Abstract

Introduction

Given the chronic nature of psoriasis (PsO), more studies are needed that directly compare the effectiveness of different biologics over long observation periods. This study compares the effectiveness and durability through 12 months of anti-interleukin (IL)-17A biologics relative to other approved biologics in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis in a real-world setting.

Methods

The Psoriasis Study of Health Outcomes (PSoHO) is an ongoing 3-year, prospective, non-interventional cohort study of 1981 adults with chronic moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis initiating or switching to a new biologic. The study compares the effectiveness of anti-IL-17A biologics with other approved biologics and provides pairwise comparisons of seven individual biologics versus ixekizumab. The primary outcome was defined as the proportion of patients who had at least a 90% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score (PASI90) and/or a score of 0 or 1 in static Physician Global Assessment (sPGA). Secondary objective comparisons included the proportion of patients who achieved PASI90, PASI100, a Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score of 0 or 1, and three different measures of durability of treatment response. Unadjusted response rates are presented alongside the primary analysis, which uses frequentist model averaging (FMA) to evaluate the adjusted comparative effectiveness.

Results

Compared to the other biologics cohort, the anti-IL-17A cohort had a higher response rate (68.0% vs. 65.1%) and significantly higher odds of achieving the primary outcome at month 12. The two cohorts had similar response rates for PASI100 (40.5% and 37.1%) and PASI90 (53.9% and 51.7%) at month 12, with no significant differences between the cohorts in the adjusted analyses. At month 12, the response rates across the individual biologics were 53.5–72.6% for the primary outcome, 27.6–48.3% for PASI100, and 41.7–61.4% for PASI90.

Conclusions

These results show the comparative effectiveness of biologics at 6 and 12 months in the real-world setting.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-023-01086-9.

Keywords: Biologics, Effectiveness, Health outcomes, Interleukin, Ixekizumab, Psoriasis, Real-world evidence

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Plaque psoriasis is a common, chronic inflammatory skin disease that negatively impacts the quality of life of affected individuals. |

| To date, little information exists on the relative effectiveness of biologics for patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis in the real-world setting. |

| To learn about the comparative effectiveness of biologics for 1981 patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis after 6 and 12 months of treatment. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| In the Psoriasis Study of Health Outcomes (PSoHO), the response rates across the individual biologics were 53.5–72.6% for the primary outcome, 27.6–48.3% for Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI)100, and 41.7–61.4% for PASI90 at month 12. |

| These comparative data showing how biologics provide different dynamics of clinical improvement can help to inform the treatment decisions of dermatologists who are faced with comparing numerous approved biologics on a daily basis. |

Introduction

The development of biologic therapies has transformed the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis (PsO) [1, 2]. Yet, the chronic nature of psoriasis necessitates more studies showing the comparative effectiveness of biologics over longer observation periods. In this regard, a major limitation of clinical trials is often the lack of comparator data during extension periods, and head-to-head trials are typically designed to measure efficacy for a period of 1 year or less. Although indirect comparisons partially address this evidence gap [3], they are also limited by the heterogeneity across study designs, homogeneity of patient populations in the included studies, and substantial missing data during longer study periods [4]. Thus, to adequately support physicians in choosing the treatments best suited to the long-term needs of their patients, observational studies are needed that directly compare the long-term effectiveness of approved biologic treatments in patients representing a real-world population [5, 6].

The international, prospective, non-interventional Psoriasis Study of Health Outcomes (PSoHO) was especially designed to investigate the comparative effectiveness of biologic treatments for patients with moderate-to-severe PsO within a real-world setting [6]. This paper presents the 6- and 12-month results for the primary and secondary outcomes. We compare the long-term effectiveness and durability of treatment response of anti-interleukin (IL)-17A biologics with other approved biologics, as well as providing the pairwise comparative effectiveness of ixekizumab (IXE) versus seven other individual biologics.

Methods

PSoHO Study Design

PSoHO is an ongoing, 36-month, prospective non-interventional, cohort study that reflects the treatment of patients with moderate-to-severe PsO with biologics in a real-world setting. A detailed description of the PSoHO study design has been published previously [6]. Prescribed biologics were grouped into either the anti-IL-17A biologics cohort (IXE and secukinumab [SEC]) or a second cohort of other biologics targeting the IL-17 receptor A (brodalumab [BROD]), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (adalimumab [ADA], certolizumab, etanercept, infliximab), IL-23 p19 (guselkumab [GUS], risankizumab [RIS], and tildrakizumab [TILD]), and IL-12/23 p40 (ustekinumab [UST]).

Included Patients

The PSoHO study enrolled 1981 adult patients from 23 countries with a confirmed diagnosis of moderate-to-severe PsO at least 6 months prior to baseline and who initiated or switched biologic treatment during routine medical care.

