BMA use (p = 0.044). MRONJ medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Risk factors for the development of MRONJ of any stage

Table 3 presents the results of the analysis of factors associated with the development of MRONJ of any stage. In the univariate analysis, denosumab use rather than zoledronic acid use was a significant risk factor for the development of MRONJ (HR 3.26, 95% CI 1.46–7.24, p = 0.004). BMA administration at intervals longer than one month was associated with a lower risk of MRONJ than monthly BMA use (HR 0.13, 95% CI 0.02–0.95, p = 0.044). In the multivariate analysis, denosumab use was a significant predictor of MRONJ (HR 4.64, 95% CI 1.93–11.1, p < 0.001). In addition, BMA administration at longer than one-month intervals was associated with a lower risk of MRONJ (HR 0.08, 95% CI 0.01–0.64, p = 0.017). Kaplan–Meier curves are developed for the denosumab and zoledronic acid groups as well as for the monthly BMA and BMA administration at longer than one-month intervals groups (Figs. 2C,D).

Table 3.

Risk factors for any stage of MRONJ (univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard analyses).

| Univariate analysis (N = 179) | Multivariate analysis (N = 179) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p value | RR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Age | ||||||

| ≧ 70 vs. < 70 | 1.3 | 0.59–2.84 | 0.507 | |||

| BMI | ||||||

| ≧ 25 vs. < 25 | 1.97 | 0.85–4.58 | 0.13 | |||

| BMA | ||||||

| Denosumab vs. zoledronic acid | 3.26 | 1.46–7.24 | 0.004 | 4.64 | 1.93–11.1 | < 0.001 |

| Castration sensitivity | ||||||

| CRPC vs. CSPC | 1.45 | 0.67–3.15 | 0.338 | |||

| T ≧ 3 vs. ≦ 2 | 1.61 | 0.66–3.89 | 0.272 | |||

| N ≧ 1 vs. 0 | 1.38 | 0.56–3.38 | 0.477 | |||

| M 1 vs. 0 | 1.98 | 0.74–5.23 | 0.141 | |||

| Gleason score 9 ≧ vs. ≦ 8 | 1.25 | 0.42–3.69 | 0.666 | |||

| Duration of ADT before BMA (months) | ||||||

| ≧ 20 vs. < 20 | 1.07 | 0.49–2.33 | 0.854 | |||

| Interval of BMA (months) | ||||||

| > 1 vs. 1 | 0.13 | 0.02–0.95 | 0.044 | 0.08 | 0.01–0.64 | 0.017 |

| EOD grade at BMA induction | ||||||

| ≧ 2 vs. < 2 | 2.18 | 0.91–5.20 | 0.078 | |||

| Use of steroid | ||||||

| Yes vs. No | 0.94 | 0.40–2.21 | 0.895 | |||

| Use of anticoagulant | ||||||

| Yes vs. No | 1.06 | 0.42–2.65 | 0.892 | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.87 | 0.77–4.52 | 0.165 | |||

