The past 200 years have witnessed a revolution in global fertility, mortality, and population growth rates, in which the demography and health of human populations have been transformed. Vast gender and geographical inequalities in income and health persist, and new threats such as HIV/AIDS, environmental degradation, and population ageing have emerged. In July a special session of the United Nations General Assembly met to consider global progress in implementing the programme of action agreed at the 1994 international conference on population and development in Cairo.1 It approved far reaching recommendations for dealing with global trends in reproductive health and population.

This article reviews the transition in world health and population, and considers the changes that lie ahead. The economic and environmental implications of changes in the size, structure, and consumption patterns of world population are discussed in the other papers in this issue.

Summary points

More people were added to the world’s population in the past 50 years than in the preceding million, and world population is expected to reach about 9 billion by 2050

Substantial growth in world population during the next century is inevitable because, although world fertility is lower than ever before, the high fertility of previous generations means that growing cohorts of future parents are already born

The largest increases in world population will occur in countries where poverty and unemployment are endemic, with Africa’s share rising from 13% to 22% by 2050

All regions will experience population ageing: the number of people aged 60 and over will increase fourfold by 2050, their proportion rising from 9% of the total to 21%

Population policies will need to address the socioeconomic and environmental implications of changes in the size, structure, and consumption patterns of world population, and the emerging task of achieving a sustainable and equitable global human ecology

Methods

This review is based on material drawn from United Nations and World Health Organisation publications, information on the special session of the United Nations General Assembly in July 1999 supplied by the Department for International Development, books, and searches on Medline and Popline.

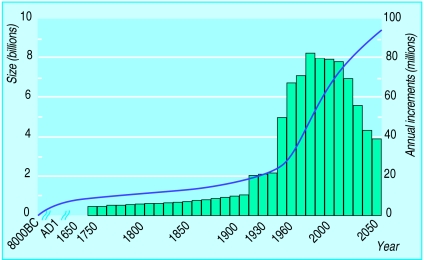

Malthusian principles

From the origins of Homo sapiens, about a quarter of a million years ago, to 1800 AD, world population increased by only 1 billion. The next 5 billion were added in just 200 years, the latest billion taking just 12 years to accrue (fig 1). Although the writings of Reverend Thomas Malthus, whose First Essay on Population was published in 1798,2 predate the phase of fastest growth in world population, Malthusian principles continue to dominate the population debate. Malthus’s thesis was that the potential of population to grow exponentially, and hence faster than resources, would compromise human welfare unless controlled by “positive checks,” such as disease, famine, and war, or “preventive checks,” by which (in the absence of contraception) he meant restrictions on marriage.

Figure 1.

World population size (line) and annual increments (bars), 8000 BC to 2050 AD

The demographic transition

The environmental limits to demographic expansion in Europe lifted with the industrial and technological revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries, supplemented by the gains from distant colonisation. Declining mortality in Europe and fast population increase in America brought sustained growth in world population from 1750.3 Around the same time, a fertility decline began in France and spread throughout the rest of Europe (largely brought about by the use of coitus interruptus).3–5

In the developed world the demographic transition from high birth and death rates to low ones spanned two centuries, whereas in the developing world (where it is not yet complete) it has so far taken 50 years. Public health measures, famine control, and the modern availability of drugs and vaccines led to precipitous falls in mortality in much of the developing world, where life expectancy now averages 64 years.6,7 But the gains have not been uniform: life expectancy in some sub-Saharan countries is only 40 years.

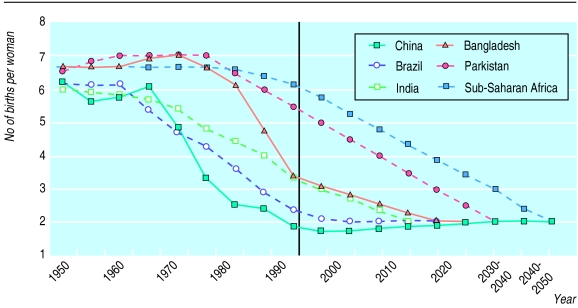

The rapid population growth that followed prompted many governments, primarily in Asia, to adopt policies to reduce fertility. In many countries, fertility was already slowing down, but governments and internationally assisted family planning programmes have played a key role in accelerating reproductive change. The most spectacular example is that of the one child policy in China, where births per woman fell from six to two in two decades, a demographic change that took 150 years in Europe.7,8 But state intervention does not have to be coercive to achieve demographic goals. Bangladesh, where births per woman have fallen from almost seven in the 1970s to three in 1998, demonstrates that effective public provision of contraception can, even in exceedingly poor societies, reduce fertility dramatically.9 Fertility is now declining in virtually all developing countries, where it averages three births per woman compared with double that number mid-century, but there is enormous diversity, even between neighbouring countries (fig 2).

