Introduction

Excessive menstrual loss, or menorrhagia, is a significant healthcare problem in the developed world (box B1). In the United Kingdom, 5% of women of reproductive age will seek help for this symptom annually1; by the end of reproductive life the risk of hysterectomy (primarily for menstrual disorders) is 20%.2 This is also the situation in New Zealand.3 Objectively, menorrhagia is defined as a menstrual loss of 80 ml per month. Population studies have shown that this amount of loss is present in 10% of the population4 yet nearly a third of all women consider their menstruation to be excessive.5 This symptom thus creates a significant workload for health services.

Box 1.

: Indications for referral to a gynaecologist or for surgical management

- Age over 40

- Persistent intermenstrual bleeding

- Failed medical treatment

- Other factors—for example, abnormal smear, associated severe dysmenorrhoea

In clinical medicine the paradigm of evidence based medicine currently holds sway. Evidence based medicine implies not only the application of effective treatments but their rational use within a rational overall management framework. In the management of excessive menstrual loss there is good evidence that many doctors do not necessarily prescribe the most effective treatments. In the United Kingdom, for example, more than a third of general practitioners prescribe norethisterone—arguably the least effective option—as first line treatment, whereas only 1 in 20 prescribe tranexamic acid—probably the most effective first line treatment.6 The problem is not confined to primary care. In New Zealand, where the use of tranexamic acid is restricted to secondary care, 50% of gynaecologists still use luteal phase progestogens, and less than 10% use tranexamic acid.7

Summary points

Menorrhagia is an important healthcare issue

Despite widely available evidence inappropriate treatments are being prescribed

Guidelines exist for the appropriate management of menorrhagia

Appropriate treatments enhance patient choice and may increase patient satisfaction

Medical treatments may provide an effective alternative to surgery

Methods

This review attempts to provide a rational overview of the diagnostic and therapeutic management of menorrhagia, relying on the systematic reviews presented in three papers—two guidelines for the management of excessive menstrual loss published in 19988,9 and a consensus view published in 199510—and the Cochrane library for the source literature.

Cause and pathology of menorrhagia

Menorrhagia can be associated with both ovulatory and anovulatory ovarian cycles. It is important to distinguish the menstrual consequences of each cycle. Ovulatory ovarian cycles give rise to regular menstrual cycles whereas anovulatory cycles result in irregular menstruation or, extremely, amenorrhoea. This distinction is critical in management. Both ovulatory and anovulatory cycles can give rise to excessive menstrual loss in the absence of any other abnormality; so called dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Other disorders may be associated with excessive loss, for example, fibroids and adenomyosis, but the association may not always be causal. Endocrine disorders do not cause excessive menstrual loss, with the exception of the endocrine consequences of anovulation. Equally, except in selected populations, haemostatic disorders are rare causes of menorrhagia despite suggestions to the contrary.11

Excessive menstrual loss in regular menstrual cycles is the most common clinical presentation. Such patients ovulate regularly. Laboratory based research has shown that several abnormalities can occur in the endometrium of women with this problem—for example, increased fibrinolytic activity12 and increased production of prostaglandins.13 These observations provide the rational basis for treatment in these women.

One consequence of excessive menstrual loss is iron deficiency anaemia. In the western world menorrhagia is the commonest cause of iron deficiency anaemia, and low haemoglobin concentrations may predict objectively heavy menstrual loss.14

Investigations

Numerous investigations are undertaken for menorrhagia. The purpose of investigation is threefold: (a) to assess the morbidity associated with excessive menstrual loss, (b) to exclude major intrauterine disease, and (c) to assess the importance or otherwise of coexistent disorders. Box B2 details the utility of commonly performed investigations.

Box 2.

: Utility of commonly performed investigations for menorrhagia

- Full blood count

- Coagulation screen

- Tests for coagulopathies such as von Willebrand's disease should only be undertaken when specifically indicated by the history

- Thyroid function tests

- Other endocrine investigations

- Pelvic ultrasound

- Routine pelvic ultrasound has little place in evaluating the primary complaint of excessive menstrual loss.8 It is of value in evaluating other pelvic disorders discovered during clinical examination

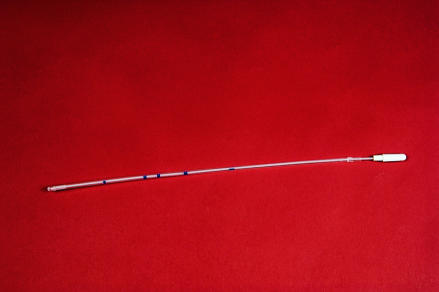

- Endometrial sampling

- As part of initial assessment there is no place for endometrial sampling (fig 1).9 Sampling should be combined with further assessment of the endometrial cavity, for example, hysteroscopy, in selected cases only. Selected cases would include women over 40, women complaining of intermenstrual bleeding, and after a failed trial of medical treatment

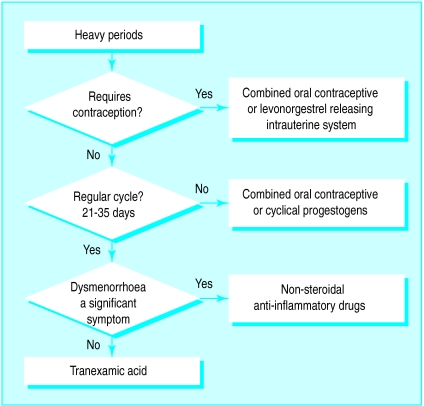

Choosing an appropriate treatment

In most clinical cases no specific abnormality will have been identified from the history, examination, and investigation; so called dysfunctional uterine bleeding. The choice of treatment must therefore be considered in relation to several factors (box B3). An element of choice for the patient is important. It has been suggested that involving patients in the decision making process may increase the effectiveness of treatment.19 There is, however, a need to properly inform patients to empower them to make informed choices.

