Abstract

Review Rationale and Context

Many intervention studies of summer programmes examine their impact on employment and education outcomes, however there is growing interest in their effect on young people's offending outcomes. Evidence on summer employment programmes shows promise on this but has not yet been synthesised. This report fills this evidence gap through a systematic review and meta‐analysis, covering summer education and summer employment programmes as their contexts and mechanisms are often similar.

Research Objective

The objective is to provide evidence on the extent to which summer programmes impact the outcomes of disadvantaged or ‘at risk’ young people.

Methods

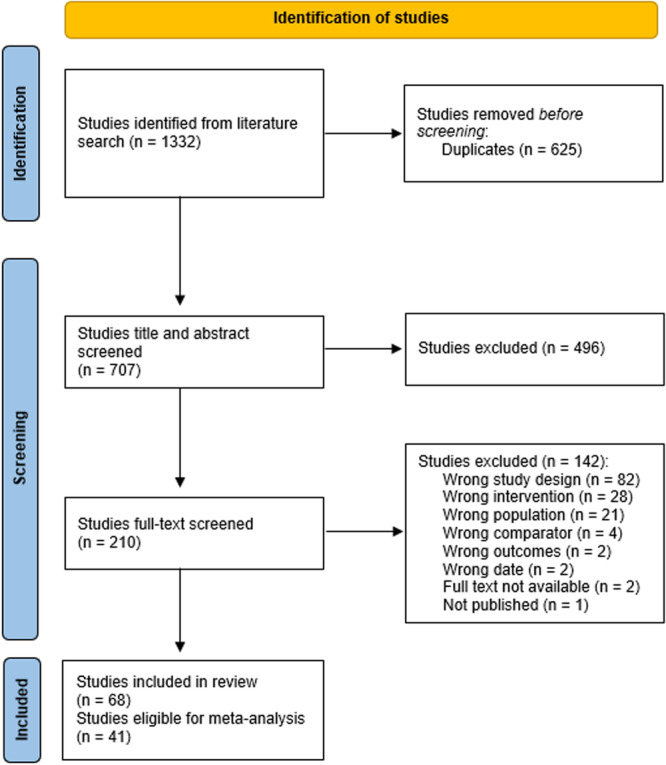

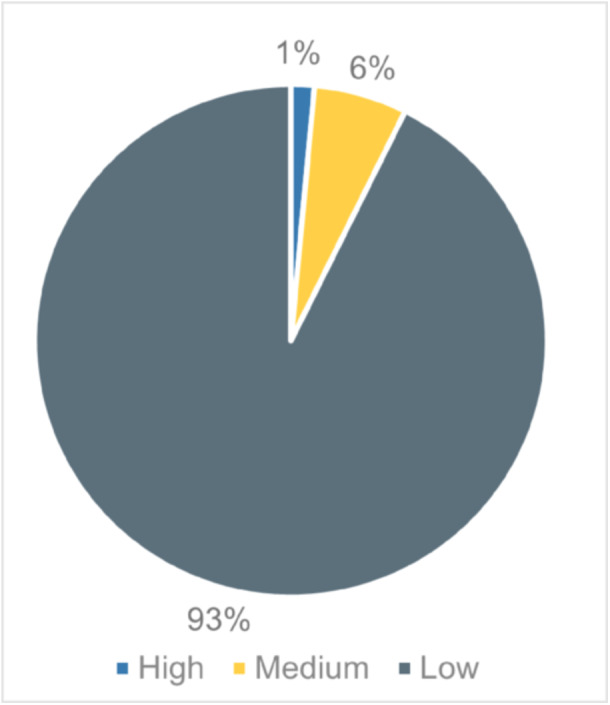

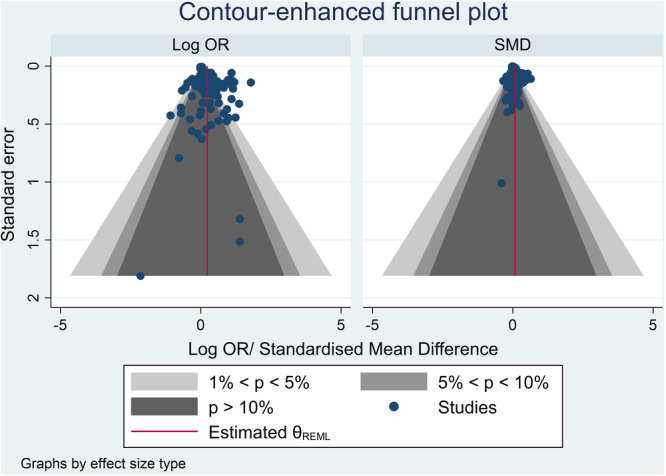

The review employs mixed methods: we synthesise quantitative information estimating the impact of summer programme allocation/participation across the outcome domains through meta‐analysis using the random‐effects model; and we synthesise qualitative information relating to contexts, features, mechanisms and implementation issues through thematic synthesis. Literature searches were largely conducted in January 2023. Databases searched include: Scopus; PsychInfo; ERIC; the YFF‐EGM; EEF's and TASO's toolkits; RAND's summer programmes evidence review; key academic journals; and Google Scholar. The review employed PICOSS eligibility criteria: the population was disadvantaged or ‘at risk’ young people aged 10–25; interventions were either summer education or employment programmes; a valid comparison group that did not experience a summer programme was required; studies had to estimate the summer programme's impact on violence and offending, education, employment, socio‐emotional and/or health outcomes; eligible study designs were experimental and quasi‐experimental; eligible settings were high‐income countries. Other eligibility criteria included publication in English, between 2012 and 2022. Process/qualitative evaluations associated with eligible impact studies or of UK‐based interventions were also included; the latter given the interests of the sponsors. We used standard methodological procedures expected by The Campbell Collaboration. The search identified 68 eligible studies; with 41 eligible for meta‐analysis. Forty‐nine studies evaluated 36 summer education programmes, and 19 studies evaluated six summer employment programmes. The number of participants within these studies ranged from less than 100 to nearly 300,000. The PICOSS criteria affects the external applicability of the body of evidence – allowances made regarding study design to prioritise evidence on UK‐based interventions limits our ability to assess impact for some interventions. The risk of bias assessment categorised approximately 75% of the impact evaluations as low quality, due to attrition, losses to follow up, interventions having low take‐up rates, or where allocation might introduce selection bias. As such, intention‐to‐treat analyses are prioritised. The quality assessment rated 93% of qualitative studies as low quality often due to not employing rigorous qualitative methodologies. These results highlight the need to improve the evidence.

Results and Conclusions

Quantitative synthesis The quantitative synthesis examined impact estimates across 34 outcomes, through meta‐analysis (22) or in narrative form (12). We summarise below the findings where meta‐analysis was possible, along with the researchers' judgement of the security of the findings (high, moderate or low). This was based on the number and study‐design quality of studies evaluating the outcome; the consistency of findings; the similarity in specific outcome measures used; and any other specific issues which might affect our confidence in the summary findings.

Below we summarise the findings from the meta‐analyses conducted to assess the impact of allocation to/participation in summer education and employment programmes (findings in relation to other outcomes are also discussed in the main body, but due to the low number of studies evaluating these, meta‐analysis was not performed). We only cover the pooled results for the two programme types where there are not clear differences in findings between summer education and summer employment programmes, so as to avoid potentially attributing any impact to both summer programme types when this is not the case. We list the outcome measure, the average effect size type (i.e., whether a standardised mean difference (SMD) or log odds ratio), which programme type the finding is in relation to and then the average effect size along with its 95% confidence interval and the interpretation of the finding, that is, whether there appears to be a significant impact and in which direction (positive or negative, clarifying instances where a negative impact is beneficial). In some instances there may be a discrepancy between the 95% confidence interval and whether we determine there to be a significant impact, which will be due to the specifics of the process for constructing the effect sizes used in the meta‐analysis. We then list the I 2 statistic and the p‐value from the homogeneity test as indications of the presence of heterogeneity. As the sample size used in the analysis are often small and the homogeneity test is known to be under‐powered with small sample sizes, it may not detect statistically significant heterogeneity when it is in fact present. As such, a 90% confidence level threshold should generally be used when interpreting this with regard to the meta‐analyses below. The presence of effect size heterogeneity affects the extent to which the average effects size is applicable to all interventions of that summer programme type. We also provide an assessment of the relative confidence we have in the generalisability of the overall finding (low, moderate or high) – some of the overall findings are based on a small sample of studies, the studies evaluating the outcome may be of low quality, there may be wide variation in findings among the studies evaluating the outcome, or there may be specific aspects of the impact estimates included or the effect sizes constructed that affect the generalisability of the headline finding. These issues are detailed in full in the main body of the review.

-

–

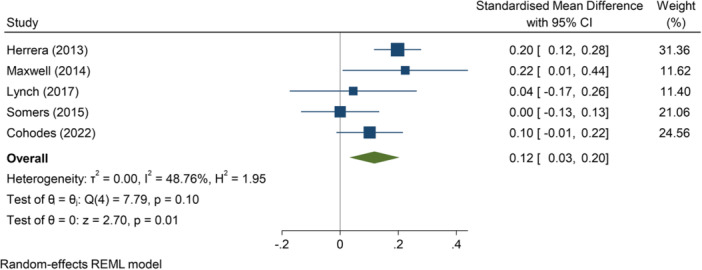

Engagement with/participation in/enjoyment of education (SMD):

-

∘

Summer education programmes: +0.12 (+0.03, +0.20); positive impact; I 2 = 48.76%, p = 0.10; moderate confidence.

-

∘

-

–

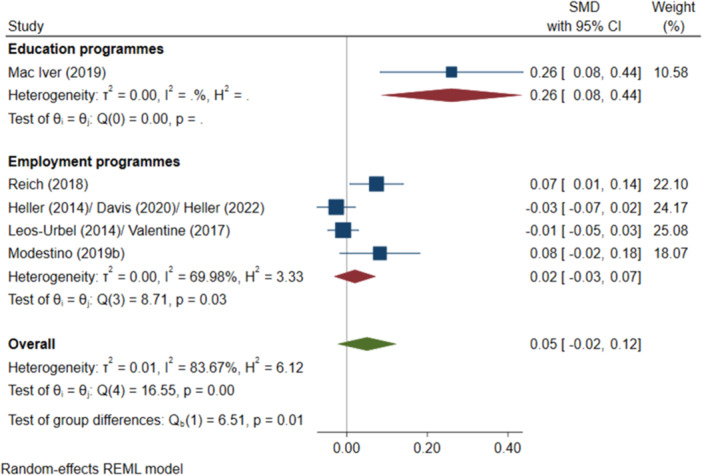

Secondary education attendance (SMD):

-

∘

Summer education programmes: +0.26 (+0.08, +0.44); positive impact; I 2 = N/A; p = N/A; low confidence.