Study Endpoints

Table 1 provides the definition of the primary outcome of PSoHO. The sPGA is scored on a 6-point scale with a score of 0 or 1 corresponding to clear or almost clear skin. Secondary objective comparisons included the proportion of patients who achieved PASI90, PASI100, and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score of 0 or 1 (Table 1). These outcomes for patients at week 12 were previously published [6] and were similarly assessed at 6 and 12 months post baseline. The DLQI (0,1) outcome only included patients with an available DLQI score of 2 or greater at baseline.

Table 1.

PSoHO effectiveness, quality of life, and durability of effectiveness outcomes and definitions

PASI Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, sPGA static Physician Global Assessment, DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index

Durability of Effectiveness Outcomes

Another secondary objective is the durability of effectiveness, as defined in Table 1. PSoHO also used two further measures of durability of effectiveness, termed the PASI100 durability outcome and PASI90 durability outcome (Table 1).

Statistical Analyses

Unadjusted response rates are reported as proportions of patients and percentages for each outcome. Supplementary Tables 1–3 provide the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the unadjusted response rates. Unadjusted CIs were calculated using the normal approximation. As the primary analysis, a frequentist model averaging (FMA) approach combined multiple analysis strategies to determine adjusted pairwise comparisons between cohorts or individual treatments. The FMA approach controls for potential bias caused by baseline confounders and therefore obtains a more accurate estimate of the treatment effect. An overview of this data-driven methodology has been described previously [6]. Comparative adjusted results are presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% CIs. As a result of the instability and non-convergence of models within the machine learning comparative framework for treatment groups with fewer than 50 patients, pairwise comparisons are only shown for IXE versus SEC, BROD, TILD, GUS, RIS, ADA, and UST.

The main analysis of all patient data applied non-responder imputation (NRI) for patients with missing binary outcomes. A sensitivity analysis applied multiple imputation for all patients with missing data for study outcomes. The statistical appendix provides further details on the FMA application to the multiple imputation approach. A further analysis focused on a subgroup of patients who received the European Medicines Agency (EMA)-approved on-label dosing of included treatments throughout the 12 months and used NRI for missing data.

Study Oversight

All patients provided informed consent for participation in the study. Local ethical review boards approved the protocol, amendments, and consent documentation. The study was registered at European Network of Centres for Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance [7] and was conducted according to Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Patient Characteristics

An earlier publication provides detailed comparisons of baseline demographics and disease characteristics for the 1981 patients included in different treatment groups in the PSoHO study [6]. In short, the demographics and disease characteristics of patients at baseline were comparable between the anti-IL-17A cohort (n = 773) and other biologics cohort (n = 1208), with few exceptions. Patient profiles were also similar across individual treatment groups, with some differences in age, frequency of comorbid PsA, and previous conventional or biologic treatment [6].

Comparison of Anti-IL-17A Cohort Versus Other Biologic Cohort

Effectiveness Outcomes

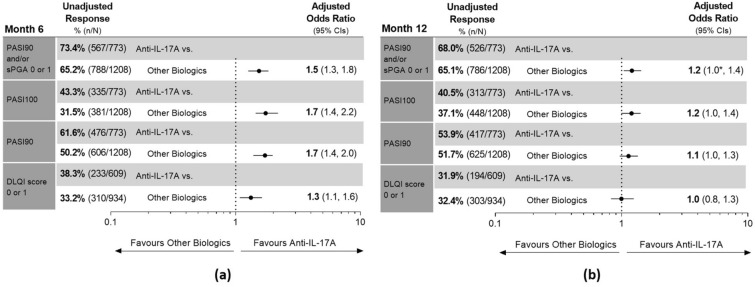

At month 6, the unadjusted response rates for the anti-IL-17A cohort and other biologics cohort were 73.4% and 65.2% for the primary outcome (PASI90 and/or sPGA score of 0 or 1), 43.3% and 31.5% for PASI100, and 61.6% and 50.2% for PASI90 (Fig. 1a). Significantly, the anti-IL-17A cohort had at least 1.5 times higher adjusted odds of achieving these three outcomes at month 6 compared to the other biologics cohort (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Unadjusted response rates and comparative adjusted odds ratio for primary and secondary outcomes for the anti-IL-17A and other biologics cohorts at a month 6 and b month 12. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) outcome only included patients with an available DLQI score of 2 or greater at baseline. For unadjusted and adjusted response rates, patients with missing outcomes were imputed as non-responder imputation (NRI). Adjusted analyses were performed using frequentist model averaging (FMA). Results are statistically significant if 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the odds ratios do not cross 1. For instances that lower CI shows 1.0, *denotes that lower CI is greater than 1. At month 12, the lower CI for the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI)90 and/or Static Physician Global Assessment (sPGA) score of 0 or 1 odds ratio is 1.040, for PASI100 it is 0.995, and for PASI90 it is 0.968. IL interleukin, n number of patients who achieved the outcome, N total number of patients in treatment cohort

At month 12, 68.0% of the anti-IL-17A cohort and 65.1% of the other biologics cohort achieved the primary outcome, for which the anti-IL-17A cohort had significantly higher adjusted odds of achieving this outcome (Fig. 1b). The two cohorts had similar response rates for PASI100 (40.5% and 37.1%) and PASI90 (53.9% and 51.7%) at month 12, with no significant differences between the cohorts in the adjusted analyses (Fig. 1b).

