Abstract

Immunosuppression induced by measles virus (MV) is associated with unresponsiveness of peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) to mitogenic stimulation ex vivo and in vitro. In mixed lymphocyte cultures and in an experimental animal model, the expression of the MV glycoproteins on the surface of UV-inactivated MV particles, MV-infected cells, or cells transfected to coexpress the MV fusion (F) and the hemagglutinin (H) proteins was found to be necessary and sufficient for this phenomenon. We now show that MV fusion-inhibitory peptides do not interfere with the induction of immunosuppression in vitro, indicating that MV F-H-mediated fusion is essentially not involved in this process. Proteolytic cleavage of MV F0 protein by cellular proteases, such as furin, into the F1-F2 subunits is, however, an absolute requirement, since (i) the inhibitory activity of MV-infected BJAB cells was significantly impaired in the presence of a furin-inhibitory peptide and (ii) cells expressing or viruses containing uncleaved F0 proteins revealed a strongly reduced inhibitory activity which was improved following trypsin treatment. The low inhibitory activity of effector structures containing mainly F0 proteins was not due to an impaired F0-H interaction, since both surface expression and cocapping efficiencies were similar to those found with the authentic MV F and H proteins. These results indicate that the fusogenic activity of the MV F-H complexes can be uncoupled from their immunosuppressive activity and that the immunosuppressive domains of these proteins are exposed only after proteolytic activation of the MV F0 protein.

A virus-induced transient suppression of immune functions is the major cause of the high morbidity and mortality rates associated with acute measles worldwide (reviewed in reference 10). The immunosuppression induced by measles virus (MV) is characterized by the loss of delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions, a high sensitivity to opportunistic infections, and the reactivation of persistent infections. A marked leukopenia affecting both T and B cells is characteristically accompanied by strongly impaired proliferative responses of isolated peripheral blood cells toward mitogenic, allogenic, and recall antigen stimulation (reviewed in references 5 and 39).

The major subpopulations of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) are known to be infected in vivo and support viral replication in vivo and in vitro (reviewed in reference 5). Although MV infection of lymphocytic and monocytic cells was found to induce apoptosis (13, 14, 44) and to interfere with cell cycle progression (28–30, 48), this may only partially account for the general immunosuppression observed. This is because the number of infected cells is low during acute infection, and infection of PBMC usually does not induce syncytium formation to a large extent. Thus, indirect mechanisms are likely to play a major role. These may include production of as-yet-unidentified soluble factors released from infected B and T cells (16, 43) or signals provided to uninfected lymphocytic-monocytic cells following receptor ligation (21, 35, 37, 38). These mechanisms appear particularly attractive, since they might explain how the low proportion of infected PBMC found during acute infection can interfere with the function of an excess amount of uninfected cells.

Using a mixed proliferation assay, we have shown that the expression of MV glycoproteins F and H on MV-infected cells, cells transfected to express these proteins (presenter cells [PC]), or UV-inactivated MV is necessary and sufficient to induce unresponsiveness toward mitogenic, allogenic, and CD3-stimulated proliferation of both human and rodent peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) (responder cells [RC]) (12, 36, 40, 41). T-cell unresponsiveness could also be induced after transfer of these PC into cotton rats (Sigmodon hispidus) (31, 32). Cell cycle retardation rather than apoptosis was induced in RC under these conditions (31, 40), and it has recently been shown that this particular retardation was associated with a marked deregulation of cellular G1 cyclin-cdk complexes on the level of expression and activity (12).

In addition to its role in MV-induced immunosuppression, the MV F-H complex is well known to mediate fusion during MV entry and between infected cells (17, 24). Cleavage of the F0 protein precursor into the F1-F2 subunits by a cellular protease, most likely furin, is essentially involved in this process (4, 45). Fusion is thought to be initiated following conformational changes within the F1-F2 protein triggered after receptor interaction of the H protein (17, 24). Since fusion between PC and RC coculture occurred to a certain extent in our system, particularly when both PC and RC of human origin were used, we aimed at defining to what extent fusion contributes to MV-induced immunosuppression in vitro. We now show that fusion, but not the proliferative inhibition of RC, is affected in the presence of fusion-inhibitory peptides. As for fusion, however, proteolytic processing of the F protein precursor is a prerequisite for the induction of proliferative unresponsiveness by MV-infected PC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Lymphoid cell lines (BJAB, human lymphoblastoid B cells, and B95a, an adherent subclone of Epstein-Barr virus-transformed marmorset B cells) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), and Vero cells (African green monkey kidney) were maintained in minimal essential medium containing 5% FCS. Murine fibroblastic cells (Ltk-H cells stably expressing the MV Halle H protein [L-H] [3]), kindly provided by Fabian Wild, Institut Pasteur de Lyon, Lyon, France, were maintained in Dulbecco minimal essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FCS and 1 mg of G418 (Gibco BRL, Karlsruhe, Germany) per ml. LoVo cells (human colon adenocarcinoma) were grown in 50% Ham's F-12 medium and 50% DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS. PBMC were isolated by Ficoll-Paque (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany) density gradient centrifugation of heparinized blood obtained from healthy adult donors and were depleted of monocytes by plastic adherence. PBL were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FCS.

MV vaccine strain Edmonston B (MV-ED) was grown and propagated on Vero cells. The recombinant MV-Fcm was grown and propagated as described elsewhere (26a). Briefly, a monolayer of Vero cells was infected with MV-Fcm for 2 h, washed, and incubated for 15 h in DMEM before the addition of tolylsulfonyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin (1 μg/ml) (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany). Virus was harvested 48 h later by two rounds of freezing-thawing. Titers obtained on Vero cells were 5 × 106 PFU/ml for MV-ED and 107 50% tissue culture infective doses/ml for MV-Fcm.

Plaque reduction assay.

The assay was performed as previously described (34) with modifications. Monolayers of Vero or B95a cells were infected in six-well plates with MV-ED (100 PFU/well). After 1 h of adsorption, the medium was replaced by an agar overlay containing fusion-inhibitory peptides (Z-fFG) (Bachem, Heidelberg, Germany) (33, 34) or a peptide corresponding to the heptad repeat B (HRB) domain (46) of the MV-ED F protein (ISLERLDVGTNLGNAIAKLEDAKELLESSDQILRS) with solid-phase synthesis by D. Palm, Theodor-Boveri-Institut für Biowissenschaften, University of Würzburg, or a control peptide (Z-GFA) (Bachem) at the concentrations indicated. Cells were stained with neutral red after 48 to 72 h, and plaque numbers were determined after a further 10 h. Plaque reduction was expressed as a percentage relative to the number of plaques obtained in the absence of peptides.

Antibodies.

Cell surface staining was performed using monoclonal antibodies (MAb) directed against MV-ED protein F (MV F) (A5047) or MV-ED protein H (MV H) (K83, L77, NC32, K71, and K29; all generated in our laboratory). A monospecific serum against the cytoplasmic domain of the MV F protein [NH2-(C)PDLTGTSKSYVRSL-COOH] was obtained after immunization of rabbits as described previously (19).

Rosetting assay.

BJAB cells were infected with MV-ED (multiplicity of infection [MOI], 0.5) for 24 h or MV-Fcm (MOI, 1) for 40 h, stained for the expression of MV H protein and used in a rosetting assay. After three washing steps (in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]), 105 cells were resuspended in 200 μl of PBS and incubated with 0.2% (final concentration) of monkey erythrocytes for 1 h at 37°C. Rosette-forming cells were gently resuspended and cells rosetting three or more erythrocytes were counted in a hemocytometer.

