Abstract

Rhesus macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) containing either a large nef deletion (SIVmac239Δ152nef) or interleukin-2 in place of nef developed high virus loads and progressed to simian AIDS. Viruses recovered from both juvenile and neonatal macaques with disease produced a novel truncated Nef protein, tNef. Viruses recovered from juvenile macaques infected with serially passaged virus expressing tNef exhibited a pathogenic phenotype. These findings demonstrated strong selective pressure to restore expression of a truncated Nef protein, and this reversion was linked to increased pathogenic potential in live attenuated SIV vaccines.

Infection of macaques with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) provides opportunities to test the in vivo significance and function of viral genes and regulatory elements and to evaluate viral vectors (7). Importantly, this highly manipulatable animal model for human immunodeficiency virus infection and AIDS also enables exploration of antiviral immunization approaches, including live attenuated viral vaccines. Several pathogenesis and vaccine studies have been performed with derivatives of the molecular clone SIVmac239, which is pathogenic in adult rhesus macaques. The viral accessory gene nef encodes a multifunctional protein that modulates cell activation pathways, down-regulates the CD4 receptor for the virus and major histocompatibility complex class I molecules, and enhances virion infectivity (22). Although Nef is dispensable for viral replication in cell cultures in vitro (25), Nef is important for the induction of high virus loads and progression to fatal simian AIDS (SAIDS) (12). Adult macaques infected with a clone containing a large deletion in nef (SIVmac239Δnef) exhibited low virus loads and did not display clinical signs of disease for an observation period of 2 years. These findings indicated that nef was important for both high viremia and pathogenesis in juvenile and adult macaques and provided the basis for designing live attenuated SIV vaccines, which are based on viral clones with deletions in accessory genes (1, 4) rather than on viral clones with premature stop codons in accessory genes (20). However, more recent studies have demonstrated that a derivative of SIVmac239, also with a large deletion in nef, produced a fatal AIDS-like disease both in newborn macaques (2, 30) and, with low efficiency, in adult macaques (3). Although this latter observation raised concern about the safety of live attenuated primate lentivirus vaccines, the potential for viral genetic changes was not explored in animals displaying disease after infection with viral clones containing deletions in nef. Previous studies showed that primate immunodeficiency viruses containing large deletions in the nef gene (4) or substitutions of cytokine genes in place of nef (8, 10) were attenuated for virulence in juvenile and adult macaques. Thus, such viruses could serve as live attenuated vaccines to prevent viral infection and AIDS.

Infection of macaques with SIVmac239Δ152nef and SIV IL-2 vectors.

