Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study is to investigate the association between post-cesarean sonographic uterine measures, dysmenorrhea, and bleeding disorders.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study where 500 women with a history of only one cesarean section (CS) were recruited. A transvaginal transducer, GE RIC6-12-D was used for the acquisition of volumetric datasets 18 ± 7 months postpartum. Uterine length (UL), cervical length (CL), niche length (L), niche depth (D), niche width (W), fibrosis length (FL), fibrosis depth (FD), residual myometrial thickness (RMT), endometrial thickness (EM), scar to internal os distance (SO), anterior myometrial thickness superior (sAMT) and inferior (iAMT) to the scar, and the posterior myometrial thickness opposite the scar (PMT), superior (sPMT), and inferior to it (iPMT) were measured. Logistic regression with odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (CI) and ROC curves were utilized.

Results

The proportion of patients with incident post-cesarean bleeding disorders and dysmenorrhoea was 36% (CI 32%, 40%) and 17% (CI 14%, 21%) respectively. Univariate logistic regression showed that only UL was associated with bleeding disorders [OR 1.04 (CI 1.01,10.7) p value 0.005], whereas dysmenorrhea was associated with RMT [OR 0.82 (CI 0.71,0.95) p value 0.008], SO [OR 0.91 (CI 0.86,0.98) p value 0.01], and RMT ratio [OR 0.98 (CI 0.97,0.99) p value 0.03]. Multivariate logistic regression for dysmenorrhoea including SO and RMT remains statistically significant with p values <0.05 and area under the curve of 0.66.

Conclusion

There is an association between sonographic appearance of CS scars and dysmenorrhoea. Nevertheless, the association is weak and other biological post-cesarean characteristics should be explored as potential causes.

Keywords: Cesarean section, Sonography, Bleeding disorder, Dysmenorrhea, Cesarean scar

What does this study adds to the clinical work

| Despite the association between the sonographic appearance of cesarean scars and dysmenorrhoea and bleeding disorders, the utility of ultrasound in explaining these complaints is clinically limited. |

Introduction

Cesarean section (CS) is one of the most frequently performed surgeries worldwide. The CS rate in Germany doubled in the last 30 years to reach an all-time high of about 30.9% according to a 2023 press release from the Federal Statistical Office of Germany [1]. Many developed countries have CS rates of 30% or more. Despite the fact that CSs are routine and often performed procedures, they increase the risk of adverse maternal outcomes in comparison to vaginal delivery [2]. A history of CS is associated with a serious long-term risk of abnormal uterine bleeding, chronical pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia [3], but the pathogenesis behind these symptoms is not fully understood. The uterine wall incision during CS could heal entirely or leave a defect called a “niche”. The prevalence of a niche greatly varies depending on the selection of the study population (random, symptomatic, or non-symptomatic), the utilized diagnostic tools (transvaginal sonography, contrast-enhanced sonohysterography, or hysteroscopy), the study sample size, and the utilized definition of the diagnostic criteria. Sonographic prevalence ranges from 24 to 70%, and the characteristics and the size of niches are associated with possible gynecological complaints [4, 5]. Menstrual debris is suspected to collect in the uterine wall defects (niche) and delayed emptying of this debris can then cause postmenstrual spotting and intermenstrual bleeding. Moreover, dysfunctional uterine contraction in an attempt to clear the niche of any debris could be the reason for the pelvic pain [6]. Furthermore, a previous CS increases the risk of abnormally invasive placenta, extrauterine pregnancy, uterine rupture, and hysterectomy in a subsequent pregnancy [2]. A better understanding of cesarean scars and their outcomes is crucial to allowing a profound consultation and treatment of women who show any of these symptoms.

Especially after Delphi-based guidelines to standardize the sonographic measurement of niches were published by Jordans et al. in 2019 [7], ultrasound is considered to be the gold standard imaging technique for assessing the condition of the uterine wall and any possible scaring after CS [8]. In addition to measuring length, width, and depth of the niche, other measurements like the residual myometrial thickness (RMT) and the distance between the niche and the external os ought to be taken into consideration as well [9].