Western blot analysis.

Cells were lysed at the time points indicated in radioimmunoprecipitation assay detergent (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 1% sodium desoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and equal amounts of total protein lysates were loaded, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. A rabbit serum raised against the cytoplasmic tail of the MV F protein (19), followed by a peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (Calbiochem-Novabiochem, Bad Soden, Germany) and an ECL detection kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) were used for the subsequent detection of F-specific bands.

In vitro proliferation assay.

PC were generated by infection of LoVo cells or BJAB cells with MV-ED or the recombinant MV-Fcm at the MOIs and intervals indicated. Alternatively, LoVo or BJAB cells persistently infected with MV-ED (LoVo-EDp or BJAB-EDp) were used. When indicated, LoVo-EDp cells and BJAB cells infected with the MV-Fcm recombinant, as well as (for control) mock-infected LoVo or BJAB cells, were treated with trypsin at the concentrations and intervals indicated. L-H cells were suspended (in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free PBS, 1 mM EDTA) 48 h following transfection with 3 μg of pCG-F or pCG-Fcm plasmid (26a), respectively, using Superfect (Gibco BRL), washed, and stained for the MV-specific cell surface proteins F and H by a mixture of MAb against the MV F and H proteins. Cells expressing both glycoproteins on their surfaces were enriched by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). Cells transfected with the pCG control plasmid (3 μg) were used as controls. In general, PC were inactivated by UV irradiation in a biolinker (0.25 J/cm2) except for transfected L-H cells, which were inactivated by treatment with mitomycin C (Sigma) (50 μg/ml) for 2 h, followed by a 30-min incubation without mitomycin C and extensive washing. Aliquots of 105 RC (B95a cells or PBL in the presence of 2.5 μg of phytohemagglutinin (PHA) per ml were seeded onto a 96-well plate in a volume of 100 μl. The PC were added at the concentrations indicated in a volume of 100 μl per well and were incubated for 48 h. When indicated, fusion-inhibitory peptide or the control peptide was added to the cocultures at the concentrations indicated. Proliferation rates were determined following a 16-h labeling period with [3H]thymidine (0.5 μCi/200 μl). Assays were routinely performed in triplicate and harvested, and the incorporation rates of [3H]thymidine were determined using a β-plate reader. Proliferative inhibition (expressed as a percentage) of the RC was determined relative to the proliferation rate seen in cocultures with control cells.

Cocapping assay.

The assay was performed as described previously (20) with modifications. BJAB cells were infected with MV-Fcm or MV-ED at an MOI of 1. One hour following adsorption, Z-fFG was added to the MV-ED-infected cells at a final concentration of 100 μg/ml to prevent syncytium formation. Forty-eight hours postinfection, cells were washed with PBS–0.4% FCS, pelleted by centrifugation, and divided into two aliquots which were incubated with a primary MAb against the MV F protein in PBS–0.4% FCS for 60 min at 0°C. Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS–0.4% FCS. One aliquot was incubated with the secondary antibody conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) in FACS buffer (PBS–0.2% bovine serum albumin–0.02% NaN3 [pH 7.4]) at 0°C for 1 h and subsequently washed with this buffer. The other aliquot was incubated with the secondary FITC-conjugated antibody in 100% FCS at 4°C for 1 h, shifted for a further 3 h to 37°C, and washed in PBS–0.4% FCS. Cells were then incubated with biotinylated MAb against the MV H protein or the human HLA-DR molecule (exalpha, Boston, Mass.) in PBS–0.4% FCS or with a biotinylated MAb against the MV H protein in FACS buffer, respectively, for 30 min at 0°C and washed in PBS–0.4% FCS or FACS buffer, respectively. Streptavidin conjugated to Texas Red-X (Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands) was added in PBS–0.4% FCS or FACS buffer, respectively, for 30 min at 0°C. Finally, cells were washed, fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde, resuspended in FACS buffer, mounted, and examined with a confocal microscope.

RESULTS

MV-induced immunosuppression is independent of cell fusion.

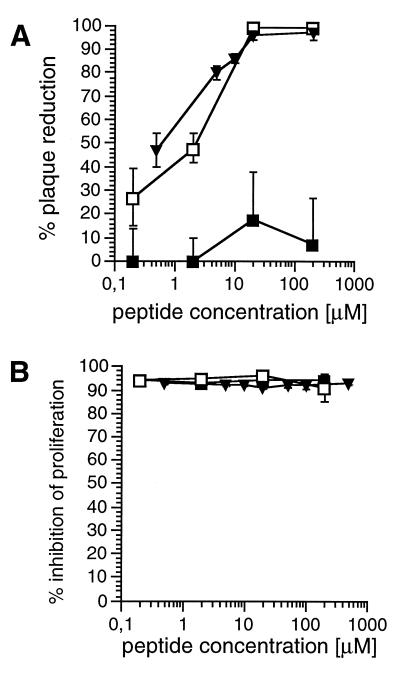

Expression of both MV glycoproteins F and H on the surface of MV-infected, UV-irradiated PC, UV-inactivated MV particles, or 293 cells transfected with the corresponding expression constructs was required and sufficient to induce unresponsiveness to mitogen stimulation in freshly isolated human PBL (RC) both in vitro and in an experimental animal model (32, 36). Since these proteins are also mediators of virus-induced cell fusion, we aimed on analyzing the extent to which PC-RC fusion contributes to MV-induced immunosuppression in vitro. For this purpose, the impact of two fusion inhibitory peptides (Z-fFG or a 35-mer peptide corresponding to the membrane proximal domain of MV F protein [HRB peptide]) on both virus-induced cellular fusion and induction of mitogen unresponsiveness in RC was tested. Both the Z-fFG and the HRB peptides, but not the control peptide (Z-GFA), completely abolished syncytium formation at concentrations higher than 25 μM when added to MV-ED-infected Vero or B95a cells, respectively, in a plaque reduction assay (Fig. 1A). Neither of the peptides interfered with the proliferation of B95a cells at concentrations up to 1 mM (results not shown). These cells were then used as RC in a cocultivation assay with persistently MV-infected, UV-inactivated BJAB-EDp cells as PC (PC/RC ratio, 1/10). Proliferative inhibition of the B95a cells as determined by [3H]thymidine labeling after 48 h was 95% in the absence of added peptides. Neither the control peptide, Z-fFG, or the HRB-peptide interfered with the induction of proliferative inhibition of B95a cells when added during this coculture up to concentrations of 1 mM (Fig. 1B). Thus, fusion but not the immunosuppressive activity of MV glycoproteins is sensitive to peptide-mediated inhibition, indicating that PC-RC fusion does not contribute to MV-induced immunosuppression in vitro.

FIG. 1.

