Abstract

Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV), a natural pathogen of mice, is a member of the genus Cardiovirus in the family Picornaviridae. Structural studies indicate that the cardiovirus pit, a deep depression on the surface of the virion, is involved in receptor attachment; however, this notion has never been systematically tested. Therefore, we used BeAn virus, a less virulent TMEV, to study the effect of site-specific mutation of selected pit amino acids on viral binding as well as other replicative functions of the virus. Four amino acids within the pit, V1091, P1153, A1225 and P3179, were selected for mutagenesis to evaluate their role in receptor attachment. Three amino acid replacements were made at each site, the first a conservative replacement, followed by progressively more radical amino acid changes in order to detect variable effects at each site. A total of seven viable mutant viruses were recovered and characterized for their binding properties to BHK-21 cells, capsid stability at 40°C, viral RNA replication, single- and multistep growth kinetics, and virus translation. Our data implicate three of these residues in TMEV-cell receptor attachment.

Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV), a natural pathogen of mice, is a member of the genus Cardiovirus in the family Picornaviridae, which includes another serogroup, consisting of a number of isolates, including Mengovirus and Encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV). TMEVs can be divided into two groups based on neurovirulence following intracerebral inoculation of mice. Highly virulent strains of TMEV, such as GDVII and FA, cause a rapidly fatal encephalitis, while less virulent strains, such as BeAn and DA, are characterized by at least a 105-fold increase in the mean 50% lethal dose. The less virulent TMEVs cause a persistent infection in the central nervous system of susceptible strains of mice, resulting in immune-mediated demyelination. This animal model has been used as an experimental analogue of multiple sclerosis.

The three-dimensional structures of viruses of all picornavirus genera, except the hepatoviruses, have been solved to an atomic level. TMEVs are not an exception (12, 21, 22). The Theiler's virion is composed of a single-strand, positive-sense RNA molecule, 8.1 kb in size, surrounded by an icosahedral capsid containing 60 copies each of the four capsid proteins, VP1 (1D), VP2 (1B), VP3 (1C), and VP4 (1D). VP1, VP2, and VP3, the larger capsid proteins, form the outer capsid surface, while their amino termini are intertwined on the inside of the protein shell. VP4 is found exclusively lining the interior surface of the capsid. VP1, VP2, and VP3 have a common picornavirus folding motif consisting of an eight-stranded, anti-parallel β-barrel with the sequences connecting the β-strands forming loops found on the exterior of the virion. These surface loops contain the major antibody neutralization sites for picornaviruses, including the cardioviruses (4, 9, 19).

A deep depression has been observed on the surfaces of human rhinoviruses (HRV) (13, 18, 29), the polioviruses (PV) (16), coxsackievirus B3 (25), and the cardioviruses mengovirus and TMEV (12, 21, 23), but not foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) (1). This surface depression forms a canyon around the icosahedral fivefold axes on the surfaces of HRV, PV, and coxsackievirus B3, but is a focal depression or pit on the cardioviruses, where the prominent VP1 loops I and II, which have no homology in the other picornaviruses, block the lateral extension of the pit (12, 21). Diverse experimental approaches have demonstrated that the canyons of HRV-14 (6), HRV-16 (26), HRV-2 (10), and PV1 (7, 8, 14) are involved in virion attachment to the host cell receptor. On the other hand, a conformational change in the pit was found when mengovirus crystals were grown in the presence of 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) or in ≤10 mM phosphate in physiological saline (pH 4.6) (17). This conformational change, which involved movement of the FMDV or GH loop in VP1 and the carboxy terminus of VP2, and rearrangement of the GH loop in VP3, was associated with loss of mengovirus binding to host cells (17). These observations indicate that the cardiovirus pit is involved in receptor attachment; however, this notion has never been systematically tested by pinpointing amino acids involved in receptor binding.

The pathogenesis of the less virulent BeAn strain has been intensively investigated, including the mapping of viral determinants responsible for persistent infection of mice. We therefore used BeAn virus to study the effect of site-specific mutation of selected pit amino acids on viral binding as well as other replicative functions. The TMEV pit, located in the center of the protomer, is composed of VP1 and VP3 residues and extends toward a large depression at the twofold axis (12). Four amino acids within the pit, 1091, 1153, 1225, and 3179, were selected for mutagenesis to evaluate their role in receptor attachment.

Radiolabeled-virus binding assays revealed that two of the mutant viruses, V1091I and P1153A, had dramatic binding differences, while all of the other characteristics evaluated for these two viruses were similar to the parental BeAn virus, indicating that these residue replacements primarily altered the binding phenotype. While R1125A also showed binding differences, its capsid stability and single-step growth kinetics were also changed, suggesting that this replacement had also affected viral processes distinct from receptor attachment. Substitutions in the VP3 GH loop did not alter the binding phenotype, suggesting that this surface loop is not directly involved in TMEV-receptor interaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus infections.

BHK-21 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 mg of streptomycin per ml, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 7.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 6.5 mg of tryptose phosphate broth (Gibco/BRL) per ml (hereafter DMEM medium) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Receptor-negative BHK-21 cells, designated R26, were selected by resistance to BeAn virus infection and were maintained as the parental BHK-21 cells (S. Hertzler and H. L. Lipton, unpublished data). Virus infections and plaque assays were carried out on monolayers that were 90% confluent and in DMEM medium containing 1% FBS. Viral plaques were assayed on BHK-21 monolayers in 35-mm multiwell plates, by staining with crystal violet after incubation for 4 days at 33°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere as previously described (30).

Strategy of site-specific amino acid mutation.

