Abstract

Synthesis and characterization of DEMOFs (defect-engineered metal–organic frameworks) with coordinatively unsaturated sites (CUSs) for gas adsorption, catalysis, and separation are reported. We use the mixed-linker approach to introduce defects in Cu2-paddle wheel units of MOFs [Cu2(Me-trz-ia)2] by replacing up to 7% of the 3-methyl-triazolyl isophthalate linker (1L2–) with the “defective linker” 3-methyl-triazolyl m-benzoate (2L–), causing uncoordinated equatorial sites. PXRD of DEMOFs shows broadened reflections; IR and Raman analysis demonstrates only marginal changes as compared to the regular MOF (ReMOF, without a defective linker). The concentration of the integrated defective linker in DEMOFs is determined by 1H NMR and HPLC, while PXRD patterns reveal that DEMOFs maintain phase purity and crystallinity. Combined XPS (X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy) and cw EPR (continuous wave electron paramagnetic resonance) spectroscopy analyses provide insights into the local structure of defective sites and charge balance, suggesting the presence of two types of defects. Notably, an increase in CuI concentration is observed with incorporation of defective linkers, correlating with the elevated isosteric heat of adsorption (ΔHads). Overall, this approach offers valuable insights into the creation and evolution of CUSs within MOFs through the integration of defective linkers.

Short abstract

This work demonstrates that introducing defects into ultramicroporous MOFs via a mixed-linker approach markedly elevates their adsorption properties. This method, focusing on the strategic placement of CUSs within Cu2-paddle wheel units, leads to partial reduction of CuII to CuI and to an enhanced isosteric heat of H2 adsorption. The research underscores the significance of defect engineering in MOFs to modify MOF properties.

Introduction

Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) as one class of porous materials have attracted sustained interest over the past 25 years; their formation can be described as metal nodes (SBU) connected by organic linkers.1 These materials exhibit remarkable properties, including a high surface area, tunable porosity, and the potential for functionalization of coordination space, which make them superior candidates for gas storage, molecular separation,2,3 heterogeneous catalysis,4 sensing,4 etc. There is enormous interest arising in defect-engineered MOFs (DEMOFs).5−13 It is currently understood that defects can be used to alter the band gap,14,15 electrical conductivity,16−18 gas adsorption,7,12−17 and catalytic properties of MOFs.19−21 Experimental and theoretical studies have demonstrated that a controlled presence of structural defects can positively influence the physical and chemical characteristics of MOF materials.22−25 These defects can be a result of missing metal nodes or missing linkers, which can disrupt the regularity of the framework locally and result in the absence of either the full molecule or only a subset of functionalities when fragmented linkers are integrated.9,26,27 Defects can be generated in the MOFs by applying various strategies that are well established in the literature, i.e., de novo synthesis and postsynthetic7 treatment. The solid-solution approach in de novo synthesis allows for the integration of defects and modifications during the MOF’s formation, providing a uniform and precise distribution of components. This method has been used with success to produce DEMOFs.23,28−32 The nature of the incorporated linkers determines the type of resulting mixed-linker MOF, while the crystalline phase and topology of the framework are usually maintained.33 For example, the synthesis of HKUST-1 in the presence of pyridine dicarboxylic acid as a defective linker results in point defects and leads to the formation of CuI sites inside the framework due to charge compensation. Defect-HKUST-1 has been thoroughly characterized using in situ IR spectroscopy, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, and cw EPR spectroscopy.12,13,34,35 The importance of IR spectroscopy and Raman spectroscopy in characterizing DEMOFs is also demonstrated in the literature, which offer in-depth understanding of the types of defects and how they affect MOF characteristics.12,13,34−36

MOF linkers combining neutral 1,2,4-triazole and anionic carboxylate groups offer several benefits: low overall charge, resistance to oxidizing agents, rich coordination chemistry, and various possibilities for functionalization.37−39 Due to these characteristics, MOFs containing these ligands might be valuable in catalysis, gas adsorption, or separation of gases. For example, the coordination polymer [Cu(Me-4py-trz-ia)], (Me-4py-trz-ia2– = 5-(3-methyl-5-(pyridin-4-yl)-4H-1,2,4-triazol-4-yl)isophthalate) is a representative for a family of MOFs for the separation of methane from nitrogen; this MOF also exhibits one of the highest hydrogen uptakes at atmospheric pressure (3.1 wt % at 77 K).40,41 [Cu2(1L)2]42 (1L2– = 5-(3-methyl-4H-1,2,4-triazol-4-yl)isophthalate) belongs to third-generation MOFs with a characteristic ultramicropore system, and this MOF showcased a characteristic dynamic behavior, i.e., guest induced structural change of the host lattice.42,43 [Cu2(1L)2] is reported to adsorb CO2 up to 7.3 mmol/g at 298 K and 3 MPa, and in a prior investigation, it was determined that the pore size distribution (PSD), derived from the crystal structure, exhibits a bimodal pattern with pore sizes of 0.49 and 0.32 nm, whereas at 77 K, no N2 adsorption is observed after activation42; more detailed studies on n-butane sorption in this structurally flexible MOF have been reported recently.43,44

In the following, we report the synthesis of defect-engineered MOFs (DEMOFs) by mixing the regular linker 1L2– with 3-(3-methyl-4H-1,2,4-triazol-4-yl)benzoate37 (2L–) as a “defective” linker. Due to the missing carboxylate group, incorporation of 2L– should generate unoccupied coordination sites in the equatorial position of the Cu2(carboxylate)4 paddle wheel units and should also lead to the preferred formation of CuI sites inside the framework for charge compensation. More sensitive and suitable techniques are needed to gain a deeper knowledge of the local structure and electronic alterations at the defective sites. Such tools are X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy, and X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS).12,45–50,51 For example, studies by Fang et al.,12 Marx et al.,51 and Kjaervik et al.,52 utilized XPS, FT-IR, and XAS measurements to demonstrate the influence of doping in HKUST-1 with the modified linker 2,5-pyridinedicarboxylate (PyDC) in defect-engineered HKUST-1. EPR methods have been shown to be powerful tools for studying the local structure of triazolyl benzoate-based MOFs.45,46 This class of linkers leads to the formation of dinuclear metal ion paddle wheel units that exhibit typical magnetic exchange interactions between CuII atoms; these are primarily explained by the indirect coupling through several ligand orbitals, known as the superexchange path.46 Since the past decades, cw EPR spectroscopy has proven to be a sophisticated tool to probe such magnetic interactions in dinuclear CuII units in MOFs and other types of magnetic materials.45−50 The determination of the isosteric heat of adsorption ΔHads57 is an important method, notably in MOFs, to better verify the creation of coordinatively unsaturated sites13 (CUSs) within the MOF structure. The basic idea is that a larger concentration of these sites causes a rise in the amount of energy gained during adsorption or needed for desorption.61 These investigations demonstrate a relationship between ΔHads and the concentration of CUSs. This relationship has important ramifications since it allows us to quantitatively evaluate the distribution of coordinatively unsaturated sites within MOFs, providing important information about their structural characteristics and possible uses. Therefore, we explore in detail the magnetostructural properties by cw EPR, local sites by XPS, and CUSs by determination of ΔHads. This research contributes to advancing the understanding and utilization of defect-engineered MOFs in various applications.