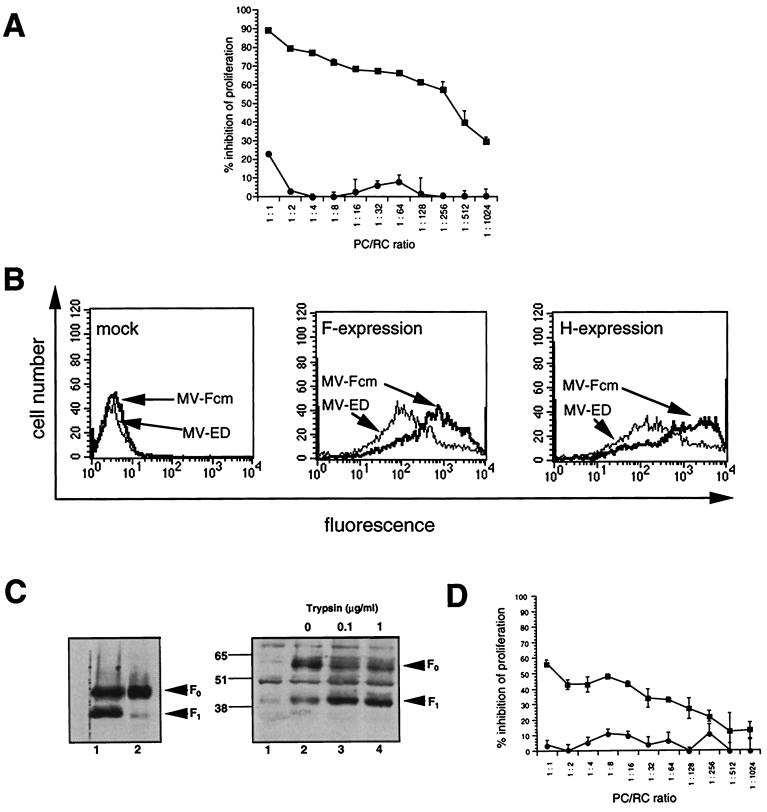

Influence of fusion-inhibiting peptides on proliferative inhibition of B95a cells by BJAB-EDp cells. (A) Agar overlays containing Z-fFG (□) (or, for control, Z-GFA [■]) or the HRB-peptide (▾) were applied at the concentrations indicated to monolayers of Vero cells or B95a cells 1 h following MV infection (100 PFU). The fusion-inhibitory activity of the peptides was determined 72 h postinfection by the reduction of plaque numbers (as a percentage) obtained in the absence of peptides. (B) Uninfected BJAB cells or persistently MV-infected BJAB-EDp cells were UV inactivated (PC) and cocultivated with B95a cells (RC) (PC/RC ratio, 1/10) in the presence of HRB (▾), Z-fFG (□), or Z-GFA (■) peptides at the concentrations indicated. Proliferative activity of the RC was determined after 48 h by a 16-h labeling period. Proliferative inhibition compared to RC in the presence of uninfected PC was determined.

The immunosuppressive activity of MV-infected PC in vitro is dependent on efficient proteolytic cleavage of the MV F protein.

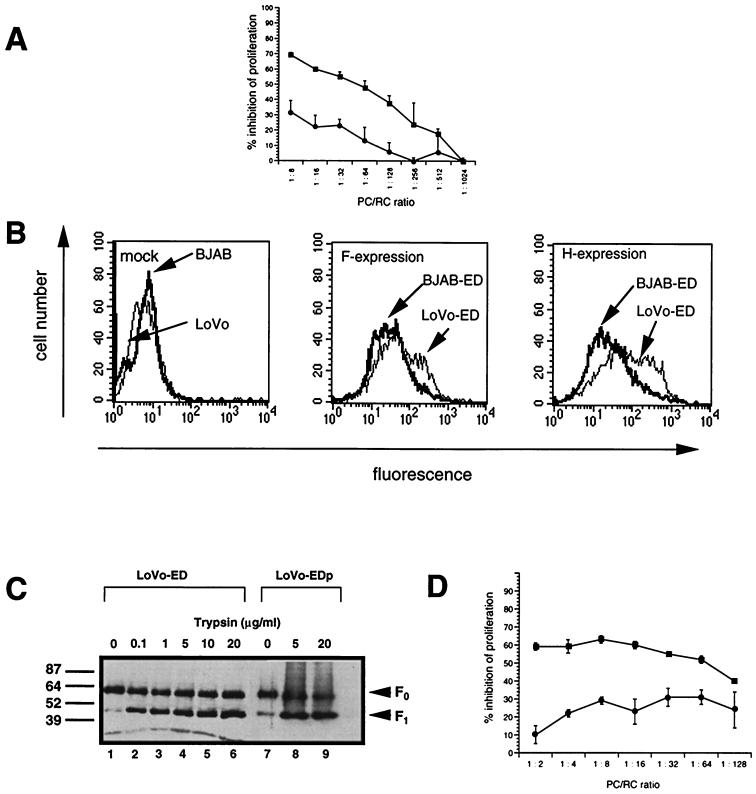

Proteolytic processing of the MV F0 protein by cellular furin, a subtilisin-like protease (42), is essential for its fusogenic activity. We wished to assess whether this cleavage would also be required for MV-induced proliferative inhibition in vitro. Thus, the ability of LoVo cells unable to produce functional furin (45) to serve as PC after MV infection was compared to that of MV-infected BJAB cells. Proteolytic processing of the F0 protein into the F1 and F2 subunits (the F2 subunit was not visible in this and all subsequent experiments, since we used an antiserum raised against the carboxy-terminal domain of F protein) was highly inefficient after primary and persistent MV infection of LoVo cells (Fig. 2C, lanes 1 and 7) compared to that of BJAB cells (Fig. 3A, lane 1), although low levels of the F1 cleavage product were still seen. Since the concentration of MV glycoproteins on the surface of the PC is a crucial parameter for their immunosuppressive activity, the expression levels of MV F and H proteins were determined on LoVo (MOI, 1) and BJAB (MOI, 0.1) cells after a 24-h MV infection. Under these conditions, the surface expression of both MV F and H was comparable to or slightly higher on MV-infected LoVo cells than on BJAB cells (Fig. 2B). When used as PC in our mitogen-dependent proliferation assay, MV-infected LoVo cells were, however, less efficient by far in inducing proliferative inhibition than MV-infected BJAB cells at any PC-RC concentration applied (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Proliferative inhibition by MV-infected LoVo cells is dependent on exogenous trypsin treatment. (A) MV-infected LoVo cells (●) (MOI, 1) and BJAB cells (■) (MOI, 0.1) were UV inactivated 24-h postinfection and used as PC for cocultivation with mitogen-stimulated human PBL (RC) at the PC/RC ratios indicated for 48 h, followed by a 16-h labeling period. Proliferative inhibition was determined in comparison to RC cocultivated with uninfected LoVo or BJAB cells, respectively. (B) MV-infected cells shown in panel A were stained for the surface expression of MV H and F proteins by using specific antibodies and subsequently analyzed by FACS scanning. Mock-infected cells were stained with an F-specific antibody. (C) LoVo-ED cells (MOI, 1; 24 h postinfection) (lanes 1 to 6) or LoVo-EDp cells (lanes 7 to 9) were treated with trypsin for 1 h at the concentrations indicated. Trypsin was inactivated in the presence of 10% FCS and lysates were prepared and analyzed for the expression of MV F protein by Western blotting. (D) Persistently MV-infected LoVo-EDp cells were treated with 20 μg of trypsin per ml for 1 h (■) or left untreated (●), UV inactivated, and used as PC for a standard cocultivation assay with mitogen-stimulated human PBL (RC) at the PC/RC ratios indicated. Proliferative inhibition was determined compared to RC cocultivated with uninfected LoVo cells treated or untreated with trypsin. One of three experiments is shown.

