A wide variety of complementary therapies claim to improve health by producing relaxation. Some use the relaxed state as a means of promoting psychological change. Others incorporate movement, stretches, and breathing exercises. Relaxation and “stress management” are found to a certain extent within conventional medicine. They are included here because they are generally not well taught in conventional medical curriculums and because of the overlap with other, more clearly complementary, therapies.

Techniques

Hypnosis

Hypnosis is the induction of a deeply relaxed state, with increased suggestibility and suspension of critical faculties. Once in this state, sometimes called a hypnotic trance, patients are given therapeutic suggestions to encourage changes in behaviour or relief of symptoms. For example, in a treatment to stop smoking a hypnosis practitioner might suggest that the patient will no longer find smoking pleasurable or necessary. Hypnosis for a patient with arthritis might include a suggestion that the pain can be turned down like the volume of a radio.

Definitions of terms relating to hypnosis

Hypnotic trance—A deeply relaxed state with increased suggestibility and suspension of critical faculties

Direct hypnotic suggestion—Suggestion made to a person in a hypnotic trance that alters behaviour or perception while the trance persists (for example, the suggestion that pain is not a problem for a woman under hypnosis during labour)

Post-hypnotic suggestion—Suggestion made to a person in a hypnotic trance that alters behaviour or perception after the trance ends (for example, the suggestion that in the future a patient will be able to relax at will and will no longer be troubled by panic attacks)

Some practitioners use hypnosis as an aid to psychotherapy. The rationale is that in the hypnotised state the conscious mind presents fewer barriers to effective psychotherapeutic exploration, leading to an increased likelihood of psychological insight.

Relaxation and meditation techniques

One well known example of a relaxation technique is known variously as sequential muscle relaxation (SMR), progressive relaxation, and Jacobson relaxation. The subject sits comfortably in a dark, quiet room. He or she then tenses a group of muscles, such as those in the right arm, holds the contraction for 15 seconds, and then releases it while breathing out. After a short rest, this sequence is repeated with another set of muscles. Gradually, different sets of muscle are combined.

The Mitchell method involves adopting body positions that are opposite to those associated with anxiety (fingers spread rather than hands clenched, for example). In autogenic training subjects concentrate on experiencing physical sensations, such as warmth and heaviness, in different parts of their bodies in a learnt sequence. Other methods encourage deepening and slowing the breath and a conscious attempt to let go of tension during exhalation.

Visualisation and imagery techniques are somewhat akin to hypnosis: the induction of a relaxed state followed by the use of suggestion. The main differences are that the suggestions are visual and usually generated by patients themselves. In cancer treatment, for example, patients may be asked to think of an image which represents their immune system killing off cancerous cells. One patient might imagine immune cells as sharks and the cancer cells as small fishes being eaten; another might think of a computer game in which the cancer cells are “zapped” by spaceships.

Meditation practice focuses on stilling or emptying the mind. Typically, meditators concentrate on their breath or a sound (“mantra”) which they repeat to themselves. They may, alternatively, attempt to reach a state of “detached observation,” in which they are aware of their environment but do not become involved in thinking about it. In meditation the body remains alert and in an upright poition.

Yoga practice involves postures, breathing exercises, and meditation aimed at improving mental and physical functioning. Some practitioners understand yoga in terms of traditional Indian medicine, with the postures improving the flow of “prana” energy around the body. Others see yoga in more conventional terms of muscle stretching and mental relaxation.

Tai chi is a gentle system of exercises originating from China. The best known example is the “solo form,” a series of slow and graceful movements that follow a set pattern. It is said to improve strength, balance, and mental calmness. Qigong (pronounced “chi kung”) is another traditional Chinese system of therapeutic exercises. Practitioners teach meditation, physical movements, and breathing exercises to improve the flow of Qi, the Chinese term for body energy.

What happens during a treatment?

Hypnosis

In hypnosis, patients normally see practitioners by themselves for a course of hourly or half hourly treatments. Some general practitioners and other medical specialists use hypnosis as part of their regular clinical work and follow a longer initial consultation with standard 10-15 minute appointments. Patients can be given a post-hypnotic suggestion that enables them to induce self hypnosis after the treatment course is completed. Some practitioners undertake group hypnosis, treating up to a dozen patients at a time—for example, teaching self hypnosis to antenatal groups as preparation for labour.

