Editor—Hawton et al highlight the effect of the media on influencing the incidence of deliberate self poisoning.1 However, they and other authors suggest that the changes noted are the result of spontaneous variation in the patterns of particular overdoses rather than a direct effect of the specific televised incident.2,3 One of the limitations of previous studies has been that the investigators have monitored the total numbers of deliberate self poisoning and, specifically, paracetamol overdoses, which are comparatively common. A clearer picture emerges for agents used less commonly for deliberate self harm, such as antifreeze, which commonly contains ethylene glycol or methanol.

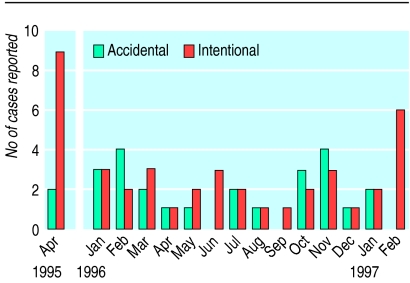

The figure shows the numbers of intentional and accidental cases of poisoning by ethylene glycol reported to the National Poisons Information Service (London) during two specific months and, for comparison, from January 1996 to January 1997. In April 1995 the Independent reported an inquest into an antifreeze poisoning,4 which subsequently received further media coverage. On 15 February 1997 an episode of the BBC television drama Casualty depicted an incident of self harm with ingestion of antifreeze.

The mean number of intentional antifreeze poisonings for 1996 was 2.0 per month (range 1-3 per month). Moreover, the mean number of cases reported during 1995 and 1997, excluding the incident months, was 1.9 and 1.8 respectively. For April 1995 and February 1997 the number of reported cases was 9 and 6—a significant increase (P=0.016). Interestingly, all the cases of intentional ingestion of antifreeze during April 1995 and February 1997 occurred after the announcements in the media. Furthermore, in one specific case not only the agent but also the manner in which the antifreeze was taken (mixed with lemonade and drunk in a field) was identical with that reported.

These data further support the concept that media portrayal of self poisoning influences subsequent self harm behaviour.

Figure.

Numbers of intentional and accidental cases of ethylene glycol posoning reported to the National Poisons Information Service (London)

References

- 1.Hawton K, Simkin S, Deeks JJ, O'Connor S, Keen A, Altman DG, et al. Effects of a drug overdose in a television drama on presentations to hospital for self poisoning: time series and questionnaire study. BMJ. 1999;318:972–977. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7189.972. . (10 April.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Platt S. The aftermath of Angie's overdose: is soap (opera) damaging to your health? BMJ. 1987;294:954–957. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6577.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simkin S, Hawton K, Whitehead L, Fagg J, Eagle M. Media influence on parasuicide. A study of the effects of a television drama portrayal of paracetamol self-poisoning. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167:754–759. doi: 10.1192/bjp.167.6.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spall L. Body found in lane is identified as missing wife. Independent 1995 Apr 15.