The aim of this work is to assess the association between the standardized uterine sonographic measurements after a CS and incident dysmenorrhea and dysfunctional bleeding. Establishing such an association could be beneficial in building predictive models of gynecological complications for women with a history of CS using sonographic features.

Methods

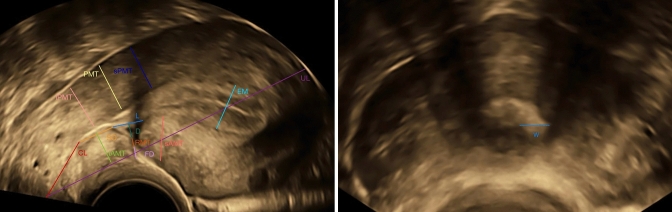

The data utilized in this cross-sectional study were collected within the BSUM study. The BSUM study is a prospective observational multicenter clinical study that included consenting patients over the age of 18 with a history of only one CS and open family planning. Excluded from the study were patients with more than one CS, a history of vertical hysterotomy or additional uterine surgeries as well as completed family planning. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Hessen Regional Medical Council (Reg. No. 2019-1138-evBO). A total of 500 women were recruited and the patients were examined with transvaginal ultrasound in a lithotomy position and with an empty bladder. A Voluson E10 with a 5–13 MHz GE RIC6-12-D microconvex transvaginal transducer was used for the sonographic evaluation. The timing of examination was at least one year postpartum with a mean of 18 ± 7 months. Volumetric three-dimensional data of the uterus were acquired and analyzed offline for measuring uterine length (UL), cervical length (CL), niche length (L), niche depth (D), niche width (W), residual myometrial thickness (RMT), endometrial thickness (EM), scar to internal os distance (SO), anterior myometrial thickness superior (sAMT) and inferior (iAMT) to the scar and the posterior myometrial thickness opposite the scar (PMT), and superior (sPMT) and inferior to it (iPMT) as per the protocol of the BSUM study [10] and shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Transvaginal ultrasound of a post-cesarean uterus with the measures of the study: uterine length (UL), cervical length (CL), niche length (L), niche depth (D), niche width (W), RMT, endometrial thickness (EM), scar to internal os distance (SO), anterior myometrial thickness superior (sAMT) and inferior (iAMT) to the scar and the posterior myometrial thickness opposite the scar (PMT), and superior (sPMT) and inferior to it (iPMT)

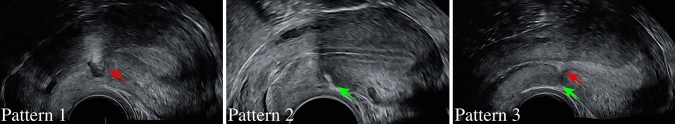

The largest depth of external denting (fibrosis) was measured as (FD) when fibrosis was identified and the uterine scar was classified into three patterns as shown in Fig. 2; pattern 1 showed scars with only a niche, pattern 2 scars with only fibrosis, and pattern 3 scars with both niches and fibrosis.

Fig. 2.

Transvaginal ultrasound showing the typical appearance of the niche (red arrow) and fibrosis (green arrow) among the three patterns of the uterine scar (color figure online)

Moreover, RMT ratio which is the percentage of RMT to the pre-CS anterior wall thickness was calculated according to the formula ‘RMT ratio = RMT × 100/(D + RMT + FD)’ and the volume of the niche was calculated (V = L × D × W). Furthermore, the demographic characteristics and the outcome measures of newly incident dysfunctional uterine bleeding and dysmenorrhea were ascertained at the time of the examination by interviewing the patients and reviewing their medical charts. The outcome measures were based on the standardized nomenclature of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Dysmenorrhea was defined as postsurgical unusually painful menstruation, and dysfunctional uterine bleeding was defined as menstrual flow with volume, duration, frequency, or regularity outside of the individual’s pre-surgical normal [11, 12]. The association between the different sonographic measures as independent variables and the two main outcomes of dysmenorrhea and dysfunctional bleeding as dependent variables was tested with univariate and multivariate logistic regressions, and receiver operating curves were utilized for assessing the performance of the resulting models. The association results from the logistic regression are presented as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) and all statistical analyses were performed with STATA (ver. 18, Texas, USA).