| PSA at BMA induction (ng/ml) | ||||||

| ≧ 25.0 vs. < 25.0 | 0.93 | 0.41–2.09 | 0.869 | |||

| ALP at BMA induction (U/l) | ||||||

| ≧ 260 vs. < 260 | 1.08 | 0.50–2.33 | 0.839 | |||

| LDH at BMA induction (U/l) | ||||||

| ≧ 220 vs. < 220 | 0.88 | 0.36–2.11 | 0.784 | |||

| Ca at BMA induction (mg/dl) | ||||||

| ≧ 9.0 vs. < 9.0 | 2.17 | 0.93–5.07 | 0.073 | |||

| Alb at BMA induction (g/dl) | ||||||

| ≧ 4.0 vs. < 4.0 | 1.23 | 0.532.81 | 0.624 | |||

| Hb at BMA induction (g/dl) | ||||||

| ≧ 12.2 vs. < 12.2 | 1.23 | 0.56–2.73 | 0.595 | |||

| TRACP-5b at BMA induction (mU/dl) | ||||||

| ≧ 590 vs. < 590 | 5.01 | 0.58–43.0 | 0.142 | |||

| BAP at BMA induction (μg/l) | ||||||

| ≧ 20 vs. < 20 | 1.08 | 0.31–3.77 | 0.895 | |||

| ICTP at BMA induction (ng/ml) | ||||||

| ≧ 5.24 vs. < 5.24 | 0.36 | 0.07–1.83 | 0.22 | |||

MRONJ medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw; BMI body mass index; BMA bone-modifying agent; CRPC castration-resistant prostate cancer; CSPC castration-sensitive prostate cancer; ADT androgen-deprivation therapy; EOD extent of disease; PSA prostate-specific antigen; ALP alkaline phosphatase; LDH lactate dehydrogenase; Ca calcium; Alb albumin; Hb hemoglobin; TRACP-5b tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase-5b; BAP bone specific alkaline phosphatase; ICTP pyridinoline cross-linked carboxyterminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen.

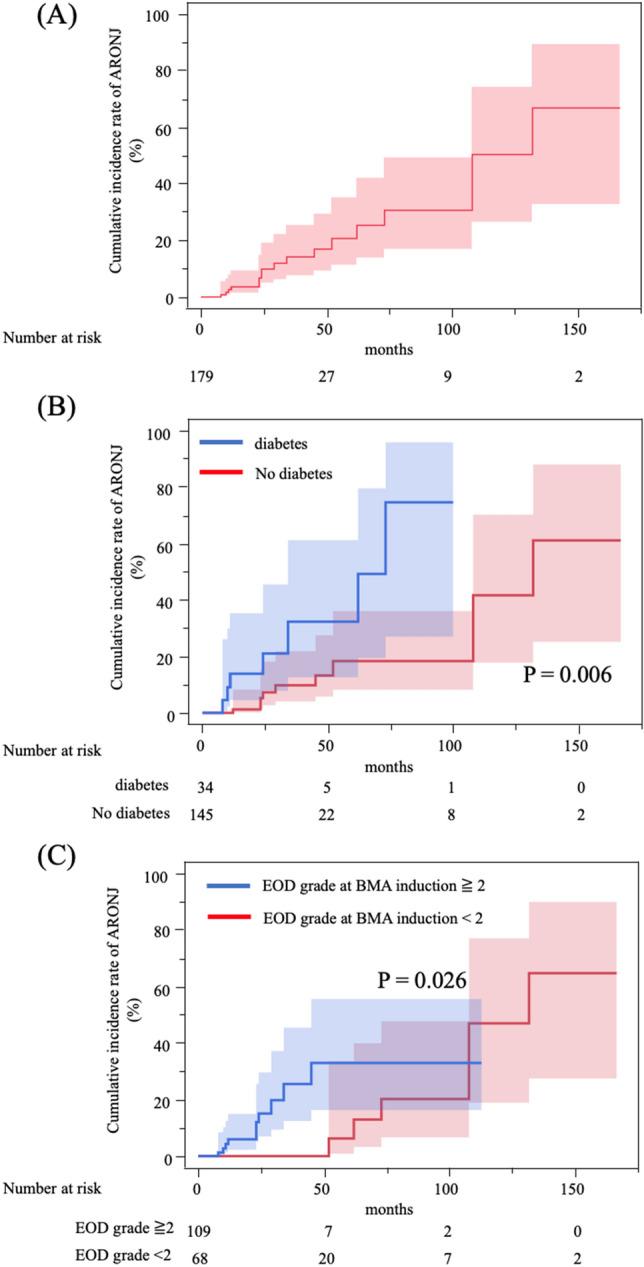

Cumulative incidence and risk factors for severe MRONJ

The cumulative incidence rates of severe MRONJ were 3%, 7%, 21%, and 51% at 1, 2, 5, and 10 years, respectively (Fig. 3A). Additionally, Table 4 outlines the results of analyzing the factors associated with severe MRONJ of stage 2 or higher. In the univariate analysis, an EOD grade of 2 or higher at BMA induction (six or more bone metastases) compared to an EOD grade of 0 or 1 (HR 3.73, 95% CI 1.16–11.9, p = 0.026) and the presence of diabetes mellitus (HR 4.38, 95% CI 1.53–12.5, p = 0.006) were the significant risk factors for the occurrence of severe MRONJ. In the multivariate analysis, an EOD grade of 2 or higher at BMA induction (HR 3.65, 95% CI 1.13–11.7, p = 0.030) and the presence of diabetes mellitus (HR 5.07, 95% CI 1.68–15.2, p = 0.004) were the significant predictors of severe MRONJ (Fig. 3B,C).