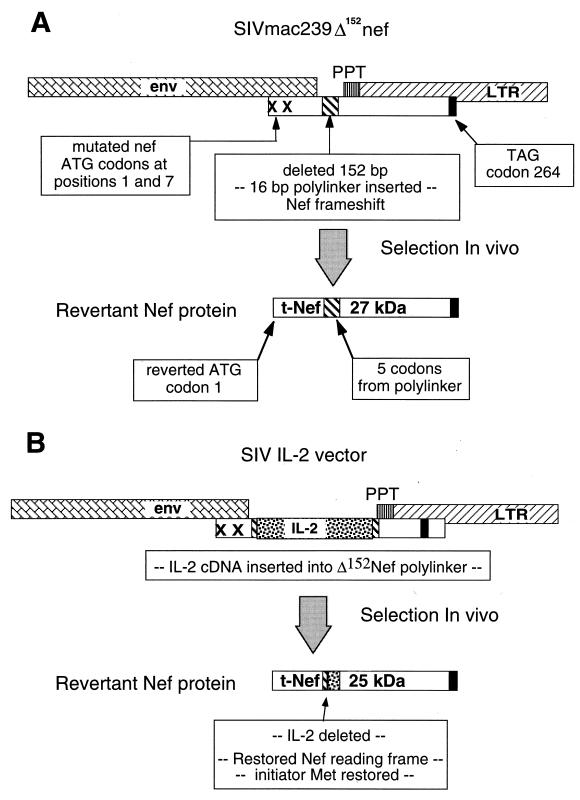

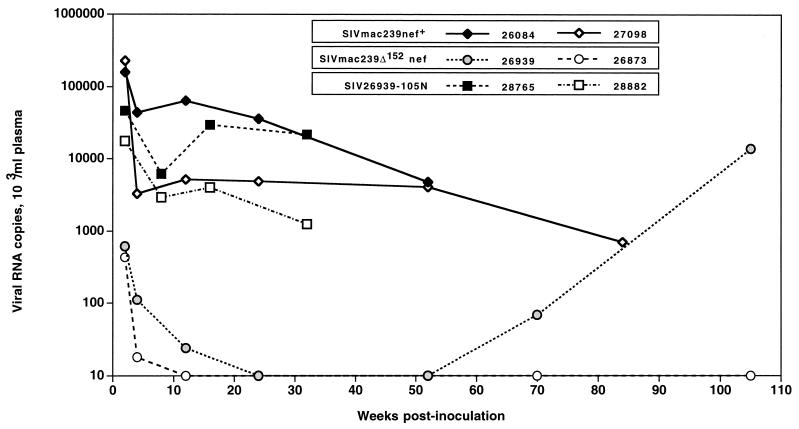

We report on the results of a long-term study, done with juvenile and newborn macaques, aimed at testing a clone of SIV with a large 152-bp deletion in the unique region of nef that does not overlap the viral env or 3′ long terminal repeat (LTR) (SIVmac239Δ152nef) (Fig. 1A). The SIVΔnef clone was generated in the plasmid pMA239 (24), containing the proviral form of SIVmac239 (GenBank accession no. M33262), which was modified as follows: (i) nef sequences between the end of env and the polypurine tract at the 5′ end of the 3′ LTR were replaced with a polylinker that shifts the Nef sequence out of frame, and (ii) to preclude translational initiation, the two methionine (ATG) codons at the start of nef were mutated to threonine codons (ACG) (Fig. 1A). The mutated SIV clone was verified by DNA sequence analysis. An expectation was that this nef deletion virus would establish a low-level infection without disease in juvenile macaques (4, 29). Two juvenile macaques (Mmu 26939 and Mmu 26873) were inoculated intravenously with 1,000 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50) of SIVmac239Δ152nef. Cell-free virus stocks were prepared and titers were determined as described previously (13, 23). Viral loads in plasma (branched chain DNA for viral RNA; Chiron) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (cell-associated virus load) were determined as previously described (13, 23). Plasma viral loads reached a peak at 2 weeks after infection and declined to low levels thereafter (Fig. 2). The plasma viral loads in these two macaques, during this acute phase, were lower by more than 100-fold compared to viral loads in macaques infected with SIVmac239nef+ (Fig. 2). Mmu 26873 contained low amounts of virus and remained healthy with no disease signs during the 2-year observation period. In striking contrast, Mmu 26939 exhibited an increase in virus load at about 70 weeks. At the time of necropsy (105 weeks), levels of virus in this animal were similar to levels measured in macaques infected with the pathogenic clone SIVmac239nef+ (Fig. 2). Additionally, the CD4+ T-cell numbers and CD4/CD8 T-cell ratio of Mmu 26939 declined during the latter stage of infection (data not shown). Salient pathologic findings are presented in Table 1. Virus recovered from this animal at necropsy was designated SIV-26939-105N.

FIG. 1.

Diagram of the SIVmac239Δnef and SIV cytokine vectors expressing human and rhesus IL-2. (A) For SIVmac239Δ152nef, the initiator methionine (ATG) codon and the methionine codon at amino acid position 7 of SIVmac239 Nef were mutated to threonine codons (ACG). Additionally, a 152-bp region of Nef was deleted from the unique region that does not overlap the env gene, polypurine tract (PPT), and 3′ LTR. To facilitate the insertion of the cytokine genes, a 16-bp linker was inserted in the deleted region. The generation of tNef in vivo is indicated. (B) For the viral vectors expressing human and rhesus IL-2, the respective genes were inserted into the linker region of SIVmac239Δ152nef. The generation tNef from the SIV IL-2 vectors in vivo is indicated.

FIG. 2.

Viral load in juvenile macaques infected with SIVmac239Δ152nef, SIVmac239nef+, and SIV-26939-105N. Plasma samples were collected at several time points during the course of infection. Viral loads for infected macaques were measured by branched-DNA assay. Juvenile macaques were inoculated with SIVmac239Δ152nef (Mmu 26939 and Mmu 26873), SIVmac239nef+ (Mmu 26084 and Mmu 27098), or SIV-26939-105N (Mmu 26939 [virus recovered at necropsy], Mmu 28765, and Mmu 28882).

TABLE 1.

Clinical and pathologic findings in infected macaques

| Virus | Animal | Age at inoculation | Clinical signs and premortem laboratory data | Postmortem findings | Viral load | Nefa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIVmac239Δ152nef | Mmu 26873 | 31 mo | Normal CD4 T-cell levels; normal weight gain | Necropsy at 105 wk; no abnormalities in lymphoid or other organs | Low | ND |

| Mmu 26939 | 30 mo | Normal range for CD4 T cells; reduced CD4/CD8 cell ratio at 72–105 wks; normal weight gain | Necropsy at 105 wk; lymphoid hyperplasia; multiorgan infiltration with inflammatory cells; splenomegaly; interstitial pneumonia and bronchitis | High | tNef | |

| SIVmac239nef+ | Mmu 26084 | 39 mo | Weight loss, diarrhea; lymphadenopathy; thrombocytopenia; splenomegaly; pneumonia | Necropsy at 51 wk PIb; lymphoid depletion, thymic atrophy; Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia; encephalitis | High | Nef |

| Mmu 27098 | 26 mo | Weight loss, diarrhea; lymphadenopathy; persistent bacterial rhinitis | Necropsy at 87 wk PI; lymphoid hyperplasia to depletion; gastrointestinal giardiasis and cryptosporidiosis | High | Nef | |

| SIV-26939-105N | Mmu 28765 | 31 mo | CD4 T-cell levels normal; diarrhea, weight loss | Alive at 95 wk | High | tNef |

| Mmu 28882 | 30 mo | CD4 T-cell decline below 200; CD4/CD8 ratio inverted; diarrhea | Necropsy at 79 wk PI; marked lymphoid hyperplasia; perotinitis, serositis, pancreatitis; Cryptosporidium, Campylobacter spp. | High | tNef | |

| SIVmac239-huIL2 | Mmu 27021 | 38 mo | CD4 T-cell decline; hemolytic anemia; weight loss | Necropsy at 46 wk PI; hemolytic anemia; lymphoid depletion in spleen and multiple lymph nodes | Moderate | tNef |

| Mmu 27008 | 30 mo | Normal CD4 T-cell levels; normal weight gain | Alive at 105 wk PI, healthy | Low | ND | |

| SIVmac239-mmIL2 | Mmu 29450 | 2 days | CD4 T-cell decline; weight loss | Necropsy at 80 wk PI; lymphoid depletion in spleen and multiple lymph nodes; thymic atrophy; severe gastritis, stomach adenocarcinoma; encephalitis; oral candidiasis, Mycobacterium avium | High | tNef |