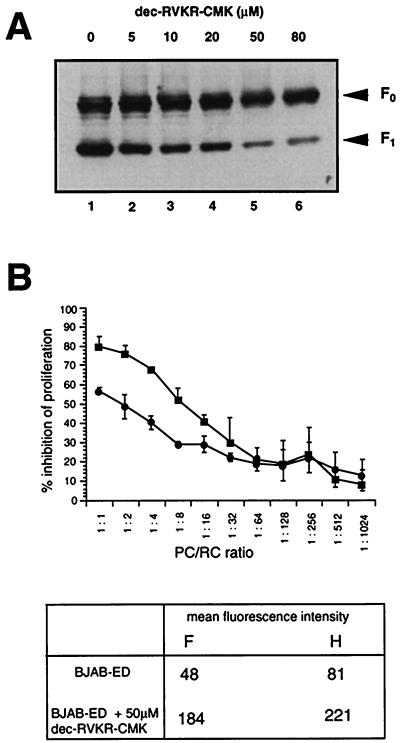

FIG. 3.

Both proteolytic cleavage of the F0 protein and the inhibitory activity of MV-infected BJAB cells are impaired in the presence of the furin inhibitor dec-RVKR-cmk. (A) dec-RVKR-cmk was added to BJAB cells 1 h following MV infection (MOI, 0.5) at the concentrations indicated. Cell lysates were prepared after 24 h and F protein expression was analyzed by Western blotting. The F0 and F1-specific signals are indicated. (B) BJAB cells were infected with MV (MOI, 0.1) and left untreated (■) or were infected (MOI, 0.5) and treated with 50 μM dec-RVKR-cmk 1 h following adsorption (●). Cells were UV inactivated 24 h postinfection and used as PC in a standard cocultivation assay with PHA-stimulated human PBL as RC at the ratios indicated (top). Proliferative inhibition was determined relative to the corresponding controls (uninfected BJAB cells in the presence or absence of dec-RVKR-cmk). Prior to cocultivation with RC, aliquots of the infected PC were stained and analyzed for the surface expression levels of MV F and H proteins by a FACS scan. Under these infection conditions, a comparable percentage of cells stained for MV surface proteins both in the presence and absence of dec-RVKR-cmk. The values indicated in the table (bottom) refer to the mean fluorescence intensities of these proteins.

To test whether exogenous processing of the F0 protein would restore their inhibitory activity, LoVo cells were trypsin treated 24 h postinfection. F1 accumulated to high levels after a 1-h digestion with increasing concentrations of trypsin (Fig. 2C, lanes 1 to 6). To avoid variances in MV glycoprotein expression as observed after primary infection, LoVo cells were persistently infected with MV-ED (LoVo-EDp cells). LoVo-EDp cells expressed high levels of the MV glycoproteins as revealed by surface staining (not shown) and by Western blot analyses (Fig. 2C, lane 7). As for freshly infected LoVo cells, cleavage of the F0 protein was induced by trypsin treatment (Fig. 2C, lanes 8 and 9). As found with freshly infected LoVo cells, LoVo-EDp cells revealed a low level of activity when used as PC to inhibit mitogen-dependent RC proliferation (Fig. 2D). After trypsin treatment, however, their inhibitory activity was significantly enhanced, indicating that proteolytic processing of the MV F protein is required for the induction of immunosuppression in vitro (Fig. 2D). To further confirm this assumption, BJAB cells were MV-infected with an MOI of 0.5 for 24 h in the presence of a furin inhibitor (dec-RVKR-cmk [42]). At a concentration of 50 μM inhibitor, a significant reduction of F0 protein cleavage was observed (Fig. 3A), and giant cell formation was completely abolished (data not shown). MV-infected BJAB cells kept in the presence of dec-RVKR-cmk, however, revealed a reduced ability to induce proliferative arrest of mitogen-stimulated RC compared to untreated controls, although the presence of dec-RVKR-cmk did not interfere with the surface expression of the MV glycoproteins (Fig. 3B) and did not affect the viability and proliferative activity of both BJAB cells or mitogen-stimulated PBL when directly applied into the medium (not shown).

Immunosuppression in vitro is not induced when an F protein cleavage mutant is coexpressed with MV H protein.

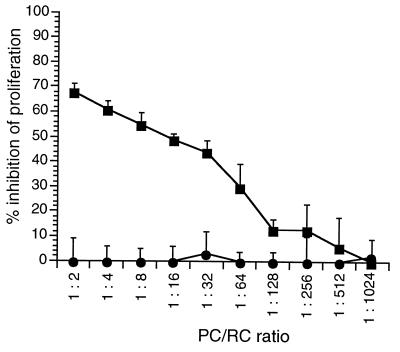

To further confirm the importance of the proteolytic processing of the F protein for MV-induced immunosuppression in vitro, we assessed the inhibitory activity of a cleavage mutant of the MV F protein coexpressed with MV H protein in transient transfection assays. For this purpose, the authentic cleavage sequence within the F0 precursor (RRHKR-FA) was mutated to (RNHNR-FA) to yield pCG-Fcm (26a). Only trace amounts of F1 protein were detectable in extracts of HeLa cells transfected with this construct, whereas the major proportion of this protein was uncleaved F0 (26a; data not shown). As was seen in the controls with the authentic MV F protein, the mutant protein was transported to the cell surface and the expression levels were also comparable (not shown). L-H cells were transfected to express the authentic MV F protein (pCG-F) or the cleavage mutant (pCG-Fcm). Syncytium formation was not observed in either transfection assay (data not shown). F protein-positive cells from both transfection assays were sorted, inactivated by mitomycin C treatment, and used as PC in a cocultivation assay with mitogen-stimulated human PBL at various PC/RC ratios. Whereas L-H cells expressing the authentic F protein were strongly inhibitory, those expressing Fcm protein completely failed to induce immunosuppression in vitro (Fig. 4). We further extended these analyses by using a recombinant MV-ED in which the authentic F gene was replaced by the Fcm sequence (26a). When the cleavage mutant was used to infect BJAB cells, the F1 protein subunit was detected only at very low levels (Fig. 5C). Since the MV-Fcm recombinant did not spread in the cultures in the absence of trypsin, a higher MOI of this recombinant had to be used to generate PC than for the authentic MV-ED strain. Under these conditions, the levels of MV glycoproteins expressed on the surface were comparable for MV-ED and MV-Fcm infection after 48 h (Fig. 5B). When used as PC, BJAB cells were, however, only inhibitory after infection with MV and completely inactive after infection with the MV-Fcm recombinant (Fig. 5A). To test whether the inhibitory activity of BJAB-MV-Fcm-infected cells could be restored, these cells were subjected to trypsin treatment, which led to the accumulation of the F1 protein subunit (Fig. 5C, lanes 3 and 4). To generate PC, BJAB cells were infected with MV-Fcm (MOI, 1) for 24 h and then treated with trypsin for a further 24 h or left untreated. After a total infection period of 48 h, formation of syncytia was observed in the cultures kept in the presence of trypsin (not shown). When used as PC, trypsin-activated MV-Fcm-infected BJAB cells partially regained their inhibitory activity compared to untreated MV-Fcm-infected cells (Fig. 5D). Taken together, these findings indicate that the F0 protein cleavage is an essential prerequisite for the inhibitory activity of MV glycoproteins.

