Abstract

Background

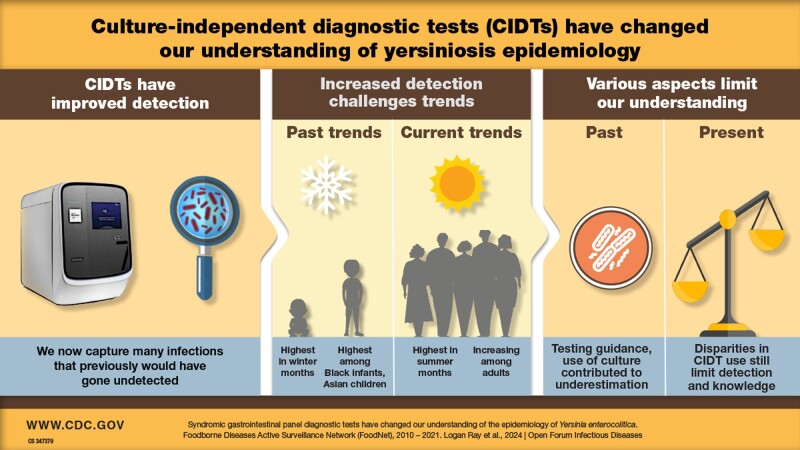

In the US, yersinosis was understood to predominantly occur in winter and among Black or African American infants and Asian children. Increased use of culture-independent diagnostic tests (CIDTs) has led to marked increases in yersinosis diagnoses.

Methods

We describe differences in the epidemiology of yersiniosis diagnosed by CIDT versus culture in 10 US sites, and identify determinants of health associated with diagnostic method.

Results

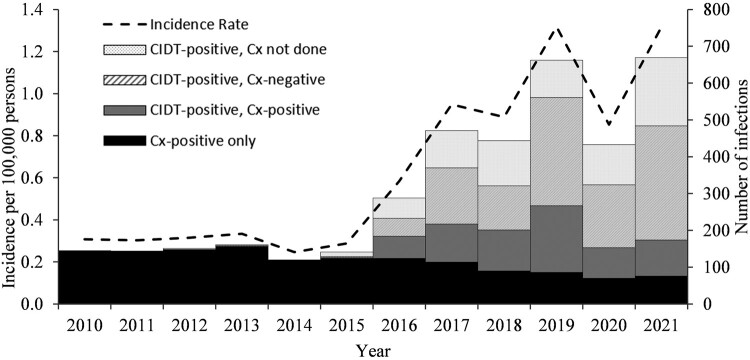

Annual reported incidence increased from 0.3/100 000 in 2010 to 1.3/100 000 in 2021, particularly among adults ≥18 years, regardless of race and ethnicity, and during summer months. The proportion of CIDT-diagnosed infections increased from 3% in 2012 to 89% in 2021. An ill person’s demographic characteristics and location of residence had a significant impact on their odds of being diagnosed by CIDT.

Conclusions

Improved detection due to increased CIDT use has altered our understanding of yersinosis epidemiology, however differential access to CIDTs may still affect our understanding of yersinosis.

Keywords: culture-independent diagnostic tests, Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, FoodNet, syndromic gastrointestinal panel tests, Yersinia enterocolitica

Graphical Abstract

Graphical abstract.

Clinical laboratory adoption of syndromic gastrointestinal panel tests, which are more sensitive than culture methods and simultaneously test for multiple pathogens, resulted in marked increases in detection of Yersinia enterocolitica, especially among groups not previously thought to be of concern.

BACKGROUND

In the United States, it was previously estimated that approximately 117 000 human enteric yersinosis cases caused by Yersinia enterocolitica (henceforth referred to as yersinosis) occur annually [1]. Y enterocolitica is a pharyngeal commensal bacterium in swine, and pork is the most common food associated with yersiniosis [1–3]. Infection in young children and infants typically includes acute febrile diarrhea and may be accompanied by abdominal pain and stool containing leukocytes, blood, and mucus. In older children and adults, right-sided abdominal pain and fever are the predominant symptoms [3]. Outbreaks in the United States have been primarily associated with undercooked pork and contaminated dairy products [4].

Historically, Black or African American infants have had the highest incidence, and many infections were believed to be associated with home preparation of chitterlings [5, 6]. Preparing chitterlings involves cleaning and cooking raw pork intestines, which can be fecally contaminated [5]. Incidence among this group decreased markedly in the 1990s, likely because of increased availability of precleaned product and public health prevention campaigns [7]. In 2007, the population most affected by yersiniosis changed from Black or African American infants to Asian children aged <5 years [8]. Persons aged >5 years have historically had the lowest incidence [7, 8].

Detecting Y enterocolitica using culture-based (Cx) methods is difficult even when selective agents are used, and unsuccessful culture attempts contribute to underestimation of disease burden [9, 10]. For every culture-positive Y enterocolitica infection, an estimated 123 illnesses remain undetected, and only 24% of reflex cultures for Y enterocolitica in FoodNet sites yielded an isolate in 2021 [1, 11]. Yersinia's lack of distinctive colony morphology and slow growth rate results in overgrowth by other fecal microflora and hampers isolate recovery [3, 12]. Reductions in the capacity of clinical laboratories to detect Yersinia and inaccuracies in the databases used for isolate speciation further limit our ability to accurately estimate incidence using Cx methods [13].

Culture-independent diagnostic tests (CIDTs), which include nucleic acid amplification tests and antigen-based tests, are generally more sensitive and provide results faster than Cx tests [14–16]. Syndromic gastrointestinal panel tests are nucleic acid amplification assays that simultaneously test a single specimen for multiple bacterial, viral, and parasitic targets [17]. Since 2013, when the first panel test with a Y enterocolitica target became commercially available, use by clinical laboratories has continuously increased globally [10, 16, 18, 19].

Yersiniosis is not a nationally notifiable infection in the United States, but data on laboratory-diagnosed infections are collected by the Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet). In 2016, FoodNet first reported large increases in the number of yersiniosis infections, the majority of which were detected using CIDT [20]. This increase parallels CIDT-driven increases in yersiniosis incidence in the United Kingdom, Australia, and elsewhere [21, 22]. Our objectives were to characterize the impact of CIDT adoption on yersiniosis incidence in the FoodNet catchment population, describe how the use of Cx tests has affected our understanding of yersiniosis epidemiology in the United States, and how increasing CIDT usage has and may continue to alter this understanding.