-

∘

Summer employment programmes: +0.02 (−0.03, +0.07); no impact; I 2 = 69.98%; p = 0.03; low confidence.

-

∘

-

–

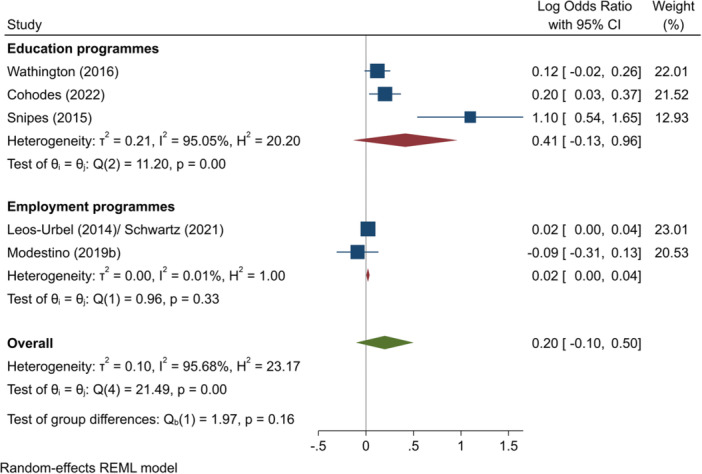

Passing tests (log OR):

-

∘

Summer education programmes: +0.41 (−0.13, +0.96); no impact; I 2 = 95.05%; p = 0.00; low confidence.

-

∘

Summer employment programmes: +0.02 (+0.00, +0.04); positive impact; I 2 = 0.01%; p = 0.33; low confidence.

-

∘

-

–

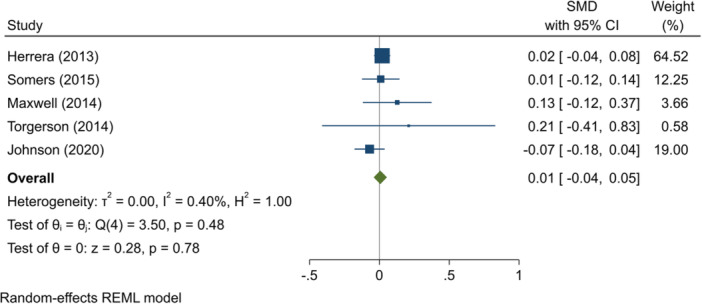

Reading test scores (SMD):

-

∘

Summer education programmes: +0.01 (−0.04, +0.05); no impact; I 2 = 0.40%; p = 0.48; high confidence.

-

∘

-

–

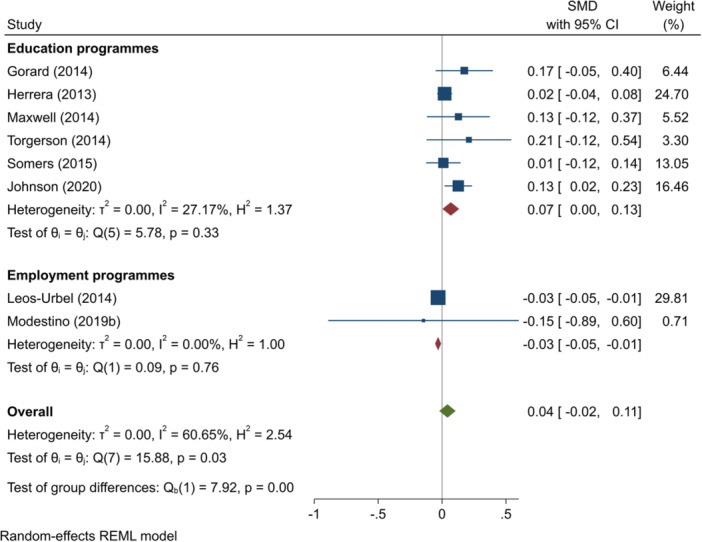

English test scores (SMD):

-

∘

Summer education programmes: +0.07 (+0.00, +0.13); positive impact; I 2 = 27.17%; p = 0.33; moderate confidence.

-

∘

Summer employment programmes: −0.03 (−0.05, −0.01); negative impact; I 2 = 0.00%; p = 0.76; low confidence.

-

∘

-

–

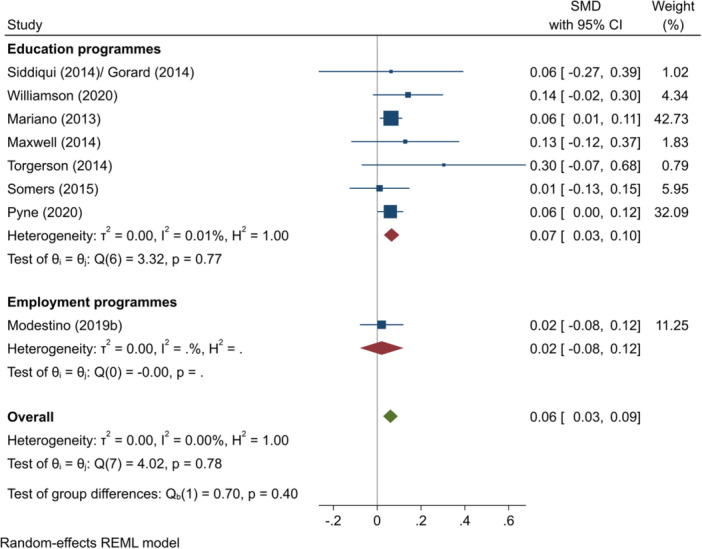

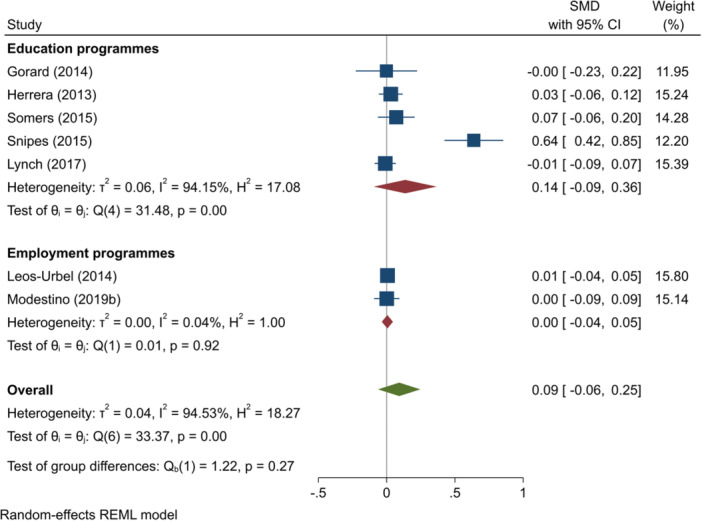

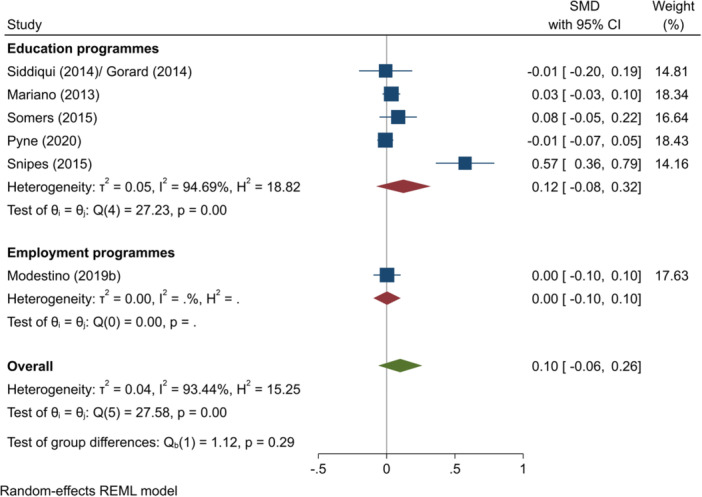

Mathematics test scores (SMD):

-

∘

All summer programmes: +0.09 (−0.06, +0.25); no impact; I 2 = 94.53%; p = 0.00; high confidence.

-

∘

Summer education programmes: +0.14 (−0.09, +0.36); no impact; I 2 = 94.15%; p = 0.00; moderate confidence.

-

∘

Summer employment programmes: +0.00 (−0.04, +0.05); no impact; I 2 = 0.04%; p = 0.92; moderate confidence.

-

∘

-

–

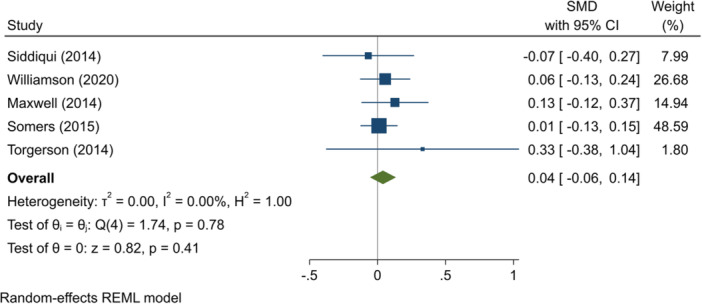

Overall test scores (SMD):

-

∘

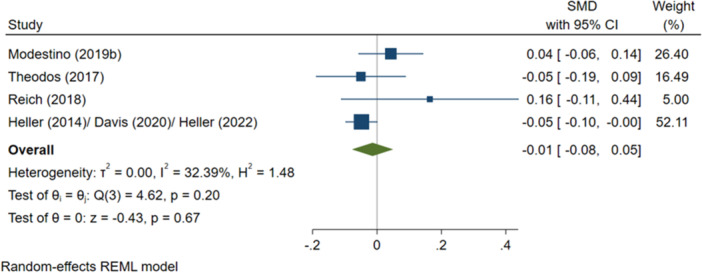

Summer employment programmes: −0.01 (−0.08, +0.05); no impact; I 2 = 32.39%; p = 0.20; high confidence.