Results

The mean maternal age at delivery was 35.5 ± 5.2 years and 196 (39.2%) of the CSs were elective. The base demographic characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data of the study cohort

| Characteristic | Mean ± SD Median (IQR) Number (percentage %) |

|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 35.5 ± 5.2 |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 38 ± 3.5 |

| Elective cesarean section | 196 (39.2%) |

| Surgical indications | |

| Fetal distress | 125 (25%) |

| Obstructed labor | 103 (20.6%) |

| Breech | 85 (17%) |

| Choice | 32 (6.4%) |

| IUGR | 24 (4.8%) |

| Other | 131(26.2%) |

| Cervical dilatation (cm) | 3 (1–6) |

| Obesity | 29 (5.8%) |

| Antepartal infection | 41 (8.2%) |

| Diabetes | 23 (4.6%) |

SD standard deviation, IQR interquartile range, IUGR intrauterine growth restriction

The questionnaire revealed that 17% (CI 14%, 21%) of women experienced dysmenorrhea while 36% (CI 32%, 40%) of women expressed a struggle with abnormal uterine bleeding after CS. Histograms, quartile–quartile plots, measures of skewness and kurtosis, and Shapiro–Wilk test were utilized to test the assumptions of normality and the distribution of the sonographic findings is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the distribution for all sonographic measurements in mm

| Sonographic finding | Mean ± SD Median (IQR) Number (percentage %) |

|---|---|

| Uterine length (UL)* | 69.06 ± 9.36 |

| Cervical length (CL)* | 20.78 ± 3.7 |

| Residual myometrial thickness (RMT) | 5 (3.2–6.5) |

| Scar to internal os distance (SO)* | 9.79 ± 5.57 |

| Endometrial thickness (EM) | 6.3 (4.2–9) |

| Anterior myometrial thickness superior (sAMT)* | 10.44 ± 2.89 |

| Anterior myometrial thickness inferior (iAMT) | 8.8 (7.5–10.2) |

| Posterior myometrial thickness opposite the scar (PMT) | 11.4 (9.7–13.1) |

| Posterior myometrial thickness superior to scar (sPMT)* | 12.58 ± 3.17 |

| Posterior myometrial thickness inferior to scar (iPMT) | 10.6 (8.8–12.1) |

| Residual myometrial thickness ratio (RMT%) | 57.21 (40.37–71.84) |

| Niche | 405 (81%) |

| Fibrosis | 235 (47%) |

| Volume of the niche | 80.08 (30.09–206.83) |

| Pattern 0 (no scar) | 41 (8.2%) |

| Pattern 1 (niche) | 221 (44.2%) |

| Pattern 2 (fibrosis) | 53 (10.6%) |

| Pattern 3 (both niche and fibrosis) | 185 (37%) |

SD standard deviation, IQR interquartile range

The variables for which the assumptions of normality hold are marked with *

Univariate logistic regression was utilized to show the association between dysmenorrhea as well as bleeding disorders and each sonographic measure as portrayed in Table 3. There was an association between bleeding disorders and UL only [OR 1.04 (CI 1.01, 1.07) p value 0.005]. Dysmenorrhea, on the other hand, showed an association with RMT [OR 0.82 (CI 0.71, 0.95) p value 0.008], SO [OR 0.91 (CI 0.86, 0.98) p value 0.01], and RMT ratio [OR 0.98 (CI 0.97, 0.99) p value 0.03].

Table 3.