Box 3.

: Factors influencing treatment choice

- Presence of ovulatory or anovulatory cycles

- Need for contraception

- Patient preference (particularly desire to avoid hormonal therapy)

- Contraindications to treatment

Medical treatment can be conveniently divided into non-hormonal and hormonal therapy. As there is no hormonal defect17,18 the use of hormonal therapy does not correct an underlying disorder but merely imposes an external control of the cycle. For many women, cycle control is as important an issue as the degree of menorrhagia.

The two main first line treatments for menorrhagia associated with ovulatory cycles are non-hormonal; the antifibrinolytic tranexamic acid and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The effectiveness of these treatments has been shown in randomised trials20–22 and reported in systematic reviews of treatment.8,9,23,24

Tranexamic acid reduces menstrual loss by about a half and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs reduced it by about a third. Both have the advantage of only being taken during menstruation itself—an aid to compliance—and are particularly useful in those women who either do not require contraception or do not wish to use a hormonal therapy (fig 2). They are also of value in treating excessive menstrual blood loss associated with the use of non-hormonal intrauterine contraceptive devices.

Figure 2.

Levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system may be an effective alternative to surgery and useful in patients requiring contraception

Traditionally, hormonal therapy for menorrhagia has been progestogens given during the luteal phase of the cycle. Such treatments are ineffective.25 Despite this they remain the first choice of many general practitioners and gynaecologists.6,7 Progestogens are effective when given for 21 days in each cycle,25,26 but the side effects may be such that patients would not choose to continue with treatment.26 Although progestogens have a contraceptive effect their use in this way may not be the best choice where contraception is required by the patient.

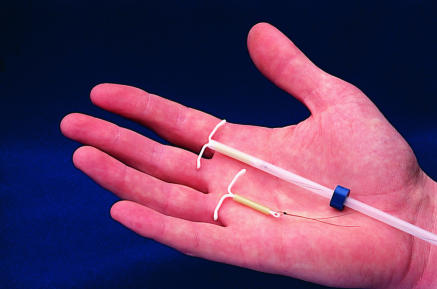

The combined contraceptive pill is both an effective contraceptive and treatment for menorrhagia when compared with other medical treatment.27 It is not, however, possible to expand upon this statement as there is a lack of good quality data,27 and the use of the contraceptive pill in this area has been insufficiently studied. Nevertheless, like cyclical progestogens, combined oral contraceptives are useful for anovulatory bleeding as they impose a cycle. More fully evaluated is the recently licensed levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system. This system (fig 3) consists of a T shaped intrauterine device sheathed with a reservoir of levonorgestrel that is released at the rate of 20 μg daily. This low level of hormone minimises the systemic progestogenic side effects and patients are more likely to continue with this therapy than cyclical progestogen therapy.26 The levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system, marketed as Mirena in the United Kingdom, is not yet licensed for use in the treatment of menorrhagia but when contraception is also required its use is legitimate. It exerts its clinical effect by preventing endometrial proliferation and consequently reduces both the duration of bleeding and the amount of menstrual loss.27 For up to 6 months patients may experience irregular bleeding or spotting, especially in the first 3 months, but by 12 months most women have only light bleeding, and a major proportion are amenorrhoeic.9 Many of the potential problems of bleeding and spotting can be overcome by thorough pretreatment counselling.

Figure 3.

Levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system (Mirena)

The levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system is advocated as an alternative to surgery. Two studies have examined the effect of offering this treatment to women on waiting lists for hysterectomy.28,29 In the first of these studies 50 women on a waiting list were offered this treatment, and 82% (41/50) were removed from the waiting list as a result.28 Lahteenmaki et al29 randomised women on surgical waiting lists to continue with their current regimen or to use a levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system; 64% of women using the system cancelled their surgery compared with 14% of women not using the system.27 When compared with minimally invasive techniques it seems to be equally effective.30 Whether this treatment will provide a long term alternative to surgery remains to be evaluated.

Excessive menstrual loss is a major healthcare problem. The publication of guidelines8,9 acknowledges that inappropriate management is being applied. Effective medical treatments exist (box B4) and have a rational basis for their use. Increased use of effective treatments will improve patient choice and provide an alternative to surgery.

Box 4.

: Effective treatments for menorrhagia

- Tranexamic acid

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- Combined oral contraceptives

- Cyclical (21 days) progestogens

- The levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system (Mirena)

Figure 1.