Quality-of-Life Outcome

At month 6, the anti-IL-17A cohort had a greater proportion of patients compared to the other biologics cohort (38.3% and 33.2%) and significantly higher adjusted odds of achieving a DLQI score of 0 or 1 (Fig. 1a). At month 12, the unadjusted response rates for DLQI 0 or 1 were similar between the cohorts (31.9% and 32.4%) and with no significant differences in the adjusted comparative analysis (Fig. 1b).

Durability of Effectiveness Outcomes

For the first durability of effectiveness outcome defined in Table 1, the anti-IL-17A cohort had a greater proportion of patients (53.6% and 41.4%) and significantly higher adjusted odds (OR 1.8) compared to the other biologics cohort (Fig. 2). Similarly for the PASI100 durability outcome (Table 1), the anti-IL-17A cohort had higher response rates (18.2% and 11.5%) and significantly higher odds (OR 1.8) compared to the other biologics cohort. Finally, the anti-IL-17A cohort also had higher response rates (35.3% and 24.7%) and significantly higher odds (OR 1.8) versus the other biologics cohort of achieving the PASI90 durability outcome (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Unadjusted response rates and comparative adjusted odds ratio for three different measures of durability of effectiveness for the anti-IL-17A and other biologics cohorts. Outcomes include (i) durability of effectiveness outcome, whereby patients achieve at least Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI)90 and/or Static Physician Global Assessment (sPGA) score of 0 or 1 at week 12 and subsequently achieve either or both of the following outcomes at months 6 and 12: at least PASI75 or an improvement in sPGA of 2 or more points from baseline; (ii) PASI100 durability outcome, whereby patients achieve a PASI100 score at week 12 and subsequently at both months 6 and 12; (iii) PASI90 durability outcome, whereby patients achieve a PASI90 score at week 12 and subsequently at both months 6 and 12. For unadjusted and adjusted response rates, patients with missing outcomes were imputed as non-responder imputation (NRI). Adjusted analyses were performed using frequentist model averaging (FMA). Results are statistically significant if 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the odds ratios do not cross 1. IL interleukin, n number of patients who achieved the outcome, N total number of patients in treatment cohort

Pairwise Comparisons of Biologics with IXE

Effectiveness Outcomes

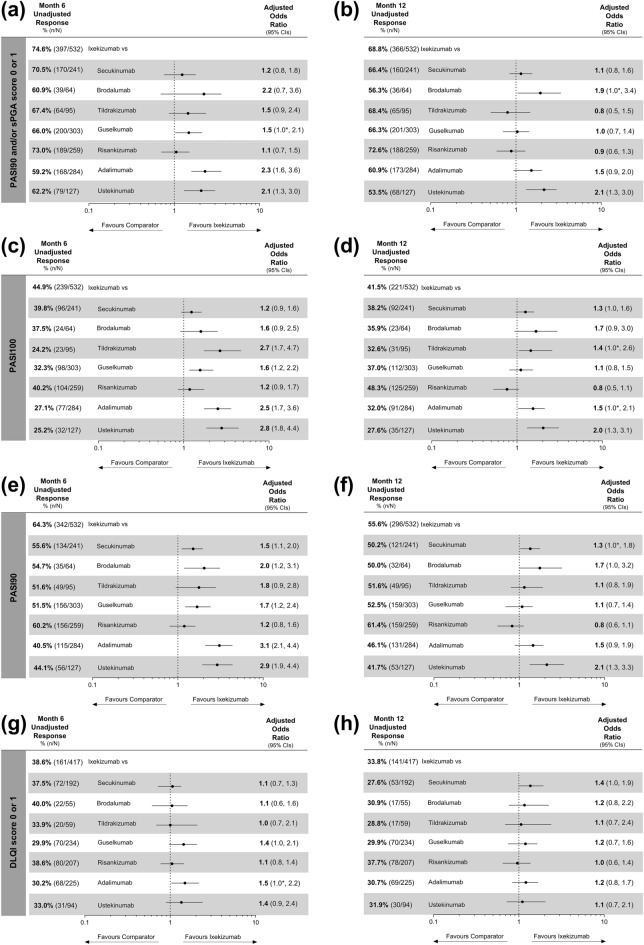

Of all the biologics studied, the proportion of patients who achieved the primary, PASI100 and PASI90 outcomes was highest for IXE at month 6, and RIS at month 12, with the adjusted comparative analyses showing no statistical differences between these two biologics at either timepoint (Fig. 3a–f). For the primary outcome, patients treated with IXE had significantly higher odds compared to GUS, ADA, and UST at month 6 (Fig. 3a) and at month 12 compared to BROD and UST (Fig. 3b). Pairwise comparisons also showed that IXE-treated patients had significantly higher odds of achieving PASI100 than TILD, ADA, and UST at both months 6 and 12, as well as GUS at month 6, but not at month 12 (Fig. 3c, d). Significantly, patients treated with IXE had at least 1.3 times higher odds of achieving PASI90 versus SEC, BROD, GUS, ADA, and UST at month 6, as well as versus SEC and UST at month 12 (Fig. 3e, f).