| Mmu 29460 | 2 days | Normal CD4 T-cell levels; normal weight gain | Alive at 105 wk PI, healthy | Low | ND | |

| SIVmac239-mmIL2 | Mmu 29810 | 2 days | Rapid CD4 T-cell depletion; intermittent diarrhea; weight loss | Necropsy at 24 wk PI; multifocal thrombosis (acute myocardial infarction); widespread lymphoid depletion (lymph nodes and spleen); thymic atrophy, gastroenteropathy; oral candidiasis, Cryptosporidium | High | tNef |

| Mmu 29811 | 2 days | CD4 T-cell decline | Necropsy at 96 wk PI; paracortical expansion in lymph nodes; lymphoid depletion in spleen and thymus; severe pneumonia, P. carinii | Moderate | ND |

Nef and tNef expression was detected by immunoblot analysis with the polyclonal anti-SIV Nef serum. ND, not detected.

PI, postinoculation.

To provide a comparison for the results of infection with all of the viruses in this report, clinical and virus load data are shown for two juvenile macaques (Mmu 26084 and Mmu 27098) infected with a cell-free preparation of SIVmac239nef+ at 1,000 TCID50 per animal (13, 23). Viral loads in Mmu 26084 and Mmu 27098 reached a peak at 2 weeks after infection and were maintained at high levels (Fig. 2), and both animals progressed to SAIDS (Table 1) (13, 23).

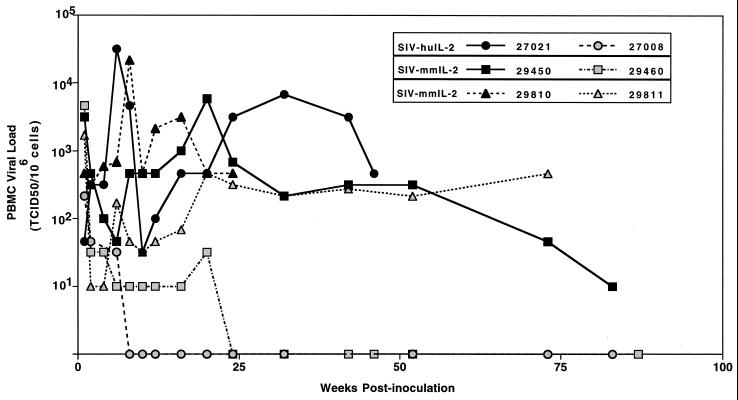

This report also describes the outcome of infection of rhesus macaques infected with cytokine vectors built from the nef deletion virus (Fig. 1B). The cDNA for human and rhesus interleukin-2 (IL-2) was inserted into the polylinker of SIVΔ152Nef (Fig. 1B). An expectation was that these replication-competent viral vectors, designated SIV-huIL2 and SIV-mmIL2, would also establish a low-level persistent infection without disease (10). Two juvenile macaques inoculated with 1,000 TCID50 of SIV-huIL2 showed low virus loads in the first 4 weeks of infection (Fig. 3). In one animal, Mmu 27008, virus remained at very low levels for over 2 years; no hematological abnormalities or other clinical signs of immunodeficiency disease were observed. In contrast, Mmu 27021 showed high virus load at 6 to 8 weeks postinfection; this was followed by a decline and then an increase in virus load at 16 to 20 weeks (Fig. 3). Thereafter, this animal contained large amounts of virus, lost about 15% of body weight, and progressed to an AIDS-like disease (Table 1). At 17 weeks postinoculation, Mmu 27021 was diagnosed with a hemolytic anemia (C. Mandell, personal communication). Analysis at necropsy revealed lymphoid depletion in spleen and multiple lymph nodes (Table 1).

FIG. 3.

Viral load in macaques infected with the SIV IL-2 vectors. PBMC samples were collected at various time points after infection, and viral load in juvenile macaques (Mmu 27008 and Mmu 27021) infected with SIV-huIL2 and newborn macaques (Mmu 29450, Mmu 29460, Mmu 29810, and Mmu 29811) infected with SIV-mmIL2 was measured.

To explore the pathogenic potential of the viral vector in newborn rhesus macaques, four newborn animals were inoculated with 500 TCID50 of SIV-mmIL2. All four exhibited moderate virus loads in the first 2 weeks of infection (Fig. 3). In Mmu 29460 and Mmu 29811, virus load declined and remained at low levels for over 2 years. Both of these animals were healthy for this 2-year period, with normal hematological parameters, and displayed normal patterns of growth. In contrast, both Mmu 29450 and Mmu 29810 maintained moderate levels of virus throughout the course of infection (Fig. 3). Mmu 29810 exhibited CD4+-T-cell depletion in peripheral blood, intermittent diarrhea, and severe weight loss. Mmu 29450 also showed a decline in CD4+ T cells and weight loss during the course of infection (data not shown). Necropsy analysis of both animals revealed severe lymphoid abnormalities and the presence of opportunistic infections (Table 1). Recently, Mmu 29811 also developed signs of SAIDS and was euthanatized at 96 weeks after infection. Salient features at necropsy, characteristic of SAIDS, are briefly described in Table 1.

Analysis of Nef protein in viruses recovered from infected macaques.