-

∘

-

–

All test scores (SMD):

-

∘

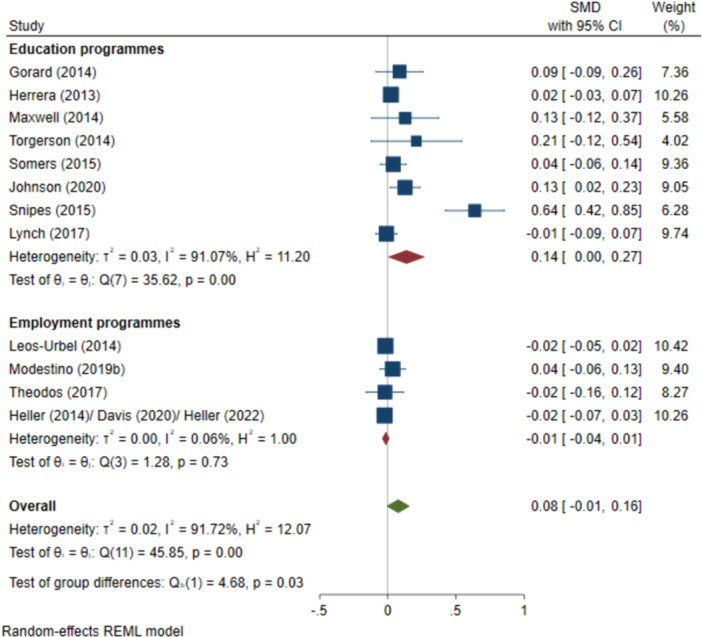

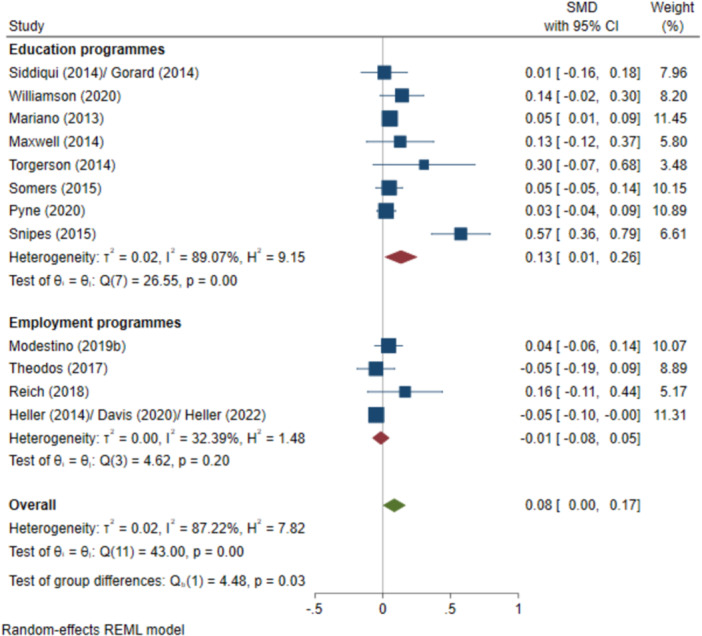

Summer education programmes: +0.14 (+0.00, +0.27); positive impact; I 2 = 91.07%; p = 0.00; moderate confidence.

-

∘

Summer employment programmes: −0.01 (−0.04, +0.01); no impact; I 2 = 0.06%; p = 0.73; high confidence.

-

∘

-

–

Negative behavioural outcomes (log OR):

-

∘

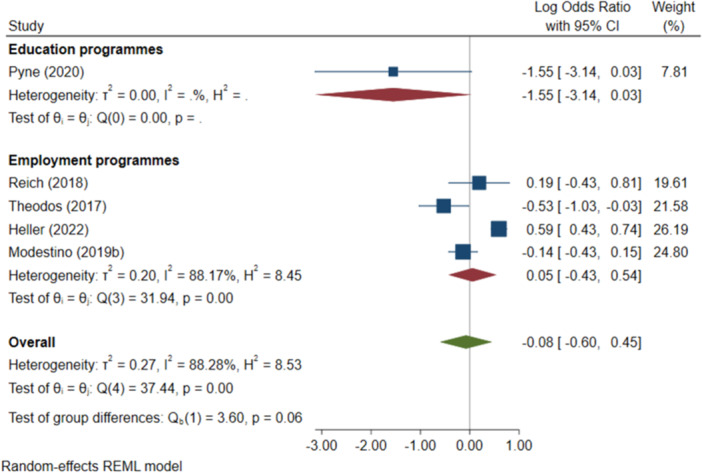

Summer education programmes: −1.55 (−3.14, +0.03); negative impact; I 2 = N/A; p = N/A; low confidence.

-

∘

Summer employment programmes: −0.07 (−0.33, +0.18); no impact; I 2 = 88.17%; p = 0.00; moderate confidence.

-

∘

-

–

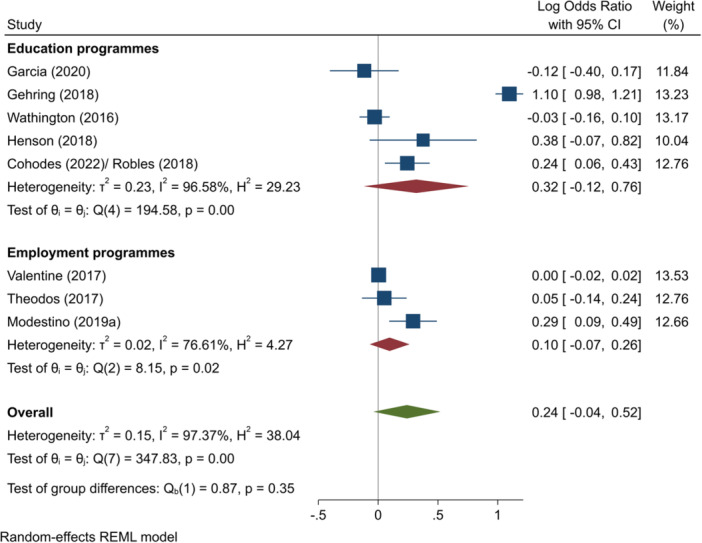

Progression to HE (log OR):

-

∘

All summer programmes: +0.24 (−0.04, +0.52); no impact; I 2 = 97.37%; p = 0.00; low confidence.

-

∘

Summer education programmes: +0.32 (−0.12, +0.76); no impact; I 2 = 96.58%; p = 0.00; low confidence.

-

∘

Summer employment programmes: +0.10 (−0.07, +0.26); no impact; I 2 = 76.61%; p = 0.02; moderate confidence.

-

∘

-

–

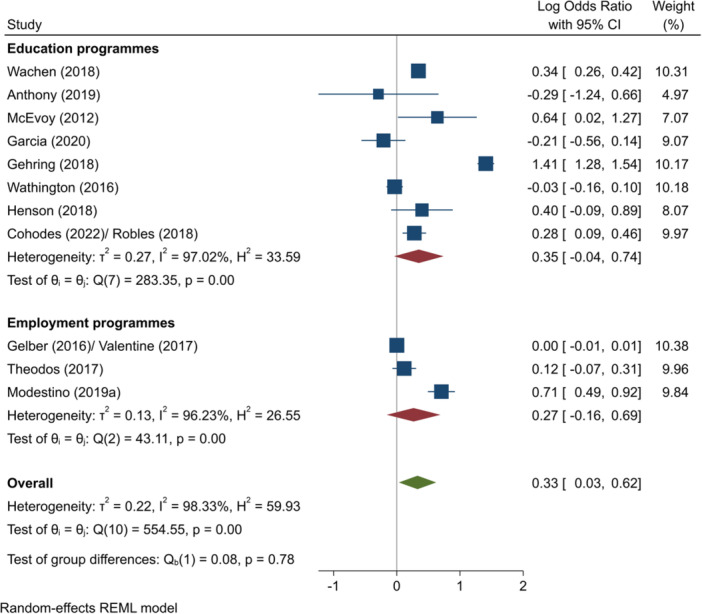

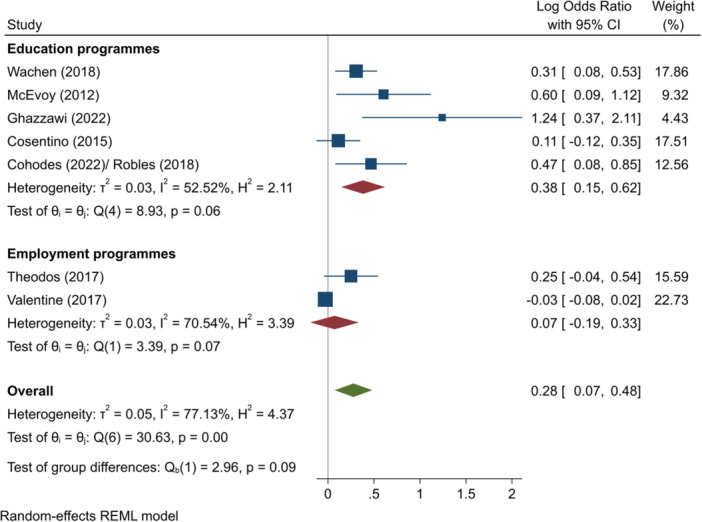

Complete HE (log OR):

-

∘

Summer education programmes: +0.38 (+0.15, +0.62); positive impact; I 2 = 52.52%; p = 0.06; high confidence.

-

∘

Summer employment programmes: +0.07 (−0.19, +0.33); no impact; I 2 = 70.54%; p = 0.07; moderate confidence.

-

∘

-

–

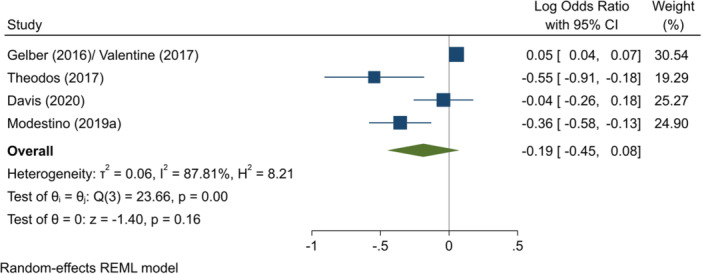

Entry to employment, short‐term (log OR):

-

∘

Summer employment programmes: −0.19 (−0.45, +0.08); no impact; I 2 = 87.81%; p = 0.00; low confidence.