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence rate of severe MRONJ. (A) The 2-year, 5-year, and 10-year cumulative incidence rates of severe MRONJ were 7%, 21%, and 51%, respectively. (B) Among patients with or without diabetes, the incidence rate of severe MRONJ was significantly different between patients with diabetes and those without diabetes (p = 0.006). (C) Among patients with EOD grade at BMA induction ≧2 or EOD grade at BMA induction < 2, the incidence rate of MRONJ was significantly different between the patients with EOD grade ≧2 and those with EOD grade < 2 (p = 0.026). MRONJ medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw; EOD extent of the disease.

Table 4.

Risk factors for severe MRONJ (univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard analyses).

| Univariate analysis (N = 179) | Multivariate analysis (N = 179) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p value | RR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Age | ||||||

| ≧ 70 vs. < 70 | 1.1 | 0.41–2.90 | 0.846 | |||

| BMI | ||||||

| ≧ 25 vs. < 25 | 1.52 | 0.48–4.77 | 0.47 | |||

| BMA | ||||||

| Denosumab vs. zoledronic acid | 2.06 | 0.73–5.84 | 0.172 | |||

| Castration sensitivity | ||||||

| CRPC vs. CSPC | 1.43 | 0.54–3.76 | 0.468 | |||

| T ≧ 3 vs. ≦ 2 | 2.09 | 0.67–6.53 | 0.202 | |||

| N ≧ 1 vs. 0 | 1.06 | 0.32–3.48 | 0.92 | |||

| M 1 vs. 0 | 2.13 | 0.61–7.43 | 0.235 | |||

| Gleason score 9≧ vs. ≦8 | 1.07 | 0.30–3.80 | 0.915 | |||

| Duration of ADT before BMA (months) | ||||||

| ≧ 20 vs. < 20 | 0.73 | 0.26–2.04 | 0.56 | |||

| Dosing interval of BMA (months) | ||||||

| > 1 vs. 1 | 2.23 × 10–9 | 0–NA | 0.999 | |||

| EOD grade at BMA induction | ||||||

| ≧ 2 vs. < 2 | 3.73 | 1.16–11.9 | 0.026 | 3.65 | 1.13–11.7 | 0.03 |

| Use of steroid | ||||||

| Yes vs. No | 0.529 | 0.14–1.88 | 0.895 | |||

| Use of anticoagulant | ||||||

| Yes vs. No | 1.58 | 0.55–4.54 | 0.391 | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 4.38 | 1.53–12.5 | 0.006 | 5.07 | 1.68–15.2 | 0.004 |