Experimental Description

Synthesis of the Defect-Engineered MOFs

Synthesis of the linkers H2(Me-trz-ia) (H21L) and H(Me-trz-mba) (H2L) as well as the DEMOFs synthesis were performed according to Kobalz et al.42 Details are reported in the Supporting Information (SI, Sections S2 and Section S3). For synthesis of the DEMOFs we modified the procedure by replacing up to 24% (in the reaction mixture) of the regular linker H21L by the defective linker H2L while keeping the molar ratio CuII: ligand = 1:1 constant (Scheme 1 and SI, Table S1). After synthesis, the samples were thoroughly washed with DMF:EtOH (1:1) followed by solvent exchange for 7 days. During this time MeOH was replaced regularly every 6 h. With an increasing percentage of H2L, a slight color change of the resulting DEMOF from green to bluish-green is observed (SI, Figure S1). After solvent exchange, the samples were kept under MeOH inside a sealed vial for further analysis. Samples without any defective linker are referred to as ″ReMOF″ (regular MOF) while samples with a defective linker are named based on the actual percentage of defective linker incorporated. For instance, a sample [Cu2(1L1–x2Lx)2] containing 2.9% defective linker (x = 0.029), obtained from HPLC analysis, is labeled as ″DEMOF_2.9%″.

Scheme 1. The Strategy Implemented for the Development of DEMOFs is Based on Partial Replacement of the Regular Linker 1L2– by the “Defective Linker” 2L– Lacking One Carboxylate Group.

The diagram focuses on Cu–Cu paddlewheel unit changes due to 2L– incorporation. Color coding: CuI, brown; CuII, turquoise; C, gray; O, red; and N, blue. Additional structural specifics are excluded for the sake of simplicity.

Results and Discussion

Solvothermal synthesis of [Cu2(1L1–x2Lx)2] was achieved by using CuCl2·2H2O, H21L, and H2L at different molar ratios while keeping the copper salt amount fixed.

PXRD Analysis

The powder XRD patterns of DEMOF_2.9% and DEMOF_7.0% are in good agreement with the simulated patterns originating from single crystal data of ReMOF [Cu2(1L)2],42 and no extra phases are detected (Figure 1). The diffraction patterns also show that the parent MOF structure is retained with incorporated 2L– up to certain limits (less than 8%). With an increasing percentage of 2L– in the DEMOF, we observe a decrease in intensity as well as broadening of the peaks; the peak around 2Θ = 9.2° becomes broader and several reflections disappear with a higher percentage of 2L–. This is expected due to the formation of defects based on structural irregularities inside the DEMOF. A concentration of 2L– higher than 8% leads to the formation of an amorphous product, suggesting that the DEMOF system does not feature a mixture of MOF phases consisting of ReMOF and an additional compound containing the defective linker 2L–. Instead, up to the 2L– concentration in DEMOF_7.0%, we observe a crystalline product through PXRD analysis, confirming that the DEMOF samples can incorporate 2L– alongside the regular linker 1L2–.

Figure 1.

PXRD pattern (r.t., Cu–Kα1 radiation) of solvent-exchanged ReMOF and DEMOF samples. The simulated pattern is based on single crystal data measured at 180 K.42

The microstrain broadening53 in the PXRD patterns of DEMOFs shows a positive correlation with an increasing percentage of 2L– in DEMOF samples; details are reported in the SI (Section S5.2, Figure S6). This empirical evidence supports the presence of internal defects in the DEMOF samples.

FTIR and Raman Spectroscopy

FTIR and Raman spectra were obtained after sample activation (Figure 2a,b). Comparative analysis of the FTIR spectra between the ReMOF and DEMOF revealed minor differences attributed to the absence of a carboxylate group in the 2L– linker. We observed a small red-shift in DEMOF_7.0% as compared to the ReMOF. The complete spectra with assignments are available in the SI (Section S6 and Figure S10). These findings suggest that the incorporation of 2L– introduces defects, leading to the observed broadening as well as the lowering of wavenumbers in the IR spectra. A similar broadening and red-shift are also reported by Fang et al.12 in their work on defect-engineered HKUST-1 using a mixed linker approach.

Figure 2.

(a) FTIR spectra of ReMOF and DEMOF samples (δ: bending, νsym: symmetric stretching, νasym: antisymmetric stretching, τ: twisting) and (b) Raman spectra of ReMOF and DEMOF samples with vibrational frequency assignments.

The peak assignments in the Raman spectra are included in Figure 2b and the SI (Section S7). Similar to the IR spectra, there is a broadening of the Raman signals of the DEMOFs. We can assign the signal between 190 and 270 cm–1 to the Cu–Cu dimer stretching mode,36 which is an IR-inactive vibration mode. Again, the spectra of the ReMOF and DEMOFs demonstrate notable broadening and reduced intensity in the stretching vibration, accompanied by a slight red shift. These observed effects resemble the well-documented phenomena observed in various inorganic materials.54−56 Therefore, we attribute these changes to defects in the paddle wheel unit of the MOFs due to the incorporation of the defective linker 2L–.

Determination of the Amount of Incorporated Defective Linker 2L– in [Cu2(1L1–x2Lx)2]

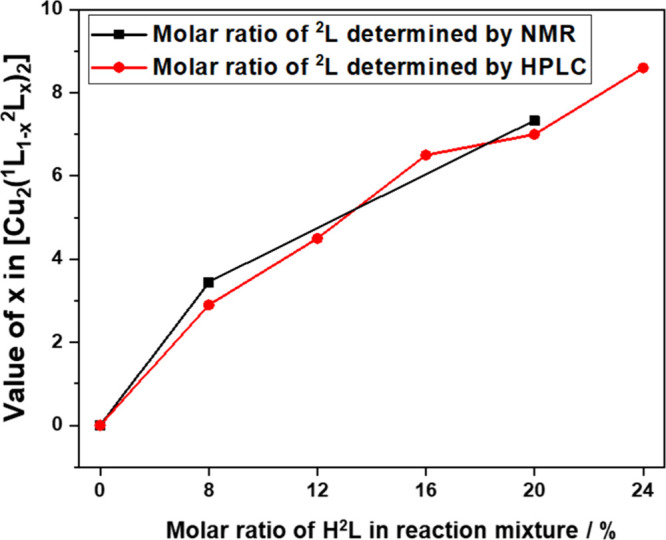

The amount of linker 2L– incorporated in the DEMOFs [Cu2(1L(1–x)2Lx)2] was determined by digestion of the synthesized MOFs in NaOH/D2O (SI, Section S8) and subsequent analysis by 1H NMR spectroscopy and HPLC (SI, Section S9). In the 1H NMR spectra of the DEMOF samples after digestion, slight differences in the chemical shift of protons of 2L–compared to the regular linker 1L2– (SI, Section S8) are due to a different chemical environment. Slight changes in chemical shifts also occurred in comparison to the spectra of pure carboxylic acids H21L and H2L after deprotonation in the basic digestion medium. The fraction of 2L– within the DEMOF depends on the feeding ratio H2L/H21L + H2L in the synthesis as documented in Figure 3 and the SI (Section S8, Table S2 and Section S9, Table S3).

Figure 3.

Molar ratio x = 1L2–/(1L2– + 2L–) in the [Cu2(1L(1–x)2Lx)2] DEMOF as determined by integration of 1H NMR signals (black) and by HPLC (red) vs H2L/(H21L + H2L) in the reaction mixture for synthesis.