-

∘

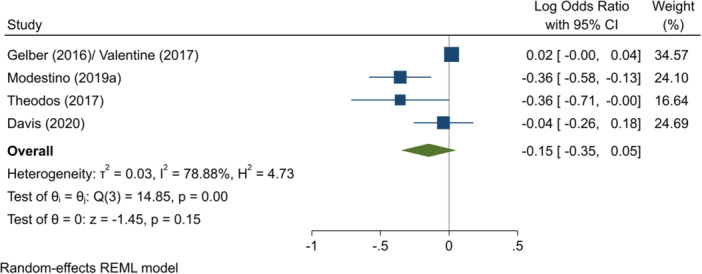

Entry to employment, full period (log OR)

-

∘

Summer employment programmes: −0.15 (−0.35, +0.05); no impact; I 2 = 78.88%; p = 0.00; low confidence.

-

∘

-

–

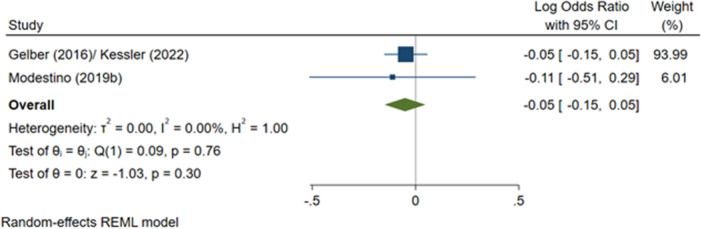

Likelihood of having a criminal justice outcome (log OR):

-

∘

Summer employment programmes: −0.05 (−0.15, +0.05); no impact; I 2 = 0.00%; p = 0.76; low confidence.

-

∘

-

–

Likelihood of having a drug‐related criminal justice outcome (log OR):

-

∘

Summer employment programmes: +0.16 (−0.57, +0.89); no impact; I 2 = 65.97%; p = 0.09; low confidence.

-

∘

-

–

Likelihood of having a violence‐related criminal justice outcome (log OR):

-

∘

Summer employment programmes: +0.03 (−0.02, +0.08); no impact; I 2 = 0.00%; p = 0.22; moderate confidence.

-

∘

-

–

Likelihood of having a property‐related criminal justice outcome (log OR):

-

∘

Summer employment programmes: +0.09 (−0.17, +0.34); no impact; I 2 = 45.01%; p = 0.18; low confidence.

-

∘

-

–

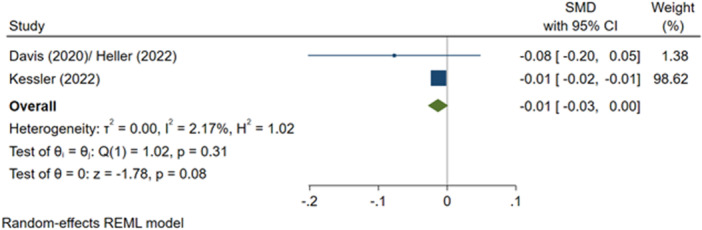

Number of criminal justice outcomes, during programme (SMD):

-

∘

Summer employment programmes: −0.01 (−0.03, +0.00); no impact; I 2 = 2.17%; p = 0.31; low confidence.

-

∘

-

–

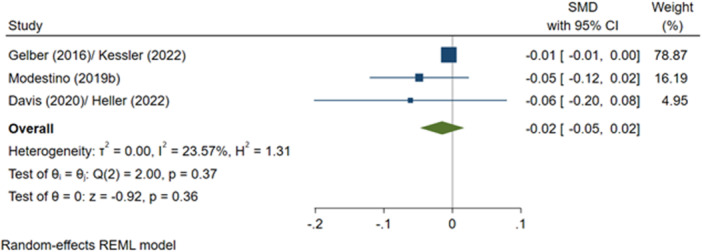

Number of criminal justice outcomes, post‐programme (SMD):

-

∘

Summer employment programmes: −0.01 (−0.03, +0.00); no impact; I 2 = 23.57%; p = 0.37; low confidence.

-

∘

-

–

Number of drug‐related criminal justice outcomes, post‐programme (SMD):

-

∘

Summer employment programmes: −0.01 (−0.06, +0.06); no impact; I 2 = 55.19%; p = 0.14; moderate confidence.

-

∘

-

–

Number of violence‐related criminal justice outcomes, post‐programme (SMD):

-

∘

Summer employment programmes: −0.02 (−0.08, +0.03); no impact; I 2 = 44.48%; p = 0.18; low confidence.

-

∘

-

–

Number of property‐related criminal justice outcomes, post‐programme (SMD):

-

∘

Summer employment programmes: −0.02 (−0.10, +0.05); no impact; I 2 = 64.93%; p = 0.09; low confidence.

-

∘

We re‐express instances of significant impact by programme type where we have moderate or high confidence in the security of findings by translating this to a form used by one of the studies, to aid understanding of the findings. Allocation to a summer education programme results in approximately 60% of individuals moving from never reading for fun to doing so once or twice a month (engagement in/participation in/enjoyment of education), and an increase in the English Grade Point Average of 0.08. Participation in a summer education programme results in an increase in overall Grade Point Average of 0.14 and increases the likelihood of completing higher education by 1.5 times. Signs are positive for the effectiveness of summer education programmes in achieving some of the education outcomes considered (particularly on test scores (when pooled across types), completion of higher education and STEM‐related higher education outcomes), but the evidence on which overall findings are based is often weak. Summer employment programmes appear to have a limited impact on employment outcomes, if anything, a negative impact on the likelihood of entering employment outside of employment related to the programme. The evidence base for impacts of summer employment programmes on young people's violence and offending type outcomes is currently limited – where impact is detected this largely results in substantial reductions in criminal justice outcomes, but the variation in findings across and within studies affects our ability to make any overarching assertions with confidence. In understanding the effectiveness of summer programmes, the order of outcomes also requires consideration – entries into education from a summer employment programme might be beneficial if this leads towards better quality employment in the future and a reduced propensity of criminal justice outcomes.

Qualitative Synthesis

Various shared features among different summer education programmes emerged from the review, allowing us to cluster specific types of these interventions which then aided the structuring of the thematic synthesis. The three distinct clusters for summer education programmes were: catch‐up programmes addressing attainment gaps, raising aspirations programmes inspiring young people to pursue the next stage of their education or career, and transition support programmes facilitating smooth transitions between educational levels. Depending on their aim, summer education programme tend to provide a combination of: additional instruction on core subjects (e.g., English, mathematics); academic classes including to enhance specialist subject knowledge (e.g., STEM‐related); homework help; coaching and mentoring; arts and recreation electives; and social and enrichment activities. Summer employment programmes provide paid work placements or subsidised jobs typically in entry‐level roles mostly in the third and public sectors, with some summer employment programmes also providing placements in the private sector. They usually include components of pre‐work training and employability skills, coaching and mentoring. There are a number of mechanisms which act as facilitators or barriers to engagement in summer programmes. These include tailoring the summer programme to each young person and individualised attention; the presence of well‐prepared staff who provide effective academic/workplace and socio‐emotional support; incentives of a monetary (e.g., stipends and wages) or non‐monetary (e.g., free transport and meals) nature; recruitment strategies, which are effective at identifying, targeting and engaging participants who can most benefit from the intervention; partnerships, with key actors who can help facilitate referrals and recruitment, such as schools, community action and workforce development agencies; format, including providing social activities and opportunities to support the formation of connections with peers; integration into the workplace, through pre‐placement engagement, such as through orientation days, pre‐work skills training, job fairs, and interactions with employers ahead of the beginning of the summer programme; and skill acquisition, such as improvements in social skills. In terms of the causal processes which lead from engagement in a summer programme to outcomes, these include: skill acquisition, including academic, social, emotional, and life skills; positive relationships with peers, including with older students as mentors in summer education programmes; personalised and positive relationships with staff; location, including accessibility and creating familiar environments; creating connections between the summer education programme and the students' learning at home to maintain continuity and reinforce learning; and providing purposeful and meaningful work through summer employment programmes (potentially facilitated through the provision of financial and/or non‐financial incentives), which makes participants more likely to see the importance of education in achieving their life goals and this leads to raised aspirations. It is important to note that no single element of a summer programme can be identified as generating the causal process for impact, and impact results rather from a combination of elements. Finally, we investigated strengths and weaknesses in summer programmes at both the design and implementation stages. In summer education programmes, design strengths include interactive and alternative learning modes; iterative and progressive content building; incorporating confidence building activities; careful lesson planning; and teacher support which is tailored to each student. Design weaknesses include insufficient funding or poor funding governance (e.g., delays to funding); limited reach of the target population; and inadequate allocation of teacher and pupil groups (i.e., misalignment between the education stage of the pupils and the content taught by staff). Implementation strengths include clear programme delivery guidance and good governance; high quality academic instruction; mentoring support; and strong partnerships. Implementation weaknesses include insufficient planning and lead in time; recruitment challenges; and variability in teaching quality. In summer employment programmes, design strengths include use of employer orientation materials and supervisor handbooks; careful consideration of programme staff roles; a wide range of job opportunities; and building a network of engaged employers. Design weaknesses are uncertainty over funding and budget agreements; variation in delivery and quality of training between providers; challenges in recruitment of employers; and caseload size and management. Implementation strengths include effective job matching; supportive relationships with supervisors; pre‐work training; and mitigating attrition (e.g., striving to increase take up of the intervention among the treatment group). Implementation weaknesses are insufficient monitors for the number of participants, and challenges around employer availability.

Keywords: crime and justice outcomes, disadvantaged youth, education, employment, meta‐analysis, summer programmes

1. PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Do summer education and employment programmes make a difference to young people who are disadvantaged or at risk of achieving poor outcomes, and if so, to what extent and how do they do this?

1.1. Key messages

-

▪

The evidence suggests that summer education programmes lead to an improvement in some education outcomes among the disadvantaged or ‘at risk’ young people involved.

-

▪

The evidence suggests that summer employment programmes have a limited or no impact on the employment or education outcomes of disadvantaged or ‘at risk’ young people, although there appears to be an impact on ‘softer’ outcomes, such as job readiness or socio‐emotional skills, which might lead to improvements in other outcomes over the longer‐term, and where impacts on violence and offending outcomes are identified these are substantial.

-

▪

There are issues with the quality of evidence that this review draws upon, which affects our confidence in the findings. Additionally, there are some types of outcomes, including violence and offending, health, and socio‐emotional, that are not studied as extensively as education or employment related outcomes. These need to be studied further to fully understand the impact summer programmes have.

1.2. What is a summer programme?

Summer programmes take place in the long vacation between academic years or after the final academic year and are additional to the usual curriculum. This review centres on two types of summer programme): summer education programmes which involve educational instruction; and summer employment programmes that include a fixed‐term job placement.