Odds ratio with standard error and confidence interval as well as p value for the univariate logistic regression with all sonographic measurements

| Sonographic finding | Bleeding disorders | Dysmenorrhea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | |

| UL | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 0.005 | 1.02 (0.99–1.06) | 0.15 |

| CL | 1.05 (0.98–1.12) | 0.18 | 0.96 (0.89–1.05) | 0.40 |

| RMT | 0.93 (0.84–1.02) | 0.12 | 0.82 (0.71–0.95) | 0.008 |

| SO | 0.97 (0.92–1.01) | 0.13 | 0.91 (0.86–0.98) | 0.01 |

| EM | 1.03 (0.96–1.10) | 0.42 | 1.07 (0.98–1.16) | 0.11 |

| sAMT | 1.02 (0.94–1.11) | 0.59 | 0.94 (0.84 1.05) | 0.28 |

| iAMT | 0.96 (0.85–1.08) | 0.46 | 0.92 (0.79–1.07) | 0.27 |

| PMT | 0.99 (0.91–1.08) | 0.89 | 0.98 (0.87–1.09) | 0.70 |

| sPMT | 0.98 (0.91–1.06) | 0.66 | 0.98 (0.89–1.09) | 0.73 |

| iPMT | 0.99 (0.91–1.09) | 0.9 | 1.01 (0.89–1.14) | 0.91 |

| RMT% | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.11 | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.03 |

| Niche | 0.83 (0.45–1.56) | 0.57 | 2.15 (0.80–5.73) | 0.13 |

| Fibrosis | 1.04 (0.63–1.70) | 0.88 | 0.65 (0.34–1.25) | 0.19 |

| Volume of the niche | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.18 | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.19 |

| Pattern 1 (niche) | 1.71 (0.63–4.66) | 0.29 | 6.55 (0.85–50.8) | 0.07 |

| Pattern 2 (fibrosis) | 2.66 (0.83–8.53) | 0.29 | 3.26 (0.34–31.3) | 0.31 |

| Pattern 3 (niche and fibrosis) | 1.33 (0.48–3.70) | 0.58 | 3.58 (0.45–28.7) | 0.23 |

CI confidence interval, UL uterine length, CL cervical length, RMT residual myometrial thickness, SO scar to internal os distance, EM endometrial thickness, sAMT anterior myometrial thickness superior to the scar, iAMT anterior myometrial thickness inferior to the scar, PMT posterior myometrial thickness opposite the scar, sPMT posterior myometrial thickness superior to the scar, iPMT posterior myometrial thickness inferior to the scar, RMT% residual myometrial thickness ratio. Significant p-values are printed in bold

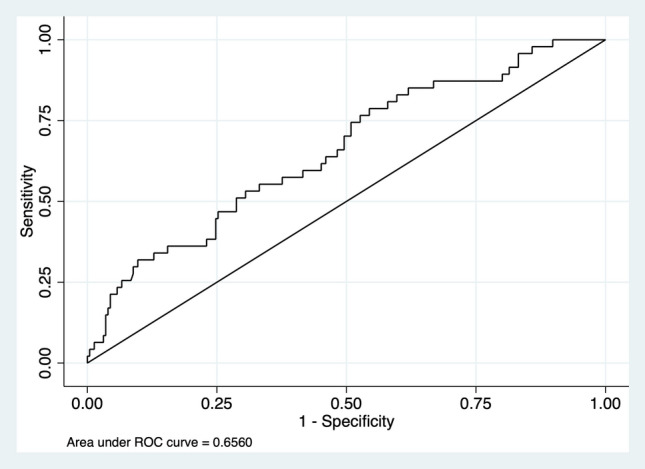

Since dysmenorrhea showed a significant association with more than one variable, and multivariate logistic regression (using RMT and SO) and ROC analysis were performed. The p value of the multivariate logistic regression remained significant with p value <0.05 and the area under the ROC was 0.66 with pseudo R2 of 0.052 as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis for dysmenorrhea predicted by residual myometrial thickness (RMT) and scar to internal os distance (SO)