The findings presented herein demonstrate the capacity to finely modulate the incorporation of 2L– through deliberate adjustments in the feeding ratio. The quantity of 2L– encompassed within the framework is lower than the initial amount introduced in the reaction mixture, and the molar ratio increases almost linearly with respect to the linker ratio during synthesis (Figure 3). Even though 1H NMR spectroscopy is a reliable method for discerning defective linkers, there are certain limitations such as overlapping peaks, changes in chemical shift, and the influence of possible remaining paramagnetic Cu2+ ions (SI, Section S8). As a complementary method of quantification, we employed high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to precisely quantify the percentage of 2L– incorporated into the DEMOF samples. More details about sample preparation and the mobile phase are provided in the SI (Section S9, Table S3). The quantifications based on 1H NMR and HPLC analysis are compared in Figure 3, and these results are in agreement within a deviation of ±0.5%. The percentage of 2L– in the DEMOFs is included in their denominations as DEMOF_2.9% and DEMOF_7.0%.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

To gain quantitative information about the presence of Cu atoms in different oxidation states, CuI and CuII, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy was applied on ReMOF and DEMOF samples. Deconvoluted XPS spectra, binding energies, and the full assignments of the XPS spectra are described in detail in the SI (Section S11, Table S4). The Cu 2p3/2 peaks at 935.1 and 933.2 eV are attributed to CuII and CuI, respectively (Figure 4). A CuI peak at 933.2 eV is already present in the ReMOF. Notably, Fang et al.12 assigned the peak around 933.2 eV to CuI–CuII units formed due to CuII reduction to CuI in paddle wheel structures (defective paddle wheel unit) and the peak at 935.1 eV to regular CuII–CuII paddle units without defects. The XPS spectra clearly show an increasing increment of the area within the shoulder peak of CuI from the ReMOF to DEMOF_7.0%, which implies increasing defect concentration as well as heterogeneity in the DEMOF due to defective linker incorporation. Our results of the estimated increment of CuI agree well with the analysis of DEMOFs, as reported in the literature.12,13 The presence of two different types of paddle wheel units is also supported by broad Cu LMM Auger spectra, which exhibit signals around 916.5 eV,12,58−60 assigned to defective paddle wheels CuI–CuII, and 918.2 eV for regular CuII–CuII paddle wheels (SI, Section S11.1, Figures S16 and S17). The XPS spectra provide characteristic peaks corresponding to both CuI and CuII oxidation states. Although the relative ratios of these peaks can be used to quantify the abundance of CuI from defective paddle wheel units within the MOF, the quantifications may have some uncertainty due to X-ray-induced degradation of CuII species or due to the surface charge effect.52 CuI species might be formed already during synthesis or in the activation process where ethanol might serve as the reducing agent.12,52 As the incorporation of defective linkers 2L– with a missing carboxylate group increases, the number of CuI defective paddle wheel units also increases. Consequently, the proportion of coordinatively unsaturated sites (CUSs) within the MOF structure is also assumed to increase. Peak broadening and small shifts in the positions of the peaks indicate the presence of different oxidation states or a change in coordination environments of the copper ions associated with the defect sites. We notice a drastic increase in the CuI population from the ReMOF to DEMOF_2.9%; however, the changes to DEMOF_7.0% are not significant (Figure 4). The relative abundance of defect sites, estimated by the relative intensities of the peaks associated with different oxidation states, is summarized in Table 1. These values might be biased by the surface sensitivity of XPS, which may not effectively reveal alterations occurring below the surface or within the bulk of the DEMOFs. To address the limitations of XPS in analyzing these subsurface changes, we utilized cw EPR, a potent characterization technique. This method enables a more thorough investigation of such defective sites, which are discussed in the subsequent section.

Figure 4.

Cu 2p3/2 XPS spectra of the ReMOF and DEMOF samples. The line shape analysis and copper species quantification were performed using CASA XPS software.62

Table 1. XPS Analysis for the Relative Quantification of CuII and CuI in ReMOF and DEMOF Samples.

| sample | oxidation state | percentage |

|---|---|---|

| ReMOF | CuII | 83.5% |

| CuI | 16.5% | |

| DEMOF_2.9% | CuII | 73.4% |

| CuI | 26.6% | |

| DEMOF_7.0% | CuII | 73.8% |

| CuI | 26.2% |

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR)

The X-band cw EPR spectra of the ReMOF [Cu2(1L)2] were measured by using powder samples suspended in methanol. The spectrum recorded at 160 K is provided in Figure 5, which consists of a superposition of the CuII–CuII paddle wheel signal (species A) and the signal of uncoupled CuII species (B). Species A can be interpreted as two S = 1/2 spins from the interconnected CuII–CuII dinuclear unit, resulting in antiferromagnetic coupling with S = 0 as the ground state level (diamagnetic) and S = 1 as the paramagnetic excited state level (triplet state). This triplet state (S = 1) is thermally populated above 60 K and gets more pronounced at higher temperatures, as observed in the temperature-dependent spectra obtained using cw X-band and Q-band EPR (SI, Section S12, Figure S18). The spectral simulation for the anisotropic S = 1 system can be described by the following Hamiltonian 1):

| 1 |

where βe denotes

Bohr’s magneton and  denotes the CuII–CuII pair g-tensor. B0 is the external magnetic field. Both D (axial)

and E (orthorhombic) represent zero field splitting

(zfs) parameters, where the zfs tensor and

denotes the CuII–CuII pair g-tensor. B0 is the external magnetic field. Both D (axial)

and E (orthorhombic) represent zero field splitting

(zfs) parameters, where the zfs tensor and  tensor are assumed to be coaxial.

tensor are assumed to be coaxial.  is the electron spin operator with S = 1. The axially symmetric system (D ≠

0 and E = 0) has four expected transitions: Bx1,y1, Bx2,y2, Bz1, and Bz2, which

can be clearly resolved at the Q-band (Figure S19). In the X-band frequency (9.4 GHz) at low magnetic fields

(<150 mT), the Bx1, y1 and Bz1 transitions are superimposed with the signal

of a forbidden transition (Δms =

±2 with the magnetic spin quantum number ms) owing to the comparable magnitude of D and

the microwave quantum frequency (Figure 5).

is the electron spin operator with S = 1. The axially symmetric system (D ≠

0 and E = 0) has four expected transitions: Bx1,y1, Bx2,y2, Bz1, and Bz2, which

can be clearly resolved at the Q-band (Figure S19). In the X-band frequency (9.4 GHz) at low magnetic fields

(<150 mT), the Bx1, y1 and Bz1 transitions are superimposed with the signal

of a forbidden transition (Δms =

±2 with the magnetic spin quantum number ms) owing to the comparable magnitude of D and

the microwave quantum frequency (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

X-band cw EPR spectra of the ReMOF [Cu2(1L)2] measured at 160 K and its spectral simulation of [Cu2(1L)2] by considering contributions of two different species, species A with S = 1 and species B with S = 1/2.

On the other hand, Q-band cw EPR provides a relatively more resolved spectral pattern as compared to the X-band since Bx1, y1 and Bz1 are separated from the typical forbidden transition (Δms = ±2) signal around 500 mT (SI, Section S12, Figure S19). The fine structure pattern can be simulated using gxx,yy = 2.07, gzz = 2.38, D = 0.367 cm–1, and E ≈ 0 if we consider that g- and D- tensors are collinear. Those parameters are in good agreement with other compounds containing Cu2 paddle wheel units.46,50 The D parameters for the ReMOF and DEMOFs (Table 2) are also quite similar to each other, also implying comparable structures of the Cu2 paddle wheels.