FIG. 4.

L-H cells transfected to express an F protein cleavage mutant fail to induce proliferative inhibition of RC. L-H cells were transfected with pCG-Fcm (●) containing a mutated cleavage site or pCG-F (■). Cells doubly positive for MV F and H surface expression were sorted 48 h later, inactivated by mitomycin C treatment, and used as PC in a standard cocultivation assay with mitogen-stimulated human PBL. Values indicated for proliferative inhibition were determined in comparison to controls (L-H cells transfected with the empty pCG vector).

FIG. 5.

The inhibitory activity of BJAB cells infected with a recombinant MV cleavage mutant (MV-Fcm) depends on exogenous trypsin treatment. (A) BJAB cells infected with MV (MOI, 0.1) (■) or MV-Fcm (MOI, 1) (●) for 48 h were UV inactivated and used as PC in a standard cocultivation assay with PHA-stimulated human PBL as RC. Proliferative inhibition (expressed as a percentage) obtained in triplicate assays was determined in comparison to mock-infected BJAB cells. One of three experiments is shown. (B) Prior to UV inactivation, aliquots of the mock-, MV-, or MV-Fcm-infected cells (shown as PC in Fig. 5A) were stained and analyzed by FACS scanning for the surface expression of MV F and H proteins. (C) BJAB cells were infected with MV (MOI, 0.5) (left panel, lane 1) or MV-Fcm (MOI, 1) (left panel, lane 2), lysed after 24 h, and analyzed for F protein expression and proteolytic processing by Western blotting. Alternatively, BJAB cells infected with MV-Fcm (MOI, 1) were incubated with trypsin 24 h postinfection at the concentrations indicated for 1 h at 37°C and subsequently processed for Western blot analysis (right panel, lanes 2 to 4). Lane 1, mock-infected BJAB cells. MV-F-specific bands are indicated by arrowheads. (D) BJAB cells were infected with the MV-Fcm recombinant (MOI, 1) for 24 h, treated with trypsin (1 μg/ml; 24 h at 37°C) (■) or left untreated (●) and used as PC in a standard cocultivation assay with human PHA-stimulated PBL at the PC/RC ratios indicated. Values indicated for proliferative inhibition (expressed as a percentage) were determined compared to mock-infected BJAB cells treated or untreated with trypsin, respectively.

MV H protein efficiently interacts with both MV F and Fcm proteins on the cell surface, and its conformation and hemagglutination activities are not altered in the absence of F protein cleavage.

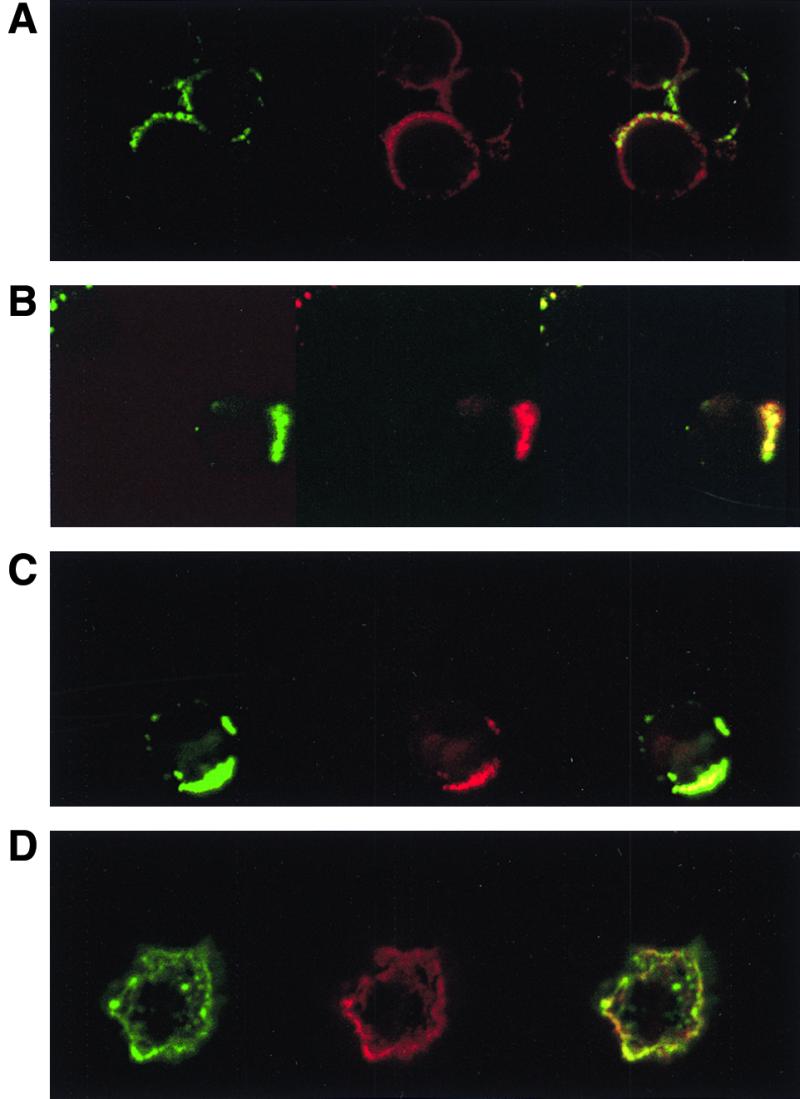

We previously found that the MV glycoproteins need to be coexpressed on the surface of PC in order to exert their inhibitory activity (36), suggesting that complex formation between F and H proteins is required. It is possible that the low immunosuppressive activity of PC expressing mainly F0-H proteins was based on the failure of these proteins to interact on the cell surface. To address this aspect, we established a cocapping assay using BJAB cells infected with either MV-ED (Fig. 6C and D) or the MV-Fcm recombinant (Fig. 6A and B). For this purpose, infected cells were treated with an F-specific antibody at 4°C, followed by incubation with a cross-linking antibody at 37°C (Fig. 6A to C) or at 4°C (Fig. 6D). To evaluate redistribution of the H protein, the cells were subsequently stained using an H-specific antibody (Fig. 6B to D), or, for control, an HLA-DR-specific antibody (Fig. 6A). Whereas no capping was seen when the temperature shift was omitted (Fig. 6D) and cocaps of F protein with HLA-DR molecules were observed only to a minimal extent (Fig. 6A), H protein cocapped with both the authentic F (Fig. 6C) and the Fcm (Fig. 6B) proteins to a similar extent. These findings indicate that both proteolytically cleaved as well as uncleaved F proteins interact with the MV H protein with similar efficiency at the cell surface, and therefore, the failure of F0-expressing cells to induce immunosuppression in vitro does not result from the lack of F0-H surface complexes.

FIG. 6.

Both MV F and MV F0 protein cocap with MV H protein. BJAB cells were infected with MV-ED (MOI, 1) with 100 μg of Z-fFG per ml added following adsorption to prevent syncytium formation (C and D) or MV-Fcm (MOI, 1) (A and B). Forty-eight hours postinfection, cells were incubated with an MV-F-specific MAb at 4°C for 60 min and subsequently with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G at 4°C for 1 h, followed by an incubation at 37°C for 3 h (A to C) or at 4°C for 1 h (D). Biotinylated MAb against the MV H protein (B to D) or HLA-DR (A) were then applied for 30 min at 4°C, followed by an incubation with streptavidin-Texas Red for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were examined with a confocal microscope. Left, FITC stainings of the MV-F protein; middle, Texas-Red stainings of the MV H protein (B to D) or the HLA-DR molecule (A): right, overlay of both signals.