| PSA at BMA induction (ng/ml) | ||||||

| ≧ 25.0 vs. < 25.0 | 1.27 | 0.46–3.51 | 0.641 | |||

| ALP at BMA induction (U/l) | ||||||

| ≧ 260 vs. < 260 | 0.76 | 0.28–2.00 | 0.58 | |||

| LDH at BMA induction (U/l) | ||||||

| ≧ 220 vs. < 220 | 0.78 | 0.24–2.44 | 0.67 | |||

| Ca at BMA induction (mg/dl) | ||||||

| ≧ 9.0 vs. < 9.0 | 1.33 | 0.48–3.66 | 0.578 | |||

| Alb at BMA induction (g/dl) | ||||||

| ≧ 4.0 vs. < 4.0 | 1.36 | 0.48–3.80 | 0.554 | |||

| Hb at BMA induction (g/dl) | ||||||

| ≧ 12.2 vs. < 12.2 | 1.04 | 0.39–2.77 | 0.935 | |||

| TRACP-5b at BMA induction (mU/dl) | ||||||

| ≧ 590 vs. < 590 | 4 | 0.44–36.0 | 0.215 | |||

| BAP at BMA induction (µg/l) | ||||||

| ≧ 20 vs. < 20 | 1.47 | 0.32–6.59 | 0.614 | |||

| ICTP at BMA induction (ng/ml) | ||||||

| ≧ 5.24 vs. < 5.24 | 0.747 | 0.12–4.62 | 0.755 | |||

MRONJ medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw; BMI body mass index; BMA bone-modifying agents; CRPC castration-resistant prostate cancer; CSPC castration-sensitive prostate cancer; ADT androgen-deprivation therapy; EOD extent of disease; PSA prostate-specific antigen; ALP alkaline phosphatase; LDH lactate dehydrogenase; Ca calcium; Alb albumin; Hb hemoglobin; TRACP-5b tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase-5b; BAP bone specific alkaline phosphatase; ICTP pyridinoline cross-linked carboxyterminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen.

Discussion

This study focused on the cumulative incidence of MRONJ with long-term BMA use in prostate cancer patients with bone metastases. The cumulative incidence of MRONJ was approximately one-quarter at 5 years, but at 10 years, more than half of the patients had developed the disease. Denosumab use was the risk factor for MRONJ of any stage, whereas BMA administration at longer than one-month intervals was associated with a lower risk of MRONJ. Thus, the null hypothesis that BMA type and dosing interval do not affect the occurrence of MRONJ has been rejected. The study also found that the presence of diabetes and an EOD grade of 2 or higher at BMA induction were risk factors for severe MRONJ.

Recently, Nakai et al.1 reported an MRONJ incidence rate of 27.5% in patients with prostate cancer and bone metastases at 5 years, which is similar to our findings. However, the incidence at 10 years remained unknown. In this study, the 10-year cumulative incidence of MRONJ was 61%. Although the majority of MRONJ cases occurred within the first 3 years, some MRONJ cases were observed even after long-term treatment. This highlights the substantial risk associated with long-term BMA use. The association between prolonged BMA use and an increased incidence of MRONJ has been increasingly reported10,11,24,25, making the optimal duration of BMA administration a crucial issue for the future, especially in patients with prostate cancer who undergo prolonged BMA therapy.

Currently, 3–4-weekly zoledronic acid administration or 4-weekly denosumab administration is recommended to reduce the incidence of SREs in patients with CRPC with bone metastases. However, the optimal dosing intervals remain unclear. A systematic review of three randomized trials revealed a decreased occurrence of MRONJ, with zoledronic acid administered every 12 weeks compared to every 4 weeks16. In breast cancer, dosing intervals of zoledronic acid every 3–4 weeks and every 12 weeks are both recommended as first choices26. In prostate cancer, zoledronic acid and denosumab are recommended every 4 weeks according to the ASCO-CCO and ESMO guidelines27,28. However, given the increased incidence of MRONJ with prolonged administration of BMA, extending the dosing interval is an issue that should be considered. To date, there are no established views on extended BMA dosing intervals in prostate cancer. At our hospital, the dosing interval is currently extended based on the judgment of the clinician. This study found that patients with BMA administration intervals longer than one month had a lower risk of any stage of MRONJ than those that were administered BMAs every 4 weeks. Among patients who received BMA at intervals of longer than one month at the start of therapy, severe cases of MRONJ were rare (only one case). In patients who have been using BMAs for a long time, a decrease in the cumulative dose owing to longer dosing intervals may reduce the risk of developing MRONJ.