Figure 2.

Past and projected birth rate in selected developing countries and regions

The rapid fall in mortality in the developing world, with lowered birth rateslagging behind, led to the boom in world population after the second world war (fig1). Although the tide has turned and the 1990s herald a slowing down of growth in world population, world population is still increasing by 80 million a year.

The epidemiological transition

The global demographic transition is leading inexorably to an epidemiological transition6 and a double burden of disease, as described by the World Health Organisation. One element is the growing burden of non-communicable disease—in both developed and developing countries—as a consequence of population ageing. Cardiovascular disease, cancer, neuropsychiatric conditions, and injury are fast becoming the leading causes of disability and premature death in most regions. The other burden arises from communicable diseases, which still cause high levels of morbidity and mortality in developing countries.

Ill health among poor women and children constitutes a large proportion of the incomplete transition in health.1,6,10,11 Two million children die from diseases that could be prevented by vaccines, 7.5 million die in the perinatal period (primarily because of poor health care for mothers), and 200 million are malnourished. Unmet demand for contraception and unwanted childbearing are major problems: 200 million poor people lack access to contraception,1,6,11 and the 30 million abortions each year in developing countries, which account for 10-30% of overall fertility control,12 are a major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. About 600 000 women die each year from causes related to pregnancy and childbirth, most in poor countries, where the lifetime risk of maternal mortality is 250 times that of rich countries.6,13 These concerns explain the shifting focus, initiated at Cairo in 1994 and reaffirmed this year by the United Nations General Assembly, of population policies from family planning to the broader agenda of reproductive health.

This strategic shift has been reinforced by trends in sexually transmitted diseases, HIV/AIDS in particular, which has had a far greater spread and impact than was foreseen at the 1994 Cairo conference. Of the 54 million deaths annually in the world, 1 million are from malaria, 1.5 million (many of them related to HIV) from tuberculosis, and 2.3 million are from AIDS—now the leading cause of infectious disease mortality and fourth leading cause of death after coronary heart disease, stroke, and acute respiratory infection.6,14 In Africa, where HIV/AIDS is the leading cause of death, it has had devastating health, demographic, and economic effects in the worst affected regions—notably sub-Saharan Africa, where the probability of dying between ages 15 and 60 has more than doubled.15 Because most AIDS victims are young adults or infants infected by mother to child transmission, the virus has reduced life expectancy in the worst affected countries by up to 28 years, wiping out the health gains of the previous half century.7 Some experts are concerned that the epidemic may be replicated in south and south east Asia.16