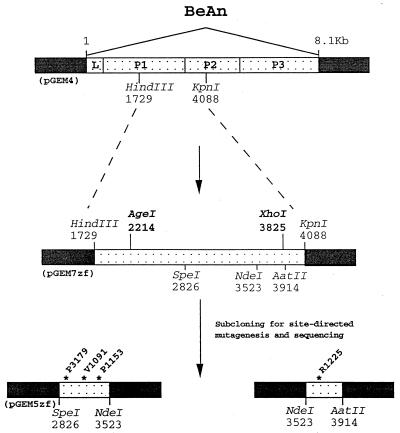

Mutant BeAn viruses were derived from a plasmid containing the full-length wild-type BeAn cDNA in pGEM4 (Promega), immediately downstream from the T7 RNA polymerase promoter (5) (Fig. 1). The plasmid had been modified so that only two nucleotides separated the T7 RNA polymerase promoter and the 5′ end of the virus, and an XbaI site was engineered immediately downstream of the poly(A) tract at the 3′ end. A 2.3-kb HindIII-KpnI (nucleotides 1729 to 4088) restriction fragment, spanning the VP1 (1D) and VP3 (1C) sequences and including all of the potential receptor binding or pit residues, was cloned into the HindIII-KpnI site of pGEM7zf(−). This subgenomic construct was used to assemble the full-length BeAn cDNA following site-directed mutagenesis, since it contains two unique restriction endonuclease sites, AgeI (nucleotide 2214) and XhoI (nucleotide 3825), flanking the VP1 and VP3 sequences. From this 2.3-kb subgenomic clone, two smaller restriction fragments, 0.7-kb SpeI-NdeI (nucleotides 2826 to 3523) and 0.3-kb NdeI-AatII (nucleotides 3523 to 3914), were cloned into pGEM5zf(+) to facilitate nucleotide sequencing after site-directed mutagenesis. A PCR-based method (15) and the primers listed in Table 1 were used to introduce nucleotide changes into the sequences of the following pit residues: V1091, P1153, R1225, and P3179. Deep Vent polymerase (New England Biolabs) was used in PCRs according to the manufacturer's instructions. The final PCR products were separated by electrophoresis, gel purified, and cloned into the SpeI-NdeI or NdeI-AatII restriction endonuclease sites in pGEM5zf(+). Dideoxynucleotide sequencing (Sequenase 2.0) confirmed the presence of the expected mutations and excluded the introduction of secondary mutations during PCR. After the nucleotide sequence was confirmed, the 0.7-kb SpeI-NdeI or 0.3-kb NdeI-AatII fragments replaced their parental counterparts in the BeAn HindIII-KpnI construct. Following restriction endonuclease digestion and gel purification, the 1.6-kb AgeI-XhoI restriction fragment replaced that in parental BeAn in pGEM4. Plasmids were grown in Escherichia coli DH5α cells.

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of BeAn cDNA constructs used in site-directed mutagenesis and assembly of infectious cDNA. Pit residues are indicated by an ∗; L is the leader protein; P1, P2, and P3 are the three coding parts of the genome.

TABLE 1.

Primers used to generate pit mutations

| Mutationa | Sequence of forward and reverse primers (5′→3′)b | Codon change |

|---|---|---|

| V1091I | CAAAGGCTCCCNNTCAATGGCGATG | GUU→AUU |

| CATCGCCATTGANNGGGAGCCTTTG | ||

| V1091G | CAAAGGCTCCCNNTCAATGGCGATG | GUU→GGU |

| CATCGCCATTGANNGGGAGCCTTTG | ||

| V1091D | CAAAGGCTCCCNNTCAATGGCGATG | GUU→GAU |

| CATCGCCATTGANNGGGAGCCTTTG | ||

| P1153A | TACCGGCGCCGCTGCGGATGT | CCU→GCU |

| ACATCCGCAGCGGCGCCGGTA | ||

| P1153T | CCTACCGGCGCCNNTGCGGATGTTAC | CCU→ACU |

| GTAACATCCGCANNGGCGCCGGTACC | ||

| P1153D | CCTACCGGCGCCNNTGCGGATGTTAC | CCU→GAU |

| GTAACATCCGCANNGGCGCCGGTACC | ||

| R1225A | CAGAGAGCCCCGAAGTCTGCGTT | CGU→GCU |

| AGACTTCGGGGCTCTCTGGATCC | ||

| R1225S | CCTGGATCCAGAGNNNCCCGAAGTCTGCGT | CGU→UCC |

| CGCAGACTTCGGGNNNCTCTGGATCCAGG | ||

| R1225E | CCTGGATCCAGAGNNNCCCGAAGTCTGCGT | CGU→GCU |

| CGCAGACTTCGGGNNNCTCTGGATCCAGG | ||

| P3179A | AGTTATACCAGCNNCACTATCACCTC | CCC→GCC |

| GAGGTGATAGTGNNGCTGGTATAACT | ||

| P3179T | AGTTATACCAGCNNCACTATCACCTC | CCC→ACC |

| GAGGTGATAGTGNNGCTGGTATAACT | ||

| P3179D | AGTTATACCAGCNNCACTATCACCTC | CCC→GAC |

| GAGGTGATAGTGNNGCTGGTATAACT |

The first letter is the parental amino acid, the first digit signifies the capsid protein, the next three digits identify the amino acid residue within the protein, and the last letter is the substituted amino acid.

Fourfold degeneracy exists at each nucleotide site labeled N.

In vitro transcription and transfection.

cDNA clones, oriented with the 5′ genomic end downstream of the T7 promoter, were linearized at the XbaI site within the vector immediately downstream of the virus poly(A) tail. Plus-strand RNA transcripts were synthesized in reaction mixtures that contained 100 U of T7 RNA polymerase and 1 μg of plasmid DNA as described previously (5). Subconfluent BHK-21 cell monolayers in 60-mm dishes were transfected with transcription reaction mixtures (5 μg of RNA) with Lipofectin (Gibco-BRL) as specified by the supplier. To amplify virus titers, progeny virus stocks were prepared after two additional passages in BHK-21 cells. Both cells and supernatants were harvested when there was >90% cytopathic effect and clarified supernatants were obtained by sonication of the cells on ice (two 30-s bursts at a no. 2 setting of a Branson sonifier) followed by low-speed centrifugation.

Dideoxynucleotide sequencing.

Total RNA isolated from BHK-21 cells infected with mutant virus stocks with TriZol reagent (Gibco) was reverse transcribed (1.2 μg of RNA in a 25-μl reaction mixture) with Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Gibco) in the presence of random primers (1.8 μM). Two microliters of each cDNA reaction was PCR amplified in a 50-μl reaction mixture with negative-strand and positive-strand primers equivalent to BeAn nucleotides 2753 to 3807. Gel-purified PCR products were sequenced using the ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems).

Single- and multistep virus growth kinetics.

BHK-21 cell monolayers were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 in 96-well plates (single step) or of 0.2 in 24-well dishes (multistep). Following adsorption for 45 min, monolayers were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, and incubated in DMEM medium supplemented with 1% FBS. At each time point, triplicate or quadruplicate wells were harvested and total virus yields were determined from the virus in the supernatant and that released by the freeze-thaw method. The growth kinetics for each virus was repeated at least two times.

Virus RNA replication.

BHK-21 cell monolayers were infected at an MOI of 10 in 96-well plates. Following virus adsorption for 45 min, monolayers were washed twice with PBS, and 100 μl of DMEM medium per well, containing 10 μCi of [3H]uridine per ml and 5 μg of actinomycin D per ml, was added. At each time point, quadruplicate wells were harvested with a PHD cell harvester (Cambridge Technology, Inc., Watertown, Mass.) onto glass fiber filters. Radioactivity was determined for the replicates with a Beckman LS5000TD scintillation counter, and the mean and standard deviation were calculated and graphed for each time point.

Thermal stability.

Virus samples containing 106 PFU/ml in 0.65-ml Eppendorf tubes were immersed in a 40°C water bath for the indicated times, removed, and immediately plunged into liquid nitrogen. Control samples (time zero) were transferred to liquid nitrogen immediately following pipetting to triplicate tubes. The amount of virus remaining at each time point was determined by plaque assay. Thermostability represents the percent decline in virus titer after heating at 40°C.

Virus purification.