Although denosumab is more effective than zoledronic acid in reducing the incidence of SREs, an analysis of eight RCTs found a significantly higher incidence of MRONJ with denosumab than with zoledronic acid administration7. The incidence of MRONJ with denosumab use ranged from 0.5–2.1% at 1 year, 1.1–3.0% at 2 years, and 1.3–3.2% at 3 years7. Long-term denosumab use has been associated with an increased risk of MRONJ; however, observational studies on denosumab treatment beyond 3 years are limited. Our study identified denosumab use as an independent risk factor for MRONJ development compared with zoledronic acid use, even during long-term follow-up. The use of denosumab is expected to increase in the future because of its potential to mitigate nephrotoxicity and its non-requirement for intravenous infusion. The different degrees of osteoclast activity inhibition by zoledronic acid and denosumab may account for the differences in the incidence of MRONJ. In this study, there was a higher proportion of MRONJ stage 0 cases in the denosumab group. This could suggest that varying degrees of osteoclast inhibition led to an increase in non-exposed lesions, which do not exhibit bone exposure but show imaging evidence of bone resorption or osteonecrosis. However, the mechanisms underlying the increased risk of MRONJ associated with denosumab use remain unclear. When considering long-term BMA administration, it may be better to select zoledronic acid or increase the dosing interval for denosumab. A clinical trial investigating the incidence of MRONJ with 4-weekly denosumab administration versus 12-weekly administration is ongoing (NCT02051218), and its findings are eagerly anticipated.

This study revealed a 7% incidence of severe MRONJ at the 2-year mark, which escalated to a significant 51% cumulative incidence over 10 years. The American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) recently announced that the cumulative BMA dose was unrelated to severity, which differs from previous observations29. Reports of a higher incidence of severe MRONJ in patients receiving long-term zoledronic acid administration are consistent with the findings of the present study5. Depending on the disease stage, conservative or surgical therapy is recommended for MRONJ29,30. Many studies have reported better efficacy and outcomes in patients undergoing surgical therapy than in those who do not31,32, leading to a trend toward recommending surgical therapy. Palla et al. stated that early surgery has a higher cure rate, is less invasive, and is associated with a better quality of life than advanced-stage surgery33. Therefore, diagnosing MRONJ at an early stage is crucial.

Although the pathogenesis of MRONJ is not fully understood, it is believed to be related to the presence of numerous bacteria in the oral cavity and specific characteristics of the jawbone. Inflammation easily spreads to the jawbone because of tooth infection, and the jawbone is situated in an infection-prone area34. Furthermore, BMA administration, with its resultant bone remodeling inhibition, suppression of osteoclast activity, and angiogenesis inhibition combined with the abundance of oral bacteria and easily infected jawbones, is hypothesized to cause MRONJ22,35. Nashi et al. reported that age and low serum albumin levels were associated with severe MRONJ, reflecting delayed wound healing36. The carcinomatous state with a high number of bone metastases is a systemic inflammatory state in which inflammation delays wound healing and increases scar formation37. In this study, we found that the presence of numerous bone metastases with an EOD of grade 2 or higher at BMA induction was a risk factor for severe MRONJ. These results support the finding that MRONJ results from local inflammation that is associated with jawbone infection38 and becomes more severe due to delayed wound healing. In this study, diabetes was identified as a risk factor for severe MRONJ. Diabetes has been reported to be associated with delayed wound healing37, and obesity has been associated with an increased number of oral microorganisms, contributing to periodontal disease37,38 and poor oral hygiene39,40. These reports are consistent with our observation that diabetes is a risk factor for severe MRONJ.

This study had several limitations. Firstly, this was a single-center, retrospective, observational study with a relatively small number of patients who developed MRONJ, resulting in limited findings. Secondly, data on the outcomes of patients who developed MRONJ were lacking, making it unclear whether the disease improved, remained stable, or worsened. Thirdly, the MRONJ diagnoses were not made by a single dentist, introducing potential variability in the diagnostic process. Fourth, the assessment of MRONJ relied solely on AAOMS staging. Clinical symptoms such as pain and signs of infection, along with radiographical evaluation, were utilized to evaluate the disease, but some variability may exist.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study revealed a significantly increased cumulative incidence of MRONJ in patients with prostate cancer and bone metastases after long-term BMA treatment.