Table 2. Comparison of Defect Ratio and Zero Field Splitting Parameters for ReMOF and DEMOF Samples, as Determined from the EPR Spectra.

| species | NM/NPW | J (cm–1) | D (cm–1) | D strain (cm–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ReMOF | 0.12(2) | –252(30) | 0.37(1) | 0.030(5) |

| DEMOF_2.9% | 0.29(2) | –200(30) | 0.37(1) | 0.030(5) |

| DEMOF_7.0% | 0.33(2) | –220(30) | 0.36(1) | 0.040(5) |

Temperature-dependent X-band and Q-band cw EPR spectra can only be applicable up to the freezing point of methanol at 175 K since beyond that temperature, the measurement is affected by a low S/N ratio. The cw EPR temperature-dependent data set is very useful for estimating the isotropic exchange coupling constant (J) of the antiferromagnetically coupled CuII–CuII pairs using the Bleaney–Bowers equation (eq 2).63

| 2 |

where μ0 = 4π·10–7 T·m·A–1 is the permeability of vacuum, g is an average of the principle values of the g-tensor, βe is the Bohr magneton, and J is the isotropic exchange coupling. One can consider that the magnetic susceptibility (χ) is proportional to the intensity of the S = 1 spectrum. As the line width of the Bx2,y2 transition is temperature-independent, we used its signal amplitude as a measure for the relative EPR intensity, IEPR, of the S = 1 paddle wheel signal. The exchange coupling J is obtained by fitting the experimental temperature-dependent IEPR data with eq 2. The estimated J values for the ReMOF and DEMOF do not differ significantly, ranging from −250 cm–1 for the ReMOF to −200 and −220 cm–1 for DEMOF_2.9% and DEMOF_7.0%, respectively (Figure S18). The negative sign of J indicates that the antiferromagnetic interaction of the Cu2 paddle wheels is still preserved in DEMOF samples.

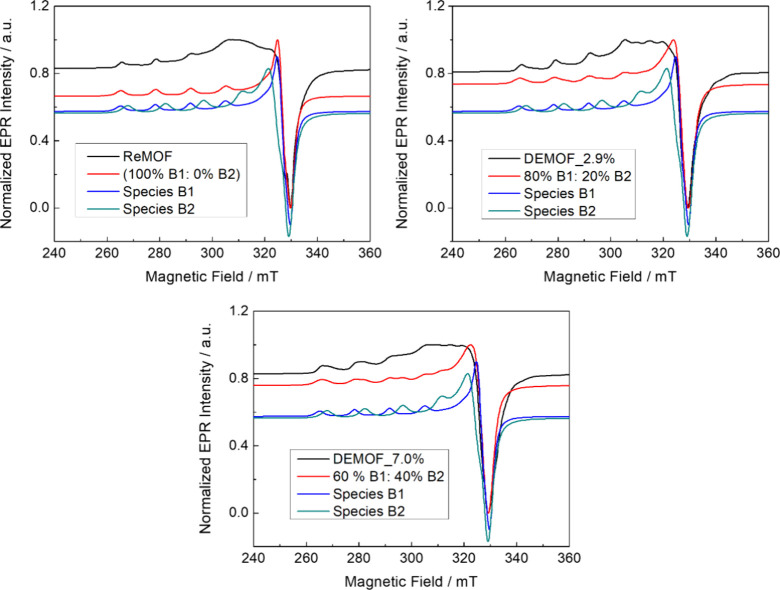

The uncoupled CuII species B shows the typical anisotropic EPR powder pattern of an electron spin S = 1/2 coupled to a nuclear spin of Cu (I = 3/2) showing up in low-temperature spectra recorded at 10 K as four resolved hyperfine lines at gzz (B0 = 270–300 mT) (Figure 6). A complete set of g and A values obtained by Easyspin64 simulation is given in Table 3. As displayed in Figure 6, two uncoupled CuII species B1 and B2 with slightly different parameters are observed at 10 K. Species B1 can be used to describe the uncoupled CuII for the ReMOF sample, exhibiting a gzz value of 2.36, while the hyperfine coupling Azz is accounted for 430 MHz. We can see a clear trend of the B2 species increasing as the amount of defective linker also increases from the spectral simulation results. The B2 species has slightly different EPR parameters: a gzz of 2.32 and Azz of 460 MHz. For both B1 and B2, the spectral parameters are similar to those in literature reports on CuII compounds with a square pyramidal oxygen environment; the differences might be due to a slightly different charge delocalization.48−50

Figure 6.

X-band cw EPR spectra of the S = 1/2 section (uncoupled CuII species) of the [Cu2(1L1–x2Lx)2] MOF series measured at 10 K. The simulated spectrum in red is the total contribution of B1 and B2 species with the corresponding weight provided in the small insets.

Table 3. Spin Hamiltonian Parameters of Mononuclear Cu2+ Ions in [Cu2(1L)2] ReMOF Samples Determined by Spectral Simulations of the Experimental EPR Spectra at 10 K Using Easyspin Software64.

| species | gxx,yy | gzz | Axx,yy (MHz) | Azz (MHz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | 2.06(5) | 2.36(4) | 50(20) | 430(20) |

| B2 | 2.06(5) | 2.32(4) | 50(20) | 460(20) |

To verify the effect of defective linker introduction toward the properties of the MOFs, Figure 7 provides the spectral comparison of DEMOF samples with different amounts of defective linker 2L–. The spectral pattern at the X-band (Figure 7) changes significantly when the defective linker is incorporated. Obviously, the relative intensity of the EPR signals of species B1 and B2 with respect to signal A of the antiferromagnetically coupled CuII–CuII paddle wheels increases with the increasing amount of defective linker. Taking further into account the square pyramidal coordination geometry of the CuII ion species belonging to signal B1, it is justified to assign these signals to a paramagnetic CuII–CuI paddle wheel unit, which is a result of partial reduction of CuII–CuII to CuII–CuI due to 2L– incorporation. In other words, species B2 can be regarded as coordinatively unsaturated sites (CUSs).

Figure 7.

EPR spectra of the ReMOF (pink) in comparison to DEMOF_2.9% (orange) and DEMOF_7.0% (blue) recorded at X-band frequency and T = 160 K. All spectra were normalized to the intensity of species A for better comparison. The inset shows the comparison of signal intensities of the noncoupled CuII (B1, B2) from the abovementioned samples.

Assuming that the EPR signal intensity is proportional to the magnetic susceptibility χ and negligible differences are expected between g-values for both Cu species within the Cu2 paddle wheels, the intensity ratio of the signals of the noncoupled CuII species IM and that of the paddle wheel unit IPW can be estimated by fitting the weight (contribution) for each individual species, i.e., noncoupled CuII species (IM) and Cu2 paddle wheels (IPW), to the overall spectral simulation of the experimental spectra at 160 K. The spectral simulation for the ReMOF is given in Figure 5, whereas those for DEMOF_2.9% and DEMOF_7.0% are presented in the SI (Section S12, Figure S20). Thus, the ratio NM/NPW can be extracted using eq 3.50 Note that J is an isotropic exchange coupling constant taken from the temperature-dependent data provided in the SI (Section S12, Figure S18).

| 3 |

The ratio NM/NPW is interpreted as the number of mononuclear CuII units with respect to Cu2 paddle wheel units. For the ReMOF, we found a ratio NM/NPW around 0.12 (Table 2). This value is similar to those of some other Cu2 paddle wheel-based MOFs.46,47,50

Moreover, the ratio of defects is strikingly increased to 0.29 for DEMOF_2.9% (Figure 7). This implies that even a low percentage of defective linkers would impart a significant amount of defective sites. However, the ratio NM/NPW for DEMOF_7.0% only enhanced slightly to 0.33 if compared to DEMOF_2.9%.