METHODS

FoodNet is a collaboration among the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 10 state health departments, the US Department of Agriculture's Food Safety and Inspection Service, and the Food and Drug Administration. FoodNet personnel conduct active, population-based surveillance for laboratory-diagnosed Y enterocolitica infections in 10 sites representing 15% of the US population. Sites include the states of Connecticut, Georgia, Maryland, Minnesota, New Mexico, Oregon, Tennessee, and selected counties in California, Colorado, and New York. In addition to laboratory data, sites collect demographic and clinical information from case interview. FoodNet began collecting data on CIDT-detected infections in 2012. Symptom information on fever were available for cases in 2010 through 2021, and on diarrhea and bloody diarrhea for cases in 2011 through 2021. Case data were geocoded and linked to census tract and county-level socioeconomic and demographic data.

A yersiniosis infection was defined as a Cx-positive result if the pathogen was identified using a Cx-based method as Y enterocolitica. Cx-positive detections without an identified species were also considered Y enterocolitica infections. Infections detected by CIDT were defined as CIDT-positive, regardless of reflex culture results. The term syndromic panel (ie, CIDT) is used for Food and Drug Administration–approved polymerase chain reaction–based panels with >5 targets designed to diagnose enteric infections. We defined infants as persons aged <1 year old and adults as persons aged ≥18 years old. We calculated incidence rates (IRs), incidence rate ratios (IRRs), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and P values using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), and determined statistical significance (P < .5) using the 2-tailed Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test. A supplementary analysis was conducted to compare incidence within strata for each period considered (Supplementary Table 1).

Counterfactual Analyses

Counterfactual random forest (CFRF) analysis was used to identify disparities in the use of Cx and CIDT for Y enterocolitica detection. Specifically, CFRF was used to identify associations between individual and community-level (census tract or county) social determinants of health (SDOH) and the use of CIDT versus Cx (reference-level) for detection. CFRF produces odds ratios for individual variables while adjusting for all other variables in the model [23–29]. All CFRF analyses were conducted in R version 4.04.

SDOH data were obtained from publicly available clearinghouses such as Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, County Health Rankings, CDC Wonder, and US Department of Agriculture Food Environmental Atlas [24, 30, 31]. The original set of SDOH linked with the surveillance data (henceforth termed the “feature set”) was reduced to remove factors with unrealistic values, and with insufficient temporal or spatial resolution (eg, only available at the state level). SDOH data were transformed and cleaned and patterns of missingness for each factor were assessed. Conceptually similar or redundant factors were also identified. Factors were selected to ensure that metrics representing community demographics, food environment, health care environment, and socioeconomic characteristics were present in the reduced feature set. Missing data were singly imputed for each factor using the impute.rfsrc function from the randomForestSRC package with 1000 trees and 5 iterations. Following imputation, the feature set was further reduced to minimize conceptual redundancy. When 2 or more factors were conceptually similar, the factor with greater temporal and spatial resolution and the least missingness in the unimputed dataset was preferentially retained. When choosing between conceptually similar or correlated factors, the interpretability and utility of each factor for informing public health policy were also considered. A final round of feature reduction was implemented to identify highly correlated factors. If the correlation coefficient between 2 factors was >0.60, then the factor that was more strongly correlated with all other factors in the feature set was dropped; correlations between all numeric SDOH in feature set were visualized [32]. Boxplots were also used to inform which correlated or conceptually redundant factor was retained. The final feature set considered here included the following community-level SDOH: Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) variables representing socioeconomic status, minority status and language (MSL), and housing type and transport (CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index [2010, 2014, 2016, 2018] Database US. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/data_documentation_download.html); preventable hospital stay rate (PHR; University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps 2023. www.countyhealthrankings.org); a medically underserved area (Social Determinants of Health Database. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://www.ahrq.gov/sdoh/data-analytics/sdoh-data.html); urbanicity (NCHS Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties, National Center for Healthcare Statistics, MD. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/urban_rural.html); influenza vaccination rate (University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps 2023. www.countyhealthrankings.org); and the percentage of Medicare enrollees with diabetes receiving a hemoglobin A1c test (University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps 2023. www.countyhealthrankings.org) (see Table 3 for definitions). Five individual-level factors (age, ethnicity, race, sex, and state of residence) were also included in the CFRF analyses, as were 6 features representing timing severity of illness. One person with missing sex data was dropped from the CFRF analysis. “Data Not Reported” was added as an explicit category for the 3 symptom variables, race, and ethnicity because of missing data. We could not include persons that identified as Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (NHOPI) as a separate race category due to the small number of persons who identified as NHOPI (N = 9). Instead, we included persons identifying as NHOPI with persons who identified as a race not otherwise listed; this allowed us to retain these records in the dataset.

Table 3.

Continuousa Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) Associated With Yersinia enterocolitica Infection Detection by CIDT as Opposed to Culture-based Methods According to Counterfactual Random Forest Analysis—Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 2010–2021

| Characteristic | Decile Bounds | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | OR | (95% CI) b | |

| Percent of Medicare enrollees with diabetes receiving an HbA1c testc | 48.3 | 82.8 | Ref | – |