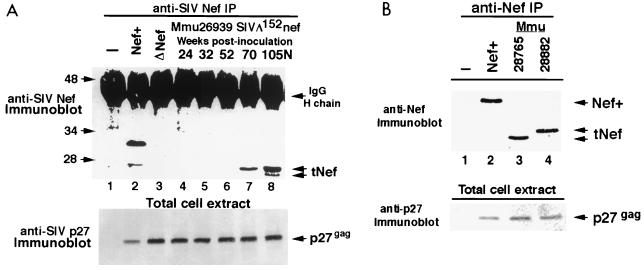

Previous studies demonstrated that the conversion of SIV clones, containing Nef mutations, to a pathogenic phenotype in vivo was linked to reversion of the introduced mutations (12, 13, 28). Accordingly, to determine whether changes (i.e., reversions) had occurred in the mutated nef gene of SIVmac239Δ152nef or the SIV IL-2 vectors to restore Nef expression in vivo, immunoblot analysis was performed on Nef immunoprecipitates from extracts of CEMx174 cells that were infected with virus recovered from macaques exhibiting high virus load as described previously (23). Attention was first directed at SIV-26939-105N, the virus recovered from the SIVmac239Δ152nef-infected animal Mmu 26939. Surprisingly, immunoblot analysis of immunoprecipitates with antibodies to Nef revealed that SIV-26939-105N expressed novel truncated Nef (tNef) proteins of approximately 25 and 27 kDa (Fig. 4A). Nef encoded by the prototype virus SIVmac239nef+ was 32 kDa (Fig. 4A). Importantly, neither of these 25- and 27-kDa tNef proteins was observed in similar immunoblot analysis of cells infected with a stock of SIVmac239Δ152nef (Fig. 4A, lane 3) or in virus isolated at 105 weeks postinfection from the second animal in this group, Mmu 26873, which remained healthy and contained a very low virus load (data not shown). A time course analysis revealed that viruses recovered from Mmu 26939 at 24, 32, or 52 weeks postinoculation did not express proteins detectable with the anti-SIV Nef antibody (Fig. 4A, lanes 4 to 6). However, a 27-kDa form of tNef was observed in virus from Mmu 26939 at the 70-week time point (Fig. 4A, lane 7), indicating that mutational changes had occurred in the nef gene (Fig. 1A) between weeks 52 and 70 to allow expression of tNef. The restoration of Nef expression in virus recovered from Mmu 26939 at 70 weeks postinfection corresponded to the increase in plasma viral loads (Fig. 2). The size range of the tNef proteins was consistent with the size predicted if the amino- and carboxy-terminal portions of the mutated nef gene from SIVmac239Δ152nef were joined into one translation frame and initiated at the authentic nef start codon (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 4.

Expression of tNef in Mmu 26939 with high viral load after infection with SIVmac239Δ152nef. (A) Immunoblot analysis was performed on anti-SIV Nef immunoprecipitates from cell extracts of uninfected CEMx174 cells (lane 1) or CEMx174 cells infected with SIVmac239nef+ (lane 2), SIVmac239Δ152nef (lane 3), or virus recovered from Mmu 26939 (infected with SIVmac239Δ152nef) at 24, 32, 52, 70, and 105 weeks postinoculation (PI) (lanes 4 to 8). Mmu 26939 was necropsied at 105 weeks postinoculation; virus recovered at necropsy was designated SIV-26939-105N. Arrows on the right indicate the position of immunoglobulin G heavy chain (IgG H chain) and tNef proteins. Molecular mass markers are given on the left, in kilodaltons. The bottom portion shows an immunoblot of total cell extracts that was probed with antibody to SIV p27gag to monitor the level of replicating virus; the lane designations are the same as in the anti-SIV Nef blot described above. (B) Analysis of Nef expression in macaques infected with SIV-26939-105N. Anti-SIV Nef immunoprecipitates of uninfected CEMx174 cells (lane 1) and SIVmac239nef+ (lane 2) were used as controls. Viruses from Mmu 28765 and Mmu 28882 (infected with SIV-26939-105N) are shown in lanes 3 and 4, respectively. Molecular mass markers are given on the left, in kilodaltons. Note that the 27- and 25-kDa bands representing tNef have segregated in the two monkeys (see arrows). Immunoblot analysis was also performed with anti-SIV p27gag on total cell extracts from CEMx174 cells infected with these viruses to monitor the level of replicating virus in each sample (bottom).