Relaxation and meditation techniques

Most relaxation techniques need to be practised daily. Typically, patients learn a relaxation technique over the course of eight weekly classes, each lasting an hour or so. Between classes, they practise by themselves for 15 to 30 minutes a day. After the course is over, patients are encouraged to continue on their own, though they may take further classes to learn advanced techniques or to maintain group support. Methods such as sequential muscle relaxation are learnt relatively readily: yoga, tai chi, and meditation can take years to master completely.

Most relaxation techniques are enjoyable, and many healthy individuals practise them without having particular health problems. Relaxation classes can also play a social function.

Unlike in many other complementary therapies, practitioners of relaxation techniques do not make diagnoses. They may use the conventional diagnoses as described by the patient to tailor the prescribed programme appropriately. However, in many cases the method of treatment does not depend on a precise diagnosis.

Therapeutic scope

The primary uses of hypnosis and relaxation techniques are in anxiety, in disorders with a strong psychological component (such as asthma and irritable bowel syndrome), and in conditions that can be modulated by levels of arousal (such as pain). They are also commonly used in programmes for stress management.

Research evidence

There is good evidence from randomised controlled trials that both hypnosis and relaxation techniques can reduce anxiety, particularly that related to stressful situations such as receiving chemotherapy. They are also effective for panic disorders and insomnia, particularly when integrated into a package of cognitive therapy (including, for example, sleep hygiene). A systematic review has found that hypnosis enhances the effects of cognitive behavioural therapy for conditions such as phobia, obesity, and anxiety.

Key studies of efficacy

Systematic reviews

Carroll D, Seers K. Relaxation for the relief of chronic pain: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs 1998;27:476-87

Eisenberg DM, Delbanco TL, Berkey CS, Kaptchuk TJ, Kupelnick B, Kuhl J, et al. Cognitive behavioral techniques for hypertension: are they effective? Ann Intern Med 1993;118:964-72

Kirsch I, Montgomery G, Sapirstein G. Hypnosis as an adjunct to cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995;63:214-20

Randomised controlled trials

Harvey RF, Hinton RA, Gunary RM, Barry RE. Individual and group hypnotherapy in treatment of refractory irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet 1989;i:424-5

Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR. Yoga for bronchial asthma: a controlled study. BMJ 1985;291:1077-9

Other

NIH Technology Assessment Panel on Integration of Behavioral and Relaxation Approaches into the Treatment of Chronic Pain and Insomnia. Integration of behavioral and relaxation approaches into the treatment of chronic pain and insomnia. JAMA 1996;276:313-8

Randomised controlled trials support the use of various relaxation techniques for treating both acute and chronic pain, although two recent systematic reviews suggest that methodological flaws may compromise the reliability of these findings. Randomised trials have shown hypnosis to be of value in asthma and in irritable bowel syndrome, yoga to be of benefit in asthma, and tai chi to help in reducing falls and fear of falls in elderly people. There is evidence from systematic reviews that hypnosis and relaxation techniques are probably not of general benefit in stopping smoking or substance misuse or in treating hypertension.

Relaxation and hypnosis are often used in cancer patients. There is strong evidence from randomised trials of the effectiveness of hypnosis and relaxation for cancer related anxiety, pain, nausea, and vomiting, particularly in children. Some practitioners also claim that relaxation techniques, particularly the use of imagery, can prolong life. There is currently insufficient evidence to support this claim.

Safety

Adverse events resulting from relaxation techniques seem to be extremely uncommon. Though rare, there have been reports of basilar or vertebral artery occlusion after yoga postures that put particular strain on the neck Sequential muscle relaxation should be avoided by people with poorly controlled cardiovascular disease as abdominal tensing can cause the Valsalva response. In patients with a history of psychosis or epilepsy there have been reports of further acute episodes after deep and prolonged meditation.

Hypnosis or deep relaxation can sometimes exacerbate psychological problems—for example, by retraumatising those with post-traumatic disorders or by inducing “false memories” in psychologically vulnerable individuals. Concerns have also been raised that it can bring on a latent psychosis, although the evidence is inconclusive. Hypnosis should be undertaken only by appropriately trained, experienced, and regulated practitioners. It should be avoided in established or borderline psychosis and personality disorders, and hypnotherapists should be competent at recognising and referring patients in these states.