In general, we conclude that the trend of NM/NPW ratio supports our assumption that the origin of the defect sites most probably stems from the structural defect, CuI–CuII (defined as species B2 in Figure 6), which is promoted as a consequence of the charge compensation, which takes place with the incorporation of the defective linker 2L– with one missing carboxylate group. These NM/NPW ratios correlate well with the defect ratio determined by XPS analysis, taking into account the limitations because of surface sensitivity, and with the microstrain broadening observed by PXRD (SI, Section 5.2, Figure S6).

H2 Gas Adsorption and Isosteric Heat of Adsorption

Understanding the strength of the interaction between adsorbate–absorbent (MOF) pairs requires knowledge of the isosteric heat of adsorption ΔHads.57 It is also known that defects in MOFs as modified sites may alter the adsorption behavior.9,65 For the determination of ΔHads for H2 adsorption on both regular and defect-engineered materials, we conducted hydrogen physisorption experiments at three different temperatures, 67, 77, and 87 K. The observed hysteresis between adsorption and desorption branches of the isotherm could be interpreted as a sign of kinetically hindered adsorption in the ultramicropores.66 This is clearly reflected in the pressure profile (SI, Section S13, Figure S21) recorded during the adsorption and desorption branches. A long duration is needed for the equilibration in the adsorption process in the magnitude of 1 h for DEMOF_7.0% due to kinetic hindrance (SI, Figure S21). The slow adsorption kinetics at low temperatures originates from the narrow pore diameters and is more noticeable in ultramicroporous MOFs66 as a result of a kinetic convergency, molecular transport, and pore structure limitations. In contrast, the desorption process proceeds significantly faster. Therefore, similar to Weinrauch et al.,10 we used the desorption branch for the calculation of the isosteric heat of adsorption for hydrogen in the temperature range 67–87 K; see the SI (Section S13, Figure S23–S25) to understand the effects of defects. For the ReMOF, characterized by the lowest defect concentration, the desorption enthalpy spans from 8.7 kJ/mol (at a low uptake of 0.1 mmol/g) to 6.4 kJ/mol. On the contrary, DEMOF_2.9% exhibits a desorption enthalpy ranging from 11.1 to 4.5 kJ/mol. This rise in ΔHads at a low loading is attributed to CUS and CuI site formation through 2L– incorporation. Compared to both the ReMOF and DEMOF_2.9%, DEMOF_7.0%, which features a higher concentration of the monoanionic linker 2L–, demonstrates even higher energies ranging from 14.8 kJ/mol at a low uptake to 4.0 kJ/mol at the higher uptake limit. This significant difference between the ReMOF and DEMOF_7.0% in the ΔHads parameter at the lower uptake range and the decrease with increasing H2 loading are shown in Figure 8. It can be interpreted that the adsorption of H2 takes place preferably on strong adsorption sites, which have been seen in many MOFs with coordinatively unsaturated open metal sites, and the subsequent adsorption occurs predominantly within the pores with lower adsorption/desorption enthalpy.67 According to this result, increasing the concentration of 2L– leads to a higher concentration of structural defects, and these sites have stronger interactions toward the adsorbate. Various MOFs exhibit similar effects: Thomas et al.68 observed an enhanced interaction between H2 and Cu centers in an ultramicroporous MOF, leading to a high ΔHads for H2 adsorption of 12.3 kJ/mol. Likewise, synthesized derivatives of M-MOF-74 (M = Ni, Co, Fe, Mn, and Mg) with enhanced charge density in open metal sites, result in higher H2 binding enthalpies than M-MOF-74.61 For instance, Ni2(m-dobdc) and Co2(m-dobdc) had 12.3 and 11.5 kJ/mol, respectively, surpassing Ni2(dobdc) (11.9 kJ/mol) and Co2(dobdc) (10.8 kJ/mol).61 Notably, some cases with extraordinarily high ΔHads are reported, e.g., for CuI-MFU-4l (32 kJ/mol) and V2Cl2.8(btdd) (21 kJ/mol).10,61 Therefore, the positive correlation can be directly evidenced by the introduction of CUSs, which is also supported by XPS and EPR studies in this work. These structural alterations, mainly stemming from defects, enhance the interactions between adsorbate molecules and the DEMOF.

Figure 8.

ΔHads obtained using Freundlich–Langmuir fits and Clausius–Clapeyron equation to the H2 desorption isotherms on ReMOF and DEMOF samples at 67, 77, and 87 K.

In contrast, H2 adsorption experiments at 24 K showed that DEMOF_2.9% and DEMOF_7.0% adsorb significantly less hydrogen compared to their performance at 77 K. This loss of adsorption capacity could be attributed to reduced vibrations of the pore apertures at those low temperatures. With a more rigid aperture in the size of the H2 molecule, the guest molecules cannot enter the pores, as detailed in the SI (Section S13, Figure S29). This phenomenon has been observed in microporous MOF Mn(HCOO)269 and particularly the findings by Oh et al.70 on Py@COF-1. COF-1 with incorporated pyridine shows a similar phenomenon. This behavior was explained as a unique temperature-activated gating mechanism that operates independent of structural alterations within the material’s framework. Instead, the gating effect is attributed to either a dynamic enlargement of the pore openings or the acquisition of sufficient kinetic energy by adsorbed molecules. This observation suggests that access to the pore is a direct consequence of thermal energy influencing the material’s behavior or the mobility of the molecules within.69 At higher temperatures, the vibrations allow passage of H2 molecules; thus, the gating behavior is controlled by the temperature through lattice vibrations, in contrast to gate-opening/closing behavior as observed, e.g., in MIL-53-type MOFs. If we compare our studies with Py@COF-1, the ReMOF, with less structural defects, permits hydrogen access at 24 K, showing a similarity to the inherently open structure of COF-1. On the other hand, DEMOF_7.0%, with its higher concentration of defects, mirrors Py@COF-1 behavior by selectively blocking hydrogen access at 24 K, a feature attributed to its more compact structure. Hence incorporation of 2L– in the ReMOF, like the strategic inclusion of pyridine in parent COF-1, alters the MOF internal structure, leading to hindered gas diffusion. This parallel suggests that the presence and nature of defective linkers within MOFs can drastically influence gas adsorption by modifying the physical structure and affecting diffusion kinetics.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the comprehensive analysis of DEMOF samples through XRD, EPR, XPS, and hydrogen adsorption, including determination of the isosteric heat of adsorption ΔHads, elucidates the influence of defective linker incorporation in the MOF structure of [Cu2(1L)2] (1L2– = 5-(3-methyl-4H-1,2,4-triazol-4-yl)isophthalate). The amount of incorporated linker 2L– of 2.9% and 7.0% in DEMOFs [Cu2(1L1–x2Lx)2] was quantitatively determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy and HPLC, showing the progressive increase in defective linker (2L–) concentration with increasing percentage of H2L during synthesis. The powder XRD patterns of DEMOF samples align well with the simulated pattern; with an increasing concentration of 2L–, intensity reduction and peak broadening are observed. FTIR and Raman analysis also support the qualitative aspects of defects with characteristic peak broadening with an increasing amount of 2L–. These are attributed to the formation of defects and irregularities within the DEMOFs, in agreement with increasing microstrain broadening detected in the PXRD patterns. A collapse of the crystalline framework is observed once the 2L– concentration exceeds a certain threshold, leading to the formation of amorphous products.