Discussion

A recently published new nomenclature for cesarean scar disorder (CSDi) can be considered a milestone for the study of CS scars, niches, and post-cesarean complications. The modified Delphi procedure included 31 international niche experts who reached a consensus that CSDi should be used to describe post-cesarean niche-caused abnormal conditions [13]. Defining this diagnosis aimed to standardize the characteristics of this condition since no consistent definition for the combination of sonographic findings and clinical symptoms existed before. CSDi was specified as the presence of a niche, defined according to the guidelines by Jordans et al. [7], combined with either one primary or two secondary symptoms. The primary symptoms include postmenstrual spotting, dysmenorrhea, technical difficulties with catheter insertion during embryo transfer and secondary not otherwise explained infertility combined with intrauterine fluid, whereas dyspareunia, abnormal vaginal discharge, chronic pelvic pain, avoiding sexual intercourse, odor associated with abnormal blood loss, secondary unexplained infertility, infertility despite ART, negative self-image and discomfort during leisure activities are considered as secondary symptoms [13]. Nevertheless, it is essential to exclude other possible causes of the symptoms prior to diagnosing CSDi. The possible long-term outcomes of a CS can greatly impact women’s quality of life, and there is a consensus that many of these outcomes are niche-related but further distinctions remain missing.

The protective role of RMT against gynecological and obstetrical complications after a CS is considered to be essential. A prospective study of more than 300 patients showed that the ratio of niche depth to RMT could be utilized to predict uterine dehiscence in a prospective pregnancy [14]. Moreover, a cohort from Shanghai, with a sample size comparable to ours, showed that women who become symptomatic after CS have thinner RMT and are more likely to show a niche compared to asymptomatic women. They proposed that an RMT of about 5 mm is considered normal for asymptomatic women with satisfactory CS scar healing [15]. The importance of RMT was again emphasized in the niche sonographic evaluation guidelines [7]. Our findings, which showed a significant association between dysmenorrhea and RMT, confirm the importance of RMT during the sonographic CS scar evaluation. Furthermore, we found an association between SO and dysmenorrhea where an increase in SO is associated with a decreased risk of dysmenorrhea. This might indicate that women with unplanned CS, who tend to have smaller SO [16], could have an increased risk of dysmenorrhea compared to women with planned CS. Nevertheless, the resulting pseudo R2 of the multivariate logistic regression demonstrates that only about 5% of the dysmenorrhea cases can be explained by the sonographic findings. Our data highlight that the utility of ultrasound in predicting post-cesarean dysmenorrhea is extremely limited. About 95% of symptomatic patients do not exhibit the expected sonographic features. Therefore, we are unlikely to be solely relying on ultrasound for counseling these patients anytime soon. While there is a link between sonographic depiction of niches and dysmenorrhea, this association is weak such that it should not be seen as the sole explanation. Further biological processes happening in the post-cesarean uterine tissue during its healing might be causal of the CSDi instead of the niche itself. Although the pathophysiology is not fully understood yet, several factors, such as the tissue surrounding the cesarean scar with developing adenomyosis [17, 18], hemorrhaging [17], chronic inflammation [17, 18], as well as an absence of endometrium [18], are discussed as the cause of symptoms like chronical pelvic pain or dysmenorrhea. Adenomyosis is especially considered to be a potential cause of post-cesarean dysmenorrhea without having a clear pathogenesis. It is assumed that during the suturing of the uterine incision endometrial cells might be accidentally injected into the myometrium [18].

The association between dysfunctional bleeding and uterine length was an unexpected finding in our cohort. One could assume that bleeding would rather be associated with the volume of the niche instead, but this assumption is not supported by our data. Thus, our results do not correspond with preexisting studies which found an association between the size of the niche and dysfunctional bleeding [19, 20]. Other biological and genetic characteristics could be causal, and a common explanation for dysfunctional bleeding is the retention of menstrual blood and debris in the niche which the uterus can only discharge slowly due to dysfunctional myometrial contraction in the area of the scar [21]. The scar itself as a source of bleeding is supposedly another possible cause for abnormal bleeding post-cesarean. The formation of abnormal blood vessels in the area of the scar which can than cause somewhat heavy bleeding could explain the symptoms [22].