Practice

Relaxation techniques are often integrated into other healthcare practices. For example, they may be included in programmes of cognitive behavioural therapy in pain clinics or occupational therapy in psychiatric units. Many different complementary therapists, such as osteopaths and massage therapists, may include some relaxation techniques in their work. Some nurses use relaxation techniques in the acute setting, such as in preparation for surgery. A small number of general practices offer regular classes in relaxation, yoga, or tai chi.

Regulation

The practice of many relaxation techniques is poorly regulated, and standards of practice and training are variable. This situation is unsatisfactory, but, given the relatively benign nature of many relaxation techniques, this variation in standards presents usually more of a problem of ensuring effective treatment and good professional conduct rather than one of avoiding adverse effects.

Other useful addresses

British Psychological Society (BPS)

St Andrews House, 48 Princess Road East, Leicester LE1 7DR Tel: 0116 254 9568. Fax: 0116 247 0787. URL: www.bps.org.uk

British Association of Counselling (BAC)

1 Regent Place, Rugby, Warwickshire CV21 2PJ. Tel: 01788 550899. Fax: 01788 562189. URL: www.counselling.co.uk

United Kingdom Council of Psychotherapy (UKCP)

167-9 Great Portland Street, London W1N 5FB. Tel: 0171 436 3002. Fax: 0171 436 3013. URL: www.ukcp.org.uk

British Complementary Medicine Association (BCMA)

249 Fosse Road South, Leicester LE3 1AE. Tel: 0116 282 5511

For hypnosis and deeper relaxation techniques, poor regulation is a more serious issue. The large number of hypnotherapy registers and the lack of a single regulating body makes selecting a practitioner difficult. Hypnotherapists with a conventional healthcare background (such as psychologists, doctors, dentists, and nurses) will be regulated by their conventional professional regulatory bodies. Some of the organisations registering hypnotherapists without a conventional background are member associations of the British Complementary Medicine Association (see third article of this series).

Further reading

Waxman D. Medical-dental hypnosis. London: Balliere Tindall, 1988

Karle H, Boys J. Hypnotherapy: a practical handbook. London: Free Association Books, reprinted 1996

Siegel B. Love, medicine and miracles. London: Arrow, 1989

When hypnosis is used as a psychotherapeutic or psychoanalytic tool practitioners require appropriate training and experience in clinical psychology, counselling, or psychotherapy. Hypnotherapists who practise in this way should be members of the British Psychological Society, the British Association of Counselling, or the United Kingdom Council of Psychotherapy.

Training

The British Society of Medical and Dental Hypnosis runs basic, intermediate, and advanced courses for doctors and dentists and holds regular scientific meetings. There is no standard training in hypnosis for practitioners without a conventional healthcare background.

Training in teaching relaxation techniques is provided through various routes from self teaching, through apprenticeships, to a number of short courses. Many yoga centres run courses to train yoga teachers. The Yoga Biomedical Trust also trains yoga therapists, who see patients individually and work on specific health problems.