| 82.8 | 84.3 | 1.02 | (.77-1.35) | |

| 84.3 | 85.3 | 1.15 | (.87-1.51) | |

| 85.3 | 85.8 | 1.47 | (1.10-1.97)b | |

| 85.8 | 86.4 | 0.93 | (.70-1.25) | |

| 86.4 | 86.8 | 1.57 | (1.18-2.10)b | |

| 86.8 | 87.9 | 1.28 | (.96-1.71) | |

| 87.9 | 88.6 | 1.09 | (.83-1.45) | |

| 88.6 | 89.5 | 1.40 | (1.04-1.88)b | |

| 89.5 | 97.0 | 1.11 | (.84-1.48) | |

| Influenza vaccination rated | 0.17 | 0.42 | Ref | – |

| 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.98 | (.74-1.29) | |

| 0.46 | 0.48 | 1.25 | (.96-1.62) | |

| 0.48 | 0.48 | 1.37 | (.97-1.93) | |

| 0.48 | 0.51 | 1.09 | (.84-1.41) | |

| 0.51 | 0.53 | 1.63 | (1.26-2.11)b | |

| 0.53 | 0.53 | 1.91 | (1.32-2.77)b | |

| 0.54 | 0.56 | 1.49 | (1.16-1.93)b | |

| 0.56 | 0.61 | 2.18 | (1.46-3.27)b | |

| Preventable hospital stay rate (PHR)e | 30.20 | 58.88 | Ref | – |

| 58.88 | 85.11 | 0.29 | (.16-0.54)b | |

| 85.11 | 2754.23 | 11.39 | (7.95-16.32)b | |

| 2754.23 | 3019.95 | 19.46 | (13.00-29.13)b | |

| 3019.95 | 3801.89 | 18.84 | (12.86-27.59)b | |

| 3801.89 | 3981.07 | 22.92 | (15.65-33.58)b | |

| 3981.07 | 4365.16 | 18.27 | (12.43-26.84)b | |

| 4365.16 | 5011.87 | 14.18 | (9.75-20.62)b | |

| 5011.87 | 5623.41 | 20.83 | (14.19-30.58)b | |

| 5623.41 | 12 022.64 | 20.93 | (14.21-30.82)b | |

| Socioeconomic status (SES)f | 0.00 | 0.06 | Ref | – |

| 0.06 | 0.14 | 1.17 | (.87-1.56) | |

| 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.97 | (.73-1.30) | |

| 0.23 | 0.29 | 1.28 | (.95-1.71) | |

| 0.29 | 0.36 | 1.00 | (.75-1.34) | |

| 0.36 | 0.43 | 1.02 | (.77-1.37) | |

| 0.43 | 0.52 | 1.15 | (.86-1.54) | |

| 0.52 | 0.63 | 1.00 | (.75-1.34) | |

| 0.63 | 0.78 | 1.13 | (.84-1.51) | |

| 0.78 | 1.00 | 0.97 | (.73-1.30)b | |

| Minority status and language (MSL)f | 0.00 | 0.12 | Ref | – |

| 0.12 | 0.22 | 1.22 | (.92-1.63) | |

| 0.22 | 0.30 | 1.10 | (.82-1.46) | |

| 0.30 | 0.37 | 1.35 | (1.01-1.80)b | |

| 0.37 | 0.45 | 1.21 | (.91-1.62) | |

| 0.45 | 0.52 | 1.62 | (1.21-2.17)b | |

| 0.52 | 0.61 | 1.32 | (.99-1.77) | |

| 0.61 | 0.70 | 1.23 | (.92-1.65) | |

| 0.70 | 0.82 | 1.41 | (1.06-1.89)b | |

| 0.82 | 1.00 | 1.44 | (1.07-1.93)b | |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CIDT, culture-independent diagnostic test; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; OR, odds ratio.

aConterfactual random forest cannot handle continuous variables so continuous features were dichotomized into quintiles. If possible, deciles were created. If deciles could not be created a 9-level factor was generated. For all SDOH, quintile 1 was the reference group. SDOH variables with no evidence of a significant association were not shown; Social Vulnerability Index subindices (SES, housing type, and transport).

bStatistically significant comparisons where P ≤ .05.

cPercent of Medicare enrollees with diabetes who received an HbA1c test. Indicates quality of clinical care available to county residents (higher value = better quality care). Obtained from County Health Rankings (https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/).

dPercent of fee-for-service Medicare enrollees who had an annual flu vaccination. Indicates quality of clinical care available to county residents (higher value = better quality care). Obtained from County Health Rankings (https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/).

ePreventable hospital stay rate for ambulatory care sensitive conditions usually treatable in outpatient settings per 10 000 Medicare enrollees. Higher values indicate that quality outpatient care is not generally available. As such, it is indicative of both health care quality and access. Obtained from County Health Rankings (https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/).

fThe Social Vulnerability Index was developed to identify communities that are most likely to be differentially affected by, and need additional support before, during or after, hazardous events. In addition to an overall index, subindices are available for several themes including SES, MSL, and housing type and transport. Higher rankings indicate communities at greater risk of negative health outcomes. These data were downloaded from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/). When individual SDOHs were included in the model (instead of the SVI indices), there were strong associations with both the individual SES and MSL SDOH (see Supplementary Table 2).

A sensitivity analysis was performed using the following metrics in place of the SVI variables: (1) the percentage of the population that identified as a historically underrepresented minority (University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps 2023. www.countyhealthrankings.org); (2) population that spoke English less than well (University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps 2023. www.countyhealthrankings.org); (3) population < 18 years of age (University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps 2023. www.countyhealthrankings.org); (4) population >64 years of age (University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps 2023. www.countyhealthrankings.org); (5) college graduation rate (Social Determinants of Health Database. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://www.ahrq.gov/sdoh/data-analytics/sdoh-data.html); (6) food insecurity rate (Food Environment Atlas. Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://data.nal.usda.gov/dataset/food-environment-atlas. Accessed February 2023); (7) per capita income (CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index [2010, 2014, 2016, 2018] Database US. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/data_documentation_download.html); and (8) unemployment rate (CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index [2010, 2014, 2016, 2018] Database US. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/data_documentation_download.html). A separate sensitivity analysis was conducted excluding records that were geocoded to county but not census tract (780 of 3049 records); by including county-level corollaries for census tract-level SDOH during imputation we were able to impute missing census tract-level SDOH data.

CFRF analysis identified factors associated with the odds of yersinosis diagnosis using Cx (reference-level) versus CIDT. The CFRF analyses were implemented as previously described [29]. Continuous features were categorized into quantiles, with the first quantile being the reference group because CFRF cannot handle continuous variables. Except for influenza vaccination rate, all continuous factors were discretized into deciles. Influenza vaccination rate was discretized into a 9-level factor. For nontemporal categorical features, the group reporting the lowest proportion of CIDTs was used as the reference.

RESULTS

During 2010 through 2021, a total of 3829 yersinosis infections were reported in FoodNet sites (Figure 1). Eight cases (0.2%) were associated with outbreaks. The reported incidence (per 100 000 persons; IR) was significantly higher in 2016 through 2021 (IR = 1.0) compared with 2010 through 2015 (IR = 0.3; Table 1). From the earlier to later period, reported incidence decreased significantly among Black or African American infants (IRR, 0.4 [95% CI, 0.2-0.6]), but did not change among Asian infants (IRR, 0.7 [95% CI, 0.3-1.4]) or White infants (IRR, 1.4 [95% CI, .9-2.2]). Reported incidence increased among White children aged 1 through 4 years (IRR, 2.4 [95% CI, 1.7-3.5]) and all adults regardless of race and ethnicity (Table 1). During 2016 through 2021, 49% of annual yersinosis infections were detected between May and September compared with 37% in these months during 2010 through 2015. Between May and September, 75% of ill persons during 2016 through 2021 and 68% during 2010 through 2015 identified as White.

Figure 1.

Number of infections and incidence rate of Yersinia enterocolitica* infections diagnosed by culture-based method (Cx) or culture-independent diagnostic tests (CIDT), by year-Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 2010-2021. *There were 253 Cx detected infections reported from species other than Y. enterocolitica that were excluded from analyses: 94 frederiksenii, 67 intermedia, 33 pseudotuberculosis, 28 kristensenii, 17 ruckeri, 5 aldovae, 4 massiliensis, 1 aleksiciae, 1 rohdei.