Virus was purified as described (30) with modifications (20). Specifically, following virus adsorption, infected BHK-21 monolayers (in 100-mm dishes) were incubated in maintenance medium for 5 h at 33°C, washed twice with DMEM deficient in methionine and cysteine, and incubated in this medium for 45 min at 33°C, and then deficient DMEM medium containing 20 to 30 μCi of 35S-Trans label (ICN) per ml was added. Infection was allowed to progress to complete the cytopathic effect by 20 to 24 h postinfection. HEPES and MgCl2 were added to the cells and supernatant to concentrations of 25 mM and 20 mM, respectively, and bovine pancreatic DNase I (Sigma Chemical) was added to a concentration of 10 μg/ml, and the lysate was incubated for 30 min at 24°C. NaCl was added to 0.5 M and PEG-8000 to 10% (wt/vol) to the lysate, stirred for 1 h at 24°C, and centrifuged in a Beckman HB-6 rotor at 10,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. After resuspension of the pellet in high-salt TNE buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 0.5 M NaCl, 2 mM EDTA) (hereafter designated hsTNE), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and PEG-8000 were added to 1 and 10% (wt/vol), respectively, stirred for 1 h at 24°C, and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 30 min at 15°C. The pellet, resuspended in hsTNE containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol (2ME), and 1% (wt/vol) Sarkosyl, was layered over a 0.5-ml 30% sucrose cushion in hsTNE containing 1% BSA and centrifuged in a Beckman SW 50.1 rotor at 45,000 rpm for 90 min at 10°C. The pellet, resuspended in 2 ml of hsTNE containing 1% BSA, 0.1% 2ME, and 1% Sarkosyl, was layered on a 20 to 70% sucrose gradient in hsTNE and centrifuged in a SW41 rotor at 35,000 rpm for 3 h at 4°C. Gradients were fractionated from the bottom into 0.5-ml aliquots, and radioactivity was measured in a Beckman LS5000TD scintillation counter. The number of virus particles was determined from the virus RNA content measured at an optical density at 260 nm.

Estimation of physical particles.

To obtain an estimate of the infectious particle-to-physical particle ratio for the different viruses, we determined the TMEV RNA concentration of sucrose-gradient purified viruses. The number of physical particles was calculated assuming that 1 mg of picornavirus RNA is equivalent to 7.2 × 1013 virus genomes and to an equivalent number of virus particles (28). The number of physical particles was then related to the titer of the purified virus, as determined by a standard plaque assay.

Binding assay and estimation of the attachment rate constant.

BHK-21 cells were detached from monolayers with PBS without calcium and magnesium, washed, resuspended to a concentration of 106 cells/ml in DMEM containing 20 mM HEPES and 1% BSA, and incubated on ice for 1 h before the addition of [35S]methionine-labeled virus (20,000 particles/cell). At the indicated times, an aliquot of the virus-cell suspension was removed and diluted in DMEM containing 20 mM HEPES before centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 30 s. The supernatant and cell-associated radioactivity were determined for triplicate samples in a Beckman LS5000TD scintillation counter and plotted as the percentage of cell-associated counts.

This interaction was considered as a first-order reaction; therefore, the rate was measured from the initial slope of the curve with the equation K = 2.3 log (V0/V) Ct, where V0 is the total amount of virus particles added to 106 cells (C), and V is the unattached virus in a period of time (t). K represents the attachment rate constant for the formation of virus-cell complexes (11a, 28).

In vitro translation.

Translation reactions were carried out at 30°C in rabbit reticulocyte lysates with a TNT Coupled Transcription/Translation System (Promega) as specified by the supplier. The translation reaction was terminated after 5 h by transferring the sample tubes to −20°C or by the addition of Laemmli sample buffer. Samples containing [35S]methionine-labeled viral proteins were electrophoresed on 20% Ortec gels and exposed to Kodak X-OMAT AR film. Protein synthesis was quantitated in triplicate by trichloroacetic acid precipitation with precipitates collected on glass fiber filters, and radioactivity was measured in a Beckman LS5000TD scintillation counter.

RESULTS

Selection of pit residues for site-directed mutagenesis.

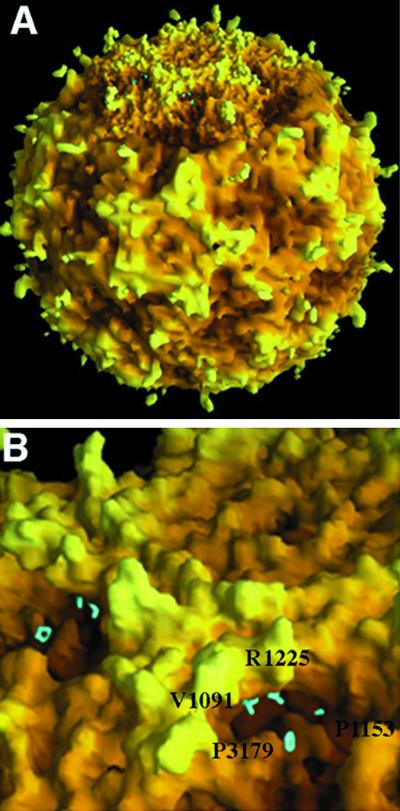

Pit residues at the contact region of VP1 and VP3 are located 140 to 150 Å from the center of the virus particle; roadmaps of the BeAn pit depicting the depression of the pit have been reported (32). Residues V1091, P1153, A1225, and P3179 were chosen for site-directed mutagenesis based on inspection of the atomic structures of BeAn, DA, and GDVII viruses and on comparison of these structures with HRV-14 complexed with its receptor (26, 29). The first digit of the residue identification signifies the viral protein, while the last three digits give the amino acid sequence number within the protein. The side chain of each selected residue, exposed within the pit, projects into the solvent space (Fig. 2), and the residues are located within a region homologous with the intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) footprint on the HRV-14 canyon (26). Interestingly, the BeAn virus atomic structure was originally modeled on the mengovirus coordinates except for VP2 puff B, since the mengovirus VP2 puff B is truncated by 11 residues compared to BeAn virus (27). However, we found that these residues could be modeled within the HRV-14 VP2 puff B coordinates (27). This indicates a similarity in structure in this region (near the pit) and provides a rationale for using the ICAM-1 footprint on the HRV-14 canyon to select BeAn virus pit residues.

FIG. 2.

Surface rendering with the program GRASP generated from the atomic coordinates of BeAn, showing BeAn virion with one pentamer in greater detail revealed at the top (A) and enlargement of the pit showing the side chains of the mutated residues (highlighted in cyan) projecting into the solvent space (B). R1225 and V1091 are slightly recessed beneath the northwest rim of the pit; P1153 is partially obscured in this view.

Stability and plaque morphology of the mutant viruses.