Not adjusting for the demographic characteristics of our cohort might be considered a limitation of the study, but the main aim of this work is to assess the association between the sonographic findings and clinical presentation. Therefore, adjusting for base demographic characteristics was not required. Despite its limitation, this work has several strengths. Data were collected within the context of a prospective study and the risk of information bias was low. The use of high-frequency matrix transducers and 3D ultrasound for complete visualization of the scar tissue with high-end machines is one of them. Additionally, all sonographic examinations were performed following the latest guidelines, and an adequate time gap between each CS and the examination for this study was allowed so that it is safe to assume that all our patients had fully healed scars prior to ultrasound [23].

In summary, there is no real consensus about the pathophysiology and therefore diagnostic and therapeutic options of post-cesarean gynecological complaints. Our data show some utility of ultrasound to explain dysmenorrhea with RMT as well as the position of the niche within the uterus. Nevertheless, it should be taken into consideration that further biological factors, which cannot be visualized with ultrasound, could cause those symptoms. Therefore, we are unable to solely rely on sonographic findings to help these patients and more data to support preexisting findings and help further grasp the pathophysiology are required. Future immuno-histochemical studies of the CS scars with a search for potential biomarkers present a research opportunity that should be pursued parallel to the sonographic studies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Dr. Senckenberg Foundation, Frankfurt, Germany.

Author contributions

HK: data analysis, manuscript writing. AH: data management. FL: project development. FB: project development. AAN: project development, data collection, manuscript editing.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Not applicable.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

The study has been approved by the Ethics Committee at the Hesse State Chamber of Physicians.

Consent to participate

Written consent is within the inclusion criteria.

Consent for publication

Included in the participation consent.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Destatis (2024) Fast ein Drittel aller Geburten im Jahr 2021 durch Kaiserschnitt. Statistisches Bundesamt. https://www.destatis.de/EN/Press/2023/02/PE23_N009_231.html. Accessed 1 Feb 2024