Table 1.

Number of Yersinia enterocolitica Infections, Incidence Rate, and Incidence Rate Ratio of Infections Comparing 2016–2021 to 2010–2015—Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network

| Characteristic | 2010-2015 | 2016-2021 | 2016-2021 Versus 2010-2015 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | (%)a | IR | No. | (%)a | IR | IRR | (95% CI) b | |

| Age group (y) | ||||||||

| <1 | 128 | (15) | 3.6 | 86 | (3) | 2.6 | 0.7 | (.5-.9) |

| 1-4 | 100 | (12) | 0.7 | 159 | (5) | 1.1 | 1.6 | (1.3-2.1) |

| 5-17 | 125 | (15) | 0.3 | 166 | (6) | 0.3 | 1.3 | (1.1-1.7) |

| 18-59 | 285 | (33) | 0.2 | 1311 | (44) | 0.8 | 4.5 | (4.0-5.2) |

| ≥60 | 224 | (26) | 0.4 | 1245 | (42) | 1.9 | 4.7 | (4.1-5.4) |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 444 | (52) | 0.3 | 1720 | (58) | 1.1 | 3.7 | (3.4-4.1) |

| Male | 418 | (48) | 0.3 | 1246 | (42) | 0.8 | 2.8 | (2.6-3.2) |

| Race | ||||||||

| Asian | 62 | (7) | 0.4 | 118 | (4) | 0.6 | 1.6 | (1.2-2.2) |

| Black or African American | 132 | (15) | 0.3 | 221 | (7) | 0.4 | 1.5 | (1.2-1.9) |

| Identified as >1 race | 7 | (1) | 0.1 | 25 | (1) | 0.3 | 3.0 | (1.3-6.9) |

| Identified as a race not otherwise specified | 26 | (3) | – | 66 | (2) | – | – | – |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 4 | (0) | 0.1 | 17 | (1) | 0.4 | 3.9 | (1.3-11.5) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 2 | (0) | 0.4 | 7 | (0) | 1.2 | 3.0 | (1.3-6.9) |

| Not reported | 93 | (11) | – | 345 | (12) | … | – | – |

| White | 536 | (62) | 0.2 | 2168 | (73) | 1.0 | 4.0 | (3.6-4.4) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 71 | (8) | 0.2 | 205 | (7) | 0.5 | 2.5 | (2.0-3.4) |

| Non-Hispanic | 664 | (77) | 0.3 | 2318 | (78) | 0.9 | 3.4 | (3.1-3.7) |

| Not reported | 127 | (15) | – | 444 | (15) | – | – | – |

| State | ||||||||

| Californiac | 63 | (7) | 0.3 | 109 | (4) | 0.5 | 1.6 | (1.2-2.2) |

| Coloradoc | 50 | (6) | 0.3 | 294 | (10) | 1.5 | 5.4 | (4.0-7.3) |

| Connecticut | 71 | (8) | 0.3 | 399 | (13) | 1.9 | 5.6 | (4.4-7.3) |

| Georgia | 193 | (22) | 0.3 | 421 | (14) | 0.7 | 2.1 | (1.7-2.4) |

| Maryland | 71 | (8) | 0.2 | 396 | (13) | 1.1 | 5.4 | (4.2-7.0) |

| Minnesota | 111 | (13) | 0.3 | 600 | (20) | 1.8 | 5.2 | (4.2-6.4) |

| New Mexico | 9 | (1) | 0.1 | 39 | (1) | 0.3 | 4.3 | (2.1-8.9) |

| New Yorkc | 92 | (11) | 0.4 | 208 | (7) | 0.8 | 2.3 | (1.8-2.9) |

| Oregon | 110 | (13) | 0.5 | 240 | (8) | 1.0 | 2.0 | (1.6-2.6) |

| Tennessee | 92 | (11) | 0.2 | 261 | (9) | 0.6 | 2.7 | (2.1-3.4) |

| Month of illness | ||||||||

| January | 89 | (10) | 0.2 | 213 | (7) | 0.4 | 2.3 | (1.8-2.9) |

| February | 60 | (7) | 0.1 | 193 | (7) | 0.4 | 3.1 | (2.3-4.1) |

| March | 71 | (8) | 0.1 | 213 | (7) | 0.4 | 2.9 | (2.2-3.8) |

| April | 90 | (10) | 0.2 | 227 | (8) | 0.5 | 2.4 | (1.9-3.1) |

| May | 59 | (7) | 0.1 | 247 | (8) | 0.5 | 4.0 | (3.0-5.3) |

| June | 70 | (8) | 0.1 | 283 | (10) | 0.6 | 3.9 | (3.0-5.0) |

| July | 68 | (8) | 0.1 | 331 | (11) | 0.7 | 4.7 | (3.6-6.1) |

| August | 63 | (7) | 0.1 | 304 | (10) | 0.6 | 4.6 | (3.5-6.1) |

| September | 56 | (6) | 0.1 | 288 | (10) | 0.6 | 4.9 | (3.7-6.6) |

| October | 61 | (7) | 0.1 | 244 | (8) | 0.5 | 3.8 | (2.9-5.1) |

| November | 77 | (9) | 0.2 | 214 | (7) | 0.4 | 2.7 | (2.1-3.5) |

| December | 98 | (11) | 0.2 | 210 | (7) | 0.4 | 2.1 | (1.6-2.6) |

| Total | 862 | (100) | 0.3 | 2967 | (100) | 3.3 | … | (3.1-3.6) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IR, incidence rate per 100 000 persons; IRR, unadjusted incidence rate ratio; –, not applicable.

aPercentage for total in each category were calculated using total number of cases (862 for 2010-2015, 2967 for 2016-2021).

bAll comparisons were statistically significant where P ≤ .01 except for age group 5-17 (P = .02), and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander Race (P = .15).

cSelect counties in California, Colorado, and New York.

Most infections during the study period (2433, 64%) were detected by a CIDT, and CIDT-based detection increased throughout the study period (3% in 2012, 57% in 2016, 89% in 2021). Most CIDT-positive infections were detected by commercially available syndromic panel tests (2372, 97%), including the BioFire FilmArray Gastrointestinal Panel (1909, 78%), the Luminex VERIGENE Enteric Pathogens Test (356, 16%), and the BD Max Extended Enteric Bacterial Panel (51, 2%). Among CIDT-positive infections, reflex culture was attempted for 1742 (72%) of infections and yielded an isolate for 640 (37%) specimens.