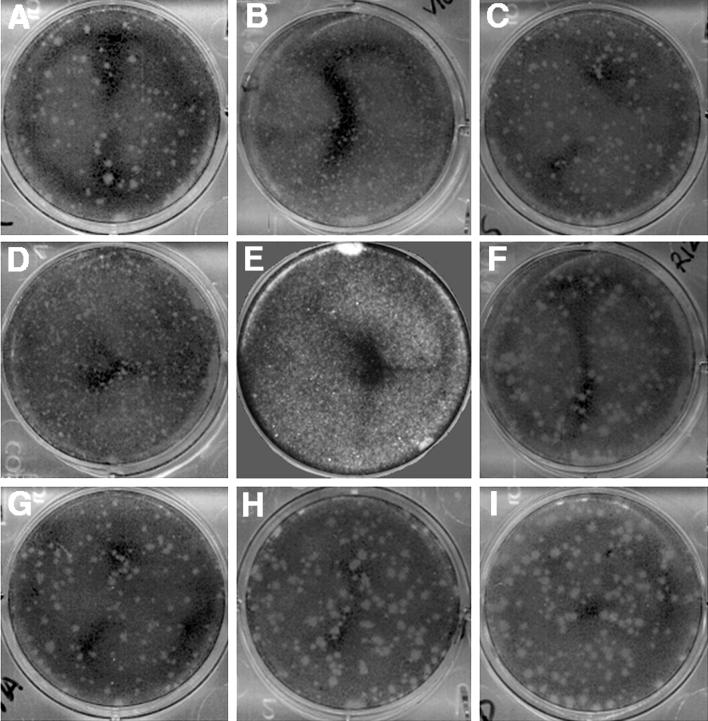

Each of the pit residues was initially mutated to a small nonpolar amino acid, alanine, except for residue 1091, which was mutated to an isoleucine. Since each of the four mutant viruses was infectious, two additional mutations were introduced into these sites. Thus, a total of 12 mutant BeAn viruses were generated, but when reassembled into full-length viral cDNA clones, only 8 of the mutant viruses yielded progeny virus upon transfection of BHK-21 cells. The four nonviable mutant viruses all represented more radical amino acid substitutions (Table 2). The sequence of the cDNAs prior to transfection confirmed the presence of the mutation and demonstrated the absence of mutations in the surrounding capsid sequences (see Materials and Methods). To confirm that each pit mutation was stable following transfection and two additional passages in BHK-21 cells, total RNA was isolated from the infected cells, reverse transcribed, and PCR amplified. The presence of the mutated residue was confirmed for all of the viable mutant viruses except V1091G, which had reverted to the parental codon. Compared to the BeAn parent, the seven viable mutants showed differences in plaque size and/or particle-to-PFU ratio (Table 2). Five of the seven mutants had a plaque morphology that differed from the parent, although not all had a smaller plaque phenotype (Fig. 3). P3179T and P3179D formed plaques that were 40 and 60% larger, respectively, than those of parental BeAn (Fig. 3).

TABLE 2.

Growth characteristics of parental BeAn virus and viruses with a single mutated pit residue

| Virus | Virus titer (PFU)a | Plaque size (mm) | Particle-to-PFU ratio ± SEM (n)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| BeAn parent | 2.0 × 108 | 1–2 | (3.19 ± 0.79) × 103 (5) |

| V1091I | 2.4 × 107 | <1 | (6.33 ± 1.9) × 103 (2) |

| V1091Gc | 9.0 × 107 | 1–2 | 5.50 × 103 |

| V1091D | NVd | ||

| P1153A | 2.2 × 107 | <1 | (1.38 ± 0.46) × 104 (2) |

| P1153T | NV | ||

| P1153D | NV | ||

| R1225A | 4.6 × 106 | <1 | 5.00 × 106 |

| R1225S | 1.4 × 107 | 3–4 | 1.29 × 104 |

| R1225E | NV | ||

| P3179A | 3.7 × 107 | 2–3 | 4.90 × 103 |

| P3179T | 4.6 × 108 | 3–4 | 3.56 × 103 |

| P3179D | 2.8 × 106 | 2–3 | 4.30 × 103 |

Titer of virus stocks derived by transfection and two subsequent BHK-21 cell passages.

The number of virus particles was calculated from the concentration of virus RNA molecules determined from the measurement of purified virions at an optical density of 260 nm/PFU. See Materials and Methods. SEM values were only presented for the viruses that were purified more than once.

V1091G had reverted to the wild type, as shown by sequencing.

NV, nonviable.

FIG. 3.

Plaque phenotypes of parental BeAn and mutant viruses. BHK-21 cell monolayers, infected with the viruses and overlaid with 1.6% Noble's agar in DMEM, were incubated at 33°C for 4 days and stained with crystal violet. A, parental BeAn; B, V1091I; C, V1091G; D, P1153A; E, R1225A; F, R1225S; G, P3179A; H, P3179T; I, P3179D. Mutants V1091D, P1153T, P1153D, and R1225E were nonviable.

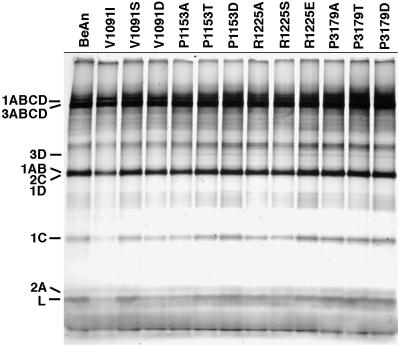

In vitro translation of viral RNAs.

Since the mutations were introduced into the capsid protein VP1 or VP3, the function of the nonstructural proteins, such as the viral polymerase (3D) and viral protease (3C), should not be directly affected. To rule out the possibility that the mutations might nevertheless induce a conformational change in the P1 precursor protein that might impair proteolytic processing by 3C, we tested the translational efficiency of the polyprotein in in vitro translation assays of viral RNA in rabbit reticulocyte lysates. Translation reactions were incubated for 5 h at 30°C, and aliquots of each reaction were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid to quantitate the level of total protein synthesis and analyzed on a 20% Ortec gel. Both the total amount of viral proteins synthesized (data not shown) and the pattern of processing of the viral polyprotein into the final gene products were similar to that of parental BeAn virus (Fig. 4). Thus, the fact that four of the mutant viruses were nonviable does not rest in a defect in polyprotein translation and proteolytic processing. Most likely, these viruses had a lethal mutation affecting capsid assembly.

FIG. 4.

In vitro translation of viral RNAs in rabbit reticulocytes, demonstrating that the processing and migration of the viral proteins of the mutant viruses, even the four that were nonviable, were identical to that of the parental BeAn virus. Samples were run on a 20% Ortec gel; the viral proteins are indicated.

Multistep growth kinetics of mutant viruses.