To assess whether the conformation of the MV H protein would be influenced by the absence of F protein cleavage, we tested for the binding of five different MV-H-specific MAb to BJAB cells infected with MV-ED (MOI, 0.5) or MV-Fcm (MOI, 1) at 24 or 40 h, respectively. Under these conditions, both the number of cells staining positive for the H protein and the mean fluorescence intensities were comparable with all MAb applied (Table 1), indicating that the lack of F protein processing was not associated with gross structural changes in the H protein. Moreover, the efficiency to agglutinate monkey erythrocytes was comparable for BJAB-MV-ED and BJAB-MV-Fcm cells (Table 1). Thus, the abolishment of F protein cleavage does not interfere with H protein interaction and does not affect structure and function of the H protein.

TABLE 1.

Binding of MAb to and hemagglutinating activity of MV H protein in MV-ED- or MV-Fcm-infected BJAB cells

| BJAB cell type | Rosette-forming cells (%)a | Cell surface binding of MAbb (MFI/% of positive cells)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L77 | K83 | NC32 | K71 | K29 | ||

| MV-Fcm | 64 ± 3 | 86/66 | 95/70 | 152/86 | 90/78 | 285/94 |

| MV-ED | 71 ± 1 | 68/71 | 81/73 | 175/87 | 82/77 | 200/89 |

Determined by rosetting of at least three monkey erythrocytes in a hemocytometer. Values represent percentages ± standard errors of the mean.

Determined by binding of the H-specific MAb L77, K83, NC32, K71, and K29 to the surface of BJAB cells infected with MV-Fcm (MOI, 1; 40 h postinfection) or MV-ED (MOI, 0.5; 24 h postinfection) by FACS scan. For negative control, uninfected BJAB cells were stained with the same antibodies. MFI, mean fluorescence intensities.

DISCUSSION

Inhibition of lymphocyte proliferation in response to a variety of mitogenic stimuli is thought to be a central finding in MV-induced immunosuppression (reviewed in references 5, 22, and 39). Mechanisms accounting for this induction of unresponsiveness may include direct infection of these cells (28–30, 48) or indirect mechanisms, such as the production of inhibitory soluble factors from infected cells (15, 43) or direct negative signalling to T cells or monocytes exerted by MV surface glycoproteins (14, 21, 32, 36, 40). In support of the latter hypothesis, we found that the presence of the MV glycoproteins F and H on the surface of infected cells, cells transfected to express these proteins (PC), or MV particles is necessary and sufficient to induce a state of unresponsiveness to mitogenic stimulation in freshly isolated human and rodent lymphocytes (RC) (12, 36, 40). In addition, spontaneous proliferation of lymphocytic and monocytic cell lines, but not of adherent cells, was affected in the presence of MV-infected PC (36, 40, 41). Our recent finding that B95a cells which grow in adherence (Fig. 1B), but not HeLa S3 cells which grow in suspension (data not shown), are sensitive to MV glycoprotein-mediated inhibition supports the notion that a hematopoietic origin, rather than adherence, may define susceptibility to MV-mediated immunosuppression.

From our data, it appears that MV F and H, coexpressed on the cell surface most likely as complexes, are effector structures inducing immunosuppression in vitro and in an experimental animal model (32). These proteins are, however, also known to mediate membrane fusion during viral entry and spread (17, 24). Although observed in our in vitro assays to a certain extent when both RC and PC were of human origin, fusion-mediated loss of RC is unlikely to contribute to MV-induced immunosuppression in our system, since (i) adherent cells of nonhematopoietic origin efficiently fuse with PC but however do not show any proliferative inhibition (36), (ii) primary mitogen-stimulated rodent lymphocytes are sensitive to MV glycoprotein-induced inhibition but undergo syncytium formation only after transgenic expression of CD46 (31), and (iii) as shown in this study, peptides with a defined fusion inhibitory activity such as Z-fFG (33, 34) and the HRB peptide (47) did not interfere with the induction of proliferative inhibition of B95a cells by MV-infected PC (Fig. 1). The ability of both peptides to interfere with membrane fusion has been well documented in the past; however, their precise mode of action is not completely understood. Z-fFG, an oligopeptide with similarity to the amino-terminus of the paramyxovirus F1 fusion domain, is thought to interfere with perturbation of the recipient cell's membrane by the authentic F1 termini by stabilizing the lamellar phase and inhibiting its transition to the hexagonal phase of the lipid layers (1, 11, 25, 33, 34). Two other domains with predicted α-helical structures have additionally been identified as important for membrane fusion mediated by paramyxovirus F proteins—the heptad repeat domain A or 1, which is located just carboxy terminal to the fusion domain, and the HRB or heptad repeat 2 domain, located adjacent to the transmembrane domain of the F protein (7, 8, 24, 46, 47). There is increasing evidence that disruption of the α-helical conformation after the mutation of leucine residues does not interfere with intracellular transport, surface expression, or oligomerization of the F proteins, although it does, however, prevent its fusogenic ability (49, 50). As suggested for simian virus 5 (SV5) F protein by a recent study, peptides corresponding to the HRB domain inhibit both lipid and aqueous content mixing during fusion, while those corresponding to the HRA domain only interfere with aqueous phase mixing and lead to a hemifusion state (2). Since membrane fusion by the SV5 F protein might differ from that of the MV F protein and the precise targets for the MV fusion inhibitory peptides during membrane fusion are not known yet, we cannot rule out that intermediate steps of membrane fusion, such as lipid mixing during hemifusion, would be required for the induction of immunosuppression in vitro. Although fusion is not required for the induction of immunosuppression, proteolytic processing of the F0 protein apparently is. As for an increasing number of viral glycoproteins mediating membrane fusion, proteolytic processing of the MV F0 precursor essentially occurs by cellular furin, a subtilisin-like serine protease located in the trans-Golgi network (4, 45). This is because LoVo cells unable to produce functional furin largely fail to cleave the F0 protein into its subunits (45) (Fig. 2C), and a furin inhibitor (dec-RVKR-cmk) (42) efficiently prevents F0 protein processing in MV-infected BJAB cells (Fig. 3A). The synthesis of F protein was not impaired, and F protein was expressed to high levels on the surface of infected BJAB cells in the presence of the inhibitor (Fig. 3B) and on MV-infected LoVo cells (Fig. 2). Syncytium formation did not occur in infected LoVo cell cultures and in dec-RVKR-cmk-treated BJAB cells (data not shown) although F1 cleavage products were still detectable by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2 and 3). This was most likely due to the formation of heterooligomers of cleaved and uncleaved forms of F protein in which the uncleaved F0 is thought to exert a dominant negative effect, as is shown for Newcastle disease virus (26). For the same reason, cells infected with a recombinant F protein cleavage mutant, MV-Fcm, do not induce membrane fusion in the absence of trypsin, although low amounts of F1 can also be detected by Western blot analysis (Fig. 5C). Both membrane fusion and immunosuppressive activity were, however, partially restored after trypsin treatment of MV-infected LoVo cells (Fig. 2) or BJAB cells infected with the MV-Fcm recombinant (Fig. 5). It is quite likely that trypsin cleavage led to the generation of authentic F1 termini in these cases, since (i) cleavage products obtained were active in inducing syncytium formation (26a; data not shown) and (ii) only one major cleavage product was detected on Western blots (Fig. 2C and 5C).