1.3. How might summer programmes benefit disadvantage or ‘at risk’ young people?

Summer programmes might improve the outcomes of disadvantaged or ‘at risk’ young people by:

-

▪

offering them provision that is alternative and extra to the usual curriculum for their age and stage;

-

▪

providing them with productive activities, such as coursework or an internship;

-

▪

distracting them from unproductive activities, such as antisocial behaviour or criminal activity;

-

▪

raising their aspirations to, for example, progress to higher education;

-

▪

supporting their transition from one education stage to another; and

-

▪

teaching them new hard and soft skills.

1.4. What did we want to find out?

We wanted to understand whether summer programmes lead to improvements for disadvantaged or ‘at risk’ young people on five different types of outcome, namely education, employment, violence and offending, health and socio‐emotional outcomes, and if so, how, by identifying key features of successful summer programmes that lead to these outcomes.

1.5. What did we do?

We searched for studies that examined the impact of summer programmes on the outcomes of disadvantaged young people, and other studies associated with these that examined what affected the impact the summer programme had. We also searched for the latter study type of summer programmes implemented in the UK, regardless of whether there was a study that examined the impact of the summer programme. We compared and summarised the results of the studies and rated our confidence in the evidence, based on factors such as study methods and sample sizes.

1.6. What did we find?

We found 68 studies that engaged between less than 100 to nearly 300,000 individuals in a summer programme. Forty‐one of these studies estimated the impact of the summer programme on the young person's outcomes.

We have some degree of confidence that summer education programmes appear to have had no impact on reading and mathematics test scores, although there are significant differences in this finding for mathematics test scores between the studies included. We have some degree of confidence that summer education programmes appear to have had a beneficial impact on: English and all forms of test scores (although there are significant differences in this finding for all forms of test scores between the studies included); the likelihood of completing higher education (although there are significant differences in this finding between the studies included); and STEM‐related higher education outcomes.

We have some degree of confidence that summer employment programmes appear to have had no impact on: mathematics, overall, and all forms of test scores; the likelihood of having negative behavioural outcomes at school such as a suspension (although there are significant differences in this finding for mathematics test scores between the studies included); and the likelihood of progressing to, or completing higher education (although there are significant differences in this finding for mathematics test scores between the studies included). Where summer education programmes appear to have had a beneficial or detrimental impact on outcomes, due to the evidence available we cannot be certain about the finding.

1.7. What are the limitations of the evidence?

Several outcomes, including violence and offending, health and socio‐emotional outcomes, are only evaluated by a small number of studies. Additionally, outcomes are generally only measured over a relatively short time period whereas data over a longer time period is needed to understand the longer‐term effects of summer programmes. Lastly, some aspects of the quality of the evidence are limited: studies estimating the impact of summer programmes often suffer from individuals allocated to participate in the summer programme not taking up their place, which could affect the reliability of the estimates of impact; studies evaluating how summer programmes affect young people's outcomes often only do so informally as part of a study estimating their impact.

1.8. How up to date is this evidence?

The evidence covers from 2012 up to the end of 2022.

2. BACKGROUND

Many intervention studies of summer programmes examine their impact on the outcome domains of employment (e.g., Alam et al., 2013; Valentine et al., 2017) and education (e.g., Leos‐Urbel, 2014; Schwartz et al., 2020). However, there is growing interest in the impact of participating in summer programmes on the reduction of anti‐social behaviour, including young people's violence and criminal activity. Evaluating a Boston‐based summer employment programme using a randomised controlled trial (RCT), Modestino (2019b) observed a reduction in violent‐crime and property‐crime arrests among programme participants – a pattern that persisted up to 17 months after participation. Furthermore, programme participants showed significant increases to community engagement, social skills, job readiness, and future intentions to work (Modestino & Paulsen, 2019a). This reduction in criminal behaviour was also observed in other summer employment programmes implemented in other cities across the United States (Davis & Heller, 2020; Heller, 2014, 2022). The initial evidence base on summer programmes offers some promise in terms of improving young people's outcomes and life chances. However, given the lack of a systematic review that estimates the extent of this, we cannot yet fully assert this. This current review seeks to fill this evidence gap.

In the body of available literature, there is no common definition of what constitutes a ‘summer programme’; most authors also do not propose a definition. However, there are some common groupings of summer programmes. There are numerous summer ‘education’ programmes – those that incorporate some form of academic instruction or support. Within this grouping there is significant heterogeneity in the type of intervention. Some summer education programmes are focused on ‘catch‐up’ for students who are falling behind their peers, for instance New York's Summer Success Academy (see Mariano & Martorell, 2013). Others aim to support young people through transitions between stages of education – bridge programmes for incoming college students are particularly common in the US (e.g., Barnett et al., 2012), while outreach programmes, commonly run by universities in the UK such as the Aimhigher West Midlands UniConnect programme (see Horton & Hilton, 2020), look to raise the aspirations of school leavers and encourage entry to higher education.

‘Employment’ summer programmes instead focus on transitions to the labour market, typically through some form of job placement often alongside wider employment support including careers guidance and skills development – examples include the Boston Summer Youth Employment Program (see Modestino & Paulsen, 2019a; Modestino, 2019b) and One Summer Chicago (see Davis & Heller, 2020; Heller, 2014, 2022).

While there is wide variation in the features of different types of summer programmes, the literature identifies some areas where there are commonalities within and across summer programme types, namely:

the period in which the programme is delivered;

the programme duration;

the type of organisation delivering the programme;

the programme's participants;

the types of tasks and activities included in the programme; and

the programme's target outcomes (primarily short‐term).

For the purposes of this review, the authors considered these features to construct operational definitions for different types of summer programmes.

2.1. Policy relevance

A preliminary literature review to scope evaluations of summer programmes identified that they may result in outcomes across the following domains:

education (e.g., school participation, school completion, academic attainment, school readiness);

employment (e.g., job readiness, soft skills, unemployment, job search skills);

violence and offending (e.g., likelihood of reoffending, likelihood of involvement in illegal activity);

socio‐emotional (e.g., resilience, confidence, social skills, community engagement, emotion management); and

health (e.g., understanding of health issues, such as substance abuse, physical activity, nutrition, and condition management).

This review is sponsored by Youth Endowment Fund (YEF, 2022) and Youth Futures Foundation (YFF). It is therefore anchored on the Outcomes Framework of YEF – which focuses on reducing offending among young people and takes account of the outcomes prioritised by YFF – which focus on supporting better employment for young people.

Given the early evidence showing reductions in criminal activity due to young people's participation in summer employment programmes (see Davis & Heller, 2020; Heller, 2014, 2022; Modestino & Paulsen, 2019a; Modestino, 2019b), a systematic review and meta‐analysis was an appropriate next step to be able to verify the positive impact observed in previous studies and to estimate the magnitude of this positive impact (if it is found to be present). However, we expanded the coverage of this systematic review to include summer education programmes (e.g., summer schools, summer learning programmes), as well as to look at a broader set of outcomes across the domains outlined above.

The rationale to do this is the inverse relationship between educational outcomes and violence among young people, which has been extensively documented (and is neatly summarised in Bushman et al., 2016). Given the currently mixed evidence regarding the effect of summer education programmes and summer work programmes on educational outcomes (see Barnett et al., 2012; Gonzalez Quiroz & Garza, 2018; Kallison & Stader, 2012; Lynch et al., 2021; Sablan, 2014; Terzian et al., 2009), this review presents an opportunity to examine their impact – though indirect – on violence among young people. Education and employment are linked and interact in deterring the production of antisocial behaviour (Lochner, 2004), a relationship acknowledged by the Outcomes Frameworks of both YEF and YFF; the expert reference group for the development of YEF's Outcomes Framework acknowledged that engagement in education is one of the most important factors in protecting young people from crime and violence. Further, young people who become involved in the youth justice system are also disproportionately likely to have mental health problems including anxiety and depression, and there is clear evidence of the links between work and health and socio‐emotional wellbeing (Waddell & Burton, 2006), and education and health and socio‐emotional wellbeing (Brooks, 2014; Department of Health, 2008). In light of this interrelatedness, considering education and employment‐oriented summer programmes in this systematic review, and considering their effects across a wide range of highly interrelated outcome domains through direct, moderated and indirect effects is pertinent. It is also consistent with contemporary theories of the development of young people (Lerner & Castellino, 2002; YFF, 2021).

Disadvantaged young people are those who are at risk of poorer outcomes, including educational, economic, health, and social outcomes, as a result of one or more adverse situational and behavioural factors faced in childhood and/or the transition to adulthood. Situational factors that increase risks include race and ethnicity, low socioeconomic status, low parental attainment, being in care or being a care giver, and/or having disabilities or health conditions including mental health conditions. Behavioural factors that increase risk include involvement in crime or anti‐social behaviour, a low level or lack of parental support, truanting and being excluded from school, teenage pregnancy and poor school performance in early years (Kritikos & Ching, 2005; Machin, 2006; Pring et al., 2009; Rathbone/Nuffield Foundation, 2008).

Summer ‘education’ and ‘employment’ summer programmes warrant considering together within this review as the contexts of and mechanisms employed by these programmes are often similar, and while there may be differences in the proximal outcomes they typically aim to achieve (summer education programmes are typically focused on educational attainment, and have successful completion of and transitions between stages as their primary outcomes while summer employment programmes are typically focused on entry to employment and labour market outcomes), as discussed these outcomes are highly interrelated, with programmes having a range of indirect effects on participants. Additionally, any variation in the outcomes typically achieved by different summer programme types is important for policymakers to be aware of.

2.2. How the intervention might work

2.2.1. Rationale for delivery and key assumptions

Summer programmes aim to improve the outcomes of young people through offering them alternative and extra provision; that is, additional to the usual curriculum for their age and stage (which may be considered ‘service as usual’) (Barnett et al., 2012; EEF, n.d.; Heller, 2022; Hutchinson et al., 2001; Modestino, 2019b; Tarling & Adams, 2012). The intention is to avoid interference with the standard curriculum and to build additional support to improve outcomes in ‘service as usual’ including progression through education as well as into the labour market. An assumption is that targeted young people will find programmes attractive and engage in them, with a further assumption that they will be supported by their families and/or carers to do so.

While the characteristics of the target group may vary – from those with offending histories or at risk of these (Modestino, 2019b; Tarling & Adams, 2012), to those with low attendance and low attainment (Hutchinson et al., 2001) and to what is sometimes described as the grey or middle group who fail to grab attention but also are at risk of poorer outcomes due to not having firm ambitions (Barnett et al., 2012) – there is also recognition that the selected target group is not engaging with ‘service as usual’ as effectively as other groups, or not engaging at all. Therefore, the assumption is that an alternative approach is required to foster more positive engagement or re‐engagement to achieve outcomes.