The probability of a yersinosis infection being detected by CIDT compared with Cx increased from 1% in 2010 through 2013 to 87% in 2020 through 2021 (odds ratio [OR], 126.9; 95% CI, 79.9-201.6). After controlling for all other variables, patient demographics and symptoms were also significantly associated with detection method. The probability of CIDT-based detection increased with age, and odds of CIDT (vs Cx) detection were 1.45 times greater for White than Asian persons (95% CI, 1.07-1.97; Table 2). Those with fever had a lower odds of CIDT-based detection than those without fever (OR,0.79; 95% CI, .68-.91). Those with unknown symptom data for diarrhea and bloody diarrhea had a significantly higher likelihood of CIDT (vs Cx) detection despite there being no significant difference in the likelihood of CIDT (vs Cx-based) detection for those reporting versus not reporting symptoms.

Table 2.

Categorical Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) Associated With Yersinia enterocolitica Infection Detection by CIDT as Opposed to Culture-based Tests According to Counterfactual Random Forest Analysis—Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 2010-2021

| Characteristica | OR | (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Bloody diarrheab | ||

| No | Ref | – |

| Yes | 1.02 | (.88-1.18) |

| Not reported | 1.25 | (1.02-1.54)c |

| Diarrheab | ||

| No | Ref | – |

| Yes | 0.91 | (.72-1.14) |

| Not reported | 1.84 | (1.50-1.26)c |

| Feverc | ||

| No | Ref | – |

| Yes | 0.79 | (.68-0.91)c |

| Not reported | 0.80 | (.67-0.95)c |

| State of residence | ||

| California | 2.25 | (1.55-3.27)c |

| Colorado | 3.66 | (2.67-5.01)c |

| Connecticut | 2.39 | (1.80-3.18)c |

| Georgia | 2.76 | (2.11-3.63)c |

| Maryland | 2.92 | (2.19-3.89)c |

| Minnesota | 3.73 | (2.85-4.88)c |

| New Mexico | 1.91 | (1.03-3.52)c |

| New York | 1.10 | (.80-1.51) |

| Oregon | Ref | – |

| Tennessee | 2.36 | (1.75-3.20)c |

| Age group | ||

| <1 y | Ref | – |

| 1-5 y | 1.62 | (1.12-2.34)c |

| 5-18 y | 1.53 | (1.07-2.20)c |

| 18-60 y | 2.32 | (1.72-3.13)c |

| ≥60 y | 2.29 | (1.69-3.08)c |

| Raced | ||

| Asian | Ref | – |

| Black or African American | 1.08 | (.75-1.55) |

| Native American or Alaskan Native | 1.51 | (.59-3.9) |

| Identified as > 1 race | 1.67 | (.75-3.7) |

| Identified as a race not otherwise specified | 1.34 | (.81-2.2) |

| Not reported | 1.14 | (.80-1.61) |

| White | 1.45 | (1.07-1.97)c |

| Month of Illness | ||

| January | Ref | – |

| February | 1.41 | (1.02-1.96)c |

| March | 1.32 | (.95-1.84) |

| April | 1.43 | (1.03-1.99)c |

| May | 0.99 | (.70-1.38) |

| June | 1.04 | (.75-1.45) |

| July | 1.12 | (.81-1.54) |

| August | 1.24 | (.89-1.71) |

| September | 1.45 | (1.06-2.00)c |

| October | 1.55 | (1.13-2.11)c |

| November | 1.46 | (1.06-2.00)c |

| December | 1.51 | (1.09-2.08)c |

| Year of illnesse | ||

| 2010-2013 | Ref | – |

| 2014-2015 | 2.30 | (1.23-4.33)c |

| 2016-2017 | 56.22 | (35.42-89.23)c |

| 2018-2019 | 108.94 | (68.75-172.6)c |

| 2020-2021 | 126.93 | (79.91-201.6)c |

| Census tract urbanicityc,f | ||

| Large Central Metro Area | Ref | – |

| Large Fringe Metro Area (Suburbs) | 1.38 | (1.14-1.66)c |

| Medium Metro Area | 1.2 | (.97-1.49) |

| Small Metro Area | 1.16 | (.87-1.53) |

| Micropolitan | 1.22 | (.96-1.56) |

| Noncore (Rural) | 1.66 | (1.19-2.31)c |

| Medically underserved area (MUA)g | ||

| Not MUA | Ref | – |

| MUA | 0.66 | (.49–0.89)c |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CIDT, culture-independent diagnostic test; OR, odds ratio.

aSDOH variables with no evidence of a significant association are not shown: ethnicity, hospitalization status, and sex.

bData for illness symptoms were available for 2011-2021. A sensitivity analysis was conducted using data (1) from all years and (2) using data from 2011 to 2021. Model results and interpretation were robust to the inclusion/exclusion of all or part of the data. The results for the model built using all years of data (2010-2021) are reported in the main text, whereas results from analyses using a subset of years are reported in the Supplementary supplemental materials.

cStatistically significant comparisons where P ≤ .05.

dBecause of small numbers of incident cases (N = 9), individuals identifying as Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander were included with individuals who identified as a race not otherwise listed.

eGeo-referenced census tract data during 2021 were only available for Georgia at the time of publication. A sensitivity analysis was conducted using data (1) from all states in all years, (2) using data from all states for 2010 through 2020, but for Georgia only for 2021, and (3) excluding all 2021 data. Model results and interpretation were robust to the inclusion/exclusion of all or part of the 2021 data.

fCensus tract urbanicity (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/urban_rural.htm).

gA medically underserved tract is defined as a tract with a lack of access to primary care services. These data were downloaded from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (https://www.ahrq.gov/sdoh/data-analytics/sdoh-data.html).