Denosumab use was identified as an independent risk factor for MRONJ, and BMA use at intervals longer than one month was associated with a lower risk of MRONJ. Diabetes mellitus and numerous bone metastases were also identified as risk factors for severe MRONJ. These findings advocate for considering extended BMA dosing intervals in patients with prostate cancer with bone metastases undergoing long-term therapy. Furthermore, the recognition of risk factors for severe MRONJ underscores the importance of early detection in patients with diabetes mellitus and multiple bone metastases as a preventive measure.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (http://www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Author contributions

M.T. and K.H. contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection and analysis were performed by M.T., K.H., A.Y., Y.H., Y.L., N.S., T.O., Y.O., A.Y., T.U., G.Y., Y.I., Y.Y., T.K., A.K., and N.N. Data analysis was performed by M.T., Y.L., T.O. and K.H. The original draft of the manuscript was written by M.T. All authors contributed to review, editing and final approval of manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI [grant number 22K09447].

Data availability

Raw data were generated at Osaka University. Derived data supporting the results of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nakai Y, Kanaki T, Yamamoto A, et al. Antiresorptive agent-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in prostate cancer patients with bone metastasis treated with bone-modifying agents. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2021;39:295–301. doi: 10.1007/s00774-020-01151-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2019) NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology prostate cancer version 4.