Summer education programmes may focus on ‘catch up’ with aims of closing the attainment gap for disadvantaged learners (EEF, n.d.; Tarling & Adams, 2012) or be aimed to support transitions between education phases (Hutchinson et al., 2001) and to accelerate achievement in the next education phase (Barnett et al., 2012). They may offer learning in an alternative format (Tarling & Adams, 2012), as part of smaller groups or with more staff support which can lead towards better attainment (EEF, n.d.). The underlying assumption, as identified by the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) toolkit (n.d.), is simply that more time in school/education leads to better educational outcomes.

Summer employment programmes may share similar aims. For example, Alam et al. (2013) explore summer employment programmes that aim to support and improve transitions to the next stage of education. The assumption is that the job placement creates an early insight into the labour market that builds ambition. This, in turn, increases understanding of the importance of educational credentials to good quality work. As a result, motivation for achieving in the next phase of education is increased. Summer employment programmes may also aim to divert or distract those who have been involved in or are at risk of offending away from harmful or unproductive activities (Leos‐Urbel, 2014; Modestino, 2019b). The underlying assumption is that through providing alternative uses for the time over summer that otherwise would be unallocated, this reduces the risk of that time being used for criminal or anti‐social activity.

2.2.2. Mechanisms

There are a number of mechanisms through which summer programmes work, with many of these shared across job and education programmes. This stems in large part from common intermediate outcomes relating to personal and social development, and vocational and applied skill acquisition. For example, Modestino (2019b) identifies a mechanism through building aspiration, self‐belief, emotion control and a longer‐term work ambition. The summer employment programme encourages young people to improve their engagement with education as a precursor to achieving newly found higher quality employment goals. This, in turn, leads to better attainment – which was an outcome not originally anticipated. The commonalities with the summer education programme concern the soft skill development including self‐esteem and confidence, emotion control, leadership skills, communication, problem‐solving, and responsibility and time management (Hutchinson et al., 2001; Leos‐Urbel, 2014).

A common mechanism in the summer programmes targeted at disadvantaged or ‘at risk’ young people is the opportunity to form better relationships. In summer education programmes, this can result from the group of young people formed for the programme (EEF, n.d.; Hutchinson et al., 2001). It also results where delivery teams are new to the young people. Hence, in summer education programmes that are delivered by staff who are different from those in ‘service as usual’, there is a chance to re‐set engagement with adults, which can then set the tone for the next stage of ‘service as usual’. In summer employment programmes, the adult relationship is formed with employees in the employing organisation. This, along with the employers' expectation of performance from the young person, builds responsibility, maturity and self‐esteem (Alam et al., 2013; Modestino, 2019b). Improved interpersonal relationships might also contribute towards feeling more settled thereby supporting improved wellbeing – although evidence for these outcomes is weak (Terzian et al., 2009).

In both summer employment and summer education programmes, financial incentives can be a mechanism for change (Barnett et al., 2012; Modestino, 2019b). Providing financial recognition can have an important effect on how the opportunity is valued within the young person's household – which can support engagement from families and/or carers, as well as providing a reward for the young person's time. Financial incentives may also help to alleviate financial constraints on future education, increasing investment in human capital and improving longer‐term outcomes.

Location is an important mechanism to the outcomes for some summer programmes. For summer employment programmes, young people are exposed to the world of work, and are located in an organisation for a job placement. This builds familiarity and confidence in this new setting as well as increasing expectations for conduct in an adult environment (Heller, 2022; Modestino, 2019b). Where summer education programmes support transitions to the next phase of education they may take place on the campus of that next phase. This similarly builds familiarity and confidence to be in this new environment. In these programmes, building familiarity with the campus and the services available can increase likelihood to seek out and use support services post‐transition, which provides crucial underpinning to sustaining this destination that is, reducing the likelihood of drop‐out, particularly important when transitioning to higher education. Finally, summer education programmes may be located in alternative settings, such as the outdoors, providing a different context for learning that can support young people to engage differently and to achieve, thereby building confidence for learning in the traditional classroom setting (Tarling & Adams, 2012; Terzian et al., 2009).

These are all positive causal mechanisms to the achievement of outcomes; however, some studies identify the potential for negative effects from summer programme participation resulting from some of these mechanisms. This includes, for example, Alam et al. (2013) who suggest that requiring disadvantaged young people to attend summer employment programmes at a time when their peers are at rest and on vacation can leave them exhausted and not well placed for the start of the new term. This is a risk that intuitively reads across to summer education programmes. Consequently, duration and intensity of the programmes are important contextual factors in the analysis. Alam et al. (2013) also indicate that the positive effect on attainment established by Modestino (2019b) may not result from all summer employment programmes. Rather than build motivation through understanding why education is important, the ability to earn ‘easy’ money from summer jobs may deter young people from engaging in their further studies. Quality of and safeguarding in the job placement are also a key consideration to ensure young people do not see negative consequences, such as from encountering poor social behaviour among permanent or standard employees. For economically disadvantaged young people, a further negative consequence of being part of summer employment or education programmes may be that they are unavailable for activities such as standard employment that is better paid. This may have consequences for short‐ and long‐term financial returns as well as for engagement and attrition in programmes.

2.2.3. Outcomes

Considering the mechanisms through which summer programmes may affect positive outcomes over the longer‐term, summer employment programmes provide meaningful employment experiences which can provide alternative pathways for disadvantaged young people, opening up economic opportunities to them which, because of their disadvantage, may be limited outside of public interventions, relative to more advantaged young people (Modestino & Paulsen, 2019a). Summer education programmes, through the mechanisms discussed above, may lead to improved academic attainment in ensuing phases of education, which also improve future economic opportunities by increasing the individuals' skills and desirability in the labour market. As a result, both summer education and summer employment programmes can improve violence and offending outcomes – by improving the individuals' economic opportunities. This can set expectations about their future quality of life, and mean they are less likely to offend as the opportunity costs of the punishment are increased (Heller, 2014).

Wider evidence supports these causal pathways. For example, Bell et al. (2018) demonstrates the links between improved education attainment and prolonged education on criminal justice outcomes, citing research by Lochner (2004). Additionally, statistics from the UK Department for Education demonstrate the links between higher levels of education and higher skilled employment, comparing graduates and postgraduates with non‐graduate outcomes, as well as the higher propensity to be employed rather than economically inactive by the higher level of qualification attained. Further evidence is supplied by the OECD (2020) that sets out the higher likelihood of being employed by the higher level of education. In this way, education outcomes can be seen as intermediaries in the path to better employment outcomes, and better offending outcomes.

Improved economic opportunities resulting from participation in a summer programme may also affect positive health and socio‐emotional outcomes, by potentially improving nutritional choices, reducing anxiety and stress, and increasing self‐confidence and self‐worth as a result of increased financial resources. Given the interrelatedness between education, employment, violence and offending, health and socio‐emotional outcomes, intermediate improvements in outcomes within one domain, as a direct result of participation in a summer education or employment programme, is likely to result in improved outcomes across the other domains.

The points raised in this background section are not intended to be comprehensive – further assumptions, mechanisms and outcomes are likely to be identified as the literature is systematically searched.

3. RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

3.1. Research questions

Based on the findings of the preliminary literature review covering types of summer programmes, their outcomes, and the goals of the funding organisations, this review aims to answer the following research questions:

3.1.1. Meta‐analysis

-

1.

To what extent does participation in summer employment programmes:

-

a.

improve violence and offending outcomes?

-

b.

improve educational outcomes?

-

c.

improve employment outcomes?

-

d.

improve socio‐emotional outcomes?

-

e.

improve health outcomes?

-

a.

-

2.

To what extent does participation in summer education programmes:

-

a.

improve violence and offending outcomes?

-

b.

improve educational outcomes?

-

c.

improve employment outcomes?

-

d.

improve socio‐emotional outcomes?

-

e.

improve health outcomes?

-

a.

-

3.

To what extent do the outcomes achieved by summer programmes vary based on the study, participant and intervention characteristics including the racial and ethnic make‐up of participants?

3.1.2. Thematic synthesis

-

4.

What are common features of summer employment and education programmes that produce positive outcomes? Which features contribute most to the achievement of:

-

a.

improved violence and offending outcomes?

-

b.

improved educational outcomes?

-

c.

improved employment outcomes?

-

d.

improved socio‐emotional outcomes?

-

e.

improved health outcomes?

-

a.

-

5.

In which contexts are summer employment and education programmes most or least able to produce positive outcomes? Are any contexts more or less able to produce:

-

a.

improved violence and offending outcomes?

-

b.

improved educational outcomes?

-

c.

improved employment outcomes?

-

d.

improved socio‐emotional outcomes?

-

e.

improved health outcomes?

-

a.

-

6.

Which mechanisms inhibit or enable the effectiveness of summer employment and education programmes? Are any mechanisms particularly important to achieving:

-

a.

improved violence and offending outcomes?

-

b.

improved educational outcomes?

-

c.

improved employment outcomes?

-

d.

improved socio‐emotional outcomes?

-

e.

improved health outcomes?

-

a.

-

7.

In what ways do factors such as targeting, retention, and dropout affect the achievement of outcomes by summer employment and education programmes?

Additionally, data on the cost of delivering summer programmes, where reported on, is also to be synthesised.

3.1.3. Why is this review needed in light of existing reviews?

While still limited, the evidence base for the impact of summer programmes is growing. There have been a number of intervention studies that examine the effect of summer employment programmes on antisocial behaviour among young people (e.g., Davis & Heller, 2020; Heller, 2014, 2022; Modestino & Paulsen, 2019a; Modestino, 2019b). Findings from these individual intervention studies are promising, showing a relationship between participation in summer employment programmes and reduced antisocial behaviour. However, the lack of a systematic review makes it difficult to assert this relationship exists and to estimate the extent to which positive behavioural outcomes can be attributed to participation in the programmes. This review examines the impact of summer employment programmes on other outcomes that influence young people's life chances, such as education and employment – both outcome domains that at least some of the evidence on summer employment programmes has examined – as well as violence and offending, socio‐emotional and health outcomes.