According to XPS and EPR studies, the incorporation of the “defective linker” 2L– with a missing carboxylate group in respect to the “regular linker” 1L2– induces coordinatively unsaturated sites (CUSs). XPS analysis reveals the emergence of CuI–CuII defective paddle wheel units, identified by distinct peaks in the spectra. While a consistent proportion of CuI is observed from the ReMOF to DEMOF_2.9%, due to surface sensitivity, XPS analysis is unable to detect significant changes in the defect structures at higher concentrations, such as in DEMOF_7.0%. In contrast, cw EPR X-band studies delve deeper into the defect dynamics, highlighting two specific species of CuII defects, termed B1 and B2. The intensity and prevalence of species B2, which represents coordinatively unsaturated sites resulting from a partial reduction from CuII–CuII to CuII–CuI, increase with the addition of defective linkers. Therefore, while XPS effectively confirms the presence of CuI and CuII, EPR completes these studies by offering detailed insights into the bulk structural changes associated with these defects. The investigation of isosteric heat of adsorption provides a quantitative understanding of defect-driven changes, and the CO2 adsorption reveals enhanced porosity in the DEMOF systems. Eventually, the incorporation of defective linkers and CUSs results in enhanced interactions between adsorbate molecules and DEMOFs.

Thus, the collective evidence suggests that the mixed linker approach leads to the formation of defects, which in turn enhance adsorption interactions. These findings provide valuable insights for tailoring the MOF properties through controlled defect engineering.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Dr. Berthold Kersting for FTIR analysis, Anish Das for Raman analysis, and Mrs. Manuela Roßberg, Dr. Maik Icker, and Mrs. Heike Rudzik for elemental, NMR, and ICP-OES analyses. The authors thank Kavipriya Thangavel for Q-band EPR measurements and data analysis.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.4c01589.

Analytical, spectroscopic, and other characterization data including chemicals, ligand synthesis, defect-engineered MOF synthesis, single crystal information, PXRD patterns and Pawley refinement, strain analysis, TGA, FTIR and Raman spectra,1H NMR, HPLC, XPS, cw EPR, H2 and CO2 gas sorption isotherms, isosteric heat of adsorption, SEM images, and elemental analysis data (PDF)

Author Present Address

△ Academy of Scientific and Innovative Research (AcSIR), Ghaziabad 201 002, India