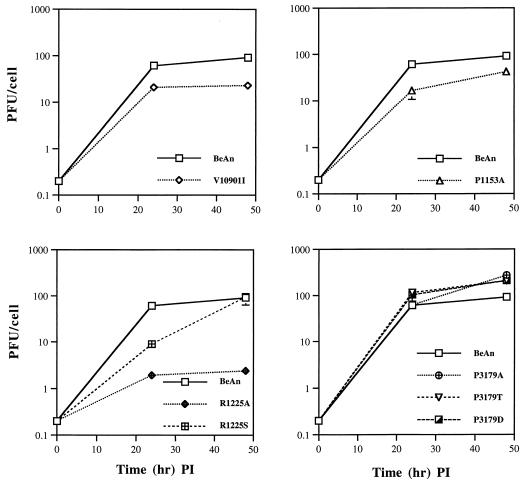

To analyze the growth characteristics of the mutant viruses, BHK-21 monolayers were infected at a low MOI (0.2), and virus yields were compared to that of the BeAn parent. Mutants V1091I, P1153A, and R1225A, which formed smaller plaques than BeAn, had reduced virus yields at 24 and 48 h, whereas mutants P3179T and P3179D, which formed slightly larger plaques than the parental virus, had greater virus yields than BeAn (Fig. 5). Mutant R1225S had a plaque size similar to that of the parental virus, showed delayed growth at 24 h, but reached parental levels at 48 h. Thus, all of the amino acid substitutions resulted in viruses with altered multistep growth kinetics.

FIG. 5.

Multistep growth kinetics of BeAn and mutant viruses. BHK-21 cell monolayers were infected with the indicated viruses at an MOI of 0.2 PFU/cell. Following adsorption at 24°C, virus was removed and the cells were washed and incubated in DMEM medium at 33°C. At 24 and 48 h, infected cells and supernatants were frozen and the viral titers were determined by plaque assay. Each point represents the mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) of triplicate samples. The zero time point represents the titer of the input virus. PI, postinfection.

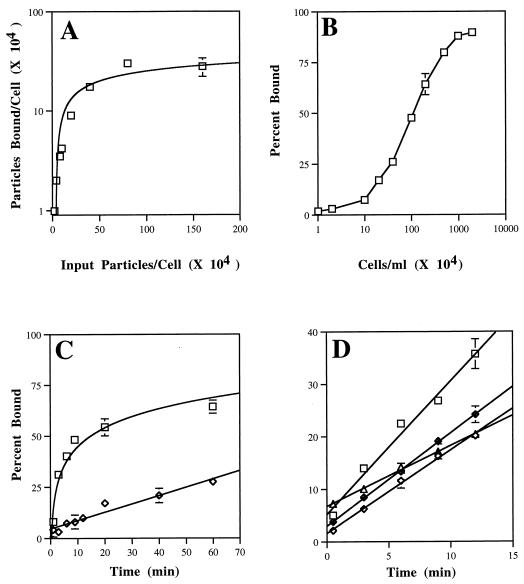

Viral binding of mutant viruses to BHK-21 cells.

To compare the cellular binding of mutant viruses to that of parental BeAn, the kinetics of association of these 35S-labeled viruses to BHK-21 cells in suspension was examined. Preliminary experiments revealed saturable binding of [35S]methionine-labeled BeAn virus to BHK-21 cells when increasing numbers of virions (Fig. 5) or cells, i.e., receptors (Fig. 5), were added. The association kinetics with subsaturating concentrations of virions was rapid, and binding reached a maximum within 30 min (Fig. 5). The association kinetics of the mutant viruses was determined using an equation of linear regression in the early portion of the curve, where nonspecific binding of the virus to a clonally derived BHK-21 receptor-negative cell line was <10% (Fig. 5) (S. Hertzler and H. L. Lipton, unpublished data). Comparison of the slopes of the linear regression analysis revealed reduced binding in three of the mutant viruses (V1091I, P1153A, and R1225A) (Fig. 5). Calculation of the attachment rate constants showed a significant difference for only these three mutant viruses (V1091I, P1153A, and R1225A) compared to BeAn virus (Table 3). No significant difference in binding was observed for the three VP3 179 GH loop mutants, and R1225S showed no difference in its binding compared to parental BeAn (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Kinetic binding constants for parental BeAn and mutant viruses

| Virus | Attachment rate constants ± SDa (cells/ml × min−1) | Significanceb |

|---|---|---|

| BeAn | (8.60 ± 1.05) × 10−8 | |

| V1091I | (1.31 ± 0.07) × 10−7 | <0.01 |

| P1153A | (1.36 ± 0.04) × 10−7 | <0.01 |

| R1225A | (1.21 ± 0.11) × 10−7 | <0.01 |

| R1225S | (9.26 ± 0.04) × 10−8 | >0.05 |

| P3179A | (1.00 ± 0.04) × 10−9 | >0.05 |

| P3179T | (1.05 ± 0.06) × 10−9 | >0.05 |

| P3179D | (8.96 ± 0.55) × 10−9 | >0.05 |

The results shown are representative of at least two independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Pairwise comparison of the attachment rate constants was by standard normal statistics (z test).

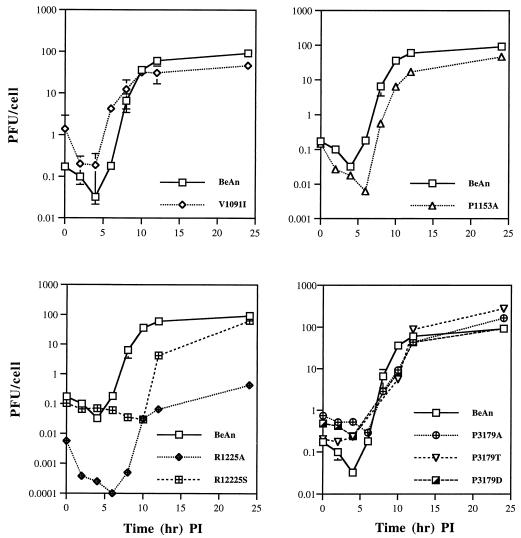

Single-step growth kinetics of mutant viruses.

To assess whether the amino acid substitutions affected viral processes distinct from receptor attachment, BHK-21 cells were infected at a high MOI (5 to 10) to compensate for differences in mutant virus binding (Fig. 6) and the single-step growth kinetics of the mutant viruses was compared to that of parental BeAn over 24 h. Due to the reduced titers for some of the mutant viruses (Table 2), it was not feasible to further increase the MOI of the single-step growth and RNA replication experiments. However, results from the RNA replication (see below) indicate that an MOI of 5 to 10 overcomes binding differences for V1091I, P1153A, and R1225A, as the kinetics and levels of [3H]uridine incorporation resemble those observed for parental BeAn. As shown in Fig. 7, all mutants were delayed in growth, particularly between 6 and 12 h, except for V1091I in which the kinetics of growth was faster in the early part of the curve (<6 h). Final virus yields were similar to that of parental virus for all of the mutants except R1225A, which was reduced by 2 log10 units. The three 3179 mutants all showed a shallow eclipse phase compared to the BeAn parent, suggestive of a defect in uncoating. These results suggest postattachment intracellular events were also affected by the amino acid replacements in all of the mutant viruses.

FIG. 6.