Future trends in population

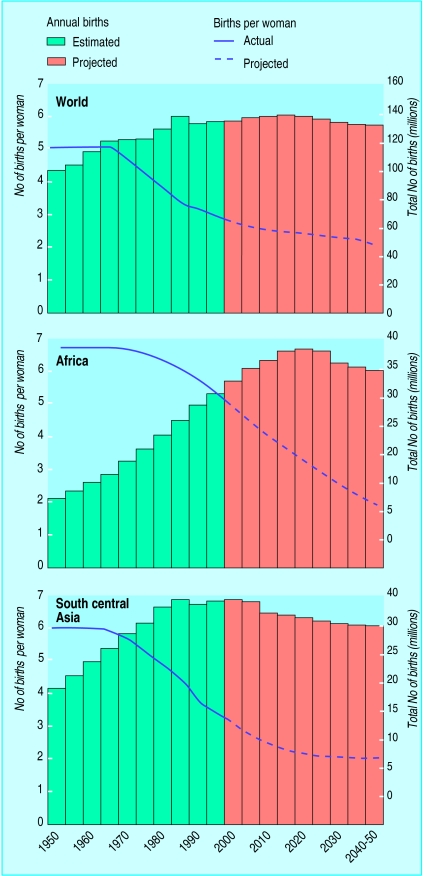

Based on varying assumptions about the future course of fertility, projections by the United Nationsestimate world population in the range of 7.7 billion to 11.2 billion in 2050. Substantial growth in world population during the next half century is inevitable, because the momentum for it has already been generated.7,17,18 Although women today are having fewer babies than ever before, the high fertility of previous generations means that growing cohorts of future parents are already born. Hence there were almost 20% more births worldwide in the 1990s than in the 1960s, even though individual fertility was 40% lower (fig 3).7 Because the number of births per woman in Africa has been slow to decline, birth rates there will continue increasing well after they have stabilised elsewhere, as in south Asia. The decline in individual fertility will not result in fewer annual births globally until after 2025, and world population is not expected to stabilise until about 2100. The pace of decline in birth rates in regions where fertility has been relatively resistant to change, as in sub-Saharan Africa, will be the most important determinant of future population size (fig 3).7,11 Although the steep mortality increase in Africa because of AIDS introduces great uncertainty over the future course of birth rates in this region, populations even in the worst affected countries are expected to triple by 2050 because of high rates historically.7

Figure 3.

Number of births per woman (line) and estimated births per year in region (bars), 1950-2050

Perhaps the greatest challenges to human welfare in the future will come not so much from a growing world population as from some of the changes in population structure that lie ahead:

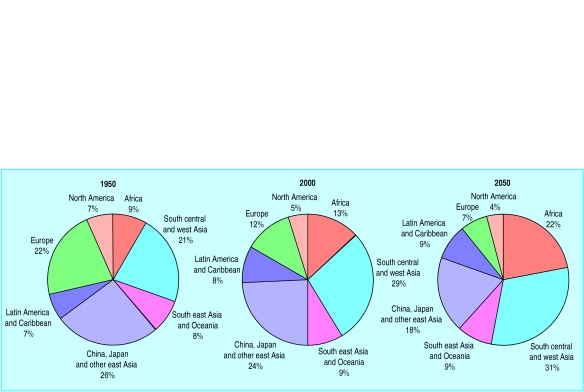

97% of future population growth will occur in developing countries. Because of its high birth rate and late demographic transition, Africa’s share of world population will rise from 13% to 22% by 2050 (fig 4)7

The largest increases in world population will occur in regions where poverty and unemployment are endemic7,11,18

With births per woman below replacement level in virtually all of Europe, population will decline and Europe’s share of world population will fall from 12% to 7% by 2050. In eastern Europe population has already started to fall, because of sharply declining birth rates combined with rising mortality in a number of countries, notably Russia, where male life expectancy in the 1990s has fallen by six years to 587,19

Falling birth rates and increased longevity will lead to ageing populations everywhere and to greatly increased demands for health and social security provision. The number of people aged 60 and over will increase fourfold by 2050, their proportion rising from 9% of total population to 21%.7,17 For developing countries, managing the disease burden of poverty alongside the growing burden of non-communicable disease will bring enormous and uncharted pressures on healthcare systems and resources

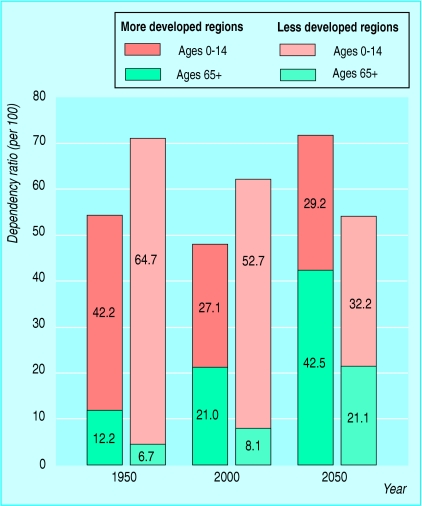

In developed regions, ageing will bring a significant rise in the ratio of children and elderly to population of working ages (fig 5). In contrast, demographic change in developing countries will result in large increases in their populations of working ages, and hence reduce the overall dependency ratio. The economic potential of this structural shift will depend on employment prospects for the expanding, largely unskilled workforces of countries already facing high levels of unemployment and poverty18

Rapid urbanisation means that by 2030 urban populations are likely to be twice the size of rural populations.11

Figure 4.

Geographical distribution of world population

Figure 5.