Location of residence was strongly associated with method of detection. Odds of CIDT-based detection were 3.7 times higher for persons in Colorado (95% CI, 2.7-5.0) and Minnesota (95% CI, 2.9–4.9) compared with Oregon (Table 2). Persons living in suburban (OR,= 1.4; 95% CI, 1.1-1.7) and rural (OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.2-2.3) counties were more likely to be diagnosed using CIDT than persons in large metropolitan counties (Table 3). Persons living in census tracts with a higher SVI MSL ranking and higher college graduation and influenza vaccination rates were more likely to be diagnosed by CIDT than those living in tracts with a lower ranking and lower graduation and vaccination rates (Tables 3, Supplementary Table 2). (A higher MSL ranking corresponds to counties where more of the population identify as a historically underrepresented minority or speak English less than well [33]). Odds of CIDT-based detection for persons living in tracts with the highest MSL rankings was 1.4 (95% CI, 1.1-1.9) times greater than those from counties with the lowest rankings (Table 3). Persons living in medically underserved tracts and tracts with a higher PHR were less likely to be diagnosed by CIDT compared with Cx-based test, as were persons in counties where a higher proportion of the population were food insecure or unemployed (Tables 3, Supplementary Table 2). (Higher PHR values indicate that quality outpatient care is less available.) Odds of CIDT-based detection were 1.4 and 1.7 times lower for persons living in counties with the highest (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, .4-.7) and second highest (OR, 0.44; 95% CI, .3-.6) food insecurity rates compared with persons in counties with the lowest rate (Supplementary Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Our analysis reveals that the historic understanding of the epidemiology of yersiniosis likely missed key populations. The rapid adoption of syndromic gastrointestinal panel tests resulted in marked increases in detections, especially among groups that were not previously thought to be of concern. Reported incidence increased among adults regardless of race and ethnicity. Access to medical care, including testing and test type, continues to affect likelihood of detection.

Before the adoption of syndromic panel tests, most clinical laboratories in the United States did not routinely test for Yersinia [18, 22, 34]. To reduce costs, US clinical laboratories may have adopted selective testing recommendations to only perform Cx detection for infections occurring “in fall or winter, for certain at-risk populations” [35]. Similarly, UK laboratories only performed Cx-based tests if there was a clinical suspicion of yersinosis [22]. Although these recommendations were developed to preserve public health resources and were based on known epidemiology at the time, restricting testing to specific populations and seasons appears to have created an incomplete epidemiologic picture and amplified underdiagnosis. Indeed, yersinosis incidence has not increased as sharply, compared to the United States and United Kingdom, in New Zealand, where all diagnostic fecal samples were historically tested for Yersinia. Moreover, in New Zealand, rates increased significantly from 2010 to 2019, but CIDTs were not widely available until 2017 [36]. In the United States, CIDT is likely providing a more complete picture of yersiniosis by capturing previously undiagnosed infections and is unlikely to represent a true increase for particular subgroups; this conclusion is consistent with findings from studies conducted in other countries [22, 36]. Our findings highlight biases in historic clinical testing practices, resulting in the underestimation of disease burden for specific populations. Comparisons of persons diagnosed using Cx and CIDT methods in our study also indicate that differential access to CIDTs may continue to affect our understanding of yersinosis epidemiology; this is a conclusion consistent with past studies that examined the impacts of CIDT adoption in Europe [22].

In addition to year, an ill person's location of residence had a substantial and significant impact on the likelihood of being diagnosed by CIDT as opposed to Cx. This is partially attributable to the differential uptake of syndromic panel testing but may also reflect underlying structural inequities in health care access and quality. For instance, living in an area with differential access to resources was associated with a lower likelihood of having a CIDT-detected illness. Persons living in locations classified as medically underserved, with higher rates of unemployment and food insecurity, with a higher MSL ranking, or with lower rates of influenza vaccination and college graduation had a decreased likelihood of having a CIDT-detected illness. In contrast, persons in communities with a higher PHR were more likely to have yersiniosis detected by CIDT. A San Diego, CA, USA, study also reported differences in CIDT adoption for different health care environments; specifically, higher rates of CIDT-based diagnosis were associated with higher hospital-related health care utilization [36, 37]. Overall, our findings suggest that the associations between community environment and CIDT access are complex, and that relying solely on Cx in our historical assessment of disease burden led to an underestimation of burden across communities.

The adoption of CIDTs has not been uniform across laboratories serving communities with varying demographic and SDOH profiles. The likelihood of receiving a CIDT increased substantially with age. Similarly, White persons were significantly more likely to be diagnosed by CIDT compared with Asian persons. This represents a shift from the populations that were historically epidemiologically linked to yersinosis in the United States [7, 8], and mirrors similar shifts associated with increased CIDT use in the United Kingdom and Denmark [22, 38]. Our findings indicate that yersinosis affects persons from all demographic groups, including groups (eg, adults, White persons) not historically linked with an elevated incidence of yersinosis.

Increased use of CIDT and the corresponding increase in reported incidence has also changed our understanding of yersiniosis seasonality. The historic winter association was largely attributed to holiday-associated illnesses among Black or African American infants related to the preparation of chitterlings [8, 39]. The now-greater reported incidence in summer months, particularly among White persons, again indicates the likely historic underdiagnosis of yersiniosis among certain populations. This finding is consistent with studies conducted outside the United States that also noted an increased yersinosis incidence following the advent of CIDTs [22, 38].

Although Cx methods are generally less sensitive than CIDT, culture is used to obtain isolates to determine species, identify outbreaks (by subtyping and finding related strains), and characterize antimicrobial resistance [38]. Most clinical laboratories serving FoodNet sites do not perform reflex culture; many submit stool specimens to public health laboratories where isolate recovery is attempted [18] . Regulations for specimen submission vary by state.

A primary benefit of CIDTs is an increased ability to detect infections; however, it is unclear how many infections represent false positives. Specifically, CIDTs rely on detection of specific DNA sequences for pathogen identification and cannot distinguish between active infectious agents and nonviable bacteria. Asymptomatic shedding, a well-documented phenomenon, can complicate CIDT-based diagnosis [10]. The importance of differentiating asymptomatic and false-positive cases from true symptomatic cases is highlighted by a San Diego, CA, USA, study that investigated the use of CIDTs among patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). This study reported a higher rate of enteric illness detection by CIDTs and determined that this led to misattribution of IBD symptoms to infection, which led to delays in IBD treatment or use of treatments that exacerbated or complicated IBD symptoms. Conversely, an Australian study suggested that low reflex culture rates for Yersinia following CIDT-positive yersinosis diagnosis were attributable to the improved sensitivity of CIDTs compared with Cx not to lower CIDT specificity [21].

In our study, patients reporting fever were more likely to be diagnosed by Cx methods, possibly indicating higher rates of asymptomatic detection or false positives by CIDTs. However, our failure to find evidence of a difference in diagnostic method between those who did and did not report diarrhea or bloody diarrhea contradicts this hypothesis and suggests the diagnosis of symptomatic cases by CIDT. It is noteworthy that patients missing symptom data were more likely to be diagnosed by CIDT, which may reflect differences in data reporting or the quality of care available to yersinosis patients diagnosed by CIDT versus Cx methods. A comparison of several CIDTs and Cx methods found that the CIDTs considered were more sensitive than the Cx methods but did not find evidence of CIDT false positives [40]. This may be attributable to the challenges associated with culture-based Yersinia detection; for instance, direct culturing is usually successful only when a large number Yersinia are present in a sample [37]. Yersinia's slow growth rate means that, even when present and when grown in selective media, Yersinia may not be detected because of the overgrowth of other, faster growing bacterial species [12]. The specificity of CIDT tests and the implication of CIDT specificity for clinical and public health interpretation remains unclear. Consequently, pairing CIDTs with reflex culture, when feasible, has been recommended previously. However, there is a pressing need for additional information on the specificity of CIDTs to aid in interpreting CIDT results in the absence of a positive reflex culture given the difficulties and cost associated with reflex culturing Yersinia.