Fig. 3.

Unadjusted response rates and comparative adjusted odds ratios for primary and secondary outcomes for ixekizumab versus other individual biologics. First row: primary outcome of Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI)90 and/or Static Physician Global Assessment (sPGA) score of 0 or 1 at a month 6 and b month 12. Second row: PASI100 at c month 6 and d month 12. Third row: PASI90 at e month 6 and f month 12. Fourth row: Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score of 0 or 1 at g month 6 and h month 12. DLQI outcome only included patients with an available DLQI score of 2 or greater at baseline. For unadjusted and adjusted response rates, patients with missing outcomes were imputed as non-responder imputation (NRI). Adjusted analyses were performed using frequentist model averaging (FMA). Results are statistically significant if 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the odds ratios do not cross 1. For instances that lower CI shows 1.0, *denotes that the result is significant as lower CI is greater than 1. For the PASI90 and/or sPGA score of 0 or 1 odds ratios, the lower CI for ixekizumab (IXE) vs. guselkumab (GUS) is 1.023 at month 6, and IXE vs. brodalumab (BROD) is 1.047 at month 12. For the PASI100 odds ratios at month 12, the lower CI for IXE vs. secukinumab (SEC) is 0.959, IXE vs. tildrakizumab (TILD) is 1.044 and IXE vs. adalimumab (ADA) is 1.031. For the PASI90 odds ratios at month 12, the lower CI for IXE vs. SEC is 1.027 and IXE vs. BROD is 0.993. For the DLQI (0,1) odds ratios, the lower CI for IXE vs. GUS is 0.967 and IXE vs. ADA is 1.026 at month 6 and IXE vs. SEC is 0.991 at month 12. ADA adalimumab, BROD brodalumab, n number of patients who achieved the outcome, N total number of patients in treatment group, RIS risankizumab, UST ustekinumab

Quality-of-Life Outcome

Except versus ADA at month 6, the adjusted analyses showed no statistically significant differences between IXE and any other biologic for the DLQI (0,1) outcome at either month 6 or 12 (Fig. 3g, h). Across the biologics, the unadjusted response rates ranged from 29.9% to 40.0% at month 6 and 27.6–37.7% at month 12. Between months 6 and 12, the response rates for DLQI (0,1) declined for all biologics except for ADA and GUS, although RIS and IXE maintained the highest response rates (Fig. 3g, h).

Durability of Effectiveness Outcomes

For the first durability of effectiveness outcome (Table 1), IXE-treated patients had the highest response rate (55.8%) and 1.4–3.0 times higher odds of achieving this outcome compared to patients treated with any other biologic (Fig. 4a). Pairwise comparisons also showed that IXE-treated patients had significantly higher odds of maintaining PASI100 or PASI90 from week 12, through months 6 and 12 compared to SEC, TILD, GUS, ADA, and UST, with no significant differences between IXE and BROD or RIS (Fig. 4b, c).

Fig. 4.

Unadjusted response rates and comparative adjusted odds ratios for durability of effectiveness outcomes for ixekizumab versus other individual biologics. Outcomes include a durability of effectiveness outcome, whereby patients achieve at least Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI)90 and/or Static Physician Global Assessment (sPGA) score of 0 or 1 at week 12 and subsequently achieve either or both of the following outcomes at months 6 and 12: at least PASI75 or achieving an improvement in sPGA of 2 or more points from baseline; b PASI100 durability outcome, whereby patients achieve a PASI100 score at week 12 and subsequently at both months 6 and 12; c PASI90 durability outcome, whereby patients achieve a PASI90 score at week 12 and subsequently at both months 6 and 12. For unadjusted and adjusted response rates, patients with missing outcomes were imputed as non-responder imputation (NRI). Adjusted analyses were performed using frequentist model averaging (FMA). Results are statistically significant if 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the odds ratios do not cross 1. For instances that lower CI shows 1.0, *denotes that the result is significant as lower CI is greater than 1. In c the lower CI for ixekizumab (IXE) vs. secukinumab (SEC) odds ratio is 1.013. ADA adalimumab, BROD brodalumab, CI confidence interval, FMA frequentist model averaging, GUS guselkumab, n number of patients who achieved the outcome, N total number of patients in treatment group, NRI non-responder imputation, RIS risankizumab, TILD tildrakizumab, UST ustekinumab

Additional Comparisons

A sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation for missing outcome data for all patients supported the robustness of the results reported herein (Supplementary Figs. S1–S4). In addition, results for the 1678 patients who received the EMA-approved on-label dosing (Supplementary Tables 4–6; Supplementary Figs. S5–S8) were largely comparable to those shown here for all patients included in PSoHO (Supplementary Table 1–3; Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4).