(A and B) Saturation analysis of [35S]methionine-labeled BeAn virus binding to BHK-21 cells. Increasing amounts of radiolabeled BeAn virus were incubated with 106 BHK-21 cells/ml (A), and increasing numbers of cells were incubated with a constant concentration of virus (2 × 104 particles/ml) (B). After 30 min at 4°C, the cell suspension was diluted fivefold in DMEM and pelleted in a 1.5-ml Eppendorf tube, and cell-associated radioactivity was determined. Results are expressed as virus particles bound/cell (A) or percentage of total radioactivity in the pellet fraction (B). Each point represents the mean and standard deviation (SD) of triplicate samples. (Error at most times was indiscernible.) (C) Association kinetics of BeAn virus to BHK-21 or TMEV receptor-negative BHK-R26 cells in suspension. [35S]methionine-labeled BeAn virus was incubated with 106 cells/ml at a particle-to-cell ratio of 20,000:1 at 4°C. At the indicated times, cell-associated radioactivity was determined. Results are expressed as the percentage of total radioactivity in the cell pellet fraction; each point represents the mean ± SEM of triplicate samples. □, BHK-21 cell binding; ◊, R26 cell binding. (D) Binding kinetics over 12 min for [35S]methionine-labeled BeAn (■) and mutant viruses (◊, V1091I; ▵, P1153A; ◊+, R1225A) assessed as described for panel C.

FIG. 7.

Single-step growth kinetics of BeAn and the mutant viruses. BHK-21 monolayers were incubated with virus (MOI, 5 to 10), and after adsorption at 24°C, the cells were washed, overlaid with DMEM maintenance medium, and incubated at 33°C. Cells and supernatants were harvested at the indicated times and the virus titers were determined by plaque assay. Zero time points represent the virus titers immediately following the adsorption period. SD bars are shown for BeAn and V1091I for triplicate independent growth curves. PI, postinfection.

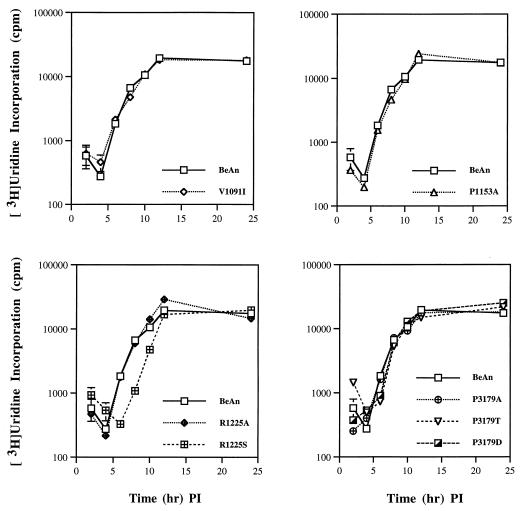

Viral RNA replication.

To determine whether the defects unrelated to receptor binding affected viral replication, viral RNA synthesis in BHK-21 cells infected at an MOI of 5 to 10 was measured over 12 h as the cumulative incorporation of [3H]uridine in the presence of actinomycin D. As shown in Fig. 8, the kinetics of viral RNA synthesis in the mutants was identical to that of BeAn and reached maximal levels by 12 h, except for R1225S and P3179T. Replication of R1225S was delayed by 3 h throughout most of the time course yet reached parental levels of isotope incorporation by 12 h. Both P3179T and P3179D were apparently delayed initially but reached parental levels of incorporation by 8 h. Since the three mutants did not differ from parental BeAn in binding to BHK-21 cells, they may have a defect in a step later than receptor attachment, such as in cell entry or uncoating.

FIG. 8.

Viral RNA synthesis for BeAn and mutant viruses. BHK-21 cell monolayers were incubated with virus (MOI, 5 to 10) and after adsorption at 24°C, cells were washed and incubated with DMEM containing 5 μg of actinomycin D per ml and 10 μCi of [3H]uridine per ml at 33°C. Cells were harvested at the indicated times and the total incorporated radioactivity was determined and expressed as counts per minute. Each point represents the mean ± SEM of quadruplicate samples; the error bars are not discernible where the values are tightly clustered. PI, postinfection.

Heat stability.

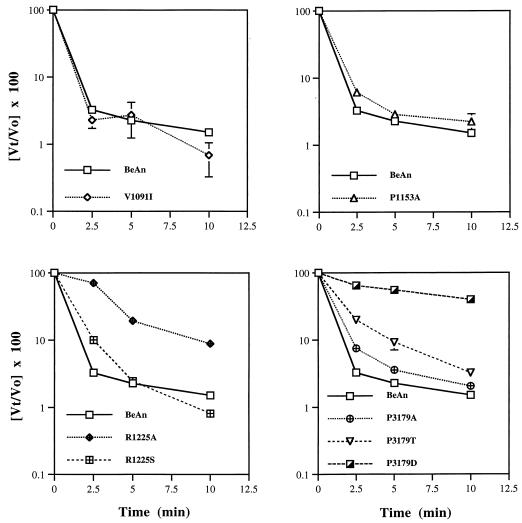

To assess the effect of the amino acid replacements on capsid stability, the titer of the mutant viruses was determined following heating to 40°C. Parental BeAn was quite thermolabile, with a loss of >90% of the titer at 40°C by 10 min; therefore, this temperature was used to determine the kinetics of thermal inactivation of the mutant viruses (Fig. 9). Substitutions at P3179 led to an increasingly more stable virion as the replacement proceeded from conservative (P3179A) to more radical amino acid (P3179D) replacements, with the phenotype of P3179T showing intermediate values. Substitutions at R1225 also resulted in a more heat-stable phenotype, most noticeably when the positively charged arginine was replaced with the nonpolar alanine. Substitution with the polar serine at this location resulted in a heat stability curve which was less steep, i.e., more heat-stable, during the first half of the time course, but then falling to the parental level of infectivity during the latter half of the time course. Substitutions at V1091 and P1153 had no effect on heat stability of these mutant viruses.

FIG. 9.

Stability of BeAn and mutant viruses to thermal inactivation. Each virus was diluted to 106 PFU/ml in DMEM and incubated at 40°C. At the indicated times, samples were removed and the virus titer remaining was measured by plaque assay. Each point represents the mean and SEM of triplicate samples; the error bars are not discernible where the values are tightly clustered.

DISCUSSION

We have taken a direct approach to determine whether the TMEV pit interacts with the host cellular receptor by evaluating the effect of specific amino acid changes on binding as well as on the subsequent steps in the life cycle of the mutant viruses. Based on inspection of the crystallographic structures of three TMEV strains solved to an atomic level (12, 21, 22) and a comparison with HRV-14 complexed with its receptor, ICAM-1 (26, 29), we introduced a series of single amino acid changes into a region within and on the west wall of the pit that is likely to encompass the receptor footprint. Previously, site-directed mutagenesis of HRV-14 indicated that substitution of four residues (1103, 1220, 1223 and 1273) in the floor of the canyon altered the binding affinity of HRV-14 to HeLa cell membranes (6). In addition, Harber et al. (14) found that PV1 Mahoney viruses with mutation of canyon residues 1089, 1166, and 1226 were greatly diminished in their ability to bind to the wild-type human poliovirus receptor. Similar studies to map the receptor binding sites on the surfaces of HRV-1A and coxsackievirus 9A by site-directed mutagenesis have recently been reported (A. Reischl and D. Blass, Abstr. 10th Meet. Eur. Study Group on Mol. Biol. Picornaviruses, p82, 1998, and C. H. Williams, P. J. Hughes, and G. Stanway, Abstr. 10th Meet. Eur. Study Group on Mol. Biol. Picornaviruses, p107, 1999).