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) for funding GRK 2721: “Hydrogen Isotopes 123H” (Project IDs 443871192, 448298270). The IR spectrometer was funded by DFG project number 448298270.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Janiak C.; Vieth J. K. MOFs, MILs and More: Concepts, Properties and Applications for Porous Coordination Networks (PCNs). New J. Chem. 2010, 34, 2366–2388. 10.1039/c0nj00275e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyndon R.; Konstas K.; Ladewig B. P.; Southon P. D.; Kepert P. C. J.; Hill M. R. Dynamic Photo-Switching in Metal-Organic Frameworks as a Route to Low-Energy Carbon Dioxide Capture and Release. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52 (13), 3695–3698. 10.1002/anie.201206359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann M.; Kunz S.; Himsl D.; Tangermann O.; Ernst S.; Wagener A. Adsorptive Separation of Isobutene and Isobutane on Cu3(BTC)2. Langmuir 2008, 24 (16), 8634–8642. 10.1021/la8008656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer C. A.; Timofeeva T. V.; Settersten T. B.; Patterson B. D.; Liu V. H.; Simmons B. A.; Allendorf M. D. Influence of Connectivity and Porosity on Ligand-Based Luminescence in Zinc Metal-Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129 (22), 7136–7144. 10.1021/ja0700395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsianos A.; Kazimierska E.; Barron A. R.; Taddei M.; Andreoli E. A New Approach to Enhancing the CO2 Capture Performance of Defective UiO-66: Via Post-Synthetic Defect Exchange. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48 (10), 3349–3359. 10.1039/C9DT00154A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A. W.; Babarao R.; Jain A.; Trousselet F.; Coudert F. X. Defects in Metal-Organic Frameworks: A Compromise between Adsorption and Stability?. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45 (10), 4352–4359. 10.1039/C5DT04330A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang W.; Zhang Y.; Chen Y.; Liu C. J.; Tu X. Synthesis, Characterization and Application of Defective Metal-Organic Frameworks: Current Status and Perspectives. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 21526–21546. 10.1039/D0TA08009H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montoro C.; Ocón P.; Zamora F.; Navarro J. A. R. Metal-Organic Frameworks Containing Missing-Linker Defects Leading to High Hydroxide-Ion Conductivity. Chem.—Eur. J. 2016, 22 (5), 1646–1651. 10.1002/chem.201503951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H.; Chua Y. S.; Krungleviciute V.; Tyagi M.; Chen P.; Yildirim T.; Zhou W. Unusual and Highly Tunable Missing-Linker Defects in Zirconium Metal-Organic Framework UiO-66 and Their Important Effects on Gas Adsorption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135 (28), 10525–10532. 10.1021/ja404514r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinrauch I.; Savchenko I.; Denysenko D.; Souliou S. M.; Kim H.-H.; Le Tacon M.; Daemen L. L.; Cheng Y.; Mavrandonakis A.; Ramirez-Cuesta A. J.; Volkmer D.; Schütz G.; Hirscher M.; Heine T. Capture of Heavy Hydrogen Isotopes in a Metal-Organic Framework with Active Cu(I) Sites. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14496. 10.1038/ncomms14496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Wang W.; Fan Z.; Chen S.; Nefedov A.; Heißler S.; Fischer R. A.; Wöll C.; Wang Y. Defect-Engineered Metal-Organic Frameworks: A Thorough Characterization of Active Sites Using CO as a Probe Molecule. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125 (1), 593–601. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.0c09738. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Z.; Dürholt J. P.; Kauer M.; Zhang W.; Lochenie C.; Jee B.; Albada B.; Metzler-Nolte N.; Pöppl A.; Weber B.; Muhler M.; Wang Y.; Schmid R.; Fischer R. A. Structural Complexity in Metal-Organic Frameworks: Simultaneous Modification of Open Metal Sites and Hierarchical Porosity by Systematic Doping with Defective Linkers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136 (27), 9627–9636. 10.1021/ja503218j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Petkov P.; Vayssilov G. N.; Liu J.; Shekhah O.; Wang Y.; Wöll C.; Heine T. Defects in MOFs: A Thorough Characterization. ChemPhysChem 2012, 13 (8), 2025–2029. 10.1002/cphc.201200222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei M.; Schukraft G. M.; Warwick M. E. A.; Tiana D.; McPherson M. J.; Jones D. R.; Petit C. Band Gap Modulation in Zirconium-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks by Defect Engineering. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7 (41), 23781–23786. 10.1039/C9TA05216J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Svane K. L.; Bristow J. K.; Gale J. D.; Walsh A. Vacancy Defect Configurations in the Metal-Organic Framework UiO-66: Energetics and Electronic Structure. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 8507–8513. 10.1039/C7TA11155J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vos A.; Hendrickx K.; Van Der Voort P.; Van Speybroeck V.; Lejaeghere K. Missing Linkers: An Alternative Pathway to UiO-66 Electronic Structure Engineering. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29 (7), 3006–3019. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b05444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoro C.; Ocón P.; Zamora F.; Navarro J. A. R. Metal-Organic Frameworks Containing Missing-Linker Defects Leading to High Hydroxide-Ion Conductivity. Chem.—Eur. J. 2016, 22 (5), 1646–1651. 10.1002/chem.201503951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.; Guo X.; Geng P.; Du M.; Jing Q.; Chen X.; Zhang G.; Li H.; Xu Q.; Braunstein P.; Pang H. Rational Design and General Synthesis of Multimetallic Metal–Organic Framework Nano-Octahedra for Enhanced Li–S Battery. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2105163 10.1002/adma.202105163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C.; Ferreiro-Rangel C. A.; Fischer M.; Gomes J. R. B.; Jorge M. A Transferable Model for Adsorption in Mofs with Unsaturated Metal Sites. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121 (1), 441–458. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b10751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dissegna S.; Vervoorts P.; Hobday C. L.; Düren T.; Daisenberger D.; Smith A. J.; Fischer R. A.; Kieslich G. Tuning the Mechanical Response of Metal-Organic Frameworks by Defect Engineering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (37), 11581–11584. 10.1021/jacs.8b07098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caratelli C.; Hajek J.; Cirujano F. G.; Waroquier M.; Llabrés i Xamena F. X.; Van Speybroeck V. Nature of Active Sites on UiO-66 and Beneficial Influence of Water in the Catalysis of Fischer Esterification. J. Catal. 2017, 352, 401–414. 10.1016/j.jcat.2017.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y.; Chen Q.; Jiang M.; Yao J. Tailoring the Properties of UiO-66 through Defect Engineering: A Review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 17646–17659. 10.1021/acs.iecr.9b03188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J.; Ledwaba M.; Musyoka N. M.; Langmi H. W.; Mathe M.; Liao S.; Pang W. Structural Defects in Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs): Formation, Detection and Control towards Practices of Interests. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 349, 169–197. 10.1016/j.ccr.2017.08.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei M. When Defects Turn into Virtues: The Curious Case of Zirconium-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 343, 1–24. 10.1016/j.ccr.2017.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Z.; Bueken B.; De Vos D. E.; Fischer R. A. Defect-Engineered Metal–Organic Frameworks. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54 (25), 7234–7254. 10.1002/anie.201411540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravon U.; Savonnet M.; Aguado S.; Domine M. E.; Janneau E.; Farrusseng D. Engineering of Coordination Polymers for Shape Selective Alkylation of Large Aromatics and the Role of Defects. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2010, 129 (3), 319–329. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2009.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cliffe M. J.; Wan W.; Zou X.; Chater P. A.; Kleppe A. K.; Tucker M. G.; Wilhelm H.; Funnell N. P.; Coudert F. X.; Goodwin A. L. Correlated Defect Nanoregions in a Metal-Organic Framework. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4176. 10.1038/ncomms5176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang W.; Zhang Y.; Chen Y.; Liu C. J.; Tu X. Synthesis, Characterization and Application of Defective Metal-Organic Frameworks: Current Status and Perspectives. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 21526–21546. 10.1039/D0TA08009H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shan Y.; Zhang G.; Shi Y.; Pang H. Synthesis and Catalytic Application of Defective MOF Materials. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101301 10.1016/j.xcrp.2023.101301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sholl D. S.; Lively R. P. Defects in Metal–Organic Frameworks: Challenge or Opportunity?. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6 (17), 3437–3444. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b01135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Z.; Bueken B.; De Vos D. E.; Fischer R. A. Defect-Engineered Metal–Organic Frameworks. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54 (25), 7234–7254. 10.1002/anie.201411540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dissegna S.; Epp K.; Heinz W. R.; Kieslich G.; Fischer R. A. Defective Metal-Organic Frameworks. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1704501 10.1002/adma.201704501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunck D. N.; Dichtel W. R. Bulk Synthesis of Exfoliated Two-Dimensional Polymers Using Hydrazone-Linked Covalent Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135 (40), 14952–14955. 10.1021/ja408243n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Henke S.; Paulus M.; Welle A.; Fan Z.; Rodewald K.; Rieger B.; Fischer R. A. Defect Creation in Surface-Mounted Metal–Organic Framework Thin Films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12 (2), 2655–2661. 10.1021/acsami.9b18672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atzori C.; Shearer G. C.; Maschio L.; Civalleri B.; Bonino F.; Lamberti C.; Svelle S.; Lillerud K. P.; Bordiga S. Effect of Benzoic Acid as a Modulator in the Structure of UiO-66: An Experimental and Computational Study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121 (17), 9312–9324. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b00483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjiivanov K. I.; Panayotov D. A.; Mihaylov M. Y.; Ivanova E. Z.; Chakarova K. K.; Andonova S. M.; Drenchev N. L. Power of Infrared and Raman Spectroscopies to Characterize Metal-Organic Frameworks and Investigate Their Interaction with Guest Molecules. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121 (3), 1286–1424. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lässig D.; Lincke J.; Krautscheid H. Highly Functionalised 3,4,5-Trisubstituted 1,2,4-Triazoles for Future Use as Ligands in Coordination Polymers. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51 (4), 653–656. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.11.098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vasylevs’kyy S. I.; Senchyk G. A.; Lysenko A. B.; Rusanov E. B.; Chernega A. N.; Jezierska J.; Krautscheid H.; Domasevitch K. V.; Ozarowski A. 1,2,4-Triazolyl-Carboxylate-Based MOFs Incorporating Triangular Cu(II)-Hydroxo Clusters: Topological Metamorphosis and Magnetism. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53 (7), 3642–3654. 10.1021/ic403148f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysenko A. B.; Senchyk G. A.; Domasevitch K. V.; Kobalz M.; Krautscheid H.; Cichos J.; Karbowiak M.; Neves P.; Valente A. A.; Gonçalves I. S. Triazolyl, Imidazolyl, and Carboxylic Acid Moieties in the Design of Molybdenum Trioxide Hybrids: Photophysical and Catalytic Behavior. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56 (8), 4380–4394. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b02986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erhart O.; Georgiev P. A.; Krautscheid H. Desolvation Process in the Flexible Metal–Organic Framework [Cu(Me-4py-Trz-Ia)], Adsorption of Dihydrogen and Related Structure Responses. CrystEngComm 2019, 21 (43), 6523–6535. 10.1039/C9CE00992B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lässig D.; Lincke J.; Moellmer J.; Reichenbach C.; Moeller A.; Gläser R.; Kalies G.; Cychosz K. A.; Thommes M.; Staudt R.; Krautscheid H. A Microporous Copper Metal-Organic Framework with High H2 and CO2 Adsorption Capacity at Ambient Pressure. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50 (44), 10344–10348. 10.1002/anie.201102329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobalz M.; Lincke J.; Kobalz K.; Erhart O.; Bergmann J.; Lässig D.; Lange M.; Möllmer J.; Gläser R.; Staudt R.; Krautscheid H. Paddle Wheel Based Triazolyl Isophthalate MOFs: Impact of Linker Modification on Crystal Structure and Gas Sorption Properties. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55 (6), 3030–3039. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b02921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preißler-Kurzhöfer H.; Kolesnikov A.; Lange M.; Möllmer J.; Erhart O.; Kobalz M.; Hwang S.; Chmelik C.; Krautscheid H.; Gläser R. Hydrocarbon Sorption in Flexible MOFs—Part II: Understanding Adsorption Kinetics. Nanomaterials 2023, 13 (3), 601. 10.3390/nano13030601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preißler-Kurzhöfer H.; Lange M.; Kolesnikov A.; Möllmer J.; Erhart O.; Kobalz M.; Krautscheid H.; Gläser R. Hydrocarbon Sorption in Flexible MOFs—Part I: Thermodynamic Analysis with the Dubinin-Based Universal Adsorption Theory (D-UAT). Nanomaterials 2022, 12 (14), 2415. 10.3390/nano12142415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kultaeva A.; Biktagirov T.; Bergmann J.; Hensel L.; Krautscheid H.; Pöppl A. A Combined Continuous Wave Electron Paramagnetic Resonance and DFT Calculations of Copper-Doped 3∞ [Cd0.98Cu0.02(Prz-Trz-Ia)] Metal-Organic Framework. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 31030–31038. 10.1039/C7CP06420A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kultaeva A.; Biktagirov T.; Neugebauer P.; Bamberger H.; Bergmann J.; Van Slageren J.; Krautscheid H.; Pöppl A. Multifrequency EPR, SQUID, and DFT Study of Cupric Ions and Their Magnetic Coupling in the Metal–Organic Framework Compound ∞3[Cu(prz–trz–ia)]. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119 (33), 19171–19179. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b08327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El Mkami H.; Mohideen M. I. H.; Pal C.; McKinlay A.; Scheimann O.; Morris R. E. EPR and Magnetic Studies of a Novel Copper Metal Organic Framework (STAM-I). Chem. Phys. Lett. 2012, 544, 17–21. 10.1016/j.cplett.2012.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Šimenas M.; Matsuda R.; Kitagawa S.; Poppl A.; Banys J. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Study of Guest Molecule-Influenced Magnetism in Kagome Metal-Organic Framework. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120 (48), 27462–27467. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b09853. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Šimenas M.; Kobalz M.; Mendt M.; Eckold P.; Krautscheid H.; Banys J.; Pöppl A. Synthesis, Structure, and Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Study of a Mixed Valent Metal - Organic Framework Containing Cu2 Paddle-Wheel Units. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119 (9), 4898–4907. 10.1021/jp512629c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friedländer S.; Šimenas M.; Kobalz M.; Eckold P.; Ovchar O.; Belous A. G.; Banys J.; Krautscheid H.; Pöppl A. Single Crystal Electron Paramagnetic Resonance with Dielectric Resonators of Mononuclear Cu2+ Ions in a Metal-Organic Framework Containing Cu2 Paddle Wheel Units. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119 (33), 19171–19179. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b05019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marx S.; Kleist W.; Baiker A. Synthesis, Structural Properties, and Catalytic Behavior of Cu-BTC and Mixed-Linker Cu-BTC-PyDC in the Oxidation of Benzene Derivatives. J. Catal. 2011, 281 (1), 76–87. 10.1016/j.jcat.2011.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaervik M.; Dietrich P. M.; Thissen A.; Radnik J.; Nefedov A.; Natzeck C.; Wöll C.; Unger W. E. S. Application of Near-Ambient Pressure X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (NAP-XPS) in an in-Situ Analysis of the Stability of the Surface-Supported Metal-Organic Framework HKUST-1 in Water, Methanol and Pyridine Atmospheres. J. Electr. Spectr. Rel. Phen. 2021, 247, 147042 10.1016/j.elspec.2020.147042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Zhang J. Microstrain and Grain-Size Analysis from Diffraction Peak Width and Graphical Derivation of High-Pressure Thermomechanics. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008, 41 (6), 1095–1108. 10.1107/S0021889808031762. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kou Z.; Hashemi A.; Puska M. J.; Krasheninnikov A. V.; Komsa H.-P. Simulating Raman Spectra by Combining First-Principles and Empirical Potential Approaches with Application to Defective MoS2. npj Comput. Mater. 2020, 6, 59. 10.1038/s41524-020-0320-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shlimak I.; Kaveh M. Raman Spectra in Irradiated Graphene: Line Broadening, Effects of Aging and Annealing. Graphene 2020, 9 (2), 106432 10.4236/graphene.2020.92002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile F. S.; Pannico M.; Causà M.; Mensitieri G.; Di Palma G.; Scherillo G.; Musto P. Metal Defects in HKUST-1 MOF Revealed by Vibrational Spectroscopy: A Combined Quantum Mechanical and Experimental Study. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8 (21), 10796–10812. 10.1039/D0TA01760D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nuhnen A.; Janiak C. A Practical Guide to Calculate the Isosteric Heat/Enthalpy of Adsorption: Via Adsorption Isotherms in Metal-Organic Frameworks, MOFs. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 10295–10307. 10.1039/D0DT01784A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharad P. A.; Nikam A. V.; Thomas F.; Gopinath C. S. CuOx-TiO2 Composites: Electronically Integrated Nanocomposites for Solar Hydrogen Generation. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3 (43), 12022–12030. 10.1002/slct.201802047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roy K.; Gopinath C. S. UV Photoelectron Spectroscopy at near Ambient Pressures: Mapping Valence Band Electronic Structure Changes from Cu to CuO. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86 (8), 3683–3687. 10.1021/ac4041026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnanakumar E. S.; Naik J. M.; Manikandan M.; Raja T.; Gopinath C. S. Role of Nanointerfaces in Cu- and Cu + Au-Based near-Ambient-Temperature CO Oxidation Catalysts. ChemCatChem. 2014, 6 (11), 3116–3124. 10.1002/cctc.201402581. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Kirlikovali K. O.; Idrees K. B.; Wasson M. C.; Farha O. K. Porous Materials for Hydrogen Storage. Chem. 2022, 8, 693–716. 10.1016/j.chempr.2022.01.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fairley N.; Fernandez V.; Richard-Plouet M.; Guillot-Deudon C.; Walton J.; Smith E.; Flahaut D.; Greiner M.; Biesinger M.; Tougaard S.; Morgan D.; Baltrusaitis J. Systematic and Collaborative Approach to Problem Solving Using X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2021, 5, 100112 10.1016/j.apsadv.2021.100112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anomalous Paramagnetism of Copper Acetate. Proc. R. Soc. London A Math. Phys. Sci. 1952, 214 ( (1119), ), 451–465. 10.1098/rspa.1952.0181 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll S.; Schweiger A. EasySpin, a Comprehensive Software Package for Spectral Simulation and Analysis in EPR. J. Magn. Reson. 2006, 178 (1), 42–55. 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afshariazar F.; Morsali A.; Sorbara S.; Padial N. M.; Roldan-Molina E.; Oltra J. E.; Colombo V.; Navarro J. A. R. Impact of Pore Size and Defects on the Selective Adsorption of Acetylene in Alkyne-Functionalized Nickel(II)-Pyrazolate-Based MOFs. Chem.—Eur. J. 2021, 27 (46), 11837–11844. 10.1002/chem.202100821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H.; Thibault C. G.; Wang H.; Cychosz K. A.; Thommes M.; Li J. Effect of Temperature on Hydrogen and Carbon Dioxide Adsorption Hysteresis in an Ultramicroporous MOF. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016, 219, 186–189. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2015.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Himsl D.; Wallacher D.; Hartmann M. Improving the Hydrogen-Adsorption Properties of a Hydroxy-Modified MIL-53(Al) Structural Analogue by Lithium Doping. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48 (25), 4639–4642. 10.1002/anie.200806203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B.; Zhao X.; Putkham A.; Hong K.; Lobkovsky E. B.; Hurtado E. J.; Fletcher A. J.; Thomas K. M. Surface Interactions and Quantum Kinetic Molecular Sieving for H2 and D2 Adsorption on a Mixed Metal–Organic Framework Material. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130 (20), 6411–6423. 10.1021/ja710144k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.; Samsonenko D. G.; Yoon M.; Yoon J. W.; Hwang Y. K.; Chang J.-S.; Kim K. Temperature-Triggered Gate Opening for Gas Adsorption in Microporous Manganese Formate. Chem. Commun. 2008, 39, 4697. 10.1039/b811087e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H.; Kalidindi S. B.; Um Y.; Bureekaew S.; Schmid R.; Fischer R. A.; Hirscher M. A Cryogenically Flexible Covalent Organic Framework for Efficient Hydrogen Isotope Separation by Quantum Sieving. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52 (50), 13219–13222. 10.1002/anie.201307443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.