Discussion

Building on the published week 12 data [6], these latest results from the prospective, non-interventional PSoHO study showed that patients with moderate-to-severe PsO in the anti-IL-17A cohort continued to have significantly higher odds versus the other biologics cohort of achieving the primary outcome of PASI90 and/or sPGA score of 0 or 1 at months 6 and 12. Compared to the other biologics cohort, the patients in the anti-IL-17A cohort also had significantly higher odds of achieving PASI100 and PASI90 at month 6, whereas adjusted analyses at month 12 showed no statistically significant difference between the two cohorts for these outcomes. When three different measures of durability of effectiveness from months 3 to 12 were used, the anti-IL-17A cohort consistently had 1.8 times higher odds of demonstrating response durability versus the other biologics cohort.

Considering the individual biologics, the highest unadjusted response rates for the primary, PASI100 and PASI90 outcomes were achieved with IXE and BROD at week 12 [6], IXE followed by RIS at month 6, and RIS followed by IXE after 1 year of treatment. These response dynamics may reflect the differing mechanisms of action between treatment classes, whereby the anti-IL-17A and IL-17RA biologics showed the highest effectiveness at month 6, and the IL-23 biologics and ADA had a slower onset of action and increasing effectiveness to month 12. While these response dynamics reflect the literature that biologics targeting IL-17 cytokines provide the earliest clinical benefit [8], they also show that the high level of effectiveness of anti-IL-17A biologics is durable through 12 months. This is evidenced by the finding that for complete and almost-complete skin clearance, RIS and then IXE provided the greatest clinical benefits at 1 year and that the comparative adjusted analyses showed no significant differences between these two treatments. By completing effectiveness analyses at three different timepoints over the course of 1 year, PSoHO reveals the varying response dynamics of different treatment classes and individual biologics. These data supplement the recently disclosed information on the patients’ perceived improvements of their psoriasis on a weekly basis with different treatments through 12 weeks [9], by revealing the response dynamics of different treatment classes and individual biologics in the longer term. Understanding the dynamics of clinical improvement of biologics in a real-world setting can help to inform the treatment decisions of dermatologists faced with comparing numerous approved biologics on a daily basis [3, 10].

Across the included biologics, the response rates at month 12 ranged from 27.6% to 48.3% for PASI100 and 41.7–61.4% for PASI90, which were in general lower than those recorded in various clinical trials and network meta-analyses (NMAs) [11, 12]. These data may suggest an efficacy-effectiveness gap exists for some of the studied biologics [13–15], but may also result from the conservative approach adopted in PSoHO of imputing missing data as non-response. Similarly, PSoHO reported a much lower and narrower range of DLQI (0,1) response rates compared to those reported in clinical trials over 1 year of biologic treatment [3, 4, 16]. Studies have consistently shown that IL-17A and IL-17RA biologics yield higher DLQI (0,1) responses at week 12 compared to other biologics [17], yet PSoHO facilitated the evaluation of the comparative effect of biologics on patients’ quality of life beyond 12 weeks and in a real-world setting. Overall, with DLQI (0,1) response rates of 29.9–40.0% at month 6 and 27.6–37.7% at month 12, PSoHO showed that the response rates were similar among all biologics, despite the heterogeneity of the pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties of the included biologics. The discrepancy with clinical trial data [11] and reduction in DLQI response rates for many biologics from month 6 to month 12 may reflect a shift in patient expectations over time away from skin clearance and towards other factors affecting quality of life.

Relative to IXE, PASI100 responses with BROD were higher at week 12 [6], but lower through month 12. In alignment with previous research, this trend is likely attributable to the higher discontinuation rate for BROD than IXE and the conservative non-responder imputation approach to handling missing data [18]. Of the anti-IL-17A biologics, IXE showed higher response rates and odds ratios for all outcomes and at all timepoints compared to SEC, which confirms the findings of many long-term NMAs [3, 4, 16]. PSoHO also confirmed the week 12 results from the IXORA-R head-to-head study that showed IXE delivers patients complete skin clearance more rapidly than GUS [19–21]. Although the IXORA-R study showed no difference in efficacy between IXE and GUS at week 24 [3, 22], PSoHO contrarily showed that IXE-treated patients had higher response rates and significantly higher odds of achieving PASI100 and PASI90 at month 6 compared to GUS-treated patients. These differences in treatment effectiveness are unlikely to be attributable to differences in patients’ characteristics in the two treatment groups since PSoHO accounts for potential confounders, such as the higher frequency of biologic-experienced patients in the GUS treatment group [6]. In terms of effectiveness of the different IL-23 inhibitors, a recent real-world study of 233 patients in Italy found that three IL-23 antibodies, GUS, RIS, and TILD, were similarly effective for patients through 28 weeks [23]. In contrast, the global PSoHO study of 1981 patients found that RIS showed higher response rates for all outcomes compared to GUS and TILD. Although the reasons for this variability are unclear, these results may be attributable to differences in patients’ baseline characteristics, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, or dosing frequency [19–21]. These individual treatment effectiveness analyses confirm the importance of considering treatments individually, as biologics within a treatment class are not equally effective [3].