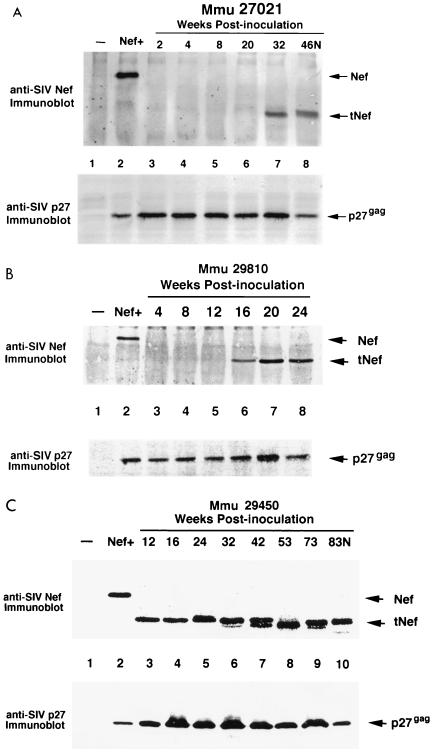

In several macaques inoculated with SIV IL-2 vectors that displayed high virus loads (Fig. 3), truncated forms of Nef were also detected in viruses recovered at various intervals after infection. For Mmu 27021, Mmu 29810, and Mmu 29450, tNef was observed after 12, 16, and 32 weeks postinoculation, respectively (Fig. 5). The size of tNef was 25 kDa for all the viruses recovered at the time of necropsy in these three animals (Fig. 5). However, in the case of virus from Mmu 29450, the size of tNef decreased from 27 kDa (at 12 weeks postinoculation) to 25 kDa (at the time of necropsy) (Fig. 5C). One macaque (Mmu 29811) that was inoculated with SIV-mmIL2 exhibited moderate virus loads throughout the course of infection and eventually developed SAIDS. Virus recovered from Mmu 29811 at necropsy or earlier did not produce protein detectable with the polyclonal anti-SIV Nef serum (data not shown). Immunoblot analysis of viruses isolated from macaques which exhibited low virus loads, Mmu 26873, Mmu 27008, and Mmu 29460, did not express any Nef proteins at necropsy (105 days for Mmu 26873) or at any intermediate time points (data not shown). Thus, the results from the immunoblot analysis of viruses recovered from macaques displaying immunodeficiency symptoms after infection with SIVmac239Δ152nef or the SIV IL-2 vectors revealed a close link between expression of tNef in vivo and progression to disease.

FIG. 5.

Expression of tNef in macaques with high virus load after infection with SIV IL-2 vectors. Viruses recovered from infected animals were inoculated into cultures of CEMx174 cells, and total cell extracts were prepared. The top part of each panel shows the results of an immunoblot analysis performed with antibody to SIV Nef. To measure the level of replicating virus in each sample, immunoblots were probed with antibody to SIV p27gag. The lane designations for the anti-SIV Nef and SIV p27gag are the same for each pair of panels. Anti-SIV Nef immunoprecipitates of uninfected CEMx174 cells (lanes 1) and SIVmac239Nef+ (lanes 2) were used as controls. (A) Virus recovered from Mmu 27021 (infected with SIV-huIL2) at 2, 4, 8, 20, 32, and 46 weeks postinoculation (PI) (lanes 4 to 8). (B) Virus recovered from Mmu 29810 (infected with SIV-mmIL2) at 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 weeks postinoculation (lanes 3 to 8). (C) Virus recovered from Mmu 29450 (infected with SIV-mmIL2) at 12, 16, 24, 32, 42, 53, 73, and 83 weeks postinoculation (lanes 3 to 10). Mmu 29450 was necropsied at 83 weeks postinoculation (83N).

Inoculation of macaques with viruses expressing tNef.

To test the pathogenic potential of the virus expressing tNef, SIV-26939-105N, two juvenile macaques (Mmu 28765 and Mmu 28882) were inoculated intravenously with 1,000 TCID50 of cell-free virus. Measurement of cell-associated and plasma viral loads revealed high levels of virus in the acute (2 to 4 weeks postinoculation) and chronic stages (8 weeks postinoculation and onward) of virus infection (Fig. 2). At the 2-week time point, virus levels were about 10-fold lower, comparable to levels measured in macaques infected with SIVmac239nef+; thereafter, virus levels in SIV-26939-105N-infected animals were in the same range as levels in SIVmac239nef+-infected animals (Fig. 2). CD4+-T-cell numbers in Mmu 28765 remains relatively normal 40 weeks after infection, whereas, for Mmu 28882, this T-cell subset declined dramatically to below 200 cells/μl of blood at 32 weeks (data not shown). The decline in CD4+ T cells for Mmu 28882 reflected progression to SAIDS. Virus was recovered from the two SIV-26939-105N-infected animals, Mmu 28765 and Mmu 28882 at several time points after infection and analyzed for expression of tNef by immunoblot analysis.

Interestingly, unlike the SIV-26939-105N inoculum, which produced two forms of tNef, 27 and 25 kDa (Fig. 4A), virus from each of these recipient animals exhibited a single tNef protein, 27 kDa for virus from Mmu 28765 and 25 kDa for virus from Mmu 28882 (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that the 27- and 25-kDa forms of tNef from the SIV-26939-105N inoculum segregated in separate macaques. Because both Mmu 28882 and Mmu 28765 maintained high viral loads (Fig. 2), the size of tNef (27 versus 25 kDa) does not appear to influence levels of viral replication in vivo. Mmu 28882 died of SAIDS 79 weeks postinoculation. Mmu 28765 is alive but is experiencing diarrhea and weight loss. This monkey continues to be monitored for viral load and clinical signs of immunodeficiency disease.

Sequence analysis of virus recovered from infected macaques.