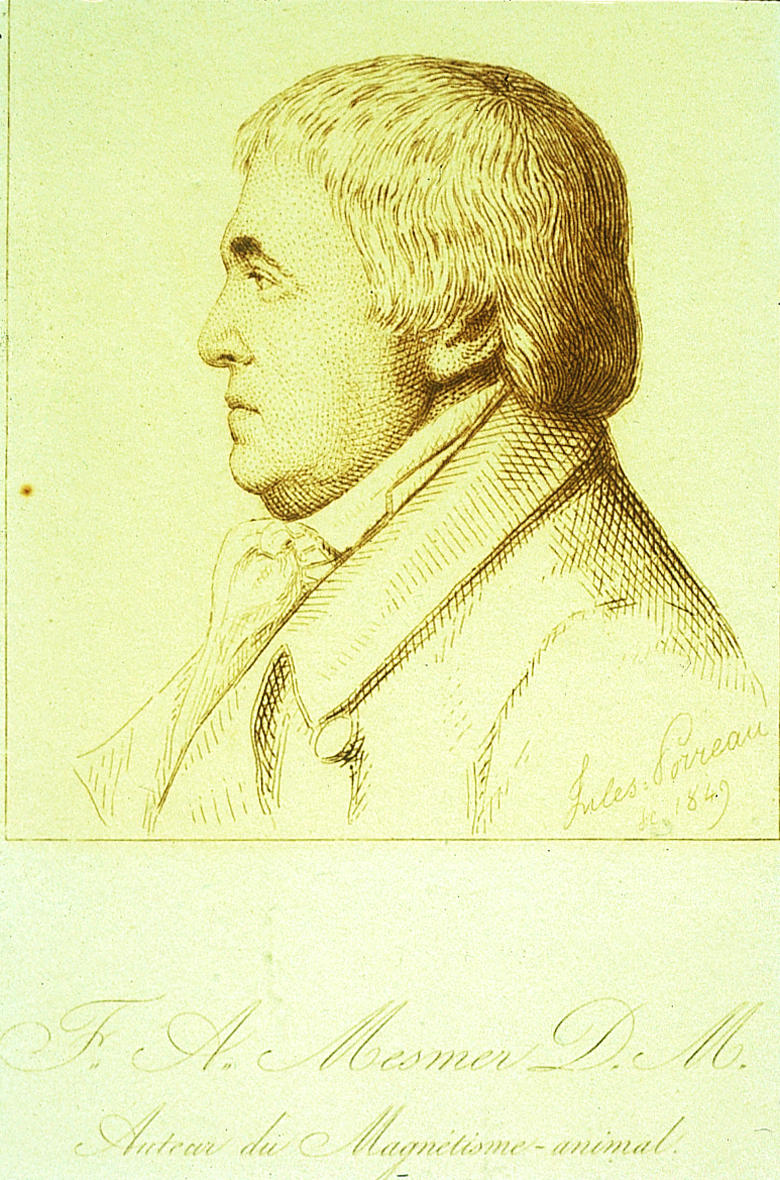

Figure.

Franz Mesmer, 1734-1815, was responsible for the rise in popularity, and notoriety, of hypnosis (“mesmerism”) in the 18th century

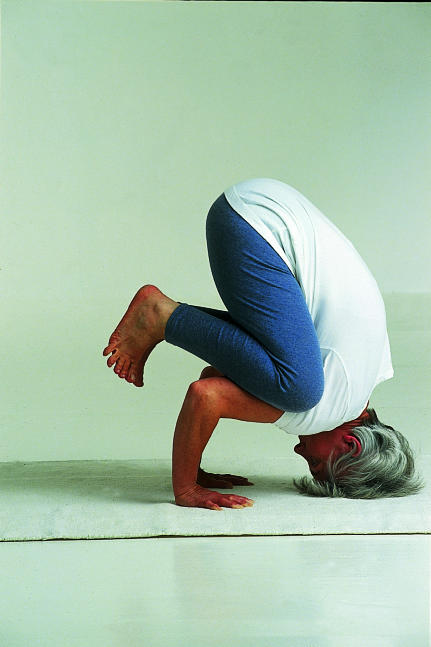

Figure.

Many relaxation techniques aim to increase awareness of areas of chronic unconscious muscle tension. They often involve a conscious attempt to release and relax during exhalation

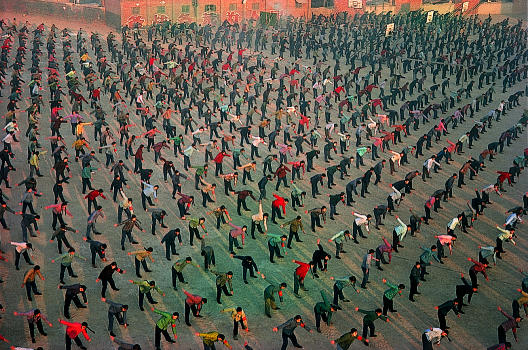

Figure.

In China many people practise tai chi for health promotion on a daily basis

Figure.

Self hypnosis can be taught to pregnant women as preparation for labour

Figure.

Relaxation classes can play a social function in addition to having therapeutic benefits

Figure.

Though rare, cases of basilar or vertebral artery occlusion have been reported after certain yoga positions that put stress on the neck

Acknowledgments

The picture of Mesmer is reproduced with permission of UT Medical Branch Library. The pictures of relaxation techniques are reproduced with permission of BMJ/Ulrike Preuss. The picture of tai chi exercise is reproduced with permission of Hutchison Library/Felix Greene. The picture of a pregnant woman is reproduced with permission of Mother and Baby Picture Library. The picture of yoga is reproduced with permission of Collections/Sandra Lousada.

Footnotes

The ABC of complementary medicine is edited and written by Catherine Zollman and Andrew Vickers. Catherine Zollman is a general practitioner in Bristol, and Andrew Vickers will shortly take up a post at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York. At the time of writing, both worked for the Research Council for Complementary Medicine, London. The series will be published as a book in Spring 2000.