Various studies have posited that certain patients respond more rapidly and maintain high-level skin responses to treatment, which has given rise to the term “super responders” [24]. In the context of psoriasis, there are varied definitions of a super responder without consensus [24–26]. According to the literature, super responders are reported to be younger, biologic-naive patients with an earlier disease onset and with lower rates of obesity, and diabetes mellitus [24]. Adjusting for many of these potentially confounding factors, PSoHO compared biologics using a more stringent assessment of “super response” than previously studies have applied [6, 10], namely the achievement of PASI100 at week 12 and maintenance of this response at both months 6 and 12. Unadjusted analyses showed IXE, BROD, and RIS had the highest response rates ranging from 18% to 20% and with adjusted analyses showing no significant difference between IXE and either BROD or RIS. Significantly, patients treated with IXE had higher odds of achieving this PASI100 durability outcome, as well as the PASI90 durability outcome versus SEC, GUS, TILD, ADA, and UST. Taken together, PSoHO’s comparative, real-world data indicates that the durability of high-level responses or “super response” over 1 year is not a characteristic inherent to specific classes of biologic but rather relies on the specific properties exhibited by each individual biologic.

Despite some differences in PASI outcomes between biologic treatment classes, these data do not determine one particular mechanism of action as superior in terms of high-level skin responses. Rather, these real-world findings indicate that modern, last-generation biologics have similar effectiveness at month 12 [3, 22]. As such, clinicians should choose a more comprehensive approach and consider additional criteria, such as speed of clinical improvement, effectiveness in special areas, and the patient’s demographic and disease profile [2, 27, 28]. For example, previous PSoHO data showed that a patient’s clinical response to some treatments may be affected by the presence of comorbid PsA, prior exposure to biologics [5], or psoriasis localized in specific areas of the body [29]. Aligning treatment choice with the patient’s expectations and needs is also critical, with PSoHO comparative data showing the variability across biologics in patient-reported improvements in psoriasis signs and symptoms [9].

Limitations of this study include the grouping of non-anti-IL-17A biologics into a single category and that pairwise comparisons of individual treatment effectiveness were completed relative to IXE only. With respect to the analyses, the highest proportion of patients were prescribed IXE translating to higher statistical precision, whereas some of the treatment groups contained low patient numbers, leading to less stability of models and broader confidence intervals. While generalizability is increased by having multiple centers across many countries, different countries may have various levels of access to treatment and not all treatments are registered or reimbursed in different countries, increasing the variability within some treatment groups. As a prospective, observational study with non-randomized treatment selection, PSoHO is subject to various forms of bias, including selection bias that may result in confounding, participation bias, and measurement error. However, the application of the machine-learning FMA statistical methodology in PSoHO is a strength of this study as it mitigates some of the typical limitations of observational trials, including confounding that can result in selection and other forms of bias. See statistical appendix for further details.

Conclusion

Building on the 12-week PSoHO data [6], these latest results directly compare the long-term effectiveness and durability of different biologics through 12 months for patients with moderate-to-severe PsO in the real-world setting.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants, caregivers, and investigators of this study.

Medical Writing Assistance

The authors also thank Caroline Murphy and Dominika Kennedy of Eli Lilly and Company for their help preparing figures and tables.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Christopher Schuster; Methodology: Christopher Schuster, Alan Brnabic, Anastasia Lampropoulou, Natalie Haustrup; Statistical analysis: Alan Brnabic, Ilya Lipkovich and Zbigniew Kadziola; Writing: Natalie Haustrup, Christopher Schuster, Alan Brnabic, Ilya Lipkovich and Zbigniew Kadziola; Interpretation and critical review: Andreas Pinter, Antonio Costanzo, Saakshi Khattri, Saxon Smith, Jose-Manuel Carrascosa, Yayoi Tada, Elisabeth Riedl, Adam Reich, Carle Paul, Natalie Haustrup, Anastasia Lampropoulou, Ilya Lipkovich, Zbigniew Kadziola, Alan Brnabic, Christopher Schuster. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Funding