There is a well‐documented link between educational outcomes and violence among young people (Bushman et al., 2016), so it is also important to take stock of these summer programmes. EEF sponsored a systematic review of summer schools and their impact on educational outcomes among 3‐to‐18‐year‐olds for their Teaching and Learning Toolkit (EEF, n.d.). This found that summer schools have a moderate impact on educational outcomes. Other evidence of the positive impact of summer schools is also conclusive (see Cooper et al., 2000; Lauer et al., 2006). However, evaluations of other forms of education‐oriented summer programmes have yielded more mixed results (see Barnett et al., 2012; Gonzalez Quiroz & Garza, 2018; Kallison & Stader, 2012; Lynch et al., 2021; Terzian et al., 2009). The inclusion of literature on education‐oriented summer programmes offers an opportunity to clarify the currently mixed evidence regarding their impact. There is also a need to update the existing evidence in light of policy changes, such as the transition to and implementation of the Raised Participation Age (RPA) policy in England in 2012; of the 59 studies included in the EEF systematic review, only five were published since 2012, with the most recent published in 2014. Additionally, summer education programmes may affect outcomes across domains other than education, which warrants investigation. Furthermore, given the age range employed by EEF, summer schools, which constitute a large component of summer education programmes, have not been synthesised for their effects beyond the age of 18. This means current analyses do not cover any studies focused on post‐18 study which may be compensatory (catching up on what should have been achieved in compulsory schooling) or at the further or higher level.

To support the Wallace Foundation's Summer Learning Toolkit, RAND have also performed a systematic review of summer programmes, covering programmes focused on education and employment as well as wellbeing and enrichment (McCombs et al., 2019; Wallace Foundation, n.d.). The review covered only interventions from the US, and across age groups from pre‐kindergarten through to the summer before grade 12 (ages 17–18). Outcomes relating to academic achievement, academic and career attainment, engagement with schooling, social and emotional competencies, physical and mental health, and the avoidance of risky behaviour were considered, although no meta‐analyses were conducted. Similarly, the Transforming Access and Student Outcomes in Higher Education centre (TASO) has a stream relating to summer schools in their Evidence toolkit. It is based on a collection of UK interventions centred on transitions to higher education (TASO, n.d.), which finds that summer schools have a positive impact on student aspirations and attitudes. The strength of evidence is noted as ‘emerging’, that is, relatively weak, with many of the studies covered not employing robust experimental/quasi‐experimental designs.

4. OVERVIEW OF APPROACH

The protocol for this review (Muir et al., 2023) outlined the review's intended approach. A section below details all the deviations from this.

This systematic review and meta‐analysis are underpinned by four key stages:

-

1.

Searching the appropriate literature through an agreed list of search terms.

-

2.

Selecting relevant studies based on specified and agreed inclusion and exclusion criteria.

-

3.

Extracting relevant evidence using an agreed protocol.

-

4.

Synthesising and interpreting the evidence to inform high quality, user friendly, accessible, engaging, relevant and useful reviews.

This systematic review has examined out‐of‐school‐time programmes conducted throughout or at some point during the summer months (i.e., the period in which the long vacation takes place between academic years or after the final academic year before moving into economic activity). These programmes include summer employment programmes and summer education programmes.

The focus is how these programmes improve outcomes among young people who are disadvantaged and/or at risk of poorer outcomes in later life (‘at risk’), including educational, economic, health, and social outcomes, as a result of one or more adverse situational and behavioural factors faced in childhood or as a young adult. While the experience of even one disadvantage factor may lead to young people facing difficulties in transitioning into adulthood, disadvantage factors often interact and compound each other leading to severe adverse impacts for young people and society, including decreased productivity and the perpetuation of poverty and social exclusion. On this, a pertinent example is that disadvantaged young people are twice as likely to be long‐term NEET (Not in Education, Employment or Training) as their better off peers (Gadsby, 2019)

As is standard with systematic reviews, content experts were consulted with to refine the search terms and define the list of databases to search. For this study, the content experts were drawn from the review advisory group.

To determine whether summer programmes produce improvements in outcomes of interest, and to estimate the magnitude of this relationship (where it exists) (see research questions 1 through 3), meta‐analyses have been conducted (where possible), employing the random effects model.

Since this systematic review also sought to identify components and features shared across successful summer programmes (see research questions 4 through 7), qualitative evaluations of the interventions shortlisted for meta‐analyses were examined to understand the causal pathway to outcomes. This was expanded by examples found in the UK where these met the inclusion criteria for the review, except for study design. This approach, recommended by the expert panel, sought to enable the review to tap into the UK context, particularly for implementation data. Where outcomes of interest were not observed or covered by these studies, these interventions do not feed into the analysis of the causal pathway.

5. SEARCH STRATEGY

Various electronic databases were systematically searched to identify studies for inclusion in the review:

Key databases including Scopus, PsycInfo, Child Development and Adolescent Studies (CDAS), the Education Resources Information Centre (ERIC), and the British Education Index (BEI).

Wider resources including the current unpublished updated YFF EGM, which includes studies from the 3ie Evidence and Gap Map/Kluve synthesis, the summer school streams of EEF's Teaching and Learning Toolkit and TASO's Evidence toolkit, and RAND's summer programmes evidence review (McCombs et al., 2019) that supports the Wallace Foundation's Summer Learning Toolkit.

The Pathways to Work Evidence Clearinghouse, Clearinghouse for Labour Evaluation and Research; Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation (OPRE), Administration for Children and Families; MDRC; the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER); and the Trip database.

The most relevant journals – the Journal of Youth Studies, Youth & Society, International Journal of Adolescence and Youth (IJAY), Journal of Social Policy, and Youth.

Sources of grey literature – Google Scholar, gov.uk, gov.scot, wales.gov.uk, northernireland.gov.uk, gov.ie, National Lottery Community Fund, Care Leavers Association, Children's and Young People's Centre for Justice, Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF), Centre on the Dynamics of Ethnicity, Nuffield Foundation, Regional Studies Association (RSA), Centrepoint, Youth Employment UK, Impetus, Edge, Education and Employers, National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER), the Sutton Trust, and TASO.

Several other databases that might be expected to be included in this list were not, as during piloting and testing of the search string, these additional databases surfaced limited/no additional studies of relevance. These additional databases cover Medline, the World Health Organization's International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, databases in the US National Library of Medicine including ClinicalTrials.gov, Social Care Online from SCIE, Epistemonikos, the libraries of Cochrane and the Campbell Collaboration, additional What Works Centres including the What Works Wellbeing, the Wales Centre for Public Policy and the What Works Centre for Children's Social Care.

Scopus is available through Elsevier, PsycInfo is available through the American Psychological Association; CDAS and BEI are available through EBSCO; the Journal of Youth Studies and the International Journal of Adolescence and Youth are available through Taylor & Francis Online; and the Journal of Social Policy is available through Cambridge Uni Press. In implementing the search strategy, the template and guidance provided by the Campbell Collaboration was followed (Kugley et al., 2017).

We used the following basic string to interrogate the identified databases:

(‘summer school*’ OR ‘summer learn*’ OR ‘summer education*’ OR ‘educational summer’ OR ‘summer bridge’ OR ‘summer employ*’ OR ‘summer work’ OR ‘summer place*’ OR ‘summer job*’ OR ‘summer apprentice*’ OR ‘summer intern*’ OR ‘summer camp*’ OR ‘summer program*’) AND (‘youth’ OR ‘young’ OR ‘child*’ OR ‘student*’ OR ‘pupil*’ OR ‘teenage*’ OR ‘adolescen*’ OR ‘juvenile’) AND (‘disadvantage*’ OR ‘vulnerab*’ OR ‘at risk’ OR ‘at‐risk’ OR ‘marginalised’ OR ‘marginalized’ OR ‘youth offend*’ OR ‘young offend*’ OR ‘delinquent’ OR ‘anti‐social’)

This string was developed through initial piloting and discussions with the review's advisory group. We used the full‐search string where possible. Where databases limit the length of the search string that can be used (either through physical limits or where the search function is too sensitive so that inputting the full search string is inappropriate), a hierarchical approach was employed, inputting as many of the key terms (ordered in terms of relevance) as possible, starting with those relating to the intervention before adding those relating to the population of interest (firstly age‐related, secondly disadvantage‐related). Depending on the size of the database and its subject‐matter focus, where a full advanced search was not possible searches centred on ‘summer’ or used individual searches for each of the terms relating to the programmes of interest that is, ‘summer school’ then ‘summer learn’ through to ‘summer program’. All fields of each record within each database were searched unless the number of hits was excessive and the relevancy of hits was too low. In these instances, searches were conducted within the abstract, title and/or key words.

The terms relating to the intervention type and the age/demographic group of participants were the predominant terms used in the literature. During piloting, a series of terms were tested relating to the disadvantage characteristics for the population of interest to identify whether these captured all of the literature of interest – some studies for instance might use specific disadvantage terms such as ‘poverty’ or ‘ethnic minority’ or ‘special educational needs’, raising a risk that they would not getting picked up by the search string. In each of the databases where it was possible to input the full search string, the piloting tested using 40 different search terms relating to specific forms of disadvantage. These additional searches yielded 1229 additional hits compared to the original shorter search string – of these, only six merited full text screening.

Where databases permitted, date limiters were applied to include studies published since January 1st, 2012, that is, approximately the last decade's research and covering the transition to and implementation of the Raised Participation Age (RPA) policy in England which affects education and training participation, and up to December 31st, 2022. This maximised the policy relevance of this review's findings. Only studies written in the English language were included; this is common practice across systematic reviews (Jackson & Kuriyama, 2019) despite potentially introducing bias to the review, although it has been shown that excluding non‐English language studies does not affect the main findings from meta‐analyses (Morrison et al., 2012). Additionally, the focus of the review on high income countries should also alleviate this as an issue, as studies based on interventions in high income countries may be more likely to be available in English, either primarily or as an alternative to the main non‐English language version. Furthermore, the saturation principle (discussed further in relation to the study design inclusion criteria) provides further support for this.

Searching Scopus surfaced relevant conference proceedings. Dissertations were included in the review where these were surfaced through the process detailed above, but no dissertation‐specific databases were searched. The references of the most relevant evidence reviews were searched thoroughly, namely the EEF and TASO toolkits and RAND's summer programmes evidence review (McCombs et al., 2019), as well as those of any additional systematic reviews surfaced through the search process.

We used ‘pearling’ (searching the citations of published evidence) to establish whether process studies were available for impact studies selected for the review, as well as to surface process studies related to UK interventions that were eligible for inclusion other than on study design (these are not included in the meta‐analyses or in the analysis of the causal pathway).

Where studies have an online appendix, these were also sourced manually and included alongside the main text if applicable.