Although the target for the assay may be Y enterocolitica, there is cross-reactivity with Yersinia kristensenii and Yersinia frederiksenii [41]. CIDT methods are also unable to differentiate the 5 pathogenic Y enterocolitica biotypes (1B, 2, 3, 4, and 5) from biotype 1A, which is generally considered nonpathogenic because of the absence of certain virulence genes. However, Yersinia's pathogenic mechanism is not completely understood, and both biotype 1A and non-enterocolitica and non-pestis Yersinia species have been linked to clinical illnesses [22, 42–47]. Biotype 1A is notifiable in New Zealand and accounts for >20% of New Zealand cases. A UK study that tracked changes in reported yersiniosis incidence from 1975 through 2020 detected Y enterocolitica, Y frederiksenii, Yersinia pseudotuberculosus, and other Yersinia species in 80%, 10%, 7%, and 2% of yersiniosis cases, respectively [36]. Additional studies are needed to better understand the distribution of biotypes detected by CIDTs.

This study has limitations beyond those previously discussed. First, trends in FoodNet may not be representative of the US population. Second, changes in reported incidence and testing practices following the COVID-19 pandemic are not yet fully known. Third, a small number of records were geocoded to county instead of census tract. County-level data were used to impute the missing census tract data for these records. Inclusion of these records did not affect our model results or interpretation based on a sensitivity analysis in which these records were excluded. Last, symptom data for fever, diarrhea, and bloody diarrhea were only available for 2011 through 2021. Identification of a significant difference in diagnostic method for patients reporting yersinosis symptoms versus not would have provided insights into CIDT-based detection of asymptomatic cases or false positives. Our failure to find evidence of such an association limited our ability to hypothesize on this, and was likely, in part, due to missing symptom data (35% for fever, 30% for bloody diarrhea, 24% for diarrhea).

CONCLUSION

The widespread use of syndromic gastrointestinal panel tests for routine stool testing in clinical laboratories has revealed clinical testing practices that prevented a full understanding of the epidemiology of Y enterocolitica infection. The identification of infections by CIDT that previously would have been undiagnosed has resulted in marked increases in yersiniosis diagnoses since 2016, especially among adults, White persons, and during summer. This likely provides a more complete picture of the true burden of disease. However, the adoption of CIDTs has not occurred equally across laboratories serving communities with different demographic and SDOH profiles as suggested by this and previous studies [22]. Without the ability to determine the extent to which differential detection by CIDT versus culture-based tests versus actual epidemiological changes may be influencing our observations, we must exercise caution in overinterpreting the findings of this and similar studies. To disentangle these signals, additional research is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Logan C Ray, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Daniel C Payne, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Joshua Rounds, Minnesota Department of Health, St. Paul, Minnesota, USA.

Rosalie T Trevejo, Oregon Health Authority, Portland, Oregon, USA.

Elisha Wilson, Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, Denver, Colorado, USA.

Kari Burzlaff, New York State Department of Health, Albany, New York, USA.

Katie N Garman, Tennessee Department of Health, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Sarah Lathrop, New Mexico Emerging Infections Program, Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA.

Tamara Rissman, Connecticut Emerging Infections Program, Hartford, Connecticut, USA.

Katie Wymore, California Department of Public Health, Oakland, California, USA.

Sophia Wozny, Maryland Department of Health, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Siri Wilson, Georgia Department of Public Health, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Louise K Francois Watkins, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Beau B Bruce, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Daniel L Weller, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We were grateful for technical assistance from and the subject matter expertise of Hazel Shah, Kennedy Houck, Sonny Hoang, Christine Lee, and Dave Boxrud.

Author Contributions. L. R., D. W., and D. P. conceived of the project ideas, and designed the study. L. R. oversaw data-to-day aspects. L. R., J. R., R. T., E. W., K. B., K. G., S. L., T. R., K. W., and S,W, were the surveillance points of contact. L. R.. and D. W. led data cleaning and analysis efforts with support from B. B. All authors contributed to manuscript development.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Financial support. This work was supported in part by cooperative agreement funding from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Emerging Infections Program, the Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Prevention and Control of Emerging Infectious Diseases Program, and the Association of Public Health Laboratories.

The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

Patient consent. This study does not include factors necessitating patient consent.