This study and Rapid Service Fee are sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the study, after anonymization. Data are available to request after primary publication acceptance. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Andreas Pinter has served as an investigator, speaker, and/or consultant for AbbVie, Almirall-Hermal, Amgen, Biogen Idec, BioNTech, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, GSK, Eli Lilly and Company, Galderma, Hexal, Janssen, LEO Pharma, MC2, Medac, Merck Serono, Mitsubishi, MSD, Novartis, Pascoe, Pfizer, Tigercat Pharma, Regeneron, Roche, Sandoz Biopharmaceuticals, Sanofi Genzyme, Schering-Plough and UCB Pharma. Antonio Costanzo served as advisory board member and consultant, and/or has received fees and/or speaker’s honoraria and/or has participated to clinical trials for Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Novartis, Sanofi and UCB and is president of European Dermatology Forum and has received payment to participate on the advisory boards for IQVIA. Saakshi Khattri reports grants from Pfizer, Incyte and Acelyrin and has worked as a consultant and/or served on the speaker’s bureau for Abbvie, Arcutis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi and UCB Pharma. Adam Reich has worked as a consultant or speaker for Abbvie, Bausch Health, Bioderma, Celgene, Chema Elektromet, Eli Lilly and Company, Galderma, Janssen, LeoPharma, Medac, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Trevi and Sandoz and participated as principal investigator or sub-investigator in clinical trials sponsored by AnaptysBio, Arcutis, Argenx, Biothera, Celltrion, Drug delivery solutions, Galderma, Genentech, Inflarx, Incyte, Janssen, Kymab Limited, LeoPharma, Menlo Therapeutics, MetrioPharm, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Eli Lilly and Company, UCB and VielaBio. Jose-Manuel Carrascosa, reports grants, personal fees, participation on advisory boards and/or non-financial support from Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Novartis, Sandoz, Leo-pharma. Saxon Smit has worked as an advisor and/or speaker for Abbvie, UCB, Sanofi Gezyme, Novartis, Eli Lilly and Company, BMS and Pfizer; and participated in data safety monitoring board or advisory boards for BMS, Novartis, Eli Lilly and Company, Abbvie, Sanofi Genzyme, Leo Pharma, UCB and Amgen. Yayoi Tada reports grants from AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai, Eli Lilly and Company, Jimro, Kaken, Kyowa Kirin, LEO Pharma, Maruho, Meiji Seika Pharma, Sun Pharma, Taiho, Tanabe-Mitsubishi, Torii, and UCB and has received honoraria for speaking events from AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen Pharma, Jimro, Kyowa Kirin, LEO Pharma, Maruho, Novartis Pharma, Sun Pharma, Taiho, Tanabe-Mitsubishi, Torii, and UCB. Elisabeth Riedl is a former employee, minor stockholder and has pending patents with Eli Lilly and Company and has also been a speaker and/or consultant for Eli Lilly and Company and Pehpharma. Carle Paul has served as a consultant for Almirall, Abbvie, Amgen, BMS, Boeheringer Ingelheim, Celgene, GSK, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi and UCB; received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Janssen; participated on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board with IQVIA (DSMB). Alan Brnabic, Anastasia Lampropoulou, Natalie Haustrup, Ilya Lipkovich, Zbigniew Kadziola, and Christopher Schuster are all employees and minor shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company.

Ethics Approval

The protocol, amendments, and consent documentation were approved by local institutional review boards (IRB). The study was registered at the European Network of Centers for Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance (ENCEPP24207) and was conducted according to International Conference on Harmonization, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients were required to give informed consent for participation in the study. We confirm that the necessary central or local IRB and/or ethics committee approvals have been obtained for this multi-site, international study by United BioSource LLC (UBC). Approvals can be provided on request.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised: Few text corrections, corrections in table updated in proofs.

Change history

5/30/2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s13555-024-01105-3

References

- 1.Curmin R, Guillo S, De Rycke Y, et al. Switches between biologics in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: results from the French cohort PSOBIOTEQ. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:2101–2112. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dave R, Alkeswani A. An overview of biologics for psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:1246–1247. doi: 10.36849/JDD.6040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Augustin M, Schuster C, Mert C, et al. The value of indirect comparisons of systemic biologics for psoriasis: interpretation of efficacy findings. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2022;12:1711–1727. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00765-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nast A, Dressler C, Schuster C, et al. Methods used for indirect comparisons of systemic treatments for psoriasis. A systematic review. Skin Health Dis. 2023;3:e112. doi: 10.1002/ski2.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lynde C, Riedl E, Maul J-T, et al. Comparative effectiveness of biologics across subgroups of patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results at week 12 from the PSoHO study in a real-world setting. Adv Ther. 2023;40(3):869–86. doi: 10.1007/s12325-022-02379-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinter A, Puig L, Schäkel K, et al. Comparative effectiveness of biologics in clinical practice: week 12 primary outcomes from an international observational psoriasis study of health outcomes (PSoHO) J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(11):2087–2100. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.European Medicines Agency. Psoriasis Study of Health Outcomes—an international observational study of 3 year health outcomes in the biologic treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. ENCePP. https://www.encepp.eu/encepp/viewResource.htm?id=25115. EUPAS24207. 2018.