Mutation of three VP1 pit residues alters BeAn virus binding.

Our results suggest that the three VP1 amino acids which were mutated (V1091, P1153, and A1225) are directly involved in BeAn virus binding to the cellular receptor on BHK-21 cells. These mutations probably alter the shape of the binding site and/or remove contact points for the receptor residues.

Residue V1091.

The most conservative mutation, V1091I, resulted in a mutant virus with decreased binding affinity for BHK-21 cells, while the other steps in the viral life cycle were not impaired. The small plaque phenotype and reduced virus yields obtained in the multistep growth experiment likely reflect impaired receptor attachment of the mutant virus. When glycine was substituted at this site (V109G), the mutant virus reverted to the parental sequence at this codon (GUU→GGU), following transfection of BHK-21 cells on two occasions. Substitution of the negatively charged aspartic acid (V1091D) was lethal, further supporting the notion that residue 1091 is critical in virus-receptor interaction. V1091 is located in the middle of a hydrophobic pocket, with its side chain exposed at the virion surface. While the V1091I mutation only modestly altered the hydrophobic environment, substitution of the negatively charged residue V1091D may have created new interactions with one of its nearest neighbors, R1225, in turn inducing a lethal conformational change near the boundary of VP1 and VP3, which are on neighboring protomers. V1091D might also have severely disrupted the receptor interaction so that a viable virus could not be recovered.

Residue P1153.

Residue P1153 was also sensitive to substitutions, since replacing one nonpolar residue with another, P1153A, produced a mutant with a drastically reduced binding affinity to BHK-21 cells compared to the parent. While the single-step growth kinetics was slightly delayed, viral RNA replication was normal, localizing the nonattachment defect(s) for P1153A to a step after binding but before RNA replication. We were unable to recover progeny virus from the cDNAs with two other substitutions, P1153T and P1153D, despite repeated transfection attempts. While P1153T and P1153D most likely had such severely disrupted receptor interactions that viral binding was completely abolished, a lethal effect on virion assembly cannot be excluded.

Residue R1225.

Substitution of the positively charged R1225 with alanine gave rise to a virus with reduced binding and with dramatically delayed single-step growth kinetics, indicating that intracellular events were also affected. Viral RNA replication kinetics indicated that most of the nonbinding phenotypic change resulting from this replacement occurred at a step prior to RNA replication, probably at the level of cell entry and/or viral uncoating. R1225A showed increased thermal stability, raising the possibility that as the capsid became more rigid and resistant to heat inactivation, the virus was less able to undergo the structural transition required for uncoating. In mutant R1225S, binding did not differ from that of the parent; however, both single-step growth kinetics and RNA replication were markedly delayed. Together, these data suggest that the mutation of R1225A and R1225S altered the conformation of the pit and receptor binding, as well as uncoating and assembly transitions.

Mutation of pit residue P3179 does not alter BeAn virus binding.

Atomic resolution of the BeAn virus crystal structure revealed close similarity to Mengovirus, another member of the Cardiovirus genus (21). Conditions in mengovirus crystals that order the GH loop in VP3 also correspond to those that permit the virus to bind to and infect cells. These data suggested a role for the pit in receptor binding for the cardioviruses, and more specifically, localized a critical region of the pit to the VP3 GH loop (17). Therefore, the role of the TMEV VP3 GH loop in receptor binding was investigated by mutating residue P3179; however, none of the replacements altered the binding phenotype of BeAn virus. Although small differences were observed in the growth characteristics of these viruses compared to parental BeAn, the most dramatic change was an increase in thermal stability. Even the conservative substitution of an alanine resulted in a stability phenotype that was intermediate between those of parental BeAn and the mutants with polar (P3179T) and charged polar (P3179D) substitutions at this site.

Temperature-sensitive (ts) PV mutants have been described (11, 24). The majority of Sabin 3 ts suppressors and all of the soluble receptor-resistant mutants (7) map to the interface between protomers. The stability of the protomer interface is believed to regulate structural transitions of the Sabin 3 strain during assembly. One ts suppressor and one soluble receptor-resistant mutant have the identical codon change at the same position, Q3178L (7, 24), suggesting that capsid alterations and receptor binding have a common structural basis. When the antiviral WIN compounds bind in the hydrophobic pocket of HRV and prevent uncoating, several residues at the carboxyl end of VP1 are displaced towards the protomer interface (3, 31). This creates more extensive interactions between the GH loops of VP1 and VP3, which act to stabilize the protomeric interface.

In the present study, we found that mutation of a single residue in VP3 resulted in a virus with an increased plaque size and a thermostable phenotype. In the chimeras described by Adami et al. (2), none exclusively replaced the BeAn VP3 with the GDVII protein, although one of the chimeras contained both GDVII VP1 and VP3 in a BeAn background; plaque sizes for this virus were three to four times larger and thermal stability was greater than in the chimera in which only VP1 was replaced. However, this chimera was much more compromised in its single-step growth kinetics. Similarly, P3179D, which produced large plaques but was heat stable, produced a larger yield of virus than parental BeAn (Table 1). By analogy with the rhinoviruses, mutations in the BeAn VP3 GH loop might lead to conformational changes that stabilize the interaction between the GH loop of VP1 and VP3 at the protomer interface, creating a capsid structure which uncoats less efficiently. Together, these data indicate that a balance exists between structural stability and the conformational flexibility needed for uncoating and virion assembly.