- 2.Sandall J, Tribe RM, Avery L, Mola G, Visser GH, Homer CS, Gibbons D, Kelly NM, Kennedy HP, Kidanto H, Taylor P, Temmerman M. Short-term and long-term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and children. Lancet. 2018;392:1349–1357. doi: 10.1016/S01406736(18)31930-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang C-B, Chiu W-W-C, Lee C-Y, Sun Y-L, Lin Y-H, Tseng C-J. Cesarean scar defect: correlation between Cesarean section number, defect size, clinical symptoms and uterine position. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34:85–89. doi: 10.1002/uog.6405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bij de Vaate AJM, van der Voet LF, Naji O, Witmer M, Veersema S, Brölmann HAM, Bourne T, Huirne JAF. Prevalence, potential risk factors for development and symptoms related to the presence of uterine niches following Cesarean section: systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;43:372–382. doi: 10.1002/uog.13199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fabres C, Aviles G, De La Jara C, Escalona J, Muñoz JF, Mackenna A, Fernández C, Zegers HF, Fernández E. The Cesarean delivery scar pouch. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22:695–700. doi: 10.7863/jum.2003.22.7.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thurmond AS, Harvey WJ, Smith SA. Cesarean section scar as a cause of abnormal vaginal bleeding: diagnosis by sonohysterography. J Ultrasound Med. 1999;18:13–16. doi: 10.7863/jum.1999.18.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jordans IPM, de Leeuw RA, Stegwee SI, Amso NN, Barri-Soldevila PN, van den Bosch T, Bourne T, Brölmann HAM, Donnez O, Dueholm M, Hehenkamp WJK, Jastrow N, Jurkovic D, Mashiach R, Naji O, Streuli I, Timmerman D, van der Voet LF, Huirne JAF. Sonographic examination of uterine niche in non-pregnant women: a modified Delphi procedure. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019;53:107–115. doi: 10.1002/uog.19049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al NA, Mouzakiti N, Wolnicki B, Louwen F, Bahlmann F. Assessing lateral uterine wall defects and residual myometrial thickness after cesarean section. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;258(391):395. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al NA, Wolnicki B, Mouzakiti N, Reinbach T, Louwen F, Bahlmann F. Anatomy of the sonographic post-cesarean uterus. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2021;304:1485–1491. doi: 10.1007/s00404-02106074-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al NA, Mouzakiti N, Hondrich M, Louwen F, Bahlmann F. The B-mode sonographic evaluation of the post-caesarean uterine wall and its methodology: a study protocol. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2020;46:2547–2551. doi: 10.1111/jog.14492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Practice Bulletin No. 128: Diagnosis of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding in Reproductive-Aged Women (2012) Obstetrics and gynecology (New York. 1953) 120(1):197–206. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318262e320 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Hewitt GD, Gerancher KR (2018) ACOG COMMITTEE OPINION number 760 dysmenorrhea and endometriosis in the adolescent. Obstet Gynecol (New York. 1953) 132(6):E249–E258. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002978 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Klein Meuleman SJM, Murji A, van den Bosch T, Donnez O, Grimbizis G, Saridogan E, Chantraine F, Bourne T, Timmerman D, Huirne JAF, de Leeuw RA. Definition and criteria for diagnosing cesarean scar disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e235321. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.5321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pomorski M, Fuchs T, Zimmer M. Prediction of uterine dehiscence using ultrasonographic parameters of cesarean section scar in the nonpregnant uterus: a prospective observational study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:365. doi: 10.1186/s12884-014-0365-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou X, Zhang T, Qiao H, Zhang Y, Wang X. Evaluation of uterine scar healing by transvaginal ultrasound in 607 nonpregnant women with a history of cesarean section. BMC Women’s Health. 2021;21:199. doi: 10.1186/s12905-021-01337-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al Naimi A, Jennewein L, Mouzakiti N, Louwen F, Bahlmann F. The effect of the onset of labor on the characteristics of the cesarean scar. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022;157(2):322–326. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ewies AAA, Qadri S, Awasthi R, Zanetto U (2022) Caesarean section operation is not associated with myometrial hypertrophy–a prospective cohort study. J Obstet Gynaecol 42(6):2474–2479. 10.1080/01443615.2022.2074787 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Higuchi A, Tsuji S, Nobuta Y, Nakamura A, Katsura D, Amano T, Kimura F, Tanimura S, Murakami T. Histopathological evaluation of cesarean scar defect in women with cesarean scar syndrome. Reprod Med Biol. 2021;21:e12431. doi: 10.1002/rmb2.12431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antila RM, Mäenpää JU, Huhtala HS, Tomás EI, Staff SM. Association of cesarean scar defect with abnormal uterine bleeding: the results of a prospective study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;244:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Voet LF, Bij de Vaate AM, Veersema S, Brölmann HA, Huirne JA (2014) Long-term complications of caesarean section. The niche in the scar: a prospective cohort study on niche prevalence and its relation to abnormal uterine bleeding. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 121(2):236–244. 10.1111/1471-0528.12542 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Bij de Vaate AJM, Brölmann HAM, van der Voet LF, van der Slikke JW, Veersema S, Huirne JAF. Ultrasound evaluation of the Cesarean scar: relation between a niche and postmenstrual spotting. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37:93–99. doi: 10.1002/uog.8864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mariya T, Umemoto M, Sugita N, Suzuki M, Saito T. Recurrent massive uterine bleeding from a Cesarean scar treated successfully by laparoscopic surgery. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2019;8:36–39. doi: 10.4103/GMIT.GMIT_69_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baranov A, Salvesen KÅ, Vikhareva O. Assessment of Cesarean hysterotomy scar before pregnancy and at 11–14 weeks of gestation: a prospective cohort study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50:105–109. doi: 10.1002/uog.16220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.