- 8.Tada Y, Watanabe R, Noma H, et al. Short-term effectiveness of biologics in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;99:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2020.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reich A, Pinter A, Maul JT, et al. Speed of clinical improvement in the real-world setting from patient-reported psoriasis symptoms and signs diary (PSSD): secondary outcomes from the psoriasis study of health outcomes (PSoHO) through 12 weeks. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(9):1825–40. doi: 10.1111/jdv.19161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warren RB, See K, Burge R, et al. Rapid response of biologic treatments of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a comprehensive investigation using Bayesian and frequentist network meta-analyses. Dermatol Ther. 2020;10:73–86. doi: 10.1007/s13555-019-00337-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yasmeen N, Sawyer LM, Malottki K, et al. Targeted therapies for patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of PASI response at 1 year. J Dermatol Treat. 2022;33:204–218. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1743811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armstrong A, Fahrbach K, Leonardi C, et al. Efficacy of bimekizumab and other biologics in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a systematic literature review and a network meta-analysis. Dermatol Ther. 2022;12:1777–1792. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00760-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nordon C, Karcher H, Groenwold RH, et al. The “efficacy-effectiveness gap”: historical background and current conceptualization. Value Health. 2016;19:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia-Doval I, Carretero G, Vanaclocha F, et al. Risk of serious adverse events associated with biologic and nonbiologic psoriasis systemic therapy: patients ineligible vs eligible for randomized controlled trials. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:463–470. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.2768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mason KJ, Barker JN, Smith CH, et al. Comparison of drug discontinuation, effectiveness, and safety between clinical trial eligible and ineligible patients in BADBIR. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:581–588. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Augustin M, Valencia López M, Reich K. Network meta-analyses in psoriasis: overview and critical discussion. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:2367–2376. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blauvelt A, Papp K, Gottlieb A, et al. A head-to-head comparison of ixekizumab vs. guselkumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: 12-week efficacy, safety and speed of response from a randomized, double-blinded trial. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:1348–1358. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Megna M, Potestio L, Camela E, et al. Ixekizumab and brodalumab indirect comparison in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis: results from an Italian single-center retrospective study in a real-life setting. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15667. doi: 10.1111/dth.15667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papp K, Paul C, Kleyn CE, et al. Time to loss of response following withdrawal of ixekizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Acta Dermato-Venereol. 2022;102:adv00672-adv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Daniele S, Eldirany SA, Ho M, et al. Structural basis for differential p19 targeting by IL-23 biologics. bioRxiv 2023:2023.03.09.531913.

- 21.Eldirany SA, Ho M, Bunick CG. Focus: skin: structural basis for how biologic medicines bind their targets in psoriasis therapy. Yale J Biol Med. 2020;93:19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blauvelt A, Gooderham M, Griffiths CEM, et al. Cumulative clinical benefits of biologics in the treatment of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis over 1 year: a network meta-analysis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2022;12:727–740. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00690-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gargiulo L, Ibba L, Malagoli P, et al. Real-life effectiveness and safety of guselkumab in patients with psoriasis who have an inadequate response to ustekinumab: a 104-week multicenter retrospective study-IL PSO (ITALIAN LANDSCAPE PSORIASIS) J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(5):1017–27. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mastorino L, Susca S, Cariti C, et al. “Superresponders” at biologic treatment for psoriasis: a comparative study among IL17 and Il23 inhibitors. Exp Dermatol. 2023;32(12):2187–88. doi: 10.1111/exd.14731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruiz-Villaverde R, Vasquez-Chinchay F, Rodriguez-Fernandez-Freire L, et al. Super-responders in moderate–severe psoriasis under guselkumab treatment: myths, realities and future perspectives. Life. 2022;12:1412. doi: 10.3390/life12091412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schäkel K, Reich K, Asadullah K, et al. Early disease intervention with guselkumab in psoriasis leads to a higher rate of stable complete skin clearance (‘clinical super response’): Week 28 results from the ongoing phase IIIb randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, GUIDE study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(10):2016–2027. doi: 10.1111/jdv.19236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di Cesare A, Ricceri F, Rosi E, et al. Therapy of PsO in special subsets of patients. Biomedicines. 2022;10:2879. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10112879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaushik SB, Lebwohl MG. Psoriasis: which therapy for which patient: focus on special populations and chronic infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piaserico S, Riedl E, Pavlovsky L, et al. Comparative effectiveness of biologics for patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis and special area involvement: week 12 results from the observational Psoriasis Study of Health Outcomes (PSoHO) Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1185523. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1185523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCaffrey DF, Griffin BA, Almirall D, et al. A tutorial on propensity score estimation for multiple treatments using generalized boosted models. Stat Med. 2013;32:3388–3414. doi: 10.1002/sim.5753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zou H, Hastie T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Statistical Methodology) 2005;67:301–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9868.2005.00503.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the Lasso. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Methodol) 1996;58:267–288. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1996.tb02080.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zagar A, Kadziola Z, Lipkovich I, et al. Evaluating bias control strategies in observational studies using frequentist model averaging. J Biopharm Stat. 2022;32:247–276. doi: 10.1080/10543406.2021.1998095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res. 2007;16:219–242. doi: 10.1177/0962280206074463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Buuren S. Flexible imputation of missing data. 2. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the study, after anonymization. Data are available to request after primary publication acceptance. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.