In summary, the altered binding phenotypes of the three VP1 pit mutant viruses provide evidence that the pit is involved in TMEV-receptor interaction. Additional mutagenesis studies, and most importantly, identification of the cellular receptor for TMEV followed by structural analysis of the virus-receptor complex, will be needed for a more complete picture of TMEV-receptor interactions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Chris Pasko for technical assistance and Kathy Rundell and Pat Spear for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by NIH grant NS23249 and The Leiper Trust.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acharya R, Fry E, Stuart D, Fox G, Rowlands D, Brown F. The three-dimensional structure of foot-and-mouth disease virus at 2.9 A resolution. Nature. 1989;327:709–716. doi: 10.1038/337709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adami C, Pritchard A E, Knauf T, Luo M, Lipton H L. Mapping a determinant for central nervous system persistence in the capsid of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) with recombinant viruses. J Virol. 1997;71:1662–1665. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1662-1665.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badger J, Minor I, Kremer M J, Smith T J, Griffith J P, Guerin D M, Krishnaswamy S, Luo M, Rossmann M G. Structural analysis of a series of antiviral agents complexes with human rhinovirus 14. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:3308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.10.3304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boege U, Kobasa D, Onodera S, Parks G D, Palmenberg A C, Scraba D G. Characterization of Mengo virus neutralization epitopes. Virology. 1991;181:1–13. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90464-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calenoff M A, Faaberg K S, Lipton H L. Genomic regions of neurovirulence and attenuation in Theiler's murine encephalo-myelitis virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:978–982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.3.978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colonno R J, Condra J H, Mizutani S, Pia L, Davies M-E, Murcko M A. Evidence for the direct involvement of the rhinovirus canyon in receptor binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5449–5453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colston E, Racaniello V R. Soluble receptor-resistant polio-virus mutants identify surface and internal capsid residues that control interaction with the cell receptor. EMBO J. 1994;13:5855–5862. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06930.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colston E M, Racaniello V R. Poliovirus variants selected on mutant receptor-expressing cells identify capsid residues that expand receptor recognition. J Virol. 1995;69:4823–4829. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4823-4829.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crane M A, Jue C, Mitchell M, Lipton H, Kim B S. Detection of restricted predominant epitopes of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus capsid proteins expressed in the lambda gt11 system: differential patterns of antibody reactivity among different mouse strains. J Neuroimmunol. 1990;27:173–186. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(90)90067-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duechler M, Ketter S, Skern T, Kuechler E, Blaas D. Rhinoviral receptor discrimination: mutational changes in the canyon regions of human rhinovirus types 2 and 14 indicate a different site of interaction. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:2287–2291. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-10-2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filman D J, Syed R, Chow M, Macadam A J, Minor P D, Hogle J M. Structural factors that control conformational transitions and serotype specificity in type 3 poliovirus. EMBO J. 1989;8:1567–1579. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Fotiatdis C, Kilpatrick D R, Lipton H L. Comparison of binding characteristics to BHK-21 cells of viruses representing the two Theiler's virus neurovirulence groups. Virology. 1991;182:365–370. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90683-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grant R A, Filman D J, Fujinami R S, Icenogle J P, Hogle J M. Three-dimensional structure of Theiler's virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2061–2065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hadfield A T, Lee W-M, Zhao R, Oliveira M A, Minor I, Rueckert R R, Rossmann M G. The refined structure of human rhinovirus 16 at 2.15 A resolution: implications for the viral life cycle. Structure. 1997;5:427–441. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00199-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harber J, Bernhardt G, Lu H H, Sgro J-Y, Wimmer E. Canyon rim residues, including antigenic determinants, modulate serotype-specific binding of polioviruses to mutants of the poliovirus receptor. Virology. 1995;214:559–570. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higuchi R, Krummel B, Saiki R K. A general method of in vitro preparation and specific mutagenesis of DNA fragments: study of protein and DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:7351–7367. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.15.7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hogle J M, Chow M, Filman D J. Three-dimensional structure of poliovirus at 2.9 A resolution. Science. 1985;229:1358–1365. doi: 10.1126/science.2994218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim S, Boege U, Krishnaswamy S, Minor I, Smith T J, Luo M, Scraba D G, Rossmann M G. Conformational variability of a picornavirus capsid: pH-dependent structural changes of Mengo virus related to its host receptor attachment site and disassembly. Virology. 1990;175:176–190. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90198-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim S, Smith T J, Chapman M S, Rossmann M G, Pevear D C, Dutko F J, Felock P J, Diana G D, McKinlay M A. Crystal structure of human rhinovirus serotype 1A (HRV1A) J Mol Biol. 1989;210:91–111. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90293-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobasa D, Mulvey M, Lee J S, Scraba D G. Characterization of Mengo virus neutralization epitopes. II. Infection of mice with an attenuated virus. Virology. 1995;214:118–127. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.9948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipton H L, Friedmann A. Purification of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus and analysis of structural virion polypeptides. Correlation of structural polypeptide composition with virulence. J Virol. 1980;33:1165–1172. doi: 10.1128/jvi.33.3.1165-1172.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo M, He C, Toth K S, Zhang C X, Lipton H L. Three-dimensional structure of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (BeAn strain) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2409–2413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo M, Toth K S, Zhou L, Pritchard A, Lipton H L. The structure of a highly virulent Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (GDVII) and implications for determinants of viral persistence. Virology. 1995;220:246–250. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo M, Vriend G, Kamer G, Minor I, Arnold E, Rossmann M G, Boege U, Scraba D G, Duke G M, Palmenberg A C. The atomic structure of Mengo virus at 3.0 A resolution. Science. 1987;235:182–191. doi: 10.1126/science.3026048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minor P D, Dunn G, Evans D, Magrath D I, John A, Howlett J, Phillips A, Westrop G, Wareham K, Almond J W, Hogle J M. The temperature sensitivity of the Sabin type 3 strain of poliovirus: molecular and structural effects of a mutation in the capsid protein VP3. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:1117–1123. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-5-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muckelbauer J K, Kremer M, Minor I, Diana G, Dutko F J, Groarke J, Pevear D C, Rossmann M G. The structure of coxsackievirus B3 at 3.5 A resolution. Structure. 1999;3:653–667. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olson N H, Kolatkar P R, Oliveira M S, Cheng R H, Greve J M, McClelland A, Baker T S, Rossmann M G. Structure of a human rhinovirus complexed with its receptor molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:507–511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pevear D C, Luo M, Lipton H L. Three-dimensional model of the capsid proteins of two biologically different Theiler's virus strains: clustering of amino acid differences identifies possible locations of immunogenic sites of the virion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4496–4500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rueckert R R. Picornaviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D N, Howley P M, Chanock R M, Melnick J L, Monath T P, Roizman B, Straus S E, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y: Lippincott-Raven Press; 1996. pp. 609–654. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rossmann M G, Arnold E, Erickson J W, Frankenberger E A, Griffith J P, Hecht H-J, Johnson J E, Kamer G, Luo M, Mosser A G, Rueckert R R, Sherry B, Vriend G. Structure of a human common cold virus and functional relationship to other picornaviruses. Nature. 1985;317:145–153. doi: 10.1038/317145a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rozhon E J, Kratochvil J D, Lipton H L. Analysis of genetic variation in Theiler's virus during persistent infection in the mouse central nervous system. Virology. 1983;128:16–32. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90315-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith T J, Kremer M, Luo M, Vriend G, Arnold E, Kamer G, Rossmann M G, McKinlay M A, Diana G, Otto M J. The site of attachment in human rhinovirus 14 for antiviral agents that inhibit uncoating. Science. 1986;233:1286–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.3018924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou L, Lin X, Green T J, Lipton H L, Luo M. Role of sialyloligosaccharide binding in Theiler's virus persistence. J Virol. 1997;71:9701–9712. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9701-9712.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]