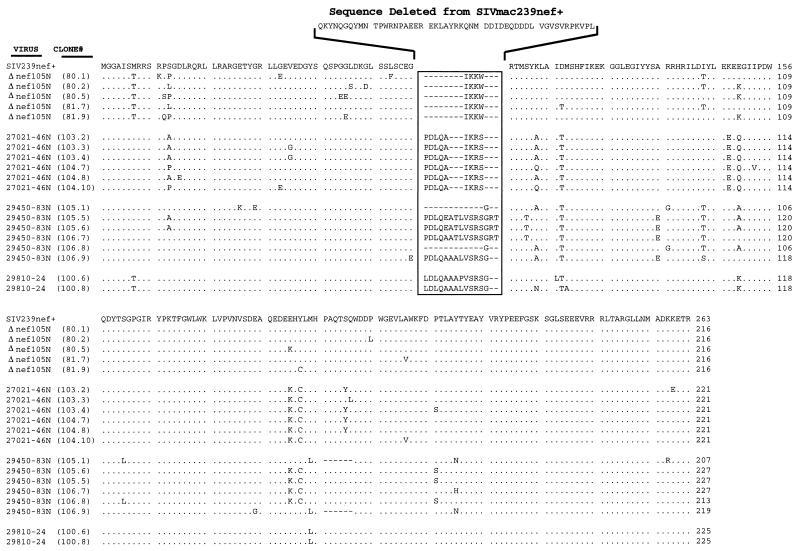

As shown above, viruses recovered from several macaques exhibiting disease after infection with SIVmac239Δ152nef or SIV IL-2 vectors produced various forms of Nef protein that were smaller than that detected in cells infected with SIVmac239nef+. To directly determine the nucleotide changes underlying reversion events in these viruses recovered at necropsy, the region of the viral genome containing nef was amplified by PCR and sequenced. DNA was isolated from either 400 μl of whole blood, 107 PBMC obtained from infected animals, or 107 acutely infected CEMx174 cells cocultivated with purified PBMC, and PCR was performed as described previously (13). Sequence analysis of the nef region of SIV-26939-105N (juvenile Mmu 26939 infected with SIVmac239Δ152nef) showed restoration of the ATG encoding Met at position 1 of Nef; however, the mutant codon at position 7 was not reverted (Fig. 1A and 6). Additionally, the region containing the 16-bp oligonucleotide that replaced 152 bp of nef was altered; several bases were changed and 1 bp was deleted (Fig. 1A and 6). These changes restored the N-terminal Nef open reading frame, which contains amino acids 1 to 57, encoded 4 amino acids from the mutated oligonucleotide insert and restored the C-terminal open reading frame, encoding amino acids 109 to 263 (Fig. 1A and 6). Each of the five nef clones for SIV-26939-105N also contained about six amino acid substitutions throughout Nef (Fig. 6). These substitutions were not uniformly conserved in all PCR clones. The predicted Nef protein, containing 217 amino acids, is estimated to have a molecular mass of 25 kDa; this size estimate matches closely the Nef protein detected by immunoblotting after electrophoresis in polyacrylamide gels under denaturing conditions (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 6.

DNA sequence analysis of viruses expressing tNef. Sequence alignments for truncated Nef proteins recovered at necropsy from monkeys infected with SIVmac239Δ152nef, SIV-huIL2, or SIV-mmIL2. All of the tNef sequences were compared and aligned with the amino acid sequence for SIVmac239nef+ (top sequence). Viruses recovered from Mmu 26939 (infected with SIVmac239Δ152nef), Mmu 27021 (infected with SIV-huIL2), Mmu 29450 (infected with SIV-mmIL2), and Mmu 29810 (infected with SIV-mmIL2) were designated SIV-26939-105N, SIV-27021-46N, SIV-29450-83N, and SIV-29810-24, respectively. Individual PCR clones are shown in parentheses. Dots indicate positions of sequence identity with SIVmac239nef+, dashes indicate insertion of gaps, and amino acid substitutions are shown as single-letter abbreviations. Numbers indicate amino acid position. Amino acids deleted from SIVmac239nef+ are shown above the nef deletion region.

Similarly, DNA sequence analysis performed on three viruses, designated SIV-27021-46N (juvenile Mmu 27021), SIV-29450-83N (neonate Mmu 29450), and SIV-29810-24 (neonate 29810), that were recovered at or near necropsy from macaques infected with the SIV IL-2 vectors revealed that the first ATG codon was restored for the nef translation frames of all three viruses (Fig. 1B and 6). SIV-27021-46N and SIV-29450-83N also showed reversion of the ATG codon at position 7 in Nef, whereas SIV-29810-24 retained the mutant codon at this position (Fig. 6). All three viruses deleted the majority of IL-2 sequences such that the two portions of Nef, positions 1 to 57 and 109 to 263, were joined into a single translation frame. About six amino acid substitutions were noted in each nef deletion clone (Fig. 1B and 6). Based on the DNA sequence analysis, the Nef proteins for SIV-27021-46N, SIV-29450-83N, and SIV-29810-24 are predicted to have a molecular mass of 25 to 27 kDa; this is in good agreement with the size of Nef measured by electrophoresis in polyacrylamide gels (Fig. 5).

Implications of tNef.

The finding that several macaques infected with either SIVmac239Δ152nef or the SIV IL-2 vectors exhibited high virus load, immunodeficiency disease, and produced virus that expressed tNef demonstrated strong selection for this novel form of Nef in vivo (Table 1). Additionally, tNef expression was maintained in virus recovered from the two animals infected with SIV-26939-105N, Mmu 28765 and Mmu 28882 (Table 1). Regions of Nef that are retained in tNef include the N-terminal myristylation (membrane targeting) site (27), the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (YxxL) that are critical for cell activation and interaction with Src homology region 2 domains (6, 17), the region(s) necessary for binding to several cellular proteins (i.e., ATPase catalytic subunit, or Nef binding protein 1) (16), the adaptin molecule in clathrin-containing endosomes (15, 21), thioesterase (26), and Raf kinase (11), as well as the motifs that are important for Nef-mediated down-modulation of CD4 and major histocompatibility complex class I antigen and Nef internalization (reviewed in references 9 and 22). Because these regions of Nef were retained during in vivo selection for tNef, it is likely that one or more of these functions were necessary for induction of high viral load and progression to disease. Nef sequences deleted in tNef include regions necessary for binding to the CD4 antigen, the cleavage site for viral protease, sequences required for enhancement of virion infectivity, and the SH3-ligand domain (PxxP motif), which interacts with the Hck tyrosine kinase and the signaling adapter Nck (18, 22). The SH3-ligand domain is also necessary for activation of the Nef-associated kinase (NAK) (13). Analysis of tNef in the NAK assay revealed that this form of Nef was not capable of activating NAK. Thus, this finding indicates that high virus load and progression to SAIDS can occur in the absence of NAK activation.