Due to the inability of MV-Fcm to spread in the cultures in the absence of trypsin, generally higher-input MOIs had to be used as with MV-ED to obtain an appropriate amount of MV glycoprotein-expressing PC. Trypsin treatment of these cells allowed the formation of syncytia and the release of infectious virus (26a; data not shown). Thus, it is quite possible that the PC population obtained in the presence of trypsin did actually contain a higher percentage of cells expressing the MV glycoproteins than the untreated control, since the virus could have spread within the 24 h of trypsin treatment (Fig. 5). This is, however, unlikely to account for the higher immunosuppressive activity of MV-Fcm-infected BJAB cells after trypsin treatment, since cells expressing mainly F0 and H proteins were not suppressive, even at high PC/RC ratios (Fig. 4 and 5A and D).

In contrast to related viral systems, attempts to firmly document the physical interaction of MV F and H proteins, e.g., by coimmunoprecipitation, have not been entirely convincing. Based on our cocapping studies, the inability of mainly F0- and H-expressing cells to induce immunosuppression is not likely to result from the failure of F0 to interact with H protein on the cell surface (Fig. 6). Since viruses released from MV-Fcm-infected cells (26a) and from certain B-cell lines found to be rather inefficient in proteolytic activation of MV F0 protein (16) can be rendered infective, it is likely that F0-H complexes are formed at the cell surface and incorporated in viral particles. In contrast to these and our observations, Malvoisin and Wild (27) failed to detect an interaction of F0 protein with MV H in coimmunoprecipitation assays. In this study, the MV glycoproteins were expressed by recombinant vaccinia virus constructs, and F0 protein was almost completely cleaved into its subunits. Even in the presence of cross-linking agents, only very low levels of F1 were coprecipitated in these assays by an H-specific antibody. It is thus quite possible that the failure to detect the F0-H interaction in these experiments was due to the low concentration of F0 protein. Do our results imply that the domains critical for the induction of immunosuppression locate to the F protein, and if so, what then is the role of H protein? We have previously shown that 293 cells expressing F protein alone gain immunosuppressive activity in vitro and in vivo only after coexpression of the H protein (32, 36). Although fusion activity of the complex is not directly required, it is quite possible that the necessity of conformational changes within the F protein following proteolytic cleavage and/or interaction with the H protein may also apply for the immunosuppressive activity of this protein complex. For Sendai virus and Newcastle disease virus, which are closely related to MV, circular dichroism studies confirmed that conformational changes within the F protein occurred after proteolytic cleavage of the F0 protein, which were associated with an increase in its α-helical content (18, 23) and that the conformation of the viral glycoproteins in reconstituted viral envelopes is different from that when these proteins are expressed separately (9). Moreover, the MV F protein requires a precise distance to be bridged by the homotypic H protein to form a molecular scaffold that allows optimal receptor interaction (6). In this context, it is quite important that in the absence of F protein cleavage both the structure and the biological activity of the H protein are apparently retained (Table 1). Thus, it is quite possible that domains only exposed following proteolytic cleavage of the MV F0 protein play an essential role in the induction of immunosuppression. Their interaction with the target cell membrane requires (or is stabilized or prolonged following) the binding of the MV H protein to its cognate receptor(s). Based on our findings, it should now be possible to address domains within the MV F protein which are important for the induction of immunosuppression by MV in future experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H. D. Klenk, I. Johnston, J. Schneider-Schaulies, S. Niewiesk, and B. Rima for helpful discussions and critical comments on the manuscript and F. Wild for providing the L cell transfectants.

We thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the Robert Pfleger Stiftung, the WHO, and the Humboldt Foundation for financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aroeti B Y, Henis I. Accumulation of Sendai virus glycoproteins in cell-cell contact regions and its role in cell fusion. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:15845–15849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagai S, Dutch R E, Lamb R A. A core trimer of the paramyxovirus fusion protein: parallels to influenza virus hemagglutinin and HIV gp41. Virology. 1998;248:20–34. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beauverger P, Buckland R, Wild F. Establishment and characterisation of murine cells constitutively expressing the fusion, nucleoprotein and matrix proteins of measles virus. J Virol Methods. 1993;44:199–210. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(93)90055-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolt G, Pedersen I R. The role of subtilisin-like proprotein convertases for cleavage of the measles virus fusion glycoprotein in different cell types. Virology. 1999;252:387–398. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borrow P, Oldstone M B A. Measles virus—mononuclear cell interactions. In: ter Meulen V, Billeter M A, editors. Current topics of microbiology and immunology: measles virus. Vol. 191. Berlin, Germany: Springer Verlag; 1995. pp. 85–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchholz C J, Schneider U, Devaux P, Gerlier D, Cattaneo R. Cell entry by measles virus: long hybrid receptors uncouple binding from membrane fusion. J Virol. 1996;70:3716–3723. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3716-3723.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buckland R, Malvoisin E, Beauverger P, Wild T F. A leucine zipper structure present in the measles virus fusion protein is not required for its tetramerisation but is essential for fusion. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:1703–1707. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-7-1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chambers P, Pringle C R, Easton J J. Heptad repeat sequences are located adjacent to hydrophobic regions in several types of viral fusion proteins. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:3075–3080. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-12-3075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Citovsky V, Yanai P, Loyter A. The use of circular dichroism to study conformational changes induced in Sendai virus envelope glycoproteins. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:2235–2239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clements C J, Cutts F T. The epidemiology of measles: thirty years of vaccination. In: ter Meulen V, Billeter M A, editors. Current topics of microbiology and immunology: measles virus. Vol. 191. Berlin, Germany: Springer Verlag; 1995. pp. 13–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellens H, Siegel D P, Alford D, Yeagle P L, Boni L, Lis L J, Quinn P J, Bentz J. Membrane fusion and inverted phases. Biochemistry. 1989;28:3692–3703. doi: 10.1021/bi00435a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engelking O, Fedorov L M, Lilischkis R, ter Meulen V, Schneider-Schaulies S. Measles virus-induced immunosuppression in vitro is associated with deregulation of G1 cell cycle control proteins. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:1599–1608. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-7-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esolen L E, Park S W, Hardwick J M, Griffin D E. Apoptosis as a cause of death in measles virus-infected cells. J Virol. 1995;69:3955–3958. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3955-3958.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fugier-Vivier I, Servet-Delprat C, Rivailler P, Riossan M C, Liu Y L, Rabourdin-Combe C. Measles virus suppresses cell-mediated immunity by interfering with the survival and functions of dendritic and T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:813–823. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.6.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujinami R S, Sun X, Howell J M, Jenkins J C, Burns J B. Modulation of immune system function by measles virus infection: role of soluble factor and direct infection. J Virol. 1998;72:9421–9427. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9421-9427.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujinami R S, Oldstone M B A. Failure to cleave measles virus fusion protein in lymphoid cells. J Exp Med. 1981;154:1489–1499. doi: 10.1084/jem.154.5.1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernandez L D, Hoffman L R, Wolfsberg T G, White J M. Virus-cell and cell-cell fusion. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1996;12:627–661. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsu M, Scheid A, Choppin P W. Activation of the Sendai virus fusion (F) protein involved a conformational change with exposure of a new hydrophobic region. J Biol Chem. 1981;156:3557–3563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu A, Cathomen T, Cattaneo R, Norrby E. Influence of N-linked oligosaccharide chains on the processing, cell surface expression and function of the measles virus fusion protein. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:705–710. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-3-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joseph B S, Oldstone M B A. Antibody-induced redistribution of measles virus antigens on the cell surface. J Immunol. 1974;113:1205–1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karp C L, Wysocka M, Wahl L M, Ahearn J M, Cuomo P J, Sherry B, Trinchieri G, Griffin D E. Mechanism of suppression of cell-mediated immunity by measles virus. Science. 1996;273:228–231. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klagge I M, Schneider-Schaulies S. Virus interactions with dendritic cells. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:823–833. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-4-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohama T, Garten W, Klenk H D. Changes in conformation and charge paralleling proteolytic activation of Newcastle disease virus glycoproteins. Virology. 1981;111:364–376. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamb R A. Paramyxovirus fusion: a hypothesis of changes. Virology. 1993;197:1–11. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lambert D M, Barney S, Lambert A L, Guthrie K, Medinas R, Davis D, Bucy T, Erickson J, Merutka G, Petteway S R. Peptides from conserved regions of paramyxovirus fusion proteins are potent inhibitors of viral fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2186–2191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Z, Sergel T, Razvi E, Morrison T. Effect of cleavage mutants on syncytium formation directed by the wild-type fusion proteins of Newcastle disease virus. J Virol. 1998;72:3789–3795. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3789-3795.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26a.Maisner A, Mrkic B, Herrler G, Moll M, Billeter M A, Cattaneo R, Klenk H D. Recombinant measles virus requiring an exogenous protease for activation of infectivity. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:441–449. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-2-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malvoisin E, Wild T F. Measles virus glycoproteins: studies on the structure and interaction of the hemagglutinin and fusion proteins. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:2365–2372. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-11-2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McChesney M B, Kehrl J H, Valsamakis A, Fauci A S, Oldstone M B A. Measles virus infection of B lymphocytes permits cellular activation but blocks progression through the cell cycle. J Virol. 1987;61:3441–3447. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.11.3441-3447.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McChesney M B, Altman A, Oldstone M B A. Suppression of T lymphocyte function by measles is due to cell cycle arrest in G1. J Immunol. 1988;140:1269–1273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naniche D, Reed S I, Oldstone M B A. Cell cycle arrest during measles virus infection: a G0-like block leads to suppression of retinoblastoma protein expression. J Virol. 1999;73:1894–1901. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.1894-1901.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niewiesk S, Ohnimus H, Schnorr J J, Götzelmann M, Schneider-Schaulies S, Jassoy C, ter Meulen V. Measles virus-induced immunosuppression in cotton rats is associated with a cell cycle retardation in uninfected lymphocytes. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:2023–2030. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-8-2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niewiesk S, Eisenhuth I, Fooks A, Clegg J C, Schnorr J J, Schneider-Schaulies S, ter Meulen V. Measles virus-induced immune suppression in the cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus) model depends on viral glycoproteins. J Virol. 1997;71:7214–7219. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7214-7219.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richardson C D, Choppin P W. Oligopeptides that specifically inhibit membrane fusion by paramyxoviruses. Virology. 1983;131:518–532. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90517-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richardson C D, Scheid A, Choppin P W. Specific inhibition of paramyxovirus and myxovirus replication by oligopeptides with amino acid sequences similar to those at the N-termini of the F1 or HA2 viral polypeptides. Virology. 1980;105:205–222. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(80)90168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanchez-Lanier M, Guerlin P, McLaren L C, Bankhurst A D. Measles virus induced suppression of lymphocyte proliferation. Cell Immunol. 1988;116:367–381. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(88)90238-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schlender J, Schnorr J J, Spielhofer P, Cathomen T, Cattaneo R, Billeter M, ter Meulen V, Schneider-Schaulies S. Interaction of measles virus glycoproteins with the surface of uninfected peripheral blood lymphocytes induces immunosuppression in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13194–13199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider-Schaulies J, Schnorr J J, Dunster L, Schneider-Schaulies S, ter Meulen V. Receptor (CD46) modulation and complement-mediated lysis of uninfected cells after contact with measles virus-infected cells. J Virol. 1996;70:255–263. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.255-263.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneider-Schaulies J, Schnorr J-J, Brinkmann U, Dunster L, Baczko K, Schneider-Schaulies S, ter Meulen V. Receptor usage and differential downregulation of CD46 by measles virus wild type and vaccine strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3943–3947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schneider-Schaulies S, ter Meulen V. Measles virus induced immunosuppression. Nova Acta Leopold. 1999;307:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schnorr J J, Seufert M, Schlender J, Borst J, Johnston I C D, ter Meulen V, Schneider-Schaulies S. Cell cycle arrest rather than apoptosis is associated with measles virus contact-mediated immunosuppression in vitro. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:3217–3226. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-12-3217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schnorr J J, Xanthakos S, Keikavoussi P, Kämpgen E, ter Meulen V, Schneider-Schaulies S. Induction of maturation of human blood dendritic cell precursors by measles virus is associated with immunosuppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5326–5331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stienike-Gröber A, Vey M, Angliker H, Shaw E, Thomas G, Roberts C, Klenk H D, Garten W. Influenza virus hemagglutinin with multibasic cleavage site is activated by furin, a subtilisin-like protease. EMBO J. 1992;11:2407–2414. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun X, Burns J B, Howell J M, Fujinami R S. Suppression of antigen-specific T cell proliferation by measles virus infection: role of a soluble factor in suppression. Virology. 1998;246:24–33. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valentin H, Azocar O, Horvat B, Williems R, Garonne R, Evlashev A, Toribio M L, Rabourdin-Combe C. Measles virus infection induces terminal differentiation of human thymic epithelial cells. J Virol. 1999;73:2212–2221. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2212-2221.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watanabe M, Hirano A, Stenglein S, Nelson J, Thomas G, Wong T C. Engineered serine protease inhibitor prevents furin-catalyzed activation of the fusion glycoprotein and production of infectious measles virus. J Virol. 1995;69:3206–3210. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.3206-3210.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wild C, Dubay J W, Greenwell T, Baird J, Oas T G, McDanal C, Hunter E, Mathews T. Propensity for a leucine zipper like domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 to form oligomers correlates with a role in virus-induced fusion rather then assembly of the glycoprotein complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12676–12680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wild T F, Buckland R. Inhibition of measles virus infection and fusion with peptides corresponding to the leucine zipper region of the fusion protein. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:107–111. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-1-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yanagi Y, Cubitt B A, Oldstone M B A. Measles virus inhibits mitogen-induced T cell proliferation. Virology. 1992;187:280–289. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90316-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Young J K, Hicks R P, Wright G E, Morrison T G. The role of leucine residues in the structure and function of a leucine zipper peptide inhibitor of paramyxovirus (NDV) fusion. Virology. 1998;243:21–31. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Young J K, Hicks R P, Wright G E, Morrison T G. Analysis of a peptide inhibitor of paramyxovirus (NDV) fusion using biological assays, NMR and molecular modeling. Virology. 1997;238:291–304. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]