- 3.Marx R. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: A growing epidemic. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003;61:1115–1117. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(03)00720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kishimoto H, Kurita H. The number of patients with bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws still increases significantly in Japan e based on the data from annual survey of the oral diseases by JAOMS. Jpn J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022;68:161–163. doi: 10.5794/jjoms.68.161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nashi M, Kishimoto H, Kobayashi M, et al. Incidence of antiresorptive agent-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A multicenter retrospective epidemiological study in Hyogo Prefecture, Japan. J. Dent. Sci. 2023;18:1156–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2022.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kishimoto H, Noguchi K, Takaoka K. Novel insight into the management of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) Jpn Dent. Sci. Rev. 2019;55:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jdsr.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Limones A, Sáez-Alcaide LM, Díaz-Parreño SA, et al. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (MRONJ) in cancer patients treated with denosumab vs zoledronic acid: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2020;25:e326–e336. doi: 10.4317/medoral.23324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colella G, Campisi G, Fusco V, et al. American association of oral and maxillofacial surgeons position paper: Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the Jaws-2009 update: The need to refine the BRONJ definition. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Med. Pathol. 2009;67:2698–2699. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hellstein W, Adler A, Edwards B, et al. Managing the care of patients receiving antiresorptive therapy for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis: Executive summary of recommendations from the American dental association council on scientific affairs. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2011;142:1243–1251. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2011.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bedogni A, Mauceri R, Campisi G, et al. Italian position paper (SIPMO-SICMF) on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) Oral Dis. 2024;00:1–31. doi: 10.1111/odi.14887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hata H, Imamachi K, Kitagawa Y, et al. Prognosis by cancer type and incidence of zoledronic acid–related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A single-center retrospective study. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:4505–4514. doi: 10.1007/s00520-022-06839-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu PA, Shen CY, Chung WP, et al. Long-term use of denosumab and its association with skeletal-related events and osteonecrosis of the jaw. Sci. Rep. 2023;13:8403. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-35308-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikesue H, Mouri M, Hashida T, et al. Associated characteristics and treatment outcomes of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients receiving denosumab or zoledronic acid for bone metastases. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:4763–4772. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06018-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehrenstein V, Jørgensen UH, Sørensen HT, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw among patients with cancer treated with denosumab or zoledronic acid : Results of a regulator-mandated cohort postauthorization safety study in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Cancer. 2021;127:4050–4058. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ueda N, Aoki K, Kurita T, et al. Oral risk factors associated with medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with cancer. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2021;39:623–630. doi: 10.1007/s00774-020-01195-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santini D, Galvano A, Pantano F, et al. How do skeletal morbidity rate and special toxicities affect 12-week versus 4-week schedule zoledronic acid efficacy? A systematic review and a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2019;142:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanno C, Kojima M, Tezuka Y, et al. Antiresorptive agent-related osteonecrosis of the jaw risk in cancer patients before bone-modifying agent therapy: A retrospective study of 511 patients. Bone. 2023;177:116892. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2023.116892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith M, Saad F, Coleman R, et al. Denosumab and bone-metastasis-free survival in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: Results of a phase 3, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:39–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61226-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatano K, Nonomura N. Systemic therapies for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: An updated review. World J. Mens Health. 2023;41:769–784. doi: 10.5534/wjmh.220200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oka T, Hatano K, Okuda Y, et al. The presence of lymph node metastases and time to castration resistance predict the therapeutic effect of enzalutamide for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023;28:427–435. doi: 10.1007/s10147-022-02288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hatano K, Nishimura K, Nakai Y, et al. Weekly low-dose docetaxel combined with estramustine and dexamethasone for Japanese patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013;18:704–710. doi: 10.1007/s10147-012-0429-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoneda T, Hagino H, Sugimoto T, et al. Antiresorptive agent-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: Position paper 2017 of the Japanese allied committee on osteonecrosis of the jaw. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2017;35:6–19. doi: 10.1007/s00774-016-0810-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soloway MS, Hardeman SW, Moinuddin M, et al. Stratification of patients with metastatic prostate cancer based on extent of disease on initial bone scan. Cancer. 1988;61:195–202. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880101)61:1<195::AID-CNCR2820610133>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bamias A, Kastritis E, Bamia C, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer after treatment with bisphosphonates: incidence and risk factors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:8580–8587. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Badros A, Weikel D, Salama A, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in multiple myeloma patients: Clinical features and risk factors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24:945–952. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Poznak C, Somerfield MR, Barlow WE, et al. Role of bone-modifying agents in metastatic breast cancer: An American society of clinical oncology-cancer care Ontario focused guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35:3978–3986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.4614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saylor PJ, Rumble RB, Michalski JM, et al. Bone health and bone-targeted therapies for prostate cancer: ASCO endorsement of a cancer care Ontario guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020;38:1736–1743. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coleman R, Hadji P, Jordan K, et al. Bone health in cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines. Ann. Oncol. 2020;31:1650–1663. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Aghaloo T, et al. American association of oral and maxillofacial surgeons’ position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws-2022 update. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022;80:920–943. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2022.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yarom CL, Shapiro D, Peterson C, et al. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: MASCC/ISOO/ASCO clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019;37:2270–2290. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayashida S, Soutome S, Yanamoto S, et al. Evaluation of the treatment strategies for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (MRONJ) and the factors affecting treatment outcome: A multicenter retrospective study with propensity score matching analysis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2017;32:2022–2029. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giudice A, Barone S, Diodati F, et al. Can surgical management improve resolution of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw at early stages? A prospective cohort study. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020;78:1986–1999. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2020.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palla B, Burian E, Deek A, et al. Comparing the surgical response of bisphosphonate-related versus denosumab-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021;79:1045–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2020.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shibahara T. Antiresorptive agent-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (ARONJ): A twist of fate in the bone. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2019;247:75–86. doi: 10.1620/tjem.247.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saad F, Brown J, Van Poznak C, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of osteonecrosis of the jaw: Integrated analysis from three blinded active-controlled phase III trials in cancer patients with bone metastases. Ann. Oncol. 2012;23:1341–1347. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nashi M, Hirai T, Iwamoto T, et al. Clinical risk factors for severity and prognosis of antiresorptive agent-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A retrospective observational study. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2022;40:1014–1020. doi: 10.1007/s00774-022-01367-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sabine AE, Thomas K, Jefferey MD. Inflammation in wound repair: Molecular and cellular mechanisms. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2007;127:514–525. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shin W, Kim C. Prognostic factors for outcome of surgical treatment in medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018;44:174–181. doi: 10.5125/jkaoms.2018.44.4.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsushita K, Hamaguchi M, Hashimoto M, et al. The novel association between red complex of oral microbe and body mass index in healthy Japanese: A population based cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2015;57:135–139. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.15-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adachi N, Kobayashi Y. One-year follow-up study on associations between dental caries, periodontitis, and metabolic syndrome. J. Oral Sci. 2020;62:52–56. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.18-0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data were generated at Osaka University. Derived data supporting the results of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.