The time at which virus produced tNef was examined by immunoblot analysis of viruses recovered from infected animals at different intervals after inoculation. Interestingly, tNef was detected at earlier time points after inoculation with the SIV IL-2 vectors than SIVmac239Δ152nef. Viral load during the acute stage of infection was greater for the animals infected with the SIV IL-2 vectors than for animals infected with SIVmac239Δ152nef. Thus, it is possible that expression of IL-2 in the early stage of infection may have enhanced viral replication of the vector virus and thereby accelerated both the deletion of IL-2 sequences and the restoration of the open reading frame for tNef. A related issue concerns the order of genetic changes in the genomes of SIVmac239Δ152nef and the SIV IL-2 vectors that produced the translation frame for tNef. Additional experiments, examining viral sequences during the course of infection, are required to determine the precise relationship of the reversion event that restored the tNef initiation codon to the changes that joined the N-terminal portion to the C-terminal portion of tNef (Fig. 1 and 6). This study represents the first report linking a truncated form of Nef with immunodeficiency disease.

A previous study found that a large deletion of SIV nef (SIVmac239Δnef) was sufficient for attenuating this virus in juvenile and adult macaques (12). Moreover, inoculation with viruses containing large deletions of Nef protected macaques from challenge with pathogenic virus (4). The best protection was achieved if the challenge virus was administered at least 1 year after inoculation with the live attenuated vaccine virus (4, 30). Although the nef deletion virus (i.e., SIVmac239Δ152nef) used in our report was different from nef-deleted SIV clones in previous studies, the SIVmac239Δ152Nef virus was capable of causing disease 2 years after inoculation without exposure to a pathogenic challenge virus. These results imply that, although the immune system had sufficient time to mount a response to control the input virus (i.e., SIVmac239Δ152nef), an alteration in the viral genome may have occurred to enable the virus to escape host immune responses. Whether escape of virus from the immune system was dependent on expression of tNef, and/or some other (compensating) mutation that occurred elsewhere in the viral genome, remains to be determined. Importantly, the findings in our report have implications for human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals who harbor virus containing large deletions in nef and show low virus loads without apparent disease (5, 14, 19). Accordingly, further characterization of pathogenic viruses expressing tNef will provide insight into molecular changes in the viral genome that are necessary for pathogenic conversion of both live attenuated viral vaccines and viral variants that contain deletions in nef and appear to be avirulent.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the expert technical assistance of Tesi Low, Kim Schmidt, Jo Weber, Michael Stout, and Erwin Antonio. Murray Gardner, Carol Mandell, Ross Tarara, and Don Canfield provided expertise in performing necropsies and histopathologic analysis. We also thank C. Mandell for providing an analysis of the hematologic data. We thank Francois Villinger (Emory University, Atlanta, Ga.) for providing the cDNA clones for rhesus and human IL-2.

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants to E.T.S. (R29-AI38718), and P.A.L. (RO1-AI38523), the Base Grant to the California Regional Primate Research Center (RR-00169), and grants from the University-wide AIDS Research Program (UARP; K98-D141), UC Davis School of Medicine (Hibbard Williams Award), and UCSF AIDS Clinical Research Center (Pilot Project) to E.T.S.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

Mmu 28765 was necropsied at 103 weeks postinoculation. It exhibited diarrhea and wasting. Histopathologic analysis of the tissues from this animal is in progress. Another macaque was infected with SIVmac239-huIL2, Mmu 29052. This animal died of SAIDS at 20 weeks postinoculation. Truncated Nef was not detected by immunoblot analysis; however, DNA sequence analysis revealed a restored Nef open reading frame that was smaller than that of tNef. This additionally truncated form of Nef lacks the N terminus as well as a C-terminal region important for endosomal sorting (V. Piguet, F. Gu, M. Foti, N. Demaurex, J. Gruenberg, J. L. Carpentier, and D. Trono, Cell 97:63–73, 1999).