Endometrial sampler

Acknowledgments

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Vessey MP, Villard-Mackintosh L, McPherson K, Coulter A, Yeates D. The epidemiology of hysterectomy: findings in a large cohort study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:402–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb13758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coulter A, McPherson K, Vessey M. Do British women undergo too many or too few hysterectomies? Soc Sci Med. 1988;27:987–994. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90289-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paul C, Skegg D, Smeijers J, Spear G. Contraceptive practice in New Zealand. NZ Med J. 1988;101:809–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hallberg L, Hogdahl A, Nilsson L, Rybo G. Menstrual blood loss—a population study: variation at different ages and attempts to define normality. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1966;45:320–351. doi: 10.3109/00016346609158455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MORI. Women's health in 1990. Market Opinion and Research International; 1990. (Research study conducted on behalf of Parke-Davis Research Laboratories.) [Google Scholar]

- 6.United Kingdom and Ireland. Middlesex: IMS; 1994. Intercontinental Medical Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farquhar CM, Kimble R. How do NZ gynaecologists treat menorrhagia? Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;36:4. :1-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Advisory Committee on Health and Disability. Guidelines for the management of heavy menstrual bleeding. New Zealand: NACHD; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The initial management of menorrhagia. Evidence-based clinical guidelines, No1. London: RCOG; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 10.NHS Dissemination Centre. The management of menorrhagia. Effect Health Care Bull 1995;9.

- 11.Kadir RA, Economides DL, Sabin CA, Owens D, Lee CA. Frequency of inherited bleeding disorders in women with menorrhagia. Lancet. 1998;261:485–489. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08248-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dockery CJ, Sheppard B, Daly L, Bonnar J. The fibrinolytic enzyme system in normal menstruation and excessive uterine bleeding and the effect of tranexamic acid. Eur J Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Biol. 1987;24:309–318. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(87)90156-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith SK, Abel MH, Kelly RW, Baird DT. Prostaglandin synthesis in the endometrium of women with ovular dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1981;88:434–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1981.tb01009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janssen CA, Scholten PC, Heintz AP. A simple visual assessment technique to distinguish between menorrhagia and normal menstrual blood loss. Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;85:977–982. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00062-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott JC, Mussey E. Menstrual patterns of myxedema. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1964;90:161–165. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(64)90476-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krassas GE, Pontikides N, Kaltsas T, Papadopoulou P, Batrinos M. Menstrual disturbances in thyrotoxicosis. Clin Endocrinol. 1994;40:641–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1994.tb03016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haynes PJ, Anderson AB, Turnbull AC. Patterns of menstrual blood loss in menorrhagia. Res Clin Forums. 1979;1:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eldred JM, Thomas EJ. Pituitary and ovarian hormone levels in unexplained menorrhagia. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:775–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coulter A, Entwistle V, Gilbert D. Sharing decisions with patients: is the information good enough? BMJ. 1999;318:318–322. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7179.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Preston JT, Cameron IT, Adams EJ, Smith SK. Comparative study of tranexamic acid and norethisterone in the treatment of ovulatory menorrhagia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102:401–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb11293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersch B, Milsom I, Rybo G. An objective evaluation of flurbiprofen and tranexamic acid in the treatment of idiopathic menorrhagia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1988;67:645–648. doi: 10.3109/00016348809004279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonnar J, Sheppard BL. Treatment of menorrhagia during menstruation: randomised controlled trial of ethamsylate, mefenamic acid, and tranexamic acid. BMJ. 1996;313:579–582. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7057.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooke I, Lethaby A, Farquhar C Cochrane Collaboration, editors. Cochrane Library, Issue 1. Oxford: Update Software; 1999. Antifibrinolytics for heavy menstrual bleeding. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lethaby A, Augood C, Duckitt K Cochrane Collaboration, editors. Cochrane Library, Issue 1. Oxford: Update Software; 1999. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for heavy menstrual bleeding. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lethaby A, Irvine G, Cameron I Cochrane Collaboration, editors. Cochrane Library, Issue 1. Oxford: Update Software; 1999. Cyclical progestagens for heavy menstrual bleeding. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irvine GA, Campbell-Brown MB, Lumsden MA, Heikkila A, Walker JJ, Cameron IT. Randomised comparative trial of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system and norethisterone for the treatment of idiopathic menorrhagia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:592–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silverberg SG, Haukkamaa M, Arko H, Nilsson CG, Luukkainen T. Endometrial morphology during long-term use of levonorgestrel releasing intra-uterine devices. Int J Gynaecol Pathol. 1986;5:235–241. doi: 10.1097/00004347-198609000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barrington JW, Bowen-Simpkins P. The levonorgestrel intrauterine system in the management of menorrhagia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:614–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb11542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lahteenmaki P, Haukkamaa M, Puolakka J, Riikonen U, Sainio S, Suvisari J, et al. Open randomised study of use of levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system as an alternative to hysterectomy. BMJ. 1998;316:1122–1126. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7138.1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crosignani PG, Vercellini P, Mosconi P, Oldani S, Cortesi I, De Giorgi O. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device versus hysteroscopic endometrial resection in the treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:257–263. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]