The specific search string and details of the search process for each of the databases interrogated can be found in Supporting Information: Appendix 1.

6. STUDY ELIGIBILITY

6.1. Selection criteria

The following PICOSS criteria underpinned study selection.

6.1.1. Population

The population of interest was individuals aged 10–25 years (where necessary, judgements were based on whether students typically turned this age in the academic year of study). The upper end of this range covers the age at which the vast majority of individuals in the UK will have exited education and entered economic activity as well as corresponding to the upper end of the age range of interest to YFF. The lower end covers the transition from primary to secondary education in the UK as well as the lower end of the age range of interest to YEF. Where the age range of the participants in a study spanned the eligibility boundary/ies, the study was included where the majority of the sample met the inclusion criteria, or if the impact of the programme for those meeting the inclusion criteria could be separated from those that did not.

The young people taking part in summer schools also had to be considered as disadvantaged or at risk of poorer outcomes. These terms are used widely throughout the literature despite not being strictly defined. The review was not bounded by a concrete definition of characteristics of disadvantage or that might make an individual at risk of poorer outcomes, rather, this was determined by the descriptions given in the sources material. All groups who face disadvantage or are at risk of poorer outcomes across the domains of interest compared to the wider population were included, such as (but not be limited to), racial and ethnic minorities, individuals of low socioeconomic status, individuals who have experienced care, students with Special Educational Needs, individuals with health conditions or disabilities, as well as those who have already offended or have experience of the criminal justice system, and those who are already experiencing poorer outcomes including poor academic performance or those truanting or being excluded from school. Where both disadvantaged and non‐disadvantaged individuals were included in any study population, the study was included where the majority of individuals met the inclusion criteria, or if the impact of the programme for those that met the inclusion criteria could be separated from those that did not.

6.1.2. Intervention

As previously noted, the review centres on two main types of summer programme, which were surfaced by the preliminary literature review. These are summer employment and summer education programmes. For the purposes of this review, these programme types were operationally defined as follows:

-

▪

Summer employment programme: an out‐of‐school‐time programme that takes place during the summer months in whole or in part and includes a fixed‐term job placement.

-

▪

Summer education programme: an out‐of‐school‐time programme that takes place during the summer months in whole or in part, where content is majority administered through education‐focused instruction.

The summer months refer to the period in which the long vacation takes place between academic years or after the final academic year before moving into economic activity (referring to the employed, unemployed, and economically inactive populations above working age). Interventions that take place during the summer but are targeted at individuals who have already transitioned into economic activity were not of interest. Summer programmes that were a part of a wider intervention, for instance, including term‐time provision, were eligible for inclusion although the features, mechanisms and/or outcomes of the summer programme should be able to be separated out from the other components of the intervention, and/or the summer programme should constitute a substantial enough component of the whole for it to be reasonable to include. This was determined on a case‐by‐case basis – the reasoning behind decisions for any marginal cases are made transparent.

As part of the peer review process, we were challenged on the decision to exclude one cohort participating in the summer employment programme evaluated by Davis and Heller (2020) based on the population being ineligible. The individuals in what is described as the 2013 cohort in the study (note that the 2012 cohort was eligible for inclusion in the review) were aged 16–22 and approximately 41% came directly from the criminal justice system, and 59% came from high‐violence neighbourhoods. Both groups were deemed ineligible for inclusion based on the combination of their age and lack of requirement to be in education. The latter meant that the intervention would take place in a non‐transitional summer for these individuals.

The exclusion of the former group raises an issue as to how our population and intervention criteria interact. Individuals currently or previously involved in the criminal justice system are of significant interest to this review, but those entering a summer programme directly from the criminal justice system would not be ‘between academic years’. Studies are eligible for inclusion where the population comes from the criminal justice system at an age where, were they not involved in the criminal justice system, they would theoretically be in compulsory education or required to participate in education or training. For those young people that are in the criminal justice system and that, were they not, would be in economic activity instead, there is no need for the education/employment intervention they participate in to occur during the summer period as there is no reason for their transition out of the criminal justice system to be synchronised with the academic calendar (i.e., the summer period between academic years or after the final academic year which we are focused on). As such, theoretically for this population all education/employment interventions that occur in the period when they are transitioning from the community justice system back into the community could be included, but the review would lose its focus on summer programmes. Therefore, we stand behind our decision to exclude the cohort from Davis and Heller (2020) that in part comes directly from the criminal justice system.

This issue plays a role in determining the eligibility of only one other study surfaced by the review (in all other instances, another eligibility criteria results in the study's exclusion). Tarling and Adams (2012) evaluates the Summer Arts Colleges programme which targets at risk young people in England and Wales, including those leaving the criminal justice system. While the age range of the participant population was 12–19, the vast majority of participants were 15–17 and the average age was 16.4 years. Therefore, this study is included in the review, as for the vast majority of participants their involvement in the criminal justice system is at the expense of compulsory education, and therefore the intervention for them occurs during the summer months between what would be academic years, or after what would be their final academic year before moving into economic activity.

Sports programmes (which according to a broader definition could be considered education programmes) that were subjected to the systematic review of Malhotra et al. (2021) were not included. The definition of these sports programmes did not overlap with the interventions of interest to us – however interventions that met the definition of summer employment or summer education programmes which also featured sports activities were eligible for inclusion. Programmes of educational instruction that did not serve academic purpose, for instance cycle training programmes, were not considered – programmes where the educational instruction related to understanding of/familiarisation with transitions such as to higher education, were eligible as these employed various mechanisms of interest and in the broader sense constituted a summer education and not enrichment programme. Residential programmes which aimed to achieve this through familiarising students with a new environment were considered, provided that there was some taught element and the programme was not solely focused on enrichment activities. Programmes such as reading challenges or book gifting programmes without guided instruction were also not considered.

These definitions made the programme types mutually exclusive, and studies that evaluated a summer employment or summer education programme were included.

Interventions for inclusion should have been targeted at the population groups identified above. Universal interventions where young people that are disadvantaged or at risk of poorer outcomes fall into the intervention population but were not specifically targeted were not considered. The interventions should also have been provided directly to the population of interest, as opposed to indirectly through a third party such as their parents or teachers.

6.1.3. Comparison group

Primary studies were included in the systematic review where they drew on a comparison group (QED) or control group (RCT). The comparison group were young people who do not participate in summer programmes covered by the evaluation but who are similar to those who do participate. Typically, primary studies would draw comparison with groups of young people experiencing business as usual (BAU). Being able to access comparative analysis between intervention strands within primary evaluation reports was crucial for studies to be included. This requirement was dropped for studies evaluating UK‐based interventions which meet all the criteria for inclusion except for study design. These latter studies were only included in the analysis covering implementation and were not included in the meta‐analyses or in the analysis of the causal pathway, unless a relevant outcome was observed.

6.1.4. Outcomes

The review examined the impact of different types of summer programmes across the five outcome domains of interest: (1) violence and offending; (2) education; (3) employment; (4) socio‐emotional; and (5) health (where these are included alongside other outcomes of interest). To be included, a study must have evaluated the intervention according to an outcome within at least one of these domains, with those studies considering health outcomes included only where outcomes within another domain were also covered. This was to avoid ‘weight loss camps’ or programmes solely at helping young people to manage health conditions/disabilities from inclusion. Where these health interventions only looked to affect socio‐emotional outcomes which can be thought of as direct consequences of potential health outcomes, as opposed to distinctly separate outcomes (for instance, weight loss camps may also consider impacts on confidence and self‐esteem), then these were also not considered. Within the context of this systematic review, violence and offending also includes anti‐social behaviour.

The preliminary literature review identified that the outcomes measured as part of the evaluation of relevant interventions were mostly relatively short term, with studies often not following‐up after programme end. As such, outcomes that would usually be considered as intermediate, such as the acquisition of skills and attributes outlined in YEF's Outcomes Framework, were also considered as outcomes of interest to this review.

The specific outcomes that are of interest were guided by the Outcomes Framework of YEF and the outcomes of interest to YFF, as well as the preliminary literature review to scope existing evaluations of summer programmes. These include:

-

▪

Violence and offending – reduced offending and reoffending; reduced likelihood of carrying weapons. Both the severity and intensity of violent and offending behaviour were appropriately considered, as was the differentiation between self‐reported measures and measures based on recording from the police and/or criminal justice system.

-

▪

Educational – education and qualification completion (including performance and attainment in courses/exams); access to/in education (including application, participation, and completion in courses); education quality; technical skills & vocational training; improved study skills and academic mindset; improved critical and analytical skills.

-

▪

Employment – employment status; whether actively seeking employment; employment expectation; whether found appropriate employment; hours worked; job quality; earnings & salary; development of work appropriate ‘soft‐skills’ including job‐search skills.

-

▪

Socio‐emotional – resilience and persistence; increased confidence; improved behavioural adjustment indicators; improved social skills; community engagement; ability to manage emotions and resolve conflicts.

-

▪

Health – better understanding of health issues including substance use, physical activity, and nutrition; improved family well‐being; improved access to health‐related support services.

Where relevant, outcomes from longitudinal analyses are differentiated from those from correlational or cross‐sectional analyses. This can be seen explicitly as part of the thematic synthesis as these outcomes are more naturally differentiated in the meta‐analysis.

6.1.5. Study design

Experimental (RCT) and quasi‐experimental designs (QEDs) (including but not limited to regression discontinuity designs (RDDs), difference in differences (DIDs) and matching approaches) as part of evaluation studies with a robust and credible comparison group were included. Study designs that do not include a parallel cohort that establishes or adjusts for baseline equivalence are not considered to employ a robust and credible comparison group. These invalid designs could include single group pre‐post designs; control group designs without matching in time and establishing baseline equivalence; cross‐sectional designs; non‐controlled observational (cohort) designs; case‐control designs; and case studies/series.

Empirical studies looking at the implementation of an approach or process evaluations were included in the review to examine implementation questions – these were sourced from the pearling the citations of included counterfactual impact evaluations. Qualitative evaluations of this latter type of UK‐based interventions where these meet the inclusion criteria except for study design were also included.

To include qualitative evaluations in the thematic synthesis where we consider how the contexts of summer programmes affect the outcomes achieved through various mechanisms, a credible indication of what impacts the intervention achieved was necessary. Therefore, we required qualitative studies to be linked to a robust impact evaluation. Nonetheless, as this review is most interested in policies in the UK where there has until recently, with the development of the What Works movement, been a lack of tradition for robust impact evaluation, this requirement was suspended in this context.