REFERENCES

- 1.Almond N, Rose J, Sangster R, Silvera P, Stebbings R, Walker B, Stott E J. Mechanisms of protection induced by attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus. I. Protection cannot be transferred with immune serum. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:1919–1922. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-8-1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba T W, Jeong Y S, Pennick D, Bronson R, Greene M F, Ruprecht R M. Pathogenicity of live, attenuated SIV after mucosal infection of neonatal macaques. Science. 1995;267:1820–1825. doi: 10.1126/science.7892606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baba T W, Liska V, Khimani A H, Ray N B, Dailey P J, Pennick D, Bronson R, Greene M F, McClure H M, Martin L N, Ruprecht R M. Live attenuated, multiply deleted simian immunodeficiency virus causes AIDS in infant and adult macaques. Nat Med. 1999;5:194–203. doi: 10.1038/5557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daniel M D, Kirchhoff F, Czajak S C, Sehgal P K, Desrosiers R C. Protective effects of a live attenuated SIV vaccine with a deletion in the nef gene. Science. 1992;258:1938–1941. doi: 10.1126/science.1470917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deacon N J, Tsykin A, Solomon A, Smith K, Ludford-Menting M, Hooker D J, McPhee D A, Greenway A L, Ellett A, Chatfield C, Lawson V A, Crowe S, Maerz A, Sonza S, Learmont J, Sullivan J S, Cunningham A, Dwyer D, Dowton D, Mills J. Genomic structure of an attenuated quasi species of HIV-1 from a blood transfusion donor and recipients. Science. 1995;270:988–991. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du Z, Lang S M, Sasseville V G, Lackner A A, Ilynskii P O, Daniel M D, Jung J U, Desrosiers R C. Identification of a nef allele that causes lymphocyte activation and acute disease in macaque monkeys. Cell. 1995;82:665–674. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner M B, Luciw P A. Simian retroviruses. In: Wormser G, editor. AIDS and other manifestations of HIV infection. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giavedoni L, Ahmad S, Jones L, Yilma T. Expression of gamma interferon by simian immunodeficiency virus increases attenuation and reduces postchallenge virus load in vaccinated rhesus macaques. J Virol. 1997;71:866–872. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.866-872.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenberg M E, Iafrate A J, Skowronski J. The SH3 domain-binding surface and an acidic motif in HIV-1 Nef regulate trafficking of class I MHC complexes. EMBO J. 1998;17:2777–2789. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.10.2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gundlach B R, Linhart H, Dittmer U, Sopper S, Reiprich S, Fuchs D, Fleckenstein B, Hunsmann G, Stahl-Hennig C, Uberla K. Construction, replication, and immunogenic properties of a simian immunodeficiency virus expressing interleukin-2. J Virol. 1997;71:2225–2232. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2225-2232.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hodge D R, Dunn K J, Pei G K, Chakrabarty M K, Heidecker G, Lautenberger J A, Samuel K P. Binding of c-Raf1 kinase to a conserved acidic sequence within the carboxyl-terminal region of the HIV-1 Nef protein. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15727–15733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kestler H W, Ringler D J, Mori K, Panicali D L, Sehgal P K, Daniel M D, Desrosiers R C. Importance of the nef gene for maintenance of high virus loads and for the development of AIDS. Cell. 1991;65:651–662. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90097-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan I H, Sawai E T, Antonio E, Weber C J, Mandell C P, Montbriand P, Luciw P A. Role of the SH3-ligand domain of simian immunodeficiency virus Nef in interaction with Nef-associated kinase and simian AIDS in rhesus macaques. J Virol. 1998;72:5820–5830. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5820-5830.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirchhoff F, Greenough T C, Brettler D B, Sullivan J L, Desrosiers R C. Brief report: absence of intact nef sequences in a long-term survivor with nonprogressive HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:228–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501263320405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Gall S, Erdtmann L, Benichou S, Berlioz-Torrent C, Liu L, Benarous R, Heard J M, Schwartz O. Nef interacts with the mu subunit of clathrin adaptor complexes and reveals a cryptic sorting signal in MHC I molecules. Immunity. 1998;8:483–495. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80553-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu X, Yu H, Liu S H, Brodsky F M, Peterlin B M. Interactions between HIV1 Nef and vacuolar ATPase facilitate the internalization of CD4. Immunity. 1998;8:647–656. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80569-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo W, Peterlin B M. Activation of the T-cell receptor signaling pathway by Nef from an aggressive strain of simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1997;71:9531–9537. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9531-9537.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manninen A, Hipakka M, Vihinen M, Lu W, Mayer B J, Saksela K. SH3-domain binding of HIV-1 Nef is required for association with a PAK-related kinase. Virology. 1998;250:273–282. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mariani R, Kirchhoff F, Greenough T C, Sullivan J L, Desrosiers R C, Skowronski J. High frequency of defective nef alleles in a long-term survivor with nonprogressive human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1996;70:7752–7764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7752-7764.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marthas M L, Ramos R A, Lohman B L, Van Rompay K, Unger R E, Miller C J, Banapour B, Pedersen N C, Luciw P A. Viral determinants of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) virulence in rhesus macaques assessed by using attenuated and pathogenic molecular clones of SIVmac. J Virol. 1993;67:6047–6055. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6047-6055.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piguet V, Chen Y L, Mangasarian A, Foti M, Carpentier J L, Trono D. Mechanism of Nef-induced CD4 endocytosis: Nef connects CD4 with the mu chain of adaptor complexes. EMBO J. 1998;17:2472–2481. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.9.2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saksela K. HIV-1 Nef and host cell protein kinases. Frontiers Biol. 1997;2:606–618. doi: 10.2741/a217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sawai E T, Khan I H, Montbriand P M, Peterlin B M, Cheng-Mayer C, Luciw P A. Activation of PAK by HIV and SIV Nef: importance for AIDS in rhesus macaques. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1519–1527. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(96)00757-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shibata R, Adachi A. SIV/HIV recombinants and their use in studying biological properties. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1992;8:403–409. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trono D. HIV accessory proteins: leading roles for the supporting cast. Cell. 1995;82:189–192. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90306-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watanabe H, Shiratori T, Shoji H, Miyatake S, Okazaki Y, Ikuta K, Sato T, Saito T. A novel acyl-CoA thioesterase enhances its enzymatic activity by direct binding with HIV Nef. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;238:234–239. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welker R, Kottler H, Kalbitzer H R, Krausslich H-G. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef protein is incorporated into virus particles and specifically cleaved by the viral proteinase. Virology. 1996;219:228–236. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whatmore A M, Cook N, Hall G A, Sharpe S, Rud E W, Cranage M P. Repair and evolution of nef in vivo modulates simian immunodeficiency virus virulence. J Virol. 1995;69:5117–5123. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.5117-5123.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wyand M S, Manson K H, Garcia-Moll M, Montefiori D, Desrosiers R C. Vaccine protection by a triple deletion mutant of simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1996;70:3724–3733. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3724-3733.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wyand M S, Manson K H, Lackner A A, Desrosiers R C. Resistance of neonatal monkeys to live attenuated vaccine strains of simian immunodeficiency virus. Nat Med. 1997;3:32–36. doi: 10.1038/nm0197-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]