References

- 1. Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, et al. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States–major pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis 2011; 17:7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Verhaegen J, Charlier J, Lemmens P, et al. Surveillance of human Yersinia enterocolitica infections in Belgium: 1967–1996. Clin Infect Dis 1998; 27:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schmitz A, Tauxe R. In: Brachman P, Abrutyn E, eds. Bacterial infections of humans. Fourth Edition. 2009:939–957. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gruber JF, Morris S, Warren KA, et al. Yersinia enterocolitica outbreak associated with pasteurized milk. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2021; 18:448–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jones TF, Buckingham SC, Bopp CA, Ribot E, Schaffner W. From pig to pacifier: chitterling-associated yersiniosis outbreak among black infants. Emerg Infect Dis 2003; 9:1007–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee LA, Gerber AR, Lonsway DR, et al. Yersinia enterocolitica O:3 infections in infants and children, associated with the household preparation of chitterlings. N Engl J Med 1990; 322:984–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ray SM, Ahuja SD, Blake PA, et al. Population-based surveillance for Yersinia enterocolitica infections in FoodNet sites, 1996–1999: higher risk of disease in infants and minority populations. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 38(Suppl 3):S181–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ong KL, Gould LH, Chen DL, et al. Changing epidemiology of Yersinia enterocolitica infections: markedly decreased rates in young black children, Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet), 1996–2009. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54:S385–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Savin C, Leclercq A, Carniel E. Evaluation of a single procedure allowing the isolation of enteropathogenic Yersinia along with other bacterial enteropathogens from human stools. PLoS One 2012; 7:e41176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sood N, Carbell G, Greenwald HS, Friedenberg FK. Is the medium still the message? Culture-independent diagnosis of gastrointestinal infections. Dig Dis Sci 2022; 67:16–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Collins JP, Shah HJ, Weller DL, et al. Preliminary incidence and trends of infections caused by pathogens transmitted commonly through food—foodborne diseases active surveillance network, 10 U.S. sites, 2016–2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022; 71:1260–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Korkeala H. Low occurrence of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica in clinical, food, and environmental samples: a methodological problem. Clin Microbiol Rev 2003; 16:220–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tourdjman M, Ibraheem M, Brett M, et al. Misidentification of Yersinia pestis by automated systems, resulting in delayed diagnoses of human plague infections–Oregon and New Mexico, 2010–2011. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:e58–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cronquist AB, Mody RK, Atkinson R, et al. Impacts of culture-independent diagnostic practices on public health surveillance for bacterial enteric pathogens. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54(Suppl 5):S432–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Iwamoto M, Huang JY, Cronquist AB, et al. Bacterial enteric infections detected by culture-independent diagnostic tests–FoodNet, United States, 2012–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015; 64:252–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Murphy CN, Fowler RC, Iwen PC, Fey PD. Evaluation of the BioFire FilmArray(R) GastrointestinalPanel in a Midwestern Academic Hospital. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2017; 36:747–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Clark SD, Sidlak M, Mathers AJ, Poulter M, Platts-Mills JA. Clinical yield of a molecular diagnostic panel for enteric pathogens in adult outpatients with diarrhea and validation of guidelines-based criteria for testing. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019; 6:ofz162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ray LC, Griffin PM, Wymore K, et al. Changing diagnostic testing practices for foodborne pathogens, foodborne diseases active surveillance network, 2012–2019. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022; 9:ofac344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang EW, Bhatti M, Cantu S, Okhuysen PC. Diagnosis of Yersinia enterocolitica infection in cancer patients with diarrhea in the era of molecular diagnostics for gastrointestinal infections. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019; 6:ofz116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marder EP, Cieslak PR, Cronquist AB, et al. Incidence and trends of infections with pathogens transmitted commonly through food and the effect of increasing use of culture-independent diagnostic tests on surveillance—foodborne diseases active surveillance network, 10 U.S. sites, 2013–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017; 66:397–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McLure A, Shadbolt C, Desmarchelier PM, Kirk MD, Glass K. Source attribution of salmonellosis by time and geography in New South Wales, Australia. BMC Infect Dis 2022; 22:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sumilo D, Love NK, Manuel R, et al. Forgotten but not gone: Yersinia infections in England, 1975 to 2020. Euro Surveill 2023; 28:2200516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jackson BR, Gold JAW, Natarajan P, et al. Predictors at admission of mechanical ventilation and death in an observational cohort of adults hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73:e4141–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ishwaran H, Kogalur U. Random survival forests for R. R News 2007; 7:25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ishwaran H, Kogalur U, Blackstone E, Lauer M. Random survival forests. Ann Appl Statist. 2008; 2:841–60. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . Social Determinants of Health Database. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/sdoh/data-analytics/sdoh-data.html. Accessed June 2023.

- 27. Ishwaran H, Kogalur U. Fast Unified Random Forests for Survival, Regression, and Classification (RF-SRC). R package version 3.2.3. 2023. https://cran.r-project.org/package=randomForestSRC. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ishwaran H, Kogalur U. Random survival forests for R. R News. 2007; 7:25–31. https://CRAN.R-project.org/doc/Rnews/. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ishwaran H, Kogalur U, Blackstone E, Lauer M. Random survival forests. Ann Appl Statist 2008; 2:841–60. https://arXiv.org/abs/0811.1645v1. [Google Scholar]

- 30. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index . Available at: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/. Accessed June 2023.

- 31. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC WONDER. . Available at: https://wonder.cdc.gov/. Accessed June 2023.

- 32. Taiyun W, Viliam S. R package “corrplot”: visualization of a correlation matrix (version 0.84). Statistician 2017; 56:e24. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Flanagan BE, Gergory EW, Hallisey EJ, Heitgerd JL, Lewis B. A social vulnerability Index for disaster management. J Homel Secur Emerg Manag 2011; 8:0000102202154773551792. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Voetsch AC, Angulo FJ, Rabatsky-Ehr T, et al. Laboratory practices for stool-specimen culture for bacterial pathogens, including Escherichia coli O157:H7, in the FoodNet sites, 1995–2000. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 38(Suppl 3):S190–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guerrant RL, Van Gilder T, Steiner TS, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of infectious diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 32:331–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rivas L, Strydom H, Paine S, Wang J, Wright J. Yersiniosis in New Zealand. Pathogens 2021; 10:191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ahmad W, Nguyen NH, Boland BS, et al. Comparison of multiplex gastrointestinal pathogen panel and conventional stool testing for evaluation of diarrhea in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Dig Dis Sci 2019; 64:382–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Johansen RL, Schouw CH, Madsen TV, Nielsen XC, Engberg J. Epidemiology of gastrointestinal infections: lessons learned from syndromic testing, Region Zealand, Denmark. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2023; 42:1091–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Yersinia enterocolitica infections during the holidays in black families–Georgia. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1990; 39:819–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Valledor S, Valledor I, Gil-Rodriguez MC, Seral C, Castillo J. Comparison of several real-time PCR kits versus a culture-dependent algorithm to identify enteropathogens in stool samples. Sci Rep 2020; 10:4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. BioFire® Diagnostics . Yersinia enterocolitica detection by the BioFire® FilmArray® gastrointestinal (GI) panel. Salt Lake City, UT.

- 42. Bhagat N, Virdi JS. Distribution of virulence-associated genes in Yersinia enterocolitica biovar 1A correlates with clonal groups and not the source of isolation. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2007; 266:177–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Robins-Browne RM, Tzipori S, Gonis G, Hayes J, Withers M, Prpic JK. The pathogenesis of Yersinia enterocolitica infection in gnotobiotic piglets. J Med Microbiol 1985; 19:297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zheng H, Sun Y, Mao Z, Jiang B. Investigation of virulence genes in clinical isolates of Yersinia enterocolitica. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2008; 53:368–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tuompo R, Hannu T, Huovinen E, Sihvonen L, Siitonen A, Leirisalo-Repo M. Yersinia enterocolitica biotype 1A: a possible new trigger of reactive arthritis. Rheumatol Int 2017; 37:1863–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tennant SM, Grant TH, Robins-Browne RM. Pathogenicity of Yersinia enterocolitica biotype 1A. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2003; 38:127–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hunter E, Greig DR, Schaefer U, et al. Identification and typing of Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis isolated from human clinical specimens in England between 2004 and 2018. J Med Microbiol 2019; 68:538–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.