Dependency ratios in more developed regions (North America, Europe, Japan, Australia, New Zealand) and less developed regions (Africa, Latin America, Asia (excluding Japan))

The international response

The 1994 international conference on population and development in Cairo was an important milestone in extending the population debate, and national and international population policies, beyond their demographic focus to encompass the broader issues of reproductive health and rights. The special session of the United Nations General Assembly held in July this year to consider global progress since the international conference reaffirmed this stance, but recognised the need for bolder action to tackle trends (as in HIV/AIDS) in the post-Cairo era. For both conferences the priority has been the issue of population growth in poor countries where high birth rates, poor maternal and child health, sexually transmitted diseases, abortion, unmet contraceptive needs, and sex inequalities are major obstacles to development, rather than the long term structural changes in population that lie ahead.

The special session of the General Assembly called for a reversal of the decline in international assistance for population and reproductive health programmes, and universal access to reproductive health care and the widest possible range of contraceptive methods. With a larger world cohort of adolescents than ever before, and increasing and earlier exposure to sexual relations, unwanted pregnancy, and sexually transmitted diseases, its focus was primarily on young people. Some of the recommendations approved by the 180 nations that were represented drew vehement opposition from the Vatican, pro-life groups, and some conservative Muslim and Roman Catholic countries and were approved only after protracted, behind the scenes negotiations (in which Britain played a key part)—for instance, the recommendation for comprehensive reproductive and sexual health education and services for the 1 billion young people aged 14-25, including those who are not married.20 Even more contentious was the recommendation for unrestricted access to safe abortion in countries where abortion is legal.

Conclusion

This UN manifesto1 provides a challenge to international agencies, donors, and national governments to give leadership in programmes that are vital for both stabilising population growth and securing reproductive health and choice for all. With the global demographic transition now well underway, along with other social and economic changes, there will be a continuing need to develop and implement population policy in relation to the changing conditions of human societies. Population policy will need to be better integrated into the emerging task of achieving a sustainable and equitable global human ecology.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.United Nations. Report of the ad hoc committee of the whole of the twenty-first special session of the General Assembly: key actions for the further implementation of the international conference on population and development. New York: United Nations; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malthus TR. First essay on population [1798]. New York: AM Kelly; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Livi-Bacci M. A concise history of world population. Oxford: Blackwell; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crook N. Principles of population and development. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van de Walle E, Muhsam HV. Fatal secrets and the French fertility transition. Population and Development Review. 1995;21:261–279. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organisation. The world health report 1999: making a difference. Geneva: WHO; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 7.United Nations. World population prospects: the 1996 revision. New York: United Nations; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee J, Feng W. Malthusian models and Chinese realities: the Chinese demographic system 1700-2000. Population and Development Review. 1999;25:33–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.1999.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleland J, Lush L. Population and policies in Bangladesh, Pakistan. Forum for Applied Research and Public Policy. 1997;12:46–50. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organisation. The world health report 1998: life in the 21st century—a vision for all. Geneva: WHO; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Bank Group. Health, nutrition and population: sector strategy. The human development network. Washington DC: World Bank; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frejka T. International Population Conference, Montreal 1993. Vol. 1. Liege: International Union for the Scientific Study of Population; 1993. The role of induced abortion in contemporary fertility regulation: overview. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Department for International Development. International health matters: reproductive and sexual health. London: Department For International Development, June; 1999. (Issue 4.) [Google Scholar]

- 14.UNAIDS. Report on the global HIV/AIDS epidemic. New York: United Nations; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Timaeus I. Impact of the HIV epidemic on mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: evidence from national surveys and censuses. AIDS. 1998;12(suppl):S15–S27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adler M. AIDS isn’t over for everybody. Times 1999 July 30.

- 17.Lutz W, editor. The future population of the world: what can we assume today? International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis. London: Earthscan Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cleland J. Population growth in the 21st century: cause for crisis or celebration? Trop Med Int Health. 1996;1:15–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1996.d01-8.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leon DA, Chenet L, Shkolnikov VM, Zakharov S, Shapiro J, Rakhmanova G, et al. Huge variation in Russian mortality rates 1984-94: artefact, alcohol, or what? Lancet. 1997;350:383–388. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)03360-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boseley S. Deadly serious. Interview with Clare Short, secretary of state at the Department for International Development. Guardian 1999 June 30.